Abstract

Organizational health literacy is described as an organization-wide effort to transform organization and delivery of care and services to make it easier for people to navigate, understand, and use information and services to take care of their health. Several health literacy guides have been developed to assist healthcare organizations with this effort, but their content has not been systematically reviewed to understand the scope and practical implications of this transformation. The objective of this study was to review (1) theories and frameworks that inform the concept of organizational health literacy, (2) the attributes of organizational health literacy as described in the guides, (3) the evidence for the effectiveness of the guides, and (4) the barriers and facilitators to implementing organizational health literacy. Drawing on a metanarrative review method, 48 publications were reviewed, of which 15 dealt with the theories and operational frameworks, 20 presented health literacy guides, and 13 addressed guided implementation of organizational health literacy. Seven theories and 9 operational frameworks have been identified. Six health literacy dimensions and 9 quality-improvement characteristics were reviewed for each health literacy guide. Evidence about the effectiveness of health literacy guides is limited at this time, but experiences with the guides were positive. Thirteen key barriers (conceived also as facilitators) were identified. Further development of organizational health literacy requires a strong and a clear connection between its vision and operationalization as an implementation strategy to patient-centered care. For many organizations, becoming health literate will require multiple, simultaneous, and radical changes. Organizational health literacy has to make sense from clinical and financial perspectives in order for organizations to embark on such transformative journey.

Keywords: health literacy, organizations, quality improvement, patient-centered care

Introduction

Organizational health literacy (OHL), described as an organization-wide effort to make it easier for people to navigate, understand, and use information and services to take care of their health,1,2 has emerged amid the discussions about the role of healthcare systems in addressing the challenge of predominantly low levels of health literacy in populations.3-6 Research demonstrates that health systems remain less responsive than needed to the issue of low health literacy.7-9 Lack of involvement of patients in decision making; unintentional nonadherence to treatments and medications; difficulties with informed consent, patient-provider communication, and discharge instructions10-15; and increasing rates of emergency care, hospitalizations, and readmissions16-18 have been reported for patients with limited health literacy. The vicious cycle of negative health outcomes and limited health literacy is perpetuated by impossible to navigate healthcare systems and difficult to understand communication tools.13,19,20

Proponents of OHL emphasize that challenges experienced by patients in the care process can only be understood within the organizational context of care because patients’ ability to understand health information and to navigate the care-seeking process is related to the demands that healthcare systems place on them.21,22 Similarly, challenges experienced by healthcare organizations and health systems could be understood within the organizational context of care because the design and delivery of quality care should be related to the demands and expectations that patients and families place on healthcare organizations.23 The organizational context where care is provided (eg, simplified interface with healthcare procedures, easy-to-understand information) could compensate for patients’ limited health literacy24 and could also present an opportunity for improvement for healthcare organizations.25 Therefore, patients’ needs may be better met and quality of care could be improved if healthcare organizations transformed to health literacy responsive ones delivering care in a way that supports health literacy best practices and does not require advanced health literacy skills of the patients.26-28

With a prima facie case for OHL established, there has been a steady rise in research and application of OHL in the past few years, for example, in the context of an active offer of health care to linguistic minorities,23 health-literate discharge practices,29 optimum designs and structures of health-literate healthcare organization,30,31 and barriers to and experiences with OHL.2,32 To assist organizations with their transition to OHL, a series of health literacy guides have been developed in the past decade. However, the content of these guides and their use have not been reviewed systematically to understand the scope of transformation to health-literate organization and its practical implications. In this article, we address this specific gap in knowledge by focusing on the following: (1) the attributes of OHL described in the guides, (2) the evidence for the effectiveness of the application of the guides, and (3) the barriers and facilitators to implementing OHL. Originally, we set out to review health literacy guides, but our initial search turned out literature about theoretical aspects of OHL and its operationalization. Intrigued by this finding, we added a question framed as, what theories and frameworks inform the concept of OHL?

With the understanding that the application of OHL requires a change in organizations’ practices and processes, we drew on the Model for Improvement33 and associated Plan-Do-Study-Act-based sequence to provide overall structure for the article and to organize our findings. The advantage of using the Model for Improvement is that it is highly adaptive and minimally prescriptive, and emphasizes empowerment, learning, and growth of knowledge among the users.33 The sequence for improvement built in the model includes 4 stages of change: developing a change, testing it, making it part of the routine, and disseminating it. The first 3 stages were adopted for this study.

We used an adaptation of the metanarrative review as a means for synthesizing a range of literature.34 This review provides unique insights into the extent and scope of research and implementation of OHL and discusses recommendations to improve the organization, quality, and delivery of healthcare. These findings have relevance for researchers, advocates, and professionals working to promote OHL, including healthcare administrators, and quality improvement specialists whose mandates include evaluation of quality of care and continuous quality improvement.

Methods

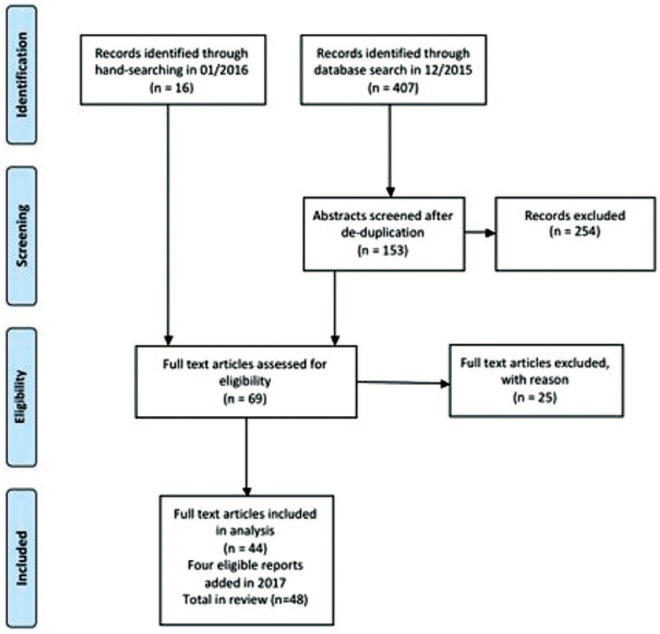

Drawing on principles of pragmatism, pluralism, and reflexivity of metanarrative review,34 a systematic search of literature was combined with narrative syntheses and analyses. A literature search in Medline (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), Healthstar (Ovid), and PubMed was performed in January 2016. Database searches were supplemented by bibliographic hand searches and gray literature. An initial search was conducted using 10 keywords (organization, leadership, planning, workforce, patient, engagement, communication, navigation, education, and health system) combined (using Boolean operators and, or) with the term health literacy. This produced a list of 48 eligible articles. Full texts of 15 of them were reviewed to help refine the search strategy, and a new search was performed. In October 2017, relevant reports published in 2016-2017 were identified and included accordingly. A detailed search strategy is presented in Table 1. Search results were exported to Mendeley reference manager software, version 1.17.11 and earlier, and duplicates were removed. The search results are shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Detailed Search Strategy Ovid (Medline) Platforma and Search Terms.

| Step | Searches |

|---|---|

| 1 | Health Literacy/og [Organization & Administration] |

| 2 | limit 1 to humans |

| 3 | (health literate adj3 (organi?ation* or care or healthcare or hospital* or service* or policy or policies or system or systems)).ti,ab. |

| 4 | (health literacy adj3 (organi?ation* or care or healthcare or hospital* or service* or policy or policies or system or systems)).ti,ab. |

| 5 | Organizations/ |

| 6 | Models, Organizational/ |

| 7 | Delivery of Healthcare/ |

| 8 | Health Policy/ |

| 9 | Policy Making/ |

| 10 | Organizational Culture/ |

| 11 | quality of healthcare/ |

| 12 | 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 |

| 13 | Health Literacy/ |

| 14 | 12 and 13 |

| 15 | Patient Participation/mt [Methods] |

| 16 | Patient Participation/td [Trends] |

| 17 | Patient engagement/td [Trends] |

| 18 | Health Communication/mt [Methods] |

| 19 | 12 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 |

| 20 | 13 and 19 |

| 21 | 1 or 3 or 4 or 20 |

Above search modified for PubMed, Embase, and PsycINFO.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they related to health literacy at organizational or system level and were published in English or French. No time limit, country, or study design restrictions were imposed. However, original research studies that provided details about methods and results were given preference. Each report was screened in 2 stages. In the first stage, titles and abstracts were reviewed for potential relevance. In the second stage, full texts were obtained for further evaluation and screened to determine eligibility.

A content analysis was performed, and selected articles were clustered by study topics into the following categories: (1) studies addressing the development of theory and concept of OHL, (2) health literacy guides developed to inform the transition from healthcare organization to health-literate healthcare organization, and (3) studies reporting on the application of health literacy guides. Our search also turned out 4 studies on measurement of OHL24,26 and related constructs.35,36 Because health literacy guides typically include an assessment portion, these studies were not included in the review.

The guides were scanned for attributes of OHL conceived as health literacy dimensions and quality improvement characteristics. To review and present findings about health literacy–related content, we drew on 6 dimensions of health literacy developed by the New Zealand Ministry of Health37 based on the attributes of health-literate organizations.1 The following health literacy dimensions were captured for each guide: access and navigation, communication, consumer involvement, workforce, leadership and management, and the needs of the population. The quality improvement characteristics were identified and adapted from a variety of relevant sources.33,38-43 The following quality improvement characteristics were recorded for each guide: forming teams, setting specific aims, assessment/gap analysis, establishing measures, communicating/raising awareness, developing health literacy improvement plan, testing changes, tracking progress, sustaining efforts, and scaling up.

Results

The database search, combined with reference tracking and gray literature, resulted in the initial identification of 423 relevant publications in 2016. Four more reports were identified and added in 2017 to update the content of this review. Based on the application of the inclusion criteria to the full texts, 48 publications were retrieved, of which 15 explicitly dealt with the theories and operational frameworks of OHL, 20 presented health literacy guides, and 13 addressed the implementation of OHL and the use of guides.

Theories and Operational Frameworks of OHL

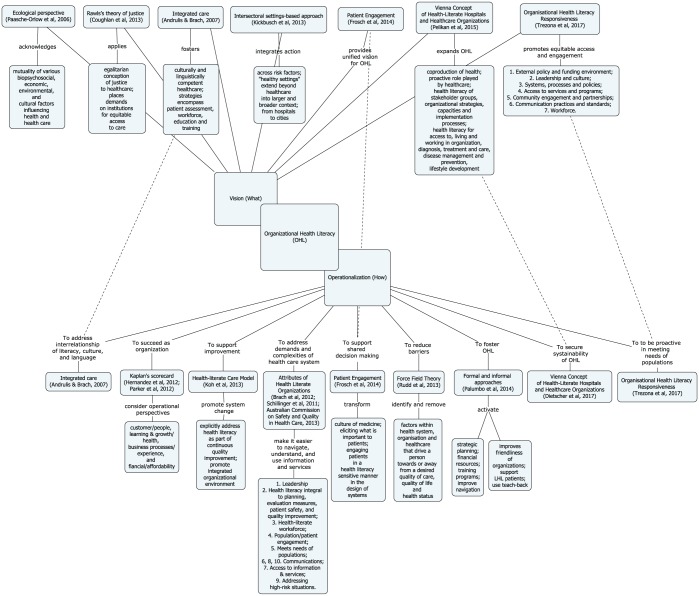

Fifteen included studies have been identified as conceptual papers on OHL. Figure 2 lists these papers and presents a conceptual map of OHL. From this overview, it became apparent that conceptual approaches to OHL focus on the “what” and the “how,” where the “what” represents theories that help create vision and the “how” proposes operational frameworks to support action on OHL. However, this division is not strict for 4 theories/frameworks that show an overlap between the “what” and the “how” (described by dotted lines in Figure 2). While we attempted to depict chronological development of theories and frameworks in Figure 2, they are not always described in that order below.

Figure 2.

Conceptual map of theories and operational frameworks of OHL.

Note. OHL = Organizational health literacy.

The “What” of OHL

Seven theories have been identified (Figure 2). OHL is envisioned as a multifaceted issue, notably as an issue of population health, public health, responsive practice, and cultural competence. From an ecological perspective,44 limited health literacy is viewed as a vulnerability that coexists and interacts with other social vulnerabilities, and that interventions addressing an array of influences on peoples’ lives are needed. The Rawls’s theory of justice applies egalitarian concepts of justice to health care; that is, each person should have equal rights to healthcare services and their delivery.45 The Rawls’s theory is aligned with a proposition for an “integrated care,”46 which seeks to integrate health literacy and cultural competence. The authors argue that separation of health literacy from cultural competence forces healthcare providers to choose the former or the latter in the process of care. When used in isolation, health literacy or cultural competence cannot improve communication, service delivery, quality of care, and health outcomes on their own.46 The idea of integration is further explored in a settings-based approach of “health literacy–friendly and healthy settings,”47 where health literacy is extended into a broader context, from healthy hospitals to healthy cities. The authors argue that such approach could address limited health literacy broadly and across multiple risk factors, and is likely to be successful.47

Frosch and Elwyn48 propose a “unified” vision of health literacy with patient engagement to support patient-centered and responsive health care. This vision places health literacy in the broader movement of participatory medicine.49 The authors argue that health systems are responsible for leveraging both infrastructure and various strategies to effectively engage patients at all levels of health literacy throughout the care journey.48 To realize this vision, health systems must engage patients in the design of services that serve them, elicit what is important to them, and ensure that care is integrated in a way that serves patients’ needs.48

A vision of OHL as a complex phenomenon has been developed in 2 recent frameworks, the Vienna Concept of Health-Literate Hospitals and Healthcare Organizations (V-HLO)50 and the Organizational Health Literacy Responsiveness (Org-HLR) framework.51 In V-HLO, Pelikan and Dietscher50 present a broader understanding of health literacy as coproduction of health, quality, and safety; health promotion; and “healthy settings.” Similar to Kickbusch et al,47 authors of V-HLO also call for the wider application of health literacy beyond health care. The V-HLO focuses on health literacy of patients, healthcare providers, organizations, and populations. In Org-HLR, one of the first empirically developed frameworks of OHL, Trezona and colleagues51 conceptualize health literacy as an issue of healthcare responsiveness. The authors argue that a system-level effort is required to address the issue of limited health literacy and that there is a need for organizations to be proactive in meeting community needs, that is, be responsive.51

The Org-HLR framework highlights the interconnection between leadership and culture, systems, processes and policies, access to services and programs, community engagement and partnership, communication practices and standards, and workforce. In addition to providing the vision, both V-HLO and Org-HLR focus on developing organizational capacities, structures, and processes to support action on health literacy52 and are reviewed below as the “how” of OHL.

The “how” of OHL

Nine operational frameworks of OHL have been identified (Figure 2). Several distinct but interconnected disciplines including organizational behavior, healthcare management, implementation science, and quality improvement underpin operationalization of OHL. While frameworks vary in their aim (eg, reduce barriers, secure sustainability) and the scope of application (eg, patient, program, organization, and health-system level), they all target organizations’ capacity to design and deliver health-literate care.

The first notions of OHL were linked to the Kaplan and Norton balanced scorecard,53-55 the framework presented in the Crossing the Quality Chasm report,56 and also to the chronic care model.53,57 The new Health Literate Care Model27 was designed to support improvement strategies that promote comprehensive system change, encourage transparency concerning quality problems, and provide incentives for delivering high-quality care. In this model, staff take on new roles, such as scheduling interpreter services in advance, facilitating patient education during group visits, and calling patients to confirm their understanding of laboratory results or complex medication regimens.27 The model relies on effective patient engagement to design and deliver high-quality health-literate care, and by doing so, this model also operationalizes the vision of patient engagement described by Frosch and Elwyn.48

The 10 attributes of health-literate organizations1 are based on the OHL concept developed by Schillinger and Keller.58 These attributes help healthcare organizations embrace health literacy by focusing on written and spoken communication, addressing difficulties in navigating facilities and complex systems, initiating and spreading health-literate practices, establishing a health literacy workforce and supporting structures, expanding patient and family input, establishing policies and monitoring compliance, addressing population health, and ultimately shifting the culture of the entire organization.1 The 10 attributes have been criticized for being developed inductively and for lacking theoretical backing.50 Despite limitations, the 10 attributes provided intellectual foundation to at least 2 other action frameworks, the above mentioned V-HLO52 and Org-HLR.51 The V-HLO aims at sustainability of OHL by targeting the development of organizational capacities to address specific action areas, including adequate access to health care, meaningful engagement in the process of care, successful disease management, disease prevention, and health promotion at population level.52 The Org-HLR operationalizes health literacy responsiveness as a system-level action built on intersectoral partnerships to enable effective coordination and integration of care and services, and system navigation.51 According to the authors, the Org-HLR can have a wide range of application from quality improvement and organizational development to health system reforms that promote equity and public participation in decisions regarding their health and well-being.51

Kurt Lewin’s force field theory is proposed as a strategy to identify and remove barriers to information, to services, and to care to improve health literacy.59 Applied in change management, Lewin’s analysis can help identify factors within the health system and/or organization that drive a person toward or away from a desired quality of care, quality of life, and health status.

Approaches taken by organizations to foster OHL have been categorized as formal and informal.28 Formal approaches, thought to be more effective than informal approaches, are related to systemic integration of health literacy (eg, infrastructure, processes). In contrast, informal approaches relate to healthcare professionals’ inclination to informally support patients. Informal approaches are used more commonly than formal approaches and help counterbalance the lack of health literacy orientation at organizational level, that is, lack of formal approaches at organization level.28

Guides and Toolkits for OHL

Twenty health literacy guides were identified (Table 2). Guides vary in their scope (single- to multiple-issue) and context to which they apply. The majority of guides were developed for healthcare organizations in general; 6 are specialized for primary care practices, hospitals, and pharmacies, and one is designed to support health-literate nursing practices (Table 2). Most guides combine an assessment of health literacy barriers and an action plan for improving OHL. Guides were evaluated based on their health literacy dimensions and quality improvement characteristics.

Table 2.

Descriptive Characteristics of OHL Guides.

| Author/guide | Year | Country | Objective | Healthcare sector | Focus | Health literacy elements included | Score (Y/N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rudd & Anderson | 2006 | USA | To assist leadership and staff to consider health literacy environment of health care facilities | Hospitals or health centers | Approach for analyzing health literacy–related barriers to health care access and navigation and an action plan | 1. Navigation; 2. Print communication; 3. Oral exchange; 4. Technology; 5. Policies & protocols | Y |

| The Joint Commission | 2007 | USA | To improve health literacy, reduce communications-related errors, and better support the interests of patients and providers of care | Healthcare delivery organizations | Recommendations for improving communications | 1. Make communications organizational priority to protect safety of patients; 2. Address patients’ communication needs across continuum of care | N |

| Jacobson (A Pharmacy Health Literacy Assessment Tool User’s Guide) | 2007 | USA | To capture critical perspectives about pharmacy health literacy as a step for quality improvement in organizations that serve individuals with limited health literacy | Outpatient pharmacies of large, urban, public hospitals | Pharmacy health literacy assessment | 1. A pharmacy assessment tour; 2. A survey for pharmacy staff; 3. A guide for focus groups with pharmacy patients | Y |

| Peters, 2008 (Health Literacy Audit) | 2008 | Canada | Identify patients’ health literacy needs, reaffirm practices done well, give suggestions for improving health information | Healthcare delivery organizations | Checklists to help health organizations and providers choose more literacy-friendly methods of communicating with patients | 1. Advertising; 2. Health facility setting; 3. Admission procedures; 4. Appointments; 5. Discharge procedures; 7. Patient education; 8. English as an additional language and cultural sensitivity; 9. Clear print materials; 10. Staff and volunteer training | Y |

| Deasy et al, 2009 (Literacy Audit for Healthcare Settings) | 2009 | Ireland | To address literacy issues in healthcare settings | Healthcare delivery organizations | Assessment and best practice guidelines for implementation | 1. Literacy awareness; 2. Navigation–finding your way around; 3. Print materials; 4. Visuals; 5. Verbal communication; 6. Websites and kiosks; 7. Health literacy summary sheet | Y |

| Emory University and America’s Health Insurance Plans | 2010 | USA | To evaluate the health literacy friendliness of health insurance plans | Healthcare organizations that have health insurance plans | Self-assessment tool helps identify areas in need of improvement to enhance health literacy at organizational level | 1. Printed member information; 2. Web navigation; 3. Member services/verbal communication; 4. Forms; 5. Nurse call line; 6. Member case/disease management | N |

| Rudd et al, 2010 (The Health Literacy Environment Activity Packet First Impressions & Walking Interview) | 2010 | USA | To address physical navigation as part of the creation of the Health Literacy Environment of a Healthcare Facility | Hospitals and health centers | Assessment of physical navigation to and within the healthcare organization | First impressions (phone call, website review, and walk to facility’s entrance); Walking interview (navigation, observation, reflections, use of signs, feedback) | N |

| DeWalt, 2010 (Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit) | 2010 | USA | To provide step-by-step guidance and tools for assessing your practice and making changes so you connect with patients of all literacy levels | Primary care practices | Assessment and implementation strategies to make changes to connect with patients of all health literacy levels | 1. Spoken communication; 2. Written communication; 3. Self-management and empowerment; 4. Supportive systems | NR |

| Strickland (A Health Literacy Tool Kit for Healthcare Providers: Improving Communication With Clients) | 2011 | Canada | To provide practical tools, applications, and resources for communication with clients and encourage integration of user-friendly modules into training curriculum of healthcare providers | Healthcare delivery and social services organizations | Practical tools, applications, and resources for communication with clients | 1. Introduction to health literacy; 2. Communicating with your clients; 3. Plain language and clear design | NR |

| Ten Attributes of Health Literate Healthcare Organizations | 2012 | USA | To describe 10 attributes of health-literate healthcare organizations | Healthcare delivery organizations | Assessment and implementation strategies to become a health-literate organization | 1. Leadership; 2. Integration of health literacy; 3. Workforce; 4. Public/patient engagement; 5. Needs of populations; 6. Communication with providers; 7. Access; 8. Health information; 9. Care transitions; 10. Communication about payment | N |

| Thomacos & Zazryn (Enliven Organisational Health Literacy Self-assessment Resource) | 2013 | Australia | To provide health and social service organizations with a self-assessment tool to guide and inform their development as health-literate organizations | Health and social service organizations | Assessment and implementation strategies to become a health-literate organization | 1. Leadership; 2. Integration of health literacy; 3. Workforce; 4. Public/patient engagement; 5. Needs of populations; 6. Communication with providers; 7. Access; 8. Health information; 9. Care transitions; 10. Communication about payment | Y |

| Dodson et al (Health Literacy Toolkit for Low- and Middle-Income Countries) | 2014 | WHO | To assist organizations and governments to incorporate health literacy responses into practice, service delivery systems, and policy | Health systems in low- and middle-income countries | Information sheets and recommendations for action to assess health literacy needs of communities and strengthen health systems | Promotes the Ophelia approach to optimizing health literacy based on the identification of community health literacy needs, and the development and testing of potential solutions | N |

| Abrams et al (Building Health Literate Organizations: A Guidebook to Achieving Organizational Change) | 2014 | USA | To help organizations of any size become health-literate healthcare organizations | Healthcare delivery organizations | A change package to transform care environment, culture, policies, and procedures to delivery health-literate care in a health-literate organization | 1. Engaging leadership; 2. Preparing the workforce; 3. The care environment; 4. Involving populations served; 5. Verbal communication; 6. Reader-friendly materials; 7. Case study | N |

| Brega et al (Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit, Second Edition) | 2015 | USA | To support primary care practices in addressing shortages in health literacy | Primary care practices | A change package to reduce the complexity of health care, increase patient understanding of health information, and enhance support for patients of all health literacy levels | 1. Spoken communication; 2. Written communication; 3. Self-management and empowerment; 4. Supportive systems | N |

| Cifuentes et al (Implementing the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit: Practical Ideas for Primary Care Practices) | 2015 | USA | To offer implementation advice based on experiences of 12 primary care practices from the Demonstration of Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit | Primary care practices | A companion to the AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit | 1. Spoken communication; 2. Written communication; 3. Self-management and empowerment; 4. Supportive systems | N |

| French (Transforming Nursing Care Through Health Literacy ACTS (assess, collaborate, train, and survey)) | 2015 | USA | To transform nursing care through health literacy ACTS educate patients and advocate for practical improvements in healthcare systems accessibility | Nursing care | An informal practice guideline based on universal precautions and health literacy to healthy-literate nursing care | ACTSs | N |

| The New Zealand Ministry of Health (Health Literacy Review: A Guide) | 2015 | New Zealand | To help carry out a health literacy review and build a health-literate organization | Healthcare delivery organizations | A change package to conduct health literacy review and develop action plan | 1. Leadership and management; 2. Consumer involvement; 3. Workforce; 4. Meeting the needs of the population; 5. Access and navigation; 6. Communication | N |

| The Vienna Health Literate Organizations Instrument | 2015 | Austria | To define and assess OHL | Healthcare delivery organizations | An assessment tool to assess conformity to the standards of OHL | Assessment against 9 standards, 22 substandards, including but not limited to having management policy and organizational structures for health literacy, developing materials and services in participation with relevant stakeholders, provide health-literate navigation and access | N |

| Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, (Making Health Literacy Real: The Beginnings of My Organization’s Plan for Action) | ND | US | To help organizations get started in developing your own plan to change organizational and professional practices to improve health literacy | Healthcare delivery organizations | Assessment and plan of action | 1. Identifying my advocates; 2. Getting buy-in; 3. Commitment to planning; 4. Honest assessment; 5. Consider barriers & solutions; 6. Developing your action plan; 7. Next steps; 8. Planning resources | N |

| Clinical Excellence Commission (Health Literacy Guide) | ND | Australia | To assist health services by providing practical strategies to address health literacy barriers for patients | Healthcare delivery organizations | Assessment | 1. Gap Analysis; 2. Recruiting advisors; 3. Literacy and communication; 4. Numeracy; 5. Wayfinding; 6. Quick start check list | N |

Note. OHL = organizational health literacy; AHRQ = Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; ACTS = assess, collaborate, train, and survey; NR - Not Reported.

Health literacy dimensions

Although few guides address all 6 health literacy dimensions, communication and access and navigation are consistently included in all guides (Table 3). Access and navigation refer both to the physical environment and the services provided by the organization. Services do not only include health care, but also telephone systems and print materials—such as medical history forms, directives, and consent forms that are accessible and are easy to use.

Table 3.

Health-Literate Dimensions of OHL Guides.

| Guides | Dimensions of health-literate organizations |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access and navigation | Communication | Consumer involvement | Workforce | Leadership and management | Meeting needs of population | |

| Rudd, 2006 (The Health Literacy Environment of Hospitals and Health Centers: Making Your Healthcare Facility Literacy Friendly) | Access to health literacy-friendly telephone system; physical environment. | Print communication; oral Exchange | Orientation and training in health literacy, oral exchange with patients; English for speakers of other languages courses | Assistance with medical records, pharmacy, translation, and so on | ||

| The Joint Commission, 2007 (What Did the Doctor Say? Improving Health Literacy to Protect Patient Safety) | Wayfinding (especially with consideration for patients with Limited English Proficiency) | Effectiveness of communication among caregivers | Training to recognize and respond to patients with literacy and language needs | Create culture of safety and quality; ensure easy access to services | Improve accuracy of patient identification; medication reconciliation; self-management; care transitions; use medical interpreters | |

| Jacobson, 2007 (A Pharmacy Health Literacy Assessment Tool User’s Guide) | Promotion of services; physical environment | Print materials; clear verbal communication | Requesting feedback during assessment | Assessment of workforce | Assessment of care processes | |

| Peters, 2008 (Health Literacy Audit) | Physical environment | Advertising; clear print materials | Staff and volunteer training (eg, use of plain language, easy-to-read materials, use of readability tool) | Admission; appointments; discharge; patient education; English as an additional language and cultural sensitivity | ||

| Deasy et al, 2009 (Literacy Audit for Healthcare Settings) | Wayfinding | Print materials; visuals; verbal communication; websites and kiosks | Health literacy awareness training | |||

| Emory University and America’s Health Insurance Plans, 2010 (Health Plan Organizational Assessment of Health Literacy Activities) | Web navigation | Printed information; verbal communication; forms; nurse call line; case/disease management | Training health communication (embedded in nurse call line; case/disease management) | Nurse call line; case/disease management | ||

| Rudd, 2010 (The Health Literacy Environment Activity Packet First Impressions & Walking Interview) | Wayfinding | Printed words, internal and external signs, plain language, translation (as part of Walking Interview) | ||||

| DeWalt, 2010 (Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit) | Access to health-literate telephone system; signs, physical environment, and navigation | Verbal and print communication; use of teach-back method | Use of teach-back method; follow up with patients; patients’ feedback to improve self-management | Health literacy awareness training | Commit to health literacy universal precautions | Language assistance; use of teach-back; follow up with patients; “Brown Bag review” of medicines; referral for nonmedical services |

| Strickland, 2011 (A Health Literacy Tool Kit for Healthcare Providers: Improving Communication With Clients) | Communicating with your clients; plain language and clear design | |||||

| Brach, 2012 (Ten Attributes of Health Literate Healthcare Organizations) | Easy access to health information and services; assistance with navigation | Interpersonal communications; print, audio-visual, and social media content | Involved in design, implementation, and evaluation of health information and services | Training and involvement in monitoring progress | Make health literacy integral to mission, structure, and operations | Practices allowing to avoid stigmatization, addressing high-risk situations, medication reconciliation, innovations, and technology |

| Thomacos & Zazryn, 2013 (Enliven Organisational Health Literacy Self-assessment Resource) | Easy access to health information and services; assistance with navigation | Interpersonal communications; print, audio-visual, and social media content | Involved in design, implementation, and evaluation of health information and services | Training and involvement in monitoring progress | Make health literacy integral to mission, structure, and operations | Practices allowing to avoid stigmatization, address high-risk situations, medication reconciliation, innovations, and technology |

| Dodson, 2014 (Health Literacy Toolkit for Low- and Middle-Income Countries) | Access to services | Access to information | Co-creation of health literacy interventions | Identifying and addressing the skills and limitations of local communities | ||

| Abrams, 2014 (Building Health Literate Organizations: A Guidebook to Achieving Organizational Change) | Shame-free care environment | Verbal communication; reader friendly materials | Seek patient stories; ask for feedback on written materials; establish Patient and Family Advisory Council; create Volunteer Health Literacy Work Group | Health literacy training; raise awareness about health literacy and change behaviors using traditional methods, marketing strategies and coaching | Engage leadership; establish organization’s culture that integrates health literacy in its mission, vision and operations | Shame-free care environment; self-management support |

| Brega, 2015 (AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit, Second Edition) | Access to a health-literate telephone system; language access issues; signs, physical environment, and navigation | Spoken & written communication; use of teach-back method | Use of teach-back method; follow up with patients; patients’ feedback on written materials | Raising awareness and training staff | Dedicate team and health literacy team leader; assure senior management accountability and engagement | Use of teach-back; follow up with patients; review of medicines; referral for nonmedical services |

| Cifuentes et al, 2015 (Implementing the AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit: Practical Ideas for Primary Care Practices) | Implement health-literate telephone access; address language differences; improve signs, physical environment, and navigation | Assess, select, and create easy-to-understand materials; map workflow for use of health education materials; use of teach-back | Members of the QI & health literacy team; use of teach-back method; follow up with patients; patients’ feedback or survey | Educational sessions and training opportunities for staff | Dedicate team and health literacy team leader | Use of teach-back; follow up with patients; review of medicines; referral for nonmedical services |

| French, 2015 (Transforming Nursing Care Through Health Literacy ACTS) | Assess health environments | Assess health materials; use of Teach 3 or teach-back | Use of Teach 3 or teach-back; review or modification of patient educational materials | Training with peers to implement health literacy competencies training | Assess patient concerns; match relevant resources to patient knowledge gaps and needs; use of Teach 3 or teach-back | |

| The New Zealand Ministry of Health, 2015 (Health Literacy Review: A guide) | Assess health environment and processes; assure that consumers easily find and engage with health and related services | Identify information needs; help consumers find and engage with services | Design, development, and evaluation of organization’s values, vision, structure, and service delivery | Feedback about perceptions and practices relevant to health literacy; support of effective health literacy practices; health literacy training | Include health literacy in strategic and operational plans | Service delivery assures that consumers are able to participate and have their health literacy needs identified and met |

| The Vienna Health Literate Organizations Instrument | Access to a health-literate internet and telephone system; signs, physical environment, and easy-to-follow navigation system | Develop materials and services in participation with relevant stakeholders; apply health literacy principles in communication with patients | Develop materials and services in participation with relevant stakeholders | Qualify staff for health-literate communication with patients; improve the health literacy of staff | Establish management policy and organizational structures for health literacy | Patients (and significant others) are supported to improve health literacy for disease-related self-management and healthy lifestyles |

| Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, n.d. (Making Health Literacy Real: The Beginnings of My Organization’s Plan for Action) | Assess physical environment | Health information forms & fact sheets; verbal communication | Identify champions, allies, workgroup members | Identify champions, allies, workgroup members | Gain endorsement from senior leadership; “vet” health literacy improvement plan | |

| Clinical Excellence Commission, n.d. (Health Literacy Guide) | Wayfinding | Develop and assess patient information; improve communication, understanding and use of information; signage | Recruit consumer advisors | Health literacy training for reception, admissions, and hotel services | Use teach-back; assist with medications (how to take, explain new medications, etc) | |

Verbal and written communication is included in all activities undertaken by a health-literate organization. A variety of tools and methods, such as the use of plain language, teach 3, and teach-back methods, are recommended to improve the delivery of health information and to assure its comprehensibility, understanding, and use. 35,60-62 For organizations serving minority populations who experience linguistic barriers in the process of care, specific practices are recommended for assessing barriers and implementing language-assistance needs of consumers, identifying the organization’s capacity for language-assistance services,63,64 and building “culture-proofing” into the process of information production.65

A great number of guides include recommendations for improvements in specific care processes such as admission and discharge, disease- and self-management practices, medication reconciliation, and creation of shame- and stigma-free care environments (Table 3). Recent guides recommend consumer involvement in OHL assessment, quality improvement efforts, development of education materials, and service redesign.14,37,60,61,66 The role of workforce has also expanded to include active participation both in the process of care and in creation of a health-literate environment.1,37,63,67 For staff to be effective contributors to the organization’s health-literate effort, the Vienna Health Literate Organizations Instrument (V-HLO-I) targets improvement of health literacy skills of staff to help them manage job-related health risks and also adopt healthy lifestyles.52 The guides emphasize the critical role leadership plays in the integration of health literacy in an organization’s vision, mission, and strategic planning.14,37,60,67,68

Quality improvement characteristics

Elements of quality improvement methods are found in every reviewed guide, although those developed since 2010 consistently link health literacy to safety and quality improvement (Table 4). Two elements, health literacy assessment and development of action or improvement plans, are commonly recommended as part of health-literate actions. Several guides recommend using the Model for Improvement33 to inform the development and implementation of health literacy improvement plans.14,60,68,69 Assessments help identify strengths, barriers, and opportunities for improvement, and also focus on promotion of services (how well services are advertised and how “user-friendly” the physical environment is to facilitate access and navigation) and provision of clear print and verbal communication. Some guides also include review of policies and protocols, specific professional practices, and technologies.14,60,61,70 Assessments often consist of a facility tour conducted by staff, partner organizations, or external auditors, and include staff survey and scoring.63-65,70,71

Table 4.

Quality Improvement Characteristics of OHL Guides.

| First author/guides | Form team | Set aims | Assess | Establish measures | Communicate, raise awareness | Develop action plan | Test changes | Track progress/sustain efforts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rudd, 2006 (The Health Literacy Environment of Hospitals and Health Centers: Making your Healthcare Facility Literacy Friendly) | • | • | ||||||

| The Joint Commission, 2007 (What Did the Doctor Say? Improving Health Literacy to Protect Patient Safety) | • | • | • | |||||

| Jacobson, 2007 (A Pharmacy Health Literacy Assessment Tool User’s Guide) | • | • | • | |||||

| Peters, 2008 (Health Literacy Audit) | • | |||||||

| Deasy et al, 2009 (Literacy Audit for Healthcare Settings) | • | • | ||||||

| Emory University and America’s Health Insurance Plans, 2010 (Health Plan Organizational Assessment of Health Literacy Activities) | • | |||||||

| Rudd, 2010 (The Health Literacy Environment Activity Packet First Impressions & Walking Interview) | • | |||||||

| DeWalt, 2010 (Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit) | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| Strickland, 2011 (A Health Literacy Tool Kit for Healthcare Providers: Improving Communication With Clients) | • | |||||||

| Brach, 2012 (Ten Attributes of Health Literate Healthcare Organizations) | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| Thomacos & Zazryn, 2013 (Enliven Organisational Health Literacy Self-assessment Resource) | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| Dodson, 2014 (Health Literacy Toolkit for Low- and Middle-Income Countries) | • | • | • | |||||

| Abrams, 2014 (Building Health Literate Organizations: A Guidebook to Achieving Organizational Change) | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |

| Brega, 2015 (AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit, Second Edition) | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| Cifuentes et al, 2015 (Implementing the AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit: Practical Ideas for Primary Care Practices) | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| French, 2015 (Transforming Nursing Care Through Health Literacy ACTS) | • | • | ||||||

| The New Zealand Ministry of Health, 2015 (Health Literacy Review: A Guide) | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| Dietscher & Pelikan, 2017 (The Vienna Health Literate Organizations Instrument) | • | |||||||

| Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, n.d. (Making Health Literacy Real: The Beginnings of My Organization’s Plan for Action) | • | • | • | • | • | |||

| Clinical Excellence Commission, n.d. (Health Literacy Guide) | • | • | • | • |

Actions for improvement are recommended in 2 broad areas in the guides: (1) communication and (2) organization of health care. Communication actions range from systemic improvements facilitating productive interactions (eg, adoption of universal precautions in all patient encounters) to targeted improvements in existing health information materials and forms using plain language and the languages commonly spoken by patients. Organization of health care includes a range of changes in structures and processes facilitating improvements in the navigation and design of services and programs, policies, protocols, procedures, and preparation of workforce to deliver health-literate care. These improvements also include both systemic (addressing the entire organization) and targeted improvements in specific procedures, such as referrals for a service, development of personal care plans, and use of patient portals. The guides often recommend using Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles to test changes before spreading them through the organization.14,37,60,68,72,73

Implementation of OHL

Thirteen reports published in 2008-2017 described the use of health literacy guides.2,28,32,74-83 The majority of these reports described the use of assessments of health literacy barriers75,78,81; few reports detailed implementation of OHL.2,80,83 Although these studies do not allow to comprehensively assess evidence of the effects of OHL and the application of the guides, they demonstrate that guides can facilitate action to remedy health literacy barriers,2,52,75,78 to adopt specific health-literate practices,2,80,83 and to understand the complexity of OHL and the factors influencing health-literate practices.2,74,78

Organizations commonly modified existing guides to local context2,83 and used 2 or more health literacy guides78,80 at the same time. A health literacy universal precautions toolkit14,60,73 was favored in chronic disease management,83 health promotion and disease prevention interventions84 and to inspire the adoption of system-wide policies and procedures across healthcare organizations.2

The use of assessment tools provided with the guides was regarded as a useful and feasible exercise to provide direction for improvement75,78,85; it required few organizational resources, and caused little to no interference with patient care.75 A particular guide, however, was perceived as complex with limited value.79 The use of health literacy guides could be enhanced if the guides had a clear relative advantage, were simple and adaptable, and if support with implementation was provided or barriers to OHL removed.79

Barriers and facilitators of OHL

Thirteen key barriers (conceived also as facilitators) were identified in literature detailing the use of health literacy guides, covering 3 broad themes: barriers 1 to 4 describe organizational and institutional culture and leadership; 5 to 10 relate to the design and planning of improvement interventions; and 11 to 13 refer to human resources (Table 5). For many organizations, becoming health-literate will require multiple, simultaneous, and radical changes.28,80 Although literature on this topic is scarce, existing reports suggest that systemic approach to addressing health literacy within healthcare organizations is lacking.28,76,82 Specifically, organizational commitment toward health literacy is weak and efforts to enhance OHL via policies, planning, and programs are inadequate.28,76 Due to the lack of awareness about health literacy and its impacts on health outcomes and sustainability of the health system, health literacy is not typically integrated into organizations’ mission, vision, and strategic planning.28,82 In contrast, some health literacy practices may be implemented by front line staff but may not be recognized as such due to the lack of familiarity with the concept of health literacy.78

Table 5.

Key Barriers to Organizational Health Literacy.

| 1 | Low priority of health literacy and related activities |

| 2 | Lack of commitment to health literacy |

| 3 | Limited or no buy-in from leadership |

| 4 | Becoming health-literate is not perceived advantageous |

| 5 | Lack of culture of change and innovation |

| 6 | No change champions in the organization |

| 7 | Not having procedures, policies, protocols supporting health-literate practice |

| 8 | Not having enough time |

| 9 | Lack of resources |

| 10 | Complexity of health literacy tools and guides |

| 11 | Ambiguity of roles among staff |

| 12 | Lack of training in health literacy |

| 13 | Lack of awareness about health literacy |

When there is support and interest in improving communications and the role of health literacy, organizations may not have a mechanism for staff to train and learn about health literacy.78 The presence of advocates for change is critical.2,32,79 However, their success depends greatly on support from the leadership. The existence of a management structure and a culture that supports innovation and quality improvement is regarded as essential.

Discussion

The results of this review highlight a variety of theories, operational frameworks, and implementation guides for OHL. Similar to health literacy, OHL appears to be a heterogeneous phenomenon86; literature reviewed for this analysis demonstrates that OHL is theorized and operationalized from many different perspectives. Theorization of OHL as a public health issue is consistent with recent research on health literacy within a broader public-health model.87 However, this perspective may be problematic for the vision and operationalization of OHL beyond public health. From a population health perspective, OHL is envisioned as an equity issue. Although equitable access to health care and services is necessary to avoid worsening of social disparities and lowering of health status,88 equity in health cannot be fixed exclusively at the level of health system; because health care is produced by society and unfair social arrangements outside of health care, equity remains the characteristic of the social system45 and should be addressed by attending to social determinants and structural inequities outside of health care.47 There is a practical implication to envisioning OHL from a population health perspective: It inevitably takes healthcare organizations into the broader sociopolitical context. This vision demands the visionaries and implementers of OHL to acknowledge that access to health care and services is not the only determinant of health89-92; lifestyle, education, social support, and the environment are at least as important but are unaccounted for in most OHL frameworks.

We identified 20 health literacy guides supporting transition to OHL. On one hand, such variety allows organizations to make informed decisions about which guide to select based on the best evidence available for their unique situation; on the other hand, such variety may lead to confusion about how to think of OHL and what guide to use to plan action. Fortunately, in spite of many differences, all guides focus on addressing shortages in health literacy by reducing the complexity of health care, increasing patient understanding of health information, and enhancing supports for patients at all levels of health literacy.

Health literacy guides, particularly recent ones, provide evidence-based recommendations and best practices to support health-literate actions; they include explicit quality improvement methods, and help build a business case for OHL. However, with the exception of few health literacy guides,52,60,73 most guides have not been tested for applicability in organizational practices, which calls to question their effectiveness. Most but not all guides include an assessment of health literacy barriers. Assessment and screening to measure OHL could potentially be conducted using validated measurement tools.26,52,24

A better alignment is needed between theorization of OHL as a population health issue and its operationalization from a quality management perspective. The concern is that quality improvement activities that bring about immediate improvement in healthcare delivery in particular settings for a group of patients93,94 may be insufficient as a strategy to improve health and ensure equity for all. Specific strategies described in health literacy guides are likely to improve navigation and patients’ understanding and use of health information in specific settings,60,70 but they are less likely to produce relevant and effective policies to promote a comprehensive system change.27,52

While theories and operational frameworks place OHL in broader contexts,50,95 movements,47,48 and integrated care,46-48,27 the guides (inadvertently) address OHL as a standalone issue. Healthcare organizations are under tremendous pressure to deliver on patient-centered care (PCC) and patient engagement, embrace innovations for integrated care, and lower costs of care while they are also overcoming a change fatigue.96-98 It would be difficult to interject OHL in the midst of ongoing changes without operationalizing it properly. For example, the connection between PCC and OHL often lacks operationalization in health literacy guides. PCC has been defined as “care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values.”56 Efforts to make the healthcare environment more responsive to patients’ needs, preferences, and values also fall in the realm of OHL. Taking this view, OHL can be considered the “how” of PCC, the strategy and the catalyst for building supportive culture, supportive systems, policies and practices, and an effective workforce.51 Others have previously equated OHL with PCC99 and suggested integrating health literacy into patient-centered models of care.100 Based on this, we make a recommendation that actions related to improving OHL be included under the umbrella of all organizational changes centered on PCC.

Challenges perceived as barriers for implementing OHL have been previously reported in literature on quality improvement in general.2,101-105 A recent study identified lack of time and funding as the most common barriers for integration and sustainability of OHL.32 Cultural change, whether organizational culture or culture of innovation, is an essential but perhaps the most elusive of all challenges related to OHL.78-80 For most organizations, shift to a comprehensive OHL would likely be a complex process unfolding over many years. Key factors that facilitate success in quality improvement initiatives, including supportive leadership, supportive external stakeholders and professional allegiances, ownership of changes, and subcultural diversity within healthcare organizations and systems,106,107 will likely facilitate successful transition from healthcare organization to health-literate healthcare organization.

It is not clear from this review whether propositions for the vision and operationalization of OHL align with the perspectives from which healthcare organizations and their staff are prepared to approach health literacy. It is clear, however, that OHL has to make sense from clinical and financial perspectives in order for organizations to embark on such transformative journey.53 Limited health literacy is a significant independent factor associated with increased healthcare utilization and costs.108,109 Meeting the needs of people with limited health literacy could produce savings of approximately 8% of total costs for this population.109 This suggests that interventions should be designed to remediate health literacy needs to reduce costs and a shift to OHL could be a step in the right direction to achieve it.

There are several limitations to this review. Due to time and cost considerations, only English- and French-language publications were reviewed. This, and a lack of relevant keywords in the indexes of search, may have led to the omission of some relevant reports. Furthermore, the generalizability of these results may be limited because the majority of studies included health literacy guides from the United States.

Conclusions

OHL is designed to help build a person-centered, evidence-based, and quality-driven health care. To support this mission, several guides have been developed and provide evidence-based recommendations and best practices to tackle the issue of limited health literacy. While familiarity with health literacy is lacking and the use of guides has been limited thus far, reported experiences with the use of the guides have been overwhelmingly positive. A variety of theories and operational frameworks of OHL have been (and continue to be) developed. To a knowledgeable user, this variety offers a choice of perspectives about OHL and a course of action to achieve it. With definition of health care changing and expanding to take into account the wider determinants of health,110,111 OHL has to acquire a new meaning and stretch beyond improving navigation, understanding, and use of information. It is imperative that conceptualizations of OHL continue to build on and include notions such as intersectoral collaboration and stakeholder empowerment as described in Org-HLR51 and V-HLO,52 respectively. Equated with PCC, OHL should be included under the umbrella of all organizational changes for person-centered care and tried as a strategy to improve health outcomes and quality of care and to contain and reduce the cost of care.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Elina Farmanova  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0339-5231

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0339-5231

References

- 1. Brach C, Keller D, Hernandez LM, et al. Ten Attributes of Health Literate Healthcare Organizations: Institute of Medicine; 2012. https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/BPH_Ten_HLit_Attributes.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brach C. The journey to become a health literate organization: a snapshot of health system improvement. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2017;240:203-237. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/labs/articles/28972519/. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Health Literacy Interventions and Outcomes: An Update of the Literacy and Health Outcomes Systematic Review of the Literature. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Canadian Council on Learning. Health Literacy in Canada: A Healthy Understanding. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; Canadian Council on Learning; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sorensen K, Pelikan JM, Röthlin F, et al. Health literacy in Europe: comparative results of the European Health Literacy Survey (HLS-EU). Eur J Public Health. 2015;25(6):1053-1058. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckv043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nakayama K, Osaka W, Togari T, et al. Comprehensive health literacy in Japan is lower than in Europe: a validated Japanese-language assessment of health literacy. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):505. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1835-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Paasche-Orlow M. Caring for patients with limited health literacy: a 76-year-old man with multiple medical problems. JAMA. 2011;306(10):1122-1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Penaranda E, Diaz M, Noriega O, Shokar N. Evaluation of health literacy among Spanish-speaking primary care patients along the US-Mexico border. South Med J. 2012;105(7):334-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Palumbo R. Examining the impacts of health literacy on healthcare costs. An evidence synthesis. Health Serv Manage Res. 2017;30(4):197-212. doi: 10.1177/0951484817733366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fang MC, Machtinger EL, Wang F, Schillinger D. Health literacy and anticoagulation-related outcomes among patients taking warfarin. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):841-846. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00537.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Heinrich C. Health literacy: the sixth vital sign. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2012;24(4):218-223. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2012.00698.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ishikawa H, Yano E. Patient health literacy and participation in the health-care process. Health Expect. 2008;11(2):113-122. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2008.00497.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Trupin L, Barton J, Evans-Young G, et al. Decisional conflict among vulnerable patient populations with rheumatoid arthritis is associated with limited health literacy and non-English language. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:S1027-S1028. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cifuentes M, Brega AG, Barnard J, Mabachi NM. Implementing the AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit Practical Ideas for Primary Care Practices. Rockville, MD; 2015. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/literacy-toolkit/impguide/healthlit-guide.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kaphingst K, Weaver NL, Wray RJ, Brown MLR, Buskirk T, Kreuter MW. Effects of patient health literacy, patient engagement and a system-level health literacy attribute on patient-reported outcomes: a representative statewide survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):475. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bailey SC, Fang G, Annis IE, O’Conor R, Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolf MS. Health literacy and 30-day hospital readmission after acute myocardial infarction. BMJ Open. 2015;5(6):e006975. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mitchell SE, Sadikova E, Jack BW, Paasche-Orlow MK. Health literacy and 30-day postdischarge hospital utilization. J Health Commun. 2012;17(suppl 3):325-338. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.715233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Griffey RT, Kennedy SK, D’Agostino McGownan L, Goodman M, Kaphingst KA. Is low health literacy associated with increased emergency department utilization and recidivism? Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(10):1109-1115. doi: 10.1111/acem.12476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee J. Flipping the concept of health literacy. http://blog.centerforinnovation.mayo.edu/discussion/flipping-the-concept-of-health-literacy/. Published 2016. Accessed August 2, 2016.

- 20. Baker D. The meaning and the measure of health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):878-883. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Koh HK, Rudd RE. The arc of health literacy. JAMA. 2015;4:1-2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.9978.Conflict. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nutbeam D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(12):2072-2078. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Farmanova E, Bonneville L, Bouchard L. Active offer of health services in French in Ontario: analysis of reorganization and management strategies of healthcare organizations. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2017:1-16. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2446. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kowalski C, Lee S-YD, Schmidt A, et al. The health literate healthcare organization 10 item questionnaire (HLHO-10): development and validation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Johns G. The essential impact of context on organizational behavior. Acad Manag Rev. 2006;31(2):386-408. doi: 10.5465/amr.2006.20208687. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Altin SV, Lorrek K, Stock S. Development and validation of a brief screener to measure the Health Literacy Responsiveness of Primary Care Practices (HLPC). BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16(1):122 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2296/16/122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Koh HK, Brach C, Harris LM, Parchman ML. A proposed “health literate care model” would constitute a systems approach to improving patients’ engagement in care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(2):357-367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Palumbo R, Annarumma C. The importance of being health literate: an organizational health literacy approach. In: Proceedings of the 17th Toulon-Verona Conference ‘Excellence in Services’, Liverpool, England, 28–29 August 2014, Liverpool: Liverpool John Moores University; http://www.toulonveronaconf.eu/papers/index.php/tvc/article/view/161/158. Accessed February 10, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Innis J, Barnsley J, Berta W, Daniel I. Measuring health literate discharge practices. Int J Healthcare Qual Assur. 2017;30(1):67-78. doi: 10.1108/IJHCQA-06-2016-0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Palumbo R. Designing health-literate healthcare organization: a literature review. Heal Serv Manag Res. 2016;29(3):79-87. doi: 10.1177/0951484816639741. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wong BK. Building a health literate workplace. Workplace Health Saf. 2012;60(8):363-369; quiz 370. doi: 10.3928/21650799-20120726-67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Adsul P, Wray R, Gautam K, Jupka K, Weaver N, Wilson K. Becoming a health literate organization: formative research results from healthcare organizations providing care for undeserved communities. Health Serv Manage Res. 2017;30(4):188-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Langley G, Moen RD, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman CL, Provost LP. The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance; Jossey-Bass Publishers; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, et al. Development of methodological guidance, publication standards and training materials for realist and meta-narrative reviews: the RAMESES (Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses – Evolving Standards) project. 2014. September, Southampton: NIHR Journals Library; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK260010/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Weidmer BA, Brach C, Slaughter ME, Hays RD. Development of items to assess patients’ health literacy experiences at hospitals for the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) Hospital Survey. Med Care. 2012;50(9)(suppl 2):S12-S21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wynia MK, Osborn CY. Health literacy and communication quality in healthcare organizations. J Health Commun. 2010;15(suppl 2):102-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ministry of Health. Health Literacy Review: A Guide. Wellington, New Zealand; Ministry of Health; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Module 14: creating quality improvement teams and QI plans. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/prevention-chronic-care/improve/system/pfhandbook/mod14.html. Published 2013. Accessed February 6, 2018.

- 39. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. The Breakthrough Series: IHI’s Collaborative Model for Achieving Breakthrough Improvement. IHI Innovation Series White Paper. Boston: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2003. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/TheBreakthroughSeriesIHIsCollaborativeModelforAchievingBreakthroughImprovement.aspx. Published 2014. Accessed February 10, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nolan TW. Execution of Strategic Improvement Initiatives to Produce System-Level Results. IHI Innovation Series white paper. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. How to improve—science of improvement: forming the team. http://www.ihi.org/knowledge/Pages/HowtoImprove/ScienceofImprovementFormingtheTeam.aspx. Published 2014. Accessed February 6, 2018.

- 42. Health Quality Ontario. Quality improvement primers: quality improvement science. http://www.hqontario.ca/Portals/0/Documents/qi/qi-science-primer-en.pdf. Published 2013. Accessed February 6, 2018.

- 43. Bauer MS, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H, Smith J, Kilbourne AM. An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychol. 2015;3(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s40359-015-0089-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. McLaren L, Hawe P. Ecological perspectives in health research. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(1):6-14. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.018044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Coughlan D, Turner B, Trujillo A. Motivation for a health-literate healthcare system—does socioeconomic status play a substantial role? Implications for an Irish health policymaker. J Health Commun. 2013;18(suppl 1):158-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Andrulis DP, Brach C. Integrating literacy, culture, and language to improve healthcare quality for diverse populations. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31:122-133. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.31.s1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kickbusch IS, Pelikan J, Apfel F, Tsouros AD. Health Literacy: The Solid Facts. Copenhagen, Denmark: www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/190655/e96854.pdf; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Frosch DL, Elwyn G. Don’t blame patients, engage them: transforming health systems to address health literacy. J Health Commun. 2014;19(suppl 2):10-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hood L, Auffray C. Participatory medicine: a driving force for revolutionizing healthcare. Genome Med. 2013;5(12):110. doi: 10.1186/gm514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pelikan J, Dietscher C. [Why should and how can hospitals improve their organizational health literacy?] Warum Sollten Und Wie Konn Krankenhauser Ihre Organ Gesundheitskompetenz Verbessern? Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2015;58(9):989-995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Trezona A, Dodson S, Osborne RH. Development of the organisational health literacy responsiveness (Org-HLR) framework in collaboration with health and social services professionals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):513. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2465-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dietscher C, Pelikan JM. Health-literate hospitals and healthcare organizations—results from an Austrian Feasibility Study on the self-assessment of organizational health literacy in hospitals. In: Health Literacy: Forschungsstand und Perspektiven. Schaffer Doris, Pelikan Jürgen M. (Eds.). Bern, Switzerland: Hogrefe Verlag; 2017:303-314. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hernandez LM. How Can Healthcare Organizations Become More Health Literate? (Workshop Summary). Population Health and Public Health Practice Institute of Medicine; Washington, DC; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kaplan RS. The balanced scorecard for public-sector organizations. Harvard Bus Sch Publ. 1999;1(2):4. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Inamdar N, Kaplan RS, Bower M. Applying the balanced scorecard in healthcare provider organizations. J Healthc Manag. 2002;47(3):179-195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Institute of Medicine & Committee on Quality of Healthcare in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century (vol 323); 2001. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7322.1192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: Translating evidence into action. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001;20(6):64-78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Schillinger D, Keller D. The Other Side of the Coin: Attributes of a Health Literate Healthcare Organization (Commissioned by the Institute of Medicine Roundtable on Health Literacy). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK201219/. Published 2011.

- 59. Rudd RE, Groene RO, Navarro-Rubio MD. On health literacy and health outcomes: background, impact, and future directions. Rev Calid Asist. 2013;28(3):188-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Brega AG, Barnard J, Mabachi NM, et al. AHRQ health literacy universal precautions toolkit, second edition Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 61. French KS. Transforming nursing care through health literacy ACTS. Nurs Clin North Am. 2015;50(1):87-98. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. The Joint Commission. “What Did the Doctor Say ?” Improving Health Literacy to Protect Patient Safety. Oakbrook Terrace, IL; The Joint Commission; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Thomacos N, Zazryn T. Enliven Organisational Health Literacy Self-assessment Resource. Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Enliven; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Jacobson KL, Gazmararian JA, Kripalani S, McMorris KJ, Blake SC, Brach C. Is Our Pharmacy Meeting Patients’ Needs? A Pharmacy Health Literacy Assessment Tool User’s Guide. Rockville, MD; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Deasy N, Fitzgerald M, Kennedy M, McGuane BO, Brien S. Literacy Audit for Healthcare Settings. Dublin, Ireland; https://www.healthpromotion.ie/hp-files/docs/HSE_NALA_Health_Audit.pdf. Published 2009. Accessed February 6, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Dodson S, Good S, Osborne RH. Health Literacy Toolkit for Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Series of Information Sheets to Empower Communities and Strengthen Health Systems. New Delhi, India: World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia; http://www.searo.who.int/entity/healthpromotion/documents/hl_tookit/en/. Published 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. Making health literacy real: the beginnings of my organization’s plan for action. Centers of Disease Control and Prevention; https://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/pdf/planning_template.pdf. Published n.d. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Abrams MA, Kurtz-Rossi S, Riffenburgh A, Savage B. Building health literate organizations: a guidebook to achieving organizational change. http://www.unitypoint.org/filesimages/Literacy/HealthLiteracyGuidebook.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed February 6, 2018.

- 69. DeWalt DA, Broucksou KA, Hawk V, et al. Developing and testing the health literacy universal precautions toolkit. Nurs Outlook. 2011;59:85-94. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Rudd RE, Anderson JE. The Health Literacy Environment of Hospitals and Health Centers. National Center for the Study of Adult Learning and Literacy (NCSALL). Boston, MA; 2006:153. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Peters T. What do you know about literacy in Canada? Literacy Alberta; Calgary, AB; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Clinical Excellence Commission. Health Literacy Guide. Clinical Excellence Commission; Sydney, Australia; n.d. [Google Scholar]

- 73. DeWalt DA, Callahan LF, Hawk VH, et al. Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit (Prepared by North Carolina Network Consor- Tium, the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Under Contract No. HHSA290200710014). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/literacy-toolkit/index.html. Published 2010. Accessed February 6, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Batterham RW, Buchbinder R, Beauchamp A, Dodson S, Elsworth GR, Osborne RH. The OPtimising HEalth LIterAcy (Ophelia) process: study protocol for using health literacy profiling and community engagement to create and implement health reform. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):694. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Groene RO, Rudd R. Results of a feasibility study to assess the health literacy environment: navigation, written, and oral communication in 10 hospitals in Catalonia, Spain. J Commun Healthc. 2011;4(4):227-237. [Google Scholar]