ABSTRACT

We identified four novel nonpeptidic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) protease inhibitors (PIs), GRL-078, -079, -077, and -058, containing an alkylamine at the C-5 position of P2 tetrahydropyrano-tetrahydrofuran (Tp-THF) and a P2′ cyclopropyl (Cp) (or isopropyl)-aminobenzothiazole (Abt) moiety. Their 50% effective concentrations (EC50s) were 2.5 to 30 nM against wild-type HIV-1NL4-3, 0.3 to 6.7 nM against HIV-2EHO, and 0.9 to 90 nM against laboratory-selected PI-resistant HIV-1 and clinical HIV-1 variants resistant to multiple FDA-approved PIs (HIVMDR). GRL-078, -079, -077, and -058 also effectively blocked the replication of HIV-1 variants highly resistant to darunavir (DRV) (HIVDRVrp51), with EC50s of 38, 62, 61, and 90 nM, respectively, while four FDA-approved PIs examined (amprenavir, atazanavir, lopinavir [LPV], and DRV) had virtually no activity (EC50s of >1,000 nM) against HIVDRVrp51. Structurally, GRL-078, -079, and -058 form strong hydrogen bond interactions between Tp-THF modified at C-5 and Asp29/Asp30/Gly48 of wild-type protease, while the P2′ Cp-Abt group forms strong hydrogen bonds with Asp30′. The Tp-THF and Cp-Abt moieties also have good nonpolar interactions with protease residues located in the flap region. For selection with LPV and DRV by use of a mixture of 11 HIVMDR strains (HIV11MIX), HIV11MIX became highly resistant to LPV and DRV over 13 to 32 and 32 to 41 weeks, respectively. However, for selection with GRL-079 and GRL-058, HIV11MIX failed to replicate at >0.08 μM and >0.2 μM, respectively. Thermal stability results supported the highly favorable anti-HIV-1 potency of GRL-079 as well as other PIs. The present data strongly suggest that the P2 Tp-THF group modified at C-5 and the P2′ Abt group contribute to the potent anti-HIV-1 profiles of the four PIs against HIV-1NL4-3 and a wide spectrum of HIVMDR strains.

KEYWORDS: AIDS, HIV-1, protease, protease inhibitors

INTRODUCTION

Combined antiretroviral therapy (cART) for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection and AIDS has drastically improved clinical features of HIV-1/AIDS and elongated the life expectancies of HIV-1-infected individuals in both developing and industrially advanced nations (1–3). However, the eradication of HIV-1 is currently elusive, mainly due to the presence of HIV-1 reservoirs that remain dormant in various areas of the body, such as the central nervous system (CNS) and abdominal lymphoid organs (4, 5). Moreover, a variety of issues with cART, including drug toxicities, emergence of drug-resistant HIV-1 variants, development of various cancers due to cART-elongated survival, limited restoration of immunologic functions, and increasing costs of medications, remain to be addressed in providing optimal treatment for HIV-1-infected individuals.

HIV-1 protease inhibitors (PIs) are among the most important classes of antiretroviral medications in cART. They act by inhibiting the ability of HIV-1 protease (PR) to cleave polyproteins and generate mature virions (6). PR is an essential component of the HIV-1 life cycle and serves as a primary target in developing antiretroviral agents (7). However, various amino acid substitutions occurring in PR compromise the binding of PIs to PR, thereby decreasing or nullifying the efficacy of PIs (8). In this regard, the error-prone proviral DNA synthesis mediated by HIV-1 reverse transcriptase and the rapid viral replication rate of ∼1011 virions/day in HIV-1-infected individuals are thought to contribute to the emergence of a wide variety of HIV-1 variants (9). Darunavir (DRV) is the latest FDA-approved PI, and its P2 ligand, 3(R),3a(S),6a(R)-bis-tetrahydrofuranylurethane (bis-THF), is known to contribute to its high efficacy against a variety of laboratory and clinical HIV-1 variants (10–12). Nevertheless, the emergence of HIV-1 variants resistant to antiretroviral agents continues to be a formidable obstacle in providing long-term treatment of HIV-1 infection (8). In fact, the emergence of HIV-1 variants highly resistant to DRV has been reported both in vivo and in vitro (13–17). Thus, novel antiretroviral agents with features such as a higher genetic barrier against the emergence of resistance, greater potency against wild-type and existing drug-resistant variants, and minimal to no adverse effects are still needed.

In our present work, we designed, synthesized, and characterized four nonpeptidic HIV-1 PIs, namely, GRL-078, -079, -077, and -058. Each compound contains a P2 alkylamine tetrahydropyrano-tetrahydrofuran (Tp-THF) functional moiety modified at C-5 and a P2′ cyclopropyl (Cp) (or isopropyl [Iso])-aminobenzothiazole (Abt) moiety. Here we demonstrate that the four PIs exhibit highly favorable antiretroviral profiles against HIV-1NL4-3, HIV-2EHO, and HIV-1 variants resistant to multiple FDA-approved PIs (HIVMDR strains), including an HIV-1 variant highly resistant to darunavir (HIVDRVrp51). We also found high genetic barriers for selection with GRL-079 and -058 by use of a mixture of 11 HIVMDR strains (HIV11MIX) as a starting viral population. Structural analyses suggest that polar and nonpolar interactions of the PIs with wild-type PR (PRWT) contribute to their potencies against HIV-1NL4-3 and multidrug-resistant variants.

RESULTS

GRL-078 and -079 have activity against laboratory-selected HIV-1 variants.

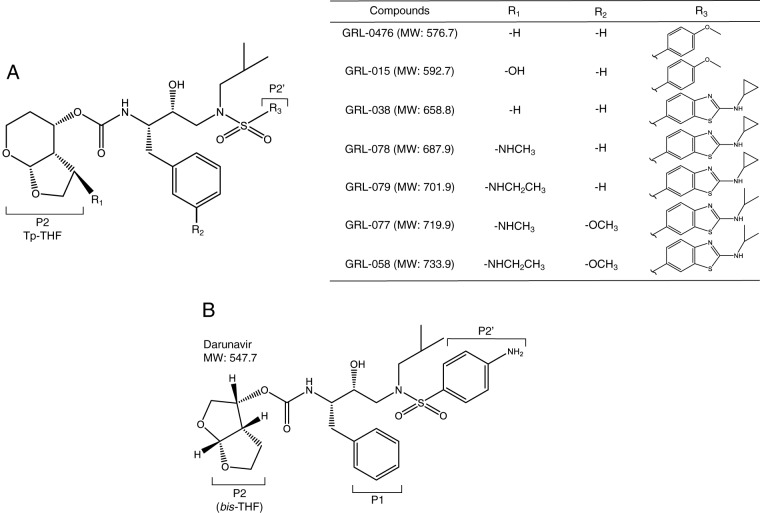

We previously reported GRL-015, a nonpeptidic HIV-1 PI containing a bicyclic P2 functional group, Tp-THF, with a C-5-hydroxyl moiety and a P2′ methoxybenzene group (Fig. 1). GRL-015 demonstrated potent antiviral activity not only against HIV-1NL4-3 but also against a variety of multi-PI-resistant HIV-1 variants (18). However, in line with our previous results (18), GRL-015 was less potent against the most DRV-resistant variant, HIVDRVrp51 (50% effective concentration [EC50] = 581 nM), though it was highly potent against HIV-1NL4-3 (EC50 = 3.5 nM) (Table 1). GRL-0476, which also has a P2 Tp-THF moiety but lacks a C-5 substitution (Fig. 1), was also potent against HIV-1NL4-3 (EC50 = 4.4 nM) but had lost its activity against HIVDRVrp51 (EC50 > 1,000 nM) (Table 1). Thus, it was thought that the presence of the C-5-hydroxyl group of Tp-THF renders GRL-015 more potent against HIVDRVrp51. We also designed and synthesized GRL-038, which has the same structure as that of GRL-0476, but with a P2′ Cp-Abt (cyclopropyl-aminobenzothiazole) moiety (Fig. 1). This compound was highly potent against HIV-1NL4-3, with an EC50 of 0.6 nM. Moreover, GRL-038 had greater antiviral activity than that of GRL-0476 against two HIVDRVr strains (HIVDRVrp10 and HIVDRVrp30) but had lost activity against HIVDRVrp51 (EC50 > 1,000 nM) (Table 1). Thus, we further designed novel PIs with Cp-Abt at the P2′ position and replaced the C-5-hydroxyl group with new alkylamine moieties in the P2 Tp-THF group, thereby generating two novel PIs, GRL-078 and -079 (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

(A) Structures of GRL-0476, -015, -038, -078, -079, -077, and -058. (B) The structure of darunavir is shown as a reference.

TABLE 1.

Antiviral activities of GRL-078, -079, -077, and -058 against laboratory-selected resistant HIV-1 strainsa

| Virus | Mean EC50 (nM) ± SD (fold change) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APV | ATV | LPV | DRV | GRL-0476 | GRL-015 | GRL-038 | GRL-078 | GRL-079 | GRL-077 | GRL-058 | |

| HIV-1NL4-3 | 37 ± 8.0 | 4.7 ± 0.1 | 50 ± 9.0 | 3.9 ± 0.5 | 4.4 ± 0.1 | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 4.2 ± 0.1 | 3.3 ± 0.7 | 21 ± 3.5 | 3.5 ± 0.4 |

| HIVAPV-5 μM | >1,000 (>27) | 3.7 ± 1.7 (0.8) | 285 ± 16 (5.7) | 288 ± 129 (74) | ND | ND | 6.7 ± 2.9 (11) | 4.4 ± 1.1 (1.0) | 3.7 ± 0.01 (1.1) | 25 ± 14 (1.2) | 6.9 ± 1.0 (2.0) |

| HIVATV-5 μM | 263 ± 36 (7.1) | >1,000 (>213) | 197 ± 110 (3.9) | 4.6 ± 0.4 (1.2) | ND | ND | 0.2 ± 0.1 (0.3) | 3.1 ± 0.4 (0.7) | 0.9 ± 0.3 (0.3) | 2.5 ± 0.1 (0.1) | 3.3 ± 2.8 (0.9) |

| HIVIDV-5 μM | >1,000 (>27) | >1,000 (>213) | >1,000 (>20) | 38 ± 1.4 (9.7) | ND | ND | 4.3 ± 0.5 (7.2) | 2.9 ± 0.5 (0.7) | 3.8 ± 0.5 (1.2) | 3.2 ± 0.8 (0.2) | 3.0 ± 2.2 (0.9) |

| HIVLPV-5 μM | >1,000 (>27) | >1,000 (>213) | >1,000 (>20) | 38 ± 2.8 (9.7) | ND | ND | 52 ± 13 (87) | 5.9 ± 1.8 (1.4) | 3.9 ± 0.4 (1.2) | 26 ± 7.8 (1.2) | 35 ± 4.3 (10) |

| HIVNFV-5 μM | 59 ± 1.1 (1.6) | 19 ± 4.7 (4.0) | 26 ± 10 (0.5) | 1.8 ± 0.05 (0.5) | ND | ND | 1.6 ± 0.5 (2.7) | 2.4 ± 1.3 (0.6) | 3.4 ± 0.3 (1.0) | 43 ± 5.1 (2.0) | 3.2 ± 0.1 (0.9) |

| HIVRTV-5 μM | >1,000 (>27) | 54 ± 19 (11) | >1,000 (>20) | 43 ± 9.2 (11) | ND | ND | 3.2 ± 1.0 (5.3) | 3.2 ± 0.2 (0.8) | 3.5 ± 1.0 (1.1) | 8.7 ± 1.8 (0.4) | 4.4 ± 1.2 (1.3) |

| HIVSQV-5 μM | >1,000 (>27) | >1,000 (>213) | >1,000 (>20) | 63 ± 20 (16) | ND | ND | 46 ± 10 (77) | 27 ± 6.6 (6.4) | 4.4 ± 1.7 (1.3) | 51 ± 10 (2.4) | 4.9 ± 0.2 (1.4) |

| HIVTPV-15 μM | >1,000 (>27) | >1,000 (>213) | >1,000 (>20) | 46 ± 2.1 (12) | ND | ND | 38 ± 4.4 (63) | 38 ± 2.3 (9.0) | 6.3 ± 0.9 (1.9) | 24 ± 9.9 (1.1) | 7.7 ± 2.8 (2.2) |

| HIVDRVrp10 | >1,000 (>27) | >1,000 (>213) | 402 ± 17 (8.0) | 32 ± 2.0 (8.2) | 427 ± 110 (97) | 14 ± 0.2 (4.0) | 34 ± 3.0 (57) | 2.1 ± 0.6 (0.5) | 1.6 ± 0.4 (0.5) | 2.4 ± 0.4 (0.1) | 1.8 ± 0.9 (0.5) |

| HIVDRVrp30 | >1,000 (>27) | >1,000 (>213) | >1,000 (>20) | 626 ± 166 (161) | >1,000 (>227) | 46 ± 8.0 (13) | 64 ± 10 (107) | 2.7 ± 0.8 (0.6) | 5.1 ± 0.9 (1.5) | 16 ± 0.6 (0.8) | 16 ± 1.9 (4.6) |

| HIVDRVrp51 | >1,000 (>27) | >1,000 (>213) | >1,000 (>20) | >1,000 (>256) | >1,000 (>227) | 581 ± 60 (166) | >1,000 (>1,667) | 38 ± 8.5 (9.0) | 62 ± 16 (19) | 61 ± 14 (2.9) | 90 ± 29 (26) |

The amino acid substitutions identified in the proteases of HIVAPV-5μM, HIVATV-5μM, HIVIDV-5μM, HIVLPV-5μM, HIVNFV-5μM, HIVRTV-5μM, HIVSQV-5μM, HIVTPV-15μM, HIVDRVrp10, HIVDRVrp30, and HIVDRVrp51 compared to that of wild-type HIV-1NL4-3 include L10F/V32I/L33F/M46L/I54M/A71V, L23I/E34Q/K43I/M46I/I50L/G51A/L63P/A71V/V82A/T91A, L10F/L24I/M46I/L63P/A71V/G73S/V82T, L10F/M46I/I54V/V82A, L10F/K20T/D30N/K45I/A71V/V77I, L10I/M46L/I54V/V82A, L10I/N37D/G48V/I54V/L63P/G73C/I84V/L90M, L10I/L33I/M36I/M46I/I54V/K55R/I62V/L63P/A71V/G73S/V82T/L90M/I93L, L10I/I15V/K20R/L24I/V32I/M36I/M46L/I54V/I62V/L63P/K70Q/V82A/L88M, L10I/I15V/K20R/L24I/V32I/M36I/M46L/L63P/K70Q/V82A/I84V/L89M, and L10I/I54V/K20R/L24I/V32I/L33F/M36I/M46L/I54M/L63P/K70Q/V82I/I84V/L89M, respectively. Numbers in parentheses denote fold changes in EC50 for each isolate compared to the EC50 for wild-type HIV-1NL4-3. The data are arithmetic means ± 1 standard deviation derived from assays conducted in triplicate. ND, not determined.

As shown in Table 1, GRL-078 and -079 exhibited potent activity against HIV-1NL4-3, with EC50s of 4.2 and 3.3 nM, respectively, as determined based on the amounts of p24 Gag protein produced. We determined the activities of GRL-078 and -079 against HIV-1 variants resistant to eight FDA-approved PIs (amprenavir [APV], atazanavir [ATV], indinavir [IDV], lopinavir [LPV], nelfinavir [NFV], ritonavir [RTV], saquinavir [SQV], and tipranavir [TPV]). Seven of the PI-resistant variants (HIVAPV-5μM, HIVATV-5μM, HIVIDV-5μM, HIVLPV-5μM, HIVNFV-5μM, HIVRTV-5μM, and HIVSQV-5μM) were selected by exposing HIV-1NL4-3 to increasing concentrations of each PI, while TPV-resistant variants (HIVTPV-15μM) were selected by using HIV11MIX (13, 19). The variants acquired a variety of mutations in protease that are reportedly associated with the acquisition of viral resistance to PIs (see the footnote to Table 1). Against all of these PI-resistant viruses, GRL-078 and -079 maintained their potencies relatively well compared to those of APV, ATV, and LPV. HIVAPV-5μM, HIVATV-5μM, and HIVLPV-5μM were found to be highly resistant to APV, ATV, and LPV. The favorable antiviral profiles of the 2 novel PIs were more evident when we examined their activities against HIVDRVrp51. We found that DRV as well as APV, ATV, and LPV failed to block the replication of HIVDRVrp51 (EC50 > 1,000 nM), while GRL-078 and -079 effectively blocked HIVDRVrp51 replication, with EC50s of 38 and 62 nM, respectively.

GRL-078, -079, -077, and -058 are potent against PI-resistant HIV-1 clinical isolates.

Two other newly generated PIs, GRL-077 and -058, contain a P2′ isopropyl-aminobenzothiazole (Iso-Abt) group as well as C-5-aminomethyl- and -aminoethyl-Tp-THF, respectively (Fig. 1). We found that all four novel compounds (GRL-078, -079, -077, and -058) were highly active against the six recombinant multidrug-resistant infectious HIV-1 clones examined (rCLHIVF16, rCLHIVF39, rCLHIVF71, rCLHIVM45, rCLHIVT44, and rCLHIVT48). All six HIV-1 clones had 16 to 23 amino acid substitutions in PR compared to the PR of the index HIV-1 strain, HIV-1NL4-3 (see the footnote to Table 2). The activities of the FDA-approved PIs APV, ATV, and LPV were significantly compromised, with EC50s that were mostly over 1,000 nM. Many of the variants examined were also found to be much more resistant even to DRV, with EC50s of 37 to >1,000 nM, and the fold changes for DRV relative to DRV's activity against HIV-1NL4-3 were pronounced (9.5- to >256-fold). However, all the novel PIs examined here (GRL-078, -079, -077, and -058) quite effectively blocked the replication of the recombinant infectious clones, with EC50s of 2.8 to 53 nM (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Antiviral activities of GRL-078, -079, -077, and -058 against clinical isolatesa

| Virus | Mean EC50 (nM) ± SD (fold change) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APV | ATV | LPV | DRV | GRL-078 | GRL-079 | GRL-077 | GRL-058 | |

| HIV-1NL4-3 | 37 ± 8.0 | 4.7 ± 0.1 | 50 ± 9.0 | 3.9 ± 0.5 | 4.2 ± 0.1 | 3.3 ± 0.7 | 21 ± 3.5 | 3.5 ± 0.4 |

| rCLHIVF16 | >1,000 (>27) | >1,000 (>213) | >1,000 (>20) | >1,000 (>256) | 3.0 ± 1.0 (0.7) | 2.8 ± 0.6 (0.8) | 22 ± 2.8 (1.1) | 3.2 ± 0.04 (0.9) |

| rCLHIVF39 | >1,000 (>27) | >1,000 (>213) | 420 ± 23 (8.4) | >1,000 (>256) | 4.3 ± 0.6 (1.0) | 5.1 ± 0.8 (1.5) | 42 ± 1.3 (2.0) | 53 ± 3.5 (15) |

| rCLHIVF71 | >1,000 (>27) | >1,000 (>213) | 366 ± 150 (7.3) | 37 ± 14 (9.5) | 3.4 ± 1.8 (0.8) | 2.9 ± 1.2 (0.9) | 4.7 ± 1.5 (0.2) | 24 ± 12 (6.9) |

| rCLHIVM45 | >1,000 (>27) | >1,000 (>213) | 232 ± 35 (4.6) | 368 ± 169 (94) | 25 ± 16 (6.0) | 5.4 ± 0.4 (1.6) | 35 ± 2.0 (1.7) | 15 ± 1.0 (4.3) |

| rCLHIVT44 | >1,000 (>27) | >1,000 (>213) | >1,000 (>20) | 425 ± 183 (109) | 48 ± 3.0 (11) | 43 ± 0.5 (13) | 48 ± 12 (2.3) | 49 ± 3.0 (14) |

| rCLHIVT48 | >1,000 (>27) | >1,000 (>213) | >1,000 (>20) | 350 ± 29 (90) | 5.1 ± 1.6 (1.2) | 4.4 ± 0.5 (1.3) | 27 ± 5.4 (1.3) | 9.0 ± 1.4 (2.6) |

The amino acid substitutions identified in the proteases of rCLHIVF16, rCLHIVF39, rCLHIVF71, rCLHIVM45, rCLHIVT44, and rCLHIVT48 compared to that of wild-type HIV-1NL4-3 include L10F/V11I/I13V/L19Q/K20M/V32I/L33V/E35A/M36I/M46I/I47V/I54M/R57K/I62V/L63P/I64V/G73T/T74A/I84V/L89V/L90M, L10V/V11I/I13V/K14R/I15V/K20T/V32I/L33F/M36I/R41K/M46L/I54L/R57K/D60E/L63P/G68E/K70T/A71I/I72M/G73S/I84V/L89V/L90M/I93I, L10I/V11I/T12K/I13V/K20V/V32I/L33F/E35G/M36I/N37D/M46L/I47V/I54M/R57K/Q58E/L63P/I64V/I66V/A71V/G73S/I84V/L89M/L90M, L10F/V11I/T12P/I13V/I15V/L19P/K20T/V32I/L33F/E35G/M36I/I54V/I62V/L63P/K70T/A71V/G73S/P79A/I84V/L89V/L90M, L10F/I13V/G16A/L19V/L33F/E34Q/K43I/M46L/G51A/I54M/L63P/I64M/A71V/I72M/G73A/I84V/L90M, and L10I/I13V/I15V/L19V/L24I/V32I/L33F/K43E/M46L/I54L/D60E/L63P/A71V/I72V/V82A/I84V, respectively. Numbers in parentheses denote fold changes in EC50 for each isolate compared to the EC50 for wild-type HIV-1NL4-3. The data are shown as arithmetic means ± 1 standard deviation derived from assays conducted in triplicate.

GRL-078, -079, -077, and -058 exhibit potent activity against HIV-2EHO and favorable cytotoxicity.

The amino acid substitutions in PR identified in HIV-1 variants that acquired high-level resistance to various PIs are also often seen in PRs of HIV-2 strains (20). Indeed, a variety of PIs developed in the 1990s and 2000s, such as APV and ATV, are not active against multi-PI-resistant HIV-1 variants or HIV-2 strains (21). In line with the data from previous studies (18), both APV and ATV were significantly less active against HIV-2EHO than against HIV-1NL4-3 (Table 3). DRV has been shown to be unique in this regard, in that DRV remains active against a variety of PI-resistant HIV-1 variants and HIV-2 strains, as shown in Table 3. Thus, we also examined the activities of GRL-078, -079, -077, and -058 against HIV-2EHO in the present study. The activities of GRL-078 and -058 against HIV-1NL4-3 were comparable to those against HIV-2EHO. Interestingly, GRL-079 and -077 turned out to be more potent against HIV-2EHO (EC50s of 0.3 and 6.7 nM, respectively) than against HIV-1NL4-3 (EC50s of 2.5 and 30 nM, respectively). After exposing MT-4 cells to each of the four PIs for 7 days, cytotoxicity profiles of GRL-078, -079, and -058 were shown to be relatively favorable, with 50% cytotoxic concentrations (CC50) ranging from 38 to 40 μM, which resulted in selectivity indices of 10,900, 16,000, and 14,100, respectively. The selectivity index of GRL-077 was much lower, with a value of 1,100 (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Antiretroviral activities of GRL-078, -079, -077, and -058 against HIV-1NL4-3 and HIV-2EHO and their cytotoxicities in vitroa

| Compound | Mean EC50 (nM) ± SD |

CC50 (μM)b | Selectivity indexc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1NL4-3 | HIV-2EHO | |||

| APV | 23 ± 2.6 | 291 ± 3.6 | 208 | 9,000 |

| ATV | 3.7 ± 1.9 | 36 ± 3.6 | 45 | 12,200 |

| LPV | 26 ± 19 | 7.1 ± 3.9 | 60 | 2,300 |

| DRV | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 7.1 ± 1.5 | 177 | 63,200 |

| GRL-078 | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 3.3 ± 0.03 | 38 | 10,900 |

| GRL-079 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.02 | 40 | 16,000 |

| GRL-077 | 30 ± 1.6 | 6.7 ± 1.7 | 33 | 1,100 |

| GRL-058 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 2.5 ± 1.2 | 38 | 14,100 |

The data are shown as arithmetic means ± 1 standard deviation derived from assays conducted in triplicate.

The concentration required to reduce the number of cells by 50% compared to that of no-drug controls.

Each selectivity index denotes the ratio of CC50 to EC50 against HIV-1NL4-3.

GRL-078, -079, and -058 form strong polar and van der Waals interactions with many key PR residues.

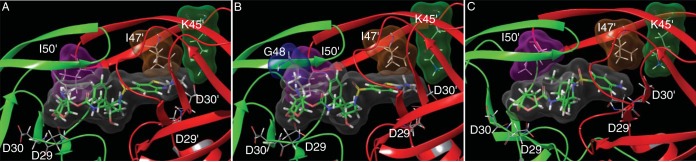

Structural analyses of three PIs, GRL-078, -079, and -058, modeled into the activity site cavity of wild-type HIV-1 protease (PRWT) demonstrated the critical interactions between the PIs and HIV-1 PR (Fig. 2). The oxygen atoms of the Tp-THF ring in the P2 position have strong polar interactions with the backbone NH groups of Asp29 and Asp30 (Fig. 2). The amide NH groups of all three PIs form a strong hydrogen bond interaction with the backbone carbonyl of Gly27, and the hydroxyl group forms hydrogen bond interactions with the catalytic Asp25 (which is protonated) and Asp25′ residues. The carbonyl and sulfonyl oxygens form polar interactions with Ile50 and Ile50′, located in PR's flap, through a bridging water molecule. DRV also has these polar interactions with PR (10). GRL-079 has an aminoethyl substituent at the C-5 position of Tp-THF, whose nitrogen has hydrogen bond interactions with the backbone carbonyl of Gly48. Gly48 is in the flap region of PR. The P2′ Cp-Abt moiety of GRL-079 also forms several polar and van der Waals contacts with PR. The P2′ amino group forms a strong polar interaction with the side chain carboxylate of Asp30′. In addition to the interactions shown by GRL-079, the thiazole nitrogen of GRL-078 forms hydrogen bond interactions with the backbone NH of Asp30′. Whereas many PIs show hydrogen bond interactions with either the backbone NH or the side chain carboxylate of Asp30′, instances of such direct hydrogen bond interactions not mediated through bridging waters are less common. GRL-058 has polar interactions with PR similar to those of GRL-079. This is not surprising considering their similar antiviral activities. We compared the nonpolar interactions of GRL-079 and DRV by analyzing the interactions of the molecular surfaces (Fig. 3). The molecular surface of GRL-079 forms much better contacts with Ile47′ and Ile50′ than those of DRV. Moreover, GRL-079 has good interactions with Lys45′. No corresponding interaction is seen for DRV.

FIG 2.

Structural modeling of PRWT complexed with GRL-078, -079, and -058. Polar contacts with PRWT made by GRL-078 (A), GRL-079 (B), GRL-058 (C), and DRV (D) are shown. One protease subunit is shown in green, while the other, identical subunit is shown in red. In each panel, the carbons for the protease inhibitors are displayed in green, while PRWT carbons are shown in gray. Nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur atoms are shown in blue, red, and yellow, respectively. Yellow dotted lines indicate hydrogen bonds.

FIG 3.

Connolly molecular surface interactions of GRL-078 (A), GRL-079 (B), and DRV (C) with selected protease residues located in the flap region. The inhibitor surfaces are shown in gray, and the surfaces for I50′, I47′, K45′, and G48 are shown in magenta, brown, green, and blue, respectively. The protease chains are shown in green and red. In each panel, the carbons for the protease inhibitors are displayed in green, while PRWT carbons are shown in gray. Nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur atoms are shown in blue, red, and yellow, respectively.

In vitro selection of HIV-1 variants resistant to GRL-079 and -058 by using HIV11MIX as a starting viral population.

With GRL-079 exhibiting the best overall antiviral profile, we chose GRL-079 to conduct the selection of drug-resistant viruses, along with GRL-058 to compare the effects of the P2′ moiety. We used a mixture of 11 HIVMDR isolates (HIV11MIX) as a starting viral population to select for drug-resistant variants against GRL-079 and -058. As shown in Fig. 4, HIV11MIX was propagated in the presence of increasing concentrations of LPV, DRV, GRL-079, or GRL-058. Since HIV-1 is known to acquire amino acid substitutions stoichiometrically at random and since selection results often vary between experiments (22, 23), we conducted the selection assay on two different occasions. The selection was carried out by passage of cell-free virus for a total of 13 to 44 weeks, with drug concentrations escalating from 0.006 to 5 μM. Nucleotide sequences of proviral DNA were determined using cell lysates of HIV-1-infected MT-4 cells at the termination of each indicated passage. HIV11MIX exposed to LPV continued to replicate in the presence of up to 5 μM LPV by 13 and 32 weeks of selection (Fig. 4). Nucleotide sequencing revealed that HIV11MIX propagating in the presence of LPV did not acquire any additional amino acid substitutions in either of the two experiments (Fig. 5A). By the end of ∼30 weeks of selection, HIV11MIX exposed to DRV was replicating in the presence of >1 μM DRV. HIV11MIX selected with DRV over 41 weeks had acquired V32I/T74S and V32I/T74S/I84V mutations in experiments 1 and 2, respectively (Fig. 5B). In contrast, HIV11MIX exposed to GRL-079 or -058 was found to be incapable of replicating in the presence of >0.2 μM drug. HIV11MIX exposed to GRL-058 had acquired only one relatively unique nonpolymorphic mutation, L24M, in protease (Fig. 5D). HIV11MIX exposed to GRL-079 had also acquired L24M and R41G mutations by the end of 37 weeks of selection in experiment 2 (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, there was a reversion of Ala82, one of the major amino acid substitutions associated with HIV-1 resistance against multiple PIs (https://hivdb.stanford.edu), back to the wild-type amino acid, Val82.

FIG 4.

In vitro selection of HIV-1 variants against GRL-079, GRL-058, DRV, and LPV. A mixture of 11 multi-PI-resistant HIV-1 isolates (HIV11MIX) was propagated in MT-4 cells in the presence of increasing concentrations of GRL-079 (○), GRL-058 (▲), DRV (□), or LPV (●). The selection process was conducted by passage of cell-free virus. Amino acid substitutions acquired in each HIV-1 variant during selection are illustrated in Fig. 5.

FIG 5.

Amino acid sequences of the proteases of HIV11MIX variants selected with LPV, DRV, GRL-079, and GRL-058 in vitro. Amino acid sequences deduced from the nucleotide sequences of the protease-encoding region of proviral DNA isolated from HIV11MIX variants selected with LPV (13 weeks for experiment 1 and 32 weeks for experiment 2) (A), DRV (32 weeks for experiment 1 and 41 weeks for experiment 2) (B), GRL-079 (32 weeks for experiment 1 and 37 weeks for experiment 2) (C), and GRL-058 (32 weeks for experiment 1 and 44 weeks for experiment 2) (D) are shown. The HIVNL4-3 and HIV11MIXWK0 amino acid sequences are displayed at the top for reference. Identity at individual amino acid positions is indicated by dots. Fractions shown on the right give the number of viruses from which each clone is presumed to have originated over the total number of clones examined.

In order to examine the possible role of the L24M substitution in HIV-1's replicability and susceptibility to GRL-079 and -058, we constructed and propagated a molecular clone of HIVNL4-3 carrying the L24M substitution (HIVNL4-3L24M) and conducted viral replication kinetic and drug susceptibility assays using both HIVNL4-3 and HIVNL4-3L24M. As shown in Fig. S1A and B in the supplemental material, there was no significant difference in both assays between the two clones. These data strongly suggest that the L24M substitution perhaps plays some role in conferring resistance to GRL-079 and -058, while the substitution alone does not significantly change the replication kinetics of HIVNL4-3L24M or its susceptibility to GRL-079 and -058.

GRL-079 demonstrates the greatest thermal stability among those of the P2 Tp-THF-containing PIs and DRV.

We next determined the thermal stabilities of P2 Tp-THF-containing PIs tested in the present study, i.e., GRL-0476, -015, -038, -058, -077, -078, and -079, as well as that of DRV, by using PRD25N. As shown in Fig. 6, PRD25N had a melting temperature (Tm) of 53.54 ± 0.08°C in the absence of compounds, while the Tm value was 56.81 ± 0.11°C (ΔTm = 3.27°C) in the presence of 50 μM DRV. GRL-0476, which has a P2′ methoxybenzene group and lacks a Tp-THF C-5 substitution, gave a Tm value close to that of DRV, at 56.05 ± 0.34°C (ΔTm = 2.51°C). GRL-015 has a Tp-THF C-5 substitution (-OH) but does not have a P2′ Abt group, and it resulted in a Tm value of 59.08 ± 0.24°C (ΔTm = 5.54°C). GRL-038, which lacks a C-5 substitution but has a P2′ Cp-Abt group, gave a Tm value of 57.99 ± 0.06°C (ΔTm = 4.45°C). Other PIs that have both a C-5 substitution and P2′ Cp-Abt or Iso-Abt had higher Tm values than those of GRL-0476 and DRV. However, it is noteworthy that GRL-079 had the greatest Tm value, 59.95 ± 0.07°C (ΔTm = 6.41°C), among the PIs with a C-5 substitution and P2′ Cp-Abt or Iso-Abt. These data suggest that GRL-079 binds most tightly to PRD25N among the PIs examined here and explain, at least in part, why GRL-079 has the best overall anti-HIV activity.

FIG 6.

Thermal stability of PRD25N with DRV or GRL-0476, -015, -038, -058, -077, -078, or -079 as determined using differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF). (A) Relative fluorescence intensities determined by DSF using Sypro Orange. (B) Tm values shown represent the temperatures at which the relative fluorescence intensity was 0.5, and ΔTm values indicate the Tm difference between protease complexed with each PI and that with no PI. SD, standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

For individuals harboring multidrug-resistant HIV-1 variants, therapeutic options tend to be limited, and the presence of such variants remains a challenging issue in treating HIV-1/AIDS. We previously reported that a hydroxyl group at the C-5 position of the P2 Tp-THF or bis-THF contributes to an increased activity of certain PIs against HIVMDR variants (18, 24). In the present study, in an attempt to further delineate the role of the C-5 modification in the P2 Tp-THF moiety, we designed and synthesized a variety of novel PIs and demonstrated that C-5 modifications with various alkylamine groups confer on those PIs highly potent activity against a wide spectrum of HIVMDR and HIVDRVr strains.

Here we demonstrate that the prototypic compound, GRL-038, without the P2 Tp-THF C-5 modification but with P2′ Cp-Abt, was approximately 6-fold more potent than DRV against HIV-1NL4-3 and exhibited substantially more favorable antiviral profiles against HIVMDR strains than those for DRV, although its ability to inhibit the replication of HIVDRVr strains was still limited (Table 1). We therefore newly designed GRL-078, -079, -077, and -058, which contain a polycyclic ligand, Tp-THF, as a P2 functional moiety with a C-5-methyl- or -ethylamine modification and a P2′ Abt moiety (Fig. 1). The four PIs potently inhibited laboratory-selected HIVMDR strains, including HIVDRVr strains (Table 1). Furthermore, upon examining these compounds against clinically isolated strains of HIV-1, we found that all four PIs had lower fold change differences against all six different clinical variants tested than those for DRV (Table 2). It is notable that GRL-038, which is structurally identical to the P2′ Cp-Abt-containing compound GRL-079, with the exception of a functional group at the C-5 position of P2 Tp-THF (Fig. 1), exerts strong activity against HIV-1NL4-3 but has decreased activity against laboratory-selected HIV-1 variants, most markedly against HIVDRVrp51 (Table 1), thus suggesting that the C-5 functional group is a critical moiety in the structure of GRL-079 and its significant potency against HIVMDR strains. Moreover, a cyclopropyl moiety has been shown, in general, to enhance pharmacological activity and oral bioavailability in various compounds (25). The cyclopropane ring has also been reported to improve other drug properties, such as entropic binding, half-life, and ability to permeate the brain (25).

Although all four PIs described above were potent against HIVMDR strains, we discerned GRL-079 to be the most promising compound overall and attempted to further delineate its genetic barrier against the emergence of HIV-1 variants. Due to the random and various amino acid substitutions that can occur over the course of selection experiments, two independent experiments were performed to corroborate the results of the selection study results with GRL-079. In both experiments, HIV11MIX readily acquired high-level resistance to LPV and DRV. There were two slightly varied profiles for the tested drugs (DRV, GRL-079, and GRL-058), with the exception of LPV. As predicted, LPV did not result in development of any amino acid substitutions during the selection process for resistant variants, most likely because most strains initially contained in HIV11MIX were derived from patients on long-term regimens that included PIs, and such constituents already had 8 to 16 amino acid substitutions in protease (26). In experiment 1, DRV acquired V32I/T74S mutations, while V32I/T74S/I84V mutations were observed in experiment 2. The V32I and I84V mutations are known to be important amino acid substitutions that confer significant DRV resistance (https://hivdb.stanford.edu/). In contrast, HIV11MIX failed to continuously replicate in the presence of GRL-079 and -058, suggesting that these compounds have a higher genetic barrier than those of both LPV and DRV. The amino acid substitutions that developed by selection with GRL-079 (L24M in experiment 1 and L24M/R51G in experiment 2) and -058 (L24M/K43T in experiment 1 and L24M in experiment 2) are not presently known to be major mutations that result in PI resistance. There was a reversion of A82 residing in the HIV11MIX starting population back to the V that is present in HIV-1NL4-3. Interestingly, the reversion of the V82A substitution back to the wild type was seen in a longitudinal study of a patient who stopped antiviral therapy (27), although the underlying mechanisms for the reversion remain to be elucidated.

The structural modeling of GRL-079 showed that it forms favorable polar and nonpolar interactions with PRWT. For example, the oxygen atoms of the P2 Tp-THF ring have strong polar interactions with the NH groups of Asp29 and Asp30, which are also seen between DRV and PRWT. These interactions with the main chain of Asp29 and Asp30 have been shown to contribute to DRV's ability to block HIVMDR replication (28). However, in HIVDRVr variants, the flap region of PRWT is reportedly destabilized, and its binding to DRV is weakened in the protein-ligand state (28). The addition of a C-5-alkylamine to Tp-THF in GRL-079 effectively allowed the formation of a hydrogen bond with the carbonyl oxygen atom of Gly48 in the flap region of PRWT, thus stabilizing the flap. GRL-079 also forms strong van der Waals interactions with PRWT. Overall, Tp-THF forms stronger molecular surface interactions than those of DRV with Ile50′ of the flap region. The cyclopropane group of P2′ Abt in GRL-079 is capable of interacting with Lys45′ and Ile47′ in PR's flap (Fig. 3). These interactions should explain, at least in part, the high potency of GRL-079 and other P2 Tp-THF-containing PIs against wild-type and PI-resistant HIV-1 variants.

In the present study, we also examined the protein thermal stability with the present PIs by using PRD25N. The D25N substitution allows the measurement of thermal stability by disrupting the autoproteolytic cleavage of PR (29, 30). GRL-079 was found to form the most stable protein-ligand complex among those for the P2 Tp-THF-containing PIs and DRV. Notably, GRL-0476, which differs from GRL-079 by an alternate P2′ moiety and the absence of C-5-substituted Tp-THF, had much-less-stable interactions with PRD25N, thus strongly suggesting that these two structural differences are important in providing substantial thermal stability and improving the antiviral profile of GRL-079.

The aforementioned features of GRL-079 strongly suggest that the compound is a promising candidate as a novel anti-HIV therapeutic and that GRL-079 should be investigated further for potential clinical development. The structure-activity relationships of the various C-5 substitutions of the P2 Tp-THF moiety demonstrated in the present study should also provide in-depth insight into the design of further potent and resistance-repelling novel PIs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

MT-4 cell lines were grown in RPMI 1640-based culture medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (PAA Laboratories GmbH, Lin, Austria). The following HIV-1 and HIV-2 strains were used for drug susceptibility assays: wild-type HIV-1NL4-3, HIV-2EHO, six HIV-1 clinical isolates (rCLHIVF16, rCLHIVF39, rCLHIVF71, rCLHIVM45, rCLHIVT44, and rCLHIVT48), eight laboratory-selected PI-resistant strains (HIVAPV-5μM, HIVATV-5μM, HIVIDV-5μM, HIVLPV-5μM, HIVNFV-5μM, HIVRTV-5μM, HIVSQV-5μM, and HIVTPV-15μM) (13, 19, 26), and three highly DRV-resistant HIV-1 variants (HIVDRVrp10, HIVDRVrp30, and HIVDRVrp51). In the variant names, APV, ATV, IDV, LPV, NFV, RTV, SQV, and TPV denote amprenavir, atazanavir, indinavir, lopinavir, nelfinavir, ritonavir, saquinavir, and tipranavir, respectively (13). The six HIV-1 clinical isolates were propagated using HIV-1NL4-3-based infectious molecular clones (generous gifts from Robert Shafer of Stanford University), which were generated by ligating patient-derived amplicons encompassing approximately 200 nucleotides of the Gag gene (beginning at the unique ApaI restriction site), the entire PR gene, and the first 72 nucleotides of the reverse transcriptase gene by using the expression vector pNLPFB, a kind gift from Tomozumi Imamichi of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Recombinant clinical HIV-1 isolates were obtained from patients with multi-PI resistance (18). The eight laboratory-selected PI-resistant HIV-1 variants were obtained as previously described (13, 19, 26). Briefly, the variants were generated in vitro by propagating HIV-1NL4-3 (for HIVAPV-5μM, HIVATV-5μM, HIVIDV-5μM, HIVLPV-5μM, HIVNFV-5μM, HIVRTV-5μM, and HIVSQV-5μM) or a mixture of 11 highly multi-PI-resistant clinical HIV-1 strains (HIV11MIX; for HIVTPV-15μM) in the presence of increasing concentrations of each PI, up to 5 μM or 15 μM. The three highly DRV-resistant HIV-1 variants were generated using a mixture of eight highly multi-PI-resistant clinical HIV-1 strains (HIV8MIX) as previously described (13). Notably, all eight highly multi-PI-resistant clinical HIV-1 strains were from HIV-1-infected individuals who had serially received a number of antiretroviral agents, including multiple nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), and experienced treatment failure (11). Thus, the three DRV-resistant HIV-1 variants (HIVDRVrp10, HIVDRVrp30, and HIVDRVrp51) contain a variety of NRTI resistance-associated amino acid substitutions in reverse transcriptase. For example, HIVDRVrp51 contains M41L, E44D, D67N, T69D, M184V, L210W, T215Y/F, D218E, and K219Q/N substitutions in its reverse transcriptase and is highly resistant to azidothymidine, lamivudine, tenofovir disoproxil, and abacavir (M. Aoki and H. Mitsuya, submitted for publication).

Antiviral agents.

Four novel C-5-alkylamine-Tp-THF-containing nonpeptidic PIs, GRL-078, -079, -077, and -058 (Fig. 1), whose molecular weights are 687.9, 701.9, 719.9, and 733.9, respectively, were employed. The methods used to synthesize these PIs will be published elsewhere by A. K. Ghosh, C. D. Martyr, and H. Mitsuya. Three additional PIs (GRL-0476 [18], -015 [18], and -038), whose molecular weights are 576.7, 592.7, and 658.8, respectively, were also employed. The synthetic method for GRL-038 will also be published elsewhere by Ghosh et al. DRV was synthesized as previously described (31). Amprenavir (APV), lopinavir (LPV), and atazanavir (ATV) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Drug susceptibility assay.

Susceptibilities of HIV-1NL4-3 and HIV-2EHO to various compounds were determined as previously described (22), with minor modifications. Briefly, MT-4 cells (104 cells/200 μl) were exposed to 50 50% tissue culture infective doses (TCID50s) of HIV-1NL4-3 or HIV-2EHO in the presence or absence of various concentrations of agents in 96-well microtiter culture plates, followed by incubation at 37°C for 7 days. At the conclusion of the 7-day culture, 10 μl of Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) solution was added to each well, followed by further incubation at 37°C for 3 h. The optical density was measured using a kinetic microplate reader (Vmax; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). To determine the drug susceptibilities of infectious molecular HIV-1 clones and each PI-selected HIV-1 variant, the following method was used. MT-4 cells (104 cells/200 μl) were exposed to 50 TCID50s of infectious molecular HIV-1 clones and PI-selected HIV-1 variants in the presence or absence of various concentrations of drugs and were incubated at 37°C. On day 7 of culture, the supernatant was harvested, and the amount of p24 Gag protein was determined using a fully automated chemiluminescence enzyme immunoassay system (Lumipulse F; Fujirebio Inc., Tokyo, Japan) (32). The drug concentrations that suppressed the production of p24 Gag protein by 50% (50% effective concentrations [EC50s]) were determined by comparison with the level of p24 production in drug-free control cell cultures. Assays were all performed in triplicate.

To measure the cytotoxicity of the PIs, MT-4 cells (104 cells/200 μl) were plated in 96-well culture plates and continuously exposed to various concentrations of each compound. After 7 days of incubation, the number of viable cells in each well was determined using Cell Counting Kit-8. The 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) was determined as the concentration required to reduce the number of cells by 50% compared to that of drug-free control cultures.

Structural analyses of GRL-078, -079, and -058 interactions with wild-type HIV-1 protease.

Starting from the X-ray crystal structure of GRL-142 complexed with wild-type PR (PRWT) (Protein Data Bank [PDB] entry 5TYS), initial structures of GRL-078, -079, and -058 in complex with PRWT were built using Maestro (version 10.7.015, release 2016-3). These structures were fully minimized using an OPLS3 force field and used for subsequent analyses. Hydrogens were added to the crystal structure of DRV in complex with PRWT (PDB entry 4HLA) (33), protonation states of aspartates were assigned, and a restrained minimization was performed. A cutoff distance of 3.0 Å between a polar hydrogen and an oxygen or nitrogen atom, a minimum donor angle of 60° between D-H-A, and a minimum acceptor angle of 90° between H-A-B were used to define the presence of hydrogen bonds (“D,” “A,” and “B” stand for “donor,” “acceptor,” and “atom connected to acceptor,” respectively). Connolly molecular surfaces for the inhibitors and selected PR residues from the active site were generated using a water sphere with a radius of 1.4 Å as a probe. Software tools from Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, as implemented in the Maestro interface, were used for model building, visualization, and analysis.

In vitro selection of HIV-1 variants resistant to PIs.

Selection attempts to obtain HIV-1 variants resistant to GRL-079, GRL-058, DRV, and LPV were made as previously described (13, 19, 26). Briefly, 30 TCID50s of each of 11 HIV-1 variants highly resistant to multiple PIs (HIVA, HIVB, HIVC, HIVG, HIVTM, HIVMM, HIVSS, HIVJSL, HIVEV, HIVES, and HIV13-52) (Fig. 7) were combined and propagated in a mixture of equal numbers of phytohemagglutinin (PHA)-stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (5 × 105) and MT-4 cells (5 × 105) in an attempt to adapt the mixed viral population for replication in MT-4 cells. The cell-free supernatant was harvested on day 7 of coculture (PHA-PBMCs and MT-4 cells), and the supernatant obtained was designated HIV11MIX. During the first passage, MT-4 cells (3 × 105) were exposed to HIV11MIX and cultured in the presence of each compound (GRL-079, GRL-058, DRV, and LPV) at an initial concentration equivalent to its EC50. On the last day of each passage (weeks 1 to 3), 1.5-ml aliquots of cell-free supernatant were transferred to infect fresh MT-4 cells in the presence of three drug concentrations that were 1-, 2-, and 3-fold higher than the previous concentration. When the replication of HIV-1 in the culture was confirmed by p24 Gag protein production levels of >200 ng/ml, the highest drug concentration of the three concentrations was used to continue the selection for the next round of culture. This protocol was repeated until drug concentrations reached the targeted concentration. Proviral DNA samples obtained from the lysates of infected cell cultures at selected passages were used to conduct nucleotide sequencing.

FIG 7.

Amino acid sequences of the proteases of 11 HIVMDR strains. The amino acid sequences of protease deduced from nucleotide sequences of the protease-encoding region for 11 HIVMDR strains are shown. The consensus sequence of HIV-1NL4-3 is illustrated at the top as a reference. Identity at individual amino acid positions is indicated by dots.

Determination of nucleotide sequences.

Molecular cloning and determination of nucleotide sequences of HIV-1 strains passaged in the presence of each compound were performed as previously described (19). Briefly, high-molecular-weight DNA was extracted from HIV-1-infected MT-4 cells by use of an InstaGene matrix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and then subjected to molecular cloning followed by nucleotide sequence determination. Primers used for the first round of PCR with the entire Gag- and PR-encoding regions of the HIV-1 genome were LTR F1 (5′-GAT GCT ACA TAT AAG CAG CTG C-3′) and PR12 (5′-CTC GTG ACA AAT TTC TAC TAA TGC-3′). The PCR mixture included 1 μl of proviral DNA solution, 10 μl of Premix Taq mixture (TaKaRa Ex Taq version; TaKaRa Bio Inc., Otsu, Japan), and 10 pmol of each primer in a total volume of 20 μl. The PCR conditions used were an initial 3 min at 95°C, followed by 30 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 20 s at 55°C, and 2 min at 72°C and a final 10 min of extension at 72°C. The first-round PCR products (1 μl) were used directly in the second round of PCR, using primers LTR F2 (5′-GAG ACT CTG GTA ACT AGA GAT C-3′) and Ksma2.1 (5′-CCA TCC CGG GCT TTA ATT TTA CTG GTA C-3′) and the following PCR conditions: an initial 3 min at 95°C, followed by 30 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 20 s at 55°C, and 2 min at 72°C and a final 10 min of extension at 72°C. The second-round PCR products were purified using spin columns (MicroSpin S-400 HR columns; Amersham Bioscience Corp., Piscataway, NJ), cloned directly, and subjected to sequencing using a model 3130 automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Thermal stability analysis using DSF.

A D25N substitution was introduced into PR (PRD25N) to mitigate the autoproteolytic activity of wild-type PR, thus enabling us to express, purify, and obtain PRD25N. Unfolded PRD25N in 50 mM formic acid (pH 2.8) was refolded by the addition of 100 mM ammonium acetate (pH 6.0), shifting the final pH to 5.0 to 5.2. Twenty millimolar solutions of DRV and GRL-0476, -015, -038, -058, -077, -078, and -079 in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were added to 100 mM ammonium acetate (pH 6.0) and subsequently to the formic acid-unfolded PR-containing solution, giving a final DMSO concentration of 2.5% before refolding. After centrifugation, the supernatants were collected, and Tween 20 was added to the PR-containing solution (final concentration of Tween 20, 0.005%). In the differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) analysis, the final concentration of PR mutants was 10 μM. Sypro Orange (Life Technologies) was then added to the PR solution (final concentration of Sypro Orange, 5×) (34). Thirty microliters of the PR solution was successively heated from 25 to 95°C, and the changes in fluorescence intensity were documented using a model 7500 Fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health; by grants for the promotion of AIDS research from the Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Labor of Japan; by grants from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED); by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT); by a grant from the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (NCGM) Research Institute (to H.M.); and by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM53386 to A.K.G.). This work was also supported in part by the Platform Project for Supporting Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (Platform for Drug Discovery, Informatics, and Structural Life Science), funded by MEXT and AMED.

This study utilized the high-performance computational capabilities of the Biowulf Linux cluster at the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD (https://hpc.nih.gov). Sanger sequencing was conducted at the CCR Genomics Core at the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02060-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Walensky RP, Paltiel AD, Losina E, Mercincavage LM, Schackman BR, Sax PE, Weinstein MC, Freedberg KA. 2006. The survival benefits of AIDS treatment in the United States. J Infect Dis 194:11–19. doi: 10.1086/505147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edmonds A, Yotebieng M, Lusiama J, Matumona Y, Kitetele F, Napravnik S, Cole SR, Van Rie A, Behets F. 2011. The effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on the survival of HIV-infected children in a resource-deprived setting: a cohort study. PLoS Med 8:e1001044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lohse N, Hansen AB, Gerstoft J, Obel N. 2007. Improved survival in HIV-infected persons: consequences and perspectives. J Antimicrob Chemother 60:461–463. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gomes MJ, Neves J, Sarmento B. 2014. Nanoparticle-based drug delivery to improve the efficacy of antiretroviral therapy in the central nervous system. Int J Nanomedicine (Lond) 9:1757–1769. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S45886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pantaleo G, Graziosi C, Butini L, Pizzo PA, Schnittman SM, Kotler DP, Fauci AS. 1991. Lymphoid organs function as major reservoirs for human immunodeficiency virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 88:9838–9842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brik A, Wong CH. 2003. HIV-1 protease: mechanism and drug discovery. Org Biomol Chem 1:5–14. doi: 10.1039/b208248a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurt Yilmaz NK, Swanstrom R, Schiffer CA. 2016. Improving viral protease inhibitors to counter drug resistance. Trends Microbiol 24:547–557. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitsuya H, Maeda K, Das D, Ghosh AK. 2008. Development of protease inhibitors and the fight with drug-resistant HIV-1 variants. Adv Pharmacol 56:169–197. doi: 10.1016/S1054-3589(07)56006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coffin J, Swanstrom R. 2013. HIV pathogenesis: dynamics and genetics of viral populations and infected cells. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 3:a012526. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koh Y, Nakata H, Maeda K, Ogata H, Bilcer G, Devasamudram T, Kincaid JF, Boross P, Wang YF, Tie Y, Volarath P, Gaddis L, Harrison RW, Weber IT, Ghosh AK, Mitsuya H. 2003. Novel bis-tetrahydrofuranylurethane-containing nonpeptidic protease inhibitor (PI) UIC-94017 (TMC114) with potent activity against multi-PI-resistant human immunodeficiency virus in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:3123–3129. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.10.3123-3129.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghosh AK, Kincaid JF, Cho W, Walters DE, Krishnan K, Hussain KA, Koo Y, Cho H, Rudall C, Holland L, Buthod J. 1998. Potent HIV protease inhibitors incorporating high-affinity P2-ligands and (R)-(hydroxyethylamino)sulfonamide isostere. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 8:687–690. doi: 10.1016/S0960-894X(98)00098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghosh AK, Krishnan K, Walters DE, Cho W, Cho H, Koo Y, Trevino J, Holland L, Buthod J. 1998. Structure based design: novel spirocyclic ethers as nonpeptidal P2-ligands for HIV protease inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 8:979–982. doi: 10.1016/S0960-894X(98)00139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koh Y, Amano M, Towata T, Danish M, Leshchenko-Yashchuk S, Das D, Nakayama M, Tojo Y, Ghosh AK, Mitsuya H. 2010. In vitro selection of highly darunavir-resistant and replication-competent HIV-1 variants by using a mixture of clinical HIV-1 isolates resistant to multiple conventional protease inhibitors. J Virol 84:11961–11969. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00967-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitsuya Y, Liu TF, Rhee SY, Fessel WJ, Shafer RW. 2007. Prevalence of darunavir resistance-associated mutations: patterns of occurrence and association with past treatment. J Infect Dis 196:1177–1179. doi: 10.1086/521624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sterrantino G, Zaccarelli M, Colao G, Baldanti F, Di Giambenedetto S, Carli T, Maggiolo F, Zazzi M, ARCA Database Study Group. 2012. Genotypic resistance profiles associated with virological failure to darunavir-containing regimens: a cross-sectional analysis. Infection 40:311–318. doi: 10.1007/s15010-011-0237-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delaugerre C, Mathez D, Peytavin G, Berthe H, Long K, Galperine T, de Truchis P. 2007. Key amprenavir resistance mutations counteract dramatic efficacy of darunavir in highly experienced patients. AIDS 21:1210–1213. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32810fd744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Meyer S, Lathouwers E, Dierynck I, De Paepe E, Van Baelen B, Vangeneugden T, Spinosa-Guzman S, Lefebvre E, Picchio G, de Bethune MP. 2009. Characterization of virologic failure patients on darunavir/ritonavir in treatment-experienced patients. AIDS 23:1829–1840. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832cbcec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aoki M, Hayashi H, Yedidi RS, Martyr CD, Takamatsu Y, Aoki-Ogata H, Nakamura T, Nakata H, Das D, Yamagata Y, Ghosh AK, Mitsuya H. 2015. C-5-modified tetrahydropyrano-tetrahydrofuran-derived protease inhibitors (PIs) exert potent inhibition of the replication of HIV-1 variants highly resistant to various PIs, including darunavir. J Virol 90:2180–2194. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01829-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aoki M, Venzon DJ, Koh Y, Aoki-Ogata H, Miyakawa T, Yoshimura K, Maeda K, Mitsuya H. 2009. Non-cleavage site gag mutations in amprenavir-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) predispose HIV-1 to rapid acquisition of amprenavir resistance but delay development of resistance to other protease inhibitors. J Virol 83:3059–3068. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02539-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pieniazek DRM, Hu DJ, Nkengasong JN, Soriano V, Heneine W, Zeh C, Agwale SM, Wambebe C, Odama L, Wiktor SZ. 2004. HIV-2 protease sequences of subtypes A and B harbor multiple mutations associated with protease inhibitor resistance in HIV-1. AIDS 18:495–502. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200402200-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ide K, Aoki M, Amano M, Koh Y, Yedidi RS, Das D, Leschenko S, Chapsal B, Ghosh AK, Mitsuya H. 2011. Novel HIV-1 protease inhibitors (PIs) containing a bicyclic P2 functional moiety, tetrahydropyrano-tetrahydrofuran, that are potent against multi-PI-resistant HIV-1 variants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:1717–1727. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01540-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshimura K, Kato R, Kavlick MF, Nguyen A, Maroun V, Maeda K, Hussain KA, Ghosh AK, Gulnik SV, Erickson JW, Mitsuya H. 2002. A potent human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitor, UIC-94003 (TMC-126), and selection of a novel (A28S) mutation in the protease active site. J Virol 76:1349–1358. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.3.1349-1358.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watkins T, Resch W, Irlbeck D, Swanstrom R. 2003. Selection of high-level resistance to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:759–769. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.2.759-769.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghosh AK, Martyr CD, Steffey M, Wang YF, Agniswamy J, Amano M, Weber IT, Mitsuya H. 2011. Design of substituted bis-tetrahydrofuran (bis-THF)-derived potent HIV-1 protease inhibitors, protein-ligand X-ray structure, and convenient syntheses of bis-THF and substituted bis-THF ligands. ACS Med Chem Lett 2:298–302. doi: 10.1021/ml100289m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Talele TT. 2016. The “cyclopropyl fragment” is a versatile player that frequently appears in preclinical/clinical drug molecules. J Med Chem 59:8712–8756. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aoki M, Danish ML, Aoki-Ogata H, Amano M, Ide K, Das D, Koh Y, Mitsuya H. 2012. Loss of the protease dimerization inhibition activity of tipranavir (TPV) and its association with the acquisition of resistance to TPV by HIV-1. J Virol 86:13384–13396. doi: 10.1128/JVI.07234-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gandhi RT, Wurcel A, Rosenberg ES, Johnston MN, Hellmann N, Bates M, Hirsch MS, Walker BD. 2003. Progressive reversion of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance mutations in vivo after transmission of a multiply drug-resistant virus. Clin Infect Dis 37:1693–1698. doi: 10.1086/379773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Chang YC, Louis JM, Wang YF, Harrison RW, Weber IT. 2014. Structures of darunavir-resistant HIV-1 protease mutant reveal atypical binding of darunavir to wide open flaps. ACS Chem Biol 9:1351–1358. doi: 10.1021/cb4008875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sayer JM, Liu F, Ishima R, Weber IT, Louis JM. 2008. Effect of the active site D25N mutation on the structure, stability, and ligand binding of the mature HIV-1 protease. J Biol Chem 283:13459–13470. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708506200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kohl NE, Emini EA, Schleif WA, Davis LJ, Heimbach JC, Dixon RA, Scolnick EM, Sigal IS. 1988. Active human immunodeficiency virus protease is required for viral infectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 85:4686–4690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghosh AK, Leshchenko S, Noetzel M. 2004. Stereoselective photochemical 1,3-dioxolane addition to 5-alkoxymethyl-2(5H)-furanone: synthesis of bis-tetrahydrofuranyl ligand for HIV protease inhibitor UIC-94017 (TMC-114). J Org Chem 69:7822–7829. doi: 10.1021/jo049156y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maeda K, Yoshimura K, Shibayama S, Habashita H, Tada H, Sagawa K, Miyakawa T, Aoki M, Fukushima D, Mitsuya H. 2001. Novel low molecular weight spirodiketopiperazine derivatives potently inhibit R5 HIV-1 infection through their antagonistic effects on CCR5. J Biol Chem 276:35194–35200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105670200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yedidi RS, Maeda K, Fyvie WS, Steffey M, Davis DA, Palmer I, Aoki M, Kaufman JD, Stahl SJ, Garimella H, Das D, Wingfield PT, Ghosh AK, Mitsuya H. 2013. P2′ benzene carboxylic acid moiety is associated with decrease in cellular uptake: evaluation of novel nonpeptidic HIV-1 protease inhibitors containing P2 bis-tetrahydrofuran moiety. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:4920–4927. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00868-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strisovsky K, Tessmer U, Langner J, Konvalinka J, Krausslich H. 2000. Systematic mutational analysis of the active-site threonine of HIV-1 proteinase: rethinking the “fireman's grip” hypothesis. Protein Sci 9:1631–1641. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.9.1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.