Abstract

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) defines the following types of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) as favorable-risk: acute promyelocytic leukemia with t(15;17) (APL); AML with corebinding factor (CBF) rearrangements, including t(8;21) and inv(16) or t(16;16) without mutations in KIT (CBF-KITwt); and AML with normal cytogenetics and mutations in NPM1 (NPM1mut); or biallelic mutations in CEBPA (CEBPAmut/mut), without FLT3-ITD. Although these AMLs are categorized as favorable risk by NCCN, clinical experience suggests that there are differences in clinical outcome amongst these cytogenetically and molecularly distinct leukemias. This study compared clinical and genotypic characteristics of 60 patients with favorable-risk AML, excluding APL, and demonstrated significant differences between them. Patients with NPM1mut AML were significantly older than those in the other groups. Targeted next-generation sequencing on DNA from peripheral blood or bone marrow revealed significantly more mutations in NPM1mut AML than the other favorable-risk diseases, especially in genes related to DNA splicing and methylation. CEBPAmut/mut AMLs exhibited more mutations in transcription-related genes. Patients with NPM1mut AML and CEBPAmut/mut AML show significantly reduced overall survival in comparison with CBF-KITwt AML. These findings emphasize that favorable-risk AML patients have divergent outcomes and that differences in clinical and genotypic characteristics should be considered in their evaluation and management.

Keywords: acute myeloid leukemia, favorable risk, core binding factor, molecular diagnostics

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a neoplasm defined by clonal expansion of abnormal myeloblasts, which replace normal hematopoiesis. Disease-related mortality is common, with 5-year survival less than 25% (1). While generally considered an aggressive disease, there is considerable heterogeneity in genetics, management, natural history, and outcome of AML (1–3). Over the past few decades common chromosomal abnormalities and gene mutations have been identified, forming the basis for sub-classification and risk stratification of AML (3).

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) classification for AML categorizes patients into favorable, intermediate, and poor risk groups based on cytogenetic and molecular abnormalities (4). In this system, favorable-risk AML includes those that carry the following abnormalities: t(15;17) [PML-RARA] (APL); core-binding factor (CBF) rearrangements, including t(8;21) [RUNX1-RUNX1T1] and inv(16) or t(16;16) [CBFB-MYH11], without mutations in KIT (CBF-KITwt AML); normal karyotype with mutations in NPM1 in the absence of FLT3 internal tandem duplication (ITD) (NPM1mut AML); and normal karyotype with biallelic mutations in CEBPA (CEBPAmut/mut AML). The European LeukemiaNet (ELN) uses a similar classification scheme, although the criteria for favorable risk differ in some respects from NCCN (5). Patients carrying these common genetic abnormalities clearly exhibit superior clinical outcomes compared with those with intermediate or poor-risk AML (6–9).

AML risk stratification not only informs prognosis, but also drives the therapeutic approach to patients with AML (4,5). For example, both NCCN and ELN guidelines recommend standard induction chemotherapy followed by high-dose cytarabine consolidation for patients in the favorable risk group (except APL), while intermediate- and poor-risk patients should be considered for hematopoietic stemcell transplant (HSCT), if possible, in first remission (4,5).

Despite recommended approaches to categorization and treatment of favorable-risk AML, there is evidence to suggest differences in patient characteristics, biology, and clinical behavior of the different genetic subtypes in this risk category (10,11). This study is a retrospective comparison of clinical characteristics, mutational profiles, and outcomes in patients with favorable-risk AML (excluding APL, which has a distinct pathophysiology and treatment based on its defining PML-RARA rearrangement). The differences observed between the favorable-risk subtypes alter the prognosis and may enable more informed decisions with regard to the appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic approach to these patients.

Materials and Methods

Patients

This study was approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board. Patients presenting untreated and at first diagnosis with AML were identified through institutional database searches. Data was collected using a REDCap database (12). Cytogenetic and molecular testing results were obtained from pathology and medical records. Patients were included if they met criteria for NCCN favorable risk (4) in one of the following categories: 1. CBF-KITwt AML – CBF rearrangements, including t(8;21) and inv(16) or t(16;16), without mutations in KIT; 2. NPM1mut AML – normal karyotype with mutations in NPM1 in the absence of FLT3 ITD; or 3. CEBPAmut/mut AML - normal karyotype with biallelic mutations in CEBPA. For this analysis, patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia with t(15;17) and patients presenting with relapsed AML or AML transformed from another myeloid neoplasm were specifically excluded.

Demographic data, clinical and laboratory findings at diagnosis, therapeutic course, and outcomes were determined by searching the medical record of each patient. Criteria for treatment response and survival followed the definitions of the International Working Group for Diagnosis, Standardization of Response Criteria, Treatment Outcomes, and Reporting Standards for Therapeutic Trials in Acute Myeloid Leukemia (13). Complete remission (CR) was defined as <5% bone marrow blasts in the setting of peripheral blood cell count recovery (neutrophils >1,000/µL; platelets >100,000/µL) after single chemotherapy induction, or after second induction if completed within 30 days of first induction. Overall survival (OS) was measured from the time of diagnosis and defined as absence of death from any cause. Relapse-free survival (RFS) was defined as absence of disease relapse or death from any non-AML cause measured from the time of CR. Thus, RFS included only patients that achieved CR after induction chemotherapy. Surviving patients were censored at the time of last clinic visit or laboratory test draw.

Treatment

For patients treated with standard therapy, induction chemotherapy consisted of 7 days of cytarabine with 3 days of either idarubicin or daunorubicin. For patients achieving CR, most received multiple cycles of cytarabine consolidation. For patients that did not achieve CR with initial induction, reinduction with one of various regimens (CLAG-M, MEC, clofarabine/cytarabine, or FLAG) was performed. A subset of patients (18/60; 30%) was treated on various clinical trials and a subset (13/60; 22%) went to allogeneic HSCT (see Table 1). Of these, 8/13 were transplanted in first remission (CR1), mostly NPM1mut patients (7/8), and 5/13 were transplanted in second remission (CR2), mostly CBF-KITwt patients (3/5).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients by Subcategory

| CBF | NPM1 | CEBPA | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 21a | 34 | 5 | |

| Age (yrs)b | 41 [20–74] | 65.5 [34–87] | 47 [30–71] | <0.0001 |

| Sex (M:F) | 11:10 | 17:17 | 4:1 | n.s. |

| % Blasts (marrow)c | 53.9±6.5 | 59.7±3.8 | 76.2±9.7 | n.s. |

| WBC (×103/µL)c | 68.3±19.2 | 44.2±10.4 | 43.7±31.0 | n.s. |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL)c | 9.2±0.5 | 9.4±0.3 | 10.0±1.7 | n.s. |

| Platelets (×103/µL)c | 59.4±8.8 | 74.8±9.0 | 38.8±9.5 | n.s. |

| LDH (U/L)c | 868±181 | 457±52 | 520±200 | n.s. |

| Initial Therapy | ||||

| Standard Induction | 21/21 (100%) | 27/34 (79%) | 5/5 (100%) | 0.048 |

| Hypomethylating agents | 0/21 (0%) | 4/34 (12%) | 0/5 (0%) | |

| None | 0/21 (0%) | 3/34 (9%) | 0/5 (0%) | |

| Clinical Triald | 4/21 (19%) | 12/34 (35%) | 2/5 (40%) | n.s. |

| Stem Cell Transplante | 4/21 (19%) | 8/34 (24%) | 1/5 (20%) | n.s. |

N = 12 for inv(16), N=9 for t(8;21);

Results expressed as median [range];

Results expressed as mean±SEM;

Clinical trial at any point during course of therapy;

N=8 transplanted in first remission; N=5 transplanted in second remission.

Mutation Profiling by Next-Generation Sequencing

Mutation profiling was performed by targeted next generation sequencing (NGS) on DNA extracted from pre-treatment bone marrow or peripheral blood samples. DNA isolated from each specimen was subjected to PCR-based, amplicon target enrichment using the TruSeq Amplicon Assay (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Coding and non-coding regions of 37 genes (ABL1, ASXL1, BCOR, BCORL1, BRAF, CALR, CBL, CDKN2A, CSF3R, DNMT3A, ETV6, EZH2, FBXW7, FLT3, GATA2, HRAS, IDH1, IDH2, JAK2, KIT, KRAS, MPL, MYD88, NPM1, NRAS, PHF6, PTEN, PTPN11, RUNX1, SETBP1, SF3B1, SRSF2, TET2, TP53, U2AF1, WT1, ZRSR2) were enriched and subsequently sequenced on a MiSeq instrument (Illumina, San Diego, CA) with paired-end, 186 base pair reads. Following mapping of the read data to the human genome (reference build GRCh37/hg19), single nucleotide variants, insertions and deletions with an allele frequency greater than 5% were detected utilizing a customized bioinformatic analytical pipeline.

Reported sequence variants were categorized as either known disease-associated mutations or variants of unknown significance (VUS). VUS identified in this analysis have unclear pathogenic potential, and thus were not included in the analysis. Functional mutation categories for mutations were those defined by Haferlach et al. (14).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism, version 5.02 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Quantitative variables were subjected to a D’Agostino and Pearson test to determine normality of distribution. Normally distributed variables were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Variables with non-normal distribution were compared using the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test. Survival curves were compared using the Mantel-Cox log-rank test.

Results

Sixty patients with NCCN favorable-risk AML (excluding APL) were studied. Demographic and clinical characteristics of these patients are noted in Table 1. There was a significant difference in age amongst the three groups, primarily due to increased age of NPM1mut AML patients (P<0.001). Presenting clinical features, including bone marrow blast percentage, white blood cell count, hemoglobin concentration, platelet count, and serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels, did not significantly differ between these groups. Similarly, there was no difference in the rate at which patients in different categories entered clinical trials or received HSCT.

Most patients, including all patients in the CBF-KITwt AML and CEBPAmut/mut AML categories, were treated initially with standard anthracycline and cytarabine-based induction chemotherapy (Table 1). Seven NPM1mut AML patients did not undergo induction: 4 were treated with hypomethylating agents only, and 3 received no therapy. In each case, this was primarily due to medical co-morbidities that precluded the safe administration of induction chemotherapy. These complications were likely associated with advanced age as these 7 patients were older than the rest of the NPM1mut AML cohort (mean age: 76 years; range: 65–87 years).

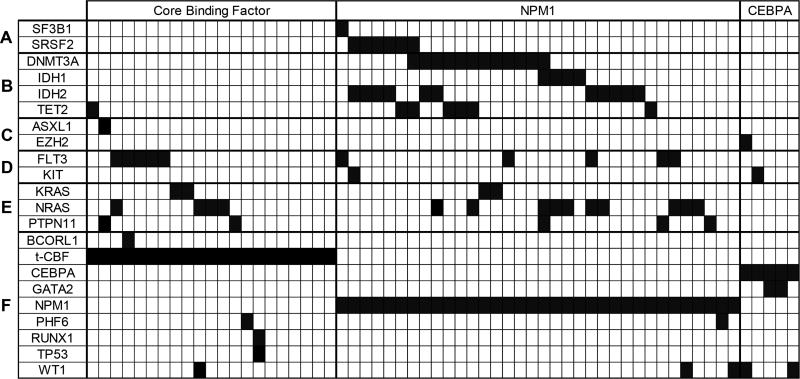

NPM1mut patients carried significantly more mutations compared to those in the other patients (P=0.0002; Table 2). Figure 1 shows the pattern of affected genes in different functional categories for each patient. These patterns differed significantly between the patient groups (Table 2). In particular, only NPM1mut patients carried mutations in genes involved in splicing, including SF3B1 and SRSF2 (P=0.048). Also, genes involved in DNA methylation, such as DNMT3A, IDH1, IDH2, and TET2, were much more commonly mutated in NPM1mut AML compared with the other groups (P<0.0001). CEBPAmut/mut patients had more mutations in genes related to transcriptional regulation, including GATA2 and WT1 (P=0.0006). There was no difference in mutation frequency in receptor, kinase, or RAS-related genes among the three groups.

Table 2.

Additional Gene Mutations by Subcategory

| CBF | NPM1 | CEBPA | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additional mutationsa | 1.0±0.2 | 2.1±0.2 | 1.2±0.2 | 0.0002 |

| Gene groupsb | ||||

| Splicing | 0 (0%) | 7 (21%) | 0 (0%) | 0.048 |

| Methylation | 1 (5%) | 26 (76%) | 0 (0%) | <0.0001 |

| Chromatin | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (20%) | n.s. |

| Receptor/Kinase | 5 (24%) | 6 (18%) | 1 (20%) | n.s. |

| RAS-related | 8 (38%) | 13 (38%) | 0 (0%) | n.s. |

| Transcription | 4 (19%) | 3 (9%) | 4 (80%) | 0.0006 |

Additional mutations exclude category defining mutations (CBF rearrangement and mutations in NPM1 or CEBPA);

The categories are based on those in Haferlach et al, 2014. The genes in each category are: Splicing – SF3B1, SRSF2, U2AF1, ZRSR2; Methylation – DNMT3A, IDH1, IDH2, TET2; Chromatin – ASXL1, EZH2; Receptor/Kinase – FBXW7, FLT3, JAK2, KIT, MPL; RAS-related – CBL, KRAS, NRAS, PTPN11; Transcription – BCOR, BCORL1, CEBPA, ETV6, GATA2, NPM1, PHF6, RUNX1, TP53, WT1.

Figure 1. Distribution of mutated genes in favorable-risk AML.

Each column represents an individual case of AML. The dark blocks indicate the genes mutated in the case. The lines are organized by functional category: A. Splicing; B. Methylation; C. Chromatin; D. Receptor/Kinase; E. RAS-related; F. Transcription. Only the genes that were mutated in these cases are shown. t-CBF, core binding factor translocation.

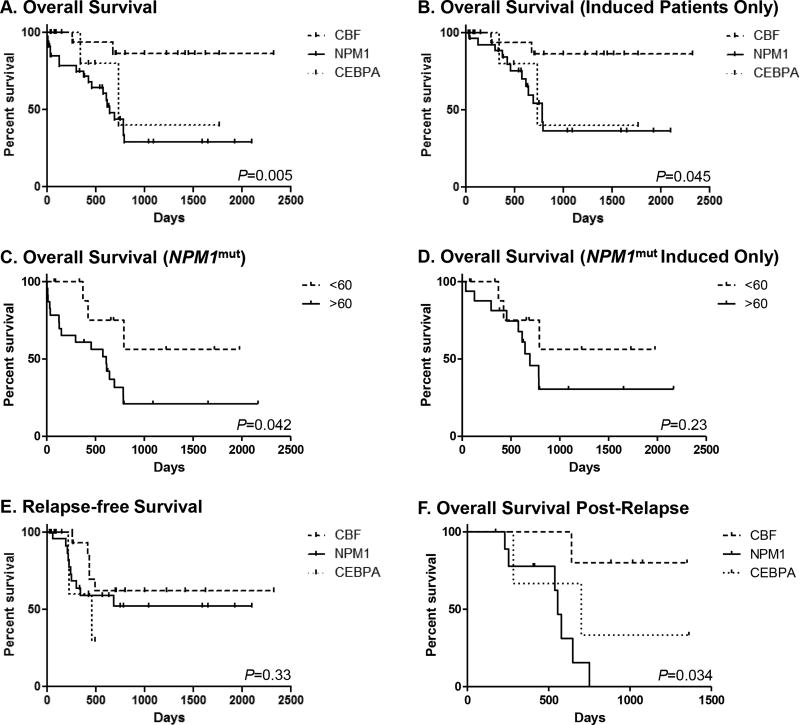

Of the patients who received induction chemotherapy, most (49/53; 92%) achieved CR (Table 3). All of those that did not achieve CR were in the NPM1mut category (P=0.048). There was a significant difference between favorable-risk groups in survival (Figure 2A), as NPM1mut and CEBPAmut/mut patients had poorer OS than CBF-KITwt patients (OS; P=0.005). This is borne out by univariate analysis, which shows CBF-KITwt as a positive and NPM1mut as a negative prognostic indicator (Table 4). In addition, presence of splicing and methylation gene mutations are associated with poor OS (Table 4).

Table 3.

Clinical Outcomes by Subcategory

| CBF | NPM1 | CEBPA | P (All) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete remissiona | 21/21 (100%) | 23/27 (85%) | 5/5 (100%) | n.s. |

| Median Overall Survival (d) | n.r. | 644 | 736 | 0.005 |

| Median Overall Survival (d) [induced patients only] | n.r. | 785 | 736 | 0.045 |

| Median Relapse-Free survival (d) | n.r. | 603 | 423 | n.s. |

d, days; n.r., median survival not reached.

Of those receiving induction chemotherapy.

Figure 2. Survival Curves.

Each panel shows a Kaplan-Meier survival curve comparing NPM1mut AML (solid lines), CBF-KITwt AML (dashed lines), and CEBPAmut/mut AML (dotted lines). A. Overall survival (OS) of all patients. B. OS for all patients that received induction chemotherapy (N=27 for NPM1mut AML; N=21 for CBF-KITwt AML; N=5 for CEBPAmut/mut AML). C. OS for NPM1mut patients by age. D. OS for NPM1mut patients that received induction chemotherapy by age. E. Relapse-free survival of patients who achieved complete remission (N=23 for NPM1mut AML; N=21 for CBF-KITwt AML; N=5 for CEBPAmut/mut AML). F. OS of relapsed patients measured from the date of relapse (N=10 for NPM1mut AML; N=5 for CBF-KITwt AML; N=3 for CEBPAmut/mut AML).

Table 4.

Univariate Survival Statistics by Age and Genotype

| OS | OS (Induced) | RFS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

P | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

P | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

P | |

| Age <60 | 0.18 (0.08–0.41) | <0.0001 | 0.23 (0.08–0.65) | 0.005 | 0.44 (0.16–1.2) | 0.12 |

| CBF | 0.27 (0.12–0.61) | 0.002 | 0.29 (0.11–0.76) | 0.01 | 0.52 (0.21–1.3) | 0.18 |

| NPM1 | 3.6 (1.6–8.0) | 0.002 | 2.9 (1.1–7.6) | 0.03 | 1.4 (0.56–3.6) | 0.46 |

| CEBPA | 0.96 (0.23–4.0) | 0.96 | 1.5 (0.27–7.9) | 0.66 | 2.3 (0.47–11.4) | 0.30 |

| Splicing | 5.0 (1.3–19) | 0.02 | 4.6 (0.93–23) | 0.06 | 1.5 (0.14–16) | 0.73 |

| Methylation | 2.9 (1.3–6.5) | 0.01 | 2.3 (0.85–6.0) | 0.10 | 1.5 (0.58–4.1) | 0.39 |

| Chromatin | 0.35 (0.04–3.2) | 0.35 | 0.35 (0.03–4.6) | 0.43 | 3.3 (0.18–63) | 0.42 |

| Receptor/Kinase | 1.1 (0.40–3.0) | 0.85 | 0.89 (0.27–3.0) | 0.86 | 0.70 (0.23–2.1) | 0.53 |

| RAS-related | 0.71 (0.31–1.6) | 0.42 | 0.54 (0.20–1.4) | 0.21 | 1.5 (0.58–4.1) | 0.39 |

| Transcription | 0.82 (0.30–2.2) | 0.70 | 1.2 (0.37–3.9) | 0.77 | 0.96 (0.32–2.9) | 0.94 |

As indicated above, 7 of 33 NPM1mut patients did not receive induction chemotherapy (Table 2); however, when these patients were excluded from the analysis, the significant difference in OS persisted (P=0.045; Figure 2B). Univariate analysis again shows a significant impact of CBF-KITwt and NPM1mut genotypes, but no other categories of gene mutation had significant impact on the prognosis of induced patients (Table 4).

In general, patients <60 years of age had better OS for both all patients and induced patients only (Table 4). To further analyze the effect of age, survival of NPM1mut patients greater and less than 60 years old (N=23 and 11, respectively) was compared to determine the impact of the more advanced age of these patients. Patients younger than 60 showed significantly better OS than their older counterparts (P=0.042; Figure 2C). However, this advantage was not clear when less aggressively treated patients (all of whom were older than 60) were excluded (P=0.23; Figure 2D).

There was no difference in relapse-free survival (RFS) in patients that achieved CR (P=0.33; Figure 2E; Table 4). However, relapse appeared to be more common in NPM1mut (10/23; 43%) and CEBPAmut/mut (3/5; 60%) patients than in CBF-KITwt patients (5/21; 24%). Further, while CBF-KITwt and CEBPAmut/mut patients all achieved a second complete remission, only 5 of 10 relapsed NPM1mut patients reached CR2. Consequently, post-remission HSCT for patients in CR2 was less common in NPM1mut (1/10; 10%) and CEBPAmut/mut (1/3; 33%) patients than in CBF-KITwt patients (3/5; 60%), and NPM1mut and CEBPAmut/mut patients exhibited lower post-relapse OS than CBF-KITwt (P=0.034; Figure 2F).

Discussion

In this study, we examined the genotypic and clinical characteristics of favorable-risk AML as defined by existing guidelines. The cytogenetic and molecular risk stratification models adopted by the NCCN and ELN are based on data from large-scale clinical trials, and early studies showed that AML patients with CBF translocations or APL showed significantly better response to therapy and improved survival compared to those with other cytogenetic findings, including normal karyotype (6,15,16).

Normal karyotype AML is a heterogeneous group in terms of prognosis, which may be further refined by molecular mutational analysis. For example, patients with FLT3 ITD or RUNX1 mutations have worse outcomes compared to others in this group (17–23). In contrast, NPM1mut AML patients were shown to have relatively good prognosis (8,9,24–26), reportedly comparable to those with CBF AML (23). Similarly, patients with normal karyotype that carry mutations in CEBPA also have relatively good outcomes (7,27,28), but this benefit appears to be restricted to those with biallelic mutations (29,30).

Data from the current study corroborates suggestions from other analyses that clinical outcomes are not evenly distributed across these favorable-risk entities. In particular, NPM1mut AML patients appeared to have significantly worse OS than those with CBF-KITwt AML (Figure 2A). OS was similar between CEBPAmut/mut AML and NPM1mut AML patients, and there was no difference in RFS (Figure 2C), although the number of CEBPA AML patients (N=5) limits comparisons with this cohort.

Survival comparisons between subtypes of favorable-risk AML are rare in the literature. Döhner et al. (24), found similar outcomes between NPM1mut AML patients and CBF AML patients. However, this comparison was indirect, between NPM1mut AML patients in one study and previously published CBF AML outcomes. Furthermore, it only looked at NPM1mut AML patients less than 60 years of age, which would exclude a significant number of NPM1mut AML patients. Schlenk et al. (28) showed similar outcomes between NPM1mut AML and CEBPAmut/mut AML, although it also excluded patients greater than 60 years old. This is in contrast to Dickson et al. (30), who showed more favorable outcomes for CEBPAmut/mut AML versus NPM1mut AML, specifically in older patients (>60 years old).

The precise factors responsible for these outcome differences are not certain. However, a number of factors may be considered. The NPM1mut AML patients in this study were significantly older than the CBF-KITwt AML or CEBPAmut/mut AML patients (Table 1). And age had a significant impact on OS in this study (Table 4). The median age of 65.5 is comparable, although slightly higher than that found for NPM1mut AML patients in other studies (8,26). Age is a negative prognostic factor in AML generally, in part because of poorer initial performance status and decreased likelihood of receiving intensive chemotherapy (31). For example, in the current study, 18% of NPM1mut AML patients, all of them older, did not receive induction chemotherapy, whereas 100% of patients with CBF-KITwt AML or CEBPAmut/mut AML were induced. This study is underpowered to perform multivariate analysis, which could potentially separate age from genotype effects on OS. However, when these non-induced patients were excluded from analysis, the differences in OS persisted (Figure 2B), and there was no difference in survival between NPM1mut patients older or younger than 60 years old that received induction (Figure 2D). This suggests that age may not be the only factor causing less favorable outcomes in NPM1mut patients. Larger studies will be required to determine the relative contribution of these factors.

It is interesting to note that while OS was significantly different between the groups, there was no difference in RFS (see Figure 2E). This discrepancy appears to be due to the fact that the CBF-KITwt patients had significantly better outcomes after relapse (Figure 2F). While all of them were able to achieve CR2, half of NPM1mut patients did not.

The genetic landscape of NPM1mut AML is another factor potentially contributing to the survival difference in favorable risk AML. This analysis shows that the NPM1mut AML is highly associated with increased number of co-mutated genes, particularly mutations in splicing and DNA methylation, when compared with CBF-KITwt AML and CEBPAmut/mut AML (Table 2 and Figure 1), a pattern that has been described in previous studies (19,32–34). Many of these genes, particularly DNMT3A, SF3B1, SRSF2, and TET2, are also amongst the most commonly mutated genes in myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) (14). This could indicate a common pathophysiology between NPM1mut AML and MDS that might contribute to the observed poorer outcomes. Alternatively, accumulation of mutations in these genes could be simply a marker of more advanced age, which NPM1mut AML and MDS share in common.

CBF-KITwt AML did not show a unique genotypic pattern in this study. The most commonly mutated genes were those in signal transduction pathways, such as FLT3 tyrosine kinase domain (TKD) and KRAS/NRAS, although these were similarly common in NPM1mut AML (Table 2 and Figure 1). Two recent large-scale studies have examined the mutational spectrum of CBF AML (37,38). Similar to the current study, these showed frequent mutation of FLT3 and KRAS/NRAS. Interestingly, they also demonstrated differences in mutation patterns between inv(16) and t(8;21) cases, which are not apparent in the current smaller study. KIT mutations are also common in CBF AML. However, there are convincing data indicating that these mutations predict worse RFS, particularly with t(8;21) (35,36). Consequently, such cases are generally considered intermediate risk and were intentionally excluded from this analysis (4).

CEBPAmut/mut AML appeared to be enriched in mutations of transcription-related genes, particularly GATA2 and WT1, which were either absent or less frequent in CBF-KITwt AML and NPM1mut AML. Only a few studies have attempted genomic characterization of CEBPAmut/mut AML. Greif et al. (39) demonstrated GATA2 mutations in more than one-third of these AML cases, and showed functional data suggesting cooperativity between the mutant GATA2 and CEBPA proteins during malignant transformation. Papaemmanuil et al. (33) also demonstrated frequent mutation of GATA2 (20%) and WT1 (21%) in CEBPAmut/mut AML.

Thus, overall, the genotyping performed in this study indicated differing patterns of co-mutation between the three categories of favorable-risk AML studied. There appears to be a baseline pattern of mutations in receptor/kinase and RAS-related genes that is common in both CBF-KITwt and NPM1mut AMLs (see Figure 1). These mutations are thought to drive survival and proliferation (so-called class I mutations), while the CBF and NPM1 mutations largely block myeloid differentiation (class II mutations) (40). The increase in additional mutations detected in NPM1mut AML appears to be due to more changes in splicing and methylation genes as indicated above, the latter which likely fall into a third class of mutations with epigenetic effects (41). Because patients with NPM1mut AML were significantly older, these mutation classes showed a similar age distribution (data not shown). As indicated above, CEBPAmut/mut AML demonstrate a co-mutation pattern that is distinct from the other two sub-categories, perhaps indicating a unique pathogenic mechanism. Outside of CBF, NPM1, and CEBPA, no other gene mutation category appeared to have an impact on OS when patients with common therapy were compared (Table 4).

There are some limitations to this study. The gene panel used in this study contains 37 genes, and although it covers a large proportion of genes commonly mutated in AML, there are some of clinical interest that are absent from the panel, such as the cohesin complex genes. Further analysis should take this into account. While the general therapeutic approach (7+3 induction followed by high-dose cytarabine consolidation) was similar in most cases, we were unable to control for all nuances in the treatment of individual patients in this retrospective study. However, the frequency of alternative treatment strategies, including HSCT and enrollment in clinical trials, did not differ significantly between the categories (see Table 1). Patients were included in this study regardless of age or eligibility for clinical trials. Thus, it adds an element of real-world clinical experience relevant to treatment decision-making for AML patients.

This study demonstrates significant differences in demographics, genotype, and clinical outcome between different sub-categories of favorable-risk AML. Confirmation of these findings will require additional larger studies. Yet the statistically significant differences between NPM1mut AML and other NCCN favorable-risk AMLs highlight the need to begin reconsidering the prognostic and therapeutic approach to these patients.

Highlights.

This study identified differences in the characteristics of favorable-risk AML.

AML with normal karyotype and NPM1 mutations is distinct in age and karyotype.

These patients have worse overall survival than other types of favorable-risk AML.

Further study is needed to determine if different treatment approaches are warranted.

Acknowledgments

The REDCap database tool is supported by grant UL1 TR000445 from NCATS/NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pulte D, Jansen L, Castro FA, Krilaviciute A, Katalinic A, Barnes B, et al. Survival in patients with acute myeloblastic leukemia in Germany and the United States: major differences in survival in young adults. Int J Cancer. 2016;139:1289–1296. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Döhner H, Weisdorf DJ, Bloomfield CD. Acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1136–1152. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1406184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, Thiele J, Borowitz MJ, Le Beau MM, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127:2391–2405. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. [Accessed January 20, 2017];NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology, Acute Myeloid Leukemia (Version 2.2016) https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/aml.pdf.

- 5.Döhner H, Estey E, Grimwade D, Amadori S, Appelbaum FR, Buchner T, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood. 2017;129:424–447. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-08-733196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grimwade D, Walker H, Oliver F, Wheatley K, Harrison C, Harrison G, et al. The importance of diagnostic cytogenetics on outcome in AML: analysis of 1,612 patients entered into the MRC AML 10 trial. The Medical Research Council Adult and Children's Leukaemia Working Parties. Blood. 1998;92:2322–2333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Preudhomme C, Sagot C, Boissel N, Cayuela JM, Tigaud I, de Botton S, et al. Favorable prognostic significance of CEBPA mutations in patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia: a study from the Acute Leukemia French Association (ALFA) Blood. 2002;100:2717–2723. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schnittger S, Schoch C, Kern W, Mecucci C, Tschulik C, Martelli MF, et al. Nucleophosmin gene mutations are predictors of favorable prognosis in acute myelogenous leukemia with a normal karyotype. Blood. 2005;106:3733–3739. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falini B, Nicoletti I, Martelli MF, Mecucci C. Acute myeloid leukemia carrying cytoplasmic/mutated nucleophosmin (NPMc+ AML): biologic and clinical features. Blood. 2007;109:874–885. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-012252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marcucci G, Mrozek K, Ruppert AS, Maharry K, Kolitz JE, Moore JO, et al. Prognostic factors and outcome of core binding factor acute myeloid leukemia patients with t(8;21) differ from those of patients with inv(16): a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5705–5717. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.15.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Appelbaum FR, Kopecky KJ, Tallman MS, Slovak ML, Gundacker HM, Kim HT, et al. The clinical spectrum of adult acute myeloid leukaemia associated with core binding factor translocations. Br J Haematol. 2006;135:165–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheson BD, Bennett JM, Kopecky KJ, Buchner T, Willman CL, Estey EH, et al. Revised recommendations of the International Working Group for diagnosis, standardization of response criteria, treatment outcomes, and reporting standards for therapeutic trials in acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4642–4649. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haferlach T, Nagata Y, Grossmann V, Okuno Y, Bacher U, Nagae G, et al. Landscape of genetic lesions in 944 patients with myelodysplastic syndrome. Leukemia. 2014;28:241–247. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slovak ML, Kopecky KJ, Cassileth PA, Harrington DH, Theil KS, Mohamed A, et al. Karyotypic analysis predicts outcome of preremission and postremission therapy in adult acute myeloid leukemia: a Southwest Oncology Group/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study. Blood. 200(96):4075–4083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Byrd JC, Mrozek K, Dodge RK, Carroll AJ, Edwards CG, Arthur DC, et al. Pretreatment cytogenetic abnormalities are predictive of induction success, cumulative incidence of relapse, and overall survival in adult patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia: results from Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 8461) Blood. 2002;100:4325–4336. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abu-Duhier FM, Goodeve AC, Wilson GA, Gari MA, Peake IR, Rees DC, et al. FLT3 internal tandem duplication mutations in adult acute myeloid leukaemia define a high-risk group. Br J Haematol. 2000;111:190–195. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gale RE, Green C, Allen C, Mead AJ, Burnett AK, Hills RK, et al. The impact of FLT3 internal tandem duplication mutant level, number, size and interaction with NPM1 mutations in a large cohort of young adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2008;111:2776–2784. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-109090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel JP, Gönen M, Figueroa ME, Fernandez H, Sun Z, Racevskis J, et al. Prognostic relevance of integrated genetic profiling in acute myeloid leukemia. New Engl J Med. 2012;366:1079–1089. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang JL, Hou HA, Chen CY, Liu CY, Chou WC, Tseng MH, et al. AML1/RUNX1 mutations in 470 adult patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia: prognostic implication and interaction with other gene alterations. Blood. 2009;114:5352–5361. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-223784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaidzik VI, Bullinger L, Schlenk RF, Zimmermann AS, Rock J, Paschka P, et al. RUNX1 mutations in acute myeloid leukemia: results from a comprehensive genetic and clinical analysis from the AML study group. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1364–1372. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.7926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schnittger S, Dicker F, Kern W, Wendland N, Sundermann J, Alpermann T, et al. RUNX1 mutations are frequent in de novo AML with noncomplex karyotype and confer an unfavorable prognosis. Blood. 2011;117:2348–2357. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-255976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mendler JH, Maharry K, Radmacher MD, Mrozek K, Becker H, Metzeler KH, et al. RUNX1 mutations are associated with poor outcome in younger and older patients with cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia and with distinct gene and microRNA expression signatures. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3109–3118. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.6652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Döhner H, Schlenk RF, Habdank M, Scholl C, Rucker FG, Corbacioglu A, et al. Mutant nucleophosmin (NPM1) predicts favorable prognosis in younger patients with acute myeloid leukemia and normal cytogenetics: interaction with other gene mutations. Blood. 2005;106:3740–3746. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verhaak RG, Goudswaard CS, van Putten W, Bijl MA, Sanders MA, Hugens W, et al. Mutations in nucleophosmin (NPM1) in acute myeloid leukemia (AML): association with other gene abnormalities and previously established gene expression signatures and their favorable prognostic significance. Blood. 2005;106:3747–3754. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thiede C, Koch S, Creutzig E, Steudel C, Illmer T, Schaich M, et al. Prevalence and prognostic impact of NPM1 mutations in 1485 adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) Blood. 2006;107:4011–4020. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fröhling S, Schlenk RF, Stolze I, Bihlmayr J, Benner A, Kreitmeier S, et al. CEBPA mutations in younger adults with acute myeloid leukemia and normal cytogenetics: prognostic relevance and analysis of cooperating mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:624–633. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schlenk RF, Döhner K, Krauter J, Frohling S, Corbacioglu A, Bullinger L, et al. Mutations and treatment outcome in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1909–1918. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Green CL, Koo KK, Hills RK, Burnett AK, Linch DC, Gale RE. Prognostic significance of CEBPA mutations in a large cohort of younger adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia: impact of double CEBPA mutations and the interaction with FLT3 and NPM1 mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2739–2747. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dickson GJ, Bustraan S, Hills RK, Ali A, Goldstone AH, Burnett AK, et al. The value of molecular stratification for CEBPADM and NPM1MUTFLT3WT genotypes in older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Br J Haematol. 2016;172:573–580. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Juliusson G, Antunovic P, Derolf A, Lehmann S, Mollgard L, Stockelberg D, et al. Age and acute myeloid leukemia: real world data on decision to treat and outcomes from the Swedish Acute Leukemia Registry. Blood. 2009;113:4179–4187. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-172007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paschka P, Schlenk RF, Gaidzik VI, Habdank M, Kronke J, Bullinger L, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are frequent genetic alterations in acute myeloid leukemia and confer adverse prognosis in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia with NPM1 mutation without FLT3 internal tandem duplication. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3636–3643. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.3762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Papaemmanuil E, Gerstung M, Bullinger L, Gaidzik VI, Paschka P, Roberts ND, et al. Genomic classification and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. New Engl J Med. 2016;374:2209–2221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1516192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patel JL, Schumacher JA, Frizzell K, Sorrells S, Shen W, Clayton A, et al. Coexisting and cooperating mutations in NPM1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res. 2016;56:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2017.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ayatollahi H, Shajiei A, Sadeghian MH, Sheikhi M, Yazdandoust E, Ghazanfarpour M, et al. Prognostic importance of c-KIT mutations in core binding factor acute myeloid leukemia: a systematic review. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2017;10:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.hemonc.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen W, Xie H, Wang H, Chen L, Sun Y, Chen Z, et al. Prognostic significance of KIT mutations in core-binding factor acute leukemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0146614. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duployez N, Marceau-Renaut A, Boissel N, Petit A, Bucci M, Geffroy S, et al. Comprehensive mutational profiling of core binding factor acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127:2451–2459. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-12-688705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Faber ZJ, Chen X, Gedman AL, Boggs K, Cheng J, Ma J, et al. The genomic landscape of core-binding factor acute myeloid leukemias. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1551–1556. doi: 10.1038/ng.3709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greif PA, Dufour A, Konstandin NP, Ksienzyk B, Zellmeier E, Tizazu B, et al. GATA2 zinc finger 1 mutations associated with biallelic CEBPA mutations define a unique genetic entity of acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2012;120:395–403. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-403220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Naoe T, Kiyoi H. Gene mutations of acute myeloid leukemia in the genome era. Int J Hematol. 2013;97:165–174. doi: 10.1007/s12185-013-1257-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shih AH, Abdel-Wahab O, Patel JP, Levine RL. The role of mutations in epigenetic regulators in myeloid malignancies. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:599–612. doi: 10.1038/nrc3343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]