Abstract

Men who have sex with men (MSM) face a disproportionate burden of HIV incidence and HIV prevalence, particularly young men who have sex with men. The aim of this article was to analyze the relation between a psychological temporal perspective and HIV/sexually transmitted infection (STI) risk behaviors among male sex workers (MSWs), a potentially highly present-oriented group of MSM. A total sample of 326 MSWs were included and responded to a validated psychological scale: the Zimbardo’s Time Perspective Inventory; they also reported how frequently they engaged in protective behaviors against HIV and other STI risks behaviors, including condom use with casual and regular partners, as well as prior HIV testing. We adjusted structural equation models to analyze the relation between a psychological temporal perspective and HIV/STI risk behaviors. We found that orientation toward the past was correlated with decreased condom use with casual partners (β= −0.18; CI95% −0.23, −0.12). Future orientation was not associated with condom use with casual partners. Regarding condom use with regular partners, past and present orientation were related to lower likelihood of condom use (β= −0.23; CI95% −0.29, −0.17; β= −0.11; CI95% −0.19, −0.02), whereas future orientation increased the likelihood of condom use with regular partners (β=0.40; CI95% 0.31, 0.50). Time orientation (past, present, or future) did not predict the probability of having an HIV test. The design of HIV/STI prevention programs among vulnerable populations, such as MSM and MSWs, should consider specific time-frame mechanisms that can importantly affect sexual risk behavior decisions.

Keywords: Psychological time perspective, Time preference discounting, HIV/AIDS prevention, Sexually transmitted infection prevention, Mexico

Introduction

The prevalence of HIV in Mexico in the general population is 0.2%, as there were 220, 000 persons living with HIV in a country with an estimated population of 127.5 million people in 2016 (UNAIDS, 2017). Nevertheless, the epidemic is disproportionately concentrated among men who have sex with men(MSM) who had an HIV prevalence of 17% in 2011 (Bautista-Arredondo, Colchero, Romero, Conde-Gonzalez, & Sosa-Rubi, 2013). This prevalence is higher among specific MSM subgroups such as transvestite, transgender, and transsexual (TTT) with a prevalence of around 19.8% (Colchero et al., 2015; Infante, Sosa-Rubí, & Cuadra, 2009), and male sex workers (MSWs) with a prevalence above 30%(Galárraga et al., 2014a). Much of the literature has focused on examining the relationship between sexual risk behaviors among MSM and HIV and/or other sexually transmitted infections(STI). A specific subset of the MSM population, young men who have sex with men (YMSM), has been the focus of a growing body of research (Beidas, Birkett, Newcomb, & Mustanski, 2012; Chamberlain, Mena, Geter, &Crosby, 2016; Crosby, Mena, &Geter, 2016; Guo, Zhang, Wang, Chen, & Zheng, 2016; Hoenigl, Chaillon, Morris, & Little, 2016; Lee, Kim, Woo, Yoon, &Choi, 2016; Maksut, Eaton, Siembida, Driffin, &Baldwin, 2016). Yet research that seeks to understand the unique vulnerabilities of young male sex workers trying to understand their time perceptions remains limited (Galárraga et al., 2014a; Infante et al., 2009). In response to this public health need and taking into account the fact that MSWs have the highest HIV prevalence rates (Galárraga et al., 2014a), our study analyzes the relationship between a psychological temporal perspective and HIV/STI risk behaviors among MSWs.

In the economics literature, the notion of time has been incorporated in the analysis of time preferences using the discounted utility model, in which individual consumption in the present was assumed to be preferred to future consumption. Until recently, the analysis of discount rates (i.e., the rates at which individuals would trade present versus future consumption) relied on the assumption that those rates were consistent over time. Most recently, evidence showed that some decision-makers (most notably adolescents and others prone to engaging in risky behaviors) were more present biased and may exhibit hyperbolic discount rates (i.e., discount rates that may change over time) (Della Vigna, 2007; Loewenstein & Prelec, 1992; Story, Vlaev, Seymour, Darzi, &Dolan, 2014). Yetlittle is known about the time preferences and HIV/STI risks among MSWs.

Richer and multidimensional measures of temporal orientation may help to further characterize choices in the context of health in general and sexual risk behaviors in particular. One such measure comes from the psychology literature in the form of the Zimbardo’s Time Perspective Inventory (ZTPI) (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999). Based on this psychology-based theoretical view, decisions and human experiences may be parceled into temporal categories (or “time zones”)—usually past, present, and future. This temporal perspective could be learned from childhood, shaped by education, culture, social class, and experiences with economic and family stability-instability. An unbalanced temporal perspective would imply a biased temporal orientation that would favor one time frame over another (either present, past, or future). Following such path way, some individuals would become particularly oriented toward the past, the present, or the future (Boniwell & Zimbardo, 2015). Some evidence applying the ZTPI to analyze risky health behaviors has found that those individuals inclined toward the future decreased risky behaviors, while present hedonismis a strong predictor of health-destructive behaviors (Crockett, Weinman, Hankins, & Marteau, 2009; Henson, Carey, Carey, & Maisto, 2006). However, to our knowledge, time perspective using ZTPI has not been applied among MSWs who engage in risky behaviors.

Through this more nuanced concept of time, this article analyzes the decision to engage in preventative health behaviors to reduce risks for HIV and STI among MSWs—a particularly at-risk group. On the one hand, we can hypothesize that male sex workers may be more inclined toward a hedonistic present perspective and may be less likely to engage in preventative health as impatience and impulsivity may be correlated with sexual risk behaviors (such as inconsistent condom use and not knowing their own HIV/STI status). On the other hand, if some MSWs are more future oriented, they may be more likely to engage in protective behaviors.

Theoretical Considerations

In this section, we will summarize the main notions of time as presented in the economics and the psychology literature, respectively.

Discount Rate

Within the economics framework, we can assume that sexual risk behaviors (SRB) are normal goods (i.e., goods for which demand increases as income increases), and using prospect theory (Khwaja, Silverman, & Sloan, 2007) and simple discounting, we can set up an inter-temporal decision-maker’s problem as follows:

where the probability of engaging in protective behaviors (Y=1) is determined by the prospect of utility flows of sexual risk behaviors, SRBt, with probability pt in comparison with the prospect of disutility flows from reducing SRBt at each time period with probability qt, discounted by the discount factor δ.

This type of exponential discounting has been criticized in the literature particularly because it has to be consistent over time. Furthermore, the marginal utility of consumption at each time period t would depend not only on the level of consumption, but also on the relative consumption in relation to a reference point (Loewenstein & Prelec, 1992). An alternative, more realistic interpretation particularly for sexual risk behaviors may be that of hyperbolic discounting (Kang & Ikeda, 2014) which allows for individuals to be present biased.

Furthermore, other related research has pointed out that memories play an important role in current decision-making through endowment and contrast effects: Endowment, in this sense, is how the memories (good or bad) contribute to current well-being and choice making, whereas the contrast aspect refers to the way memories affect how we currently view the present situation in light of what we have already experienced (Golsteyn, Grönqvist, & Lindahl, 2014). Similarly, expectations about the future may be a critical factor in how we make choices in the present, and particularly in how we evaluate them; anticipation (“savoring” and “dread”) is an important element in the valuation of delayed consumption or desired behavior change that may go against current utility preferences (Borghans & Golsteyn, 2006; Dariotis & Johnson, 2015).

Research in economics has explored the so-called myopic behaviors (by which individuals may be heavily present biased), and it has been suggested that the rates of time discounting may not be the only temporal variables affecting choice (Jarmolowicz, Lemley, Asmussen, & Reed, 2015; Lawyer & Schoepflin, 2013). Our current analysis explores how an alternative measure of time perspective used primarily in psychological analyses, may relate to current decisions about sexual risk behaviors among a highly present-biased group of individuals.

Time Perspective

In the psychology literature, and according to Boniwell and Zimbardo (2015), time perspective represents an individual’s way of relating psychological concepts of past, present, and future based on the subjective experience of lived time. Time orientation represents a cognitive operation that requires an emotional reaction to abstract time zones (past, present, and future), and a preference of location in some temporal zone (Gorman & Wessman, 1977). The ZTPI assesses individual differences in terms of attitudes believed to identify persons of past, present, or future orientation. The ZTPI identifies tendencies toward a Hedonistic Present (living present life in enjoyment), a Fatalistic Present (perceiving own life under the control of external events), a Positive Past (anorientation toward pleasant past memories), a Negative Past (living a past of unpleasant and painful events), and Future Orientation (the tendency to planning and anticipating events) (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999). Zimbardo and Boyd have found that some individuals reveal dominant bias on one of the temporal perspective dimensions. The future-oriented individuals would focus their attention on consequences, contingencies, and probable outcomes of present decisions and actions: They would tend to be aware about all aspects that may contribute to a healthy life (eat healthy foods, get medical checkups, etc.). In contrast, a present-hedonistic person would tend to live in the moment, value hedonistic pleasure, enjoy high-intensity activities, seek thrills and new sensations, and be more open to sexual adventure. The present-fatalistic individual would be more prone to have feelings of hopelessness and would become fatalistic and resigned to the things that may happen in life. Alternatively, with a focus on family, tradition, and history, the past-oriented individuals could be either positive when individuals have a warm reference of past events, or negative for those individuals that focus on personal experiences that were noxious (Boniwell & Zimbardo, 2015).

Method

Participants

We used two convenience samples. First, we interviewed individuals at selected meeting places for male sex work in Mexico City(Galárraga, Sosa-Rubi, Infante, Gertler, & Bertozzi, 2014b). Selection of the study sites involved interviews with key informants of non-governmental organizations, researchers from the National Institute for Public Health, and the National Center for the Prevention and Control of AIDS. From an original sample of 1745 participants who responded to the section of willingness to participate in HIV prevention talks, we selected 220 individuals to collect additionally the ZTPI section, with particular emphasis on recruiting MSWs. Second, we used information from the baseline assessment of a randomized controlled pilot, Punto Seguro, to reduce risks among MSWs (Galárraga et al., 2014b). After eliminating missing values, we formed an analytical sample of n=326 individuals who either acknowledged themselves as working as male sex workers, or endorsed being MSM with more than 10 sexual partners in the last month, and having received money in exchange for sex in the past 6 months.

Measures

Response Variables

Condom Use

It was operationalized by asking subjects directly about their usual practice in terms of condom use during sexual intercourse with regular and with casual partners. Based on their responses, we generated two dummy variables that were equal to 1 if they agreed or strongly agreed with the statement endorsing consistent condom use:” I always use condoms” (with each casual and regular partners).

HIV Testing

For this variable, we generated a dichotomous variable based on the response of the subject to the question of whether he had ever undertaken an HIV test. The HIV testing variable was tested for validity and reliability in a prior study (Coates et al., 2000). The variable was equal to 1 if the response was positive and 0 otherwise.

Exposure Variable

The exposure variable was the latent variable Time Perspective, which reflects the cognitive relationship that people make between their lived experiences and their overall life goals. This variable was measured by the ZTPI (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999). The ZTPI is a validated scale that measures the beliefs, preferences, and values assigned to the past, present, and future, through 56 inventory items, with a five-option response scale to statements such as:

Past orientation: “I often think of what I should have done differently in my life”;

Present orientation: “Ideally, I would live each day as if it were my last”;

Future orientation: “I complete projects on time by making steady progress.”

The original scale consists of five factors that determine the positive or negative orientation toward the past or the present, or the future orientation (Copping, Campbell, & Muncer, 2014).

This inventory has been validated in Spanish by studies implemented in Spain (Díaz-Morales, 2006) and Argentina (Brenlla et al., 2013), finding that the psychometric properties of the ZTPI in particular cultural contexts, and the scales themselves reveal adequate internal consistency. In Mexico, the ZTPI has been applied to analyze time perspective and water conservation behavior among adults (Corral-Verdugo, Fraijo-Sing, & Pinheiro, 2006). In other contexts, there have been studies analyzing risk behaviors such as smoking and drug use and the ZTPI (Apostolidis, Fieulaine, Simonin, & Rolland, 2006; Keough, Zimbardo, & Boyd, 1999; Zimbardo, Keough, & Boyd, 1997);however, in the area of health risks, only few studies have analyzed the association between ZTPI with sexual-health-related behaviors among adults and young adults (Boyd & Zimbardo, 2005; Crockett et al., 2009; Henson et al., 2006).

Control Variables

We adjusted all models for the following control variables: socioeconomic status, education, age, age of first sexual intercourse, number of sexual partners, having a stable partner at the time of the interview, and reporting sex work as the main occupation. We estimated socioeconomic status by constructing an asset index generated using principal components analysis with a poly-choric correlation matrix.

Statistical Analysis

We used structural equation modeling(SEM)because the statistical data analysis included the presence of a latent variable. SEM contains two identifiable models: the measurement model and the structural model. The first one is basically a confirmatory factor analysis(CFA) in which the relations between every factor and their observed variables are specified (Bryant & Yarnold, 1995), and the validity of these relations is tested. High and significant coefficients (i.e., factor loadings) are indicators of convergent construct validity for the assessed factors. In turn, the structural model contains the relations between factors as well as the relations between observed and latent variables. In this study, our main interest was to estimate the association between the latent variable Time Perspective and one set of observed variables; namely, behaviors that could reduce the risk of HIV/STI, particularly condom use (with casual and regular partners) as well as HIV testing.

Measurement Model

We used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)to evaluate whether the multidimensional structure of the five originally defined ZTPI factors was adequate in our study population (Brown, 2015; Brown & Moore, 2015). We also checked the internal consistency and discriminatory power of each of the items of the scale. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients (Cronbach, 1951) were used to assess the internal consistency of the scale, which also can be interpreted as the reliability of every scale. To evaluate the discriminatory power of the items, we first calculated a general additive scale score and obtained its distribution in tertiles. Then, for each item, we evaluated by testing mean differences if the responses of individuals with overall score below the first tertile were different than those of individuals with an overall score above the third tertile of overall scale score distribution (Spector, 1992). If we found no significant differences, or if the Cronbach alpha coefficient suggested improved internal consistency of the scale when we excluded a particular item, then we considered that item irrelevant and excluded it from the subsequent analysis.

We proposed a reduced scale with the findings of the CFA, the internal consistency checks, and the discriminatory power analyses; and we analyzed its factor structure using exploratory factor analysis (EFA)(Fabrigar & Wegener, 2011). EFA attempts to bring inter correlated variables together under more general, underlying variables. More specifically, the goal of exploratory factor analysis is to explain the variance in the observed variables in terms of underlying latent factors. With the results of the EFA, we specified the following measurement model: the latent variable “time perspective” was measured by its observable indicators—three factors correlated with each other—to reflect the subjects’ temporal orientation toward the past, present, or future. The proposed structure recognized that people could get higher scores in different, interacting, time perspectives. Each person has a profile formed by the scores in the three perspectives and each perspective varies along a continuum from a low to a high score.

Structural Model

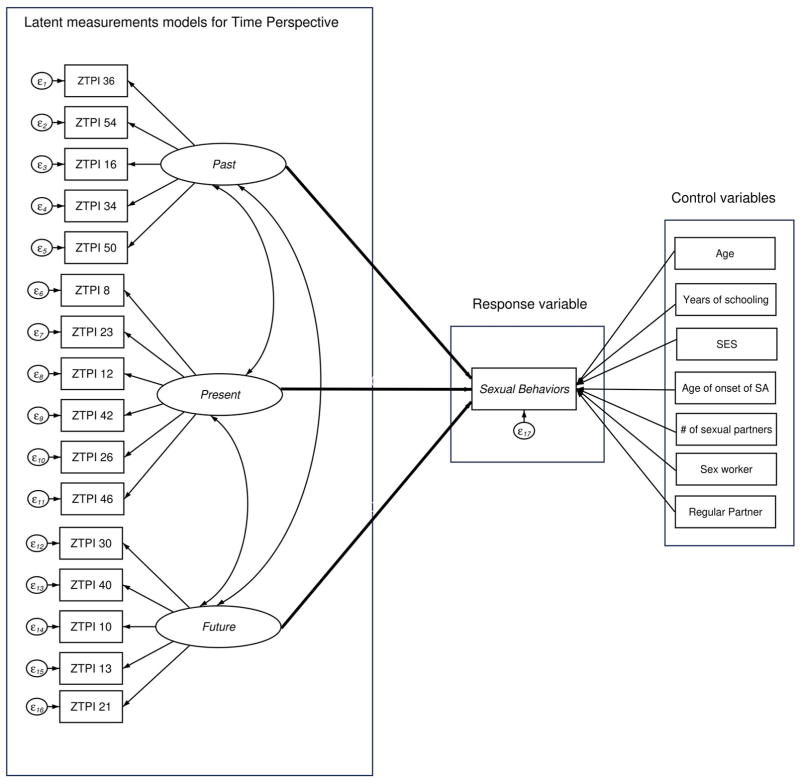

With our measurement model defined, we specified a structural model for each response variable—likelihood of condom use with regular partners, with casual partners, and the chance to having had an HIV test—relating it to the temporal orientation past, present, or future. Figure 1 shows the conceptual model that guided our empirical specification.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model: time perspective and safe sexual behaviors. Figures: rectangles are observable variables, ovals represent latent variables for time perspectives, and epsilons are errors for response variables. Arrows: The curved arrows between latent variables indicate that they are correlated. Boldface arrows are the structural coefficients between time perspective and sexual behaviors. Other straight one-headed arrows represent a direct relationship between two variables. ZTPI: standardized items from Zimbardo’s Time Perspective Inventory (number of item is included in label). Sexual behaviors: comprise condom use with casual or regular partners, and being tested for HIV. Latent variable: A variable in the model that is not measured directly. Error: The set of unspecified causes of the explained variable. Structural coefficients: the effect variable expected given a one unit change in the causal variable and no change in any other variable

In order to correlate results of the ZTPI scale score with the participants’ demographic information, indices representing those scales were computed. We grouped individuals in the sample according to the temporal orientation (past, present, future), which obtained the highest standardized score after adjusting the EFA model. We tested if there were significant differences among the three groups using the Kruskall–Wallis rank test for difference in medians of continuous variables and the chi-square test to evaluate the difference of proportions for categorical variables.

Estimation Method

The usual approach to estimate fit and coefficients in SEM is the maximum likelihood (ML) method. ML estimates are the ones that maximize the likelihood (the continuous generalization) that the data (the observed covariances) were drawn from this population. This method assumes that continuous response variables in the model are (conditionally)multivariate normal (i.e., the joint distribution of the variables is distributed normally). However, if the endogenous variables are not continuous or if their distributions are severely non-normal, then an alternative estimation method is needed. In our case, we estimated the structural models using the asymptotically distribution-free (ADF) estimation method, which main advantage is that it does not require multivariate normality (Acock, 2013; Bollen, 1989).

In addition, we evaluated the models using global goodness-of-fit statistics, chi-square test, and the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) test statistic. We also evaluated the comparative fit index with respect to the baseline model as a measure of incremental adjustment (Brown, 2015).

Sensitivity Analysis

Finally, to compare the results of our structural equation modeling with previous work, we conducted sensitivity analyses based on the economic approach to measuring time preference—evaluating the relationship between the discount rate (Loewenstein, 1987) reported by respondents and sexual behaviors that could reduce the risk of HIV/STI infection—using logistic regression models where the response variable was the reported behavior and the exposure was having a high discount rate (Golsteyn et al., 2014). All analyses were conducted in Stata 14.0 (College Station, Texas: Stata Corporation 2015) using the SEM (structural equation modeling) module.

Results

Respondents were young adults, with a median age of 23 years (IQR19–25), who had completed at least high school (median years of schooling was 12 years, IQR 12–17). Approximately, 57% of participants reported that sex work was their main occupation; however, among those with greater focus on the past, the percentage was 74%(p=.005).

The median age of onset of sexual activity was 15 years (IQR 13–17), and the median number of sexual partners during the week prior to the interview was 3 (IQR 1–6). Approximately, 40% of MSWs had a regular (stable) partner. As for sexual behaviors that could affect the risk of HIV infection, 70% of MSWs reported using condoms with casual partners and 71% with regular partners; in both cases, we found significant bivariate differences according to the time orientation, whereby MSWs who exhibited future orientation had higher rates of condom use. Finally, about 80% of MSW shad received an HIV test prior to the interview, and we observed no differences by the time orientation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socioeconomic and sexual risk characteristics

| Past orientation | Present orientation | Future orientation | p valuea | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=55 | N=95 | N=176 | N=326 | ||

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | ||

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||||

| Age | 23 (20–25) | 21 (19–24) | 23 (19.5–26) | <.001 | 23 (19–25) |

| Years of schooling | 12 (9–12) | 12 (9–12) | 12 (12–17) | <.001 | 12 (12–17) |

| Tertile of SES (%) | |||||

| 1st | 30.9 | 35.8 | 29.0 | .158 | 31.3 |

| 2nd | 49.1 | 44.2 | 47.7 | 46.9 | |

| 3rd | 20.0 | 20.0 | 23.3 | 21.8 | |

| Sexual risk | |||||

| Age of first sexual intercourse | 15 (13.5–17) | 15 (13–17) | 15 (14–18) | .392 | 15 (13–17) |

| Number of sexual partners | 4 (1–10) | 3 (1–6) | 2 (1–5) | .884 | 3 (1–6) |

| Percent with regular partner (%) | 38.2 | 38.9 | 43.2 | .864 | 41.1 |

| Percent of sex workers (%) | 74.6 | 55.8 | 52.3 | .005 | 57.1 |

| Condom use with casual partners | 67.2 | 58.9 | 76.7 | .004 | 69.9 |

| Condom use with regular partners | 58.1 | 68.4 | 76.7 | .023 | 71.2 |

| HIV testing | 83.3 | 74.1 | 77.3 | .386 | 77.4 |

IQR interquartile range

p value from Kruskall–Wallis or chi-square tests

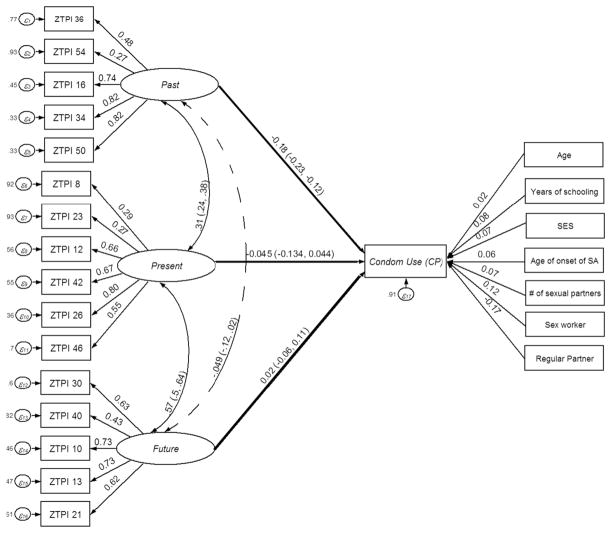

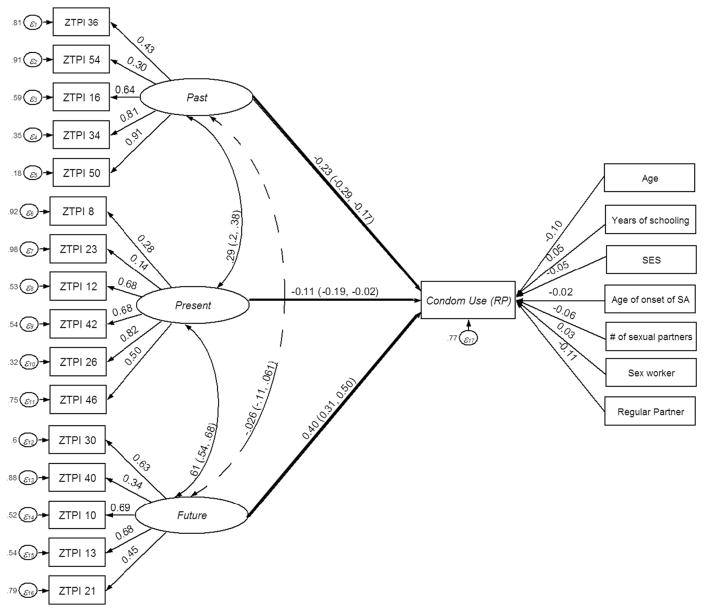

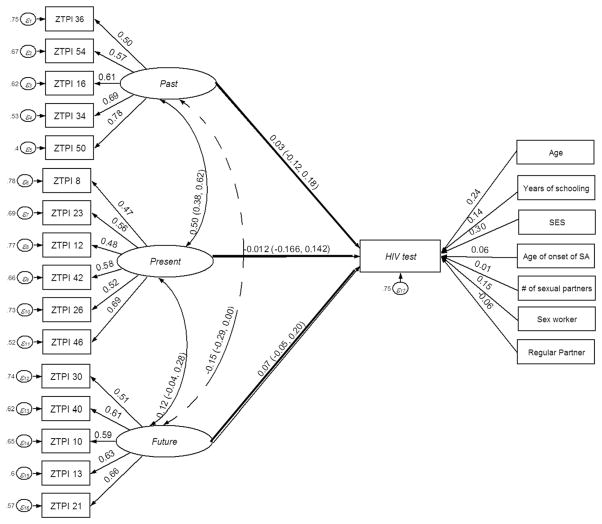

We specified three structural equation models to test our hypothesis. As shown in Figs. 2, 3, and 4, measurement model represents three correlated time perspectives measured by a set of items which load only in the factor that they were designed to measure. The fit of initial measurement model was acceptable. Most of the standardized factor loadings scoring above 0.4 and all the scores were statistically significant; also most of the standardized residuals were smaller than 0.50, providing relatively well goodness of fit. In all cases, we observed similar patterns of association between the temporal perspective orientations. Correlation coefficients among the three factors suggest that orientation toward the past was not significantly correlated with temporal orientation toward the future; however, both perspectives were correlated significantly with orientation toward the present. The relationship between present and future (r[324]=.61, p<.001) was stronger than the relationship between past and present (r[324]=.31, p<.001).

Fig. 2.

Structural equation model: time perspective and condom use with casual partners. CP casual partners. ZTPI Zimbardo’s Time Perspective Inventory (index item number). Dashed lines are statistically nonsignificant

Fig. 3.

Structural equation model: time perspective and condom use with regular partners. RP regular partners. ZTPI Zimbardo’s Time Perspective Inventory (index item number). Dashed lines are statistically nonsignificant

Fig. 4.

Structural equation model: time perspective and HIV testing. ZTPI Zimbardo’s Time Perspective Inventory (index item number). Dashed lines are statistically nonsignificant

The three models appear to perform a good fit to the data showing better adjustment than the null model of independence. The goodness-of-fit coefficients were similar among the models CFI around 0.99; CD over 0.99; and the SRMR less than 0.15 in all cases. We did not conduct post hoc modifications because of the good fit of the data to the model.

Regarding structural coefficients (shown in bold lines) for condom use with casual partners, the results show that higher scores in orientation toward the past were associated with lower probability of condom use (β= −0.18; CI95% −0.23, −0.12), while high scores on the temporal orientation toward the present or future were not significantly associated with casual partner condom use (Fig. 2).

Regarding condom use with regular partners, greater orientation toward the past and the present was significantly related to lower likelihood of condom use (β= −0.23; CI95% −0.29, −0.1723) and (β= −0.11; CI95% −0.19, −0.02). On the other hand, we observed that time perspective oriented toward the future increased the likelihood of condom use with regular partners(β=0.40; CI95% 0.31, 0.50) (Fig. 3).

Finally, we found no significant relationship between time orientation (past, present, or future) and the probability of having an HIV test prior to the interview (Fig. 4).

In sensitivity analyses based on the economic time preference variable, using the discount rate as a measure of the subjects’ impatience, we found no significant relationships between impatience and condom use (neither with regular partners nor with casual partners); and moreover, we did not find a relation of economic impatience with prior HIV testing (Table 2).

Table 2.

Safer sexual behavior and high discount rate

| Variable | ORa | Standard error | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Condom use with casual partners | 1.1 | 0.25 | .73 |

| Condom use with regular partners | 0.71 | 0.17 | .17 |

| HIV testing | 1.1 | 0.25 | .73 |

Odds ratios (OR) from logistic models, adjusted by age, SES, years of schooling, age of first sexual intercourse number of sexual partners, having a regular partner, and endorsing to engage in sex work as main occupation

Discussion

The objective of this study was to analyze the relation between a more nuanced “time perspective” construct and sexual risk behaviors in a particularly vulnerable population of male sex workers. MSWs are at high risk of STI/HIV acquisition and further transmission (Baral et al., 2015), particularly because of the market inducements for higher risk: They get paid higher prices for unprotected sex (Arunachalam & Shah, 2012; Galárraga et al., 2014a). The extant evidence has shown that MSWs engage in risky sexual behavior motivated by the additional premium(higher payment) they receive for having sex without condom; and that they are a subgroup of the population that, in general, may be focused on living the present day without considering the potentially deleterious future consequences of having unsafe sex with a client—a scenario in which they could be infected with HIV. Some studies in Mexico City have documented a high HIV prevalence (>30%) among young MSWs in low socioeconomic settings (Galárraga et al., 2014a) and their willingness to have unsafe sex for an additional premium (higher prices of by about 35%) (Galárraga et al., 2014a). This could be related to not only their economic necessity, but also their present bias. These unfavorable conditions make young MSWs in low socioeconomic settings in Mexico City more vulnerable to HIV acquisition—an aspect exacerbated by their proclivity for living the present.

We found that MSWs who were more inclined toward the present or the past perspectives would tend to get involved in more risky sexual behaviors (lower probability to use condom in a sexual intercourse). Additionally, MSWs oriented toward the future have a greater likelihood of condom use. In contrast, we did not find a significant association between the discount rate, as a proxy of impatience, with sexual risky behavior, which could reflect the lack of accuracy of this measure to reflect the different aspects of distinct constructs of temporal perspective (present, past, and future parcels) on individual’s health behavior.

This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first study documenting time perspective and HIV/STI risk behaviors among male sex workers. This study contributes to four strands of the literature. First, there is a small but rapidly growing body of research in health economics assessing the linkage of impatience and immediate gratification with risky behavior and poor health outcomes (smoking behaviors, alcohol and tobacco consumption, and body mass index BMI) (Borghans & Golsteyn, 2006; Golsteyn et al., 2014; Kang & Ikeda, 2014; Khwaja et al., 2007). More specifically, our study contributes to a small body of the literature that examines the relationship between delay discounting and sexual risk behaviors among young people, which reveals a significant association between increasing delay and certain sexual risk behaviors, such as decreased condom use and substance use (Dariotis & Johnson, 2015; Jarmolowicz et al., 2015; Lawyer & Schoepflin, 2013). Second, this study also contributes to an older and much larger literature in psychology, linking future orientation and healthier behaviors in general populations (Baumann & Odum, 2012; Copping et al., 2014; Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999). Third, we contribute to a growing set of public health research works that highlight the harmful effects of negative past orientation and the protective effects of future orientation, particularly among vulnerable populations such as young people and MSM (Abousselam, Naude, Lens, & Esterhuyse, 2015; Braitman & Henson, 2015; Dierst-Davies et al., 2011; Diiorio, Parsons, Lehr, Adame, & Carlone, 1993; Protogerou & Turner-Cobb, 2011; Rothspan & Read, 1996; Smit et al., 2006). Some of the limited literature that examines the relationship between temporal perspective and sexual risk behaviors reveals a positive association between future orientation and low sexual risk behaviors among college students (Diiorio et al., 1993; Richard, Van Der Pligt, & De Vries, 1996; Rothspan & Read, 1996), while others find no such association among African–American female juvenile detainees (Leeks, 2007). Additionally, this study expands the research that focuses on young male sex workers, who have a greater burden of HIV. Finally, this study contributes to the literature on inter-temporal choice and risk behaviors, more generally, by incorporating analytical tools from psychology and psychometrics.

The ZTPI, a validated psychological time perspective construct, seems to be able to predict the MSWs’ choice about engaging in preventative health behaviors measured as use of condom. From the point of view of prospect theory, choices with prospects of disutility from reduced sexual risk behaviors or decreased economic earnings (from lower commercial sex transaction prices) may be influenced not only by the time discount rate, but most importantly, by additional psychological factors such as the temporal orientation of the decision-makers.

On the one hand, orientation toward the past was associated with decreased condom use with both casual and regular partners. MSWs seem to make choices about their current and future HIV/STI risk strongly influenced by experiences in the past. This result is consistent with previous qualitative studies emphasized negative experiences related to sexual abuse, stigma, discrimination, and rejection (Infante et al., 2006, 2009). On the other hand, future orientation was positively associated with more protective behaviors, such as condom use, but not for HIV testing (as we had originally hypothesized). This result agrees with a previous study that used ZTPI to analyze HIV risk among heterosexual college students, concluding that those who score highly in future orientation have greater preventative health behaviors (delayed onset of sexual activity and relatively fewer sexual partners once active). Our results also seem to be in line with other health economics research that partially shows the beneficial effects of future orientation related to smoking behavior, BMI, and safe sex and drug use (Borghans & Golsteyn, 2006; Kang & Ikeda, 2014; Khwaja et al., 2007; Rotheram-Borus, Swendeman, & Chovnick, 2009).

Our study had several limitations. First, the sample was not representative of all MSWs in Mexico City, but as explained previously, it was a sample of convenience based on specific time and location. Nevertheless, even with a convenience sample, we were able to test our hypotheses about the usefulness of utilizing more nuanced psychometric measures of time perspective. Second, this study did not use biological measures and instead relies on self-reported outcomes, assuming that individuals’ responses are highly correlated with actual behavior and that they have no reason to conceal their true preferences. These assumptions, nevertheless, have been common in the literature almost from its conception (Crosby, 1998; Galárraga et al., 2014a).

Conclusion

In terms of the theory, time discounting models used in traditional economics may be enhanced by psychological constructs that may more accurately reflect the different effects of temporal perspectives. A more complete understanding of how decisions are made, particularly decisions about sexual risk behaviors, may help us to explore avenues to potentially modify hyperbolic preferences (de Walque, 2013; Perez-Arce, 2017). Time perspective could influence individuals’ motivations, actions, and final decisions to whether or not to engage in sexual risky behaviors. Characterizing the individuals’ time perspective could be a mechanism for improving the effectiveness of HIV prevention interventions among MSWs. This implies tailoring HIV prevention interventions taking into account the individuals’ time perspective to effectively promote behavior change: The modification of risky behaviors among MSWs with stronger future perspective orientation could require less intensive interventions (such as informational HIV campaigns to effect behavior change), while interventions among MSWs biased toward the hedonistic present may require more intensive interventions (such as behavior-based interventions to modify their risky sexual behaviors). These differentiated approaches have been suggested as prevention strategies among young adults with risky behaviors(Henson et al., 2006). In terms of public health practice, the design of HIV prevention programs among vulnerable populations, such as male sex workers, should consider specific mechanisms that affect the decisions to participate. The psychological temporal perspective and other factors can be specific aspects to consider in defining prevention campaigns to maximize participation, social welfare, and behavioral change.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants of Punto Seguro for responding to the questionnaires. We gratefully acknowledge all the Punto Seguro staff members; particularly, Nathalie Gras-Allain, Octavio Parra, and Jehovani Tena, as well as the clinical staff, particularly Dr. Arturo Martínez-Orozco and Dr. Florentino Badial-Hernández. Biani Saavedra, Fernando Ruiz, Cecilia Hipólito, and Gerardo Arteaga provided excellent research assistance. Edgar Ávila, Octavio Valente, Paola Olivieri, and interviewer sat La Mantade México, A.C. conducted data collection and field work for the formative phase. The Consortium for HIV/AIDS Research (CISIDAT, A.C.) provided project management and administration support. Useful comments at several stages of the research were provided by Stefano Bertozzi, Paul Gertler, Will Dow, Damien De Walque, César Infante, Julian Jamison, Nancy Padian, and Don Operario as well as participants at seminars at the National Institute of Public Health (INSP) and at the Ninth Workshop on Costs and Assessment in Psychiatry: Quality and Outcomes in Mental Health Policy and Economics, Venice, Italy, 2009.

Funding

Omar Galárraga has received grants from National Institutes of Health (K01-TW008016 and R21 HD065525) with additional support provided by the Mexican National Center for HIV/AIDS Control and Prevention (CENSIDA: Proy-2014-0262) and “Feasibility and willingness to participate in economic incentives program to prevent HIV/AIDS” (Targeted Prevention Programs for HIV/AIDS, FY 2008).

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Ethics Committee of Mexico’s National Institute of Public Health and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Participants received a detailed explanation of the procedures and signed an informed consent declaration before data collection occurred.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Abousselam N, Naudé L, Lens W, Esterhuyse K. The relationship between future time perspective, self-efficacy and risky sexual behaviour in the Black youth of central South Africa. Journal of Mental Health. 2015 doi: 10.3109/09638237.2015.1078884. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2015.1078884. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Acock AC. Discovering structural equation modeling using Stata. Stata Press books. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2013. (rev. ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Apostolidis T, Fieulaine N, Simonin L, Rolland G. Cannabis use, time perspective and risk perception: Evidence of a moderating effect. Psychology and Health. 2006;21(5):571–592. https://doi.org/10.1080/14768320500422683. [Google Scholar]

- Arunachalam R, Shah M. Compensated for life: Sex work and disease risk. Journal of Human Resources. 2012;48(2):345–369. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhr.2013.0015. [Google Scholar]

- Baral SD, Friedman MR, Geibel S, Rebe K, Bozhinov B, Diouf D, … Cáceres CF. Male sex workers: Practices, contexts, and vulnerabilities for HIV acquisition and transmission. Lancet. 2015;385(9964):260–273. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60801-1. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60801-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann AA, Odum AL. Impulsivity, risk taking, and timing. Behavioural Processes. 2012;90(3):408–414. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2012.04.005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista-Arredondo S, Colchero MA, Romero M, Conde-Glez CJ, Sosa-Rubí SG. Is the HIV epidemic stable among MSM in Mexico? HIV prevalence and risk behavior results from a nationally representative survey among men who have sex with men. PLo SONE. 2013 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072616. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0072616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Beidas RS, Birkett M, Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Do psychiatric disorders moderate the relationship between psychological distress and sexual risk-taking behaviors in young men who have sex with men? A longitudinal perspective. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2012;26(6):366–374. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0418. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2011.0418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Boniwell I, Zimbardo PG. Balancing time perspective in pursuit of optimal functioning. In: Joseph S, editor. Positive psychology in practice: Promoting human flourishing in work, health, education, and everyday life. 2. New York: Wiley; 2015. pp. 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118996874.ch13. [Google Scholar]

- Borghans L, Golsteyn BHH. Time discounting and the body mass index: Evidence from the Netherlands. Economics and Human Biology. 2006;4(1):39–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2005.10.001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd JN, Zimbardo PG. Time perspective, health, and risk taking. In: Strathman A, Joireman J, editors. Understanding behavior in the context of time: Theory research and application. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2005. pp. 85–107. [Google Scholar]

- Braitman AL, Henson JM. The impact of time perspective latent profiles on college drinking: A multidimensional approach. Substance Use and Misuse. 2015;50(5):664–673. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2014.998233. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2014.998233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenlla ME, Simmons M, Willis B, Ruarte F, Helou B, Gareis C, Andreo G, Broggi M. Adaptación Argentinadel Inventariode Perspectiva Temporal de Zimbardo (ZTPI). Paper presented at the International Congress of Research and Professional Practice in Psychology [V Congreso Internacional de Investigación y Práctica Profesional en Psicología]; Buenos Aires, Argentina: Facultad de Psicología, Universidad de Buenos Aires; 2013. Abstract retrieved from https://www.aacademica.org/000-054/918. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York: The Guilford Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Moore M. Confirmatory factory analysis. In: Hoyle R, editor. Handbook of structural equation modeling. New York: The Guilford Press; 2015. pp. 361–379. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant FB, Yarnold PR. Principal-components analysis and exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. In: Grimm LG, Yarnold PR, editors. Reading and understanding multivariate statistics. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1995. pp. 99–136. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain N, Mena L, Geter A, Crosby RA. Does age matter among young black men who have sex with men? A comparison of risk behaviors stratified by age category. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2016;28(3):246–251. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2016.28.3.246. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2016.28.3.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates TJ, Grnistead OA, Gregorich SE, Heilbron DC, Wold WP, Choi KH, … Furlonge C. Efficacy of voluntary HIV-1 counselling and testing in individuals and couples in Kenya, Tanzania, and Trinidad: A randomised trial. The Lancet. 2000;356(9224):103–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02446-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colchero MA, Cortés-Ortiz MA, Romero-Martínez M, Vega H, González A, Román R, Bautista-Arredondo S. HIV prevalence, sociodemographic characteristics and sexual behaviors among trans women in Mexico City. Salud Pública de México. 2015;57(Suppl 2):99–106. doi: 10.21149/spm.v57s2.7596. https://doi.org/10.21149/spm.v57s2.7596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copping L, Campbell A, Muncer S. Conceptualizing time preference: A life-history analysis. Evolutionary Psychology. 2014;12(4):829–847. https://doi.org/10.1177/147470491401200411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corral-Verdugo V, Fraijo-Sing B, Pinheiro JQ. Sustainable behavior and time perspective: Present, past, and future orientations and their relationship with water conservation behavior. Interamerican Journal of Psychology. 2006;40(2):139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Crockett RA, Weinman J, Hankins M, Marteau T. Time orientation and health-related behaviour: Measurement in general population samples. Psychology and Health. 2009;24(3):333–350. doi: 10.1080/08870440701813030. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440701813030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach L. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16(3):297–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310555. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby RA. Condom use as a dependent variable: measurement issues relevant to HIV prevention programs. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1998;10(6):548–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby RA, Mena L, Geter A. Are HIV-positive young black MSM having safer sex than those who are HIV-negative? International Journal of STD and AIDS. 2016;28(5):441–446. doi: 10.1177/0956462416651386. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956462416651386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dariotis JK, Johnson MW. Sexual discounting among high-risk youth ages 18–24: Implications for sexual and substance use risk behaviors. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2015;23(1):49–58. doi: 10.1037/a0038399. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Walque D. Risking your health: Causes, consequences, and interventions to prevent risky behaviors. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper. 2013;3362 https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-9906-4. [Google Scholar]

- Della Vigna S. Psychology and economics: Evidence from the field. Journal of Economic Literature. 2007;47(2):315–372. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.47.2.315. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Morales JF. Factorial structure and reliability of Zimbardo time perspective inventory. [Estructura factorial y fiabilidad del Inventario de Perspectiva Temporal de Zimbardo] Psicothema. 2006;18(3):565–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierst-Davies R, Reback CJ, Peck JA, Nuño M, Kamien JB, Amass L. Delay-discounting among homeless, out-of-treatment, substance-dependent men who have sex with men. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2011;37(2):93–97. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2010.540278. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2010.540278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diiorio C, Parsons M, Lehr S, Adame D, Carlone J. Factors associated with use of safer sex practices among college freshmen. Research in Nursing and Health. 1993;16(5):343–350. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770160505. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.4770160505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrigar LR, Wegener DT. Exploratory factor analysis. Oxford: Oxford University; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Galárraga O, Sosa-Rubí SG, Gonzalez A, Badial-Hernández F, Conde-Glez CJ, Juarez-Figueroa L, … Mayer KH. The disproportionate burden of HIV and STIs among male sex workers in Mexico City and the rationale for economic incentives to reduce risks. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2014a doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.1.19218. https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.17.1.19218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Galárraga O, Sosa-Rubi SG, Infante C, Gertler PJ, Bertozzi SM. Willingness-to-accept reductions in HIV risks: Conditional economic incentives in Mexico. European Journal of Health Economics. 2014b;15(1):41–55. doi: 10.1007/s10198-012-0447-y. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-012-0447-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golsteyn BHH, Grönqvist H, Lindahl L. Adolescent time preferences predict lifetime outcomes. Economic Journal. 2014;124(580):F739–F761. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12095. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman BS, Wessman AE. Images, values, and concepts of time in psychological research. In: Gorman BS, Wessman AE, editors. The personal experience of time. Emotions, personality, and psychotherapy. Boston, MA: Springer; 1977. pp. 215–263. [Google Scholar]

- Guo C, Zhang L, Wang Z, Chen G, Zheng X. Prevalence of and disparities in HIV-related sexual risk behaviours among Chinese youth in relation to sexual orientation: Across-sectional study. Sexual Health. 2016;13(4):383–388. doi: 10.1071/SH15190. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH15190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henson JM, Carey MP, Carey KB, Maisto SA. Associations among health behaviors and time perspective in young adults: Model testing with boot-strapping replication. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;29(2):127–137. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9027-2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-005-9027-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoenigl M, Chaillon A, Morris SR, Little SJ. HIV infection rates and risk behavior among young men undergoing community-based testing in San Diego. Scientific Reports. 2016;6:25927. doi: 10.1038/srep25927. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep25927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infante C, Sosa-Rubi SG, Cuadra SM. Sex work in Mexico: Vulnerability of male, travesti, transgender and transsexual sex workers. Culture, Health and Sexuality. 2009;11(2):125–137. doi: 10.1080/13691050802431314. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050802431314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infante C, Zarco A, Cuadra SM, Morrison K, Caballero M, Bronfman M, Magis C. HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: The case of health care providers in México [El estigma asociado al VIH/SIDA:El caso de los prestadores de servicios de salud en México] Salud Publica de Mexico. 2006;48(2):141–150. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342006000200007. Retrieved from http://saludpublica.mx/index.php/spm/article/view/6680/8313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarmolowicz DP, Lemley SM, Asmussen L, Reed DD. Mr. Right versus Mr. Right Now: A discounting-based approach to promiscuity. Behavioural Processes. 2015;115:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2015.03.005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang M, Ikeda S. Time discounting and smoking behavior: Evidence from a panel survey. Health Economics. 2014;23(12):1443–1464. doi: 10.1002/hec.2998. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.2998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keough KA, Zimbardo PG, Boyd JN. Who’s smoking, drinking, and using drugs? Time perspective as a predictor of substance use. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 1999;21(2):149–164. https://doi.org/10.1207/15324839951036498. [Google Scholar]

- Khwaja A, Silverman D, Sloan F. Time preference, time discounting, and smoking decisions. Journal of Health Economics. 2007;26(5):927–949. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.02.004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawyer SR, Schoepflin FJ. Predicting domain-specific outcomes using delay and probability discounting for sexual versus monetary outcomes. Behavioural Processes. 2013;96:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2013.03.001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DY, Kim SH, Woo SY, Yoon BK, Choi D. Associations of health-risk behaviors and health cognition with sexual orientation among adolescents in school. Medicine. 2016;95(21):e3746. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003746. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000003746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeks KD. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. Pro Quest Information & Learning; US: 2007. An examination of sexual risk behaviors and future time perspective among African American female juvenile detainees. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2007-99002-288&site=ehost-live. [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein G. Anticipation and the valuation of delayed consumption. The Economic Journal. 1987;97(387):666–684. https://doi.org/10.2307/2232929. [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein G, Prelec D. Anomalies in intertemporal choice: Evidence and an interpretation. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1992;107(2):574–597. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118482. [Google Scholar]

- Maksut JL, Eaton LA, Siembida EJ, Driffin DD, Baldwin R. An evaluation of factors associated with sexual risk taking among black men who have sex with men: A comparison of younger and older populations. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2016;39(4):665–674. doi: 10.1007/s10865-016-9734-x. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-016-9734-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Arce F. The effect of education on time preferences. Economics of Education Review. 2017;56:52–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2016.11.004. [Google Scholar]

- Protogerou C, Turner-Cobb J. Predictors of non-condom use intentions by university students in Britain and Greece: The impact of attitudes, time perspective, relationship status, and habit. Journal of Childand Adolescent Mental Health. 2011;23(2):91–106. doi: 10.2989/17280583.2011.634548. https://doi.org/10.2989/17280583.2011.634548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard R, Van Der Pligt J, De Vries N. Anticipated regret and time perspective: Changing sexual risk-taking behavior. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making. 1996;9(3):185–199. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0771(199609)9:3<185:AID-BDM228>3.0.CO;2-5. [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Swendeman D, Chovnick G. The past, present, and future of HIV prevention: Integrating behavioral, biomedical, and structural intervention strategies for the next generationof HIV prevention. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2009;5(1):143–167. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153530. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothspan S, Read SJ. Present versus future time perspective and HIV risk among heterosexual college students. Health Psychology. 1996;15(2):131–134. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.2.131. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.15.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit J, Myer L, Middelkoop K, Seedat S, Wood R, Bekker L, Stein DJ. Mental health and sexual risk behaviours in a South African township: A community-based cross-sectional study. Public Health. 2006;120(6):534–542. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.01.009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spector P. Summated rating scale construction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Story GW, Vlaev I, Seymour B, Darzi A, Dolan RJ. Does temporal discounting explain unhealthy behavior? A systematic review and reinforcement learning perspective. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2014 doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00076. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- UNAIDS. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS. 2017 Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/mexico.

- Zimbardo PG, Boyd JN. Putting time in perspective: A valid, reliable individual differences metric. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;6(77):1271–1288. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.77.6.1271. [Google Scholar]

- Zimbardo P, Keough K, Boyd J. Present time perspective as a predictor of risky driving. Personality and Individual Differences. 1997;23:1007–1023. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(97)00113-X. [Google Scholar]