Abstract

Background

Vedolizumab is approved for moderate to severe Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). We present prospective, 1-year data of the real-world effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab in inflammatory bowel disease.

Methods

Consecutive patients receiving vedolizumab for treatment of UC or CD with at least 14 weeks of follow-up, regardless of outcome, were included. Patients had clinical activity scores (Harvey-Bradshaw Index [HBI] or Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index [SCCAI]) and inflammatory markers prospectively measured at baseline and weeks 14, 30, and 52. Clinical response was defined as a reduction ≥3 in HBI or SCCAI, clinical remission as HBI ≤4 or SCCAI ≤2, steroid-free remission as clinical remission without the need for corticosteroids, and mucosal healing (assessed at 6 months) as a Mayo endoscopic subscore of 0 or 1 or CD-SES <3.

Results

A total of 132 patients were included: 61 (45%) male, 94 (71%) with CD, 42 (29%) with UC; 22% and 34% of CD and UC patients, respectively, achieved steroid-free remission by week 14. This increased to 31% in CD patients and plateaued at 35% in UC patients at 12 months. Increasing remission rates to 6 months were seen in patients with CD, but minimal improvements after 3 months of therapy occurred in those with UC. Mucosal healing was achieved in 52% of UC and 30% of CD patients. Most adverse events were minor; 74% remained on vedolizumab at 12 months.

Conclusions

In this real-world study, vedolizumab demonstrated similar efficacy and safety seen in pivotal trials, with sustained clinical response in the majority of patients. Similar rates of response were seen in UC and CD patients.

Keywords: vedolizumab, inflammatory bowel disease, alpha-4 integrin inhibitors, response to therapy, biological therapy

INTRODUCTION

Current treatment goals for patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) or ulcerative colitis (UC) include the induction and maintenance of clinical remission of the disease and achievement of mucosal healing.1 Anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–α therapies are highly efficacious in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and their availability has dramatically changed the treatment algorithm of IBD. However, despite their effectiveness, alternative therapies to anti-TNFα agents are essential, as a number of patients do not respond to these therapies and their use has been associated with loss of response and adverse effects such as infections and malignancy.2, 3

For intestinal inflammatory disease in patients with IBD, anti-integrin therapies target the adhesion and migration of leukocytes across the endothelium of inflamed tissues, and they are effective and safe in placebo-controlled trials.4–6 Vedolizumab is a selective humanized immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody to α4β7 integrin that modulates gut lymphocyte trafficking7 and has been approved by regulatory agencies in the United States, Europe, and Australia for use in moderate to severe CD and UC. To date, experience with real-world drug utilization and exposure has been limited to either short-term clinical follow-up, retrospective data, or data failing to report on endoscopic outcomes,8–13 and there have been no real-world reports of histological outcomes.

Here, we report our real-world vedolizumab experience in a high-volume tertiary care setting with patients who were followed prospectively for up to 52 weeks. Our aim was to characterize the clinical remission and response rates and durability of response while utilizing clinical, endoscopic, and histological outcome measures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design and Setting

This was a prospective, single-center observational cohort study of adult patients (age 18 years or older) who commenced vedolizumab for the treatment of IBD at the University of Chicago Medicine IBD Center. Consent was obtained from consecutive patients initiating vedolizumab between its Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval (May 20, 2014) and August 30, 2015, for the treatment of CD or UC. Patients were eligible to be included if they had a confirmed clinical, endoscopic, or histological diagnosis of CD or UC. Baseline characteristics were extracted from our IBD clinical registry and via chart review. Outcomes were collected prospectively at follow-up at weeks 14, 30, and 52. Patients who had at least 14 weeks of follow-up at University of Chicago Medicine from their first vedolizumab infusion, whether still maintained on vedolizumab or not, were included in the final analysis. Endoscopic reports at our center routinely include documentation of extent and severity of findings as described in the Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s disease (SES-CD) and the Mayo Endoscopic Subscore (Mayo score).

Intervention

All patients received vedolizumab according to the FDA-approved dosing regimen for IBD. Under this protocol, 300 mg of vedolizumab is administered via intravenous infusion over 30 minutes. Induction dosing occurred at weeks 0, 2, and 6, with standard maintenance dosing at 8-week intervals thereafter. Concomitant therapy, prior treatment exposure, and changes to the vedolizumab maintenance regimen (dose escalation) were recorded throughout the study duration. Dose escalation of vedolizumab was at the discretion of the treating physician and was commenced in patients with clinically active UC or CD, in those who were steroid dependent despite 8-weekly vedolizumab, and in those with moderate to severe endoscopic disease activity.

Outcomes

Baseline patient and disease characteristics were recorded, and outcomes were evaluated at weeks 14, 30, and 52 of treatment. Clinical disease activity was assessed with the Harvey-Bradshaw Index (HBI) for CD14 and the Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index (SCCAI) for UC.15 Clinical disease activity was defined as an HBI score greater than 4 for CD and a SCCAI score greater than 2 for UC.

The primary outcome measure was steroid-free remission at week 52, which was defined as clinical remission (HBI score of 4 or less for CD and SCCAI score of 2 or less for UC) without oral glucorticoids (prednisolone or budesonide). Secondary outcomes were clinical response and clinical remission at weeks 14, 30, and 52, steroid-free remission at weeks 14 and 30, and rates of surgery and hospitalization during follow-up. Clinical response was defined as a reduction of at least 3 points in either HBI or SCCAI or achievement of clinical remission in those with clinical disease activity at baseline.

It is routine in our center to perform endoscopic assessment of mucosal healing at 6 months after commencement of biological treatment independent of clinical disease activity. Endoscopic response was assessed utilizing the SES-CD for CD16 or Mayo endoscopic subscore for UC patients17 in patients who had colonoscopic evaluations at baseline and at 6 months after initiation of vedolizumab. In CD, endoscopic improvement was defined as a reduction in the SES-CD of >50%, and mucosal healing (MH) as an SES-CD score <3. In UC, endoscopic improvement was defined as absolute reduction of ≥1 point in the Mayo endoscopic subscore, and MH as a Mayo endoscopic subscore of 0 or 1. Biopsies in CD and UC were interpreted by an expert gastrointestinal pathologist, and histological inflammation was scored on a 4-point scale as quiescent/normal (0), mild (1), moderate (2), or severe (3).18 The highest histological score obtained during the examination was used as the representative score, and biopsies were targeted from areas of most active mucosal disease. Histological improvement was defined as an absolute reduction of at least 1 point, and histological remission as a score of 0. Additional available clinical outcomes were collected from standard of care visits, including laboratory values (C-reative protein [CRP] and fecal calprotectin).

At each visit, patients were questioned about adverse events including infections, infusion reactions, or other potential adverse events related to vedolizumab. Adverse events were graded as serious if they resulted in antibiotic treatment, discontinuation of vedolizumab, or hospitalization.

Statistical Methods

Patients were analyzed on an intent-to-treat basis, and cessation of vedolizumab for any reason, including adverse events or loss of response, was considered a treatment failure with failure to achieve clinical remission from that time forward. Descriptive statistics were provided to summarize demographic characteristics. Pre-treatment and post-treatment clinical activity scores and CRP were compared using the paired t test, pre-treatment and post-treatment endoscopic activity scores were compared using Wilcoxon signed-rank test, and within-group differences for clinical remission, response, steroid-free remission, and histological outcomes at different time points were determined using McNemar’s test. For patients who withdrew therapy prematurely, the last observation from the time of treatment failure was carried forward. Agreement between mucosal and histological outcomes was determined using the kappa statistic. Continuation of vedolizumab was compared between CD and UC patients, anti-TNFα-naive and non-anti-TNFα-naive patients, and patients on an immunomodulator and those on vedolizumab monotherapy using log-rank test and Kaplan-Meier analysis. Variables associated with week 52 glucocorticoid-free remission were explored using logistic regression. Multivariate analysis was performed on variables with a P value <0.2 on univariate analysis using backward step-wise logistic regression. A 2-sided P value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant. All data analyses were performed using Stata 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at University of Chicago Hospital (Institutional Review Board: 14–1371). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

RESULTS

Patients

A total of 184 patients were prescribed and received at least 1 vedolizumab infusion between May 2014 and August 2015; 136 patients had reached 14 weeks of follow-up at University of Chicago Medicine, consented to have their data collected, and were included in this analysis. All 136 were followed for at least 14 weeks from their first infusion, 130 had available week 30 clinical outcomes, and 113 patients had week 52 outcomes assessed (Figure 1). The patient baseline characteristics and indications for vedolizumab are shown in Table 1; 66% (n = 90) of patients had clinically active disease (HBI > 4 or SCCAI > 2) at vedolizumab commencement. Other indications for vedolizumab included corticosteroid dependence in 13% (n = 18), moderate/severe endoscopic disease activity in 11% (n = 15), and concerns regarding the safety of prior maintenance therapy in 6% (n = 8; natalizumab, n = 7; tacrolimus, n = 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of patients included in the vedolizumab study.

Table 1:

Baseline Characteristics

| Characteristic | IBD = 136 | CD = 94 Patients | UC = 42 Patients |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 39 (28–50) | 41 (26–51) | 37 (29–45) |

| Male sex, No. (%) | 61 (45) | 39 (41) | 20 (52) |

| Body weight, median (IQR), kg | 70 (58–84) | 68.2 (56–83) | 72 (61–88) |

| BMI, median (IQR), kg/m2 | 24 (21–28) | 24 (21–2) | 24 (22–27) |

| Current smoker, No. (%) | 8 (6) | 8 (9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Age at diagnosis, median (IQR), y | 22 (15–30) | 21 (15–30) | 27 (20–35) |

| Duration of disease, median (IQR), y | 12 (7–21) | 14 (8–24) | 9 (5–16) |

| Family history of IBD, No. (%) | 42 (31) | 31 (33) | 11 (27) |

| Past surgery for CD, No. (%) | — | 49 (52) | — |

| Previous C. difficile infection, No. (%) | 20 (15) | 14 (15) | 6 (14) |

| Disease location, Montreal Classification, No. (%) | |||

| — | L1: 12 (13) | E1: 1 (2) | |

| L2: 28 (30) | E2: 11 (26) | ||

| L3: 54 (57) | E3: 30 (71) | ||

| L4: 11 (12) P: 34 (36) |

— | ||

| Clinical disease activity at baseline, No. (%) | — | HBI: <5 (remission): 39 (41) 5–7 (mild): 31 (33) 8–16 (moderate): 20 (21) >16 (severe): 4 (4) |

SCCAI: <3 (remission): 7 (17) 3–6 (mild): 22 (52) 7–10 (moderate): 9 (21) >10 (severe): 4 (9) |

| Hb, median (IQR) | 13 (12.0–14.3) | 12.7 (11.7–14.3) | 13.7 (12.5–14.3) |

| WBC, median (IQR) | 7.3 (5.9–9.5) | 7.3 (5.8–9.7) | 7(5.9–8.5) |

| Albumin, median (IQR) | 4.2 (3.9–4.5) | 4.3 (3.9–4.5) | 4.1 (3.9–4.4) |

| Fecal calprotectin (n = 39), median (IQR) | 431 (135–951) | 414 (113–876) | 474 (237–951) |

| C-reactive protein (n = 97), mean (SD) | 13 (25) | 12 (17) | 14 (36) |

| Concomitant medications, No. (%) | |||

| Oral prednisolone | 57 (42) | 35 (37) | 22 (52) |

| Oral corticosteroida | 76 (56) | 48 (51) | 28 (67) |

| Thiopurines | 35 (26) | 27 (29) | 8 (19) |

| Methotrexate | 16 (12) | 12 (13) | 4 (10) |

| Calcineurin inhibitor | 17 (12) | 8 (9) | 9 (21) |

| Prior anti-TNF therapy, No. (%) | |||

| Naive | 17 (13) | 4 (4) | 13 (31) |

| 1 failure | 40 (29) | 22 (23) | 18 (43) |

| >1 failure | 79 (58) | 68 (72) | 11 (26) |

| Reason for failing anti-TNF therapy, No. (%) | |||

| Primary nonresponse | 35 (29) | 23 (26) | 12 (41) |

| Secondary LOR | 52 (44) | 40 (44) | 12 (41) |

| Unacceptable side effects | 32 (27) | 27 (30) | 5 (17) |

| Indication for vedolizumab, No. (%) | |||

| Clinical disease activity | 90 (66) | 55 (59) | 35 (83) |

| Clinical remission | 46 (34) | 39 (41) | 7 (17) |

| Endoscopic disease activity | 15 (11) | 14 (15) | 1 (2) |

| Safety concerns natalizumab/tacrolimus | 8 (6) | 7 (7) | 1 (2) |

| Refractory perianal disease | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| SE from previous medication | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (5) |

| Corticosteroid dependence | 18 (13) | 15 (6) | 3 (7) |

| Budesonide dependence | 9 (7) | 7 (7) | 2 (5) |

| Systemic corticosteroid dependence | 9 (7) | 8 (9) | 1 (2) |

| Maintenance postreversal of diversion | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

BMI = body mass index; LOR = loss of response; SE = side effect; WBC = white blood cells.

aIncludes budesonide.

Clinical Response and Remission

Crohn’s disease

In CD patients with clinical disease activity at baseline (n = 55, 59%), 58% (n = 32) achieved clinical response by week 14, 73% (n = 38) by week 30, and 56% (n = 25) had a clinical response by week 52. Clinical remission was achieved in 38% (n = 21) by week 14, 62% (n = 32) by week 30, and 51% (n = 23) by week 52. Steroid-free clinical remission was achieved in 22% (n = 12) by week 14, 44% (n = 23) by week 30, and 31% (n = 14) by week 52. The increase in clinical remission and steroid-free remission rates was significant between weeks 14 and 30 (P = 0.02), but this cumulative benefit was lost by week 52 (Figure 2A).

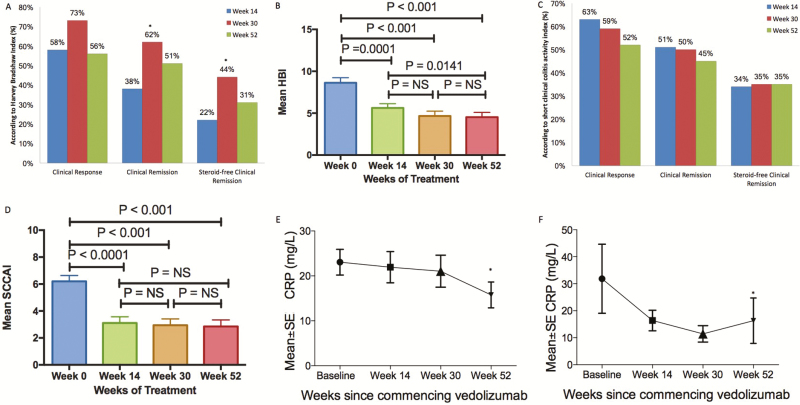

FIGURE 2.

Change in clinical and biochemical markers of disease activity after vedolizumab treatment. A, Crohn’s disease clinical response and remission rates. *Signifies P < 0.05 when comparing efficacy with week 14, determined using McNemar’s test. B, Mean (SE) Harvey-Bradshaw Index. Clinical disease activity continued to improve to 52 weeks. C, Ulcerative colitis clinical response and remission rates. D, Mean SCCAI (SE). Clinical activity improved up to week 14 but then appeared to stabilize. E, Mean C-reactive protein (SE) at weeks 0, 14, 30, and 52 in CD patients with elevated CRP at baseline. F, Mean C-reactive protein (SE) at weeks 0, 14, 30, and 52 in UC patients with elevated CRP at baseline.

Mean HBI significantly improved from a mean baseline score of 8.6 (SD, 4.4) to 5.6 (SD, 3.7) at week 14, 4.7 (SD, 4.2) at week 30, and 4.5 (SD, 4.2) at week 52. There was significant improvement between week 14 and week 52 but not between week 14 and week 30 or week 30 and week 52 (Figure 2B).

Of the 39 CD patients in clinical remission at baseline, 97% (n = 38) maintained remission at week 14, 89% (n = 34) by week 30, and 77% (n = 24) maintained remission at week 52; 53% of patients who were in clinical remission but steroid-dependent achieved corticosteroid-free remission on follow-up.

Overall, 48 patients were receiving glucocorticoids at vedolizumab initiation; 27% (n = 13) were steroid-free and 15% (n = 7) were in steroid-free remission at week 14, 57% (n = 25) were steroid-free and 39% (n = 18) were in steroid-free remission at week 30, and 48% (n = 19) were steroid-free and 33% (n = 13) were in steroid-free remission at week 52.

Ulcerative colitis

In UC patients with clinical disease activity at baseline (n = 35, 77%); 63% (n = 22) of patients achieved clinical response by week 14, 59% (n = 20) at week 30, and 52% (n = 16) at week 52. Clinical remission was achieved in 51% (n = 18) by week 14, 50% (n = 17) at week 30, and 45% (n = 14) were in clinical remission at 1 year. Steroid-free remission was achieved in achieved in 34% (n = 12) at week 14, 35% (n = 12) at week 30, and 35% (n = 11) by 1 year. There was no change in rates of remission or response between week 14 and weeks 30 or 52.

Mean SCCAI significantly improved from a baseline of 6.20 (SD, 2.58) to 3.11 (SD, 2.69) at week 14, 2.94 (SD, 2.79) at week 30, and 2.86 (SD, 2.85) at week 52. There was no significant improvement between week 14 and week 30 or week 14 and week 52 (Figure 2D).

Of the 7 UC patients in remission at baseline, 71% (n = 5) remained in remission at week 14, 50% (n = 3) at week 30, and 83% (n = 5) were in remission at 1 year. Of the 3 patients who were steroid-dependent at baseline, 1 achieved steroid-free remission.

Overall, 28 UC patients were receiving oral glucocorticoids at vedolizumab initiation; 38% (n = 10) were steroid-free and 21% (n = 6) were in steroid-free remission by week 14, 72% (n = 13) were steroid-free and 22% (n = 6) were in steroid-free remission at week 30, and 35% (n = 9) were steroid-free and 24% (n = 6) were in steroid-free remission at week 52.

C-reactive reactive protein

Of 74 CD patients with serial C-reactive protein measurements, mean CRP decreased from week 0 to week 52 (P = 0.021), but not between week 0 and week 14 or week 0 and week 30. Of 37 patients who had elevated CRP at baseline (CRP > 5), 24% (n = 9) normalized their CRP by week 14, 30% (n = 11) by week 30, and 41% (n = 15/37) by 1 year. In these patients, CRP significantly decreased between week 0 and week 52 (Figure 2E).

Of 38 UC patients with serial CRP measurements, mean CRP did not significantly decrease with treatment; 31% (n = 5/16) of patients with elevated CRP at baseline normalized their CRP at week 14, 38% (n = 6/16) by week 30, and 44% (n = 7/16) at week 52. Change in CRP in these patients significantly decreased between week 0 and week 52 (Figure 2F).

Mucosal Healing

Sixty-six patients (22 UC, 44 CD) had baseline and postinduction endoscopic assessment at a median time of 6 months (interquartile range [IQR], 5–8). There was no difference between frequency of endoscopic assessment in those who continued vs those who ceased vedolizumab therapy (51% who continued vedolizumab to week 52 had endoscopic assessment vs 46% of those who ceased vedolizumab having endoscopic assessment, P = NS) or in those who achieved week 52 steroid-free remission vs those who did not (50% who achieved week 52 steroid-free remission underwent endoscopic assessment vs 56% of those who did not achieve week 52 steroid-free remission under-went endoscopic assessmemt). Endoscopic and histological scores before and after vedolizumab therapy are shown in Figure 3, A–D.

FIGURE 3.

Endoscopic and histological scores before and after vedolizumab. Pre-treatment and post-treatment SES-CD scores and Mayo endoscopic subscores were compared using Wilcoxon signed-rank test and within group differences for histological outcomes were compared using McNemar's test. Significance level P < 0.05. A, SES-CD scores in CD patients before and after vedolizumab. B, Histological scores in CD patients before and after vedolizumab. C, Mayo endoscopic subscores in UC patients before and after vedolizumab. D, Histological scores in UC patients before and after vedolizumab.

Of 44 patients with CD, 43 had active mucosal inflammation at baseline, of which 40% achieved endoscopic improvement and 30% MH. There was significant improvement in endoscopic activity, with the median SES-CD improving from 12 (IQR, 6–15) to 7 (IQR, 1–12; P < 0.001). Thirty-seven patients with CD had active histological inflammation at baseline and follow-up histology; 57% achieved histological improvement and 22% histological remission. The improvement in histological scores was significant (P = 0.016). There was a strong correlation between mucosal and histological healing, with a 92% agreement between the 2 outcomes (Κ, 0.79; P ≤ 0.001). In the setting of mucosal healing, 72% of patients also achieved histological healing, compared with no patients achieving histological healing when endoscopic activity was present. Patients who achieved MH (81% vs 17%, P < 0.001), mucosal improvement (60% vs 20%, P = 0.010), histological improvement (57% vs 8%, P = 0.004), and histological healing (86% vs 26%, P = 0.004) had significantly higher rates of steroid-free remission at 1 year.

Of 22 patients with UC, 21 had a Mayo endoscopic score >0, and 18 patients had active endoscopic activity. Of these, 57% had endoscopic improvement and 52% achieved MH. There was significant improvement of endoscopic activity, with the median Mayo score decreasing from 2 (IQR, 2–3) to 1 (P = 0.011).1–3 Seventeen patients had active histological inflammation at baseline and follow-up histology; 69% achieved histological improvement and 53% histological remission. The improvement in histological score with treatment was significant (P = 0.013). There was moderate correlation between mucosal and histological healing, with 79% agreement between the 2 outcomes (Κ, 0.57; P = 0.005). In the setting of mucosal healing, 75% of patients also achieved histological healing and 5% (n = 1) of patients appeared to have endoscopic activity despite histological healing. Week 52 steroid-free remission was greater in patients who achieved mucosal healing (70% week 52 steroid-free remission in those who achieved mucosal healing vs 20% in those who did not achieve mucosal healing, P = 0.025), and histological healing (78% week 52 steroid-free remission in those who achieved histological healing vs 13% in those who did not achieve histological healing, P = 0.0070) was achieved.

Ninety-six percent (n = 24/25) of patients with IBD who achieved MH at postinduction colonoscopy continued treatment with vedolizumab, and no patient required surgery at follow-up. Of the 42 patients who did not achieve MH, 36% ceased vedolizumab therapy and 19% proceeded to colectomy. Patients were more likely to continue on vedolizumab therapy at week 52 when MH was achieved on colonoscopy (96% vs 64%, P = 0.003) (Figure 4A).

FIGURE 4.

Proportion of patients remaining on vedolizumab during follow-up. A, Patients who achieve MH vs those with mucosal inflammation. B, Crohn’s disease vs ulcerative colitis. C, Anti-TNFα-naive vs not anti-TNFα-naive. D, On concurrent treatment with immunomodulator vs not on concurrent immunomodulator.

Vedolizumab Dose Escalation

Forty-three patients (32%: 30 CD, 13 UC) underwent dose escalation of vedolizumab to Q4 (n = 40) or Q6 (n = 3) weeks; 36 (84%) were dose-escalated for active clinical disease, 5 (12%) for glucocorticoid dependence, and 2 (5%) for nonhealing perianal disease. At median follow-up of 6 months (IQR, 4–7 months) after dose escalation, 24 (56%) patients achieved clinical remission, of which 12 (26%: 8 CD, 4 UC) achieved glucocorticoid-free clinical remission. Eighteen (42%) patients had no clinical response, of which 10 (23%: 6 CD, 4UC) ceased vedolizumab. Of the 5 patients who were steroid-dependent before dose intensification, 2 (40%) achieved steroid-free remission. Neither patient with refractory perianal disease responded to the higher dose of vedolizumab.

Predictors of Response to Vedolizumab

Univariate and multivariate predictors of week 52 steroid-free remission are shown in Table 2.

Table 2:

Univariate and Multivariate Predictors for Week 52 Steroid-Free Remission Following Treatment With Vedolizumab

| Variables Predicting Week 52 Steroid-Free Remission | Crohn’s Disease (N = 75) | Ulcerative Colitis (N = 37) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Analysis OR (95% CI) |

P a | Multivariate Analysis AOR (95% CI) |

P a | Univariate Analysis OR (95% CI) |

P a | Multivariate Analysis AOR (95% CI) |

P a | |

| Age of diagnosis, y | 0.98 (0.94–1.01) | 0.226 | 1.04 (0.98–1.11) | 0.179b | ||||

| Age commenced Rx, y | 1.00 (0.97–1.03) | 0.747 | 1.02 (0.96–1.08) | 0.504 | ||||

| Sex | 1.31 (0.51–3.35) | 0.569 | 2.67 (0.66–10.70) | 0.167b | ||||

| Disease distribution | Colonic vs ileal: 0.87 (0.18–4.14) Ileocolonic vs ileal: 1.04 (0.25–4.40) |

0.856 0.956 |

Extensive vs left-sided/ proctitis: 0.75 (0.16–3.44) |

0.711 | ||||

| Penetrating disease | 0.86 (0.29–2.58) | 0.790 | NA | |||||

| Oral steroids at baseline | 0.375 (0.14–0.99) | 0.049a | 0.12 (0.03–0.59) | 0.009a | ||||

| On immunomodulatorc | 0.98 (0.39–2.47) | 0.970 | 1.33 (0.30–5.96) | 0.706 | ||||

| Anti-TNF-naive | NA | NA | 1.52 (0.37–6.29) | 0.565 | ||||

| Current smoker | 0.48 (0.09–2.63) | 0.396 | 0.91 (0.14–5.78) | 0.920 | ||||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 1.05 (0.97–1.14) | 0.254 | 1.01 (0.89–1.14) | 0.928 | ||||

| Clinical score (increase in HBI in CD and SCCAI in UC) | 0.84 (0.74–0.95) | 0.006a | 0.87 (.76–.99) | 0.038a | 0.82 (0.66–1.06) | 0.139b | ||

| Week 14 clinical remission | 3.13 (1.15–8.49) | 0.026a | 13.36 (2.33–76.47) | 0.004a | ||||

| Week 14 steroid-free clinical remission | 4.34 (1.61–11.69) | 0.004a | 23.33 (3.98–136.80) | < 0.001a | 23.33 (3.98–136.90) | < 0.001a | ||

| Week 30 clinical remission | 5.44 (1.62–18.25) | 0.006a | 13.36 (2.33–76.47) | 0.004a | ||||

| Week 30 steroid-free clinical remission | 11.25 (3.71–34.11) | <0.001a | 9.55 (3.04–29.99) | <0.001a | 38.00 (4.53–318.78) | 0.001a | ||

BMI = body mass index.

aSignificance level (significant P < 0.05).

bIncorporated into multivariate analysis as P < 0.2.

cPatients taking either methotrexate, azathioprine, or 6-mercaptopurine when commencing vedolizumab.

In patients with CD, predictors of week 52 steroid-free remission on univariate analysis were corticosteroid use at baseline (odds ratio [OR], 0.375; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.14–0.99; P = 0.049), lower baseline clinical disease activity score (HBI; OR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.74–0.95; P = 0.006), and achieving week 14 clinical remission (OR, 3.13; 95% CI, 1.15–8.49; P = 0.026), week 14 steroid-free remission (OR, 4.34; 95% CI, 1.61–11.69; P = 0.004), week 30 clinical remission (OR, 5.44; 95% CI, 1.62–18.25; P = 0.006), and week 30 steroid-free remission (OR, 11.25; 95% CI, 3.71–34.11; P < 0.001).

Use of concomitant immunomodulators (P = 0.97) was not associated with week 52 steroid-free remission. Only 1 patient was anti-TNFα-naive, so this could not be assessed for prediction of response to therapy.

Because collinearity between week 14 and week 30 clinical outcomes was demonstrated, week 14 clinical outcomes and week 30 clinical remission were removed from the multivariate analysis. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that patients with increased clinical disease severity at baseline based on the HBI (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 0.87; 95% CI, 0.76–0.99; P = 0.038) were less likely to achieve week 52 steroid-free remission, and achieving week 30 steroid-free remission (AOR, 9.55; 95% CI, 3.04–29.99; P < 0.001) predicted week 52 steroid-free remission.

In patients with UC, predictors of week 52 steroid-free remission included concomitant steroid use when commencing vedolizumab (OR, 0.12; 95% CI, 0.03–0.59; P = 0.009), achieving week 14 remission (OR, 13.36, 95% CI, 2.33–76.47; P = 0.004), week 14 steroid-free remission (OR, 23.33; 95% CI, 3.98–136.80; P < 0.001), week 30 clinical remission (OR, 13.36; 95% CI, 2.33–76.47; P = 0.004), and week 30 steroid-free remission (OR, 38.00; 95% CI, 4.53–318.78; P = 0.001). Being anti-TNFα-naive (P = 0.565) and use of concomitant immunomodulators (P = 0.706) were not associated with week 52 steroid-free remission.

Because collinearity between week 14 and week 30 clinical outcomes was demonstrated, week 14 clinical remission and week 30 clinical outcomes were removed from the multivariate analysis, which demonstrated that only week 14 steroid-free remission independently predicted week 52 steroid-free remission (AOR, 23.33; 95% CI, 3.98–136.80; P < 0.001).

Vedolizumab Discontinuation and Adverse Events

Thirty-five (26%) patients discontinued vedolizumab: 31 patients due to nonresponse and 4 due to side effects. There was no difference between vedolizumab discontinuation rates in patients with CD compared with UC, or among those previously exposed to anti-TNFα therapy or on an immunomodulator (Figure 4, B–D). Nineteen patients (14%: 11 CD, 8 UC) required an IBD-related surgery during the 52 weeks of follow-up. Surgical procedures included colectomies (n = 15, 8 UC), stricturoplasty (n = 1), ileal resection (n = 1), and diverting stoma (n = 22). Four of these patients continued vedolizumab.

Adverse events are summarized in Table 3. Over the 113 patient-years of follow-up, there was a total of 11 (9.7 per 100 person-years of follow-up [PYF]) serious noninfectious events and 17 (12.8 per 100 PYF) serious infectious events. Two patients discontinued treatment because of an infusion-related reaction: 1 described pruritus, swelling of the tongue and throat and rash, and 1 patient described severe flu-like symptoms and fever. Two patients ceased therapy secondary to an allergic-type rash. Seven patients developed new-onset arthropathy, and 1 required discontinuation of treatment. Two patients were diagnosed with basal cell carcinoma, and 4 patients required hospitalization for severe anemia or gastrointestinal bleeding, 2 of which required a blood transfusion. The majority of serious infections were enteric or sinopulmonary; 6 tested positive for Clostridium difficile by polymerase chain reaction assay of stool, and all these patients responded to treatment with oral vancomycin and remained on vedolizumab. One patient who was also receiving prednisolone, budesonide, and methotrexate developed Candida glabrata and Staphylococcal epidermitidis sepsis. This patient proceeded to colectomy but recommenced vedolizumab postoperatively.

Table 3:

Adverse Events on Vedolizumab

| Event | Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease (n = 136) | Rate of Occurrence: per 100 Person-years of Follow-up |

|---|---|---|

| Adverse event: noninfectious | ||

| Headache | 3 total | 2.7 per 100 PYF |

| Neurological complaints (n = 3) | 3 total -1 paresthesia -1 eye floaters -1 photophobia |

2.7 per 100 PYF |

| Paradoxical skin manifestation | 6 total | 5.3 per 100 PYF |

| Pruritis | 4 total | 3.5 per 100 PYF |

| GI bleed or drop in hemoglobin | 4 total | 3.5 per 100 PYF |

| Athralgia | 14 total -7 new-onset arthralgia (1 ceased therapy) -7 worsening of previous arthralgia |

12.4 per 100 PYF |

| Infusion related reaction | 2 total | 1.8 per 100 PYF |

| Cancer | 2 BCCs No other cancer documented |

1.8 per 100 PYF |

| Constipation | 5 total | 24.6 per 100 PYF |

| Perianal disease | 10 total -3 new perianal fistula -1 new entero-vaginal fistula -5 worsening perianal fistula -1 worsening hidradenitis |

4.4 per 100 PYF |

| Fatigue | 1 | 0.9 per 100 PYF |

| Nausea | 3 | 2.7 per 100 PYF |

| Any serious noninfectious eventa | 11 total | 9.7 per 100 PYF |

| Adverse event: infections | ||

| Enteric infection | 8 total -6 Clostridium difficile: all responded to oral vancomycin -1 viral enteritis -1 CMV colitis All continued therapy after treatment |

7.1 per 100 PYF |

| Flu or flu-like infection | 5 total | 4.4 per 100 PYF |

| URTI | 3 total | 2.6 per 100 PYF |

| Sinopulmonary infections | 7 total -2 pneumonia -1 pharyngitis -4 sinusitis |

6.2 per 100 PYF |

| Postoperative complications | 2 total -1 postoperative stomal infection with muco-cutaneous separation -1 necrotic abdominal wound after creation of diverting stoma |

1.8 per 100 PYF |

| Miscellaneous | 4 total -1 hand-foot-mouth dx -1 G-tube site infection -1 herpes zoster -1 UTI |

3.5 per 100 PYF |

| Sepsis | 1 total | 0.9 per 100 PYF |

| Any serious infectiona | 17 total | 12.8 per 100 PYF |

BCC = basel cell carcinoma; CMV = cytomegalovirus; GI = gastrointestinal; URTI = upper respiratory tract infection; UTI = urinary tract infection.

aA serious adverse event or infection was defined as any adverse event when leading to treatment interruption, antibiotic therapy, hospitalization, disability or persistent damage, colectomy, or death.

DISCUSSION

This study confirms the long-term efficacy of vedolizumab in patients with CD and UC at a tertiary medical center. Currently, there are limited data on vedolizumab outcomes in clinical practice at 1 year.12, 13 Our study differed from previous reports in that data were collected prospectively and that outcomes in patients with UC and both endoscopic and histological data were included.

We have demonstrated that vedolizumab is effective in UC and CD for inducing clinical response and remission, and for maintaining remission over 1 year. In both UC and CD, vedolizumab achieved steroid-free remission in one-third of patients with active disease at 1 year. This outcome was seen in patients with complex disease phenotypes, and in those who had previously failed biologic therapies. Unique findings for both CD and UC included the achievement of clinical remission in half of the patients at 1 year, maintenance of remission over long-term follow-up of those in clinical remission when commencing treatment, and induction of histological improvement and remission. Mucosal and histological healing was associated with steroid-free remission, and continued vedolizumab therapy and dose escalation were appropriate for some patients.

Our prospective study demonstrates similar efficacy and safety as seen in the pivotal trials,5, 6 but our rates of remission after induction treatment are higher and similar to those reported in previously published cohort studies of week 14 outcomes.8–12 This is likely due to the fact that we evaluated postinduction response and remission after 14 rather than 6 weeks, allowing more time for the mechanism of this therapy to effect a clinically measurable change. We found that 58% of CD patients achieved clinical response, 38% achieved clinical remission, and 22% achieved steroid-free remission by week 14. This is similar to previous cohort studies, with the largest cohort, by Amiot et al.,10 demonstrating response rates of 64%, remission rates of 36%, and steroid-free remission rates of 31% at week 14. In our study, clinical remission and steroid-free remission significantly increased to a maximum level of 62% and 44%, respectively, by week 30 and then plateaued out to 51% and 31% at week 52. Our rates of steroid-free remission were similar to that reported by Dulai et al.12 of 34% after 12 months of therapy and confirm their findings and those observed in the GEMINI trial, that the effectiveness of vedolizumab appears to be time-dependent in CD, with greatest benefit appearing after 6 months of therapy.6, 19

In the current study, UC patients had similar rates of efficacy to CD patients, with 63% achieving clinical response, 51% achieving clinical remission, and 34% steroid-free remission by week 14. Again, this is similar to that reported in previous cohort studies, with Amiot et al.10 demonstrating response rates of 57%, remission rates of 39%, and steroid-free remission rates of 36% at week 14. Unlike in CD, remission rates in UC patients did not vary significantly after 14 weeks of therapy, with clinical remission and steroid-free remission rates of 50% and 35% at week 30 and 45% and 35% at week 52, respectively. Our study is the first to provide long-term follow-up on UC patients and demonstrates that, unlike CD, there is no increasing benefit beyond 14 weeks of follow-up. This is similar to what was demonstrated in the Gemini clinical trials and has important clinical implications regarding when clinicians should consider alternative mechanisms of management in the nonresponding patient.

Of patients with active endoscopic disease at baseline, 30% of CD and 52% of UC patients achieved MH with vedolizumab therapy. For UC, this is comparable to the results of the pivotal trial, which demonstrated rates of 41% for MH in induction and 54% in maintenance.5 The pivotal trials for CD did not report MH, but a prospective study reported 30%, and a retrospective study found that 50% of patients with CD achieve MH.8 The latter study had significant limitations due to the nonstandardized reporting of MH.

In addition to confirming vedolizumab as an effective agent to achieve endoscopic MH in CD patients, this study has uniquely demonstrated in both UC and CD, first, that MH is associated with continued vedolizumab treatment; second, that vedolizumab is effective at achieving histological improvement and remission; and third, that the majority of patients who achieve mucosal healing will also achieve histological healing. This is a clinically significant outcome of interest and of particular importance given the cellular-based mechanism of action of this therapy.

Unique in this study is that we report the benefit of dose escalation of vedolizumab, achieved by decreasing the interval between infusions, in both UC and CD. After a minimum of 3 months of dose escalation, 26% of 43 patients who were dose-escalated for clinical disease activity subsequently achieved glucocorticoid-free clinical remission. This is higher than the 13% reported previously, although reports of clinical response in this retrospective study were high (40%).12 This finding supports the notion that, similar to our other monoclonal antibodies, increased dosing intervals for this therapy are beneficial in some patients.

Similar to the considerable safety information from the pivotal GEMINI studies and cohort studies,20 we found vedolizumab to be very safe and associated with a low side effect profile, with the majority of adverse events being related to enteric or sinopulmonary infections or new-onset joint pain. Rarely did this result in the requirement of vedolizumab discontinuation.

The major limitations of our study were the sample size, particularly in regards to predictors of response to vedolizumab, and that, despite the prospective nature of the study, some data were missing from patients due to incomplete follow-up. In addition, given the tertiary setting and the expectation of this therapy arriving in the US market, this patient group likely has more medically resistant disease than in the general community, which may have underestimated the response rates of vedolizumab in less severe patients. Furthermore, as not all patients underwent endoscopic assessment, there is a possibility that the rates of mucosal healing are overestimated secondary to selection bias, with patients deemed primary nonresponders less likely to undergo endoscopic assessment. We believe that this bias is limited as patients may also have been selected to undergo endoscopic assessment when failing vedolizumab and rates of endoscopic assessment were no different in those who achieved week 52 steroid-free remission and in those who did not. In addition, reassuringly, our rates of mucosal healing are similar in UC to the large clinical trials5 but are less than those reported in retrospective clinical studies for CD.8 Finally, the histological scale used here to assess histological activity and quiescence has not undergone independent validation.

In conclusion, in our tertiary IBD practice, we demonstrate that vedolizumab is effective, durable, and safe in patients with complex and treatment-resistant CD and UC. We further confirm the efficacy in patients who are anti-TNFα-naive and those who are anti-TNFα-experienced, and we uniquely extend the data demonstrating durable efficacy to UC patients. We provide evidence for the benefit of dose intensification and introduce the role of endoscopic and histological improvement in this population.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Thanks to Dania Saddiqui who helped with patient recruitment and data collection.

Conflicts of interest

David T. Rubin has received institutional grant support from Abbvie, Janssen, and Takeda and served as a consultant for Abbvie, Janssen, Takeda, Amgen, Pfizer, and UCB. Russell D. Cohen has received institutional grant support from Abbvie, Janssen, and Takeda and served as a consultant for Abbvie, Janssen, Takeda, and UCB. Peter R. Gibson has served as consultant or advisory board member for AbbVie, Ferring, Janssen, Merck, Nestle Health Science, Danone, Allergan, Celgene, and Takeda. His institution has received speaking honoraria from AbbVie, Janssen, Ferring, Takeda, Fresenius Kabi, Mylan, and Pfizer. He has received research grants for investigator-driven studies from AbbVie, Janssen, Falk Pharma, Danone, and A2 Milk Company.

Britt Christensen has received travel grants from Takeda.

Supported by

This work was funded in part by the Digestive Diseases Research Core Center and a National Institute of Health Grant (grant number P30DK42086). Britt Christensen receives support through an “Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.” This is an investigator-initiated study, and has no industry funding.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lichtenstein GR, Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ; Practice Parameters Committee of American College of Gastroenterology Management of Crohn’s disease in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:465–83; quiz 464, 484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roda G, Jharap B, Neeraj N, Colombel JF. Loss of response to anti-tnfs: definition, epidemiology, and management. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2016;7:e135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonovas S, Fiorino G, Allocca M et al. Biologic therapies and risk of infection and malignancy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1385–397.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lobatón T, Vermeire S, Van Assche G et al. Review article: anti-adhesion therapies for inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:579–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE et al. ; GEMINI 1 Study Group Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:699–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P et al. ; GEMINI 2 Study Group Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:711–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soler D, Chapman T, Yang LL et al. The binding specificity and selective antagonism of vedolizumab, an anti-alpha4beta7 integrin therapeutic antibody in development for inflammatory bowel diseases. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;330:864–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vivio EE, Kanuri N, Gilbertsen JJ et al. Vedolizumab effectiveness and safety over the first year of use in an IBD clinical practice. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:402–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shelton E, Allegretti JR, Stevens B et al. Efficacy of vedolizumab as induction therapy in refractory IBD patients: a multicenter cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:2879–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amiot A, Grimaud JC, Peyrin-Biroulet L et al. ; Observatory on Efficacy and of Vedolizumab in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease Study Group; Groupe d’Etude Therapeutique des Affections Inflammatoires du Tube Digestif Effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab induction therapy for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1593–1601.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baumgart DC, Bokemeyer B, Drabik A et al. ; Vedolizumab Germany Consortium Vedolizumab induction therapy for inflammatory bowel disease in clinical practice–a nationwide consecutive German cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:1090–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dulai PS, Singh S, Jiang X et al. The real-world effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab for moderate-severe Crohn’s disease: results from the US VICTORY consortium. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stallmach A, Langbein C, Atreya R et al. Vedolizumab provides clinical benefit over 1 year in patients with active inflammatory bowel disease - a prospective multicenter observational study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:1199–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harvey RF, Bradshaw JM. A simple index of Crohn’s-disease activity. Lancet. 1980;1:514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walmsley RS, Ayres RC, Pounder RE et al. A simple clinical colitis activity index. Gut. 1998;43:29–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daperno M, D’Haens G, Van Assche G et al. Development and validation of a new, simplified endoscopic activity score for Crohn’s disease: the SES-CD. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:505–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1625–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joseph N, Weber C. Pathology of inflammatory bowel disease. In: Baumgart D, ed. Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis. New York: Springer; 2011:287–306. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sands BE, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P et al. Effects of vedolizumab induction therapy for patients with Crohn’s disease in whom tumor necrosis factor antagonist treatment failed. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:618–27.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colombel JF, Sands BE, Rutgeerts P et al. The safety of vedolizumab for ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2017;66:839–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]