Abstract

Liver cancer is one of the most common malignancies in the world and a leading cause of cancer-related mortality. Accumulating evidence has highlighted the critical role of long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) in various cancers. The present study aimed to explore the role of lncRNA urothelial carcinoma-associated 1 (UCA1) in cell growth and migration in MHCC97 cells and its underlying mechanism. First, we assessed the expression of UCA1 in MHCC97 and three other cell lines by RT-qPCR. Then the expression of UCA1, miR-301a, and CXCR4 in MHCC97 cells was altered by transient transfection. The effects of UCA1 and miR-301 on cell viability, migration, invasion, and apoptosis were assessed. The results revealed that UCA1 expression was relatively higher in MHCC97 cells than in MG63, hFOB1.19, and OS-732 cells. Knockdown of UCA1 reduced cell viability, inhibited migration and invasion, and promoted cell apoptosis. However, the effect of UCA1 knockdown on cell growth and migration was blocked by miR-301a overexpression, whose expression was regulated by UCA1. We also found that miR-301a positively regulated CXCR4 expression. CXCR4 inhibition reversed the effect of miR-301a overexpression on cell growth and migration. Moreover, miR-301a activated the Wnt/β-catenin and NF-κB pathways via regulating CXCR4. The present study demonstrated that UCA1 inhibition exerted an antigrowth and antimigration role in MHCC97 cells through regulating miR-301a and CXCR4 expression.

Key words: Urothelial carcinoma-associated 1 (UCA1), MicroRNA-301a, CXCR4, Cell apoptosis, Migration and invasion, Liver cancer

INTRODUCTION

Liver cancer is one of the most common malignancies in the world and is a leading cause of cancer-related mortality1. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represents a major global health problem, since it accounts for 70%–90% of all primary liver cancers worldwide2. Epidemiologic evidence demonstrates that even though HCC primarily occurs in Asia and Africa, the medical and economic burden of HCC will still soar drastically in Western populations during the next decade3. Thus, exploration of the underlying mechanisms of liver carcinogenesis is urgently needed, as well as the development of novel diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic strategies for patients with HCC.

Recently, increasing evidence has highlighted the role of a group of long non-protein-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) in carcinogenesis, and it has been suggested that lncRNAs could be considered as biomarkers in various cancers4–6. lncRNAs, a class of non-protein-coding RNAs longer than 200 bp in length, have been reported to play a crucial role in the process of cancer, including cell proliferation, cell apoptosis, metastasis, and differentiation7–10. Several lncRNAs have been reported to be involved with the development and progress of HCC. For instance, lncRNA LINC00152 has been demonstrated to be upregulated in HCC tissues and HCC cell lines, and promoted cell proliferation in HCC by targeting EpCAM via the mTOR signaling pathway11. Another lncRNA, highly upregulated in liver cancer (HULC), enhances epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) to promote tumorigenesis and metastasis of HCC via regulating the microRNA 200a-3p (miR-200a-3p)/ZEB1 signaling pathway12. Human urothelial carcinoma-associated 1 (UCA1) gene is located in chromosome 19p13.12, which has three exons and encodes two transcripts13. Several studies have revealed that UCA1 is highly expressed in various cancers, such as bladder cancer, breast cancer, and colorectal cancer, and it promotes tumor growth and invasion13–16. However, the role of UCA1 in HCC and its underlying molecular mechanisms are not fully elucidated.

The present study aimed to explore the role of UCA1 in the growth and metastasis of HCC cell lines and its underlying mechanism. We found that the expression of UCA1 was relatively higher in MHCC97 cells, and inhibition of UCA1 reduced cell viability, inhibited cell migration and invasion, and promoted cell apoptosis in MHCC97 cells. Moreover, we found that UCA1 inhibition might exert its antigrowth and antimigration role via regulating miR-301a and C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture and Treatment

Human liver cancer cell line MHCC97 and human osteosarcoma cell lines (MG63, hFOB1.19, and OS-732) were all obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Rockville, MD, USA). Cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; HyClone, Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD, USA), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Life Technologies Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and were incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2.

Transfection and Generation of Stably Transfected Cell Lines

Short hairpin RNA (shRNA) directed against human lncRNA UCA1 and CXCR4 was ligated into the U6/GFP/Neo plasmids (GenePharma, Shanghai, P.R. China) and were referred to as sh-UCA1 and sh-CXCR4. The plasmid PGPU6/GFP/neo-shControl (GenePharma) encoded with a nonsense sequence was used as the negative control (NC) of sh-UCA1 and sh-CXCR4 and were referred to as shNC and sh-NC, respectively. Meanwhile, the full-length CXCR4 sequence directed against CXCR4 was subcloned into the pEX-2 plasmid (GenePharma) and was referred to as pEX-CXCR4. Empty pEX-2 plasmid acted as an NC of pEX-CXCR4 and was referred to as pEX. The Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (Life Technologies Corporation) was used for the cell transfection following the manufacturer’s instructions. miR-301a inhibitor, miR-301a mimic, and their corresponding NCs (inhibitor control and mimic control) were synthesized by GenePharma and were transfected into MHCC97 cells with Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (Life Technologies Corporation).

Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cells using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies Corporation) under the manufacturer’s instructions. The One-Step SYBR® PrimeScript® PLUS RT-RNA PCR Kit (TaKaRa Biotechnology, Dalian, P.R. China) was used for the RT-qPCR analysis to detect the expression levels of UCA1. The TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit and TaqMan Universal Master Mix II with the TaqMan MicroRNA Assay of miR-301a and U6 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) were used for evaluating the expression levels of miR-301a. Expression level of CXCR4 was detected using the RNA PCR Kit (AMV) Ver.3.0 (TaKaRa Biotechnology) for transcription and SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ II (TaKaRa Biotechnology) for qPCR. GAPDH and U6 were used for the normalization of mRNA and lncRNA or miRNA, respectively. The results were presented as fold changes relative to U6 or GAPDH and were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Cell Viability Assay

Cell viability was determined by trypan blue exclusion assay. Briefly, 1 × 105 cells were seeded in 60-mm dishes and cultured for 48 h. Then cells were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the number of viable cells was determined by trypan blue exclusion (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, P.R. China) as previously described17.

Migration and Invasion Assay

Cell migration was determined using a modified two-chamber migration assay with a pore size of 8 μm. For the migration assay, 1 × 105 cells in 0.2 ml of serum-free medium were plated on the upper compartment of a 24-well Transwell culture chamber (Corning, Lowell, MA, USA), and the lower chamber was filled with 0.6 ml of medium containing 10% FBS. For the invasion assay, 1.5 × 105 cells were plated on the upper chamber precoated with 20 μg of Matrigel (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA, USA). After incubation for 48 h, the migrated and invaded cells in the lower chamber were fixed with 100% methanol and stained with 0.1% crystal violet (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The cells that did not migrate or invade through the pores were removed by cotton swabs. The migrated and invaded cells were counted in five random fields and expressed as the average number of cells per field. These experiments were done in triplicate and performed a minimum of three times.

Apoptosis Assay

The apoptotic cell rates were determined using an Annexin-V-Phycoerythrin (PE) Apoptosis Detection Kit (Beyotime Biotechnology). Briefly, the cells were harvested and washed with PBS three times. Then cells were resuspended with 500 μl of 1× binding buffer and were stained with 5 μl of annexin V-PE for 15 min in the dark at 37°C. Cell apoptosis was measured using a FACScan (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA), and the data were analyzed utilizing FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR, USA).

Western Blot Assay

The proteins used for Western blot were extracted using radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (Beyotime Biotechnology), supplemented with protease inhibitors (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). The BCA™ Protein Assay Kit (Pierce, Appleton, WI, USA) was used to quantify the concentration of proteins. Then 30 μg of protein was loaded and separated with a Bio-Rad Bis-Tris Gel system based on the manufacturer’s instructions. All the blots were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Roche) for 2 h at room temperature. Subsequently, the blots were incubated with primary antibodies against Bcl-2 (#4223), Bax (#5023), caspase 3 (#9662), caspase 9 (#9502), GAPDH (#2118), p-p65 (#3033), p65 (#8242), IκBα (#4812), p-IκBα (#2859) (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA), Wnt3a (ab28472), Wnt5a (ab72583), CXCR4 (ab197203), and β-catenin (ab6302) (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) overnight at 4°C. Then the blots were rinsed with TBST three times, followed by incubation with secondary antibody labeled with horseradish peroxidase for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes carrying blots and antibodies were placed in the ChemiDoc™ XRS system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), and 200 μl of Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Millipore) was added to cover the membrane surface. The signals were captured and analyzed using Image Lab™ software (Bio-Rad).

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were repeated three times. The results of multiple experiments are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). The p values were calculated using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). A value of p < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant result.

RESULTS

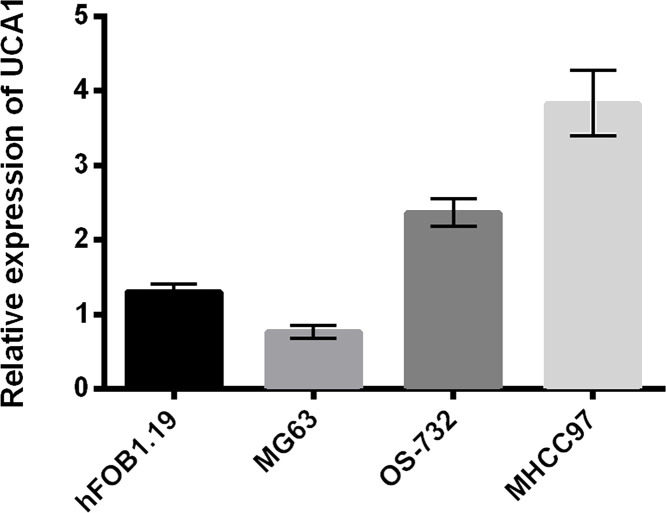

UCA1 Was Highly Expressed in MHCC97 Cells

We first detected the expression of UCA1 in the human liver cancer cell line MHCC97 and three other cell lines. As shown in Figure 1, the expression of UCA1 was highest in MHCC97 cells compared with the other three cell lines, human osteosarcoma MG63 and OS-732, and human osteoblast cell line hFOB1.19.

Figure 1.

Urothelial carcinoma-associated 1 (UCA1) was highly expressed in MHCC97 cells. The expression of UCA1 in MHCC97, MG63, hFOB1.19, and OS-732 cells was measured by quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis.

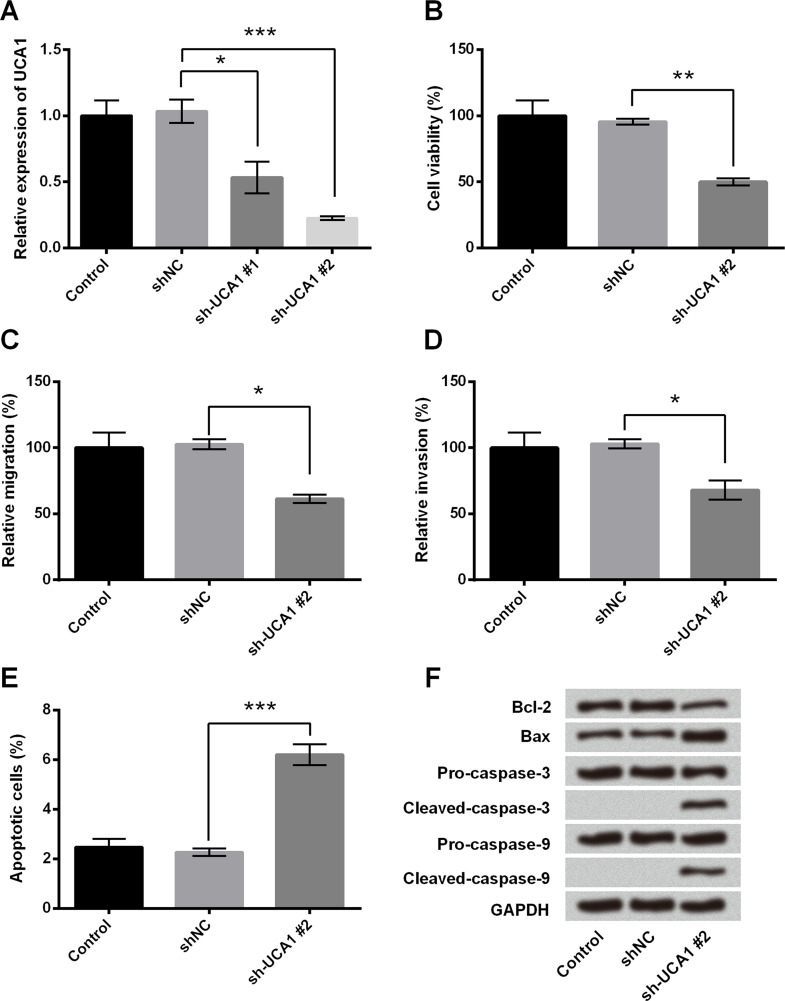

Knockdown of UCA1 Inhibited Cell Growth and Migration in MHCC97 Cells

We then investigated the role of UCA1 in cell viability, migration, invasion, and apoptosis in MHCC97 cells. The expression of UCA1 was inhibited by transfection with sh-UCA1. The efficiency of transfection was identified by RT-qPCR. As shown in Figure 2A, the level of UCA1 was significantly reduced in MHCC97 cells transfected with sh-UCA1#1 and sh-UCA1#2, and the transfected efficiency of sh-UCA1#2 was higher than that of sh-UCA1#1 (p < 0.05 or p < 0.001). Thus, we selected sh-UCA1#2 for the suppression of UCA1 in the following experiments. Cell viability was significantly reduced in MHCC97 cells after transfection with sh-UCA1#2 (p < 0.01) (Fig. 2B). Meanwhile, knockdown of UCA1 reduced cell migration and invasion (Fig. 2C and D) (p < 0.05). We also found that knockdown of UCA1 promoted cell apoptosis in MHCC97 cells, as evidenced by increasing the percentage of apoptotic cells (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2E), as well as inducing the expression of the proapoptosis factors (Bax, cleaved caspase 3, and cleaved caspase 9) and reducing the Bcl-2 expression (Fig. 2F). Overall, these results revealed that knockdown of UCA1 suppressed cell growth and migration in MHCC97 cells.

Figure 2.

Knockdown of UCA1 inhibited cell growth and migration in MHCC97 cells. MHCC97 cells were transfected with shNC, sh-UCA1#1, and sh-UCA1#2. (A) The efficiency of transfection was quantified by RT-qPCR analysis. (B) Cell viability was measured by trypan blue exclusion assay. (C) Cell migration and (D) invasion were detected by Transwell migration assay. (E) Apoptotic cells and (F) the levels of apoptosis-related proteins were measured by flow cytometry and Western blot, respectively. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

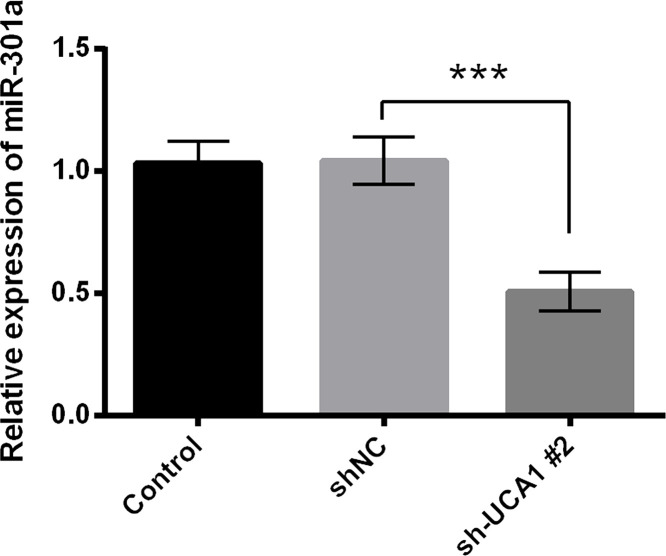

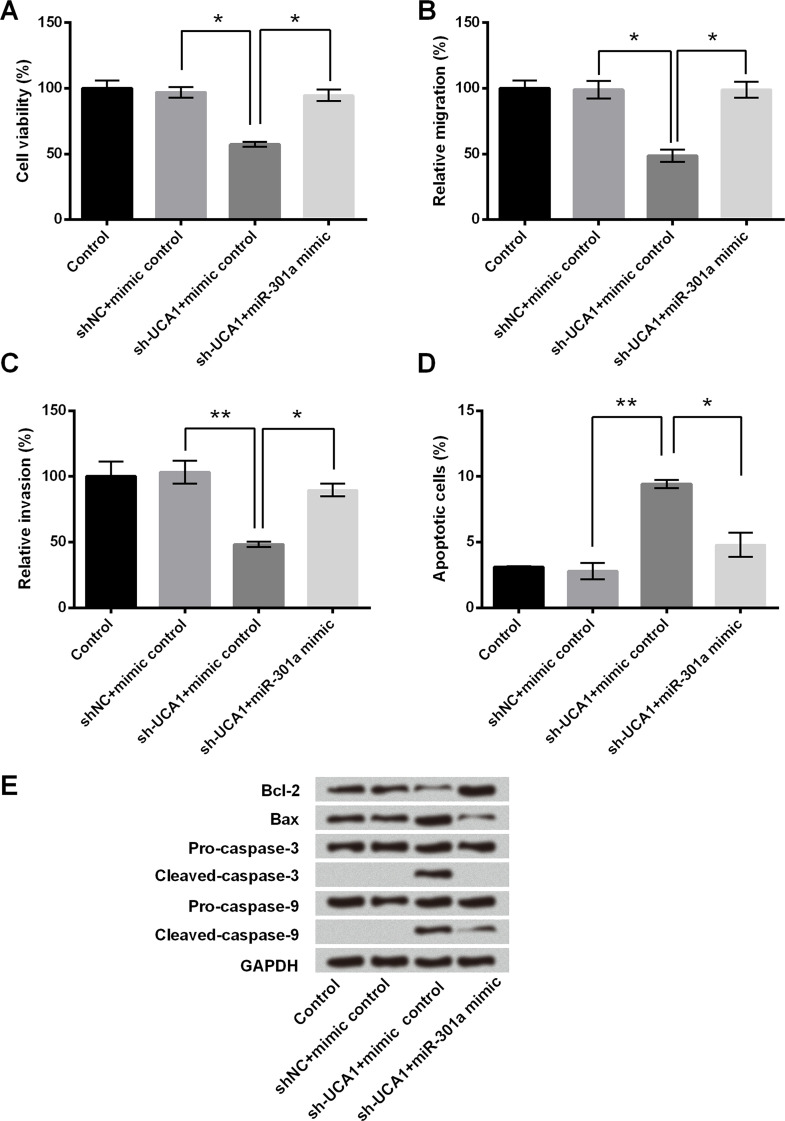

miR-301a Overexpression Blocked the Effect of UCA1 on Cell Growth and Migration in MHCC97 Cells

The RT-qPCR analysis showed that the expression of miR-301a was remarkably decreased in sh-UCA1-transfected cells compared with the corresponding controls (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3). Then we further investigated the role of miR-301a in the modulation of UCA1 knockdown in cell growth and migration. As shown in Figure 4A, miR-301a overexpression inhibited the cell viability reduction caused by sh-UCA1 transfection (p < 0.05). Consistently, miR-301a overexpression increased cell migration and invasion even though the cells were transfected with sh-UCA1 (p < 0.05 or p < 0.01) (Fig. 4B and C). The results of the flow cytometry and Western blot showed that miR-301a overexpression reversed the promoting effect of sh-UCA1 on cell apoptosis, in that the apoptotic cell rate was reduced and the expression of proapoptotic proteins was inhibited, while antiapoptotic protein expression was elevated (p < 0.05 or p < 0.01) (Fig. 4D and E). These results suggested that the modulation of UCA1 inhibition on cell growth and migration was associated with the downregulation of miR-301a.

Figure 3.

The expression of miR-301a was downregulated by UCA1 inhibition. MHCC97 cells were transfected with shNC and sh-UCA1#2. The expression of miR-301a was detected by RT-qPCR analysis. ***p < 0.001.

Figure 4.

miR-301a overexpression blocked the effect of UCA1 on cell growth and migration in MHCC97 cells. MHCC97 cells were transfected with sh-UCA1 or shNC, or cotransfected with sh-UCA1 and miR-301a mimic or mimic control. (A) Cell viability, (B) cell migration, and (C) invasion were assessed by trypan blue exclusion assay and Transwell migration assay, respectively. (D) Apoptotic cells were quantified by flow cytometry assay. (E) Western blot was conducted to measure the expression of apoptosis-related core factors. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

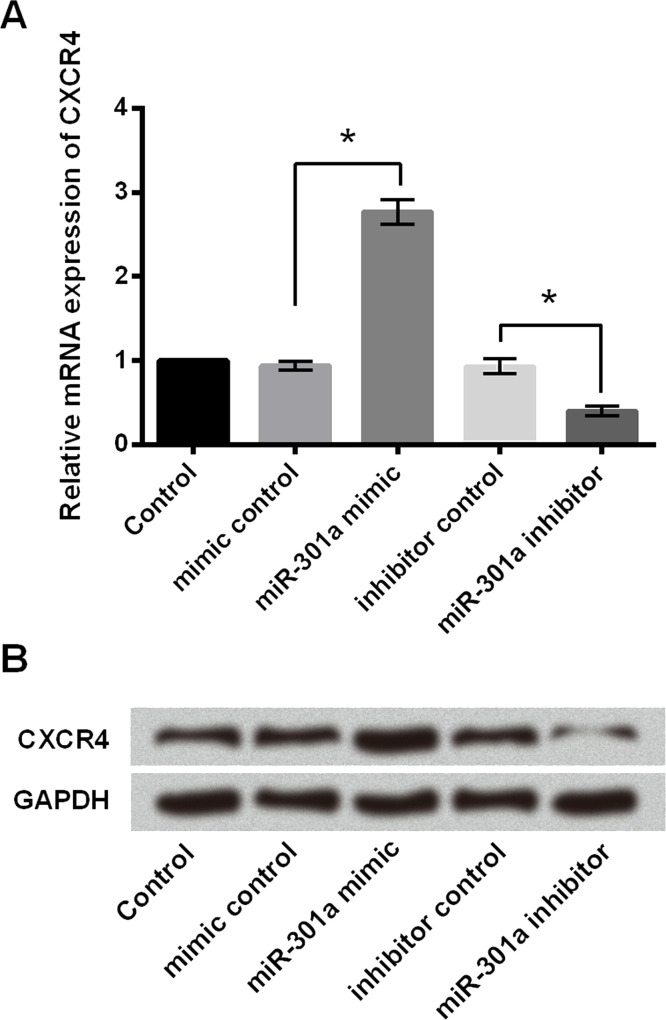

The Expression of CXCR4 Was Positively Regulated by miR-301a

As shown in Figure 5A, the mRNA expression of CXCR4 was upregulated by miR-301a mimic, while it was downregulated by a miR-301a inhibitor (p < 0.05). Similar results were observed in protein levels by Western blot analysis (Fig. 5B). These results showed that miR-301a positively regulated the expression of CXCR4 in MHCC97 cells.

Figure 5.

The expression of C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4) was positively regulated by miR-301a. miR-301a mimic, miR-301a inhibitor, or their corresponding controls (mimic control and inhibitor control) were transfected into MHCC97 cells. (A) The mRNA and (B) protein expression of CXCR4 was determined by RT-qPCR analysis and Western blot analysis, respectively. *p < 0.05.

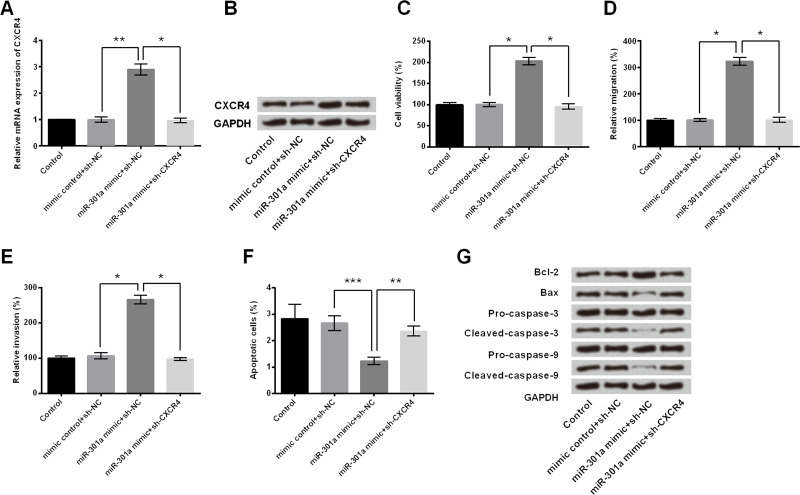

CXCR4 Was Involved in the Regulatory Effect of miR-301a on Cell Growth and Migration

Since we found that CXCR4 expression was regulated by miR-301a, we further explored whether CXCR4 participated in the modulation of miR-301a on cell growth and migration of MHCC97 cells. MHCC97 cells were transfected with miR-301a or cotransfected with sh-CXCR4. As shown in Figure 6A and B, the mRNA and protein expressions of CXCR4 were upregulated by miR-301a mimic (p < 0.01). However, this modulation was reversed by sh-CXCR4 transfection (p < 0.05), which further confirmed the regulatory relationship between CXCR4 and miR-301a. Interestingly, we found that the progrowth and promigration effect of miR-301a mimic was reversed by sh-CXCR4, as demonstrated by declining cell viability (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6C) and inhibition of cell migration and invasion (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6D and E), reducing apoptotic cell rate (p < 0.01 or p < 0.001) (Fig. 6F) as well as regulating the protein expression of apoptosis-related core factors (Fig. 6G). From the above, it indicated that miR-301a overexpression enhanced cell growth and migration through upregulation of CXCR4 expression.

Figure 6.

CXCR4 was involved in the regulatory effect of miR-301a on cell growth and migration. MHCC97 cells were transfected with sh-CXCR4 or sh-NC, or cotransfected with sh-CXCR4 and miR-301a mimic, or mimic control. The (A) mRNA and (B) protein expression levels of CXCR4 were tested by RT-qPCR analysis and Western blot analysis, respectively. (C) Cell viability, (D) cell migration, (E) invasion, and (F) apoptotic cells were assessed by trypan blue exclusion assay, Transwell migration assay, and flow cytometry assay, respectively. (G) The protein levels of apoptosis-related factors were measured by Western blot. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

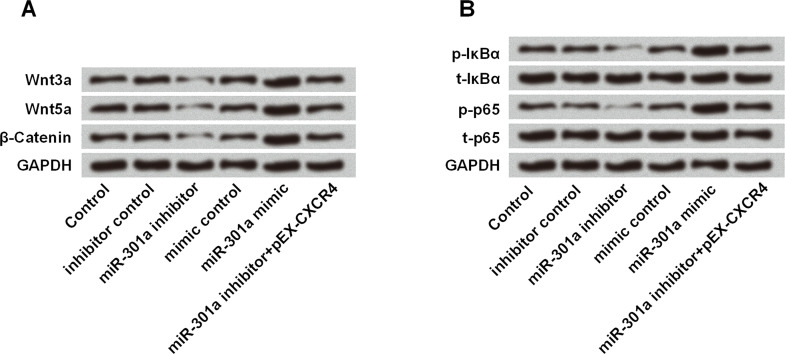

miR-301a Enhanced the Activation of the Wnt/β-Catenin and NF-κB Signaling Pathway Through Upregulating CXCR4

Results in Figure 7A showed that miR-301a inhibitor suppressed the expressions of Wnt3a, Wnt5a, and β-catenin, while miR-301a mimic acted as an opposite regulatory effect. However, the inhibitive effect of the miR-301a inhibitor was blocked by CXCR4 overexpression, as pEX-CXCR4 increased the expression of the three proteins related with the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Similar regulation was found in the NF-κB signaling pathway in that the pathway was activated by miR-301a mimic while suppressed by miR-301a inhibitor. Results in Figure 7B revealed that miR-301a inhibitor suppressed the phosphorylation of IκBα and p65, and miR-301a mimic accelerated the expression of p-IκBα and p-p65. Furthermore, overexpression of CXCR4 blocked the suppressive influence on the NF-κB signaling pathway. In general, these results suggested that miR-301a enhanced the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin and NF-κB signaling pathways through upregulating CXCR4.

Figure 7.

miR-301a enhanced the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin and NF-κB signaling pathways through upregulating CXCR4. MHCC97 cells were transfected with miR-301a inhibitor, miR-301a mimic, or their corresponding controls (mimic control and inhibitor control), or cotransfected with miR-301a inhibitor and pEX-CXCR4. The protein expression of (A) Wnt/β-catenin- and (B) NF-κB signaling pathway-related core factors was measured by Western blot.

DISCUSSION

An increasing number of studies reveal that the aberrant expression of lncRNAs is highly involved with the progression and prognosis of cancers, serving a role as either an oncogene or a tumor suppressor gene18–21. Thus, it will be beneficial and meaningful to deeply clarify the biological and molecular mechanisms of lncRNAs in cancer. The expression of UCA1 has been reported to be highly expressed in various cancers, and it may serve the role of an oncogene13–16. In our present study, we found that lncRNA UCA1 was relatively expressed higher in the human liver cancer cell line (MHCC97 cells) compared with three human osteosarcoma or osteoblast cell lines (MG63, OS-732, and hFOB1.19). Downregulation of UCA1 decreased cell viability, inhibited cell migration, and induced cell apoptosis of MHCC97 cells. Our results were consistent with a previous study in which the expression of UCA1 is aberrantly upregulated in HCC tissues, and UCA1 depletion inhibited the growth and metastasis of HCC cell lines in vitro and in vivo22.

Even though the role of UCA1 in HCC has been reported previously in one study, it still remains significant to explore the underlying mechanism(s) for us to better understand the pathogenesis of HCC. A previous study highlighted that UCA1 contributed to the progression of HCC via directly downregulating miR-216b expression and promoting the activation of the FGFR1/ERK signaling pathway22. However, our study revealed that knockdown of UCA1 exerted its antigrowth and antimigration roles through downregulation of miR-301a and CXCR4, which is also involved in the inactivation of the Wnt/β-catenin and NF-κB signaling pathways. miR-301a, located in the human chromosome 17q22-17q23, has been previously reported to be overexpressed in many kinds of human cancers and shown to be an oncogene in gastric cancer23, pancreatic cancer24, liver cancer25, and colorectal cancer26. In HCC, miR-301a was significantly upregulated, and inhibition of miR-301a suppressed HepG2 cell growth, migration, and invasion, and induced cell apoptosis through targeting homeobox gene Gax and then modulating NF-κB expression25. In the present study, we found that miR-301a was downregulated by UCA1 knockdown. Furthermore, miR-301a overexpression reversed the inhibitory effect of UCA1 knockdown on cell growth and migration, which is consistent with the previous study. However, the relationship between miR-301a and UCA1 and the underlying regulatory mechanisms need to be further explored in our future studies.

CXCR4, the receptor for stromal cell-derived factor (SDF-1), plays an important role in angiogenesis and is associated with tumor progression27,28. CXCR4 has been indicated as a critical factor for breast cancer metastasis through the interaction with SDF-129. Inhibition of CXCR4 by siRNA impairs the invasion of breast cancer cells in the Matrigel invasion assay and inhibits breast cancer metastasis in an animal model30. Meanwhile, it has been reported that CXCR4 promotes the EMT process and progression of colorectal cancer31. Furthermore, CXCR4 acts in colorectal cancer EMT and progression through the regulation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway31. In the theoretical sense, miRNAs are involved in the mediation of gene expression via targeting their binding sites, usually in the 3′-UTR of mRNA, and this leads to posttranscriptional or translational repression32. However, a recent study demonstrated that miRNA positively regulated the expression of downstream mRNA, due to its being complementary to the promoter sequences of specific genes33. Qu et al. reported that miR-558 was upregulated and positively correlated with HPSE expression in neuroblastoma tissues and cell lines, as well as directly targeted the HPSE promoter to activate its transcription34. Similar with this study, our results suggested that the expression of CXCR4 was positively regulated by miR-301a. This might be because miR-301a upregulated the expression of CXCR4 through directly targeting the CXCR4 promoter. However, studies are still needed to clarify this hypothesis and further explore the relationship between miR-301a and CXCR4 in the future. In addition, we found that CXCR4 inhibition blocked the effect of miR-301a overexpression on cell viability, migration, invasion, and apoptosis, which suggested that inhibition of CXCR4 might exert antigrowth and antimetastasis effects on MHCC97 cells.

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway plays critical roles in cell proliferation, differentiation, and adhesion35,36. It has been demonstrated that CXCR4 promotes tumor progression by activating the canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in pancreatic cancer and colorectal cancer31,37. Furthermore, a previous study showed that upregulated miR-301a in breast cancer promoted tumor metastasis by targeting PTEN and activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling38. Similarly, the NF-κB pathway has been reported to be regulated by CRCX439 and miR-301a40. Thus, we hypothesized that miR-301a may regulate the activation of Wnt/β-catenin and NF-κB signaling in liver cancer cells through CXCR4. We found that miR-301a mimic enhanced the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin and NF-κB signaling pathways, while miR-301a inhibitor exerted the opposite effect. Moreover, CXCR4 inhibition reversed the regulatory effect of miR-301a on these signaling pathways. It suggested that miR-301a might activate the Wnt/β-catenin and NF-κB signaling pathways through the regulation of CXCR4.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that UCA1 was highly expressed in MHCC97 cells. Knockdown of UCA1 inhibited cell viability, migration, and invasion, and promoted cell apoptosis in MHCC97 cells through the regulation of miR-301a and CXCR4. Our study might help us better understand the progression of HCC and shed new light on the diagnosis and treatment for HCC.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by the 2017 Zhuhai Science and Technology Project (20171009E030026).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wray CJ, Harvin JA, Silberfein EJ, Ko TC, Kao LS. Pilot prognostic model of extremely poor survival among high-risk hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Cancer 2012;118(24):6118–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yeh YT, Chang CW, Wei RJ, Wang SN. Progesterone and related compounds in hepatocellular carcinoma: Basic and clinical aspects. BioMed Res Int. 2013;2013(12):290575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dhanasekaran R, Limaye A, Cabrera R. Hepatocellular carcinoma: Current trends in worldwide epidemiology, risk factors, diagnosis, and therapeutics. Hepat Med. 2012;4:19–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yarmishyn AA, Kurochkin IV. Long noncoding RNAs: A potential novel class of cancer biomarkers. Front Genet. 2015;6:145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhou M, Wang X, Shi H, Cheng L, Wang Z, Zhao H, Yang L, Sun J. Characterization of long non-coding RNA-associated ceRNA network to reveal potential prognostic lncRNA biomarkers in human ovarian cancer. Oncotarget 2016;7(11):12598–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang K, Luo Z, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Wu L, Liu L, Yang J, Song X, Liu J. Circulating lncRNA H19 in plasma as a novel biomarker for breast cancer. Cancer Biomark. 2016;17(2):187–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pickard MR, Williams GT. The hormone response element mimic sequence of GAS5 lncRNA is sufficient to induce apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Oncotarget 2016;7(9):10104–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arase M, Horiguchi K, Ehata S, Morikawa M, Tsutsumi S, Aburatani H, Miyazono K, Koinuma D. Transforming growth factor-β-induced lncRNA-Smad7 inhibits apoptosis of mouse breast cancer JygMC(A) cells. Cancer Sci. 2014;105(8):974–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jia X, Wang Z, Qiu L, Yang Y, Wang Y, Chen Z, Liu Z, Yu L. Upregulation of LncRNA-HIT promotes migration and invasion of non-small cell lung cancer cells by association with ZEB1. Cancer Med. 2016;5(12):3555–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhou X, Ye F, Yin C, Zhuang Y, Yue G, Zhang G. The interaction between miR-141 and lncRNA-H19 in regulating cell proliferation and migration in gastric cancer. Cellular Physiol Biochem. 2015;36(4):1440–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jie J, Tang J, Lei D, Yu X, Jiang R, Li G, Sun B. LINC00152 promotes proliferation in hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting EpCAM via the mTOR signaling pathway. Oncotarget 2015;6(40):42813–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li SP, Xu HX, Yu Y, He JD, Wang Z, Xu YJ, Wang CY, Zhang HM, Zhang RX, Zhang JJ. LncRNA HULC enhances epithelial-mesenchymal transition to promote tumorigenesis and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma via the miR-200a-3p/ZEB1 signaling pathway. Oncotarget 2016;7(27):42431–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huang J, Zhou N, Watabe K, Lu Z, Wu F, Xu M, Mo YY. Long non-coding RNA UCA1 promotes breast tumor growth by suppression of p27 (Kip1). Cell Death Dis. 2014;5(1):e1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang Y, Chen W, Yang C, Wu W, Wu S, Qin X, Li X. Long non-coding RNA UCA1a(CUDR) promotes proliferation and tumorigenesis of bladder cancer. Int J Oncol. 2012;41(1):276–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang F, Li X, Xie XJ, Zhao L, Chen W. UCA1, a non-protein-coding RNA up-regulated in bladder carcinoma and embryo, influencing cell growth and promoting invasion. FEBS Lett. 2008;582(13):1919–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Han Y, Yang YN, Yuan HH, Zhang TT, Sui H, Wei XL, Liu L, Huang P, Zhang WJ, Bai YX. UCA1, a long non-coding RNA up-regulated in colorectal cancer influences cell proliferation, apoptosis and cell cycle distribution. Pathology 2014;46(5):396–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hsieh TC, Wijeratne EK, Liang JY, Gunatilaka AL, Wu JM. Differential control of growth, cell cycle progression, and expression of NF-kappaB in human breast cancer cells MCF-7, MCF-10A, and MDA-MB-231 by ponicidin and oridonin, diterpenoids from the Chinese herb Rabdosia rubescens. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;337(1):224–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cui Z, Ren S, Lu J, Wang F, Xu W, Sun Y, Wei M, Chen J, Gao X, Xu C. The prostate cancer-up-regulated long noncoding RNA PlncRNA-1 modulates apoptosis and proliferation through reciprocal regulation of androgen receptor. Urol Oncol. 2013;31(7):1117–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li H, Yu B, Li J, Su L, Yan M, Zhu Z, Liu B. Overexpression of lncRNA H19 enhances carcinogenesis and metastasis of gastric cancer. Oncotarget 2014;5(8):2318–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yang G, Lu X, Yuan L. LncRNA: A link between RNA and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014;1839(11):1097–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zheng HT, Shi DB, Wang YW, Li XX, Xu Y, Tripathi P, Gu WL, Cai GX, Cai SJ. High expression of lncRNA MALAT1 suggests a biomarker of poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7(6):3174–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang F, Ying HQ, He BS, Pan YQ, Deng QW, Sun HL, Chen J, Liu X, Wang SK. Upregulated lncRNA-UCA1 contributes to progression of hepatocellular carcinoma through inhibition of miR-216b and activation of FGFR1/ERK signaling pathway. Oncotarget 2015;6(10):7899–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang M, Li C, Yu B, Su L, Li J, Ju J, Yu Y, Gu Q, Zhu Z, Liu B. Overexpressed miR-301a promotes cell proliferation and invasion by targeting RUNX3 in gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48(9):1023–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen Z, Chen LY, Dai HY, Wang P, Gao S, Wang K. miR-301a promotes pancreatic cancer cell proliferation by directly inhibiting Bim expression. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113(10):3229–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhou P, Jiang W, Wu L, Chang R, Wu K, Wang Z. miR-301a is a candidate oncogene that targets the homeobox gene Gax in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57(5):1171–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang W, Tao Z, Jin R, Zhao H, Jin H, Bo F, Lu Z, Zheng M, Wang M. MicroRNA-301a promotes migration and invasion by targeting TGFBR2 in human colorectal cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2014;33(1):113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Burger JA, Kipps TJ. CXCR4: A key receptor in the crosstalk between tumor cells and their microenvironment. Blood 2006;107(5):1761–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang YC, Hu XB, He F, Feng F, Wang L, Li W, Zhang P, Li D, Jia ZS, Liang YM. Lipopolysaccharide-induced maturation of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells is regulated by notch signaling through the up-regulation of CXCR4. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(23):15993–6003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Müller A, Homey B, Soto H, Ge N, Catron D, Buchanan ME, Mcclanahan T, Murphy E, Yuan W, Wagner SN. Involvement of chemokine receptors in breast cancer metastasis. Nature 2001;410(6824):50–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liang Z, Yoon Y, Votaw J, Goodman MM, Williams L, Shim H. Silencing of CXCR4 blocks breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 2005;65(3):967–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hu TH, Yao Y, Yu S, Han LL, Wang WJ, Guo H, Tian T, Ruan ZP, Kang XM, Wang J. SDF-1/CXCR4 promotes epithelial–mesenchymal transition and progression of colorectal cancer by activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Cancer Lett. 2014;354(2):417–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Haas U, Sczakiel G, Laufer S. MicroRNA-mediated regulation of gene expression is affected by disease-associated SNPs within the 3′-UTR via altered RNA structure. RNA Biol. 2012;9(6):924–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Place RF, Li LC, Pookot D, Noonan EJ, Dahiya R. MicroRNA-373 induces expression of genes with complementary promoter sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008;105(5):1608–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Qu H, Zheng L, Pu J, Mei H, Xiang X, Zhao X, Li D, Li S, Mao L, Huang K. miRNA-558 promotes tumorigenesis and aggressiveness of neuroblastoma cells through activating the transcription of heparanase. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24(9):2539–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brabletz T, Jung A, Dag S, Hlubek F, Kirchner T. beta-catenin regulates the expression of the matrix metalloproteinase-7 in human colorectal cancer. Am J Pathol. 1999;155(4):1033–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wielenga VJ, Smits R, Korinek V, Smit L, Kielman M, Fodde R, Clevers H, Pals ST. Expression of CD44 in Apc and Tcf mutant mice implies regulation by the WNT pathway. Am J Pathol. 1999;154(2):515–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang Z, Ma Q, Liu Q, Yu H, Zhao L, Shen S, Yao J. Blockade of SDF-1/CXCR4 signalling inhibits pancreatic cancer progression in vitro via inactivation of canonical Wnt pathway. Br J Cancer 2008;99(10):1695–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ma F, Zhang J, Zhong L, Wang L, Liu Y, Wang Y, Peng L, Guo B. Upregulated microRNA-301a in breast cancer promotes tumor metastasis by targeting PTEN and activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Gene 2014;535(2):191–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chang YW, Chen MW, Chiu CF, Hong CC, Cheng CC, Hsiao M, Chen CA, Wei LH, Su JL. Arsenic trioxide inhibits CXCR4-mediated metastasis by interfering miR-520h/PP2A/NF-κB signaling in cervical cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(4):687–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lu Z, Li Y, Takwi A, Li B, Zhang J, Conklin DJ, Young KH, Martin R, Li Y. miR-301a as an NF-κB activator in pancreatic cancer cells. EMBO J. 2011;30(1):57–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]