Abstract

The development processes of arteries and veins are fundamentally different, leading to distinct differences in anatomy, structure, and function as well as molecular profiles. Understanding the complex interaction between genetic and epigenetic pathways, as well as extracellular and biomechanical signals that orchestrate arterial venous differentiation, is not only critical for the understanding of vascular diseases of arteries and veins but also valuable for vascular tissue engineering strategies. Recent research has suggested that certain transcriptional factors not only control arterial venous differentiation during development but also play a critical role in adult vessel function and disease processes. This review summarizes the signaling pathways and critical transcription factors that are important for arterial versus venous specification. We focus on those signals that have a direct relation to the structure and function of arteries and veins, and have implications for vascular disease processes and tissue engineering applications.

Keywords: arterial venous endothelial cells, vascular bioengineering, stem cell differentiation, vascular development

1. INTRODUCTION

Arteries and veins play different roles in human physiology. Typically, arteries carry blood flow away from the heart while veins return the blood toward the heart. This is true regardless of the oxygen level: Consider the pulmonary or umbilical artery and vein. Arteries adapt to high blood pressure and flow from the heart with thick layers of tunica media and adventitia, as well as abundant smooth muscle cells (SMCs) that produce elastic extracellular matrix (ECM) and regulate vascular tone. Veins, by contrast, have much thinner vessel walls but a larger diameter to accommodate greater blood volume so as to minimize resistance to flow. The regulation of vascular tone is an arterial function that occurs primarily at the level of the arterioles, whereas postcapillary venules are the primary sites of leukocyte extravasation during inflammation (Figure 1). In addition to their anatomical, structural, and functional differences, arteries and veins differ molecularly by expressing different molecular profiles. The molecular differences between arteries and veins not only exist in the major blood vessels but extend down to the capillary level, suggesting that arterial and venous cells have different developmental origins.

Figure 1.

Formation of arteries and veins. During early development, vascular progenitors, also known as angioblasts, that are differentiated from mesoderm start to acquire either arterial or venous fate, and they assemble into a primary network called the vascular plexus. The vascular plexus subsequently undergoes extensive remodeling through EphrinB2/EphB4-mediated cell repulsion into arterial and venous territories.

Meanwhile, nerve-derived signals align the blood vessels and cause arterial differentiation. When the heart starts to beat, the arterial blood vessels are exposed to higher blood pressure and flow, which further drive arterial differentiation and mature phenotype maintenance. Abbreviations: COUP-TF11, chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor 2; Cx40: connexin 40; Dll4, delta-like ligand 4; Nrp2, Neuropilin-2; Sox17, sex-determining region Y box 17; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Previously, it was thought that arterial and venous endothelial cells (ECs) share the same characteristics in the early stages of development, and that their mature phenotype is completely determined by different hemodynamic conditions at the later stages of development. However, recent studies have demonstrated that arterial versus venous identity is genetically predestined before the onset of flow, as evidenced by the appearance of several arterial venous molecular markers such as EphrinB2 and EphB4 even before the heart starts to beat (1–3). Several other early markers were also identified. For example, preflow segregation of Neuropilin-1 (Nrp1) and Neuropilin-2 (Nrp2) to the arterial and venous plexus regions, respectively, was observed in chick embryos before EphrinB2 appeared (4). During early stages of embryonic development, EC progenitors (angioblasts) differentiate from mesoderm and form a fragile and irregular tubular network, called a primitive vascular plexus. The vascular plexus then undergoes intense remodeling, which involves segregation of arterial and venous progenitors into their respective zones (Figure 1).

Lineage-tracing experiments in both mice and zebrafish suggest that a subset of arterial- and venous-fated cells may initially occupy the primitive vasculature and subsequently separate from one another to form distinct dorsal aortas and cardinal veins, and that angioblasts can become only arterial or venous cells but not both (5–8). More recent studies have suggested that arterial and venous ECs are derived from different pools of angioblasts that arise at distinct locations (9). The segregation of arterial and venous progenitors from a mixed, heterogeneous cell population is an important process for the establishment of arteries and veins later on, and is mediated by cell surface receptor–ligand interactions. One such interaction is EphrinB2/EphB4-mediated cell–cell repulsion, which separates EphrinB2-expressing arterial cells from EphB4-expressing venous cells (Figure 1). This interaction is critical for establishing the demarcation of arterial and venous territories (7). In the zebrafish embryo, angioblasts initially form a single precursor vessel that expresses both EphrinB2 and EphB4. Ventral migration of EphB4+ ECs leads to the separation of the dorsal aorta from the cardinal vein by repulsion from EphrinB2+ cells (7). In mice, the cardinal vein forms by sprouting of EphB4+ ECs from an early dorsal aorta that contains angioblasts expressing EphrinB2+, EphB4+, and uncommitted precursor cells (6).

Vascular segregation is a complex process that is determined mostly by genetic/epigenetic programs and occurs in the absence of blood flow. However, when the heart starts to beat, arteries are exposed to higher pressure and flow shear stress, which further remodel their functional phenotypes. The greater plasticity of ECs at this stage of development enables phenotypic switching from venous to arterial EC identity in order to accommodate a changing hemodynamic environment (10). Furthermore, under flow conditions, arterial ECs elicit signals to recruit SMCs and pericytes, which in turn contribute mechanical properties of the arterial wall, enabling it to withstand high vascular pressures. We now know that EC specialization depends upon genetic/epigenetic programs, but also that environmental factors such as growth factors, ECM, and biomechanical forces are indispensable for remodeling and maintaining EC identity later on. Next, we review the signaling pathways and critical transcriptional programs that determine EC fate during vascular development.

2. GENETIC/EPIGENETIC PROGRAMS AND SIGNALING PATHWAYS THAT CONTROL ARTERIAL VENOUS SPECIFICATION DURING DEVELOPMENT

EC progenitors can be detected in early embryonic development. They express several general endothelial-specific markers such as vascular endothelial cadherin (VE-cadherin), platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM, or CD31), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor 2 (VEGFR2 or Flk1). Vascular development involves complex interactions of gene expression, both spatially and temporally. Endothelial differentiation is orchestrated by a large set of transcription factors, including the ETS (ETS domain–binding factor), GATA (GATA-binding factor), KLF (Krüppel-like factor), HOX (Homeobox), SOX (sex-determining region Y box), and FOX (Forkhead box) families of transcription factors (11–14).

Later in development, EC acquire either arterial or venous identity. The specification of arterial and venous identities and the formation of a hierarchical tree with specific inflow/outflow compartments are the essence of a functional vascular network. To date, many signaling pathways have been identified that play a role in arterial specification (Figure 2), among which Notch pathway activation is essential (15–21). Inhibition of the Notch pathway inevitably disrupts arterial differentiation, which leads to a malformed vascular network and is usually embryonic lethal. Notch signaling involves cell surface receptor–ligand interactions. In vertebrates, there are four heterodimeric, transmembrane receptors (Notch1–4) and five ligands (Jagged1, Jagged2, Dll1, Dll3, and Dll4). Upon Notch ligand binding, Notch receptor undergoes cleavage and Notch intracellular domain (NICD) goes into the nucleus and actives downstream arterial-specific genes such as Hes1, Hes2, Hey1, and Hey2 (5, 22), which in turn upregulate the arterial marker EphrinB2. Because most Notch ligands are also transmembrane proteins, the receptors are normally triggered only by direct contact with neighboring cells. Intriguingly, both Notch receptors (e.g., Notch4) and ligands (Jag1, Jag2, Dll4) are restricted to arterial vessels (23). These molecules need to be expressed before cells can engage Notch signaling, and it is still unknown how these molecules are upregulated in arterial-specific ECs even before Notch activation occurs.

Figure 2.

The key transcriptional programs and signaling pathways in determining arterial and venous identities. Abbreviations: BRG1, Brahma-related gene 1; COUP-TFII, chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor 2; Cx40, connexin 40; Dll4, delta-like ligand 4; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; NICD, Notch intracellular domain; Nrp1, Neuropilin-1; Nrp2, Neuropilin-2; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; RBPJ, recombining binding protein suppressor of hairless; Sox17, sex-determining region Y box 17; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; VEGFR2, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2.

Several signaling pathways are implicated in Notch activation. Investigators working in zebrafish vascular development proposed a model of Shh (Sonic hedgehog) → VEGF → Notch to determine arterial cell fate (24). Shh is a member of the hedgehog family and plays a general role in embryonic development. In zebrafish, Shh is secreted by the notochord at the midline of the developing embryo, and the resulting gradient of Shh induces the arterial fate of nearby EC progenitors. Shh acts as a secreted molecule and binds to the transmembrane receptor Patched (Ptc) and the G protein–coupled receptor Smoothened (Smo). Upon binding, Shh acts indirectly by inducing VEGF production in adjacent somites, and subsequently activates Notch signaling to promote arterial specification (17, 25–27). In zebrafish, Shh signaling clearly plays an important role in arterial specification. However, whether this is the case in mice and humans is still unknown. For example, in Shh-deficient mice, early vascular development that is mediated by VEGF/VEGFR2 signaling proceeds normally (28). Therefore, it is possible that murine Shh signaling is not critical for arterial venous specification.

VEGF plays an essential role in vascular development, as the deletion of the VEGF gene completely abolishes vasculature formation (29). Therefore, VEGF is important for endothelial specification in general. However, whether it is specific for arterial or venous differentiation is debatable. Investigators have speculated that early arterial and venous cells are determined by a gradient of VEGF signals, in which high VEGF concentration leads to arterial ECs while low VEGF concentration gives rise to venous ECs (30). However, this hypothesis is not entirely convincing, because graded signaling by VEGF can affect downstream expression of both the arterial marker EphrinB2 and the venous marker EphB4. Recent studies using embryonic stem cells also showed that VEGF treatment slightly upregulates EphrinB2 expression, but has very little effect on the venous markers COUP-TFII (chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor 2) and EphB4 (30). On the basis of these facts, it is difficult to conclude that VEGF concentration alone is sufficient to distinguish between arterial and venous cell fate.

Regardless of its role in arterial venous specification, VEGF stimulation activates pathways including the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway and the extracellular signal–regulated kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase (ERK/MAPK) pathways. Several studies have demonstrated antagonistic cross talk between the PI3K and ERK/MAPK pathways: Strong stimulation of the ERK pathway directs EC differentiation to an arterial phenotype, whereas activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway inhibits arterial specification in favor of venous differentiation (31–34). Furthermore, a constitutively active form of ERK increased the expression of all arterial markers, even in the absence of VEGF stimulation. Recent research has provided some insight into how the MAPK pathway may regulate arterial fate: An arterial-specific enhancer in the Dll4 gene is positively regulated by MAPK activity, whereas it is negatively regulated by PI3K (35). Importantly, MAPK signaling promotes the binding of ETS factors to both Dll4 and Notch4 enhancer, suggesting that MAPK/ERK and ETS factors may act upstream of Notch signaling. Because both MAPK and PI3K pathways are activated downstream of the VEGF receptor, exactly why MAPK signaling (as opposed to the PI3K pathway) is preferentially activated in arterial cells remains an intriguing question. It is possible that the same ligand (VEGF) and receptor (VEGFR2) may induce two different differentiation pathways, depending on the intensity of the activation signal, or perhaps coexistent activation of other, independent signaling pathways.

Other models of arterial differentiation suggest alternative pathways that may distinguish VEGF signaling between arterial and venous ECs. During early vascular development, the associated nerve develops before the onset of arterial specification and cells close to the nerve develop into arteries, whereas those far away from the nerve develop into veins (36, 37). Subsequent studies have demonstrated that nerve-derived VEGF is critical for arterial specification (Figure 1). EC progenitors close to the nerve express Nrp1, whereas cells far away lack Nrp1 expression. Because Nrp1 is a coreceptor for VEGFR2, it enhances VEGF signals in Nrp1+ cells, while VEGF signal is weaker in Nrp1− cells. In addition, VEGF stimulation upregulates Nrp1 expression. This VEGF/Nrp1-mediated positive feedback loop is believed to contribute to arterial formation close to nerves (36, 37).

As coreceptors, Nrp1 and VEGFR2 cluster upon VEGF binding. Use of mutations of the Nrp1 cytoplasmic tail showed that the cytoplasmic tail of Nrp1 mediates the interaction between Nrp1/VEGFR2 and synectin, leading to delayed trafficking of endocytosed VEGFR2. This, in turn, leads to dephosphorylation of VEGFR2 at tyrosine Y1175, a residue that is involved in activating ERK signaling (38). These findings establish Nrp1 as a specific regulator of VEGF-induced VEGFR2 trafficking and ERK signaling that is critical for arterial specification. Consistent with these findings, Nrp1 is expressed in arterial ECs specifically (36, 39, 40). Nrp1-mutant mouse embryos show impaired arterial differentiation, which is independent of blood flow patterns (41).

In addition to intracellular signaling pathways, several core transcriptional programs play critical roles in determining arterial venous cell fate. One of them is the SoxF family of transcription factors. SoxF plays multiple roles in many tissues and organs during development, and among them Sox7, Sox17, and Sox18 have been implicated in arterial venous specification (42–44). In particular, Sox17 is selectively activated in arteries but not in veins (45). Sox17, together with immunoglobulin κ J region (RBPJ) and NICD, binds to the enhancer region of the Dll4 gene, directly upregulating arterial-specific Dll4 expression (45). These findings suggest that Sox17 acts directly upstream of Notch receptor expression during the acquisition of arterial identity (46). In the absence of Sox17, ECs lose arterial markers and are unable to recruit pericytes and SMCs to form the correct arterial wall structure (47), suggesting that Sox17 is indispensable for acquisition and maintenance of arterial function. The importance of Sox17 in human vascular diseases has also been validated. A multistage, genome-wide association study of several thousand patients with intracranial aneurysms identified a susceptibility locus that contains the Sox17 gene (48–50), suggesting that Sox17 may involve EC–SMC interaction, SMC recruitment to cerebral arteries, or ECM remodeling.

Compared with arteries, little is known about how veins are formed. Recent studies in mice have unexpectedly revealed an arterial origin of venous endothelium. The dorsal aorta contains a small population of ECs that express the venous markers COUP-TFII and EphB4. These cells migrate from the dorsal aorta into the cardinal vein by EphrinB2/EphB4-mediated repulsion. This population of cells then undergoes further remodeling to become venous endothelium (6). Previously, it was thought that the venous cell fate is the default pathway if Notch is not activated. However, this concept was challenged after the venous-specific transcription factor COUP-TFII was discovered (43). Studies have shown that venous identity is acquired not from a lack of Notch signaling but rather by active involvement of COUP-TFII. In the absence of COUP-TFII, arterial markers appear ectopically in the venous circulation. Meanwhile, COUP-TFII also inhibits Notch signaling by directly suppressing the expression of Nrp1 and Foxc1, two upstream regulators of Notch signaling (51). Despite its important role for venous specification, how COUP-TFII is induced by external stimuli remains elusive because most growth factors, ECM constituents, and biomechanical forces have very little influence on COUP-TFII expression. However, recent research has provided some new insights into COUP-TFII regulation. For example, angiopoietin-1/Tie2 is involved in COUP-TFII regulation via PI3K/Akt-mediated stabilization of COUP-TFII (52, 53). Another study showed that COUP-TFII may be epigenetically modified to allow gene activation for venous fate specification. The mammalian SWITCH/sucrose nonfermentable (SWI/SNF)-like brahma-related gene 1 (BRG1, also known as Smarca4), encoding a chromatin-remodeling enzyme, positively regulates COUP-TFII expression, and its inactivation results in the induction of arterial markers in veins. Mechanistically, Brg1 binds the promoter 1.2 kb upstream region of the COUP-TFII gene. Brg1 depletion results in a reduced H3K9ac (histone H3 lysine 9 acetylation) active enhancer mark and increases histone H3 binding at both Brg1 binding sites, leading to decreased RNA polymerase II recruitment at the COUP-TFII promoter region and reducing COUP-TFII gene expression (54).

3. NERVE-DERIVED SIGNALS AND BIOMECHANICAL FORCES IN THE REGULATION OF ARTERIAL VENOUS IDENTITY

Blood vessels and nerves often run alongside one another, raising the interesting possibility that the mechanisms involved in wiring neural and vascular networks may share some similarities. In fact, numerous facts suggest that axon guidance molecules are also involved in blood vessel branching patterns. Examples of such signals include the Netrins and their Unc5 receptors, Semaphorins and their Neuropilin and Plexin receptors, Slits and their Robo receptors, and the Ephrins and their Eph receptors (55, 56).

Emerging evidence shows that blood vessels, which develop later than nerves, follow signals from the nervous system (Figure 1). Nerve effects dictate both arterial location and alignment, as well as specification. These two facets involve two different molecular mechanisms. First, peripheral nerve–derived Cxcl12 regulates the alignment of arterial vessels along the branching nerve, by guiding EC migration via Cxcr4 receptor on ECs (57). Second, nerve-derived VEGF promotes arterial differentiation via Nrp1-mediated positive feedback, as described above (37). These findings suggest a coordinated sequential action, in which nerve-derived Cxcl12 recruits and aligns vessels along nerves while subsequent arterial differentiation requires local action of nerve-derived VEGF in the aligned vessels.

Sympathetic innervation is another important feature of arteries. Innervation of arteries allows released neurotransmitters to act upon SMCs, and thereby provide control of vascular tone in response to physiological needs. Furthermore, sympathetic innervation promotes arterial EC fate in vivo via the sympathetic neurotransmitter norepinephrine. Mechanistically, sympathetic nerves increase ERK activity via stimulation of adrenergic α1 and α2 receptors from norepinephrine (58). Taken together, these findings extend our understanding of the sympathetic nervous system and its impact on arterial venous EC plasticity, and provide insights into the maintenance of endothelial identity in the adult.

Following early arterial venous specification, described above, environmental factors such as shear stress and transmural pressure are indispensable for the control and maintenance of cell identity later on, suggesting that earlier vascular progenitors have a degree of plasticity (59). For example, in chick embryos, ligation of the extraembryonic artery induces a profound vascular remodeling and morphological and genetic transformation of arteries into veins, and vice versa (60). Genetic perturbation of embryonic heart contraction in mice recently revealed that blood flow is a critical regulator of arterial venous remodeling in the embryo and yolk sac, since loss of cardiac-derived flow can significantly alter vessel morphogenesis and arterial venous gene expression (61, 62). However, arterial venous plasticity is time sensitive during embryonic development (40). For example, arterial and venous vessel grafts from quail embryos integrate successfully into both chick arteries and veins until embryonic day 7. However, after day 11, that plasticity is lost, and cell colonization of host vessels is restricted on the basis of their original identity (40). Taken together, these findings suggest that embryonic ECs exhibit a significant degree of plasticity with respect to arterial venous differentiation that is lost later in development.

This loss of plasticity is even more obvious in vein grafts, which are subjected to arterial hemodynamics after bypass surgical procedures. Bypass procedures are often performed in elderly patients, when it is expected that the plasticity of ECs is mostly lost. Experiments on vein graft adaptation in aged animals showed that the venous marker EphB4 is lost in vein grafts, but that arterial markers EphrinB2, Dll4, and Notch4 are not induced; these findings suggest that the vein graft does not completely adapt to the arterial circulation (63). Further studies in rodent models showed that EphB4 is an active mediator of vein graft remodeling, which is mediated through endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) (64, 65). But in all of these experimental scenarios, the venous graft did not adopt arterial identity. Other studies have also confirmed that adult ECs demonstrate very limited upregulation of arterial markers in response to arterial-like flow conditions (66). Furthermore, vein graft failure contributes significantly to morbidity and mortality of patients who have undergone bypass surgery. By contrast, bypass grafting performed using the internal mammary artery has much better clinical outcomes, implying that arterial identity is important for long-term function of arterial conduits. Further studies on vein graft adaptation are warranted to improve the long-term patency of vein grafts.

4. MOLECULAR PROFILE OF ADULT BLOOD VESSEL IDENTITY AND ROLES IN VASCULAR FUNCTION AND DISEASE PROCESSES

The differential expression of molecular markers in arteries and veins suggests that these markers may also influence disease processes of blood vessels. Indeed, some of the earliest-identified arterial venous markers have been implicated in vascular function and disease. For example, arterial ECs have higher expression of EphrinB2 than do venous ECs. Recent studies discovered new functions of EphrinB2 in arteries, indicating that it is required for EC-dependent arterial vasodilation in response to flow or to acetylcholine. For example, a subset of EphrinB2 proteins colocalize with caveolin-1 to regulates eNOS and nitric oxide signaling in adult endothelium (67). Additionally, EphrinB2 located on the luminal surface of arterial ECs physically interacts with monocyte EphB receptors and induces proinflammatory activation of monocytes, which may contribute to the pathogenesis of arteriosclerosis (68). Similarly, Notch ligands and receptors such as Dll1, Dll4, Notch1, and Notch4 may signal SMCs and macrophages during inflammatory processes in ways that are different from venous ECs. Increased expression of Notch1, Notch4, and Hey1 was observed at atherosclerotic sites of both human and mouse aortas (69), and attenuation of Notch1 signaling by Notch1 inhibition with the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT suppressed intimal hyperplasia (70–73).

By contrast, the venous transcription factor COUP-TFII regulates not only arterial venous fate but also some pathophysiological functions of adult blood vessels. Suppression of COUP-TFII in venous ECs switched the cells’ identity to arterial ECs through upregulation of many arterial markers, as well as many proatherogenic and osteogenic genes. The differential expression of proatherogenic and osteogenic genes was also confirmed in arterial and venous ECs’ gene profiles in vivo. Conversely, overexpression of COUP-TFII suppresses the proatherogenic and osteogenic genes. These data suggest that COUP-TFII functions as the suppressor of the proatherogenic and osteogenic potential in veins, and thus may play an important role in the different susceptibilities of arteries and veins to vascular diseases such as atherosclerosis and vascular calcification (66).

Most arterial venous differentiation studies have been conducted in developing zebrafish or in mice embryos during early stages of development. Because arterial venous identity is acquired in a stepwise fashion, different arterial venous markers appear and disappear at various time points throughout development (74); thus, the results of such early-stage animal studies are highly dependent on the timing of the study. In addition, there are obvious significant differences between zebrafish, mouse, and human blood vessel development, so the results from zebrafish may not extrapolate to other species. Therefore, direct examination of the genetic profiles of adult vessels versus developing embryos can shed additional light on adult-onset cardiovascular disease. Toward this end, some studies have utilized cultured human umbilical arterial versus venous ECs, or cultured human coronary ECs versus saphenous vein ECs (75). Studies have found that in vitro cultured ECs lose significant transcriptional information and converge into a similar phenotype within a few days, probably because two-dimensional culture plastic is dramatically different from the in vivo environment. Therefore, data from cultured ECs do not accurately represent arterial venous gene expression profiles in vivo. However, the “missing” gene expression profiles can be restored by the effects of eight core transcription factors: Prdm16, Msx1, Emx2, Nkx2–3, TOX2, Hey2, Sox17, and Aff3. Combined expression of these transcription factors in cultured human umbilical vein ECs restored their arterial EC fingerprint and phenotype in culture (76).

A comprehensive study of the molecular signatures of endothelium in adult artery versus vein requires that endothelial messenger RNA (mRNA) be isolated from aorta and vena cava without SMC contamination. Genome-wide transcriptional analyses have demonstrated a dramatic differential expression profile in arterial versus venous ECs in the mouse (66). Surprisingly, some of the early arterial markers, such as Hey1, Hey2, Jag1, Jag2, Nrp1, Notch1, Dll1, and Cxcr4, are the same in adult arterial and venous ECs. These genes may be involved in early arterial venous specification but may not be differentially regulated during the maintenance of adult phenotypes. This study also confirmed the continued expression in the adult of some known arterial markers, such as Cx37, Cx40, EphrinB2, Notch4, Dll4, and Sox17, as well as some venous markers, such as Nrp2, COUP-TFII, and EphB4. Because these markers can identify artery or vein throughout development and into adulthood, they are more robust markers than those that disappear in the adult vessel. Interestingly, we found that arterial ECs have higher expression of prothrombotic genes, including PAI1 (plasminogen activator inhibitor 1), VCAM1, ACE (angiotensin-converting enzyme), BMP4 (bone morphogenetic protein 4), PDGFB, and THBS1 (thrombospondin 1). By contrast, venous ECs have higher expression of antithrombotic genes such as tPA (tissue plasminogen activator), uPA (urokinase plasminogen activator), and TFPI2 (tissue factor pathway inhibitor 2) (Figure 3). This finding is consistent with another study showing that venous ECs are less thrombogenic than arterial ECs (77).

Figure 3.

Arterial and venous endothelial cells have different gene expression profiles related to the functional status of the endothelium. Endothelial messenger RNA was isolated from mouse aorta and vena cava and subjected to transcriptional profiling analysis. Modified from Reference 66.

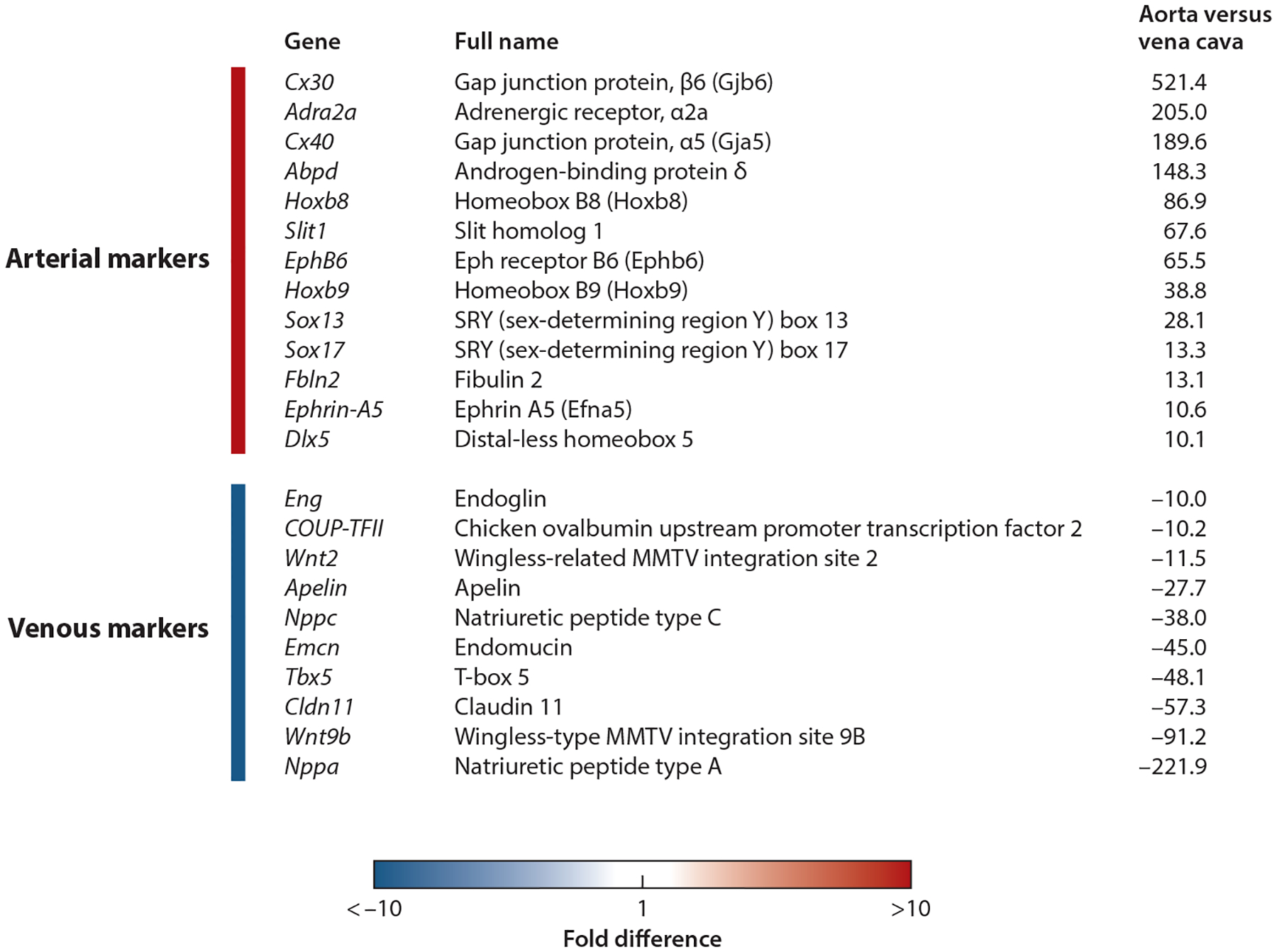

The same study identified additional, stronger arterial venous markers in the mouse. Importantly, some of the differentially expressed genes between artery and vein in the adult differed in expression by several hundred–fold (Figure 4). Those that can be used as arterial markers of the adult endothelium include Cx30, Cx40, Hoxb8, Hoxb9, Slit1, EphB6, Sox13, Sox17, and EphrinA5. Interestingly, arterial ECs also express some genes that are closely associated with arterial functions, such as ABP (androgen-binding protein), which is related to cardiovascular hormone; Adr (adrenergic receptor), which is involved in sympathetic signaling of arteries; and Fbln (fibulin), which is involved in elastin fiber assembly. Arterial ECs also express very high levels of Dlx5, which is involved in bone development.

Figure 4.

Selected highly differentially expressed genes in aorta versus vena cava endothelial cells. Modified from Reference 66.

By contrast, adult venous ECs express a completely different set of markers, including Wnt2, Wnt9b, Tbx5, and COUP-TFII. Venous ECs have markedly strong expression of several cardiovascular protectant factors, such as natriuretic peptides A and C (ANP, CNP), which are potent vasodilators; apelin, which regulates fluid homeostasis; and endomucin, which prevents contact between leukocytes and adhesion molecules in noninflamed endothelium (78).

5. DIFFERENTIATION OF PLURIPOTENT STEM CELLS TOWARD ARTERIAL AND VENOUS LINEAGES

As discussed above, arterial and venous ECs have unique molecular profiles that maintain their specific physiological functions in their native environments. Compared with arterial ECs, venous ECs have higher antithrombotic and lower proinflammatory and osteogenic properties, which may protect venous ECs from vascular diseases such as atherosclerosis and vascular calcification. These differences may also explain why such vascular diseases often occur in arteries but never in native veins, given the same systemic cardiovascular risk factors. Thus, venous ECs may be less prone to disease than arterial ECs, at least when they are resident in their native venous environment. However, when veins are taken out of their native environment and exposed to arterial hemodynamic stimuli, the venous transcriptional programs and their concomitant protection are lost. Partly as a result, vein grafts have worse clinical outcomes than do arterial grafts. Therefore, it remains unclear which ECs are the better choice for tissue-engineered vascular grafts. Inducing arterial or venous EC specification in engineered vasculature will likely have diverging impacts on long-term function in vivo.

With the development of the induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC), it is now possible to derive patient-specific vascular ECs from very primitive stem cells. Such iPSC-derived ECs can be used in a variety of therapies, such as tissue-engineered vascular grafts and revascularization of ischemic tissues, and will likely cause no immune reaction if the cells are derived from autologous sources. To date, various methods have been developed to differentiate pluripotent stem cells into general vascular ECs (79, 80), but reports of arterial or venous specification are limited.

Because arterial flow plays an important role in the continuous remodeling of arteries during development, it is anticipated that applying fluid shear stress to stem cell–derived EC progenitors will enrich their arterial marker expression. This idea has been confirmed by several studies showing that arterial shear stress upregulates several arterial markers in stem cell–derived EC precursors (81, 82). Use of a biomimetic flow bioreactor allowed human iPSC–derived ECs to differentiate into a mature phenotype and express eNOS, a unique feature of vascular ECs. Under arterial shear stress, arterial markers EphrinB2, Cxcr4, Cx40, and Notch1 were also increased (83). Another study found that adding 8-bromo-cAMP (8-bromoadenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate) or adrenomedullin, an endogenous ligand-activating cAMP, enhanced the induction of arterial ECs. Stimulation of the cAMP pathway activates Notch and glycogen synthase kinase 3β–mediated β-catenin signaling, which are required for arterial gene upregulation (84, 85).

Hypoxia also plays a role in vascular differentiation. Recent studies have shown that hypoxia upregulates Dll4 expression and increases Notch signaling in a process requiring the vasoactive hormone adrenomedullin. Furthermore, hypoxia-mediated Notch activation subsequently upregulates the arterial marker genes Depp, Cx40, Cxcr4, and Hey1 (86, 87).

Because arterial venous specification is acquired through stepwise time-sensitive signals during development, each single step of adding growth factors, hemodynamic shear stress, or hypoxia alone is unlikely to achieve fully functional arterial phenotypes. Recent research further advanced this field by generating an EphrinB2–tdTomato/EphB4–GFP dual reporter human embryonic stem cell line using CRISPR/Cas9 (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/caspase-9) technology. This cell line was used to screen for small molecules and growth factors that gave rise to the largest numbers of arterial EC progenitors (EphrinB2+EphB4−). This research group then developed a xeno-free “five-factor” protocol that combines fibroblast growth factor 2, VEGFA, SB431542 (a transforming growth factor β inhibitor), resveratrol (a Notch agonist), and L690an (an inositol monophosphatase inhibitor) in a stepwise fashion, leading to significantly improved arterial EC differentiation compared with standard culture procedures (88).

6. REMAINING ISSUES AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Vascular development has been extensively studied in lower animals such as zebrafish and mice. These model systems provide abundant information for better understanding of vascular diseases and better methods to differentiate stem cells toward arterial or venous ECs. However, translation of this knowledge is still in its infancy. Importantly, molecular markers and transcriptional programs identified during early vascular development often disappear in adult vessel, as shown in recent studies. Some of the most frequently used arterial markers in the literature, such as Hey1, Hey2, Jag1, Jag2, Nrp1, Notch1, Dll1, and Cxcr4, do not differ in their expression levels in the adult artery and vein. Therefore, identifying the genetic programs that are key for maintenance of the adult vessel identity seems to be the next important area for inquiry. Astonishingly, a clean data set describing the molecular profiles of adult human artery and vein endothelium is still lacking. Because cultured primary human ECs gradually lose their identity, and because there is significant genetic heterogeneity among individuals, fresh isolated samples from healthy arteries and veins of the same individual represent the cleanest data set. Despite some logistical hurdles, obtaining clean, EC-only mRNA samples from adult arterial and venous specimens in humans would yield a wealth of information regarding the programs needed to maintain EC specification and phenotype.

Arterial venous specification and maturation involve complex genetic and epigenetic interactions with environmental cues that also require correct timing. These cues include growth factors, cell–cell interactions, ECM, biomechanical forces, and oxygen levels. Studies of how these factors combine at different time points to influence arterial venous differentiation are much needed. Compared with arterial EC differentiation, venous EC differentiation has been studied much less intensively. This knowledge gap is important from a translational point of view, because venous ECs seem to have a unique genetic and functional profile that protects them from many vascular diseases.

Most current methods for differentiation of ECs from embryonic or pluripotent stem cells probably yield an EC population that is neither arterial nor venous. It is important that future studies compare iPSC-derived ECs with in vivo arterial and venous EC gene expression profiles in order to fine-tune our understanding of EC derivation from these primitive stem cell sources. But beyond their gene expression profiles, these cells’ functional outcomes are the most relevant to tissue engineering applications. For example, controlled experiments with iPSC-derived venous versus arterial ECs have not yet been done to determine which specification produces the best long-term outcome in vivo. Such studies are needed to improve our understanding.

A better understanding of vein graft adaptation to arterial circulation is also critical for improving the long-term patency of these grafts. The significant risk of graft failure after vein grafting into the arterial system suggests limited plasticity of adult venous identity. Understanding and then manipulating the pathways driving arterial venous differentiation may provide a way to improve clinical outcomes of vein grafting procedures, which would have a huge overall health care benefit. Because veins used as bypass grafts lack nerves, future research on providing substitutes for innervation of vein grafts, or developing bioengineering tools that deliver nerve-like signals to the grafted vessel, may be a promising avenue to improve current vascular grafting strategies.

In summary, significant advances have been made in arterial venous differentiation in the past few years, and much more research to address the remaining challenges is under way. In the future, these advances will lead to the availability of iPSC-derived functional arterial and venous ECs, providing a better cell source for regenerative medicine, vascular biology research, and drug development.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for support from an American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant (12SDG12050083 to G.D.), the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R21HL102773 and R01HL118245 to G.D.), and the National Science Foundation (CBET-1263455 and CBET-1350240 to G.D.). In addition, we acknowledge support from NIH R01-HL127386, from NIH R01-HL128506, and from the Connecticut Stem Cell Institute (grant number 15-RMB-YALE-07) (all to L.E.N.).

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

L.E.N. is a founder and shareholder in Humacyte, Inc., which is a regenerative medicine company. Humacyte produces engineered blood vessels from allogeneic smooth muscle cells for vascular surgery. L.E.N.’s spouse has equity in Humacyte, and L.E.N. serves on Humacyte’s Board of Directors. L.E.N. is an inventor on patents that are licensed to Humacyte and that produce royalties for L.E.N. L.E.N. has received an unrestricted research gift to support research in her laboratory at Yale University. Humacyte did not fund these studies, and Humacyte did not influence the conduct, description, or interpretation of the findings in this report. G.D. is not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Wang HU, Chen ZF, Anderson DJ. 1998. Molecular distinction and angiogenic interaction between embryonic arteries and veins revealed by ephrin-B2 and its receptor Eph-B4. Cell 93:741–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones EA. 2011. The initiation of blood flow and flow induced events in early vascular development. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol 22:1028–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shin D, Garcia-Cardena G, Hayashi S, Gerety S, Asahara T, et al. 2001. Expression of ephrinB2 identifies a stable genetic difference between arterial and venous vascular smooth muscle as well as endothelial cells, and marks subsets of microvessels at sites of adult neovascularization. Dev. Biol 230:139–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herzog Y, Guttmann-Raviv N, Neufeld G. 2005. Segregation of arterial and venous markers in subpopulations of blood islands before vessel formation. Dev. Dyn 232:1047–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhong TP, Childs S, Leu JP, Fishman MC. 2001. Gridlock signalling pathway fashions the first embryonic artery. Nature 414:216–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindskog H, Kim YH, Jelin EB, Kong Y, Guevara-Gallardo S, et al. 2014. Molecular identification of venous progenitors in the dorsal aorta reveals an aortic origin for the cardinal vein in mammals. Development 141:1120–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herbert SP, Huisken J, Kim TN, Feldman ME, Houseman BT, et al. 2009. Arterial-venous segregation by selective cell sprouting: an alternative mode of blood vessel formation. Science 326:294–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Red-Horse K, Ueno H, Weissman IL, Krasnow MA. 2010. Coronary arteries form by developmental reprogramming of venous cells. Nature 464:549–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kohli V, Schumacher JA, Desai SP, Rehn K, Sumanas S. 2013. Arterial and venous progenitors of the major axial vessels originate at distinct locations. Dev. Cell 25:196–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu C, Hasan SS, Schmidt I, Rocha SF, Pitulescu ME, et al. 2014. Arteries are formed by vein-derived endothelial tip cells. Nat. Commun 5:5758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Val S, Black BL. 2009. Transcriptional control of endothelial cell development. Dev. Cell 16:180–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Val S 2011. Key transcriptional regulators of early vascular development. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 31:1469–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Val S, Chi NC, Meadows SM, Minovitsky S, Anderson JP, et al. 2008. Combinatorial regulation of endothelial gene expression by Ets and Forkhead transcription factors. Cell 135:1053–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dejana E, Taddei A, Randi AM. 2007. Foxs and Ets in the transcriptional regulation of endothelial cell differentiation and angiogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1775:298–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shutter JR, Scully S, Fan W, Richards WG, Kitajewski J, et al. 2000. Dll4, a novel Notch ligand expressed in arterial endothelium. Genes Dev 14:1313–18 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krebs LT, Xue Y, Norton CR, Shutter JR, Maguire M, et al. 2000. Notch signaling is essential for vascular morphogenesis in mice. Genes Dev 14:1343–52 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawson ND, Scheer N, Pham VN, Kim CH, Chitnis AB, et al. 2001. Notch signaling is required for arterial-venous differentiation during embryonic vascular development. Development 128:3675–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischer A, Schumacher N, Maier M, Sendtner M, Gessler M. 2004. The Notch target genes Hey1 and Hey2 are required for embryonic vascular development. Genes Dev 18:901–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Domenga V, Fardoux P, Lacombe P, Monet M, Maciazek J, et al. 2004. Notch3 is required for arterial identity and maturation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Genes Dev 18:2730–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duarte A, Hirashima M, Benedito R, Trindade A, Diniz P, et al. 2004. Dosage-sensitive requirement for mouse Dll4 in artery development. Genes Dev 18:2474–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quillien A, Moore JC, Shin M, Siekmann AF, Smith T, et al. 2014. Distinct Notch signaling outputs pattern the developing arterial system. Development 141:1544–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kokubo H, Miyagawa-Tomita S, Nakazawa M, Saga Y, Johnson RL. 2005. Mouse hesr1 and hesr2 genes are redundantly required to mediate Notch signaling in the developing cardiovascular system. Dev. Biol 278:301–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Villa N, Walker L, Lindsell CE, Gasson J, Iruela-Arispe ML, Weinmaster G. 2001. Vascular expression of Notch pathway receptors and ligands is restricted to arterial vessels. Mech. Dev 108:161–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawson ND, Vogel AM, Weinstein BM. 2002. sonic hedgehog and vascular endothelial growth factor act upstream of the Notch pathway during arterial endothelial differentiation. Dev. Cell 3:127–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kume T 2010. Specification of arterial, venous, and lymphatic endothelial cells during embryonic development. Histol. Histopathol 25:637–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lawson ND, Weinstein BM. 2002. Arteries and veins: making a difference with zebrafish. Nat. Rev. Genet 3:674–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinstein BM, Lawson ND. 2002. Arteries, veins, Notch, and VEGF. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol 67:155–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Tuyl M, Groenman F, Wang J, Kuliszewski M, Liu J, et al. 2007. Angiogenic factors stimulate tubular branching morphogenesis of sonic hedgehog–deficient lungs. Dev. Biol 303:514–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Visconti RP, Richardson CD, Sato TN. 2002. Orchestration of angiogenesis and arteriovenous contribution by angiopoietins and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). PNAS 99:8219–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lanner F, Sohl M, Farnebo F. 2007. Functional arterial and venous fate is determined by graded VEGF signaling and Notch status during embryonic stem cell differentiation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 27:487–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deng Y, Larrivee B, Zhuang ZW, Atri D, Moraes F, et al. 2013. Endothelial RAF1/ERK activation regulates arterial morphogenesis. Blood 121:3988–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hong CC, Peterson QP, Hong J-Y, Peterson RT. 2006. Artery/vein specification is governed by opposing phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase and MAP kinase/ERK signaling. Curr. Biol 16:1366–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hong CC, Kume T, Peterson RT. 2008. Role of crosstalk between phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and extracellular signal–regulated kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in artery-vein specification. Circ. Res 103:573–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ren B, Deng Y, Mukhopadhyay A, Lanahan AA, Zhuang ZW, et al. 2010. ERK1/2-Akt1 crosstalk regulates arteriogenesis in mice and zebrafish. J. Clin. Investig 120:1217–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wythe JD, Dang LTH, Devine WP, Boudreau E, Artap ST, et al. 2013. ETS factors regulate Vegf-dependent arterial specification. Dev. Cell 26:45–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mukouyama YS, Shin D, Britsch S, Taniguchi M, Anderson DJ. 2002. Sensory nerves determine the pattern of arterial differentiation and blood vessel branching in the skin. Cell 109:693–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mukouyama YS, Gerber HP, Ferrara N, Gu C, Anderson DJ. 2005. Peripheral nerve–derived VEGF promotes arterial differentiation via neuropilin 1–mediated positive feedback. Development 132:941–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lanahan A, Zhang X, Fantin A, Zhuang Z, Rivera-Molina F, et al. 2013. The neuropilin 1 cytoplasmic domain is required for VEGF-A-dependent arteriogenesis. Dev. Cell 25:156–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herzog Y, Kalcheim C, Kahane N, Reshef R, Neufeld G. 2001. Differential expression of neuropilin-1 and neuropilin-2 in arteries and veins. Mech. Dev 109:115–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moyon D, Pardanaud L, Yuan L, Bréant C, Eichmann A. 2001. Plasticity of endothelial cells during arterial-venous differentiation in the avian embryo. Development 128:3359–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones EAV, Yuan L, Breant C, Watts RJ, Eichmann A. 2008. Separating genetic and hemodynamic defects in neuropilin 1 knockout embryos. Development 135:2479–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Herpers R, van de Kamp E, Duckers HJ, Schulte-Merker S. 2008. Redundant roles for Sox7 and Sox18 in arteriovenous specification in zebrafish. Circ. Res 102:12–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cermenati S, Moleri S, Cimbro S, Corti P, Del Giacco L, et al. 2008. Sox18 and Sox7 play redundant roles in vascular development. Blood 111:2657–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pendeville H, Winandy M, Manfroid I, Nivelles O, Motte P, et al. 2008. Zebrafish Sox7 and Sox18 function together to control arterial-venous identity. Dev. Biol 317:405–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sacilotto N, Monteiro R, Fritzsche M, Becker PW, Sanchez-Del-Campo L, et al. 2013. Analysis of Dll4 regulation reveals a combinatorial role for Sox and Notch in arterial development. PNAS 110:11893–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chiang IK, Fritzsche M, Pichol-Thievend C, Neal A, Holmes K, et al. 2017. SoxF factors induce Notch1 expression via direct transcriptional regulation during early arterial development. Development 144:2629–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Corada M, Orsenigo F, Morini MF, Pitulescu ME, Bhat G, et al. 2013. Sox17 is indispensable for acquisition and maintenance of arterial identity. Nat. Commun 4:2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Foroud T, Koller DL, Lai D, Sauerbeck L, Anderson C, et al. 2012. Genome-wide association study of intracranial aneurysms confirms role of Anril and SOX17 in disease risk. Stroke 43:2846–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bilguvar K, Yasuno K, Niemela M, Ruigrok YM, von und zu Fraunberg M, et al. 2008. Susceptibility loci for intracranial aneurysm in European and Japanese populations. Nat. Genet 40:1472–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yasuno K, Bilguvar K, Bijlenga P, Low SK, Krischek B, et al. 2010. Genome-wide association study of intracranial aneurysm identifies three new risk loci. Nat. Genet 42:420–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen X, Qin J, Cheng C-M, Tsai M-J, Tsai SY. 2012. COUP-TFII is a major regulator of cell cycle and Notch signaling pathways. Mol. Endocrinol 26:1268–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chu M, Li T, Shen B, Cao X, Zhong H, et al. 2016. Angiopoietin receptor Tie2 is required for vein specification and maintenance via regulating COUP-TFII. eLife 5:e21032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arita Y, Nakaoka Y, Matsunaga T, Kidoya H, Yamamizu K, et al. 2014. Myocardium-derived angiopoietin-1 is essential for coronary vein formation in the developing heart. Nat. Commun 5:4552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Davis RB, Curtis CD, Griffin CT. 2013. BRG1 promotes COUP-TFII expression and venous specification during embryonic vascular development. Development 140:1272–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carmeliet P, Tessier-Lavigne M. 2005. Common mechanisms of nerve and blood vessel wiring. Nature 436:193–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carmeliet P 2003. Blood vessels and nerves: common signals, pathways and diseases. Nat. Rev. Genet 4:710–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li W, Kohara H, Uchida Y, James JM, Soneji K, et al. 2013. Peripheral nerve–derived CXCL12 and VEGF-A regulate the patterning of arterial vessel branching in developing limb skin. Dev. Cell 24:359–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pardanaud L, Pibouin-Fragner L, Dubrac A, Mathivet T, English I, et al. 2016. Sympathetic innervation promotes arterial fate by enhancing endothelial ERK activity. Circ. Res 119:607–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Buschmann I, Pries A, Styp-Rekowska B, Hillmeister P, Loufrani L, et al. 2010. Pulsatile shear and Gja5 modulate arterial identity and remodeling events during flow-driven arteriogenesis. Development 137:2187–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Le Noble F, Moyon D, Pardanaud L, Yuan L, Djonov V, et al. 2004. Flow regulates arterial-venous differentiation in the chick embryo yolk sac. Development 131:361–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chong DC, Koo Y, Xu K, Fu S, Cleaver O. 2011. Stepwise arteriovenous fate acquisition during mammalian vasculogenesis. Dev. Dyn 240:2153–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Udan RS, Vadakkan TJ, Dickinson ME. 2013. Dynamic responses of endothelial cells to changes in blood flow during vascular remodeling of the mouse yolk sac. Development 140:4041–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kudo FA, Muto A, Maloney SP, Pimiento JM, Bergaya S, et al. 2007. Venous identity is lost but arterial identity is not gained during vein graft adaptation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 27:1562–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang M, Collins MJ, Foster TR, Bai H, Hashimoto T, et al. 2017. Eph-B4 mediates vein graft adaptation by regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. J. Vasc. Surg 65:179–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Muto A, Yi T, Harrison KD, Dávalos A, Fancher TT, et al. 2011. Eph-B4 prevents venous adaptive remodeling in the adult arterial environment. J. Exp. Med 208:561–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cui X, Lu YW, Lee V, Kim D, Dorsey T, et al. 2015. Venous endothelial marker COUP-TFII regulates the distinct pathologic potentials of adult arteries and veins. Sci. Rep 5:16193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lin Y, Jiang W, Ng J, Jina A, Wang RA. 2014. Endothelial ephrin-B2 is essential for arterial vasodilation in mice. Microcirculation 21:578–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Braun J, Hoffmann SC, Feldner A, Ludwig T, Henning R, et al. 2011. Endothelial cell ephrinB2-dependent activation of monocytes in arteriosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 31:297–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Castillo-Díaz SA, Garay-Sevilla ME, Hernández-González MA, Solís-Martínez MO, Zaina S. 2010. Extensive demethylation of normally hypermethylated CpG islands occurs in human atherosclerotic arteries. Int. J. Mol. Med 26:691–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhou X, Xiao Y, Mao Z, Huang J, Geng Q, et al. 2015. Soluble Jagged-1 inhibits restenosis of vein graft by attenuating Notch signaling. Microvasc. Res 100:9–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xiao YG, Wang W, Gong D, Mao ZF. 2014. γ-Secretase inhibitor DAPT attenuates intimal hyperplasia of vein grafts by inhibition of Notch1 signaling. Lab. Investig 94:654–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fukuda D, Aikawa E, Swirski FK, Novobrantseva TI, Kotelianski V, et al. 2012. Notch ligand δ–like 4 blockade attenuates atherosclerosis and metabolic disorders. PNAS 109:E1868–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nakano T, Fukuda D, Koga J, Aikawa M. 2016. Delta-like ligand 4–Notch signaling in macrophage activation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 36:2038–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Crist AM, Young C, Meadows SM. 2017. Characterization of arteriovenous identity in the developing neonate mouse retina. Gene. Expr. Patterns 23/24:22–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dancu MB, Tarbell JM. 2007. Coronary endothelium expresses a pathologic gene pattern compared to aortic endothelium: correlation of asynchronous hemodynamics and pathology in vivo. Atherosclerosis 192:9–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Aranguren XL, Agirre X, Beerens M, Coppiello G, Uriz M, et al. 2013. Unraveling a novel transcription factor code determining the human arterial-specific endothelial cell signature. Blood 122:3982–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Geenen IL, Molin DG, van den Akker NM, Jeukens F, Spronk HM, et al. 2015. Endothelial cells (ECs) for vascular tissue engineering: Venous ECs are less thrombogenic than arterial ECs. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med 9:564–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zahr A, Alcaide P, Yang J, Jones A, Gregory M, et al. 2016. Endomucin prevents leukocyte–endothelial cell adhesion and has a critical role under resting and inflammatory conditions. Nat. Commun 7:10363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Palpant NJ, Pabon L, Friedman CE, Roberts M, Hadland B, et al. 2017. Generating high-purity cardiac and endothelial derivatives from patterned mesoderm using human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Protoc 12:15–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lian X, Bao X, Al-Ahmad A, Liu J, Wu Y, et al. 2014. Efficient differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells to endothelial progenitors via small-molecule activation of WNT signaling. Stem Cell Rep 3:804–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Obi S, Yamamoto K, Shimizu N, Kumagaya S, Masumura T, et al. 2009. Fluid shear stress induces arterial differentiation of endothelial progenitor cells. J. Appl. Physiol 106:203–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Masumura T, Yamamoto K, Shimizu N, Obi S, Ando J. 2009. Shear stress increases expression of the arterial endothelial marker ephrinB2 in murine ES cells via the VEGF–Notch signaling pathways. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 29:2125–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sivarapatna A, Ghaedi M, Le AV, Mendez JJ, Qyang Y, Niklason LE. 2015. Arterial specification of endothelial cells derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells in a biomimetic flow bioreactor. Biomaterials 53:621–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yurugi-Kobayashi T, Itoh H, Schroeder T, Nakano A, Narazaki G, et al. 2006. Adrenomedullin/cyclic AMP pathway induces Notch activation and differentiation of arterial endothelial cells from vascular progenitors. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 26:1977–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yamamizu K, Matsunaga T, Uosaki H, Fukushima H, Katayama S, et al. 2010. Convergence of Notch and β-catenin signaling induces arterial fate in vascular progenitors. J. Cell Biol 189:325–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lanner F, Lee KL, Ortega GC, Sohl M, Li X, et al. 2013. Hypoxia-induced arterial differentiation requires adrenomedullin and Notch signaling. Stem Cells Dev 22:1360–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tsang KM, Hyun JS, Cheng KT, Vargas M, Mehta D, et al. 2017. Embryonic stem cell differentiation to functional arterial endothelial cells through sequential activation of ETV2 and NOTCH1 signaling by HIF1α. Stem Cell Rep 9:796–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhang J, Chu LF, Hou Z, Schwartz MP, Hacker T, et al. 2017. Functional characterization of human pluripotent stem cell–derived arterial endothelial cells. PNAS 114:E6072–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]