Abstract

Objective: To examine the epidemiology of pediatric traumatic (TSCI) and acquired nontraumatic spinal cord injury (NTSCI) in Ireland. There are few studies reporting pediatric TSCI incidence and fewer of pediatric NTSCI incidence, although there are several case reports. As there is a single specialist rehabilitation facility for these children, complete population-level data can be obtained. Method: Retrospective review of prospectively gathered data in the Patient Administration System of the National Rehabilitation Hospital of patients age 15 years or younger at the time of SCI onset. Information was retrieved on gender, age, etiology, level of injury/AIS. Population denominator was census results from 1996, 2002, 2006, and 2011, rolled forward. Results: Since 2000, 22 children have sustained TSCI and 26 have sustained NTSCI. Median (IQR) age at TSCI onset was 6.3 (4.4) years, and at NTSCI onset it was 7.3 (8.1) years. Most common TSCI etiology was transportation (n = 10; 45.5%), followed by surgical complications (n = 8; 36.4%); most common injury type was complete paraplegia (n = 12; 54.5%) followed by incomplete paraplegia (n = 5; 22.7%). Most common NTSCI etiology was transverse myelitis (n = 11; 42.3%) followed by vascular (n = 5; 20%); most common injury type was incomplete paraplegia (n = 17; 65.4%) followed by incomplete tetraplegia (n = 6; 24%). Incidence of TSCI ranged from 0 to 3.1 per million per year; incidence of NTSCI ranged from 0 to 6.5 per million per year. Conclusion: Incidence of SCI in Ireland seems similar to or slightly lower than other developed countries. Injury patterns are also similar, considering variations in reporting methods.

Keywords: spinal cord dysfunction, spinal cord injury, pediatric

There is limited information in the literature about pediatric traumatic spinal cord injury (TSCI) and even less about acquired nontraumatic spinal cord injury (NTSCI). There is also considerable variability in reporting methods, such as the age range considered and whether those deceased prior to hospitalization are included. The only previous report of pediatric SCI incidence in Ireland formed part of a European study in 2006; incidence of TSCI among children in Ireland was estimated at 1.3 per million per year.1 Throughout Europe, the reported average cumulative incidence ranged from 0.9 to 27 per million per year, with only some countries including children who died prior to hospital admission.1 Individual studies in the state of Victoria, Australia, and in Sweden, Norway, and Finland also reported low average cumulative incidence of 1.9 to 4.6 per million, including fatalities.2–5 The reported cumulative incidence is much higher in the United States, where there were 14.8 to 20 cases per million per year from 2007 to 2010 in one study and 24 cases per million during 2009 in another.6,7 Adolescents account for a large proportion of pediatric TSCI – 41.9% to approximately two-thirds in the United States6,7 and 39.1 per million per year (of 15–19 year olds) in Norway.4 In most countries, the leading causes of injury are traffic incidents followed by sports.2,3,8 In Brazil, violence was the leading cause of TSCI in children9; this was also the case in the United States for males age 13 to 15 years.10 There are case reports and case series in the literature of TSCI sustained during childbirth and as a result of child abuse.11–13 Cervical level injuries are more common in younger children.8 Although the frequency of cervical and thoracic injuries is equally common throughout the age groups, approximately half of the injuries are complete.3

There is limited information about the incidence and etiology of NTSCI in children. However, there are several case reports citing the following etiologies: arteriovenous malformations, spinal cord infarction, tuberculosis, lymphoma, epidural hematoma, ganglioglioma, Wilms' tumour, and disc calcification with prolapse.14–23

Incidence of NTSCI in the North East of England and in Victoria, Australia, was reported at 4.3 (when TSCI cases are removed) and 6.5 per million, respectively.2,24 The most common etiologies are neoplasm and transverse myelitis with varying frequencies.2,9,24 Ireland has one of the highest rates of neural tube defects in the world, which is reported in terms of prevalence rather than incidence. Prevalence of spina bifida was reported at 0.51 per 1,000 total births for the period of 2009 to 2011 inclusive.25

The objective of this study was to examine the epidemiology of pediatric TSCI and acquired NTSCI in Ireland. There is only one specialist rehabilitation centre in Ireland for children who have acquired an SCI – the National Rehabilitation Hospital (NRH). Therefore, all cases of SCI are captured unless patients recover fully or are deceased before admission. This allows for the collection of complete population-based data.26

Methods

This retrospective study was carried out at the NRH, Dublin, Ireland. This is the only specialist service in Ireland for children who have sustained a TSCI or NTSCI. A database of all children attending the pediatric program has been maintained by the program since international accreditation of the hospital in 2008. Children who sustained a TSCI or NTSCI since 2000 were added retrospectively to this database; since 2008, they have been added prospectively. Case definitions for TSCI and NTSCI were based on the etiological classifications within the International Spinal Cord Society (ISCoS) core data set27 and NTSCI dataset.28 Children with spina bifida are not referred to the NRH and were not included.

Patients are considered children if they are 15 years old or younger at the time of injury. In the Irish health care service, an individual is considered to be a child until his or her 16th birthday, and referrals are made to pediatric rather than adult services. Once children were identified from the database, their health care records were retrieved and reviewed. Information was gathered on gender, age at onset, etiology, and level of injury/American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS).

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize variables by diagnosis. Categorical variables were described using frequencies and percentages. More advanced statistical analysis was not carried out, because the numbers in each diagnostic and etiological group were so low. For calculation of incidence, population denominator was census results from 1996, 2002, 2006, and 2011, each rolled forward until the next census occurred. National census figures are collected and retained by the Irish Central Statistics Office. From the census figures, it was possible to retrieve the number of individuals who were 16 years old and were living in Ireland at the time of each census, and these data were used in the calculation of incidence rates.

Results

Since 2000, 22 children (8 male, 14 female) have sustained a TSCI and 26 (10 male, 16 female) have sustained an NTSCI. Table 1 displays clinical and demographic features of the injuries. Median age at TSCI onset was 6.3 years (interquartile [IQR], 4.4); at NTSCI onset, it was 7.3 years (IQR, 8.1). Among TSCI patients, complete paraplegia was the most common injury subtype; for NTSCI, incomplete paraplegia was most common. In all cases, neurological examinations were carried out by doctors as early as possible in the admission of the children to rehabilitation.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic features of pediatric (age ≤15 years) traumatic spinal cord injury (TSCI) and nontraumatic spinal cord injury (NTSCI)

Transport incidents and transverse myelitis were the most frequent causes of TSCI and NTSCI, respectively. In the 10 cases of children involved in transport incidents, there were 2 cases in which lap-belt use was reported, 4 cases in which the children were reported to be restrained backseat passengers (1 in a booster seat), 3 cases for which no details of seating or restraint were given in the referral information, and 1 case of a pedestrian.

Of the children whose TSCI occurred following surgery, 7 of 8 had scoliosis surgery and 1 child had atlanto-axial subluxation. In 5 of the 7 scoliosis cases, the children had a syndromic condition and 1 had a preexisting acquired brain injury. Of the surgical cases, there were 4 osteotomies and posterior fusion; 1 anterior release and fusion; 1 halo application, thoracoplasty and release followed by fusion; 1 growth rod insertion/lengthening; and 1 case of suboccipital decompression. In 3 of the 8 surgical cases, there is documentation in the referral information of spinal cord monitoring having been carried out during surgery. There is reference to signal changes during surgery in only 1 case.

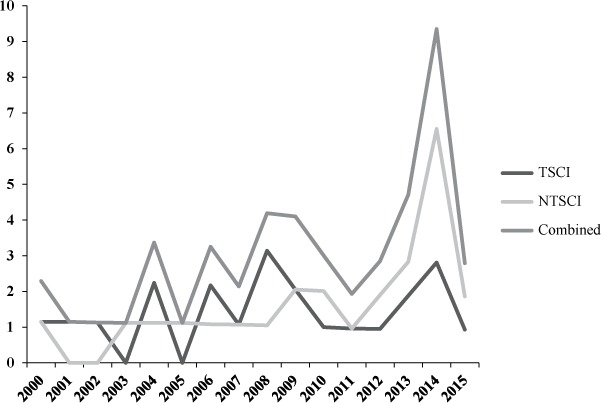

Annual cumulative incidence of TSCI from 2000 through 2015 ranged from 0 to 3.1 per million population per year and incidence of NTSCI ranged from 0 to 6.6 per million per year, as displayed in Figure 1. Average cumulative incidence, for the time period, was 1.4 per million per year for TSCI and 1.6 per million per year for NTSCI. In Table 2, the number of cases according to etiology is outlined for each year of the study period. Total prevalence of pediatric SCI in Ireland in 2015 was 31.7 cases per million, which equates to a total of 34 children.

Figure 1.

Incidence rate per million per year of pediatric traumatic (TSCI) and nontraumatic spinal cord injury (NTSCI).

Table 2.

Number of cases of each etiology of traumatic spinal cord injury (TSCI) and nontraumatic spinal cord injury (NTSCI) from 2000 to 2015 in Ireland

Discussion

During the study period, we found that incidence of pediatric TSCI in Ireland is low, as is the case in other developed countries where it has been reported.1–8 Incidence of NTSCI in our study is similar to that reported in the northeast of England (4.3 per million per year) and in Victoria, Australia (6.5 per million per year).2,24 Similar to our study, neither of these studies reports on spina bifida. There would appear to be an overall increase in incidence of both TSCI and NTSCI since the beginning of the study period, with a peak in incidence in 2014. It is difficult to hypothesize as to the reason, because each etiology of injury is rare. The low number of prevalent cases overall confirms the need for these children to continue to attend one specialist centre for lifelong care, where expertise in their management can be enhanced and sustained.

Paraplegia occurred more frequently than tetraplegia in both TSCI and NTSCI groups; this was also the case in some other studies of pediatric TSCI.3,4,9 There could be several reasons for this. Amongst children with TSCI, those sustaining tetraplegia may be more likely to be deceased prior to reaching hospital; amongst those with NTSCI in whom transverse myelitis is the most likely underlying etiology, incomplete paraplegia is a common outcome.29 The leading cause of TSCI throughout the study period was transport incidents, similar to many previous studies. In recent years, road safety strategies in Ireland seem to have had a notable positive impact30; transport incidents now appear to be an uncommon cause of TSCI in children, with just one case during the period 2010 to 2015 inclusive. Inappropriate restraint methods including lap-belt use has previously been cited as a potential cause of TSCI among children and adolescents.31,32 There were only 2 reported cases of lap-belt use in our study, although this may be an underestimation of its occurrence due to a lack of such detail in some of the referral information received. Iatrogenic causes accounted for a greater number of TSCI cases than reported in other studies. There are a few reasons why this might be the case. One of the risk factors for SCI following corrective scoliosis surgery is severity of the scoliosis, as measured by the Cobb angle.33 In Ireland, there has been a failure to invest adequately in many aspects of public health care for several years, including elective spinal deformity surgery for children.34 As a result, many children have highly advanced scoliosis by the time their surgery is performed, thereby increasing the risk of this complication. Second, we do not know whether intraoperative monitoring was carried out in all cases, as reference to its use was only noted in the referral information in 3 of the 8 cases. Intraoperative monitoring has been recommended since 2006 in all surgical procedures where there is a risk of causing neurological compromise.33 A final reason why we may have reported more cases of iatrogenic TSCI than previous reports is that studies that use emergency department or trauma registry data are unlikely to include this etiological group.6,7

The frequency with which transverse myelitis affected children is similar to that in the northeast of England whereas neoplasm was less common than that reported in Australia.2,24 Only a very small proportion of children with NTSCI in our study had complete SCI. The positive prognostic indicators for recovery have previously been identified for transverse myelitis,29 but these are not known in other nontraumatic causes. However, the number of incomplete injuries in our study suggests that many have a positive prognosis.

A major strength of this study is that there is a single specialist rehabilitation facility in Ireland for children who have acquired SCI; hence, all cases can be captured. One of the main limitations is that we do not include the number of children who were deceased prior to arrival at hospital, as these data are not available.

Pediatric SCI is rare in Ireland. The relative infrequency renders the collection of data on outcomes difficult. Comparison of our results with those in other countries is also challenging due to variable data collection and reporting methods. Plans for collaboration across multiple centers are vital and will enhance our knowledge in this area.35

REFERENCES

- 1. Augutis M, Abel R, Levi R.. Pediatric spinal cord injury in a subset of European countries. Spinal Cord. 2006; 44: 106– 112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Galvin J, Scheinberg A, New PW.. A retrospective case series of paediatric spinal cord injury and disease in Victoria, Australia. Spine. 2013; 38: 878– 882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Augutis M, Levi R.. Pediatric spinal cord injury in Sweden: Incidence, etiology and outcome. Spinal Cord. 2003; 41: 328– 336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hagen EM, Eide GE, Elgen I.. Traumatic spinal cord injury among children and adolescents; a cohort study in western Norway. Spinal Cord. 2011; 49: 981– 985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Puisto V, Kaariainen S, Impinen A.. Incidence of spinal and spinal cord injury and their surgical treatment in children and adolescents: A population based study. Spine. 2010; 35: 104– 107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Selverajah S, Schneider EB, Becker D, Sadowsky CL, Haider AH, Hammond ER.. The epidemiology of childhood and adolescent traumatic spinal cord injury in the United States: 2007 – 2010. J Neurotrauma. 2014; 31: 1548– 1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Piatt JH. Paediatric spinal injury in the US: Epidemiology and disparities. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2015; 16: 463– 471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Parent S, Mac-Thiong J-M, Roy-Beaudry M, Sosa JF, Labelle H.. Spinal cord injury in the pediatric population: A systematic review of the literature. J Neurotrauma. 2011; 28: 1515– 1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Costacurta MLG, Taricco LD, Kobaiyashi ET, Cristante ARL.. Epidemiological profile of a pediatric population with acquired spinal cord injury from AACD: Sao Paulo/Brazil. Spinal Cord. 2010; 48: 118– 121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. DeVivo MJ, Vogel LC.. Epidemiology of spinal cord injury in children and adolescents. J Spinal Cord Med. 2004; 27 suppl 1: S4– 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goetz E. Neonatal spinal cord injury after an uncomplicated vaginal delivery. Pediatr Neurol. 2010; 42: 69– 71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vialle R, Pietin-Vialle C, Vinchon M, Dauger S, Ilharreborde B, Glorion C.. Birth-related spinal cord injuries: A multi-centre review of nine cases. Childs Nerv Syst. 2008; 24: 79– 85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Feldman KW, Avellino AM, Sugar NF, Ellenbogen RG.. Cervical spinal cord injury in abused children. Paediatr Emerg Care. 2008: 24: 222– 227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McLaughlin M, Green M, Intradural spinal arteriovenous malformation in a 13-month old female: A case report. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2015; 8: 247– 250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bansal S, Brown W, Dayal A, Carpenter JL.. Posterior spinal cord infarction due to fibrocartilaginous embolization in a 16 year old athlete. Paediatrics. 2014; 134: 289– 292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bozzola E, Bozzola M, Magistrelli A, . et al. Paediatric tubercular spinal abscess involving the dorsal, lumbar and sacral regions and causing spinal cord compression. Infez Med. 2013; 21: 220– 223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stefan DC, Van Toorn R, Andronikou S.. Spinal cord compression due to Burkitt lymphoma in a newly diagnosed HIV-infected child. J Paediatr Haematol Oncol. 2009; 31: 252– 255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gupta V, Srivastava A, Bhatia B.. Hodgkin disease with spinal cord compression. J Paediatr Haematol Oncol. 2009; 31: 771– 773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hicdonmez T, Suslu HT, Yavuzer D, Tatarli N.. Paediatric ganglioblastoma of the conus medullaris. J Clin Neurosci. 2011; 18: 1124– 1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cabral AJ, Barros A, Aveiro C, Vasconcelos R.. Spontaneous spinal epidural haematoma due to arteriovenous malformation in a child. BMJ Case Rep. 2011; doi:10.1136/bcr.02.2011.3875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ramdial PK, Hadley GP, Sing Y.. Spinal cord compression in children with Wilms' tumour. Pediatr Surg Int. 2010; 26: 349– 353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee IC, Quek YW, Tsao SM, Chang IC, Sheu JN, Chen JY.. Unusual spinal tuberculosis with cord compression in an infant. J Child Neurol. 2010; 25: 1284– 1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bajard X, Renault F, Benharrats T, Mary P, Madi F, Vialle R.. Intervertebral disc calcification with neurological symptoms in children: Report of conservative treatment in 2 cases. Childs Nerv Syst. 2010; 26: 973– 978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sharpe AN, Forsyth A.. Acute paediatric paraplegia: A case series review. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2013; 17: 620– 624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McDonnell R, Delany V, O'Mahony MT, Mullaney C, Lee B, Turner MJ.. Neural tube defects in the Republic of Ireland in 2009 - 2011. J Public Health. 2015; 37: 57– 63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Smith E, Fitzpatrick P.. Epidemiology of spinal cord injury in Ireland. Part 1. Conference Proceedings, ISCoS/ASIA Joint Scientific Meeting; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27. DeVivo M, Biering-Sorensen F, Charlifue S, . et al. ; Executive Committee for the International SCI Data Sets Committees International Spinal Cord Injury Core Data Sets. Spinal Cord. 2006; 44: 535– 54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. New PW, Marshall R.. International spinal cord injury data sets for non-traumatic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2014; 52: 123– 132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. De Goede CGEL, Holmes EM, Pike MG.. Acquired transverse myelopathy in children in the United Kingdom – a 2 year prospective study. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2010; 14: 479– 487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Smith E, Brosnan M, Comiskey C, Synnott K.. Road collisions as a cause of traumatic spinal cord injury in Ireland 2001–2010. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2014; 20: 158– 165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Santschi M, Lemoine C, Cyr C.. The spectrum of seat-belt syndrome among Canadian children: Results of a two year population surveillance study. Paediatr Child Health. 2008; 13: 279– 283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Achildi O, Betz RR, Grewal H.. Lapbelt injuries and the seatbelt syndrome in pediatric spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2007; 30: S21– S24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sutter M, Deletis V, Dvorak J, . et al. Current opinions and recommendations on multimodal intraoperative monitoring during spine surgeries. Eur Spine J. 2007; 16 suppl 2: S232– S237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Delays still unacceptable in children's orthopaedic surgery – Press release. March 22, 2014. https://straighaheadireland.ie/media/press-releases/

- 35. Spinal cord injury in children and adolescents; identifying research priorities through an international service user survey. Conference Proceedings. ISCoS Scientific Meeting; 2014. [Google Scholar]