Abstract

Sensorimotor recovery after spinal cord injury (SCI) is of utmost importance to injured individuals and will rely on improved understanding of SCI pathology and recovery. Novel transgenic mouse lines facilitate discovery, but must be understood to be effective. The purpose of this study was to characterize the sensory and motor behavior of a common transgenic mouse line (Thy1-GFP-M) before and after SCI. Thy1-GFP-M positive (TG+) mice and their transgene negative littermates (TG-) were acquired from two sources (in-house colony, n = 32, Jackson Laboratories, n = 4). C57BL/6J wild-type (WT) mice (Jackson Laboratories, n = 10) were strain controls. Moderate-severe T9 contusion (SCI) or transection (TX) occurred in TG+ (SCI, n = 25, TX, n = 5), TG- (SCI, n = 5), and WT (SCI, n = 10) mice. To determine responsiveness to rehabilitation, a cohort of TG+ mice with SCI (n = 4) had flat treadmill (TM) training 42–49 days post-injury (dpi). To characterize recovery, we performed Basso Mouse Scale, Grid Walk, von Frey Hair, and Plantar Heat Testing before and out to day 42 post-SCI. Open field locomotion was significantly better in the Thy1 SCI groups (TG+ and TG-) compared with WT by 7 dpi (p < 0.01) and was maintained through 42 dpi (p < 0.01). These unexpected locomotor gains were not apparent during grid walking, indicating severe impairment of precise motor control. Thy1 derived mice were hypersensitive to mechanical stimuli at baseline (p < 0.05). After SCI, mechanical hyposensitivity emerged in Thy1 derived groups (p < 0.001), while thermal hyperalgesia occurred in all groups (p < 0.001). Importantly, consistent findings across TG+ and TG- groups suggest that the effects are mediated by the genetic background rather than transgene manipulation itself. Surprisingly, TM training restored mechanical and thermal sensation to baseline levels in TG+ mice with SCI. This behavioral profile and responsiveness to chronic training will be important to consider when choosing models to study the mechanisms underlying sensorimotor recovery after SCI.

Keywords: : locomotor function, rehabilitation, sensory function, spinal cord injury

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) results in significant sensory and motor dysfunction below the level of injury. While incomplete SCI typically includes some sensorimotor sparing and recovery of function, return to pre-injury levels is rare. Improving function after SCI leads to significant gains in quality of life and reductions in long-term healthcare utilization and costs.1,2 Individuals with SCI prioritize areas of functional recovery that depend on a controlled combination of sensory and motor activity.3 To maximize recovery of function, a greater understanding of the relationship between sensory function and motor recovery is needed. Injury models of SCI where sensory function diverges from motor recovery may be well suited to studying sensory and motor control.

A recent advance in the ability to examine structural plasticity occurred with the development of the Thy1 XFP mouse line in the laboratory of Joshua Sanes at Harvard University.4 Thy1 is a particularly interesting target for genetic manipulation. Also known as thymic antigen or CD90, Thy1 was identified originally as a cell surface antigen on thymocytes, mature T-cells, and neural tissues.5–7 In the central nervous system, however, Thy1 is also expressed on fibroblasts and some glial cells.8 The Thy1 gene has two alleles, Thy1.1 and Thy1.2, the latter being more commonly expressed in most mouse strains and associated with cytoskeletal elements such as actin.9 The Thy1 protein itself is a 25–37 kDa glycophosphatidylinositol-anchored protein found on the external leaf of the lipid bilayer10 and is involved in cellular adhesion, neurite outgrowth, tumor growth, migration, and cell death.11,12

To be incorporated effectively into useful injury models, transgenic mouse lines must be well characterized and understood. Even the genetic background must be considered, because strain differences can alter experimental outcomes.13–22 The Thy1 mouse line was generated on a mixed genetic background of predominately C57BL/6J, CBA, and another strain of unknown origin.23 Feng and associates4 describes this third strain as a non-Swiss Albino outbred strain, which was incorporated in several cases for three to five generations. The Thy1 XFP mouse line contains a modified regulatory region of the Thy1.2 gene allowing for the selective expression of fluorescent proteins on neuronal subsets throughout the central nervous system. By excluding exon 3 and the flanking introns upstream of the fluorescent protein sequence, the Thy1.2 gene was rendered “neuron specific,” resulting in a sparse, Golgi-like staining throughout the neuraxis. Multiple iterations were developed across four mutations of the green fluorescent protein (GFP; green, yellow, red, cyan) with each interestingly expressing the fluorescent protein in a slightly different pattern. These transgenic mice, especially the Thy1-GFP-M line, have been adopted and utilized in numerous studies to examine structural plasticity across a wide range of diseases, conditions, and interventions (Appendix 1).4,24–73

To date, few studies have evaluated the behavior of the Thy1-GFP-M mouse line,55,57,61,65,68,71,73 and no studies have examined sensory behavior or recovery after SCI (Appendix 1). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to characterize the sensory and motor behavior of Thy1-GFP-M mice before and after SCI. We examine responses to mechanical and thermal stimuli as well as both gross and fine motor performance. These findings will be important to consider when selecting models to examine structural plasticity after SCI.

Methods

Mice

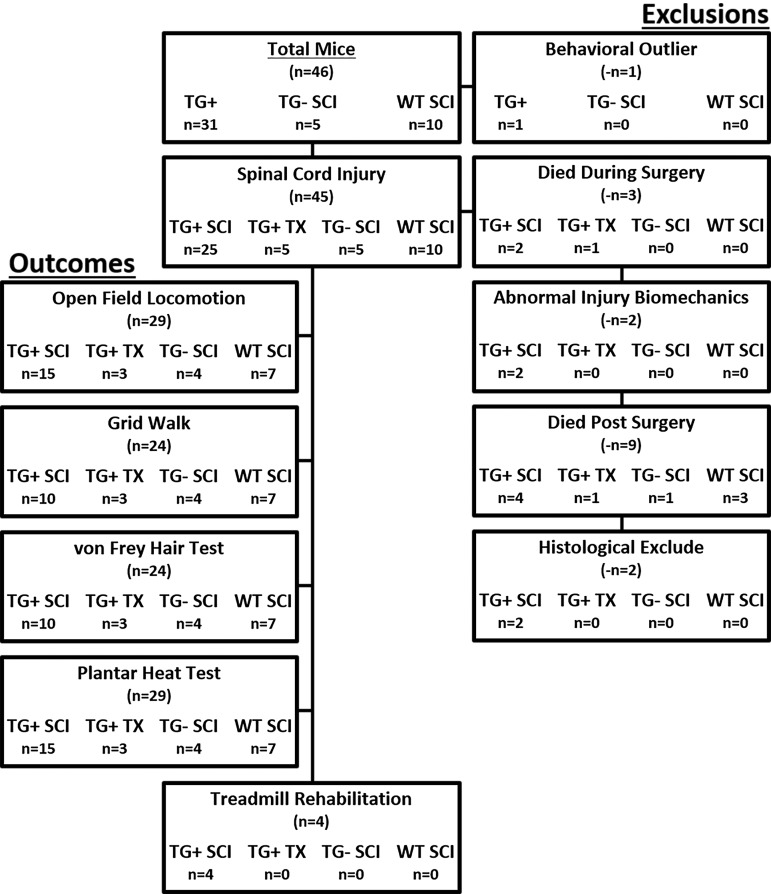

The disposition of all mice entered into the study, including use and reasons for exclusion, are described in Figure 1. Briefly, adult (2–4 months old), male and female Thy1-GFP-M positive (TG+) mice and their Thy1-GFP-M negative littermates (TG-) were acquired from two sources (in-house colony, n = 32 and Jackson Laboratories, n = 4). At baseline and after SCI, in-house and Jackson TG+ mice did not differ in size, injury severity, or behavioral performance (p > 0.05), except on the Von Frey Hair (VFH) Test (pre – in-house: 0.40 ± 0.06 g; Jackson: 0.83 ± 0.06 g; p < 0.05; post – in-house: 0.62 ± 0.08 g; Jackson: 2.05 ± 0.17g; p < 0.05). As such, in-house and Jackson-acquired TG+ mice were combined into a single TG+ group. C57BL/6J wild-type (WT) mice acquired from Jackson Laboratories (n = 10) served as strain controls. This strain is recommended as an “approximate control” because the Thy1-GFP-M mouse line has a mixed but predominately C57BL/6J background. Mice were housed three to five per cage and provided food and water ad libitum. All experiments were conducted in accordance with The Ohio State University Institutional Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee.

FIG. 1.

Animal enrollment and use. Flow diagram illustrates all mice included in the current studies. Animals included in behavioral outcomes testing are noted on the left. Timing and reason for exclusions are noted on the right. TG, transgenic; SCI, spinal cord injury; WT, wild type; TX, transection.

SCI

To determine the effect of axonal sparing on recovery in Thy1 derived mice, we randomized animals into contusion (SCI) or transection (TX) groups. To control for the effect of strain on recovery, WT mice received the same contusion injury. Because of minimal recovery reported in C57BL/6 mice with TX,15,74,75 a WT TX group was not included. There was no difference in weight between groups at the time of surgery (TG+ SCI = 21.0 ± 0.6 g; TG+ TX = 17.8 ± 0.6 g; TG- SCI = 18.5 ± 1.9 g; WT SCI = 18.4 ± 0.5 g; p > 0.05).

Spinal cord contusion was performed as described previously.76 In brief, mice were anesthetized with a ketamine (138 mg/kg)-xylazine (20 mg/kg) cocktail and given prophylactic antibiotic agents (gentocin, 1 mg/kg). Using aseptic techniques, removal of the T9 spinous process and lamina exposed the dura. After stabilizing the vertebral column, the Infinite Horizon (IH) device delivered 75 kdyn of force to induce a moderate-severe contusion injury. Force and displacement trends were similar to those established by Ghasemlou and colleagues77 (mean force: 76.7 ± 0.44 kdyn; mean displacement: 591.2 ± 19.76 μm).

For TX groups, the dura was opened at T9, and lidocaine was administered to the exposed spinal cord to suppress reflexes. The spinal cord was completely cut at T9 using irridectomy scissors, and a scalpel was used to cut along the spinal canal to ensure that all axons were cut. The incision was closed in layers, and 2 mL of sterile saline was administered subcutaneously (sq) to prevent dehydration. During recovery, mice received antibiotic agents (1 mg/kg gentocin, sq) and saline daily for five days and manual bladder expression twice per day until tissue harvest.74

Histology

Mice were deeply anesthetized with ketamine (207 mg/kg)-xylazine (30 mg/kg) and transcardially perfused with 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.2) at 42 or 49 days after SCI. Spinal cord segments from the epicenter were post-fixed for 1 h in 4% paraformaldehyde, rinsed overnight in 0.2M phosphate buffer (PB, pH 7.4), then cryoprotected in 30% sucrose before being embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound (Thermo Scientific) and frozen on dry ice.76,78,79 Epicenter blocks were sectioned transversely in their entirety at 20 μm on a Microm HM505E cryostat and every 10th section was stained for myelin using eriochrome cyanine. Eriochrome cyanine staining was differentiated using 5% iron alum and borax ferricyanide solutions.80

The lesion epicenter, identified as the section with the largest central core lesion and least amount of stained myelin, was quantified using stereological point counting (Stereoinvestigator; Microbrightfield). Using the Cavalieri method, a point grid was placed randomly over the epicenter section, and intersections over tissue were identified as spared white matter, spared gray matter, or lesioned tissue. Each intersection represented a point (p), and point counts for each section were converted to area estimates using the following formula: Estimated Area = (ΣP)*(a/p) where ΣP is the sum of the points for an individual mouse and a/p is the area of each point. The area of stained white matter at the epicenter was divided by total cross-sectional area to calculate a percentage of tissue sparing. The unstained tissue area was also divided by total cross-sectional area to determine percent lesion area.

Motor assessments

Open field locomotion

Locomotor recovery was assessed in the open field using the Basso Mouse Scale (BMS)15 before SCI, at one and seven days post-injury (dpi), and weekly thereafter. Two raters, blind to group assignment rated locomotor performance over 4 min considering joint movement, weight support, plantar stepping, coordination, paw position, trunk and tail control. Scores range from no hindlimb movement (0) to normal locomotor function (9).

Grid Walk

Fine motor control was evaluated in a subset of animals (TG+ SCI n = 10; TG+ TX n = 3; TG- SCI n = 4; WT SCI n = 7) by assessing precise paw placement during locomotion on a 2.54 cm square metal grid apparatus (41 × 28 × 36 mm). Mice were acclimated to the grid pre-operatively and then tested at naïve and 42 dpi. Performance was recorded with a digital camcorder (Handycam HDR SR11; Sony) and analyzed over five volitional passes. Success was determined by a weight-supported hindlimb step from rung to rung. The number of successful hindlimb steps are expressed relative to the number of forelimb steps and reported as percent success.

Sensory assessments

A male rater, blind to experimental groups, performed all sensory measures, which eliminated gender effects of the rater.81 Each sensory assessment was performed at a consistent time of day and did not occur on the same day as another sensory measure.

Mechanical sensitivity

Tactile sensitivity of the hindlimb was assessed in a subset of animals (TG+ SCI n = 10; TG+ TX n = 3; TG- SCI n = 4; WT SCI n = 7) using von Frey Hairs (Semmes Weinstein; Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL). Briefly, mice were placed under a small, opaque container on an elevated wire mesh to allow access to the plantar surface of the paws. Animals acclimated to the testing environment for 30 min before testing. Hindpaws were assessed using the up/down method, beginning with the 0.4 g filament applied to the plantar L5 dermatome.74,82,83 Each hindpaw received 10 consecutive trials. Additional trials were performed as needed to achieve a 50% withdrawal threshold, which was determined as the lowest force evoking withdrawal in at least half of the trials for that force. Mice with spinal cord transection were unable to achieve plantar placement, therefore were held gently to achieve plantar placement and assessed using the dorsal von Frey method described by Detloff and coworkers.84

Thermal sensitivity

Sensitivity to thermal stimuli was assessed according to the Hargreaves Method85 (Plantar Test Apparatus; Ugo Basile, Comerio, Italy). Mice (TG+ SCI n = 15; TG+ TX n = 3; TG- SCI n = 4; WT SCI n = 7) acclimated for 30 min before testing in individual clear plastic compartments (11 cm × 17 cm) with a glass floor. Infrared, radiant heat (25 watts) was applied to the plantar L5 dermatome through the glass until a withdrawal response occurred. A photocell on the heat source determined withdrawal and the duration (in seconds) of heat application (latency to withdraw). To prevent tissue damage, a 20 sec maximum application was set. Mice were tested randomly, and five trials were collected on each hindpaw. The longest and shortest latencies were dropped for each paw, before averaging the remaining latencies to yield a single withdrawal threshold for each mouse.

Literature review and synthesis

To place the behavior of the Thy1 mouse line into context with the SCI field, we performed a synthesis of the available literature examining sensory and motor behavior after SCI in mice. The PubMed literature search used combinations of the following search terms: spinal cord injury, spinal cord injuries (MeSH term), sensation, pain, neuropathic pain, hyperalgesia (MeSH term), and mice (MeSH term). Searches using only MeSH terms failed to yield results. To maximize generalizability, only studies in mice and only those using spinal cord contusion injury were included. All other SCI (TX, hemisection, etc.) and pain models (peripheral nerve injury, chronic constriction injury, etc.) were excluded. To be considered, studies were required to report open field locomotion (BMS or other open field locomotor scale) and either mechanical or thermal sensitivity. Only data reported as mechanical sensitivity in grams (g) or thermal sensitivity in latency (seconds) at each time point were included.

A total of 15 studies were included in the synthesis contributing a total of 16 SCI groups,74,82,86–98 because one study reported data from multiple injury severities.74 Of these studies, all 15 reported BMS or other open field locomotor scale (Tarlov Scale,99 n = 1), 12 reported mechanical sensitivity, and 13 reported thermal sensitivity. In studies in which pre-injury locomotor performance was not reported,88,89,91,97,98 the lowest reported pre-injury score from included studies was assigned (BMS = 8). Data from baseline and chronic SCI (determined as the latest time point examined in each respective study; range = 14 days to 6 months) for each outcome measure were compiled into group data. Percent change scores were calculated for each outcome measure averaged across studies. Average percent change for the compiled literature group was compared with TG+ SCI, TG- SCI, and WT SCI groups.

Rehabilitation paradigm

Treadmill training was performed in a subset of TG+ mice (TG+ TM; n = 4) from 42 to 49 days post-spinal cord contusion. Previously, this late training period did not improve locomotion in C57BL/6J mice, but sensory changes were not examined.76 Training consisted of eight consecutive days of quadrupedal stepping on a flat grade, custom-built treadmill (Columbus Instruments). Animals performed two, 10-min bouts of stepping separated by a 20-min rest break to deliver 1000+ steps during each 20-min session.100 Training speed was set initially at a comfortable pace (initial speed: 7.0 m/min) and increased progressively to the fastest speed that did not degrade stepping performance (max speed: 13.0 m/min). Manual assistance was provided as needed for trunk stability during locomotion.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using either one-way or two-way repeated measures analysis of variance with Tukey post hoc testing or a t test when appropriate. Relationships were determined using the Pearson correlation. Means and standard error of the mean (SEM) are reported throughout. Significance was set at p < 0.05 for all statistical tests.

Results

Thy1 mice have increased tissue sparing after SCI

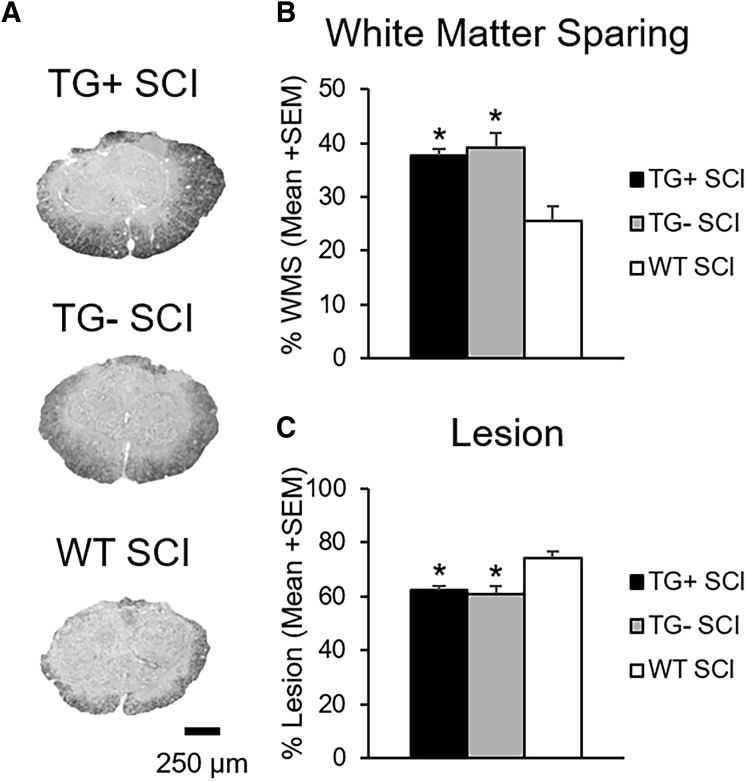

To begin characterizing recovery from SCI, we examined the extent of pathology at the lesion epicenter. Importantly, there was no difference between groups for injury force (TG+ = 76.9 ± 0.66 kdyn, TG- = 77.0 ± 1.1 kdyn, WT = 75.9 ± 0.6 kdyn; p > 0.05) or displacement (TG+ = 612.4 ± 32.0 μm, TG- = 511 ± 14.3 μm, WT = 591.7 ± 9.3 μm; p > 0.05) indicating that all groups received similar injuries. For both transgenic and WT groups, white matter sparing was localized to the peripheral edge of the lateral and ventral funiculi (Fig. 2A). Little sparing was noted in the dorsal columns where motor (corticospinal tract) and sensory (touch/proprioception) axons are located.

FIG. 2.

Transgenic (TG)+ and TG- mice have increased tissue sparing after spinal cord injury (SCI). Representative images of eriochrome cyanine staining at the injury epicenter show increased tissue sparing and decreased lesion size in Thy1-GFP-M mice (TG+, TG-) with SCI (A). Quantification of epicenter percent sparing and lesion size, respectively, is expressed as percent area (B, C; *p < 0.05; one-way analysis of variance). GFP, green fluorescent protein; WT, wild type; WMS, white matter sparing; SEM, standard error of the mean.

There was no difference in white matter sparing or lesion area between TG+ and TG- SCI animals (p > 0.05; Fig. 2B, C). WT SCI mice, however, had significantly less spared white matter and more lesion area than the Thy1-GFP-M mice (TG+, TG-) (p < 0.05). Epicenter white matter percent area ranged from 38% ± 1.46 for TG+ and 39% ± 2.85 for TG-, to 25% ± 2.58 for WT SCI controls (Fig. 2B).

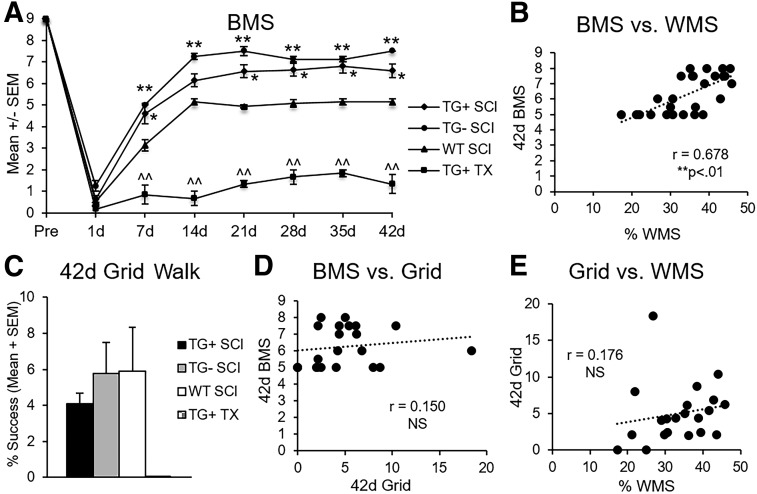

Thy1 mice have enhanced locomotor recovery but poor fine motor control after SCI

Using BMS for open field locomotion, we characterized recovery of the Thy1-GFP-M transgenic line after severe spinal cord contusion or TX (Fig. 3A). Regardless of transgene expression, Thy1-GFP-M mice (TG+, TG-) with contusion had greater locomotor recovery as early as seven dpi (p < 0.05) compared with WT mice (Fig. 3A). At one week post-contusion SCI, WT animals achieved plantar placement of the hindpaws (BMS = 3.14 ± 0.26), whereas Thy1-GFP-M mice (TG+, TG-) walked with uncoordinated steps (TG+ BMS = 4.6 ± 0.46, TG- BMS = 5.0 ± 0.0; Fig. 3A). The WT mice attained uncoordinated walking eventually but never exceeded it. Thy1-GFP-M mice (TG+, TG-) continued to improve significantly, regaining and maintaining coordinated locomotion (p < 0.05; Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

Transgenic (TG)+ and TG- mice have improved gross motor function but impaired precise motor control after spinal cord injury (SCI). TG+ and TG- SCI animals have significantly greater locomotor recovery as early as seven days post-injury (dpi) that persisted to chronic time points (42 days) (A; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs. wild type (WT) SCI; repeated measures analysis of variance [ANOVA]). All SCI performed better than transection (TX) mice after one dpi (A; ^^p < 0.01 vs. all groups; repeated measures ANOVA). In mice with SCI, open field performance was strongly correlated with epicenter sparing (B; *p < 0.01; Pearson r). Despite significantly greater overground locomotion, the TG+ and TG- groups did not exhibit better grid walking, suggesting that proprioception and precise motor control were markedly impaired (C; p > 0.05; one-way ANOVA). After contusion, fine motor performance was not correlated to either open field performance or sparing (D, E; p > 0.05; Pearson r). SEM, standard error of the mean; BMS, Basso Mouse Scale; WMS, white matter sparing.

As expected, TX in Thy1-GFP-M mice (TG+) resulted in isolated ankle movements only, which was significantly lower than all other groups at all points beyond one dpi (peak BMS = 1.83 ± 0.17; p < 0.01; Fig. 3A). Gross locomotor performance in the open field demonstrated a significant positive correlation to white matter sparing (r = 0.884, p < 0.01; data not shown). This relationship was strong enough that it was maintained across contusion animals even when TX animals were removed from the analysis (r = 0.678, p < 0.01; Fig. 3B).

To determine whether better open field performance translated to walking tasks requiring fine precision, we evaluated proprioception on a grid apparatus. Naïve animals perform grid locomotion using a 1:1 forelimb/hindlimb ratio where the forelimb contacts every other horizontal rung and is replaced by the ipsilateral hindlimb on the same rung. Before SCI, Thy1-GFP-M and WT animals demonstrate 98% accuracy (± 0.4%) of the hindlimb on the grid (range = 97.3–99.0%). After contusion, Thy1-GFP-M mice (TG+, TG-) had significant deficits and were equivalent to the WT controls, with 4–6% success (p > 0.05; Fig. 3C), despite significant between-group differences in open field locomotion. Spinal cord TX in TG+ mice eliminated hindlimb rung placement. Analysis of all animals showed that fine motor performance on the grid was significantly correlated to open field performance (r = 0.410, p < 0.05; data not shown) as well as white matter sparing (r = 0.426, p < 0.05, data not shown). These relationships, however, were not maintained between contusion groups when TX animals were removed from the analysis (r = 0.150 and r = 0.176, respectively, p > 0.05; Fig. 3D, E).

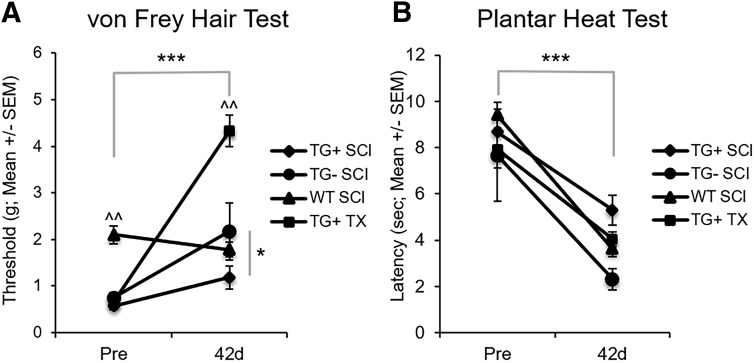

Thy1 mice have divergent sensory responses to thoracic SCI

Sensation plays an important role in locomotor recovery from SCI.101–105 Given that Thy1-GFP-M mice (TG+, TG-) had significantly greater open field locomotion without improved fine motor skills, we sought to better understand the sensory response to SCI in Thy1-GFP-M mice. Under normal conditions, Thy1-GFP-M mice (TG+, TG-) had mechanical hypersensitivity with significantly lower withdrawal thresholds to mechanical stimulation, regardless of transgene expression (TG+: 0.57 ± 0.08 g; TG-: 0.75 ± 0.1 g), compared with WT controls (2.1 ± 0.19 g, p < 0.05; Fig. 4A). After SCI, hyposensitivity to mechanical stimulation develops in Thy1-GFP-M mice in a severity-dependent manner (p < 0.001; Fig. 4A). Mice with cord transection require significantly more force to elicit hindlimb withdrawal than do mice with contusion SCI (p < 0.05). Conversely, hyposensitivity does not develop in WT animals, and they show a trend toward hypersensitivity in response to mechanical stimuli. The TG- group also required significantly more mechanical force than the TG+ group (p < 0.05). These results indicate that paresthesia rather than allodynia develops in Thy1-GFP-M mice after SCI.

FIG. 4.

Thy1 mice demonstrate divergent sensory recovery after spinal cord injury (SCI). Mechanical and thermal sensations were assessed using the von Frey Hair Test and Plantar Heat Test, respectively. Thy1 groups had hypersensitivity to mechanical stimuli before SCI that became paresthesia-like after SCI in a severity-dependent manner (A; ***p < 0.001 Main Effect of Time; ^^p < 0.01 vs. all groups; repeated measures analysis of variance [ANOVA]). In TG- mice, greater paresthesia developed than in TG+ mice (A; *p < 0.05; repeated measures ANOVA). All groups, regardless of background, green fluorescent protein expression, or injury severity become hypersensitive to thermal stimuli at 42 days post-injury (B; ***p < 0.001; repeated measures ANOVA). SEM, standard error of the mean; WT, wild type.

Alternatively, when we evaluated thermal sensation using infrared planter heat, we found that all animals exhibited similar thermal sensitivity at baseline (p > 0.05; Fig. 4B). After SCI, hyperalgesia develops in Thy1 (TG+, TG-) and WT mice (p < 0.001) regardless of transgene expression or background strain.

Thy1 sensory and motor behavior diverge from SCI literature

Given the Thy1-GFP-M line's gross motor improvements but poor fine motor and mechanical sensation after SCI, we compared them with typical behavioral responses in the field (Table 1). We performed a literature review and synthesis of mouse studies that investigated locomotion and either mechanical or thermal sensation after contusion SCI.74,82,86–92,94–98,106 Compared with the literature, Thy1-GFP-M mice (TG+, TG-) have significantly better gross locomotor performance as determined by decreased percent change from baseline, despite the severe injury model used in this study (TG+ p < 0.001, TG- p < 0.01 vs. literature; Table 1).

Table 1.

Sensorimotor Recovery after Spinal Cord Injury in Mice

| Open field locomotion | Mechanical sensitivity (g) | Thermal sensitivity (sec) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Mouse strain | Injury model (contusion) | Naive | SCI | % Change | Naive | SCI | % Change | Naive | SCI | % Change |

| Li et al. (2017) | C57BL/6 | T9, Moderate, 15 sec | 8^ | 4 | −50.0 | 0.45 g | 0.18 g | −60 | 12 sec | 5 sec | −58.3 |

| Matyas et al. (2017) | C57BL/6 | T9, Moderate, 60 kdyn | 8^ | 3.5 | −56.3 | 1 | 0.25 | −75 | - | - | - |

| Qian et al. (2017) | C57BL/6J | T9-T10, Moderate, 60 kdyn | 9 | 4 | −55.6 | 9.5 | 4.25 | −55 | 9.5 | 3.75 | −60.5 |

| Tateda et al. (2017) | C57BL/6 | T10, Moderate, 10g × 1.5 mm | 9 | 6 | −33.3 | 3 | 1.25 | −58 | 14 | 3 | −78.6 |

| Fandel et al. (2016) | B6.CB17-Prkdcscld/SzJ | T13, Moderate, 2g × 7.5 cm | 9 | 3 | −66.7 | 1 | 0.6 | −40 | 4.4 | 3.4 | −22.7 |

| Nees et al. (2016) | C57BL/6 NRj | T11, Mild, 50 kdyn | 9 | 6 | −33.3 | 1.4 | 0.4 | −71 | 9 | 6.5 | −27.8 |

| Wu et al. (2016) | C57BL/6 | T10, Moderate, 60 kdyn | 9 | 3 | −66.7 | 2 | 0.8 | −60 | - | - | - |

| Novrup et al. (2014) | C57BL/6 | T9, Moderate, 500 μm | 9 | 5.3 | −41.1 | - | - | - | 9 | 5.5 | −38.9 |

| Tep et al. (2013) | C57BL/6 | T9, Mild, 50 kdyn | 8^ | 5 | −37.5 | 3 | 3.5 | 17 | 2.3 | 1.9 | −17.4 |

| Murakami et al. (2013) | C57BL/6 | T10, Moderate, 60 kdyn | 9 | 5 | −44.4 | 7.5 | 5 | −33 | 4 | 2 | −50.0 |

| David et al. (2013) | C57BL/6 | T8, Severe, 70 kdyn | 8^ | 4 | −50.0 | - | - | - | 10.5 | 3.5 | −66.7 |

| Chen et al. (2012) | Cx30−/−Cx43fl/fl:hGFAP–Cre | T11, Mild, 3g × 6.75 mm | 8^ | 7 | −12.5 | - | - | - | 12 | 5 | −58.3 |

| Hoschouer et al. (2010) | C57BL/6 | T9, Moderate, 0.5 mm | 8 | 5 | −37.5 | 1.4 | 3 | 114 | 9.75 | 3.75 | −61.5 |

| T9, Severe, 0.7 mm | 8 | 3.5 | −56.3 | 1.4 | 1.1 | −21 | 9.75 | 3.5 | −64.1 | ||

| Meisner et al. (2010) | FVB GAD1:GFP | T11, Moderate, 50 kdyn | 5 | 2.4 | −52.0 | 1.4 | 0.5 | −64 | 14 | 6.5 | −53.6 |

| Hoschouer et al. (2009) | C57BL/6 × 129S7 | T9, Moderate, 0.5 mm | 9 | 5.5 | −38.9 | 2 | 2.5 | 25 | 9 | 5.2 | −42.2 |

| Average | 8.3 | 4.5 | −45.8 | 2.7 g | 1.8 g | −29.5 | 9.2 sec | 4.2 sec | −50.0 | ||

| SEM | 0.3 | 0.3 | 3.5 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 14.8 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 4.8 | ||

| Current study | WT (C57BL6) | T9, Severe, 75 kdyn | 9 | 5.1 | −43 | 2.1 g | 1.78 g | −15 | 9.4 sec | 3.6 sec | −61.7 |

| Thy1-GFP-M (TG+) | T9, Severe, 75 kdyn | 9 | 6.6 | −27*** | 0.57 | 1.19 | 109*** | 8.68 | 5.29 | −39.1 | |

| Thy1-GFP-M (TG-) | T9, Severe, 75 kdyn | 9 | 7.5 | −17*** | 0.75 | 2.18 | 182*** | 7.67 | 2.31 | −69.9 | |

Baseline, chronic spinal cord injury (SCI) and percent change data from the current contusion groups and 15 studies of mouse contusion SCI. Values with ^ symbol indicate assumed baseline values not reported in the study. Negative percent change indicates open field locomotor impairment, mechanical and thermal hypersensitivity at the chronic SCI time point. The average percent change of previous literature was compared with contusion groups from the current study. Wild type groups here performed consistent with the literature across all measures. Thy1 groups (TG+, TG-) had improved open field locomotion and opposite response to mechanical stimulation after SCI compared with the literature (***p < 0.001 vs. literature; one-way analysis of variance).

The majority of SCI groups from murine studies (13 of 16; Table 1) had increased mechanical sensitivity after SCI (baseline = 2.7 g, chronic SCI = 1.8 g; Table 1). Thy1 mice (TG+, TG-) with SCI demonstrate the opposite response, becoming hyposensitive to mechanical stimulation (p < 0.001 vs. literature). Conversely, all groups demonstrate hyperalgesia to thermal stimuli after SCI (p > 0.05 vs. literature; Table 1). The WT SCI group did not differ from the literature for open field performance, mechanical, or thermal sensation (p > 0.05 vs. literature; Table 1). These data confirm that the behavioral response of mice derived from the Thy1-GFP-M mouse line is truly unique.

Thy1-GFP-M mice are responsive to locomotor rehabilitation chronic after SCI

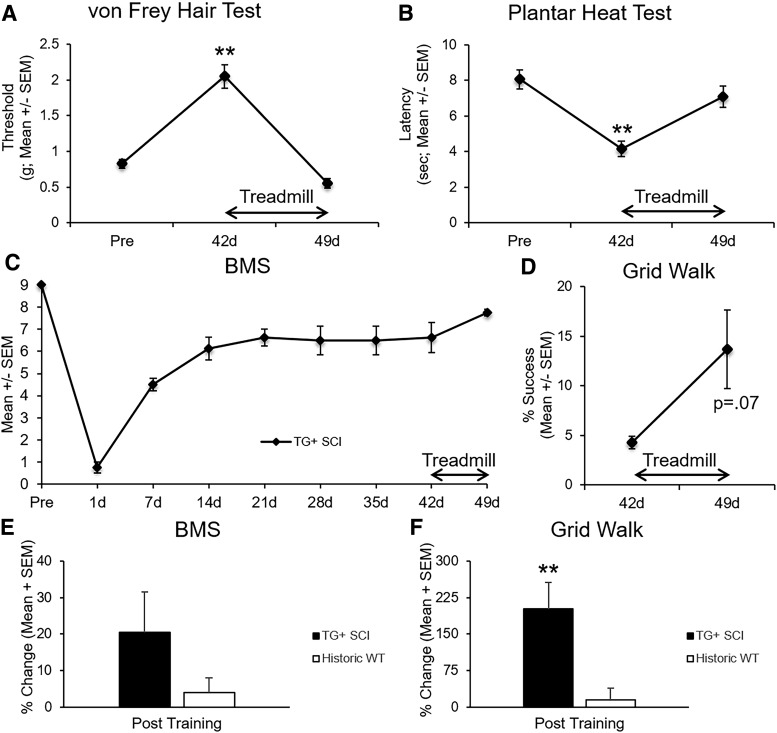

Because mice derived from the Thy1-GFP-M line demonstrate an unexpected, unique recovery profile after SCI, we tested sensorimotor responsiveness to late treadmill training (days 42–49) in a subset of TG+ mice, when little benefit occurs in WT mice.76 The brief, eight-session training produced significant changes in both mechanical and thermal sensitivity, restoring pre-injury tactile and pain levels (p < 0.05; Fig. 5A, B). Motor capacity showed less change. Gross overground locomotion and precision grid walking showed a trend toward improvement after training but did not reach significance (p = 0.13 and p = 0.07, respectively; Fig. 5C, D).

FIG. 5.

Late treadmill training normalizes sensation in transgenic (TG)+ mice. A subset of TG+ mice received eight consecutive days of treadmill training from 42–49 days post-injury. The eight-day rehabilitation paradigm restored mechanical and thermal sensitivity to pre-injury levels (A, B; **p < 0.01; repeated measures analysis of variance). Gross motor performance was less responsive to rehabilitation (C; p = 0.13; paired samples t test). Fine motor performance, however, showed a trend toward improvement after training (D; p = 0.07; paired samples t test). Compared with historic wild type (WT) mice that received chronic rehabilitation (Hansen and associates, 2013), TG+ mice showed a trend toward greater open field recovery (E; p = 0.17; independent samples t test) but significantly greater fine motor recovery (F; p < 0.01; independent samples t test). SEM, standard error of the mean; BMS, Basso Mouse Scale.

To better understand the degree of motor responsiveness to late-delivered rehabilitation in Thy1 derived mice, we compared the percent change of BMS and grid walk scores between TG+ and historic WT (C57BL/6J, n = 5) mice who received similar treadmill rehabilitation from 35–42 dpi.76 While there was a trend toward greater training-induced open field locomotor recovery in TG+ compared with historic WT mice (p = 0.17, Fig. 5E), TG+ mice demonstrated significantly more fine motor recovery during grid walk than historic WT animals in response to late treadmill training (p < 0.01, Fig. 5F).

Discussion

We describe the unexpected and unique sensorimotor behavior of Thy1-GFP-M derived mice before and after thoracic SCI. Interestingly, this mouse line displays both genetic and injury effects on sensorimotor behavior that warrant consideration. Under baseline conditions, mice derived from the Thy1-GFP-M line demonstrate hypersensitivity to touch when compared with C57BL6/J WT mice. It is possible that the current battery of measures did not detect baseline motor differences, although other reports utilizing mice derived from the Thy1-GFP-M and C57BL6/J indicate similar performance on rotarod.55,57,61,107 After SCI, Thy1 derived mice demonstrate remarkable gross motor capacity in the open field, ultimately achieving near normal levels. Interestingly, the exceptional gross motor performance did not translate to a precise motor task. Baseline tactile hypersensitivity gave way to mechanical paresthesia after SCI, while sensitivity to thermal stimuli increased. While all measures (sensory and motor) showed a tendency to improve with rehabilitation, sensory function was restored to baseline levels after the brief intervention period.

Of particular interest, the behavioral phenotype of Thy1 derived mice before and after SCI was consistent regardless of transgene expression, yet was strikingly different from the recommended approximate WT control. Thus, the combined background strains and not the transgene itself produce the unique behavioral phenotype likely rendering it stable over time. Having obtained Thy1-GFP-M mice from multiple sources further supports this observation and highlights the necessity of behavioral phenotyping for all new transgenic lines given the evidence that this study provides on the profound consequence of in-breeding and genetic drift.

While most of the behavioral effects observed in this study occurred to a similar extent in both TG+ and TG- mice after SCI or TX, this was not always the case. For instance, significantly greater hyposensitivity developed in TG- SCI mice than in TG+ SCI littermates, and TG+ TX mice had greater hyposensitivity still. A possible explanation for this finding could be the relatively small TG- group size. Otherwise, the finding of greater hyposensitivity in TG- mice suggests an unknown effect of GFP incorporation via the Thy1 promoter that blunts the development of paresthesia after SCI in TG+ mice. Future studies examining this phenomenon in established models of neuropathic pain, such as spared nerve injury or sural nerve ligation, are warranted to better understand this response.

The behavioral phenotype of Thy1 derived mice is accompanied by greater tissue sparing at the epicenter, but this sparing fails to fully account for the sensory and motor differences. Typically, after SCI, gross motor performance in the open field predicts fine motor ability,76,79,108–112 and both gross and fine motor performance are highly correlated with white matter sparing.15,76,79,112–115 In the Thy1 mouse line, gross and fine motor recovery were dissociated, and greater sparing was not correlated with fine motor recovery. The differential improvement of gross over fine motor control replicates the clinical progression of recovery in human SCI. Using this transgenic line to model human recovery provides an opportunity to test task-specific rehabilitation interventions directly targeting fine motor control.

Adaptive plasticity in regions remote from the injury site may play a role in gross but not fine motor control recovery. After incomplete SCI, neural networks undergo reorganization above and below the lesion.116–122 Damaged corticospinal axons form novel connections onto spared reticulospinal123,124 and rubrospinal125 neurons in the brainstem. In addition, axotomized supraspinal neurons form new intraspinal “bridges” onto cervical propriospinal neurons and bypass the lesion to compensate for lost function.116,119,120,123,126 Under normal circumstances, neuronal Thy1 interacts with astrocytes via integrin b3 to inhibit neurite outgrowth.127,128 It is possible that the genetic manipulation of the Thy1.2 gene, regardless of transgene expression, impacts the neuron/astrocyte interaction leading to enhanced neurite outgrowth and plasticity of pathways supporting gross locomotion. Indiscriminate, undirected sprouting above and/or below the lesion could support the development of gross but not fine motor performance. Further studies are required to determine whether the manipulation of the Thy1.2 gene alters the ability of Thy1 to effectively inhibit neurite outgrowth after SCI.

Interestingly, Thy1 derived mice demonstrated heightened sensitivity to mechanical stimulation at baseline compared with C57BL/6J mice. Importantly, this hypersensitivity did not appear to affect motor performance in the selected motor tests here. After SCI, below-level hyposensitivity to mechanical stimulation in a severity-dependent manner developed in Thy1 mice. Most mouse studies of sensation after SCI showed concurrent development of hyperalgesia and allodynia.82,87,90,94–98,106 At least three studies, however, have reported below-level mechanical hyposensitivity,74,86,91 all from laboratories at The Ohio State University despite using slightly different testing methods. Consistent with the mouse SCI literature, in this study, hyposensitivity after SCI did not develop in WT mice. In fact, WT mice became slightly hypersensitive, which is a more routine and expected outcome. Hyperalgesia developed to a similar degree in all mice after SCI, regardless of background, transgene expression, or injury severity.

Physical rehabilitation has shown the most promise for improving functional recovery after human SCI129–137 and will be an essential component of combinatorial therapies in the future.138,139 The optimal rehabilitation window to promote motor recovery is complex and largely unknown, however. Previous work from our laboratory and others shows that intervening too early after injury can exacerbate pathology and worsen functional recovery.76,140–143 Subacute rehabilitation, beginning four to 14 days after SCI, showed promise in preventing the development of neuropathic pain.94,144–147 Attempts to mitigate neuropathic pain or promote motor recovery in the chronic phase have failed, however.76,148

Consistent with previous data from our laboratory,15,76 WT mice with moderate-severe contusion SCI fail to recover coordinated locomotion. Conversely, 83% of Thy1 derived mice (TG+ = 80%, TG- = 100%) recovered at least some coordination by 42 dpi. This striking innate gross motor recovery drove our test of brief rehabilitation in Thy1 derived mice. Further, because TG+ and TG- mice exhibited consistent behavioral responses before and after SCI, we performed the brief bout of rehabilitation only in TG+ mice with chronic SCI. The longitudinal design eliminated confounds of heterogeneity and interanimal variability encountered when using cross-sectional data. Further, it allowed us to confirm a true recovery plateau over a long period and then deliver training.

Surprisingly, brief treadmill rehabilitation in the chronic phase of SCI restored baseline mechanical and thermal sensation in Thy1-GFP-M mice. The late responsiveness of sensation shown here provides a unique opportunity for future mechanistic studies in preventing or reducing allodynia. Further, while not statistically significant, motor function showed a striking trend of improvement after a four-week plateau that was greater than any recovery we have seen in response to chronic rehabilitation. The effects of rehabilitation on motor recovery observed here may be limited by the relatively small group size and single post-training analysis time point. Given these findings, it is prudent to perform a targeted examination of the effect of rehabilitation dose, intensity, frequency, and timing to promote motor recovery in Thy1 derived mice.

The importance of controlling for genetic background in neurotrauma research is well documented.16–22 In fact, at least three studies have directly investigated the effect of mouse strain on SCI pathology and recovery.13–15 Inman and associates13 identified increased lesion size and cavitation in mouse strains found to be sensitive to kainic acid-induced excitotoxicity (CD-1, FVB/N, 192T2 Sv/EMS, and C57BL/10) compared with kainic acid-resistant strains (C57BL/6 and BALB/c) after a T9 crush injury. Basso and colleagues15 were the first to show the impact of genetic factors on locomotor recovery after SCI. In this study, C57BL/10 along with BL10.PL and F1 mice demonstrated significantly better locomotor recovery than C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice after a moderate T9 contusion injury. Meanwhile, data from Kigerl and coworkers14 revealed decreased sparing, increased lesion length, and increased inflammation in C57BL/6 compared with BALB/c mice. Similar background-related findings have also been reported after SCI in rats.149,150 Taken together, these data reveal that genetic background not only affects SCI pathology and recovery, but that the observed effect may also be dependent on the type of injury.

That genetic background can have remarkable, widespread effects on behavior, pathophysiology, and recovery raises significant concerns regarding experiments in which Thy1 derived mice are incorporated for the sole purpose of anatomical study. Thy1 derived mice are often crossed with another transgenic animal of interest to focus on anatomical hypotheses. It is not uncommon, however, for behavioral assays to be performed exclusively on transgenic animals of interest and not Thy1-crossed mice.29,37,40,43,48,62 Mismatch of genetic background between groups could introduce significant variability, potentially confounding behavioral and anatomical data. Further, this approach limits the ability to associate behavioral findings with the anatomical changes observed in Thy1 crosses. In many of these cases, it is unclear whether the genetic background of transgenic mice used for experimental conditions and Thy1-crossed mice used for anatomy are consistent or similar. It will be important for studies using Thy1 derived mice as anatomical surrogates to carefully evaluate genetic background and behavior against that of other experimental animals included in the study to confirm that the responses are consistent.

Overall, our studies provide critical behavioral understanding of the Thy1-GFP-M mouse line and highlight the importance of controlling for the appropriate genetic background in studies of genetically engineered mouse strains. These findings warrant further consideration and enhance the utility of Thy1 derived mice in SCI research. Importantly, our findings highlight a unique behavioral phenotype that closely mimics the human condition. Similar to many patients with SCI, Thy1-GFP-M mice have excellent sensitivity to mechanical stimuli under normal conditions that gives way to paresthesia in a severity-dependent manner after SCI, whereas hyperalgesia develops regardless of injury severity. Further, Thy1 mice show rapid and exceptional gross motor recovery, yet fail to have fine motor skills develop. This pattern reveals an opportunity to target rehabilitation interventions at fine motor performance in severe SCI.

The fact that both motor and sensory measures appear responsive to brief rehabilitation supports the use of Thy1-GFP-M line as a model of human recovery. Improved understanding of the mechanisms underlying sensorimotor recovery is needed to improve functional recovery and quality of life for individuals with SCI. The Thy1-GFP-M line, with its distinctive sensorimotor behavioral profile and inherent fluorescence, allows a truly unique opportunity to study plasticity responses associated with sensorimotor recovery after SCI.

Appendix 1.

Publications Using the Thy1-GFP-M Mouse Line

| Article | Journal | Mouse line | Outcomes | Behavior | Behavioral outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feng G et al. (2000) | Neuron | Thy1-GFP | Immunohistochemistry | No | – |

| Wu JI et al. (2007) | Neuron | BAF53b−/− × Thy1-GFP-M | Neuron analysis | No | – |

| Carlisle HJ et al. (2008) | J Neurosci | Thy1-GFP-M × synGAP | Dendritic spine analysis | No | – |

| Mishra A et al. (2008) | Mol Cell Biol | Dasm-1+/− × Thy1-GFP-M | Dendrite/Spine analysis | No | – |

| Mazzoni F et al. (2008) | J Neurosci | Thy1-GFP-M rd10 × Thy1-GFP-M | Dendrite/Spine analysis | No | – |

| Stark KL et al. (2008) | Nat Genet | Thy1-GFP-M Dgcr8+/− × Thy1-GFP-M+/− | Dendritic spine analysis Behavior | Performed on non-GFP mouse lines | – |

| Vuksic M et al. (2008) | Hippocampus | Thy1-GFP-M | Neuronal analysis Electrophysiology | No | – |

| Belichenko NP et al. (2009) | Neurobiol Dis | Thy1-GFP-M Mecp2B × Thy1-GFP-M | Dendritic spine analysis | No | – |

| Chow DK et al. (2009) | Nature Neuroscience | αCamKII-Cre × Pten:loxP × Thy1-GFP-M | Dendritic spine analysis | No | – |

| Filosa A et al. (2009) | Nature Neuroscience | Tg181 (epha4) × Thy1-GFP-M | Dendritic spine analysis | No | – |

| Matter C et al. (2009) | Neuron | Thy1-GFP-M δ-catenin × Thy1-GFP-M | Dendrite/Spine analysis | No | – |

| Risher WC et al. (2009) | Glia | GFAP GFP × Thy1-GFP-M | Neuron/Dendrite analysis | No | – |

| Sakai Y et al. (2009) | Neurosci Res | Thy1-GFP-M COX2-KO × Thy1-GFP-M | Neuron/Dendrite analysis | No | – |

| Rust MB et al. (2010) | EMBO J | n‐cofflox/flox × CaMKII:Cre × Thy1-GFP-M | Dendritic spine analysis Behavior | Performed on Non-GFP mouse lines | – |

| Stritt C and Knoll B. (2010) | Mol Cell Biol | Srf−/− × Camk2a-iCre × Thy1-GFP-M | Neuron/Dendrite Analysis | No | – |

| Wilbrecht L et al. (2010) | J Neurosci | αCaMKII-T286A × Thy1-GFP-M | Dendritic Spine analysis Sensory deprivation | No | – |

| Carlisle HJ et al. (2011) | J Neurosci | Thy1-GFP-M+/− × Densin−/− Thy1-GFP-M+/− × Densin+/+ |

Dendritic spine analysis | Performed on non-GFP mouse lines | – |

| Kvajo M et al. (2011) | PNAS | Disc1 Tm1Kara × Thy1-GFP-M | Dendrite/Spine analysis | No | – |

| Landi S et al. (2011) | Sci Reports | MeCP2 KO × Thy1-GFP-M | Dendritic spine analysis | No | – |

| Lopez-Atalaya JP et al. (2011) | EMBO J |

Thy1-GFP-M Cbp+/− × Thy1-GFP-M |

Dendritic spine analysis Behavior |

Performed on non-GFP mouse lines | – |

| Matsuoka RL et al. (2011) | Neuron | Sema5A−/− × Thy1-GFP-M Sema5B−/− × Thy1-GFP-M |

Dendrite/Spine analysis | No | – |

| Paolicelli RC et al. (2011) | Science | Cx3cr1 GFP/KO × Thy1-GFP-M Cx3Cr1 GFP/GFP (KO/KO) × Thy1-GFP-M |

Electrophysiology Dendritic spine analysis |

No | – |

| Senturk A et al. (2011) | Nature | Reeler × EphrinB3 KO × Thy1-GFP-M Reeler × Nes-Cre × Thy1-GFP-M |

Neuron/Dendrite analysis | No | – |

| Allen NJ et al. (2012) | Nature | GPC4 KO × Thy1-GFP-M | Electrophysiology Immunohistochemistry |

No | – |

| Clement JP et al. (2012) | Cell | synGAP1 × Thy1-GFP-M | Electrophysiology Dendritic spine analysis Behavior |

Performed on non-GFP mouse lines | – |

| King AE et al. (2012) | Brain Res | G93A SOD1+ × Thy1-GFP-M G93A SOD1- × Thy1-GFP-M |

Axon analysis (spinal cord) | No | – |

| Li M et al. (2012) | Brain Res | Thy1-GFP-M | Dendrite/Spine analysis | No | – |

| Niisato E et al. (2012) | Dev Neurobiol | CRMP4−/− × Thy1-GFP-M | Neuron/Dendrite analysis | No | – |

| Wills ZP et al. (2012) | Neuron | NgR1−/− × Thy1-GFP-M NgR2−/− × Thy1-GFP-M NgR3−/− × Thy1-GFP-M |

Neuron/Dendrite analysis | No | – |

| Jiang M et al. (2013) | J Neurosci |

Thy1-GFP-M MeCP2-Tg1 × Thy1-GFP-M |

Dendritic spine analysis | No | – |

| Laperchia C et al. (2013) | PLoS One | Thy1-GFP-M | Two-photon Microscopy | No | – |

| Murmu RP et al. (2013) | J Neurosci | R6/2−/− × Thy1-GFP-M+/− R6/2+/− × Thy1-GFP-M+/− |

Dendritic spine analysis Behavior |

Yes | Rotarod |

| Wang IT et al. (2013) | Neurobiol Dis | MeCP2 Mutants × Thy1-GFP-M | Neuron/Dendrite analysis | No | – |

| Castello NA et al. (2014) | PLoS One | CaM−/− × Tet-Dta+/+ × Thy1-GFP-M+/+ CaM+/− × Tet-Dta+/+ × Thy1-GFP-M+/+ |

Dendritic spine analysis Behavior |

Yes | Rotarod Elevated Plus Maze Water Maze |

| Cooper MA and Koleske AJ (2014) | J Comp Neurol | erbb4flox/flox × Thy1-GFP-M | Dendritic spine analysis | No | – |

| Kallop DY et al. (2014) | J Neurosci | PS2APP-Tg × DR6−/− × Thy1-GFP-M | Dendritic spine analysis | No | – |

| Mishra A et al. (2014) | J Neurosci | IgSF9+/− × Thy1-GFP-M IgSF9+/− × GAD65 × Thy1-GFP-M |

Electrophysiology Dendritic spine analysis |

No | – |

| Park JI et al. (2014) | PLoS One | NgR−/− × Thy1-GFP-M NgR1flox/flox × Thy1-GFP-M Thy1-GFP-M |

Dendritic spine analyses Axon analyses Behavior |

Yes | Rotarod Tone-associated Fear |

| Pleiser S et al. (2014) | Eur J Cell Biol | spir-1 gt/+ × Thy1-GFP-M | Dendritic spine analysis Behavior |

Performed on Non-GFP mouse lines | – |

| Renier N et al. (2014) | Cell | Thy1-GFP-M | Tissue Clearing Whole Organ Imaging Methods |

No | – |

| Winkle CC et al. (2014) | J Cell Biol | TRIM9+/+ × Thy1 EGPF/M TRIM9−/− × Thy1-GFP-M |

Neuron/Dendrite analysis | No | – |

| Zhan Y et al. (2014) | Nature Neuroscience |

Thy1-GFP-M Cx3cr1 KO × Thy1-GFP-M |

Electrophysiology Behavior |

Yes | Novel Object Grooming Test Social Preference Test |

| Lauterborn JC et al. (2015) | Cereb Cortex |

Thy1-GFP-M Fmr1 KO × Thy1-GFP-M |

Dendrite/Spine analysis | No | – |

| Murmu RP et al. (2015) | J Neurosci | R6/2−/− × Thy1-GFP-M+/− R6/2+/− × Thy1-GFP-M+/− |

Dendritic spine analysis Sensory deprivation |

No | – |

| Zhan Y. (2015) | Neuroscience |

Thy1-GFP-M Cx3cr1 KO × Thy1-GFP-M |

Electrophysiology Behavior |

Yes | Open Field Social Interaction Test Light Dark Test |

| Zhang H et al. (2015) | J Neurosci | APP-KI × Thy1-GFP-M | Dendritic spine analysis | No | – |

| Sajo M et al. (2016) | J Neurosci |

Thy1-GFP-M Lynx1-KO × Thy1-GFP-M |

Dendritic spine analysis | No | – |

| Zou C et al. (2016) | EMBO J |

Thy1-GFP-M APP-KO × Thy1-GFP-M |

Dendritic spine analysis Behavior |

Yes | Novel Object |

| Guo C et al. (2017) | Sci Reports | Thy1-GFP-M | Neuron/Dendrite analysis | No | – |

| Lerch JK et al. (2017) | eNeuro |

Thy1-GFP-M C57BL/6 |

Axon Regeneration | No | – |

| Wohleb ES et al. (2017) | Biol Psychiatry |

Thy1-GFP-M C57BL/6 |

Dendritic spine analysis Behavior | Yes | Open Field Test Forced Swim Test Sucrose Consumption Test Novelty-suppressed Feeding |

Acknowledgments

This work is funded by 1F31NS096921-01A1 (TDF), 1RO1NS074882-01A1 (DMB), P30- NS04758 (CBSCR), a Florence P. Kendall Post-Professional Doctoral Scholarship (TDF) and Promotion of Doctoral Studies – Level I & II Scholarships from the Foundation for Physical Therapy (TDF). The authors would like to thank Drs. Karl Obrietan and Phillip Popovich for generously providing the Thy1-GFP-M mice used in this study.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.DeVivo M. and Farris V. (2011). Causes and costs of unplanned hospitalizations among persons with spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj. Rehabil. 16, 53–61 [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeJong G., Tian W., Hsieh C.H., Junn C., Karam C., Ballard P.H., Smout R.J., Horn S.D., Zanca J.M., Heinemann A.W., Hammond F.M., and Backus D. (2013). Rehospitalization in the first year of traumatic spinal cord injury after discharge from medical rehabilitation. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 94, Suppl, S87–S97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson K.D. (2004). Targeting recovery: priorities of the spinal cord-injured population. J. Neurotrauma 21, 1371–1383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng G., Mellor R.H., Bernstein M., Keller-Peck C., Nguyen Q.T., Wallace M., Nerbonne J.M., Lichtman J.W. and Sanes J.R. (2000). Imaging neuronal subsets in transgenic mice expressing multiple spectral variants of GFP. Neuron 28, 41–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reif A.E. and Allen J.M. (1964). Immunological distinction of AKR thymocytes. Nature 203, 886–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reif A.E. and Allen J.M. (1964). The AKR thymic antigen and its distribution in leukemias and nervous tissues. J. Exp. Med. 120, 413–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reif A.E. and Allen J.M. (1966). Mouse thymic iso-antigens. Nature 209, 521–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raff M.C., Fields K.L., Hakomori S.I., Mirsky R., Pruss R.M., and Winter J. (1979). Cell-type-specific markers for distinguishing and studying neurons and the major classes of glial cells in culture. Brain Res. 174, 283–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dales S., Fujinami R.S., and Oldstone M.B. (1983). Serologic relatedness between Thy-1.2 and actin revealed by monoclonal antibody. J. Immunol. 131, 1332–1338 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang H.C., Seki T., Moriuchi T. and Silver J. (1985). Isolation and characterization of mouse Thy-1 genomic clones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 82, 3819–3823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rege T.A. and Hagood J.S. (2006). Thy-1 as a regulator of cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions in axon regeneration, apoptosis, adhesion, migration, cancer, and fibrosis. FASEB J. 20, 1045–1054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rege T.A. and Hagood J.S. (2006). Thy-1, a versatile modulator of signaling affecting cellular adhesion, proliferation, survival, and cytokine/growth factor responses. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1763, 991–999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inman D., Guth L., and Steward O. (2002). Genetic influences on secondary degeneration and wound healing following spinal cord injury in various strains of mice. J. Comp. Neuro.l 451, 225–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kigerl K.A., McGaughy V.M., and Popovich P.G. (2006). Comparative analysis of lesion development and intraspinal inflammation in four strains of mice following spinal contusion injury. J. Comp. Neurol. 494, 578–594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Basso D.M., Fisher L.C., Anderson A.J., Jakeman L.B., McTigue D.M., and Popovich P.G. (2006). Basso Mouse Scale for locomotion detects differences in recovery after spinal cord injury in five common mouse strains. J. Neurotrauma 23, 635–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fox G.B., LeVasseur R.A., and Faden A.I. (1999). Behavioral responses of C57BL/6, FVB/N, and 129/SvEMS mouse strains to traumatic brain injury: implications for gene targeting approaches to neurotrauma. J. Neurotrauma 16, 377–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan A.A., Quigley A., Smith D.C., and Hoane M.R. (2009). Strain differences in response to traumatic brain injury in Long-Evans compared to Sprague-Dawley rats. J. Neurotrauma 26, 539–548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reid W.M., Rolfe A., Register D., Levasseur J.E., Churn S.B., and Sun D. (2010). Strain-related differences after experimental traumatic brain injury in rats. J. Neurotrauma 27, 1243–1253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang G., Kitagawa K., Matsushita K., Mabuchi T., Yagita Y., Yanagihara T., and Matsumoto M. (1997). C57BL/6 strain is most susceptible to cerebral ischemia following bilateral common carotid occlusion among seven mouse strains; selective neuronal death in the murine transient forebrain ischemia. Brain Res. 752, 209–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barone F.C., Knudsen D.J., Nelson A.H., Feuerstein G.Z., and Willette R.N. (1993). Mouse strain differences in susceptibility to cerebral ischemia are related to cerebral vascular anatomy. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 13, 683–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Connolly E.S., Jr., Winfree C.J., Stern D.M., Solomon R.A., and Pinsky D.J. (1996). Procedural and strain-related variables significantly affect outcome in a murine model of focal cerebral ischemia. Neurosurgery 38, 523–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujii M., Hara H., Meng W., Vonsattel J.P., Huang Z., and Moskowitz M.A. (1997). Strain-related differences in susceptibility to transient forebrain ischemia in SV-129 and C57black/6 mice. Stroke 28, 1805–1810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The Jackson Laboratory (2017). https://www.jax.org/strain/007788 Description of Tg(Thy1-EGFP)MJrs/J. Stock No: 007788

- 24.Lerch J.K., Alexander J.K., Madalena K.M., Motti D., Quach T., Dhamija A., Zha A., Gensel J.C., Webster Marketon J., Lemmon V.P., Bixby J.L., and Popovich P.G. (2017). Stress increases peripheral axon growth and regeneration through glucocorticoid receptor-dependent transcriptional programs. eNeuro 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu J.I., Lessard J., Olave I.A., Qiu Z., Ghosh A., Graef I.A., and Crabtree G.R. (2007). Regulation of dendritic development by neuron-specific chromatin remodeling complexes. Neuron 56, 94–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carlisle H.J., Manzerra P., Marcora E., and Kennedy M.B. (2008). SynGAP regulates steady-state and activity-dependent phosphorylation of cofilin. J. Neurosci. 28, 13673–13683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mishra A., Knerr B., Paixao S., Kramer E.R., and Klein R. (2008). The protein dendrite arborization and synapse maturation 1 (Dasm-1) is dispensable for dendrite arborization. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 2782–2791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mazzoni F., Novelli E., and Strettoi E. (2008). Retinal ganglion cells survive and maintain normal dendritic morphology in a mouse model of inherited photoreceptor degeneration. J. Neurosci. 28, 14282–14292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stark K.L., Xu B., Bagchi A., Lai W.S., Liu H., Hsu R., Wan X., Pavlidis P., Mills A.A., Karayiorgou M., and Gogos J.A. (2008). Altered brain microRNA biogenesis contributes to phenotypic deficits in a 22q11-deletion mouse model. Nat. Genet. 40, 751–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vuksic M., Del Turco D., Bas Orth C., Burbach G.J., Feng G., Muller C.M., Schwarzacher S.W., and Deller T. (2008). 3D-reconstruction and functional properties of GFP-positive and GFP-negative granule cells in the fascia dentata of the Thy1-GFP mouse. Hippocampus 18, 364–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Belichenko N.P., Belichenko P.V., and Mobley W.C. (2009). Evidence for both neuronal cell autonomous and nonautonomous effects of methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 in the cerebral cortex of female mice with Mecp2 mutation. Neurobiol. Dis. 34, 71–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chow D.K., Groszer M., Pribadi M., Machniki M., Carmichael S.T., Liu X., and Trachtenberg J.T. (2009). Laminar and compartmental regulation of dendritic growth in mature cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 116–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Filosa A., Paixao S., Honsek S.D., Carmona M.A., Becker L., Feddersen B., Gaitanos L., Rudhard Y., Schoepfer R., Klopstock T., Kullander K., Rose C.R., Pasquale E.B., and Klein R. (2009). Neuron-glia communication via EphA4/ephrin-A3 modulates LTP through glial glutamate transport. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 1285–1292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matter C., Pribadi M., Liu X., and Trachtenberg J.T. (2009). Delta-catenin is required for the maintenance of neural structure and function in mature cortex in vivo. Neuron 64, 320–327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Risher W.C., Andrew R.D., and Kirov S.A. (2009). Real-time passive volume responses of astrocytes to acute osmotic and ischemic stress in cortical slices and in vivo revealed by two-photon microscopy. Glia 57, 207–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sakai Y., Tanaka T., Seki M., Okuyama S., Fukuchi T., Yamagata K., Takei N., Nawa H., and Abe H. (2009). Cyclooxygenase-2 plays a critical role in retinal ganglion cell death after transient ischemia: real-time monitoring of RGC survival using Thy-1-EGFP transgenic mice. Neurosci. Res. 65, 319–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rust M.B., Gurniak C.B., Renner M., Vara H., Morando L., Gorlich A., Sassoe-Pognetto M., Banchaabouchi M.A., Giustetto M., Triller A., Choquet D., and Witke W. (2010). Learning, AMPA receptor mobility and synaptic plasticity depend on n-cofilin-mediated actin dynamics. EMBO J. 29, 1889–1902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stritt C. and Knoll B. (2010). Serum response factor regulates hippocampal lamination and dendrite development and is connected with reelin signaling. Mol. Cell Biol. 30, 1828–1837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilbrecht L., Holtmaat A., Wright N., Fox K., and Svoboda K. (2010). Structural plasticity underlies experience-dependent functional plasticity of cortical circuits. J. Neurosci. 30, 4927–4932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carlisle H.J., Luong T.N., Medina-Marino A., Schenker L., Khorosheva E., Indersmitten T., Gunapala K.M., Steele A.D., O'Dell T.J., Patterson P.H., and Kennedy M.B. (2011). Deletion of densin-180 results in abnormal behaviors associated with mental illness and reduces mGluR5 and DISC1 in the postsynaptic density fraction. J. Neurosci. 31, 16194–16207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kvajo M., McKellar H., Drew L.J., Lepagnol-Bestel A.M., Xiao L., Levy R.J., Blazeski R., Arguello P.A., Lacefield C.O., Mason C.A., Simonneau M., O'Donnell J.M., MacDermott A.B., Karayiorgou M., and Gogos J.A. (2011). Altered axonal targeting and short-term plasticity in the hippocampus of Disc1 mutant mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, E1349–E1358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Landi S., Putignano E., Boggio E.M., Giustetto M., Pizzorusso T., and Ratto G.M. (2011). The short-time structural plasticity of dendritic spines is altered in a model of Rett syndrome. Sci. Rep. 1, 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lopez-Atalaya J.P., Ciccarelli A., Viosca J., Valor L.M., Jimenez-Minchan M., Canals S., Giustetto M., and Barco A. (2011). CBP is required for environmental enrichment-induced neurogenesis and cognitive enhancement. EMBO J. 30, 4287–4298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matsuoka R.L., Chivatakarn O., Badea T.C., Samuels I.S., Cahill H., Katayama K., Kumar S.R., Suto F., Chedotal A., Peachey N.S., Nathans J., Yoshida Y., Giger R.J., and Kolodkin A.L. (2011). Class 5 transmembrane semaphorins control selective Mammalian retinal lamination and function. Neuron 71, 460–473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paolicelli R.C., Bolasco G., Pagani F., Maggi L., Scianni M., Panzanelli P., Giustetto M., Ferreira T.A., Guiducci E., Dumas L., Ragozzino D., and Gross C.T. (2011). Synaptic pruning by microglia is necessary for normal brain development. Science 333, 1456–1458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Senturk A., Pfennig S., Weiss A., Burk K., and Acker-Palmer A. (2011). Ephrin Bs are essential components of the Reelin pathway to regulate neuronal migration. Nature 472, 356–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Allen N.J., Bennett M.L., Foo L.C., Wang G.X., Chakraborty C., Smith S.J., and Barres B.A. (2012). Astrocyte glypicans 4 and 6 promote formation of excitatory synapses via GluA1 AMPA receptors. Nature 486, 410–414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clement J.P., Aceti M., Creson T.K., Ozkan E.D., Shi Y., Reish N.J., Almonte A.G., Miller B.H., Wiltgen B.J., Miller C.A., Xu X., and Rumbaugh G. (2012). Pathogenic SYNGAP1 mutations impair cognitive development by disrupting maturation of dendritic spine synapses. Cell 151, 709–723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.King A.E., Blizzard C.A., Southam K.A., Vickers J.C., and Dickson T.C. (2012). Degeneration of axons in spinal white matter in G93A mSOD1 mouse characterized by NFL and alpha-internexin immunoreactivity. Brain Res. 1465, 90–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li M., Masugi-Tokita M., Takanami K., Yamada S., and Kawata M. (2012). Testosterone has sublayer-specific effects on dendritic spine maturation mediated by BDNF and PSD-95 in pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus CA1 area. Brain Res. 1484, 76–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Niisato E., Nagai J., Yamashita N., Abe T., Kiyonari H., Goshima Y., and Ohshima T. (2012). CRMP4 suppresses apical dendrite bifurcation of CA1 pyramidal neurons in the mouse hippocampus. Dev. Neurobiol. 72, 1447–1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wills Z.P., Mandel-Brehm C., Mardinly A.R., McCord A.E., Giger R.J. and Greenberg M.E. (2012). The nogo receptor family restricts synapse number in the developing hippocampus. Neuron 73, 466–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jiang M., Ash R.T., Baker S.A., Suter B., Ferguson A., Park J., Rudy J., Torsky S.P., Chao H.T., Zoghbi H.Y., and Smirnakis S.M. (2013). Dendritic arborization and spine dynamics are abnormal in the mouse model of MECP2 duplication syndrome. J. Neurosci. 33, 19518–19533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Laperchia C., Allegra Mascaro A.L., Sacconi L., Andrioli A., Matte A., De Franceschi L., Grassi-Zucconi G., Bentivoglio M., Buffelli M., and Pavone F.S. (2013). Two-photon microscopy imaging of thy1GFP-M transgenic mice: a novel animal model to investigate brain dendritic cell subsets in vivo. PLoS One 8, e56144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murmu R.P., Li W., Holtmaat A., and Li J.Y. (2013). Dendritic spine instability leads to progressive neocortical spine loss in a mouse model of Huntington's disease. J. Neurosci. 33, 12997–13009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang I.T., Reyes A.R., and Zhou Z. (2013). Neuronal morphology in MeCP2 mouse models is intrinsically variable and depends on age, cell type, and Mecp2 mutation. Neurobiol. Dis. 58, 3–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Castello N.A., Nguyen M.H., Tran J.D., Cheng D., Green K.N., and LaFerla F.M. (2014). 7,8-Dihydroxyflavone, a small molecule TrkB agonist, improves spatial memory and increases thin spine density in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease-like neuronal loss. PLoS One 9, e91453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cooper M.A. and Koleske A.J. (2014). Ablation of ErbB4 from excitatory neurons leads to reduced dendritic spine density in mouse prefrontal cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 522, 3351–3362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kallop D.Y., Meilandt W.J., Gogineni A., Easley-Neal C., Wu T., Jubb A.M., Yaylaoglu M., Shamloo M., Tessier-Lavigne M., Scearce-Levie K., and Weimer R.M. (2014). A death receptor 6-amyloid precursor protein pathway regulates synapse density in the mature CNS but does not contribute to Alzheimer's disease-related pathophysiology in murine models. J. Neurosci. 34, 6425–6437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mishra A., Traut M.H., Becker L., Klopstock T., Stein V., and Klein R. (2014). Genetic evidence for the adhesion protein IgSF9/Dasm1 to regulate inhibitory synapse development independent of its intracellular domain. J. Neurosci. 34, 4187–4199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Park J.I., Frantz M.G., Kast R.J., Chapman K.S., Dorton H.M., Stephany C.E., Arnett M.T., Herman D.H., and McGee A.W. (2014). Nogo receptor 1 limits tactile task performance independent of basal anatomical plasticity. PLoS One 9, e112678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pleiser S., Banchaabouchi M.A., Samol-Wolf A., Farley D., Welz T., Wellbourne-Wood J., Gehring I., Linkner J., Faix J., Riemenschneider M.J., Dietrich S., and Kerkhoff E. (2014). Enhanced fear expression in Spir-1 actin organizer mutant mice. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 93, 225–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Renier N., Wu Z., Simon D.J., Yang J., Ariel P., and Tessier-Lavigne M. (2014). iDISCO: a simple, rapid method to immunolabel large tissue samples for volume imaging. Cell 159, 896–910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Winkle C.C., McClain L.M., Valtschanoff J.G., Park C.S., Maglione C., and Gupton S.L. (2014). A novel Netrin-1-sensitive mechanism promotes local SNARE-mediated exocytosis during axon branching. J. Cell Biol. 205, 217–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhan Y., Paolicelli R.C., Sforazzini F., Weinhard L., Bolasco G., Pagani F., Vyssotski A.L., Bifone A., Gozzi A., Ragozzino D., and Gross C.T. (2014). Deficient neuron-microglia signaling results in impaired functional brain connectivity and social behavior. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 400–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lauterborn J.C., Jafari M., Babayan A.H., and Gall C.M. (2015). Environmental enrichment reveals effects of genotype on hippocampal spine morphologies in the mouse model of Fragile X Syndrome. Cereb. Cortex 25, 516–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Murmu R.P., Li W., Szepesi Z., and Li J.Y. (2015). Altered sensory experience exacerbates stable dendritic spine and synapse loss in a mouse model of Huntington's disease. J. Neurosci. 35, 287–298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhan Y. (2015). Theta frequency prefrontal-hippocampal driving relationship during free exploration in mice. Neuroscience 300, 554–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang H., Wu L., Pchitskaya E., Zakharova O., Saito T., Saido T., and Bezprozvanny I. (2015). Neuronal store-operated calcium entry and mushroom spine loss in amyloid precursor protein knock-in mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. 35, 13275–13286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sajo M., Ellis-Davies G., and Morishita H. (2016). Lynx1 limits dendritic spine turnover in the adult visual cortex. J. Neurosci. 36, 9472–9478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zou C., Crux S., Marinesco S., Montagna E., Sgobio C., Shi Y., Shi S., Zhu K., Dorostkar M.M., Muller U.C., and Herms J. (2016). Amyloid precursor protein maintains constitutive and adaptive plasticity of dendritic spines in adult brain by regulating D-serine homeostasis. EMBO J. 35, 2213–2222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guo C., Peng J., Zhang Y., Li A., Li Y., Yuan J., Xu X., Ren M., Gong H., and Chen S. (2017). Single-axon level morphological analysis of corticofugal projection neurons in mouse barrel field. Sci. Rep. 7, 2846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wohleb E.S., Terwilliger R., Duman C.H., and Duman R.S. (2018). Stress-induced neuronal colony stimulating factor 1 provokes microglia-mediated neuronal remodeling and depressive-like behavior. Biol. Psychiatry 83, 38–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hoschouer E.L., Basso D.M., and Jakeman L.B. (2010). Aberrant sensory responses are dependent on lesion severity after spinal cord contusion injury in mice. Pain 148, 328–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Leblond H., L'Esperance M., Orsal D., and Rossignol S. (2003). Treadmill locomotion in the intact and spinal mouse. J. Neurosci. 23, 11411–11419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hansen C.N., Fisher L.C., Deibert R.J., Jakeman L.B., Zhang H., Noble-Haeusslein L., White S., and Basso D.M. (2013). Elevated MMP-9 in the lumbar cord early after thoracic spinal cord injury impedes motor relearning in mice. J. Neurosci. 33, 13101–13111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ghasemlou N., Kerr B.J., and David S. (2005). Tissue displacement and impact force are important contributors to outcome after spinal cord contusion injury. Exp. Neurol. 196, 9–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ma M., Wei P., Wei T., Ransohoff R.M., and Jakeman L.B. (2004). Enhanced axonal growth into a spinal cord contusion injury site in a strain of mouse (129X1/SvJ) with a diminished inflammatory response. J. Comp. Neurol. 474, 469–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ma M., Basso D.M., Walters P., Stokes B.T., and Jakeman L.B. (2001). Behavioral and histological outcomes following graded spinal cord contusion injury in the C57Bl/6 mouse. Exp. Neurol. 169, 239–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rabchevsky A.G., Fugaccia I., Sullivan P.G., and Scheff S.W. (2001). Cyclosporin A treatment following spinal cord injury to the rat: behavioral effects and stereological assessment of tissue sparing. J. Neurotrauma 18, 513–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sorge R.E., Martin L.J., Isbester K.A., Sotocinal S.G., Rosen S., Tuttle A.H., Wieskopf J.S., Acland E.L., Dokova A., Kadoura B., Leger P., Mapplebeck J.C., McPhail M., Delaney A., Wigerblad G., Schumann A.P., Quinn T., Frasnelli J., Svensson C.I., Sternberg W.F., and Mogil J.S. (2014). Olfactory exposure to males, including men, causes stress and related analgesia in rodents. Nat. Methods 11, 629–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fandel T.M., Trivedi A., Nicholas C.R., Zhang H., Chen J., Martinez A.F., Noble-Haeusslein L.J., and Kriegstein A.R. (2016). Transplanted human stem cell-derived interneuron precursors mitigate mouse bladder dysfunction and central neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury. Cell Stem Cell 19, 544–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chaplan S.R., Bach F.W., Pogrel J.W., Chung J.M., and Yaksh T.L. (1994). Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J. Neurosci. Methods 53, 55–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Detloff M.R., Clark L.M., Hutchinson K.J., Kloos A.D., Fisher L.C., and Basso D.M. (2010). Validity of acute and chronic tactile sensory testing after spinal cord injury in rats. Exp. Neurol. 225, 366–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hargreaves K., Dubner R., Brown F., Flores C., and Joris J. (1988). A new and sensitive method for measuring thermal nociception in cutaneous hyperalgesia. Pain 32, 77–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hoschouer E.L., Yin F.Q., and Jakeman L.B. (2009). L1 cell adhesion molecule is essential for the maintenance of hyperalgesia after spinal cord injury. Exp. Neurol. 216, 22–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Meisner J.G., Marsh A.D., and Marsh D.R. (2010). Loss of GABAergic interneurons in laminae I-III of the spinal cord dorsal horn contributes to reduced GABAergic tone and neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 27, 729–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chen M.J., Kress B., Han X., Moll K., Peng W., Ji R.R., and Nedergaard M. (2012). Astrocytic Cx43 hemichannels and gap junctions play a crucial role in development of chronic neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury. Glia 60, 1660–1670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.David B.T., Ratnayake A., Amarante M.A., Reddy N.P., Dong W., Sampath S., Heary R.F., and Elkabes S. (2013). A toll-like receptor 9 antagonist reduces pain hypersensitivity and the inflammatory response in spinal cord injury. Neurobiol. Dis. 54, 194–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Murakami T., Kanchiku T., Suzuki H., Imajo Y., Yoshida Y., Nomura H., Cui D., Ishikawa T., Ikeda E., and Taguchi T. (2013). Anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody reduces neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury in mice. Exp. Ther. Med. 6, 1194–1198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tep C., Lim T.H., Ko P.O., Getahun S., Ryu J.C., Goettl V.M., Massa S.M., Basso D.M., Longo F.M., and Yoon S.O. (2013). Oral administration of a small molecule targeted to block proNGF binding to p75 promotes myelin sparing and functional recovery after spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci. 33, 397–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Novrup H.G., Bracchi-Ricard V., Ellman D.G., Ricard J., Jain A., Runko E., Lyck L., Yli-Karjanmaa M., Szymkowski D.E., Pearse D.D., Lambertsen K.L., and Bethea J.R. (2014). Central but not systemic administration of XPro1595 is therapeutic following moderate spinal cord injury in mice. J. Neuroinflammation 11, 159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wu J., Zhao Z., Sabirzhanov B., Stoica B.A., Kumar A., Luo T., Skovira J., and Faden A.I. (2014). Spinal cord injury causes brain inflammation associated with cognitive and affective changes: role of cell cycle pathways. J Neurosci 34, 10989–11006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nees T.A., Tappe-Theodor A., Sliwinski C., Motsch M., Rupp R., Kuner R., Weidner N., and Blesch A. (2016). Early-onset treadmill training reduces mechanical allodynia and modulates calcitonin gene-related peptide fiber density in lamina III/IV in a mouse model of spinal cord contusion injury. Pain 157, 687–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tateda S., Kanno H., Ozawa H., Sekiguchi A., Yahata K., Yamaya S., and Itoi E. (2017). Rapamycin suppresses microglial activation and reduces the development of neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury. J. Orthop. Res. 35, 93–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Qian J., Zhu W., Lu M., Ni B., and Yang J. (2017). D-beta-hydroxybutyrate promotes functional recovery and relieves pain hypersensitivity in mice with spinal cord injury. Br. J. Pharmacol. 174, 1961–1971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Matyas J.J., O'Driscoll C.M., Yu L., Coll-Miro M., Daugherty S., Renn C.L., Faden A.I., Dorsey S.G., and Wu J. (2017). Truncated TrkB.T1-mediated astrocyte dysfunction contributes to impaired motor function and neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci. 37, 3956–3971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Li X.M., Meng J., Li L.T., Guo T., Yang L.K., Shi Q.X., Li X.B., Chen Y., Yang Q., and Zhao J.N. (2017). Effect of ZBD-2 on chronic pain, depressive-like behaviors, and recovery of motor function following spinal cord injury in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 322, 92–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tarlov I.M. and Klinger H. (1954). Spinal Cord Compression Studies. II. Time limits for recovery after acute compression in dogs. AMA Arch. Neurol. Psychiatry 71, 271–290 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cha J., Heng C., Reinkensmeyer D.J., Roy R.R., Edgerton V.R., and De Leon R.D. (2007). Locomotor ability in spinal rats is dependent on the amount of activity imposed on the hindlimbs during treadmill training. J. Neurotrauma 24, 1000–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rossignol S. and Frigon A. (2011). Recovery of locomotion after spinal cord injury: some facts and mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 34, 413–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]