SUMMARY

Under iron limitation, bacteria scavenge ferric (Fe3+) iron bound to siderophores or other chelates from the environment to fulfill their nutritional requirement. In gram-negative bacteria, the siderophore uptake system prototype consists of an outer membrane transporter, a periplasmic binding protein, and a cytoplasmic membrane transporter, each specific for a single ferric siderophore or siderophore family. Here, we show that spontaneous single gain-of-function missense mutations in outer membrane transporter genes of Bradyrhizobium japonicum were sufficient to confer on cells the ability to use synthetic or natural iron siderophores, suggesting that selectivity is limited primarily to the outer membrane and can be readily modified. Moreover, growth on natural or synthetic chelators required the cytoplasmic membrane ferrous (Fe2+) iron transporter FeoB, suggesting that iron is both dissociated from the chelate and reduced to the ferrous form within the periplasm prior to cytoplasmic entry. The data suggest rapid adaptation to environmental iron by facile mutation of selective outer membrane transporter genes and by non-selective uptake components that do not require mutation to accommodate new iron sources.

ABBREVIATED SUMMARY

Unlike E. coli, selectivity for uptake of nutritional iron chelates is limited to the outer membrane in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Gain-of-function mutations in genes encoding outer membrane transporters are sufficient to allow B. japonicum to readily adapt to new iron sources in the environment.

INTRODUCTION

Iron is an essential nutrient, but bioavailability is low in aerobic environments because it forms insoluble ferric hydroxides. Many bacteria and fungi secrete low-molecular-weight, high affinity molecules called siderophores to bind ferric iron, and subsequently transport the ferric-siderophore complex into bacterial cells (Chu et al., 2010, Miethke & Marahiel, 2007). Bacteria may also take up siderophores made by other microbes, and are called xenosiderophores in that context. Siderophore synthesis and uptake proteins are virulence factors for pathogenic bacteria, and are potential targets for antimicrobial therapy (Alteri et al., 2009, Brumbaugh et al., 2013, Mike et al., 2016).

In Gram-negative bacteria, the Fe3+-siderophore uptake paradigm consists of an outer membrane transporter, a periplasmic binding protein and a cytoplasmic membrane transporter (Payne et al., 2016, Schalk & Guillon, 2013, Andrews et al., 2003, Noinaj et al., 2010). These components are specific for one or a limited number of structurally similar siderophores. The uptake of exogenous heme for utilization as an iron source is taken up by a similar system.

The outer membrane transporters are gated channels that require TonB and other auxiliary proteins to transduce energy of the proton motive force from the cytoplasmic membrane to the transporter (Faraldo-Gomez & Sansom, 2003). Although they share only modest amino acid sequence similarity, the overall domain architecture is the same (Chimento et al., 2005, Krewulak & Vogel, 2008, Noinaj et al., 2010). These transporters are transmembrane β-barrel proteins consisting of 22 β-sheets forming the channel, loops that extend into the extracellular space, and an N-terminal plug that resides within the pore.

Bradyrhizobium japonicum lives freely in soil or as an endosymbiont of soybean in root nodules. B. japonicum USDA110 does not synthesize siderophores, but can utilize xenosiderophores (Plessner et al., 1993, Small et al., 2009) and heme (Noya et al., 1997) as iron sources. The lack of synthetic capacity for siderophores has been demonstrated in other bacteria, and is probably not uncommon (Dhaenens et al., 1999, Williams et al., 1990, D’Onofrio et al., 2010, Rohde & Dyer, 2003). B. japonicum expresses one outer membrane heme transporter (Nienaber et al., 2001) and five ferric siderophore transporters (Small & O’Brian, 2011, Small et al., 2009). Iron limitation is sufficient to transcriptionally induce the six genes encoding those proteins (Nienaber et al., 2001, Small et al., 2009) The periplasmic and inner membrane components in heme uptake have been identified (Nienaber et al., 2001), but corresponding proteins in siderophore uptake have not been described, nor are genes for them apparent in the B. japonicum genome.

In the present study, we demonstrate that B. japonicum can rapidly adapt to iron stress through mutation to allow the utilization of new iron sources in the environment.

RESULTS

Gain-of-function mutations in siderophore transporter genes confer the ability to utilize the synthetic chelator ethylenediaminedi [o–hydroxyphenylacetic] acid (EDDHA) as a siderophore for scavenging iron

EDDHA is a synthetic metal chelator. B. japonicum and other bacteria do not grow on solid media containing EDDHA because it binds nutritional iron and prevents it from entering cells. The EDDHA-induced growth defect can be rescued by supplementation with an excess of an iron salt or with heme (Escamilla-Hernandez & O’Brian, 2012, Amarelle et al., 2010, Nienaber et al., 2001) (Fig. 1). Here, B. japonicum cells were spread on solid agar media containing 100 μM EDDHA, and 6 colonies arose spontaneously after 21 days of incubation (frequency of ~10−7). Colonies normally arise in about 7 days in the absence of the chelator. Three of the mutants retained the ability to grow on EDDHA after re-streaking.

FIGURE 1. Dominant gain-of-function mutations in siderophore outer membrane transporter genes rescue growth on the synthetic iron chelator EDDHA.

Cells were serial diluted, and 5 μl aliquots were spotted onto plates 20 μM FeCl3 (A), 100 μM EDDHA (B), 100 μM EDDHA plus 20 μM FeCl3 (C), 20 μM DTPA (D), 20 μM DTPA and 100 μM EDDHA (E) or 20 μM DTPA with 20 μM FeCl3 (F). The strains entR(L272P), entR(T437P) and fegA(L497Q) represent the isogenic siderophore transporter mutants reconstructed in the wild type background. Strains entR(L272P)+, entR(T437P)+ and fegA(L497Q)+ denote the partial diploids harboring the wild type copy and the designated mutated copy of the transporter, integrated in the wild type genome.

The three mutants and the wild type were genotyped by whole genome DNA sequencing. (Table S1). Each strain harbored several mutations, including a single point mutation in a gene encoding an outer membrane ferric siderophore transporter resulting in a single amino acid substitution (Table S1). Those mutations were verified by re-sequencing PCR-amplified regions. The mut7 allele harbors a L497Q mutation in the fegA gene encoding the outer membrane ferrichrome transporter. mut2 and mut6 contain mutations in the putative outer membrane transporter gene blr3904 gene resulting in L272P and T437P substitutions, respectively, in the encoded protein. Genetic evidence described below indicates that blr3904 encodes the outer membrane transporter for the catecholate siderophore enterobactin, and thus it is designated entR here.

The three mutations, entR(L272P), entR(T437P) and fegA(L497Q) were reconstructed in the wild type background to obtain isogenic strains, and growth phenotypes were confirmed in a spotting assay (Fig. 1). Whereas growth of the wild type was inhibited by EDDHA, the mutants grew well under those conditions, in agreement with the growth phenotype of the original mutants (Fig. 1A, B). Inhibition of the wild type by EDDHA was rescued by the addition of 20 μM FeCl3 to the medium (Fig. 1C). The mutants harboring the entR and fegA allele variants also retained the ability to use enterobactin and ferrichrome, respectively (Fig. S1). Because the outer membrane transporter gene alleles were sufficient to confer growth on EDDHA similar to the original mutants, we did not investigate other mutations found within the mut2, mut4 or mut7 genomes (Table S1).

To assess whether the wild type or mutant allele was dominant, partial diploids were constructed that contained the wild type fegA or entR genes in addition to the corresponding mutant allele. The partial diploids grew well in the presence of EDDHA (Fig. 1A, B), showing that the mutant alleles are dominant.

We wanted to address the idea that mutations in the outer membrane transporters confer on cells the ability to use EDDHA as a siderophore to scavenge extracellular iron. Diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) is another synthetic iron chelator that sequesters ferric iron in the media and prevents bacterial iron import (Gu & Imlay, 2013). Growth of the wild type and mutants were inhibited on agar medium containing 20 μM DTPA. Supplementation with 100 μM EDDHA to the media containing DTPA restored growth of the strains with the altered siderophore transporter allele entR(L272P), entR(T437P) or fegA(L497Q) but not the wild type (Fig. 1E). Thus, EDDHA was not only tolerated by the mutants, it was able to rescue growth under iron deprivation. These observations suggest that EDDHA may act as a siderophore that scavenges iron, and that the mutant transporters confer on cells the ability to use the chelated metal it as an iron source. EDDHA is structurally dissimilar to ferrichrome or enterobactin (Fig. S2), yet a single missense mutation in the cognate transporter FegA or EntR, respectively, was sufficient to confer growth on EDDHA.

Identification of TonB2 and its requirement for utilization of the synthetic chelator EDDHA

A hallmark of ferric chelate transport in gram-negative bacteria is a requirement for the TonB protein to transduce energy from the cytoplasmic membrane to the outer membrane transporter for active transport of the ligand (Postle & Kadner, 2003). The genome of B. japonicum USDA110 contains two tonB gene homologs. One of them was shown to be required in heme utilization and dispensable for siderophore uptake (Nienaber et al., 2001), whereas the other homolog (blr3908) has not been characterized. We found that the blr3908 mRNA was induced in cells grown under iron limitations as determined by qPCR analysis (Fig. S3). This expression pattern is qualitatively similar to the expression pattern of siderophore transporter genes (Fig. S3 and (Small et al., 2009)).

We constructed a blr3908 deletion mutant and tested its growth on different siderophores. The blr3908 mutant grew poorly on the siderophores ferrichrome, enterobactin and desferrioxamine (Fig. 2). fegA is the ferrichrome transporter gene (Small et al., 2009, LeVier & Guerinot, 1996), and we show here that EntR and FhuE support growth on enterobactin and desferrixomanine, respectively, as observed by growth phenotypes of the entR and fhuE mutants (Fig. 2). The blr3908 strain grew well with heme as the iron source, confirming that it is not necessary for heme uptake.

FIGURE 2. Requirement of tonB2 for growth on natural siderophores or EDDHA.

Serial dilution and spotting on plates of modified GSY media containing 10 μM heme (A), 100 μM EDDHA (B), 4 μM ferrichrome (C), 4 μM enterobactin (D) or 25 μM desferrioxamine (E). The tonB2 and entR(L272P) tonB2 strains have an in-frame deletion in the tonB2 (blr3908) gene in the wild type and entR(L272P) background respectively. The fegA, entR and fhuE strains are defective in the respective ferric-siderophore transporters.

We measured uptake activities of 59Fe3+ bound to enterobactin, ferrichrome or desferrioxamine in the wild type and tonB2 mutant (Figs. 3A–C). The activities observed in the wild type strain were mostly abrogated in the tonB2 mutant, in agreement with the growth phenotypes of that mutant on those iron sources. We suggest that Blr3908 is the TonB homolog that interacts with FegA, EntR and FhuE for uptake of their cognate siderophores, and we designate the gene as tonB2 to distinguish it from the tonB associated with heme transport.

FIGURE 3. Uptake of siderophore-mediated 59Fe3+.

Uptake of 59Fe3+- siderophores was measured in the cells of the wild type, tonB2 and feoB strains along with the respective siderophore transporter mutant entR, fegA or fhuE. Cells were suspended in uptake buffer containing 4 μM enterobactin (A), 4 μM ferrichrome (B) or 25 μM desferrioxamine (C). At time 0, 25 nM 59Fe3+ was added to the cell suspension, and aliquots were subsequently collected at 0, 10, 50 minutes to measure counts. Each time point is the average of three biological replicates ± S.D. (error bars) after subtracting the 0 minute reading.

To determine whether EDDHA utilization by the mutants relies on TonB2, we generated a tonB2 mutant in the entR(L272P) background. Loss of the tonB2 gene abrogated the ability of the entR(L272P) mutant to grow with EDDHA (Fig. 2), and thus EDDHA utilization is TonB2-dependent. This further supports a role for EntR (L272P) in utilization of EDDHA as a siderophore.

The mutants that arose on plates with EDDHA did not grow in liquid media with the chelator. It is plausible that the iron requirement on plates is less than for liquid media. In support of this, we observed that wild type cells grow on minimal media plates with noble agar, but much more poorly in liquid in minimal media (Fig. S4). Moreover, uptake of 59Fe3+-EDDHA by cells grown in liquid culture (without EDDHA) could not be reliably measured. It is likely that EDDHA-mediated uptake of iron is very low, but sufficient to support growth on plates. Nevertheless, these observations led us to address two hypotheses: First, outer membrane transporters are readily adaptable through mutation to accommodate new iron chelates. Second, selectivity for siderophore utilization is limited primarily to the outer membrane in B. japonicum, suggesting common components in the periplasm and cytoplasmic membrane.

Identification of gain-of-function mutations in the outer membrane heme transporter gene hmuR that suppress the growth phenotype of an fhuE mutant

We wanted to further test the idea that outer membrane transporters can readily adapt through mutation using a natural siderophore. The fhuE gene encodes the desferrioxamine transporter, thus an fhuE mutant cannot grow on desferrioxamine as an iron siderophore (Fig. 4A) or take up 59Fe3+-desferrioxamine (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4. Gain-of-function mutations in the heme transporter gene hmuR suppress the growth and Fe3+ uptake phenotypes of an fhuE mutant on desferrioxamine.

(A) Growth of mutants on desferrioxamine. Cells were serially diluted, and 5 μl aliquots were spotted onto plates containing 20 μM FeCl3 (a), 25 μM desferrioxamine (b) or 25 μM desferrioxamine plus 20 μM FeCl3 (c). Strains with a + sign denote partial diploids with both the wild type and the mutated hmuR allele integrated into the genome.

(B) 59Fe3+- desferrioxamine uptake. Cells of the wild type (open square), fhuE (closed square), fhuE hmuR(W351R) (open triangle), fhuE hmuR(Δ182-193) (open circle) and fhuE hmuR (Δ403-425) (closed circle) strains were suspended in uptake buffer containing 25 μM desferrioxamine (a) or 20 mM sodium-citrate (b). At time 0, 50 nM 59Fe3+ was added to the cell suspension, and aliquots were subsequently taken at various time points and counted. Each time point is the average of three biological replicate samples ± S.D. (error bars).

Cells of the fhuE strain were plated onto media containing desferrioxamine, and colonies that arose spontaneously after 17 days were picked (frequency of ~10−7). We genotyped three of the suppressor mutants that grew well on desferrioxamine, and found that each strain contained multiple mutations (Table S2). Each suppressor harbored a unique mutation within the hmuR gene encoding the heme transporter (Table S2). The sup1 strain contains a point mutation in the hmuR gene resulting in W351R variant. Suppressors 2 and 4 have in-frame deletions in the hmuR gene encoding proteins with deletions of amino acid residues 182-193 and 403-425 respectively. The suppressor alleles were reconstructed in the fhuE mutant and growth on desferrioxamine was confirmed in all three strains by a spotting assay (Fig 4A). Introduction of the wild type hmuR allele in the suppressor strains retained the suppressor phenotype (Fig 4A), confirming that the hmuR variants are gain-of-function alleles. Because the hmuR alleles recapitulated the original suppressor phenotype, we did not characterize the other mutations in those suppressors.

As with the EDDHA mutants, a single missense mutation within a ferric chelate transporter was sufficient to alter siderophore utilization, but the selection also picked up deletion mutants, showing surprising plasticity by the transporter. The hmuR suppressor alleles retained the ability to utilize heme as an iron source, although the deletion strains grew less well than the wild type or the fhuE parent strain (Fig. S5).

We measured 59Fe3+-desferrioxamine uptake activity of the fhuE suppressors, the fhuE parent strain and the wild type (Fig. 4B). Whereas uptake of 59Fe3+-desferrioxamine was severely diminished in the fhuE mutant, the three suppressor strains showed uptake activities similar to the wild type (Fig. 4B). Uptake rates of 59Fe3+-citrate, which does not require FhuE, were similar in all of the strains (Fig. 4B). Thus, transport of the Fe3+-desferrioxamine correlated with the growth phenotype of the suppressors and the fhuE parent strain.

The ferrous (Fe2+) iron transporter FeoB is required for utilization of both natural and synthetic siderophores

In well-described ferric siderophore transport systems such as enterobactin or ferrichrome uptake by E. coli, the ferric chelate is transported, intact, into the cytoplasm by selective components in the periplasm and cytoplasmic membrane as well as the outer membrane (Andrews et al., 2003, Noinaj et al., 2010, Faraldo-Gomez & Sansom, 2003). Therefore, it was surprising that mutation of an outer membrane transporter was sufficient to utilize the synthetic chelator EDDHA, which is structurally dissimilar to siderophores that B. japonicum can transport (Fig. S2). Thus, we investigated the possibility that ferric chelate iron uptake involves common components after it traverses the outer membrane.

We found previously that the ferrous (Fe2+) iron cytoplasmic membrane transporter FeoB is required for aerobic growth using ferric chloride as an iron source in B. japonicum (Sankari & O’Brian, 2016). Heme, however, is transported across the cytoplasmic membrane by an ABC transporter (Nienaber et al., 2001), hence heme utilization is independent of FeoB (Sankari & O’Brian, 2016) (Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 5. FeoB is essential for the utilization of natural and synthetic iron chelates.

(A) Growth on natural xenosiderophores. Serial dilution and spotting of cells grown in liquid GSY media with 100nM heme was performed on modified GSY media plates containing 10 μM heme (a), no added iron (b), 20 μM FeCl3 (c), 4 μM ferrichrome (d), 4 μM enterobactin (e) or 25 μM desferrioxamine (f). The fegA, entR and fhuE strains have defects in the ferricrhome, enterobactin and desferrioxamine transporter respectively. (B) Growth on EDDHA. Cells were grown in liquid GSY media with 100 nM heme, serially diluted and spotted on modified GSY media containing 10 μM heme (a), 100 μM EDDHA (b) or 100 μM EDDHA plus 10 μM heme (c). The entR(L272P) feoB strain has in-frame deletion in the feoB gene in the entR(L272P) background.

Here, we examined growth of an feoB strain on the siderophores ferrichrome, enterobactin or desferrioxamine and other iron sources. As observed previously, the feoB strain grew on heme, but not FeCl3 (Fig. 5A). The feoB mutant grew very poorly on the three siderophores tested, similar to growth of outer membrane transporter mutants on their cognate siderophore (Fig. 5A). We measured uptake of 59Fe3+-enterobactin, 59Fe3+-ferrichrome or 59Fe3+-desferrioxamine uptake in the feoB mutant, and found very little activity for any of those substrate compared with the wild type activity (Fig. 3A–C). Thus, the uptake data are in agreement with the growth phenotypes of the feoB strain (Fig. 5A). These findings indicate that the ferric chelates examined do not enter the cytoplasm intact via specific inner membrane transporters. Instead, the Fe3+ moiety is reduced to the ferrous form and dissociated from the chelate, followed by transport of Fe2+ across the cytoplasmic membrane by FeoB.

In addition to natural siderophores, deletion of feoB in the entR(L272P) mutant resulted in loss in the ability to grow on EDDHA (Fig. 5B). Thus, utilization of synthetic and naturally occurring ferric chelates requires the same cytoplasmic membrane transporter.

B. japonicum is more resistant than E. coli to the siderophore antibiotic albomycin

Albomycin is a naturally occurring antibiotic that contains a siderophore moiety similar to ferrichrome and an antibacterial portion that targets seryl-tRNA synthetases (Hartmann et al., 1979, Stefanska et al., 2000). In E. coli, albomycin is transported into cells by the ferrichrome transport system (Braun et al., 2009). This system delivers albomycin, intact, into the cytoplasm, and must be hydrolyzed there to exert its antibiotic activity (Braun et al., 1983, Hartmann et al., 1979).

The current findings indicate that ferrichrome enters the periplasm but not the cytoplasm in B. japonicum, and therefore we asked whether those cells are more resistant to albomycin compared to E. coli in a spotting assay (Fig. 6). As shown previously, there was very little growth of E. coli cells spotted onto plates containing albomycin (Fig. 6A). However, B. japonicum cells were much more resistant to the antibiotic (Fig. 6B). To determine whether this resistance was due to limited permeability of the B. japonicum cytoplasmic membrane for albomycin, we expressed the E. coli ferrichrome cytoplasmic membrane transporter genes fhuCDB from a plasmid in B. japonicum. The fhuCDB genes conferred albomycin sensitivity on those cells (Fig. 6B), indicating that B. japonicum normally (in the absence of fhuCDB) is limited in the ability to transport the siderophore antibiotic across the cytoplasmic membrane.

FIGURE 6. B. japonicum is resistant to albomycin compared with E. coli cells.

Cells were serially diluted, and 5 μl aliquots were spotted onto plates in the presence or absence of 2 μM albomycin. (A) E. coli cells. (B) B. japonicum strain 110 (Bj) or B. japonicum cells harboring the E. coli ferrichrome transport genes fhuCDB

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we show that B. japonicum possesses an iron acquisition system that can rapidly adapt to use new environmental sources. Features of this system include: (i) Outer membrane ferric siderophore transporters that can readily acquire productive gain-of-function mutations to utilize new iron chelates that are structurally dissimilar to the cognate ligand of the unmutated transporter. (ii) A cytoplasmic membrane transporter for Fe2+, not a ferric chelate, which does not need to be mutated to accommodate new environmental iron sources. (Fig. 7). A periplasmic ferric reductase with broad selectivity can be inferred from this as well. B. japonicum lives in soil communities, but does not synthesize its own siderophores, and therefore it is completely reliant on its environment to supply iron chelates. These chelates include siderophores made by other soil microbes. The features of iron acquisition described herein may facilitate rapid evolutionary adaptation to new communities. In this scenario, the inability to synthesize siderophores would provide selection pressure for gain-of-function mutants in the outer membrane transporter genes.

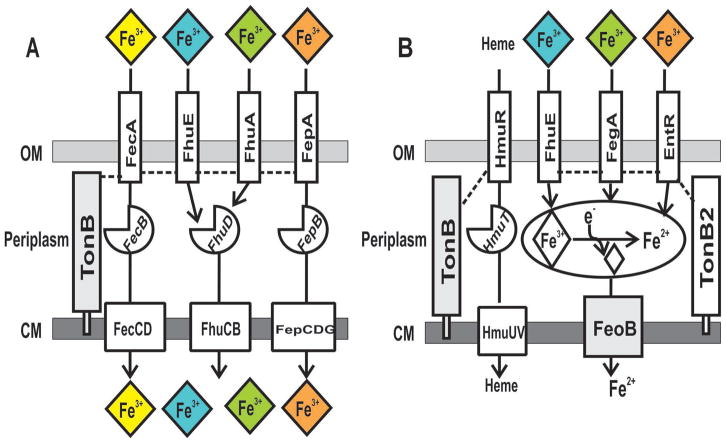

FIGURE 7. Comparison of ferric-chelate acquisition systems between E. coli and B. japonicum.

(A) In E.coli, outer membrane transporters FecA, FepA, FhuE, FhuA import Fe3+ chelates of citrate, enterobactin, desferrioxamine and ferrichrome, respectively. Translocation of ferric-chelates across the outer membrane is dependent on TonB (auxiliary proteins ExbB and ExbD are not shown). (B) In B. japonicum, intact heme is transported into the cytoplasm through the TonB-dependent outer membrane heme transporter, HmuR. The outer membrane xenosiderophore transporters FhuE, FegA, and EntR import Fe3+ chelates of desferrioxamine, ferrichrome and enterobactin, respectively. These transporters depend on TonB2. In the periplasm, Fe3+-siderophore is likely reduced to Fe2+ iron, potentially causing its release from the chelator. A single inner membrane transporter, FeoB, is responsible for importing Fe2+ iron into the cytoplasm.

Uncultivated microbial species are thought to dominate most natural ecosystems (Pace, 1997, Keller & Zengler, 2004). Analysis of uncultured bacterial isolates from a marine biofilm community reveals that siderophores provided by a microbial neighbor confer growth in culture on many of those studied (D’Onofrio et al., 2010). D’Onofrio et al (D’Onofrio et al., 2010) suggest that loss of siderophore synthetic capacity may ensure growth only in an environment populated by compatible neighbors. The current work raises the possibility that integration into this community involves productive mutations in outer membrane siderophore transporter genes.

Ligand binding sites of outer membrane transporters are formed from amino acid residues from the plug domain, the barrel wall and extracellular loops (Noinaj et al., 2010). An alignment of 12 tonB-dependent outer membrane transporters shows that these domains are conserved even though there is only modest amino acid sequence conservation (Noinaj et al., 2010). We aligned the B. japonicum transporters that were mutated with those analyses (Fig. S6). The three missense mutations within fegA or entR that conferred EDDHA utilization and the fhuE suppressor allele hmuR(W351R) are predicted to be in a loop or β-strands of the protein (Fig. S6). Interestingly, two hmuR alleles that suppress the fhuE phenotype encode proteins with deletions of 11 or 23 residues but still function as a transporter. Collectively, the mutants reveal that small sequence changes are sufficient to accommodate new iron chelates, but also that large changes can be tolerated.

The outer membrane transporter mutants that conferred growth on EDDHA or desferrioxamine retained the ability to use the iron chelate of the respective wild type transporter (Figs. S1, S3), suggesting a relaxed selectivity by the variants. However, the mutants were unable to use the synthetic chelator DTPA (Fig. 1) or pyoverdine (data not shown), and so they are not non-specific transporters. Nevertheless, lower selectivity raises the possibility that the transporter compromises the integrity of the outer membrane by allowing toxic compounds to traverse it. It is plausible that such compounds provide selective pressure for additional mutations that exclude them.

Outer membrane transporters deliver ferric siderophores, intact, into the periplasm, and FeoB transfers Fe2+ across the cytoplasmic membrane. Thus, iron must be reduced to the ferrous form and dissociate from the siderophore within the periplasm (Fig. 7). An EDDHA-utilizing mutants also requires FeoB (Fig. 5), suggesting that the reductase may not be highly specific since EDDHA is a synthetic chelator that is structurally dissimilar from natural siderophores (Fig. S2). The inner membrane-bound ferric reductase FrcB was previously identified in B. japonicum (Small & O’Brian, 2011), and therefore we examined growth of an frcB mutant on the siderophores enterobactin, ferrichrome or desferrioxamine (Fig. S7). The mutant grew well on the three compounds, and thus FrcB is unlikely to be the reductase needed for ferric chelate utilization. Identifying the reductase will be important to a full understanding of uptake.

Selective inner membrane transporters that carry siderophores into the cytoplasm have been described in numerous organisms, and they represent the predominant paradigm (Andrews et al., 2003, Noinaj et al., 2010). However, ferric iron reduction and dissociation from pyoverdine in the periplasm of P. aeruginosa has been described (Greenwald et al., 2007), but an feoB mutant retains pyoverdine-dependent growth (Marshall et al., 2009). Citrate-mediated iron uptake is diminished in a P. aeruginosa feoB mutant (Marshall et al., 2009), consistent with what we observed for iron chelates in the current study. Anaerobic growth of Bacteroides fragilis on Fe3+-ferrichrome is impaired in an feoAB mutant (Rocha & Krykunivsky, 2017)

Natural and synthetic siderophores are under study as potential antimicrobial therapies to address nosocomial infections or infections associated with iron overload diseases (Kontoghiorghes et al., 2010, Thompson et al., 2012, Ma et al., 2015). The possibility that some pathogenic bacteria may rapidly evolve to use these chelators as iron sources may need consideration in light of the current findings.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and chemicals

Desferrioxamine, ferrichrome, enterobactin and DTPA were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). EDDHA was obtained from the Complete Green Co., El Secundo, CA. Hemin was purchased from Frontier Scientific (Newark DE). Albomycin was obtained from EMC Microcollections (Tübingen, Germany).

Strains and media

B. japonicum USDA110 is the wild type strain used in this study. B. japonicum strains were routinely grown at 29 °C in glutamate-salts-yeast extract (GSY) medium as described previously (Frustaci et al., 1991). Where noted, modified GSY medium containing 0.5 g l−1 of yeast extract, instead of 1 g l−1, was used. The actual iron concentration of the unsupplemented medium was 0.3 μM, as determined with a PerkinElmer Life Sciences model 1100B atomic absorption spectrometer.

Selection of the EDDHA mutants and fhuE suppressors

108 cells of hmuP or fhuE strains were spread on modified GSY agar medium containing 100 μM EDDHA and 50 nM hemin or 25 μM desferrioxamine respectively. Plates were incubated for either 21 or 17 days at 29°C for EDDHA mutants or desferrioxamine suppressors to appear, respectively. The ability of the colonies to grow on EDDHA or desferrioxamine was verified by spotting assays. Genomic DNA was isolated from the wild type, the parent hmuP and fhuE strains and the selected colonies capable of growing on the desired iron source. High throughput sequencing with Illumina HiSeq2500 was used to identify the mutations. B. japonicum strain USDA110 (Accession no. NC_004463) (Kaneko et al., 2002) was used as the template genome. Mutations were confirmed using PCR and subsequent DNA sequencing of the PCR product.

Construction of strains and plasmids

Mutants with defective siderophore transporters in USDA110 background were constructed as described previously (Small et al., 2009). To generate single nucleotide transporter variants quick change mutagenesis (Stratagene) was performed on transporter genes cloned into pBluescriptSK+ resulting in pSKfegA(L497Q), pSKentR(L272P), pSKentR(T437P) and pSKhmuR(W351R). Inverse PCR was performed to construct deletions in hmuR gene to create pSKhmuR(Δ182-193) and pSKhmuR(Δ403-425). All the fragments were then cloned into pLO1. The clones pLO1fegA(L497Q), pLO1entR(L272P) and pLO1entR(T437P) were transferred to the wild type, whereas the mutated hmuR constructs in pLO1 were introduced into the fhuE strain, and selected for single or double recombinants as described (Panek & O’Brian, 2004). To generate tonB2 deletion strains, tonB2 gene with 500 bp of flanking DNA were cloned into pBluescript SK+ and inverse PCR was performed to make the in-frame deletion in the gene. The ΔtonB2 construct was then transferred to pLO1 and introduced into wild type or entR(L272P) strain by conjugation and double recombinants were selected. Deletion of feoB in entR(L272P) background was obtained by introducing pLO1feoB (Sankari & O’Brian, 2016) into the entR(L272P) mutant and selecting for double recombinants. All the mutants were confirmed by PCR and sequencing.

To produce a B. japonicum strain harboring E. coli fhuCDB, E. coli genomic DNA was amplified that included fhuCDB, and introduced into pRK290X that included the B. japonicum fegA promoter. pRK290X::fegAprom-fhuCDB was introduced into B. japonicum by triparental mating.

Spotting assay

Cells were grown in liquid GSY media or GSY media containing 100 nM heme to mid log phase. They were then washed, normalized to an O.D 540 nm of 0.3, serial diluted and 5 μl were spotted onto modified GSY agar medium with the indicated iron sources. For E. coli experiments, cells were grown to mid-log phase in LB medium and spotted on LB agar plates.

Analysis of RNA by quantitative real-time PCR

Transcript levels of selected genes were determined by qPCR, as described previously (Yang et al., 2006). Relative starting quantities of the mRNAs for the genes of interest and gapA were calculated from the corresponding standard curves. Quantity of the interested genes was normalized to the quantity of gapA for each respective condition. The data are expressed as average of triplicate samples ± SD.

Ferric iron uptake assay

Cells were grown to mid-log phase, centrifuged, washed twice, and resuspended in uptake buffer (0.2 M MOPS, and 2% (w/v) glycerol, pH 6.8) containing either 20 mM Citrate or 25 μM desferrioxamine to an OD540 of 0.4. 30 ml of cells were placed into a 125-ml flask and preincubated at 29°C with shaking. At time zero, 59FeCl3 was added to the cell suspension to a final concentration of 50 nM and iron uptake assay was performed as described previously (Hamza et al., 1998). Internalized 59Fe levels were normalized to protein levels in the cell and were expressed as average of three biological replicates ± SD.

Outer membrane transporter sequence alignment

The structure based sequence alignment of nine known crystal structures were performed using STRAP (Gille & Frommel, 2001) and analyzed using Jalview (Waterhouse et al., 2009) to obtain conservation scoring, similar to Noinaj et al (Noinaj et al., 2010). Sequences of the B. japonicum transporters FegA, EntR and HmuR were then realigned with the characterized transporters using Clustal omega (Sievers et al., 2011).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Hohle for providing the data for Figure S4. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 GM122947 to M.R.O’B.

References

- Alteri CJ, Hagan EC, Sivick KE, Smith SN, Mobley HLT. Mucosal immunization with iron receptor antigens protects against urinary tract infection. PLoS pathogens. 2009;5:e1000586. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amarelle V, Koziol U, Rosconi F, Noya F, O’Brian MR, Fabiano E. A new small regulatory protein, HmuP, modulates haemin acquisition in Sinorhizobium meliloti. Microbiology. 2010;156:1873–1882. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.037713-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews SC, Robinson AK, Rodriguez-Quinones F. Bacterial iron homeostasis. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003;27:215–237. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00055-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Günthner K, Hantke K, Zimmermann L. Intracellular activation of albomycin in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Journal of Bacteriology. 1983;156:308–315. doi: 10.1128/jb.156.1.308-315.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Pramanik A, Gwinner T, Köberle M, Bohn E. Sideromycins: tools and antibiotics. BioMetals. 2009;22:3. doi: 10.1007/s10534-008-9199-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumbaugh AR, Smith SN, Mobley HLT. Immunization with the yersiniabactin receptor, FyuA, protects against pyelonephritis in a murine model of urinary tract infection. Infection and Immunity. 2013;81:3309–3316. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00470-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chimento DP, Kadner RJ, Wiener MC. Comparative structural analysis of TonB-dependent outer membrane transporters: implications for the transport cycle. Proteins. 2005;59:240–251. doi: 10.1002/prot.20416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu BC, Garcia-Herrero A, Johanson TH, Krewulak KD, Lau CK, Peacock RS, Slavinskaya Z, Vogel HJ. Siderophore uptake in bacteria and the battle for iron with the host; a bird’s eye view. Biometals. 2010;23:601–611. doi: 10.1007/s10534-010-9361-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio A, Crawford JM, Stewart EJ, Witt K, Gavrish E, Epstein S, Clardy J, Lewis K. Siderophores from neighboring organisms promote the growth of uncultured bacteria. Chem Biol. 2010;17:254–264. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhaenens L, Szczebara F, Van Nieuwenhuyse S, Husson MO. Comparison of iron uptake in different Helicobacter species. Research in microbiology. 1999;150:475–481. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(99)00109-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escamilla-Hernandez R, O’Brian MR. HmuP is a co-activator of Irr-dependent expression of heme utilization genes in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:3137–3143. doi: 10.1128/JB.00071-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraldo-Gomez JD, Sansom MS. Acquisition of siderophores in gram-negative bacteria. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:105–116. doi: 10.1038/nrm1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frustaci JM, Sangwan I, O’Brian MR. Aerobic growth and respiration of a δ-aminolevulinic acid synthase (hemA) mutant of Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1145–1150. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.3.1145-1150.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gille C, Frommel C. STRAP: editor for STRuctural Alignments of Proteins. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:377–378. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.4.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald J, Hoegy F, Nader M, Journet L, Mislin GL, Graumann PL, Schalk IJ. Real time fluorescent resonance energy transfer visualization of ferric pyoverdine uptake in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. A role for ferrous iron. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:2987–2995. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609238200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu M, Imlay JA. Superoxide poisons mononuclear iron enzymes by causing mismetallation. Mol Microbiol. 2013;89:123–134. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamza I, Chauhan S, Hassett R, O’Brian MR. The bacterial Irr protein is required for coordination of heme biosynthesis with iron availability. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21669–21674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.34.21669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann A, Fiedler HP, Braun V. Uptake and conversion of the antibiotic albomycin by Escherichia coli K-12. Eur J Biochem. 1979;99:517–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1979.tb13283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko T, Nakamura Y, Sato S, Minamisawa K, Uchiumi T, Sasamoto S, Watanabe A, Idesawa K, Iriguchi M, Kawashima K, Kohara M, Matsumoto M, Shimpo S, Tsuruoka H, Wada T, Yamada M, Tabata S. Complete genomic sequence of nitrogen-fixing symbiotic bacterium Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA110. DNA Res. 2002;9:189–197. doi: 10.1093/dnares/9.6.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller M, Zengler K. Tapping into microbial diversity. Nature reviews. 2004;2:141–150. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontoghiorghes GJ, Kolnagou A, Skiada A, Petrikkos G. The role of iron and chelators on infections in iron overload and non iron loaded conditions: prospects for the design of new antimicrobial therapies. Hemoglobin. 2010;34:227–239. doi: 10.3109/03630269.2010.483662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krewulak KD, Vogel HJ. Structural biology of bacterial iron uptake. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:1781–1804. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeVier K, Guerinot ML. The Bradyrhizobium japonicum fegA gene encodes an iron-regulated outer membrane protein with similarity to hydroxamate-type siderophore receptors. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:7265–7275. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.24.7265-7275.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Gao Y, Maresso AW. Escherichia coli free radical-based killing mechanism driven by a unique combination of iron restriction and certain antibiotics. Journal of Bacteriology. 2015;197:3708–3719. doi: 10.1128/JB.00758-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall B, Stintzi A, Gilmour C, Meyer JM, Poole K. Citrate-mediated iron uptake in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: involvement of the citrate-inducible FecA receptor and the FeoB ferrous iron transporter. Microbiology. 2009;155:305–315. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.023531-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miethke M, Marahiel MA. Siderophore-based iron acquisition and pathogen control. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2007;71:413–451. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00012-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mike LA, Smith SN, Sumner CA, Eaton KA, Mobley HLT. Siderophore vaccine conjugates protect against uropathogenic Escherichia coli urinary tract infection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2016 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606324113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nienaber A, Hennecke H, Fischer HM. Discovery of a haem uptake system in the soil bacterium Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Mol Microbiol. 2001;41:787–800. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noinaj N, Guillier M, Barnard TJ, Buchanan SK. TonB-dependent transporters: regulation, structure, and function. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2010;64:43–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noya F, Arias A, Fabiano E. Heme compounds as iron sources for nonpathogenic Rhizobium bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3076–3078. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.3076-3078.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace NR. A molecular view of microbial diversity and the biosphere. Science. 1997;276:734–740. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5313.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panek HR, O’Brian MR. KatG is the primary detoxifier of hydrogen peroxide produced by aerobic metabolism in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:7874–7880. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.23.7874-7880.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne SM, Mey AR, Wyckoff EE. Vibrio iron transport: evolutionary adaptation to life in multiple environments. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2016;80:69–90. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00046-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plessner O, Klapatch T, Guerinot ML. Siderophore utilization by Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1688–1690. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.5.1688-1690.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postle K, Kadner RJ. Touch and go: tying TonB to transport. Mol Microbiol. 2003;49:869–882. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha ER, Krykunivsky AS. Anaerobic utilization of Fe(III)-xenosiderophores among Bacteroides species and the distinct assimilation of Fe(III)-ferrichrome by Bacteroides fragilis within the genus. MicrobiologyOpen. 2017:6. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde KH, Dyer DW. Mechanisms of iron acquisition by the human pathogens Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Front Biosci. 2003;8:d1186–1218. doi: 10.2741/1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankari S, O’Brian MR. The Bradyrhizobium japonicum ferrous iron transporter FeoAB is required for ferric iron utilization in free living aerobic cells and for symbiosis. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:15653–15662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.734129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schalk IJ, Guillon L. Fate of ferrisiderophores after import across bacterial outer membranes: different iron release strategies are observed in the cytoplasm or periplasm depending on the siderophore pathways. Amino Acids. 2013;44:1267–1277. doi: 10.1007/s00726-013-1468-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Soding J, Thompson JD, Higgins DG. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Molecular systems biology. 2011;7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small SK, O’Brian MR. The Bradyrhizobium japonicum frcB gene encodes a diheme ferric reductase. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:4088–4094. doi: 10.1128/JB.05064-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small SK, Puri S, Sangwan I, O’Brian MR. Positive control of ferric siderophore receptor gene expression by the Irr protein in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:1361–1368. doi: 10.1128/JB.01571-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanska AL, Fulston M, Houge-Frydrych C, Jones JJ, Warr SR. A potent seryl-tRNA synthetase inhibitor SB-217452 isolated from a Streptomyces species. J Antibiot. 2000;53:1346–1353. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.53.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MG, Corey BW, Si Y, Craft DW, Zurawski DV. Antibacterial activities of iron chelators against common nosocomial pathogens. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2012;56:5419–5421. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01197-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse AM, Procter JB, Martin DM, Clamp M, Barton GJ. Jalview Version 2--a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1189–1191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams P, Morton DJ, Towner KJ, Stevenson P, Griffiths E. Utilization of enterobactin and other exogenous iron sources by Haemophilus influenzae, H. parainfluenzae and H. paraphrophilus. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:2343–2350. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-12-2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Sangwan I, Lindemann A, Hauser F, Hennecke H, Fischer HM, O’Brian MR. Bradyrhizobium japonicum senses iron through the status of haem to regulate iron homeostasis and metabolism. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:427–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.