Abstract

Intraosseous ganglion cysts are rare entities, even rarer in the subchondral region of the distal tibia. A 20-year-old male presented to us with complaints of pain and limp in the right ankle joint, which was diagnosed as an intraosseous ganglion cyst of the right distal tibia and was successfully treated with curettage and bone cement with no recurrence seen even after a year.

Keywords: orthopaedics, radiology

Background

A ganglion cyst, also known as a Bible cyst or Bible bump, is a benign soft tissue tumour that is commonly seen and usually occurs near joints, tendons and tendon sheaths, but there are rare occurrences where they have been diagnosed within the bone termed as an intraosseous ganglion cyst (IGC).1 2 IGCs have a peak incidence in the fourth and fifth decades of life with the proximal tibia and carpal bones being commonly affected.3 4 Though there have been some reports in the English literature regarding IGCs around the ankle, most of these lesions reportedly were in the tarsal bones, medial malleolus and some in the lateral malleolus.5 6 IGCs of the distal tibia have rarely been reported.7 8

Case presentation

A 20-year-old male presented to us with a history of pain and limp in the right ankle joint since 1 year, which had deteriorated since 4 months. He had been prescribed analgesics by a local doctor, which did not relieve the pain. There was no history of trauma, fever, loss of weight or any other constitutional symptoms with history and family history being non-contributory. Inspectory findings were normal, while palpation revealed severe tenderness over the anterior aspect of right distal tibia with restricted range of motion (ROM) (dorsiflexion: 100 and plantarflexion: 300) There was no local rise of temperature, and distal neurovascular status was normal.

Investigations

Routine laboratory data were within normal limits.

Radiographs

Anteroposterior and lateral views of the right ankle joint revealed a well-defined, lobulated, solitary lytic lesion with a thin rim of sclerotic bone (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Radiograph of right (anteroposterior and lateral views) ankle showing a well-defined lytic lesion over distal end of tibia just above the articular surface with well-demarcated rim of sclerotic bone.

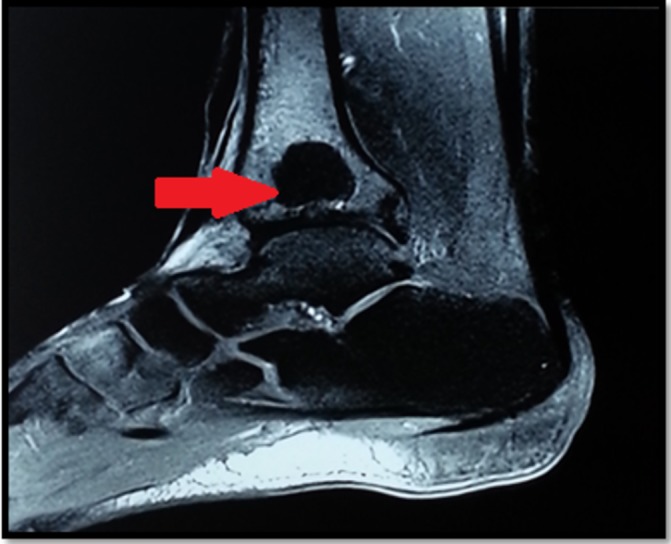

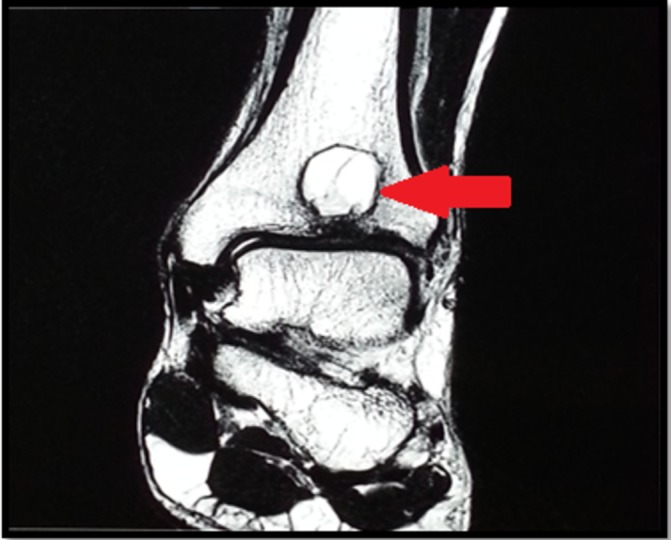

MRI was suggestive of an epiphysial cystic area in the distal tibia in the subchondral region with surrounding minimal marrow oedema (figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

MRI image sagittal GRE view showing a lesion with well-defined and lobulated margin measuring approximately 1.8 cm anterioposteriorly.

Figure 3.

MRI coronal T2 view showing 1.6 cm lesion extending up to the subarticular region with erosion of the subchondral bone.

Differential diagnosis

Aneurysmal bone cyst

geode

Brodie’s abscess.

Treatment

Treatment plan: (A) excision of cyst with curettage and filling of the defect with bone cement and (B) to send the excised cyst for histopathological examination.

Operative procedure

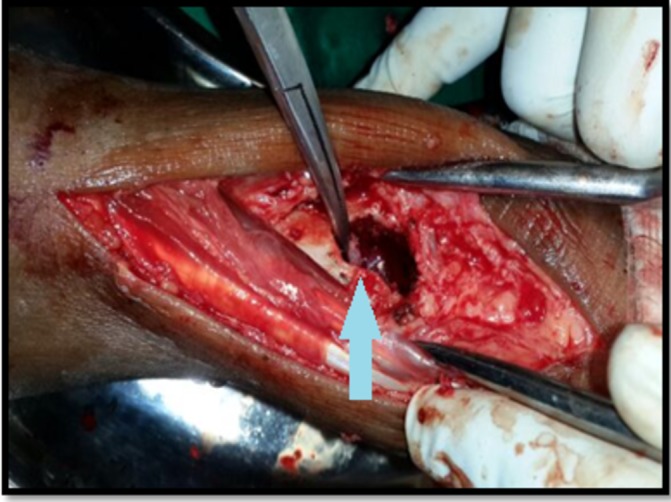

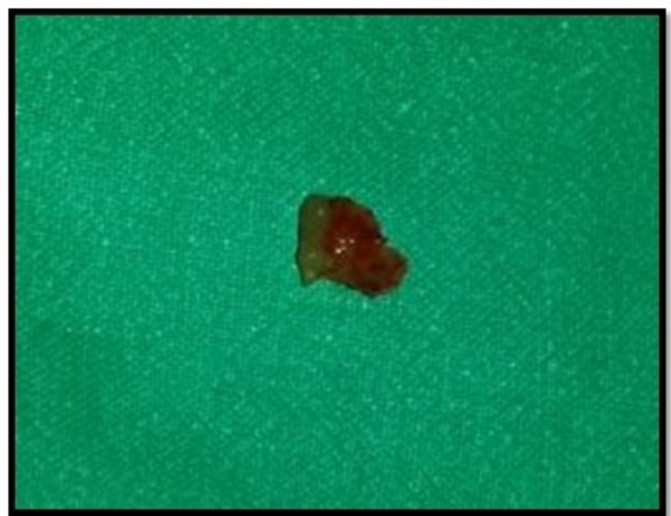

After spinal anaesthesia was given, an anterior incision was taken over lower end of tibia under C arm vision. Soft tissue was dissected, bone was exposed and a cortical window of approximately 3 cm × 2 cm was made (figure 4). The cyst was exposed and was gelatinous in consistency measuring approximately 1.5 cm × 1.5 cm (figure 5). Curettage was done, and a thorough wash was given. Defect was filled with 20 gm of bone cement(figure 6). After a repeat thorough wash, wound closure was done, and a below knee posterior slab was given. The intraoperative specimen (cyst) was sent for histopathological evaluation. Postoperative radiograph was done (figure 7). Histopathology confirmed the diagnosis of IGC.

Figure 4.

Cortical window being made (arrow).

Figure 5.

Cyst excised of approximately 1.5 cm × 1.5 cm.

Figure 6.

Cavity packed with bone cement (arrow).

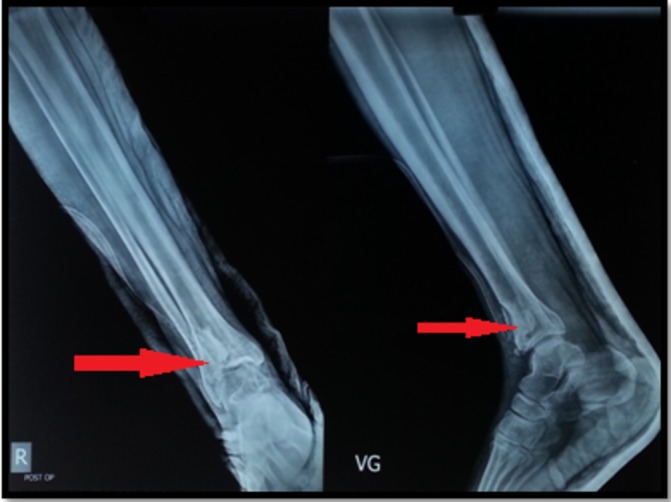

Figure 7.

Postopoperative radiograph (anteroposterior and lateral) showing the incorporation of bone cement at the defect.

Postoperatively sterile dressing was done on postoperative days (PODs) 2 and 8, and the ankle ROM was started on POD 8. Wound was healthy, and sutures were removed on POD 12. Non-weight-bearing walking was started with a walker, and the patient was discharged.

Outcome and follow-up

Patient was followed up monthly, and full weight-bearing walking was started after 2 months. One year has passed since the surgery, and the patient shows no signs of recurrence and is completely relieved of pain and limping.

Discussion

Though subchondral cyst/geodes and IGCs are subtypes of intraosseous cysts, they differ from each other and are separate entities. A subchondral cyst is an intraosseous cyst that occurs beneath an articular surface of a bone and is produced in areas of damaged articular cartilage, subjacent to the underlying subarticular cortical plate. Subchondral cysts are of variable size from a few millimetres to over a centimetre, and a large subchondral cyst may be referred to as a geode, whereas an IGC is a benign cystic lesion made up of fibrous tissue with extensive mucoid changes located in the subchondral bone adjacent to a joint.9 10 An IGC is considered to be a lesion that is distinct from a subchondral cyst; subchondral cysts often communicate with the joint cavity through the articular surface and therefore are filled with synovial fluid, while IGCs rarely communicate with the joint cavity and are filled with viscous mucoid material.10 11 Subchondral cysts have been ‘traditionally’ taught to be one of the four cardinal radiological features of osteoarthritis and are invariably found in rheumatoid arthritis too, but association of IGC to osteoarthritis is rarely seen.12 13 In the present case, neither did the IGC communicate with the ankle joint nor was it associated with osteoarthritis, which is similar to the studies published by Feldman et al and Sakamoto et al.9 13 There seems to be two fundamental types of IGC: one originating by penetration of an extraosseous ganglion into the underlying bone, and the other being idiopathic.12 The IGC reported in our case is of idiopathic type since no penetration of an extraosseous ganglion into the distal tibia was found. Idiopathic type of IGC originates from modified mesenchymal or synovial cells at the capsule–synovial interface in response to repeated minor injury, explaining high prevalence of IGCs in the scapholunate site where the motion and force is concentrated. Repetitive minor trauma and mechanical stress cause intramedullary vascular disturbance, and consequently, aseptic bone necrosis leading to proliferation of fibroblasts and histiocytes and production of hyaluronic acid with mucoid degeneration during tissue revitalisation occur to form a cyst.14 In our case, the IGC was located in the subchondral region of the distal tibia where repetitive mechanical stress occurs. Since our patient was a labourer, we speculated that repetitive microtrauma might have been the cause of the IGC. A thorough search of literature revealed that there have been three articles of IGCs of the distal tibia reported to date, with a total of 23 cases.9 13 15 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case to be reported from the Indian subcontinent.

Learning points.

Intraosseous ganglion cysts of the distal tibia are rare.

For the confirmation of diagnosis, surgical excision has to be performed.

Curettage with filling of the defect with bone cement is the mode of treatment.

Intraosseous ganglion cysts should be considered in the differentials of benign osteolytic lesions of the ankle joint.

Footnotes

Contributors: PC: diagnosis and patient management. AM and PC: diagnosis, literature search and preparing the manuscript. VP and MP: patient management.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. McDonald RE, Mullens DJ. Ganglion cyst treatment using the ganglion suture technique. Osteopathic Family Physician 2013;5:123–7. 10.1016/j.osfp.2013.01.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fealy MJ, Lineaweaver W. Intraosseous ganglion cyst of the scaphoid. Ann Plast Surg 1995;34:215–7. 10.1097/00000637-199502000-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Williams HJ, Davies AM, Allen G, et al. Imaging features of intraosseous ganglia: a report of 45 cases. Eur Radiol 2004;14:1761–9. 10.1007/s00330-004-2371-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Daly PJ, Sim FH, Beabout JW, et al. Intraosseous ganglion cysts. Orthopedics 1988;11:1715–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Büchler L, Hosalkar H, Weber M. Arthroscopically assisted removal of intraosseous ganglion cysts of the distal tibia. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009;467:2925–31. 10.1007/s11999-009-0771-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Uriburu IJ, Levy VD. Intraosseous ganglia of the scaphoid and lunate bones: report of 15 cases in 13 patients. J Hand Surg Am 1999;24:508–15. 10.1053/jhsu.1999.0508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ferkel RD, Field J, Scherer WP, et al. Intraosseous ganglion cysts of the ankle: a report of three cases with long-term follow-up. Foot Ankle Int 1999;20:384–8. 10.1177/107110079902000608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Murff R, Ashry HR. Intraosseous ganglia of the foot. J Foot Ankle Surg 1994;33:396–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Feldman F, Johnston A. Intraosseous ganglion. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 1973;118:328–43. 10.2214/ajr.118.2.328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Helwig U, Lang S, Baczynski M, et al. The intraosseous ganglion. A clinical-pathological report on 42 cases. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1994;114:14–17. 10.1007/BF00454729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Landells JW. The bone cysts of osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1953;35-B:643–9. 10.1302/0301-620X.35B4.643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Calcagnotto G, Sokolow C, Saffar P. Les kystes synoviaux intra-osseux du semi-lunaire : problèmes diagnostiques. Chir Main 2004;23:17–23. 10.1016/j.main.2003.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sakamoto A, Oda Y, Iwamoto Y. Intraosseous Ganglia: a series of 17 treated cases. Biomed Res Int 2013;2013:1–4. 10.1155/2013/462730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Seymour N. Intraosseous ganglia of medial malleolus. JBJS 1968;50:134–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schajowicz F, Clavel Sainz M, Slullitel JA. Juxta-articular bone cysts (intra-osseous ganglia): a clinicopathological study of eighty-eight cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1979;61:107–16. 10.1302/0301-620X.61B1.422629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]