Abstract

Furosemide is one of the most common drug used to treat anasarca in childhood nephrotic syndrome. It has minimal side effects on short-term usage, but prolonged use can result in polyuria, hypokalemia and metabolic alkalosis. This pseudo-bartter complication can be treated by discontinuation of the drug with adequate potassium replacement. We report a child who was given furosemide for 20 days elsewhere to treat the edema due to nephrotic syndrome and then presented to us with bartter-like syndrome. Furosemide was discontinued and potassium replacement was initiated. However, the child continued to have polyuria leading to repeated episodes of hypotensive shock. In view of severe symptoms, she was given a short course of oral indomethacin for 6 days, to which she responded. This case highlights the fact that indomethacin can provide symptomatic improvement in furosemide induced pseudo-bartter.

Keywords: Furosemide, Pseudo bartter syndrome, Potassium, Metabolic alkalosis, Indomethacin

Introduction

Furosemide is a common drug used to decrease edema in patients with nephrotic syndrome. The mechanism of action is through blockage of sodium–potassium–chloride symporter in the ascending limb of loop of henle [1]. Electrolyte abnormalities, which includes hyponatremia, hypokalemia and hypercalciuria are common adverse effects of furosemide. However, its prolonged use can result in pseudo-bartter with polyuria, metabolic alkalosis and electrolyte wasting [2].

Although cases of furosemide-induced tubular dysfunction have been reported, polyuria causing repeated episodes of hypotensive shock and use of prostaglandin synthesis inhibitor in treating it is limited in the literature [3, 4]. We, hereby report a case of furosemide-induced tubular dysfunction which responded to a short course of indomethacin, after taking due approval from the Departmental Review Board.

Case

A 3 years 6 months old girl presented with history of loose stools followed by generalised anasarca. She had been admitted in another hospital for 20 days, where she was found to have nephrotic range proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia and hypercholesterolemia. A diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome was made and was started on prednisolone (2 mg/kg/day). For edema, she was initiated on oral furosemide (4 mg/kg/day) and for hypertension, oral enalapril (0.3 mg/kg day) was given. As she was having persistent loose stools, polyuria and hypokalemia, she was referred to our centre.

At admission to our centre, her weight and height were 8.1 kg and 81 cm respectively, both of which were less than − 3 Z scores. Her blood pressure was 94/64 mm Hg (75th to 90th centile) and she had anasarca. Initial investigations revealed hypoalbuminemia (serum albumin 2.2 g/dl), nephrotic range proteinuria (spot urine protein/creatinine ratio—3.1) and hypercholesterolemia (serum cholesterol 415 mg/dl) which confirmed the diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome (Table 1). Further, renal function tests and ultrasound imaging of both kidneys and urinary bladder were normal.

Table 1.

Laboratory parameters suggestive of nephrotic syndrome in our index child

| Investigations | Values on Day 3 of hospital stay |

|---|---|

| Serum total protein (g/dl) | 4.1 |

| Serum albumin (g/dl) | 2.2 |

| Blood urea (mg/dl) | 15 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.38 |

| Serum cholesterol (mg/dl) | 415 |

| Urine routine examination | Albumin 4+ RBC—absent Casts—absent |

The child was delivered by normal vaginal delivery with no perinatal complications. There was no significant illness or hospitalizations prior to the present illness. There was no family history of renal disease or any similar illness in the family.

After admission, we continued steroids (2 mg/kg/day) and stopped furosemide. The child continued to have persistent loose stools with high purge rate. A possibility of persistent osmotic diarrhoea was proffered. Therefore, the child was kept on reduced lactose diet following which loose stools became passive and was gradually put on normal diet.

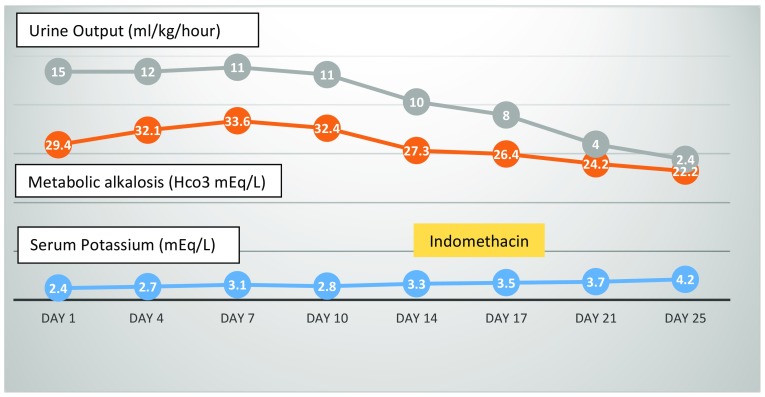

During the entire hospital stay, she had polyuria with urine output of around 10–12 ml/kg/h, episodes of hypotensive shock, hypokalemia and metabolic alkalosis. Further investigations also revealed hypomagnesemia and hypercalciuria. Furosemide-induced tubular dysfunction was considered (Table 2). Urine replacement and potassium correction was initiated. Since the hypotensive episodes continued she was started on oral indomethacin (2 mg/kg/day). The child promptly improved with urine output of 2 ml/kg/h on day 3 of indomethacin and normal serum potassium level. Subsequently, indomethacin was stopped on day 6. There was no recurrence of either polyuria or hypokalemia in the child and was discharged (Fig. 1). At 1 month of follow up, she was in remission with normal urine output and serum potassium level.

Table 2.

Biochemical characteristics suggestive of tubular dysfunction in our index child

| Investigations | Day 3 of hospital stay | Day 4 of hospital stay | Day 5 of hospital stay |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum sodium (mEq/L) | 137 | 139 | 140 |

| Serum potassium (mEq/L) | 2.1 | 3.3 | 3.1 |

| Serum chloride (mEq/L) | 110 | 115 | 112 |

| Serum magnesium (mg/dl) | 1.8 | 1.2 | 1.9 |

| Serum calcium (mg/dl) | 7.2 | 6.9 | 7.9 |

| Serum phosphorous (mg/dl) | 1.7 | 2.5 | 3.9 |

| Urine electrolytes | |||

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 73 | 55 | |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 14.9 | 20.6 | |

| Chloride (mEq/L) | 89 | 100 | |

| 24 h urinary calcium (mg/kg/day) | 4.1 | ||

| Venous blood gas | |||

| pH | 7.498 | 7.501 | 7.51 |

| Hco3 (mEq/L) | 29.4 | 32.1 | 33.6 |

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of changing trend of urine output, metabolic alkalosis and serum potassium versus days of hospital stay. The yellow shaded area is the duration when indomethacin therapy was given

Discussion

Nephrotic syndrome clinically presents with edema, which when significant needs anti-diuretic agents. Of all diuretics, furosemide is the most commonly used. However, the complications of volume depletion, electrolyte disturbances and metabolic alkalosis are well known [5]. Our case reiterates an important adverse effect of furosemide. The pseudo-bartter distal tubular dysfunction characterized by hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis, hypercalciuria and hypomagnesemia without significant elevation of serum creatinine was documented. It is possible that individual sensitivity, genetic background, dose and duration of furosemide administration and associated risk factors such as hypoalbuminemia, malnutrition could have contributed to the tubular dysfunction [4, 6].

The frequency, dosage and duration of furosemide-induced bartter like syndrome varies widely [3, 4]. The reported incidence is approximately 4.5%. It has been seen that furosemide administered at standard clinical dose for more than 10 days can cause immediate potassium and calcium wasting [4]. This bartter-like syndrome resolves within a period of few days to weeks following discontinuation of the drug. Appropriate potassium supplementation with discontinuation of furosemide form the core steps in therapy [7, 8].

Further, our case emphasizes a fact that furosemide-induced bartter like syndrome can be managed with a short course of prostaglandin synthesis inhibitor especially in severe cases where episodes of hypotension occurs even with urine and potassium replacement. Studies in rats have suggested that COX-2 derived prostanoids like rofecoxib-attenuated furosemide-induced diuresis, saluresis and renin activation [9]. We used indomethacin as there are case reports of its use [10, 11].

Moreover, this case also suggests that prolonged furosemide intake may result in elevated prostaglandin levels in renal parenchyma with resultant tubular dysfunction, much similar to that which is seen in inherited bartter syndrome [12]. Besides, the fact that symptoms in our child did not recur following stoppage of prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors signify the transient nature of tubular dysfunction and electrolyte abnormalities which are typical features of furosemide induced bartter like syndrome [4].

In conclusion, this case highlights the fact that prolonged furosemide administration can result in tubular dysfunction with features of bartter like syndrome. Along with discontinuation of the drug with potassium replacement, a short course of prostaglandin synthesis inhibitor can be used.

Funding

None.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

Due permission from the Departmental Review Board was taken.

Informed consent

Taken.

References

- 1.Keller E, Hoppe-Seyler G, Schollmeyer P. Disposition and diuretic effect of furosemide in the nephritic syndrome. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1982;32(4):442–449. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1982.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rane A, Villeneuve JP, Stone WJ, Nies AS, Wilkinson GR, Branch RA. Plasma binding and disposition of furosemide in the nephritic syndrome and in uremia. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1978;24(2):199–207. doi: 10.1002/cpt1978242199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colussi G, Rombolà G, Airaghi C, De Ferrari ME, Minetti L. Pseudo-Bartter’s syndrome from surreptitious diuretic intake: differential diagnosis with true Bartter’s syndrome. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 1992;7:896–901. doi: 10.1093/ndt/7.9.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Numabe A, Ogata A, Abe M, Takahashi M, Kono K, Arakawa M, Ishimitsu T, Ieiri T, Matsuoka H, Yagi S. A case of pseudo-Bartter’s syndrome induced by long-term ingestion of furosemide delivered orally through health tea. Nihon Jinzo Gakkai Shi. 2003;45:457–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vasudevan A, Mantan M, Bagga A. Management of edema in nephrotic syndrome. Indian Pediatr. 2004;41(8):787–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schepkens H, Hoeben H, Vanholder R, Lameire N. Mimicry of surreptitious diuretic ingestion and the ability to make a genetic diagnosis. Clin Nephrol. 2001;55:233–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruisz, et al. Furosemide-induced severe hypokalemia with rhabdomyolysis without cardiac arrest. BMC Women’s Health. 2013;13:30. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-13-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Unwin RJ, Capasso G. Bartter’s and Gitelman’s syndromes: their relationship to the actions of loop and thiazide diuretics. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006;6:208–213. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kammerl MC, Nüsing RM, Richthammer W, Krämer BK, Kurtz A. Inhibition of COX-2 counteracts the effects of diuretics in rats. Kidney Int. 2001;60(5):1684–1691. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sasaki H, Kawasaki T, Yamamoto T, Ninomiya H, et al. Pseudo-Bartter’s syndrome induced by surreptitious ingestion of furosemide to lose weight: a case report and possible pathophysiology. Nihon Naibunpi Gakkai Zasshi. 1986;62(8):867–881. doi: 10.1507/endocrine1927.62.8_867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sasaki H, Okumura M, Kawasaki T, Kangawa K, Matsuo H. Indomethacin and atrial natriuretic peptide in pseudo-Bartter’s syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1987;316(3):167. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198701153160314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seyberth HW, Koniger SJ, Rascher W, Kuhl PG, Schweer H. Role of prostaglandins in hyperprostaglandin E syndrome and in selected renal tubular disorders. Pediatr Nephrol. 1987;1:491–497. doi: 10.1007/BF00849259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]