Abstract

Purpose

To develop a rapid segmentation-free method to visualize and compute wall shear stress (WSS) throughout the aorta using 4D Flow MRI data. WSS is the drag force-per-area the vessel endothelium exerts on luminal blood; abnormal levels of WSS are associated with cardiovascular pathologies. Previous methods for computing WSS are bottlenecked by labor-intensive manual segmentation of vessel boundaries. A rapid automated segmentation-free method for computing WSS is presented.

Theory and Methods

Shear stress is the dot-product of the viscous stress tensor and the inward normal vector. The inward normal vectors are approximated as the gradient of fluid speed at every voxel. Subsequently, a 4D map of shear stress is computed as the partial derivatives of velocity with respect to the inward normal vectors. We highlight the shear stress near the wall by fusing visualization with edge-emphasized anatomical data.

Results

As a proof-of-concept, four cases with aortic pathologies are presented. Visualization allows for rapid localization of pathologic WSS. Subsequent analysis of these pathological regions enables quantification of WSS. Average WSS during peak systole measures about 50–60 cPa in non-pathological regions of the aorta and is elevated in regions of stenosis, coarctation, and dissection. WSS is reduced in regions of aneurysm.

Conclusion

A volumetric technique for calculation and visualization of WSS from 4D Flow MRI data is presented. Traditional labor-intensive methods for WSS rely on explicit manual segmentation of vessel boundaries prior to visualization. This automated volumetric strategy for visualization and quantification of WSS may facilitate its clinical translation.

Keywords: Wall shear stress, Cardiovascular, Computational, 4D Flow MRI, Segmentation-Free

INTRODUCTION

Wall shear stress (WSS) is implicated in a variety of cardiovascular diseases, including atherosclerosis, aortic dissection, and aneurysm formation (1–4). While inflammation and the buildup of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol are the more commonly associated features of cardiovascular disease, pathological WSS may lie upstream of these processes (1). WSS is the drag force per area the endothelium exerts on luminal fluid and is impacted by vascular geometry, turbulent flow, and other hemodynamic disruptions. Cellular mechanotransducers may sense altered shear stress and actuate changes in vascular cell state (1). Altered WSS is associated with changes in production of vasodilatory vascular endothelial nitric oxide synthase, inflammatory processes, and endothelial structural integrity (1). It may therefore be beneficial to routinely evaluate wall shear stress in patients with cardiovascular disease.

WSS is physically defined as the change in fluid velocity at the endothelium in the direction of the vessel lumen. Computation of WSS therefore requires spatially-resolved velocity data as well as demarcation of the endothelial boundaries. 4D Flow MRI has potential for enabling non-invasive in vivo measurement of WSS, as it evaluates both blood velocity and patient anatomy. Previous work has successfully analyzed aortic WSS from 4D Flow MRI data through two approaches. In the first approach, trained observers select analysis planes along the aorta and segment each plane to explicitly demarcate the endothelium-lumen boundary. These studies then evaluate WSS by numerically approximating the change in velocity perpendicular to these boundary regions at each time point (5–12). In the second approach, trained observers employ semi-automatic segmentation packages and interpolation to generate a 3D mesh of the aorta and subsequently evaluate WSS (13–17). While these are viable methods for calculating WSS on a case-by-case basis, multiple authors note that their primary limitation is the need for user-input for manual segmentation of the aorta (5–7,13–15). Specifically, manual segmentation can lead to inter-observer variability for the lumen boundary as well as potential inaccuracies due to the spatiotemporal interpolations involved in 3D mesh generation. An additional limitation is the sheer number of segmentations required to demarcate regions-of-interest (ROI) throughout the vasculature over time; the aorta is elastic and hence its boundaries temporally, necessitating manual segmentation at every time point (15). We therefore sought to develop an approach to calculate WSS that is less dependent on user input for initial visualization. To validate our method, we compared our results to those obtained using a reference method by Potters, et al (8).

THEORY

Derivation of WSS

The viscous stress vector τ⃗ is defined by the dot product of the viscous stress tensor τ⃡ and the inward unit normal vector n⃗, pointing luminally, for a given blood fluid element (7):

| [1] |

The viscous stress tensor τ⃡ is, in turn, defined by its relationships with the strain rate tensor ε̇ of the blood fluid element and the fluid’s viscosity η:

| [2] |

We assume that in the area of interest, blood behaves as an incompressible Newtonian fluid with viscosity equal to 3.2 mPa*sec (14). Given a three-dimensional Cartesian space defined by the three axes (x1, x2, x3) and a three-dimensional velocity field (v⃗) with corresponding components (v1, v2, v3), we obtain the following strain rate tensor:

| [3] |

Since we are only concerned with the shear component of stress, we set the diagonal components to zero, as they represent orthogonal stresses. As an example, we orient our Cartesian coordinate system such that n⃗ lies on the x3 axis. We assume a no-slip boundary condition at the vessel wall boundary and negligible velocity in the direction of the normal. A restatement of these constraints is:

| [4] |

For luminal fluid elements, imposing [4] may lead to inaccuracies; however, we tolerate these potential errors for two reasons: 1) we isolate and visualize voxels with high values of shear at the vessel wall and 2) we de-emphasize and ignore voxels within the vessel lumen. As a result of these constraints, our strain rate tensor reduces to:

| [5] |

Therefore, our shear stress vector at the vessel wall is defined as:

| [6] |

Given the previously-used example coordinate system defined by the three axes (x1, x2, x3) with n⃗ lying on axis x3 as shown previously by Potters, et al. (8):

| [7] |

We can now solve for τ⃗:

| [8] |

We developed the following algorithm to extrapolate this example coordinate system and derivation to all other fluid elements.

Derivation of Algorithm

A restatement of [8] in a static Cartesian coordinate system, in which n⃗ and x2 do not necessarily align is:

| [9] |

We note that v⃗ − (v⃗ · n⃗) · n⃗ is the component of velocity parallel to the wall. To approximate the value of n⃗, we leverage the 4D flow velocity data. We assume that each blood fluid element has a velocity profile which follows the cardiac cycle and has an associated speed appreciably higher than the surrounding solid elements. That is to say, we use fluid speed as a surrogate for contrast. Therefore, we use a 3D central finite-element scheme to approximate the gradient of fluid speed (s) with second-order error:

| [10] |

| [11] |

To enhance visualization of vessel boundaries, we solve:

| [12] |

Where I is the phase contrast MRI signal intensity of a given voxel and IEdge is the value we assign for visualization of anatomical edges. We chose to define IEdge as the Hadamard product (designated by the open circle in [12]) of signal intensity and the magnitude of the gradient of speed to de-emphasize regions with large |∇|v⃗|| but low MRI signal intensity, notably the lungs.

Having calculated the value of n⃗ in [10], we can solve for the values of τ⃗ in [9] by using a 3D forward/backward finite-element scheme to approximate the gradient of velocity with second-order error. Specifically, we calculate both the forward and backward finite difference approximation of the derivative for each spatial dimension with second order error to emphasize local abrupt changes in velocity and accentuate WSS over luminal shear stress. Based on the direction of n⃗, we then set the antiparallel derivative of velocity to 0 for each spatial dimension. As we are chiefly interested in the value of shear stress at the boundary, the forward and backward difference schemes allow us to approximate the change in velocity at the boundary without erroneously using velocity values within the vessel wall, as would occur with a central difference scheme.

To enhance visualization of WSS near the wall, we solve for fluid speed and calculate the degree of alignment (parallelity) between ∇s and n⃗ and filter out luminal and extraluminal voxels away from the vessel boundary:

| [13] |

| [14] |

At the vessel wall, we assume that n⃗ points towards the center of the lumen. We also assume that fluid speed increases away from the wall as a consequence of the no-slip boundary condition; therefore, ∇s and n⃗ should generally point in the same direction (the value of [13] should be positive at the wall). Should the normal and gradient of speed vectors be anti-parallel, it is likely that the voxel in question is either a luminal element or is a computational artifact (Supporting Figure S1).

METHODS

With HIPAA-compliance and IRB approval, we retrospectively identified four 4D Flow MRI acquisitions obtained as part of clinical imaging examinations at our institution. Informed consent was waived by the local IRB. 4D Flow MRI was performed with following administration of intravenous gadolinium contrast (gadobenate dimeglumine, 0.1 mmol/kg) using a cardiac-gated, four-point encoded variable-density pseudo-randomly-ordered Cartesian sequence, followed by iterative compressed-sensing and parallel imaging reconstruction with respiratory self-navigation previously described (18, 19). MR acquisition parameters are shown in Table 1. Calculations of shear stress (τ⃗) throughout the vector field were performed in MATLAB 2016b as presented previously (20). We further optimized our methods by employing the MATLAB parallel computing toolbox. Volumetric visualization was performed using the Arterys Cardio DL 2.3 (Arterys, San Francisco, CA). For evaluation of WSS, we manually drew the ROI at the vessel-lumen interface in Arterys. We use a previously reported value of 3.2 mPa*sec for blood viscosity (14). For explicit quantification of WSS, we report two metrics, which are computed at each time step. The first metric is average WSS, which we determined by averaging the WSS within the ROI. The second metric is peak WSS, which is the maximum value of WSS detected within the ROI. The average WSS during peak systole is the maximum value of average WSS with respect to time.

Table 1.

4D Flow image acquisition parameters and acceleration factors for variable density pseudorandom undersampling are listed below, to target a scan time of approximately 12 minutes.

| Case ID | Imaging volume | Acquired resolution (mm) RL × AP × IS | Acquired matrix | Slices | velocity encoding speed (cm/s) | temporal resolution (ms) | acceleration (phase × slice) | scan time (mm:ss) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | sagittal | 3.00 × 2.50 × 1.88 | 192 × 256 (AP × IS) | 60 | 250 | 61 | 1.8 × 1.8 | 13:33 |

| 2 | coronal | 2.08 × 2.80 × 1.79 | 192 × 224 (RL × IS) | 80 | 200 | 36 | 3.2 × 1.8 | 11:28 |

| 3 | coronal | 1.88 × 2.80 × 1.41 | 192 × 256 (RL × IS) | 80 | 250 | 40 | 3.0 × 2.0 | 12:38 |

| 4 | sagittal | 3.00 × 2.38 × 1.98 | 160 × 192 (AP × IS) | 54 | 250 | 50 | 1.8 × 1.8 | 11:12 |

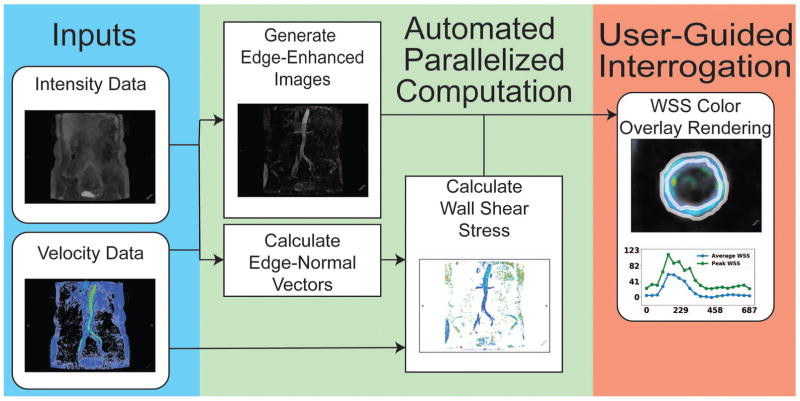

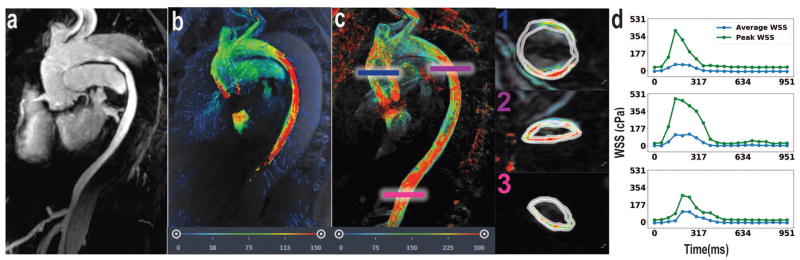

We developed a method for calculation and visualization of WSS, building on previous volumetric techniques (Figure 1) (21). Specifically, our method first assumes every voxel is at the endothelium-lumen interface and calculates an associated normal vector from velocity data. We then calculate the change in velocity along this normal vector to solve for WSS (Eq. 6). Lastly, we visualize all WSS values overlaid onto anatomical data, while preferentially suppressing intraluminal voxels (Eq. 13–14). The observer is then able to determine locally abnormal regions of WSS at-a-glance and conduct measurements as necessary. We did not perform explicit segmentation in any of the cases presented prior to quantification. In this manner, our method: 1) employs a user-independent algorithm for calculating WSS, 2) effectively calculates WSS at every voxel across space and time, and 3) enables rapid localization of regions of aberrant WSS. Finally, our method also leverages parallel computing methods to greatly reduce processing times and enable the automated calculation of WSS through a streamlined computational pipeline. The automated pipeline took approximately 30 minutes for each case to process every voxel at all time points on a 40 thread CPU system (2x Intel Xeon E5-2670v2) equipped with 132 GB RAM. Our code is available for download on GitHub at https://github.com/evmasuta/SegFreeWSS.

Figure 1.

To validate our method, we calculated WSS using a reference method (8). Specifically, we identified a planar cross-section in the vessel of interest, and created a ROI in this cross section. From this, we calculated WSS analytically from cubic-spline interpolation of the velocity field. We then compared the results from this reference method against our new approach using a two-tailed paired Student’s t-test and calculated Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

RESULTS

We evaluate our algorithm in four subjects previously referred for 4D Flow MRI to illustrate our approach. At-a-glance, it is possible to immediately see general trends of WSS throughout the aorta at every cardiac phase. Furthermore, regions of locally differing WSS are readily visible; regions of stenosis are highlighted (high WSS), whereas regions of aneurysm are de-emphasized (low WSS). Upon localizing any lesions of interest, ROIs can be drawn to quantify WSS over time. Our algorithm allows us to visualize shear stress emphasized near the wall and an experienced user can readily measure WSS at the wall itself and discriminate from artifacts.

In these four cases, we highlight anatomic detail afforded by MRA alongside 4D Flow velocity data and WSS computations. The MRA data delineates anatomic structures in finer detail. Since WSS is derived from velocity data, the 4D Flow velocity field provides a qualitative estimate for the expected WSS behavior. The following cases demonstrate agreement between our complementary datasets; we observe locally aberrant WSS in regions of gross pathology and abnormal fluid flow as evaluated by MRA and 4D Flow MRI.

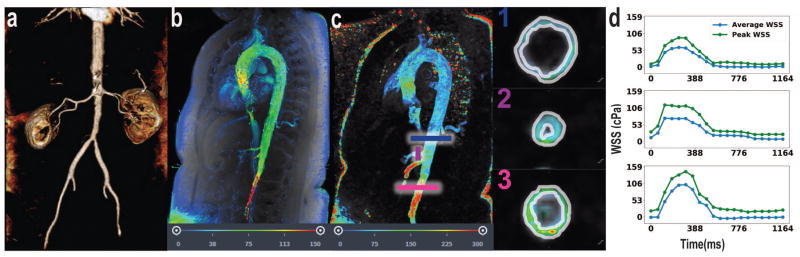

Case #1 depicts hemodynamics in a patient with presumed giant cell arteritis involving the infrarenal abdominal aorta as visualized by MRA (Figure 2a). 4D Flow MRI shows locally increased fluid velocity at the infrarenal abdominal aorta (Figure 2b). We observe elevated average WSS during peak systole (103 cPa) at the site of pathological stenosis relative average WSS during peak systole in the normal distal descending thoracic aorta (62 cPa) (Figure 2c–d). Additionally, increased WSS is present at the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries; the average WSS during peak systole in the celiac artery is 74 cPa (Figure 2d).

Figure 2.

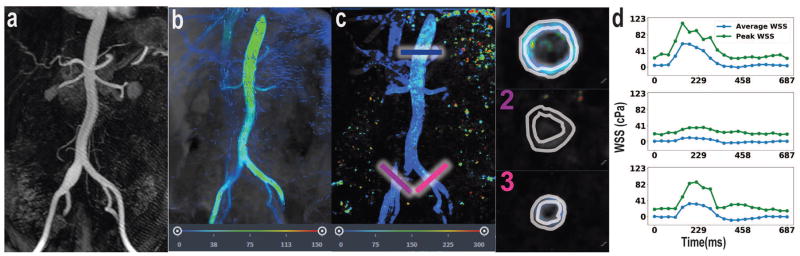

Case #2 depicts a focal right common iliac artery aneurysm as visualized by MRA (Figure 3a). 4D Flow MRI shows reduced fluid velocity in an aneurysmal right common iliac artery (Figure 3b). The normal contralateral left common iliac artery provides an internal control for WSS. This case shows the sharp disparity between average WSS during peak systole in the normal (left) common iliac artery (33 cPa) relative to the average WSS during peak systole in the aneurysmal (right) common iliac artery (10 cPa) (Figure 3c–d). Average WSS during peak systole at the distal descending thoracic aorta is consistent with case #1, at 60 cPa (figure 3d).

Figure 3.

Case #3 presents a patient with aortic coarctation with severe stenosis in the distal arch as visualized by MRA (Figure 4a). 4D Flow MRI shows increase fluid velocity at and immediately distal to the site of coarctation (Figure 4b). This case demonstrates focally elevated average WSS during peak systole at the site of stenosis (128 cPa) followed distally by a decrease in average WSS during peak systole to 30 cPa (Figure 4c–d). The calculated average WSS during peak systole in the normal ascending aorta proximal to the coarctation is consistent with the previous cases, at 49 cPa (Figure 4d).

Figure 4.

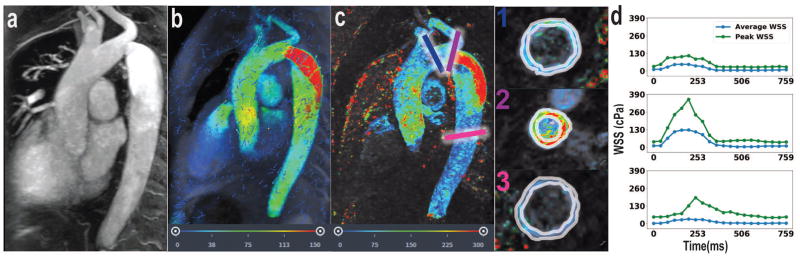

Finally, case #4 shows a patient with an aortic dissection as visualized by MRA (Figure 5a). 4D Flow MRI shows very high fluid velocity within the nearly collapsed aortic true lumen and slow flow within the larger false lumen (Figure 5b). Average WSS during peak systole is high along the course of the intimal flap both proximally (121 cPa) and distally (107 cPa) (Figure 5c–d). Proximal to the site of dissection in the normal segments of the ascending aorta, average WSS during peak systole is 65 cPa, similar to previous subjects (Figure 5d). The slow fluid flow through the false lumen generates negligible WSS.

Figure 5.

In normal aortic segments, WSS measurements appear internally consistent in this pilot population of four subjects with this approach. Average WSS during peak systole in normal aorta segments ranged from 49–65 cPa, which are similar to previously reported values obtained with other approaches (8,10,14,16,22).

When compared against a reference method, we found that our results were moderately correlated (Pearson’s r = 0.52, p = 4.4e–36) and were not statistically different (paired t-test p=0.23, 510 pairs of observations).

DISCUSSION

In this work, we derive a computationally efficient method to approximate WSS, which enables comprehensive visualization of WSS in the large vessels without need for manual contouring. Manual interaction is later leveraged to quantify WSS specifically at regions of interest, but is not required for initial visual display of WSS throughout the scanned region. This may bring greater accessibility of WSS visualization into routine clinical practice, and allow clinicians to rapidly focus analysis on regions of grossly abnormal WSS. We opted to construct our algorithm to avoid explicit hyperparameters, which enables this automated visualization.

Regions of high and low WSS may contribute to the formation and evolution of aortic dissection and aneurysm. It has been hypothesized that locally high WSS may activate WSS-dependent vasodilatory and remodeling mechanisms (1). The case of aortic coarctation presented here is suggestive that certain sections of the aortic wall may experience a greater tendency toward remodeling than others. It is worth noting that our estimates for average WSS during peak systole in non-pathological regions of the aorta are similar to “normal” values reported in the literature (approx. 60 cPa) (8,10,14,16, 22). Our method offers two main potential advantages. The first advantage, the user-independent implicit display of WSS eliminates potential mismatch between the fluid velocity boundary and user-defined boundaries for calculation of WSS.

The second advantage of our method is that for qualitative evaluation of WSS, calculations are fully-automated. Traditional methods for calculating WSS heavily rely on pre-segmentation of the vasculature; ideally, the classification of edge vs. lumen should be performed for every voxel at every time point for accurate quantification of WSS. Current methods either solely rely on manual segmentation, which comes with implicit user biases and inaccuracies, or with semi-automated methods which expedite the process by averaging frames and/or employing splines (5–17). While efficient, employment of splines is sensitive to a variety of hyperparameters such as the specific position of the nodes (8).

Our proposed algorithm relies solely on empirical data to classify voxels as edge or lumen and is therefore both user-independent and inherently reproducible. It is now possible to automatically evaluate large patient cohorts in parallel. From a clinical perspective, rapid processing of patient 4D Flow MRI data may streamline screening and diagnostics. From a research perspective, the ability to rapidly process large datasets in a reproducible manner permits the generation and evaluation of novel hypotheses correlating pathological WSS with disease states.

In addition to calculating systolic WSS where WSS is the highest, our method may be generalizable to other portions of the cardiac cycle (Supporting Video S1). However, during phases of the cardiac cycle with lower velocity, such as diastolic phases, or in vessels with complex geometry, the gradient of speed may become less reliable as an estimate of the wall normal. In situations where the vessel wall does not move or angulate considerably during the cardiac cycle, it is possible extrapolate the systolic wall normal to other cardiac phases. Evaluation and refinement of this approach is a potential subject of future investigation.

The visualization strategy we present here may depend on the quality of the underlying image data. We perform 4D Flow MRI at our institution using a post-contrast technique with compressed-sensing and modest acceleration factors to maximize image quality. It is possible that the visualization strategy presented here may not work as well with low signal-to-noise image data or in examinations performed without contrast. In addition, it is possible that with blood pool contrast agents such as ferumoxytol, that the quality of WSS calculations may further improve due to improvements in signal-to-noise. In our brief study, we did not fully examine these potential contributing factors, but can undertaken in future work.

Additionally, our study is limited by the small number of cases analyzed. For this pilot study, we were primarily interested in demonstrating a proof-of-concept and the subject of future work will be to assess large patient and control cohorts to begin construction of classifiers to differentiate between normal and pathological states. From a theoretical perspective, our method is limited by the current spatiotemporal resolution. Since the greatest change in fluid velocity occurs immediately proximal to the vessel wall, poor resolution can lead to error in the WSS approximation. It is the authors’ belief that, as measurement methods gain resolution, the results generated by our algorithm will reflect more accurately the true value of WSS.

CONCLUSION

We present a novel method to calculate and visualize WSS from 4D Flow MRI data, utilizing implicit rather than user-defined boundaries. Our method leverages parallel processing and removes the upfront need for segmentation, which may enable greater accessibility for more routine clinical use. Furthermore, our method performs comparably to a previously published reference algorithm. Our method allows for at-a-glance localization of aberrant WSS and subsequent targeted quantification. These advantages may enable greater accessibility of WSS for potential use in a clinical setting by streamlining the computational and analytical processes. Future work may include further refinement of the algorithm to account for vessel contractility (i.e. evaluating the hemodynamic effects of the radial component of fluid velocity), assessment of its sensitivity to acquired spatial resolution, and application of the technique to study WSS in specific patient populations.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Video S1: WSS visualization of case #1 (presumed giant cell arteritis) across all phases of the cardiac cycle. Scale is the same as in Fig. 2c.

Supporting Figure S1: (a) WSS visualization of case #4 (aortic dissection) with normal vector field overlaid (white arrows) prior to filtering out luminal shear voxels, (b) application of Theory equations 13 and 14 to filter out luminal shear elements to optimize visualization of shear stress near the wall.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Hsiao lab and Dr. Neil Chi for advice regarding this manuscript. We would also like to thank Travis T. Tanaka and Dr. Gerard Nihous for proofreading the theory of our work and providing helpful insights. E.M.M. is supported by the UC San Diego Medical Scientist Training Program (Grant T32GM007198). A.H. is supported by a research grant from GE Healthcare.

References

- 1.Cunningham KS, Gotlieb AI. The role of shear stress in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Lab Invest. 2005;85:9–23. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bäck M, Gasser TC, Michel JB, Caligiuri G. Biomechanical factors in the biology of aortic wall and aortic valve diseases. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;99(2):232–41. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macura KJ, Corl FM, Fishman EK, Bluemke DA. Pathogenesis in Acute Aortic Syndromes: Aortic Dissection, Intramural Hematoma, and Penetrating Atherosclerotic Aortic Ulcer. Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181(2):309–316. doi: 10.2214/ajr.181.2.1810309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cecchi E, Giglioli C, Valente S, Lazzeri C, Gensini GF, Abbate R, Mannini L. Role of hemodynamic shear stress in cardiovascular disease. Athersclerosis. 2011;214:249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harloff A, Nussbaumer A, Bauer S, Stalder AF, Frydrychowicz A, Weiller C, Hennig J, Markl M. In vivo assessment of wall shear stress in the atherosclerotic aorta using flow-sensitive 4D MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2010 Jun;63(6):1529–36. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markl M, Wallis W, Harloff A. Reproducibility of Flow and Wall Shear Stress Analysis Using Flow-Sensitive Four-Dimensional MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;33(4):988–94. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stalder AF, Russe MF, Frydrychowicz A, Bock J, Hennig J, Markl M. Quantitative 2D and 3D phase contrast MRI: Optimized analysis of blood flow and vessel wall parameters. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60(5):1218–1231. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21778. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.21778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Potters WV, van Ooij P, Marquering H, van Bavel E, Nederveen AJ. Volumetric arterial wall shear stress calculation based on cine phase contrast MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;41(2):505–516. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frydrychowicz A, Stalder AF, Russe MF, Bock J, Bauer S, Harloff A, Berger A, Langer M, Henning J, Markl M. Three-dimensional analysis of segmental wall shear stress in the aorta by flow-sensitive four-dimensional MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;30(1):77–84. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burk J, Blanke P, Stankovic Z, Barker A, Russe M, Geiger J, Frydrychowicz A, Langer M, Markl M. Evaluation of 3D blood flow patterns and wall shear stress in the normal and dilated thoracic aorta using flow-sensitive 4D CMR. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2012;14(1):84. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-14-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oyre S, Ringgaard S, Kozerke S, Paaske WP, Erlandsen M, Boesiger P, Pedersen EM. Accurate noninvasive quantitation of blood flow, cross-sectional lumen vessel area and wall shear stress by three-dimensional paraboloid modeling of magnetic resonance imaging velocity data. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32(1):128–134. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Efstathopoulos EP, Patatoukas G, Pantos I, Benekos O, Katritsis D, Kelekis NL. Wall shear stress calculation in ascending aorta using phase contrast magnetic resonance imaging. Investigating effective ways to calculate it in clinical practice. Phys Med. 2008;24:175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmp.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Ooij P, Potters WV, Collins J, Carr M, Carr J, Malaisrie SC, Fedak PWM, McCarthy PM, Markl M, Barker AJ. Characterization of Abnormal Wall Shear Stress Using 4D Flow MRI in Human Bicuspid Aortopathy. Ann Biomed Eng. 2015 Jun;43(6):1385–1397. doi: 10.1007/s10439-014-1092-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10439-014-1092-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Ooij P, Powell AL, Potters WV, Carr JC, Markl M, Barker AJ. Reproducibility and Interobserver Variability of Systolic Blood Flow Velocity and 3D Wall Shear Stress Derived From 4D Flow MRI in the Healthy Aorta. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2016;43(1):236–248. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piatti F, Sturla F, Bissell MM, Pirola S, Lombardi M, Nesteruk I, Della Corte A, Redaelli ACL, Votta E. 4D Flow Analysis of BAV-Related Fluid-Dynamic Alterations: Evidences of Wall Shear Stress Alterations in Absence of Clinically-Relevant Aortic Anatomical Remodeling. Front Physiol. 2017 Jun 26;8:441. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00441. eCollection 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bieging ET, Frydrychowicz A, Wentland A, Landgrad BR, Johnson KM, Wieben O, Francois CJ. In vivo 3-dimensional Magnetic Resonance Wall Shear Stress Estimation in Ascending Aortic Dilation. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;33(3) doi: 10.1002/jmri.22485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Renner J, Najafabadi HN, Modin D, Lanne T, Karlsson M. Subject-specific aortic wall shear stress estimations using semi-automatic segmentation. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2012;32:481–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097X.2012.01146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vasanawala SS, Hanneman K, Alley MT, Hsiao A. Congenital heart disease assessment with 4D flow MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;42(4):870–886. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng JY, Hanneman K, Zhang T, Alley MT, Lai P, Tamir JI, Uecker M, Pauly JM, Lustig M, Vasanawala SS. Comprehensive motion-compensated highly accelerated 4D flow MRI with ferumoxytol enhancement for pediatric congenital heart disease. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2016;43:1355–1368. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masutani EM, Cheng JY, Alley MT, Vasanawala SS, Hsiao A. Volumetric Segmentation-Free Method for Quantitative Visualization of Cardiovascular Wall Shear Stress Using 4D Flow MRI. Proceedings of the 25th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Honolulu, Hawaii, USA. 2017. Abstract #2846. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsiao A, Lustig M, Alley MT, Murphy MJ, Vasanawala SS. Evaluation of Valvular Insufficiency and Shunts with Parallel-imaging Compressed-sensing 4D Phase-contrast MR Imaging with Stereoscopic 3D Velocity-fusion Volume-rendered Visualization. Radiology. 2012;265(1):87–95. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sughimoto K, Shimamura Y, Tezuka C, Tsubota K, Liu H, Okumura K, Masuda Y, Haneishi H. Effects of arterial blood flow on walls of the abdominal aorta: distributions of wall shear stress and oscillatory shear index determined by phase–contrast magnetic resonance imaging. Heart Vessels. 2016;31:1168–1175. doi: 10.1007/s00380-015-0758-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Video S1: WSS visualization of case #1 (presumed giant cell arteritis) across all phases of the cardiac cycle. Scale is the same as in Fig. 2c.

Supporting Figure S1: (a) WSS visualization of case #4 (aortic dissection) with normal vector field overlaid (white arrows) prior to filtering out luminal shear voxels, (b) application of Theory equations 13 and 14 to filter out luminal shear elements to optimize visualization of shear stress near the wall.