Abstract

Prostate cancer is a common malignancy with various treatments from surveillance, surgery, radiation and chemotherapy. The institution of appropriate, effective treatment relies in part on accurate imaging. Molecular imaging techniques offer an opportunity for increased timely detection of prostate cancer, its recurrence, as well as metastatic disease. Advancements within the field of molecular imaging have been complex with some agents targeting receptors and others acting as metabolic intermediaries. In this article, we provide an overview of the most clinically relevant radiotracers to date based on a combination of the five states model and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines.

Prostate cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in the Western hemisphere.1 Treatment strategy varies from surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and palliative care and depends on timely and accurate disease detection. A current clinical states model in prostate cancer includes five progressive states: initial prostate evaluation prior to diagnosis, clinically localized disease, rising prostate-specific antigen (PSA) after treatment, non-castrate recurrent disease and castrate recurrent disease.2 The diagnostic strategy in prostate cancer depends on disease status. In early states, the focus is on assessing disease extent and prognostication, while late states emphasize determining biological profile and assessment of response to systemic treatment. Molecular imaging techniques are playing an increasing role in early prostate cancer detection and staging. Molecular imaging agents in prostate cancer can be divided into agents (antibodies, antibody fragments or small molecules) targeting receptors such as the androgen receptor (AR) or prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) and metabolic agents (small molecules) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Molecular imaging agents in prostate cancer

| Name | Localization mechanism |

| Receptor-targeting agents | |

| 18F-FDHT | Androgen receptor |

| ProstaScint | Antibody-based PSMA tracer |

| huJ591 antibody | Antibody-based PSMA tracer |

| 68Ga PSMA | Prostate-specific membrane antigen |

| 68Ga-HBED-CC 68Ga-DCFBC | Low molecular weight PSMA tracer |

| 18F-FDCPyL 18F-HBED-CC | PSMA inhibitor |

| Metabolic agents | |

| 18F-FDG | Glucose analogue/glycolysis |

| 11C/18F choline | Cell membrane synthesis |

| 11C-acetate | Cell membrane synthesis |

| 18F-fluciclovine | Amino acid analogue |

18F-FDG, Fluorine18- fluorodeoxyglucose; 18F-FDHT, fluoro-5a-dihydrotestosterone; 68Ga, gallium 68 , PSMA, prostate-specific membrane antigen; 68Ga-HBED-CC, Gallium-68(Ga-68)-labeled Glu-NH-CO-NH-Lys-(Ahx); 68Ga-DCFBC, N-[N-[(S)-1,3 dicarboxypropyl]carbamoyl]-4-(18)F-fluorobenzyl-L-cysteine; 18F-FDCPyL (2-(3-{1-carboxy-5-[(6-[18F]fluoro-pyridine-3-carbonyl)-amino]-pentyl}-ureido)-pentanedioic acid); 11C, carbon 11

Currently, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) drives oncologic decision-making in the USA. Our article is based on the most recent NCCN guidelines pertaining to prostate cancer, dated 21 February 2017.3 NCCN guidelines have a dedicated chapter on imaging, PROS-B. We have divided our discussion into three sections: (1) initial prostate cancer diagnosis, staging and risk stratification, focussed on locoregional staging by imaging (NCCN PROS-1 to PROS-6); (2) biochemical failure after locoregional therapy with curative intent (NCCN PROS 7–9); and (3) metastatic disease (NCCN PROS 9–14). At the beginning of each section, we will present current NCCN recommendations and then, we will attempt to forecast how molecular imaging will shape the future of prostate cancer management. It is worth noting that the selection of agents will likely be driven not only by clinical efficacy data, but also by regulatory and business environments, which may differ among countries.

Initial diagnosis, staging and risk stratification

The NCCN published a separate guideline for Prostate Cancer Early Detection (v. 1.2017, 5 June, 2017 is cited in this text). Baseline evaluation includes review of family and personal history, baseline digital rectal examination (DRE) and PSA measurements (PROSD-2), which is indicated in males >45 years of age. Transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy is considered in males aged 45–75 years and PSA >3 or males >75 years and PSA >4. Emerging data suggests that biopsy targeting using multiparametric MRI (mpMRI) and Transrectal ultrasound fusion may increase detection of clinically significant higher-risk cancers (Gleason Grade ≥4 + 3 = 7) and decrease detection of lower–risk cancers (Gleason sum 6 or lower volume Gleason 3 + 4).4,5

Initial staging approach is selected based on DRE, PSA, biopsy findings and life expectancy (PROS-1). Pelvic MRI (if not already performed) or CT are indicated if there is a T3–T4 primary or a T1–T2 primary with a nomogram that indicates a probability of lymph node involvement >10%. Nomograms are prognostic models that predict primary tumour spread and nodal involvement based on PSA, DRE and biopsy data.6 The goal of CT or MRI is to detect extensive nodal involvement, particularly fixation to the pelvic wall, which may alter management. Technetium-99m (Tc99m) methylene diphosphonate bone scan is not very sensitive, however, its low cost and wide availability make it essential in staging certain patients per appropriate use criteria (T1 primary and PSA >20, T2 primary and PSA >10, Gleason score ≥8, T3 and T4 primary or symptoms concerning for osseous metastatic disease).7Aside from bone scan, molecular imaging agents are not included in initial staging per NCCN guidelines, however this may change as new data emerges.

Following initial staging, patients are risk stratified into very low, low, intermediate, high and very high-risk (PROS-2 to PROS-6). Based on risk and life expectancy, management is selected, which may include observation, active surveillance, external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) or brachytherapy, sometimes combined with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), radical prostatectomy (RP) ± pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND) and ADT.

Molecular imaging of locoregional disease

Molecular imaging may play an important role in improving staging of high-risk or very high-risk disease (Gleason sum 8–10, T3-4, or PSA level >20 ng ml−1). If these patients are candidates for definitive treatment, multimodal therapy is generally used to improve the chance of cure, EBRT + ADT, EBRT + brachytherapy ± ADT or RP + pelvic lymph node dissection. This is very different than in lower-risk patients, in which single modality treatment is generally preferred to minimize side effects. In the NCCN algorithms, high-risk and very high-risk patients do not have regional nodal (N1) or metastatic (M1) disease proven by imaging or tissue sampling. If N1 disease is detected, the management is shifted from RP to radiation regimens. Thus, detecting advanced locoregional disease by imaging, affects both treatment selection and planning (the extent of radiation and brachytherapy fields, as well as nodal resection). If M1 (noncurable) disease is detected, definitive treatment is usually abandoned in favour of ADT to reduce morbidity.

Routine 18F-fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/CT (18F-FDG PET/CT) has a limited diagnostic role, especially in early, low volume disease. 18F-FDG suffers from limited sensitivity due to low glycolytic activity of prostate cancer and radiotracer activity within the urinary bladder that limits detection, as well as decreased specificity due to accumulation in infectious/inflammatory states. A recent article suggested a sequence of metabolic rearrangements in the progression of prostate cancer, with changes in intermediary metabolism preceding changes in glycolysis.8

Intermediary metabolism tracers, Carbon11 (11C)- or 18F-choline and 11C-acetate are involved in cell membrane synthesis. Choline is used to synthesize phosphatidylcholine, a cell membrane component, while acetate is used in fatty acid synthesis. Studies have been mixed in terms of sensitivity and specificity of choline-based PET tracers in detecting localized prostate cancer. Small tumour size, growth type and inability to distinguish infectious/inflammatory states from malignancy are some of the confounding factors.9,10 For example, several studies have found limited sensitivity of choline imaging in identifying extracapsular spread or seminal vesicle invasion when compared with MR.11,12 A review by De Bari et al13 concluded that mpMRI is superior to 11C or 18F-choline PET/CT in terms of sensitivity and specificity for localized prostate cancer.

Anti-3-amino-3-18F-fluorocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid (18F-FACBC or 18F- fluciclovine) is a radiolabelled cyclic amino acid (leucine analogue) with low renal clearance. Although, the US Federal Drug Administration (FDA) approved the agent in May 2016 for detection of biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer, it may be useful in initial staging of high-risk prostate cancer (Figure 1). Bogsrud et al14 performed 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT scans on 86 patients with histologically confirmed prostate cancer. Sensitivity for detecting the primary prostate lesion was 91.8% when compared to histopathology.Similarly, 21 patients were scanned using 18F-FACBC and mpMRI. 18F-FACBC sensitivity and specificity were 67 and 66%, respectively. With the addition of mpMRI, the positive predictive value increased from 50 to 73%.15

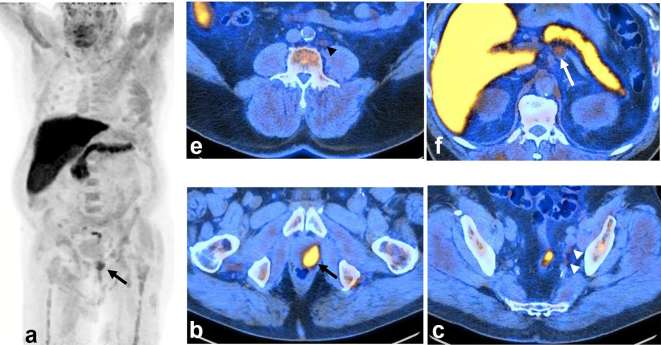

Figure 1.

A 73-year-old-male with T4N1M1a, newly diagnosed prostate adenocarcinoma, Gleason 4 + 4, PSA 8.3. 18F-FACBC PET/CT scan was ordered for staging purposes because of very high-risk of local disease on clinical assessment and mpMRI (which is not an FDA-approved indication). The scan showed intensely avid local disease in the left prostate (long black arrow) on MIP image (a) and axial PET/CT-fused image (b), mildly avid (uptake above blood pool and below bone marrow reference) in left internal iliac regional pelvic N1 subcentimetre lymph nodes (white arrow head), (c) mildly avid subcentimetre M1a metastatic left lower retroperitoneal lymph nodes (black arrow head), (d) and moderately avid (uptake above blood pool and below liver) mildly enlarged 1.6 cm short axis M1a left periceliac high (above renal veins) retroperitoneal lymph node (long white arrow), (e) Per 18F-FACBC interpretation criteria, the lymph nodes followed the expected spread pattern for prostate cancer and had uptake above blood pool (nodes <1 cm) or bone marrow (node >1 cm). Mildly avid bilateral inguinal nodes, not typical for spread of prostate cancer, are deemed negative (not shown). There is physiological activity in the head and neck mucosa, liver, pancreas, spleen, bowel and muscle (intense liver and pancreas activity is characteristic for 18F-FACBC scan). From treatment standpoint, left pelvic and lower retroperitoneal lymph nodes may be treated with extended PLND or extended-field EBRT. However, left periceliac lymph nodes would require systemic treatment with ADT. Thus, the scan provided essential information for patient management. 18F-FACBCPET, 18F-fluorocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid positron emission tomography; ADT, androgen deprivation therapy; EBRT, external beam radiation therapy; FDA, Federal Drug Administration; MIP, maximal intensity projection; mpMRI, multiparametric MRI; PLND, pelvic lymph node dissection.

Newer PSMA-based ligands, such as PSMA inhibitors are increasingly studied and may play a role in the characterization of localized disease. PSMA is a transmembrane glycoprotein overexpressed in prostate cancer cells. Its function is not clear, although its expression correlates with tumour grade, metastatic disease and neovasculature. Furthermore, the level of PSMA expression is more specific and not increased in infection/inflammation.16,17 A second generation, 18F-radiolabelled PSMA inhibitor, 2-(3-(1-carboxy-5-[(6-[18F]fluoro-pyridine-3-carbonyl)-amino]-pentyl)-ureido)-pentanedioic acid (18F-DCFPyL) was studied in 25 patients with high- or very high-risk disease. Imaging findings were compared to histopathological findings with sensitivity and specificity of 71.4 and 88.9%, respectively for N1 disease.18 In other studies, PSMA agents have been compared to standard cross-sectional imaging. Eiber et al19 studied 53 patients with biopsy proven prostate cancer and compared mpMRI, gallium-68 (Ga-68)-labelled Glu-NH-CO-NH-Lys-(Ahx) [(Ga 68)Ga-HBED-CC] PET and 68Ga-HBED-CC PET/MRI. PET/MRI improved diagnostic accuracy for prostate cancer localization with increased sensitivity of primary lesion detection 98.1, vs 92.5% for PET and 66% for mpMRI.A study by Maurer et al20 compared 68Ga-PSMA PET to CT/MRI in 130 patients, using histopathological correlation. Patient-based sensitivity of PSMA was 65.9% compared to 43.9% for anatomic imaging, specificity was 98.9% compared to 85.4%.PSMA-based ligands may have the potential to replace standard imaging techniques in higher-risk patients for preoperative lymph node staging.

Molecular imaging in detection of insignificant prostate cancer

The NCCN remains concerned about overdiagnosis and overtreatment of prostate cancer. In some patients with lower-risk (potentially non-lethal) cancer, the risk of treatment-related morbidity may be greater than the benefit of eliminating the cancer, therefore active surveillance is recommended. MRI over the past decade has evolved to improve prediction of insignificant prostate cancer over nomograms. T2 weighted and spectroscopic imaging detecting choline and citrate has progressed to a standardized imaging protocol called mpMRI with DWI (diffusion-weighted) and dynamic contrast enhanced-MR sequences. Increasingly, the use of mpMRI along with textural analysis has shown to correlate with Gleason scores and to improve classification of high- vs low-risk cancers.21–26 Additionally, Rozenberg et al27 found that whole lesion mean ADC, ADC ratio and ADC histogram analyses do not predict Gleason score upgrading. Accuracy did improve, however with the use of logistic regression models using textural features. A standardized reporting structure (PI-RADS and subsequently PI-RADS v2) was developed in conjunction.28,29 PI-RADS and PI-RADS v2, however, are ultimately dependent on the interpreting radiologist and so open to inter-reader variability. Wang et al30 found, however, that machine learning using MR radiomics can improve the diagnostic performance of PI-RADS v2.There is a hope that similar imaging breakthroughs in the evaluation of prostate cancer significance can be achieved with molecular imaging agents, particularly with newer-PSMA ligands. Currently, a large-scale multinational trial is underway with such an agent, MIP-1404 (Progenics) and SPECT/CT. As previously discussed, early data suggests that a combination of molecular imaging and MRI is superior to either modality alone in the assessment of local prostate cancer. With the advent of PET/MRI and SPECT/MRI hybrid scanners, it is conceivable that patients on active surveillance will be preferably evaluated with these modalities in the future.

Molecular imaging in radiation treatment planning

Accurate initial staging of locoregional disease optimizes treatment planning and has been investigated in the context of initial staging and biochemical recurrence.

In a study by López et al,31 37.5% (6/16) of high-risk patients had a change in the radiation treatment plan based on 11C-choline PET/CT findings. Side effects were fewer without sacrificing clinical and biochemical control. Garcia et al32 used the findings on 11C-choline PET/CT to escalate radiation dose in 11 of 61 patients with intermediate to high-risk prostate cancer and nodal metastases.

In the setting of biochemical recurrence, 70 patients with PSA equal to ≥0.05 and <1.0 ng ml−1 underwent 68Ga-PSMA PET/CT. A 29% high management impact was found, resulting in management changes related to RT fields and addition of systemic therapy due to disseminated disease.33

MR radiomics have also been studied in directing radiation treatment planning. Shiradkar et al34 e.g. found that using MRI features can target lesions while minimizing radiation to the rectum and bladder.

BIOCHEMICAL FAILURE AFTER LOCOREGIONAL THERAPY WITH CURATIVE INTENT

In prostate cancer, as opposed to most other solid cancers, response to initial definitive therapy is not assessed by imaging. with the exception of N1 or M1 disease treated with ADT in which patients are followed up with bone scans, no end-treatment imaging is recommended by the NCCN (PROS-7, 11, 12). For example, adjuvant radiation after RP is administered based on pathologic parameters.

Biochemical failure is observed in about 30% of patients after definitive treatment.35 Biochemical failure after RP is defined as PSA persistence or PSA recurrence (undetectable PSA after RP with a subsequent detectable PSA that increases on two or more determinations) (PROS-8). Post-radiation therapy recurrence is defined as PSA increase ≥2 ng ml−1 above nadir PSA or positive DRE (PROS-9).36 In the setting of post-RP biochemical failure, optional imaging includes chest X-ray, bone scan, abdominal and pelvic CT and 11C-choline PET/CT (PROS-8). If studies are negative for metastatic disease, salvage EBRT (targeting prostate bed and pelvic nodes) ± ADT may be used. The patients with metastatic disease may receive ADT or other systemic therapy. In the setting of radiation therapy recurrence, it is first determined if the patients are candidates for local salvage therapy (PROS-9). Local salvage candidates receive chest X-ray, bone scan and mpMRI of the prostate with optional CT or MR coverage of the abdomen and 11C-choline PET/CT. Ultimately, salvage therapy is administered to patients with biopsy proven local recurrence, without distant disease. Salvage therapy has been shown to be effective, however proper patient selection is paramount. The treatment will fail in patients with metastatic disease outside the pelvis or patients with regional nodal pelvic disease if only prostate or prostate bed are treated. Molecular imaging has a tremendous potential to facilitate patient selection.

Several meta-analyses of choline PET and PET/CT in the setting of castration-resistant prostate cancer with biochemical failure have yielded similar results. For example, Evangelista et al and Umbehr et al37,38 demonstrated a sensitivity and specificity around 85 and 92%, respectively in detecting local recurrence, lymph node or bone involvement in 19 studies from 2000 to 2012. In particular, meta-analyses of 18F-choline and 11C-choline have been performed showing no significant difference in performance between the radiolabels. An 18F-choline meta-analysis found a 91.8% sensitivity and 95.6% specificity in patients with biochemical recurrence, while a meta-analysis of 16 11C-choline studies demonstrated 89% sensitivity and 87% specificity.39 Another meta-analysis emphasized the importance of several variables affecting choline PET/CT detection rates. PSA levels and PSA kinetics were found to be important factors.40 Retrospective studies performed have also supported the importance of biochemical variables in detection rates. One such study by Cimitan et al41 confirmed the direct relationship between PSA levels and detection rates, but also found that 18F-choline detection rates (31 and 43%) were still considerable with PSA levels below 1 ng ml−1 or between 1 and 2 ng ml−1, respectively. In this study, Gleason score at initial diagnosis also affected detection rates, with a score higher than 7 associated with higher detection rates. Despite its effectiveness in prostate cancer biochemical failure and FDA approval in 2012, 11C-choline use remains limited in the USA due to isotope short half-life (20 min) requiring on-site cyclotron with a dedicated manufacturing process. A notable exception is the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN which spearheaded 11C-choline FDA approval and established a high-volume practice using this tracer.

Another metabolic radiotracer, 11C-acetate was also found to be most beneficial in the context of biochemical recurrence. Mena et al42 reported a sensitivity of 62% and specificity of 80%. Oyama et al43 found detection rates dependent on PSA levels, with sensitivities of 59% with PSA 43 ng ml−1 and 4% with 3 ng ml−1. In a retrospective study by Regula et al44 follow up in 120 patients with biochemical failure after prostatectomy and imaging with 11C-acetate PET/CT demonstrated 5-year overall survival of 100% in negative cases and only 80% in the originally positive cases. Although other tracers have higher sensitivities than 11C-acetate PET/CT, this agent may correlate with patient outcomes, aid in identifying different lesions, some of which may be indolent, and ultimately help predict the probability of progression of biochemical failure into symptomatic disease.

As previously discussed, 18F-fluciclovine (18F-FACBC) is currently FDA approved for biochemical failure in prostate cancer. Ren et al45 performed a meta-analysis of 18F-FACBC, evaluating six studies for a total of 251 patients and found an 87% pooled sensitivity and 66% pooled specificity (N = 251, six studies) for recurrent prostate cancer. In an International multicentre study of 18F-FACBC, 596 patients with biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer underwent PET/CT scans and were stratified based on PSA levels. 18F-FACBC demonstrated an ability to detect disease across a wide range of PSA levels. The subject level detection rate was 67.7%, decreasing to 42% at PSA levels <0.79 ng ml−1 and 86% at levels >6 ng ml−1.46 Some drawbacks of 18F-FACBC are due to high uptake in the liver, thereby decreasing sensitivity in hepatic metastases, physiological bone marrow activity and muscle uptake. A minority of patients will have some early renal and bladder activity.47 Schuster and colleagues proposed criteria for scan interpretation assigning different significance to lymph nodes based on the prostate cancer spread pattern (e.g. mild avidity in internal iliac or retroperitoneal nodes is considered malignant, while mild avidity in inguinal nodes is considered benign) and bone marrow and blood pool reference activities.48 In general, studies comparing different molecular agents in biochemical failure are rare. However, 18F-FACBC compared favourably against other metabolic agents. Nanni et al49 compared 18F-FACBC PET/CT in 100 patients with prostate cancer relapse to 11C-choline PET/CT. Patients were categorized by PSA level and in each group 18F-FACBC had more true-positive findings than with 11C-choline: PSA <1 ng ml−1, 1–2 ng ml−1, 2–3 ng ml−1 and ≥ 3 ng ml−1. 18F-FACBC is now commercially available in the USA under the trade name Axumin (Blue Earth Diagnostics, Ltd. Burlington, MA USA). Due to its wide availability, we anticipate that Axumin will be the most extensively utilized novel molecular imaging agent in prostate cancer in the near future.

Targeted molecular imaging using PSMA in biochemically recurrent prostate cancer has evolved greatly. Historically, PSMA was targeted with Indium-111 (111In) capromab pendetide murine IgG1 antibody (CYT-356, ProstaScint, Aytu BioScience, Inc. Englewood, CO USA) with tracer localization interpretation first aided by additional blood pool imaging and, subsequently by SPECT/CT. ProstaScint detected intracellular binding sites, only exposed in dead or dying cells, so its sensitivity to viable tumour sites and bone was decreased.50 In fact, reported sensitivities were as low as 10% for detecting extraprostatic disease.51 This was followed by huJ591, an antibody targeting the extracellular domain of PSMA, conjugated with 1, 4 ,7, 10-tetraazacyclododecane-1, 4, 7, 10-tetraacetic acid) and labelled with 111In for use in planar and SPECT imaging. It showed more accurate detection of tumour sites in soft tissue and bone.52–55

Ultimately, monoclonal antibodies have a long plasma half-life and poor soft tissue clearance, requiring the use of radionuclides with long half-lives and undesirable dosimetry.56 Small molecules (PSMA inhibitors) are now used as PSMA ligands to circumvent the problems with monoclonal antibodies. Low molecular weight PSMA targeting agents and PSMA inhibitors such as N-{N-[(S)−1,3 dicarboxypropyl] carbamoyl}−4-18F-fluorobenzyl-L-cysteine (18F-DCFBC) and 18F-DCFPyL offer faster tumour uptake and increased target to background ratios (Figure 2). Additionally, SPECT imaging is semi-quantitative and suffers from low spatial resolution therefore, 68Ga and 18F-labelled PET radiotracers are now more commonly used. In a retrospective analysis of 222 patients, 68Ga PSMA detection rates were noted at low PSA values, 96.8% at PSA level ≥2, 93% at 1–2, 72.7% at 0.5–<1, and 57.9% at 0.2–<0.5. While an association was seen with higher PSA velocities, no significant association was seen with PSA doubling time.57 In a study comparing 68Ga PSMA to 11C-choline, 68Ga-PSMA PET/CT SUVmax was higher in 79% of lesions, tumour to background ratio was over 10% higher in 95% of lesions and there was a higher detection rate by 68Ga-PSMA.58 A prospective trial of 17 patients with known progressive, metastatic prostate cancer found 592 positive lesions with 18F-DCFBC PET/CT vs 520 positive lesions with CT and bone scanning.59 This increased sensitivity was appreciated in nodal, osseous and visceral lesions with both hormone naïve and castration-resistant prostate cancers. In another study of 14 patients, Dietlein et al60 compared 68Ga-PSMA PET/CT with 18F-DCFPyL PET/CT and found the latter compared favourably, leading to investigating its role in staging, restaging and therapy planning. In a recent retrospective study of over 1000 patients, Afshar-Oromieh et al61 found that 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET/CT was positive (at least one lesion) in almost 80% of patients with biochemically recurrent prostate cancer. In addition, there was a correlation with PSA level and ADT. We anticipate that upon clearing hurdles of FDA approval and reimbursement, small molecule PET PSMA agents may become the preferred imaging technique for prostate cancer biochemical failure due to excellent target to background ratio and ease of interpretation.

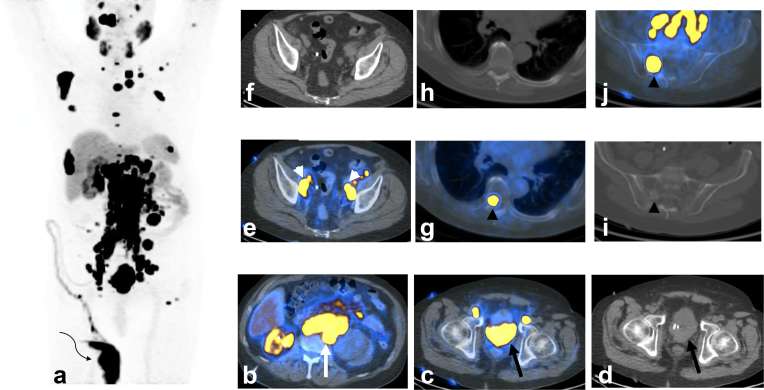

Figure 2. .

A 73-year-old-male with castrate resistant prostate cancer and extensive local, regional nodal and metastatic disease on novel PSMA agent PET/CT [clinical trial NCT02981368 “A PrOspective Phase 2/3 Multi-Center Study of 18F-DCFPyL PET/CT Imaging in Patients With PRostate Cancer: Examination of Diagnostic AccuracY (OSPREY)”, Progenics Pharmaceuticals, Inc]. The patient was diagnosed with prostate cancer about 20 years ago and treated with brachytherapy. About a decade ago, he experienced biochemical failure and CT showed extensive M1a retroperitoneal nodal disease. The cancer was initially hormone sensitive with PSA becoming undetectable. He eventually developed castrate resistant disease and failed chemotherapy and immunotherapy. MIP PET/CT image (a) shows extensive local, regional nodal and metastatic disease with only one functional right kidney with radiotracer excretion into nephrostomy bag (curved arrow). Axial PET/CT-fused image at the level of kidneys (b) shows functional right kidney, non-functioning severely hydronephrotic left kidney (due to obstruction by nodal disease, not shown), and extensive bilateral M1a retroperitoneal nodal involvement (long white arrow). Axial PET/CT-fused (c) and CT (d) images at the level of prostate show an extensive prostate lesion grossly invading the urinary bladder (long black arrow) and the absence of expected radiotracer in the bladder. Axial PET/CT-fused (e) and CT (f) images at the level of the upper pelvis show regional N1 nodal involvement (white arrow heads). Axial PET/CT-fused (g) and CT images (h) at the level of thoracic spine show a metastatic M1b osseous marrow lesion without CT correlate, which is presumably an early phase prior to adjacent bone response. Axial PET/CT-fused (i) and CT (j) images at the level of sacrum show a metastatic M1b osseous marrow lesion with a faintly sclerotic border indicating response of surrounding bone. Notable sites of physiological activity include the lacrimal glands, salivary glands, liver, spleen and bowel. Normal excretion pattern with intense renal activity and activity in the ureters and bladder is altered in this patient by disease and urinary diversion. MIP, maximal intensity projection; PET, positron emission tomography; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; PSMA, prostate-specific membrane antigen.

In summary, upon biochemical failure after curative intent treatment for prostate cancer, accurate restaging is of critical importance, since only the patients without distant metastatic disease may benefit from potentially morbid locoregional salvage therapies. In this regard, new molecular agents have the potential to exclude metastatic disease and facilitate salvage treatment planning via accurate localization of prostate cancer deposits in the pelvis.

METASTATIC DISEASE

In prostate cancer, metastatic disease most commonly occurs in non-regional (outside of pelvis) nodes and skeletal metastases. Organ involvement usually occurs late in the disease course and has a grave prognosis. From the management standpoint, it is important to establish the presence of metastatic disease, determine its location and extent and assess the response to treatment. For example, Radium-223 therapy is shown to extend survival in males with castration-recurrent prostate cancer with symptomatic osseous metastases and no visceral metastases or nodal disease >3–4 cm, which guides its utilization in treatment algorithms (PROS-D). Unlike initial staging and biochemical failure, the NCCN does not firmly stipulate imaging strategies in patients with established distant metastatic disease. In practice, a combination of bone scan and contrast-enhanced CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis is typically used.

Detection of metastatic disease

Bone scan remains the most utilized molecular imaging study for osseous metastatic disease. Bone-seeking radiotracers [e.g. Tc99m-labelled diphosphonates such as methylene diphosphonate for single-photon planar and SPECT/CT imaging and 18F-Sodium Fluoride (NaF) for dual-photon PET/CT] are markers of bone perfusion and turnover with the principal uptake mechanism being adsorption onto or into the crystalline structure of hydroxyapatite.62 Bone scan is indicated in selected higher-risk patients at initial staging (T1 and PSA >20, T2 and PSA >10, Gleason score ≥8, T3 and T4, or skeletal symptoms), biochemical failure and patients with established N1 and M1 disease. Despite a wide adoption of bone scan, the NCCN is aware of its shortcomings and a need for new better agents (PROS-B). In a series of 414 bone scans in 230 patients with post-RP biochemical failure, the rate of a positive bone scan for males with PSA <10 was only 4%, with positivity rising >50% for PSA >20.63 18F-NaF PET/CT is considered more sensitive and specific than single-photon bone scan. In a study by Even-Sapir et al64 NaF showed better sensitivity and specificity for prostate cancer metastatic disease, both at 100%, than routine single-photon bone scan. The sensitivity and specificity of routine bone scan was 82 and 57%.

Based on CT appearance, a majority of prostate cancer osseous metastases are sclerotic (80%), while the remainder are osteolytic or mixed, presumably due to a relatively slow growth rate and consequent ability of surrounding bone to confine the tumour. Bone-seeking radiotracers usually detect the sclerotic response to tumour rather than tumour itself. It is becoming evident that prostate cancer, like other non-bone forming metastases goes through a marrow phase in which they are avid on tumour-localizing agents, such as 18F-FACBC, but do not have CT or bone-seeking agent correlates. Conversely, metastases avid on bone-seeking imaging and sclerotic on CT, may not be avid with tumour-localizing agents. In this regard, Schuster and colleagues adjusted their 18F-FACBC interpretation criteria: (1) focal marrow 18F-FACBC uptake (above adjacent marrow background as a reference) clearly visible on maximum intensity projection images is suspicious for metastasis regardless of CT appearance; (2) dense sclerotic lesions may be metastases even if without 18F-FACBC uptake and should be further evaluated with MRI, 18F-NaF PET/CT or bone scan with SPECT/CT. Limited data are available comparing different imaging modalities for detection of osseous metastatic disease. In a prospective study on the accuracy of various imaging modalities for the detection of spine metastases, Poulsen et al65 reported that 18F-choline PET/CT had a higher specificity than bone scan and 18F-fluoride PET/CT (91 vs 82 and 54%) and that the sensitivity of 18F-choline PET/CT was higher than that of bone scan but lower than that of 18F-fluoride PET/CT (85 vs 51 and 93%). A study by Ceci et al66 found that 11C-choline detected lytic, blastic and marrow (no CT correlate) bone lesions.

In general, combined PET/CT with novel molecular agents is superior to CT alone in the detection of regional, non-regional and organ disease, as discussed in the prior section.

Treatment response

An important limitation of single- and dual-photon bone-seeking agents inherent to their localization mechanism is the inability to promptly and accurately detect treatment effect on tumour. Since bone scans and 18F-NaF PET/CT primarily detect a response of surrounding bone to prostate cancer, they frequently remain unchanged or even worsen (flare response) in the setting of effective tumour treatment, evidenced by decline in PSA and/or reduced uptake of tumour-localizing tracers. Similarly, a utilization of novel molecular imaging agents uncovered that many prostate cancer nodal and organ deposits are quite small, well beyond 1.5 cm short axis for nodes and 1 cm for other tumour thresholds for measurable lesions per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST). In fact, many involved nodes detected with molecular imaging agents have normal size and morphology on CT, a current workhorse for oncologic treatment response evaluation. Thus, the evaluation of changes in these small deposits with morphologic imaging is inherently limited, presenting an opportunity for molecular imaging. In addition to assessing tumour location and viability, molecular imaging agents can be designed to map specific tumour receptors aiding in the selection of therapeutic agents.

Agrawal et al 67 compared 68Ga-PSMA PET/CT to 18F-NaF PET/CT in 200 patients. NaF PET/CT is widely known for its high sensitivity in detecting bone metastases. In this study, 68Ga-PSMA detected most of the bone metastases seen on NaF studies. 68Ga-PSMA, however, did not remain positive in sclerotic bone lesions that continued to be positive on NaF studies. This observation raises the possibility of using PSMA agents in assessing tumour response to treatment.

Amanie et al68 followed 11 patients with intermediate-risk prostate cancer treated with EBRT for 12 months after treatment. 11C-choline PET/CT was performed at weeks 4 and 8 of radiation treatment; and 1, 2, 3, 6 and 12 months after radiation. Choline uptake within the prostate and PSA changes over several time points were similar. Lee et al69 evaluated tumour burden indices after various treatments for castration-resistant metastatic disease. After treatment, 42 patients completed 18F-fluorocholine PET/CT imaging, with tumour burden measurements metabolically active tumour volume and net total lesion activity. 30% or greater decline in net metabolically active tumour volume was considered a PET response and was seen in 20 patients. These patients experienced significantly longer times to PSA progression than non-responders (average 418 days vs 97 days for non-responders). 18F-fluorocholine may have a predictive value on different therapeutic agents.

18F-fluoro-5a-dihydrotestosterone (18F-FDHT) targets the AR that plays an important role in the growth and maintenance of the prostate gland. 18F-FDHT may be most useful as a marker of pharmacodynamic response. One study reported that enzalutamide- (AR receptor antagonist) induced 18F-FDHT uptake changes in metastatic lesions. 18F18-FDHT uptake may serve as a marker of adequate “targeting” of prostate cancer metastases with AR overexpression.70

Recent studies are also revealing the heterogeneity of prostate cancer, ultimately guiding treatment options. A study using 68Ga-PSMA-HBED-CC by Fendler et al 71 showed a sensitivity of 67% and specificity of 92% for lesion detection, however, not all tumours were positive for PSMA, suggesting heterogeneity among prostate cancers. Taking this into account, prostate cancer may be best evaluated with more than one imaging agent.

Moving forward, patient preparation, study acquisition, as well as interpretation and treatment response criteria will need to be standardized for new molecular imaging agents. For example, with 18F-FDG PET, a reduction of tumour uptake to blood pool or liver reference is considered complete response in tumour response systems [e.g. PET Response Criteria in Solid Tumours and Deauville scale for lymphoma] and is usually associated with better prognosis. Such references will need to be defined for new tracers, and in this regard, 18F-FACBC work by Schuster and colleagues is commendable. It will be interesting to see if treated sclerotic lesions without uptake on choline, FACBC or PSMA imaging confer better prognosis in prostate cancer, as they do with FDG in other cancers. The most optimal PET parameters will need to be selected and response criteria carefully designed and validated.

CONCLUSION

Molecular imaging is playing an ever-increasing role in prostate cancer diagnosis and staging, restaging and treatment response assessment, and ultimately management. Our current understanding of prostate cancer is also evolving by the study of these targeted molecular agents as we come to realize the heterogeneity of the disease. With all of this accumulating knowledge, we must also investigate clinical outcomes. This is fundamental to patients and can best be achieved with more prospective trials and multicentre collaborative efforts.

Contributor Information

Anne Marie Boustani, Email: annemarie.boustani@yale.edu.

Darko Pucar, Email: darko.pucar@yale.edu.

Lawrence Saperstein, Email: lawrence.saperstein@yale.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.DeSantis CE, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Siegel RL, Stein KD, Kramer JL, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 2014; 64: 252–71. doi: 10.3322/caac.21235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scher HI, Heller G. Clinical states in prostate cancer: toward a dynamic model of disease progression. Urology 2000; 55: 323–7. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(99)00471-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Prostate cancer guidelines; 2017. Available from: www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siddiqui MM, Rais-Bahrami S, Turkbey B, George AK, Rothwax J, Shakir N, et al. Comparison of MR/ultrasound fusion-guided biopsy with ultrasound-guided biopsy for the diagnosis of prostate cancer. JAMA 2015; 313: 390–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.17942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmed HU, El-Shater Bosaily A, Brown LC, Gabe R, Kaplan R, Parmar MK, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of multi-parametric MRI and TRUS biopsy in prostate cancer (PROMIS): a paired validating confirmatory study. The Lancet 2017; 389: 815–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32401-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ondracek RP, Kattan MW, Murekeyisoni C, Yu C, Kauffman EC, Marshall JR, et al. Validation of the kattan nomogram for prostate cancer recurrence after radical prostatectomy. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2016; 14: 1395–401. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donohoe KJ, Cohen EJ, Giammarile F, Grady E, Greenspan BS, Henkin RE, et al. Appropriate use criteria for bone scintigraphy in prostate and breast cancer: summary and excerpts. J Nucl Med 2017; 58: 14N–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shukla-Dave A, Wassberg C, Pucar D, Schöder H, Goldman DA, Mazaheri Y, et al. Multimodality imaging using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography in local prostate cancer. World J Radiol 2017; 9: 134–42. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v9.i3.134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farsad M, Schwarzenböck S, Krause BJ. PET/CT and choline: diagnosis and staging. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2012; 56: 343–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watanabe H, Kanematsu M, Kondo H, Kako N, Yamamoto N, Yamada T, et al. Preoperative detection of prostate cancer: a comparison with 11C-choline PET, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET and MR imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging 2010; 31: 1151–6. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martorana G, Schiavina R, Corti B, Farsad M, Salizzoni E, Brunocilla E, et al. 11C-choline positron emission tomography/computerized tomography for tumor localization of primary prostate cancer in comparison with 12-core biopsy. J Urol 2006; 176: 954–60. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pinaquy JB, De Clermont-Galleran H, Pasticier G, Rigou G, Alberti N, Hindie E, et al. Comparative effectiveness of [(18) F]-fluorocholine PET-CT and pelvic MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging for staging in patients with high-risk prostate cancer. Prostate 2015; 75: 323–31. doi: 10.1002/pros.22921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Bari B, Alongi F, Lestrade L, Giammarile F. Choline-PET in prostate cancer management: the point of view of the radiation oncologist. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2014; 91: 234–47. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2014.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bogsrud T, Willoch F, Kieboom J. Fluciclovine F18 PET-CT Scanning in patient with high risk primary prostate carcinoma. J Nucl Med 2016; 57(Suppl 2). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turkbey B, Mena E, Shih J, Pinto PA, Merino MJ, Lindenberg ML, et al. Localized prostate cancer detection with 18F FACBC PET/CT: comparison with MR imaging and histopathologic analysis. Radiology 2014; 270: 849–56. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13130240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Afshar-Oromieh A, Babich JW, Kratochwil C, Giesel FL, Eisenhut M, Kopka K, et al. The rise of PSMA ligands for diagnosis and therapy of prostate cancer. J Nucl Med 2016; 57(Suppl 3): 79S–89. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.170720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rowe SP, Drzezga A, Neumaier B, Dietlein M, Gorin MA, Zalutsky MR, et al. Prostate-specific membrane antigen-targeted radiohalogenated PET and therapeutic agents for prostate cancer. J Nucl Med 2016; 57(Suppl 3): 90S–6. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.170175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorin MA, Rowe SP, Patel HD. PSMA-targeted 18F-DCFPyl in the preoperative staging of men with high-risk prostate cancer: results of a prospective phase II single center study. J Urol 2017; 199: 126–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eiber M, Weirich G, Holzapfel K. 68Ga-PSMA HBED-CC PET/MRI in intermediate and high-risk prostate cancer improves the intraprostatic tumor localization compared to multiparametric MR. J Nucl Med 2016; 70: 829–36. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maurer T, Gschwend JE, Rauscher I, Souvatzoglou M, Haller B, Weirich G, et al. Diagnostic efficacy of (68)gallium-PSMA positron emission tomography compared to conventional imaging for lymph node staging of 130 consecutive patients with intermediate to high risk prostate cancer. J Urol 2016; 195: 1436–43. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.12.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fehr D, Veeraraghavan H, Wibmer A, Gondo T, Matsumoto K, Vargas HA, et al. Automatic classification of prostate cancer Gleason scores from multiparametric magnetic resonance images. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015; 112: E6265–E6273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505935112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nketiah G, Elschot M, Kim E, Teruel JR, Scheenen TW, Bathen TF, et al. T2-weighted MRI-derived textural features reflect prostate cancer aggressiveness: preliminary results. Eur Radiol 2017; 27: 3050–9. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4663-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sidhu HS, Benigno S, Ganeshan B, Dikaios N, Johnston EW, Allen C, et al. “Textural analysis of multiparametric MRI detects transition zone prostate cancer”. Eur Radiol 2017; 27: 2348–58. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4579-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wibmer A, Hricak H, Gondo T, Matsumoto K, Veeraraghavan H, Fehr D, et al. Haralick texture analysis of prostate MRI: utility for differentiating non-cancerous prostate from prostate cancer and differentiating prostate cancers with different Gleason scores. Eur Radiol 2015; 25: 2840–50. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-3701-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelcz F, Jarrard DF. Prostate cancer: the applicability of textural analysis of MRI for grading. Nat Rev Urol 2016; 13: 185–6. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2016.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vignati A, Mazzetti S, Giannini V, Russo F, Bollito E, Porpiglia F, et al. Texture features on T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging: new potential biomarkers for prostate cancer aggressiveness. Phys Med Biol 2015; 60: 2685–701. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/60/7/2685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rozenberg R, Thornhill RE, Flood TA, Hakim SW, Lim C, Schieda N. Whole-tumor quantitative apparent diffusion coefficient histogram and texture analysis to predict Gleason score upgrading in intermediate-risk 3 + 4 = 7 prostate cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2016; 206: 775–82. doi: 10.2214/AJR.15.15462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barentsz JO, Richenberg J, Clements R, Choyke P, Verma S, Villeirs G, et al. ESUR prostate MR guidelines 2012. Eur Radiol 2012; 22: 746–57. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2377-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weinreb JC, Barentsz JO, Choyke PL, Cornud F, Haider MA, Macura KJ, et al. PI-RADS prostate imaging - reporting and data system: 2015, version 2. Eur Urol 2016; 69: 16–40. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.08.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang J, Wu CJ, Bao ML, Zhang J, Wang XN, Zhang YD. Machine learning-based analysis of MR radiomics can help to improve the diagnostic performance of PI-RADS v2 in clinically relevant prostate cancer. Eur Radiol 2017; 27: 4082–90. doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-4800-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.López E, Lazo A, Gutiérrez A, Arregui G, Núñez I, Sacchetti A. Influence of (11)C-choline PET/CT on radiotherapy planning in prostate cancer. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother 2015; 20: 104–12. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2014.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia JR, Jorcano S, Soler M, Linero D, Moragas M, Riera E, et al. 11C-Choline PET/CT in the primary diagnosis of prostate cancer: impact on treatment planning. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2015; 59: 342–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Leeuwen PJ, Stricker P, Hruby G, Kneebone A, Ting F, Thompson B, et al. (68) Ga-PSMA has a high detection rate of prostate cancer recurrence outside the prostatic fossa in patients being considered for salvage radiation treatment. BJU Int 2016; 117: 732–9. doi: 10.1111/bju.13397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shiradkar R, Podder TK, Algohary A, Viswanath S, Ellis RJ, Madabhushi A. Radiomics based targeted radiotherapy planning (Rad-TRaP): a computational framework for prostate cancer treatment planning with MRI. Radiat Oncol 2016; 11: 148. doi: 10.1186/s13014-016-0718-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roehl KA, Han M, Ramos CG, Antenor JA, Catalona WJ. Cancer progression and survival rates following anatomical radical retropubic prostatectomy in 3,478 consecutive patients: long-term results. J Urol 2004; 172: 910–4. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000134888.22332.bb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roach M, Hanks G, Thames H, Schellhammer P, Shipley WU, Sokol GH, et al. Defining biochemical failure following radiotherapy with or without hormonal therapy in men with clinically localized prostate cancer: recommendations of the RTOG-ASTRO phoenix consensus conference. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006; 65: 965–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Evangelista L, Zattoni F, Guttilla A, Saladini G, Zattoni F, Colletti PM, et al. Choline PET or PET/CT and biochemical relapse of prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nucl Med 2013; 38: 305–14. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3182867f3c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Umbehr MH, Müntener M, Hany T, Sulser T, Bachmann LM. The role of 11C-choline and 18F-fluorocholine positron emission tomography (PET) and PET/CT in prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol 2013; 64: 106–17. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fanti S, Minozzi S, Castellucci P, Balduzzi S, Herrmann K, Krause BJ, et al. PET/CT with (11)C-choline for evaluation of prostate cancer patients with biochemical recurrence: meta-analysis and critical review of available data. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2016; 43: 55–69. doi: 10.1007/s00259-015-3202-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Treglia G, Ceriani L, Sadeghi R, Giovacchini G, Giovanella L. Relationship between prostate-specific antigen kinetics and detection rate of radiolabelled choline PET/CT in restaging prostate cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Clin Chem Lab Med 2014; 52: 725–33. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2013-0675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cimitan M, Evangelista L, Hodolič M, Mariani G, Baseric T, Bodanza V, et al. Gleason score at diagnosis predicts the rate of detection of 18F-choline PET/CT performed when biochemical evidence indicates recurrence of prostate cancer: experience with 1,000 patients. J Nucl Med 2015; 56: 209–15. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.141887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mena E, Turkbey B, Mani H, Adler S, Valera VA, Bernardo M, et al. 11C-Acetate PET/CT in localized prostate cancer: a study with MRI and histopathologic correlation. J Nucl Med 2012; 53: 538–45. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.096032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oyama N, Miller TR, Dehdashti F, Siegel BA, Fischer KC, Michalski JM, et al. 11C-acetate PET imaging of prostate cancer: detection of recurrent disease at PSA relapse. J Nucl Med 2003; 44: 549–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Regula N, Hauggman M, Johnasson S, Sörensen J. 11C-acetate PET/CT accurately predicts prostate-cancer specific survival in patients with biochemical relapse after prostatectomy. J Nucl Med 2016; 57(Suppl 2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ren J, Yuan L, Wen G, Yang J. The value of anti-1-amino-3-18F-fluorocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid PET/CT in the diagnosis of recurrent prostate carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Acta Radiol 2016; 57: 487–93. doi: 10.1177/0284185115581541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bach-Gansmo T, Nanni C, Nieh PT, Zanoni L, Bogsrud TV, Sletten H, et al. Multisite experience of the safety, detection rate and diagnostic performance of fluciclovine (18F) positron emission tomography/computerized tomography imaging in the staging of biochemically recurrent prostate cancer. J Urol 2017; 197: 676–83. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.09.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schuster DM, Nanni C, Fanti S, Oka S, Okudaira H, Inoue Y, et al. Anti-1-amino-3-18F-fluorocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid: physiologic uptake patterns, incidental findings, and variants that may simulate disease. J Nucl Med 2014; 55: 1986–92. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.143628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Savir-Baruch B, Zanoni L, Schuster DM. Imaging of prostate cancer using fluciclovine. PET Clin 2017; 12: 145–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cpet.2016.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nanni C, Zanoni L, Pultrone C, Schiavina R, Brunocilla E, Lodi F, et al. (18)F-FACBC (anti1-amino-3-(18)F-fluorocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid) versus (11)C-choline PET/CT in prostate cancer relapse: results of a prospective trial. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2016; 43: 1601–10. doi: 10.1007/s00259-016-3329-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hinkle GH, Burgers JK, Neal CE, Texter JH, Kahn D, Williams RD, et al. Multicenter radioimmunoscintigraphic evaluation of patients with prostate carcinoma using indium-111 capromab pendetide. Cancer 1998; 83: 739–47. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Troyer JK, Beckett ML, Wright GL. Location of prostate-specific membrane antigen in the LNCaP prostate carcinoma cell line. Prostate 1997; 30: 232–42. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosenthal SA, Haseman MK, Polascik TJ. Utility of capromab pendetide (ProstaScint) imaging in the management of prostate cancer. Tech Urol 2001; 7: 27–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bander NH, Milowsky MI, Nanus DM, Kostakoglu L, Vallabhajosula S, Goldsmith SJ. Phase I trial of 177lutetium-labeled J591, a monoclonal antibody to prostate-specific membrane antigen, in patients with androgen-independent prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 4591–601. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tagawa ST, Akhtar NH, Christos PJ, Osborne J, Vallabhajosula S, Freedy S. Noninvasive measurement of prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA) expression with radiolabeled J591 imaging: a prognostic tool for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). J Clin Oncol 2013; 31(Suppl. 5): 11081. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Osborne JR, Green DA, Spratt DE, Lyashchenko S, Fareedy SB, Robinson BD, et al. A prospective pilot study of (89)Zr-J591/prostate specific membrane antigen positron emission tomography in men with localized prostate cancer undergoing radical prostatectomy. J Urol 2014; 191: 1439–45. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.10.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rowe SP, Gage KL, Faraj SF, Macura KJ, Cornish TC, Gonzalez-Roibon N, et al. ¹⁸F-DCFBC PET/CT for PSMA-based detection and characterization of primary prostate cancer. J Nucl Med 2015; 56: 1003–10. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.154336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eiber M, Maurer T, Souvatzoglou M, Beer AJ, Ruffani A, Haller B, et al. Evaluation of hybrid ⁶⁸Ga-PSMA ligand PET/CT in 248 patients with biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. J Nucl Med 2015; 56: 668–74. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.154153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Afshar-Oromieh A, Zechmann CM, Malcher A, Eder M, Eisenhut M, Linhart HG, et al. Comparison of PET imaging with a (68)Ga-labelled PSMA ligand and (18)F-choline-based PET/CT for the diagnosis of recurrent prostate cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2014; 41: 11–20. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2525-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rowe SP, Macura KJ, Ciarallo A, Mena E, Blackford A, Nadal R, et al. Comparison of prostate-specific membrane antigen–based 18F-DCFBC PET/CT to conventional imaging modalities for detection of hormone-naïve and castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer. J Nucl Med 2016; 57: 46–53. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.163782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dietlein M, Kobe C, Kuhnert G, Stockter S, Fischer T, Schomäcker K, et al. Comparison of [(18)F]DCFPyL and [ (68)Ga]Ga-PSMA-HBED-CC for PSMA-PET imaging in patients with relapsed prostate cancer. Mol Imaging Biol 2015; 17: 575–84. doi: 10.1007/s11307-015-0866-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Afshar-Oromieh A, Holland-Letz T, Giesel FL, Kratochwil C, Mier W, Haufe S, et al. Diagnostic performance of 68Ga-PSMA-11 (HBED-CC) PET/CT in patients with recurrent prostate cancer: evaluation in 1007 patients. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2017; 44: 1258–68. doi: 10.1007/s00259-017-3711-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wong KK, Piert M. Dynamic bone imaging with 99mTc-labeled diphosphonates and 18F-NaF: mechanisms and applications. J Nucl Med 2013; 54: 590–9. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.114298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dotan ZA, Bianco FJ, Rabbani F, Eastham JA, Fearn P, Scher HI, et al. Pattern of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) failure dictates the probability of a positive bone scan in patients with an increasing PSA after radical prostatectomy. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 1962–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Even-Sapir E, Metser U, Mishani E, Lievshitz G, Lerman H, Leibovitch I. The detection of bone metastases in patients with high-risk prostate cancer: 99mTc-MDP Planar bone scintigraphy, single- and multi-field-of-view SPECT, 18F-fluoride PET, and 18F-fluoride PET/CT. J Nucl Med 2006; 47: 287–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Poulsen MH, Petersen H, Høilund-Carlsen PF, Jakobsen JS, Gerke O, Karstoft J, et al. Spine metastases in prostate cancer: comparison of technetium-99m-MDP whole-body bone scintigraphy, [(18) F]choline positron emission tomography(PET)/computed tomography (CT) and [(18) F]NaF PET/CT. BJU Int 2014; 114: 818–23. doi: 10.1111/bju.12599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ceci F, Castellucci P, Graziani T, Schiavina R, Chondrogiannis S, Bonfiglioli R, et al. 11C-choline PET/CT identifies osteoblastic and osteolytic lesions in patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Clin Nucl Med 2015; 40: e265–e270. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000000783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Agrawal A, Natarajan A, Bakshi G, Prakash G, Mahantshetty U, Murthy V. Evaluation of skeletal metastases of prostate cancer with 68Ga PSMA PET/CT and 18F-NaF PET/CT and its comparison. J Nucl Med 2016; 57: s2–559. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Amanie J, Jans HS, Wuest M, Pervez N, Murtha A, Usmani N, et al. Analysis of intraprostatic therapeutic effects in prostate cancer patients using [(11)C]-choline pet/ct after external-beam radiation therapy. Curr Oncol 2013; 20: 104–10. doi: 10.3747/co.20.1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee J, Sato M, Coel M, Lee K-H, Kwee S. Whole-body tumor burden measurements on 18F-fluorocholine PET/CT may have a predictive value following specific treatments for castrate-resistant prostate cancer. J Nucl Med 2016; 57(Suppl 2): 463. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Scher HI, Beer TM, Higano CS, Anand A, Taplin ME, Efstathiou E, et al. Antitumour activity of MDV3100 in castration-resistant prostate cancer: a phase 1–2 study. Lancet 2010; 375: 1437–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60172-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fendler WP, Schmidt DF, Wenter V, Thierfelder KM, Zach C, Stief C, et al. 68Ga-PSMA PET/CT detects the location and extent of primary prostate cancer. J Nucl Med 2016; 57: 1720–5. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.172627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]