Abstract

Background

Studies show patients recall less than half the information given by their physicians. Use of video in medicine increases patient comprehension and satisfaction and decreases anxiety. However, studies have not elaborated on video content.

Objective

To use principles of learning with multimedia to improve the Mohs surgery consultation.

Materials & Methods

We developed 2 informational videos on Mohs surgery: traditional vs narrative. The focus of the traditional video was purely didactic. The narrative video included patient testimonials, patient-physician interaction, and animations. New Mohs surgery patients viewed either the traditional (n=40) or the narrative video (n=40). Existing Mohs surgery patients (n=40) viewed both videos. Both groups answered questionnaires about their satisfaction.

Results

For new Mohs surgery patients, no significant difference was found between the traditional and the narrative video group as respondent satisfaction was high for both video formats. For existing Mohs surgery patients, all respondents (100%) reported that videos were helpful for understanding Mohs surgery, however, the majority would recommend the narrative over the traditional format (72.5% versus 27.5%, p=0.01).

Conclusion

Technology is useful for patient education, as all patients preferred seeing a video to no video. Further research is needed to optimize effective multimedia use in patient education.

Introduction

Patients recall less than half the information delivered to them by their physicians, which suggests patient education is an area of medicine that can be improved.1–3 Technological advances may be useful to bridge this gap in patient–physician communication. Multimedia videos in medicine have been shown to increase patient comprehension and satisfaction while decreasing anxiety.4 Studies in diverse areas of medicine on the role of patient education videos have assessed outcomes including knowledge acquisition, patient satisfaction/comfort, and efficiency as measured by provider face-time.1–7

In the development of patient education videos, it is important to incorporate theories from the fields of education and cognitive psychology. For example, narrative research is increasingly relevant to the fields of education and medicine.8 Narrative inquiry or narrative research is an interdisciplinary methodology employed to analyze activities related to the use of stories of life experience, such as interviews, conversations, autobiographies or memoirs.8–16 Over the last decade in education, the “cognitive theory of multimedia learning” (CTML) has also evolved.17–19 Within the CTML framework, the following multimedia principles have emerged to enhance learning: presenting words and images together, presenting words as narration and learning to exclude extraneous material.19

The objective of this study was to use the principles of learning with multimedia to develop a video for patient education to modernize and supplement the traditional Mohs surgery consultation. Further, we investigated the delivery of information in a traditional vs. narrative approach to gauge patient preference in presentation style.

Methods

Mohs Educational Video development

Two educational videos on skin cancer and Mohs micrographic surgery were developed. The content of the video included an overview of non-melanoma skin cancers, risk factors, Mohs surgery technique, reconstruction options, risks of procedure, and typical pre- and postoperative instructions. Both videos were professionally produced using a video production consultant working with a dedicated video department for videotaping, audio recording, animation, and editing services (funded by the ASDS Cutting Edge Research Grant). The video types included:

-

1

Traditional video

The traditional video was only content-based with information presented in a static PowerPoint format with voiceover audio. The video duration was 4:06 minutes.

-

2

Narrative video

The narrative video included the identical factual content as the traditional video but incorporated multimedia principles such as video footage of Mohs surgery and tissue processing in the Mohs lab, animation, and patient–physician conversation during the Mohs consultation. The narrative video also provided testimonials from a male and female patient who shared their experience with skin cancer diagnosis, treatment consultation, and Mohs surgery. The narrative video duration was 6:31 minutes.

Study Design

Part I: New Mohs Surgery Patients

New patients presenting for Mohs surgery consultation to 1 of 3 Mohs surgeons were consecutively enrolled under an approved IRB protocol at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center during a 3-month period. Inclusion criteria included patients with a biopsy proven diagnosis of basal cell or squamous cell carcinoma. Patients with a history of prior Mohs surgery or non-English speakers were excluded. All patients had an initial intake with a Mohs nurse and then viewed the educational video on an Apple iPad. This was followed by a face to face consultation with a Mohs physician. All patients were given written information on skin cancer and Mohs surgery.

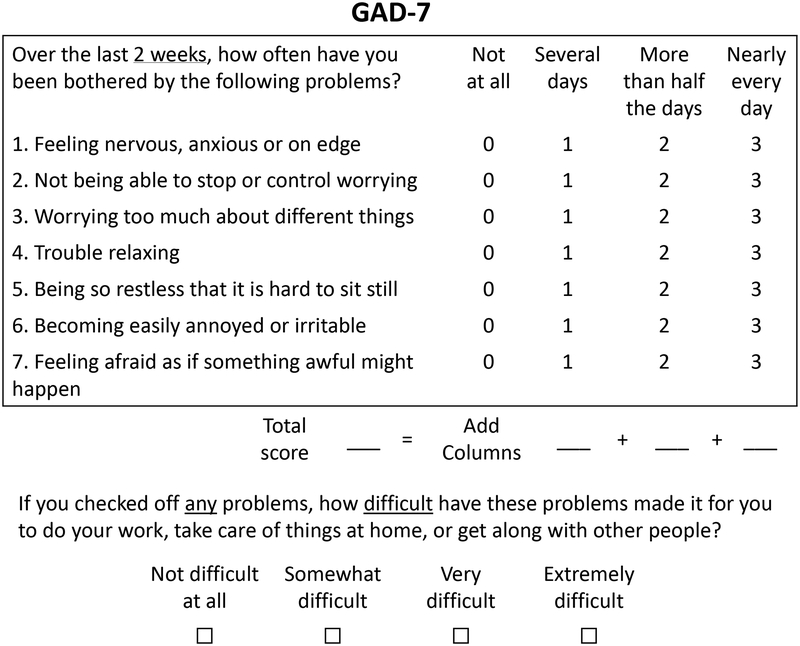

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder–7 question assessment tool (GAD-7) was administered to all patients to assess baseline anxiety level prior to administering the video. GAD-7 is a one-dimensional scale to assess symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) referred to in DSM-IV2 (Figure 1).20–21 The optimum cutoff for generalized anxiety disorder is a score greater or equal to 10.

Figure 1.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) scale

Scores: 0–4 minimal anxiety, 5–9 mild anxiety, 10–14 moderate anxiety, 15–25 severe anxiety.

The initial 40 patients viewed the traditional video and then the subsequent 40 patients viewed the narrative video. The patients were asked for general feedback and answered the following questions after viewing the video to assess satisfaction and comfort levels:

- On a scale of 1–5, how satisfied are you with the consultation video?

- 1 = completely unsatisfied; 5 = completely satisfied

- On a scale of 1–5, how comfortable are you with having Mohs surgery?

- 1 = completely uncomfortable; 5 = completely comfortable

Part II: Existing Mohs Surgery Patients

Existing Mohs surgery patients with prior history of Mohs surgery presenting with a new basal or squamous cell carcinoma were consecutively enrolled during their Mohs treatment visit. Non-English speakers were excluded. Patients filled out the GAD-7 prior to viewing the educational videos. The patients viewed both videos in succession on an iPad and then answered questions based on their past knowledge and experience with the Mohs procedure. The questions assessed if the videos were helpful for understanding Mohs surgery, which video was preferred for patient comfort, if the video content was sufficient, if video length appropriate, and worries about Mohs surgery. Patients were also given opportunity to write open ended comments or concerns. The viewing order of the two videos was switched half way through enrollment to mitigate potential viewer fatigue and bias related to viewing order. The first 20 patients viewed the traditional video first and then the narrative video. The next 20 patients viewed the narrative video first and then the traditional video.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics including relative frequencies, and standard deviations were used to describe the study participants and their feedback related to the video presentation types. Student’s t-tests and paired t-tests were used to assess differences in age by type of video (traditional versus narrative) for Part I and II of the interventions, respectively. In addition, one sample tests for proportions were used to determine if there was a preference for video presentation type compared to 0.5 (no preference, i.e., half of the group preferring preferring traditional and half preferring narrative). All analyses were performed with Stata v,14.2, Stata Corporation, College Station, TX.

Results

Eighty patients were enrolled in Part I (new Mohs surgery patients) and 40 patients were enrolled in Part II (existing Mohs surgery patients). Patient age, sex, skin cancer diagnosis, location and GAD-7 anxiety score are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patients viewing Mohs educational video: Patient and skin cancer characteristics and anxiety scores

| Part I: New pts Traditional video (n=40) |

Part I: New pts Narrative video (n=40) |

Part II: Existing pts video1/video2 (n=20) |

Part II: Existing pts video2/video1 (n=20) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior Mohs surgery | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Avg age | 61.9 | 59.3 | 71 | 69.2 |

| Female | 20 (50%) | 23 (58%) | 5 (25%) | 11 (55%) |

| %BCC (vs SCC) | 31/43 (72%) | 24/41 (59%) | 14/25 (56%) | 18/23 (78%) |

| Site: | ||||

| Head&neck | 30 (70%) | 36 (84%) | 15 (65%) | 22 (92%) |

| Trunk & extremity | 11 (26%) | 6 (14%) | 8 (35%) | 2 (8%) |

| Hands&feet | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| GAD-7 avg score | 2.45 | 1.98 | 1.7 | 3.1 |

| GAD-7 score range | 0–14 | 0–16 | 0–6 | 0–18 |

| No/minimal anxiety | 25 (62.5%) | 34 (85%) | 18 (90%) | 17 (85%) |

| Mild anxiety | 7 (17.5%) | 2 (5%) | 2 (10%) | 2 (10%) |

| Moderate anxiety | 1 (2.5%) | 3 (7.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Severe anxiety | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5%) |

Part I: New Mohs Surgery Patients response to video

In response to the question “How satisfied are you with the consultation video on a scale of 1–5?”, the traditional video group (n=40) reported an average of 4.7/5 and the narrative video group (n=40) reported an average of 4.6/5. In response to the question “How comfortable are you with having Mohs surgery on a scale of 1–5?”, the traditional video group responded with an average of 4.5/5 and the narrative video group responded with an average of 4.6/5, p=0.92. There was no significant difference between the 2 groups; notably patient satisfaction levels were high for both the traditional and narrative videos.

Part II: Existing Mohs Surgery Patients response to video

The responses from existing patients after watching both videos are detailed in Table 2. All patients (40/40) found watching a video helpful. Overall, the narrative approach was preferred with, 72.5% (29/40) reporting they would recommend the narrative video to another patient, while 27.5% (11/40) would recommend the traditional video, p=0.01. Those who watched the traditional video first were slightly more likely (83%) to recommend the narrative video, compared to those who viewed the narrative video first, p=0,11. For those who preferred the narrative video, comments described being able to relate to the actor in the testimonial and finding their experience to be comforting. Those who preferred the traditional video made comments describing their preference for straight facts without filler. More participants reported the narrative video was too long at 6:31 minutes compared to the traditional video 4:06 minutes.

Table 2.

Responses from existing Mohs surgery patients viewing Mohs educational videos

| Question | Part II: Traditional first Narrative second (n=20) |

Part II: Narrative first Traditional second (n=20) |

Overall |

|---|---|---|---|

| Was watching a video helpful for understanding Mohs surgery? | Yes: 20/20 No: 0/20 |

Yes: 20/20 No: 0/20 |

Yes: 40/40 No: 0/40 |

| Which video would you recommend for a patient having Mohs surgery for the first time to make them feel most comfortable? | Traditional: 3 (17%) Narrative: 17 (83%) |

Traditional: 8 (40%) Narrative: 12 (60%) |

Traditional: 11 (27.5%) Narrative: 29 (72.5%) |

| Were any concerns not addressed that you feel would be important to include? | Yes: 8 (40%) No: 12 (60%) |

Yes: 5 (25%) No: 15 (75%) |

Yes: 13 (32.5%) No: 27 (67.5%) |

| Was the right amount of information given? | Yes: 18/20 (90%) No: 2/20 (10%) |

Yes: 18/20 (90%) No: 2/20 (10%) |

Yes: 36 (90%) No: 4 (10%) |

| Did either video seem too long? | Yes: 6 (33%) No: 13 (68%) |

Yes: 7 (35%) No: 13 (65%) |

Yes: 13 (32.5%) No: 27 (67.5%) |

| If yes, which? | Traditional: 0 Narrative: 5 Both: 1 |

Traditional: 1 Narrative: 5 Both: 1 |

Traditional: 1 Narrative: 10 Both: 2 |

When patients were asked “What were you most worried about before Mohs surgery?” the coded free responses included scarring (13) followed by how dangerous the skin cancer itself was to their health (9). Others were most concerned about the surgery itself (5), the recovery process (3), and pain (1).

Overall patient feedback about videos

General comments and feedback about the videos from patients in Part I and II are listed in Table 3.

Table 3:

Selection of overall comments about Mohs educational video

Part I New Mohs surgery patients (traditional video group):

|

Part I New Mohs surgery patients (narrative video group):

|

Part II Existing Mohs surgery patients viewing traditional and narrative videos:

|

Discussion

The goal of this study was to improve the Mohs surgery consultation with a multifaceted educational approach utilizing modern technology to supplement face-to- face physician time. We focused on the development of the multimedia tool by comparing a traditional purely informational video with a narrative video containing patient-physician interaction, patient testimonial, and animation. Patients new to Mohs surgery in the traditional versus narrative video groups were both highly satisfied with the video and comfortable with Mohs surgery with no significant difference noted between the groups. However, when existing Mohs surgery patients were queried about video format and content preference, the narrative video was preferred by the majority. This experienced group of Mohs surgery patients all agreed that having the video (versus no video) was helpful to understanding Mohs surgery.

In order to design an effective educational tool for Mohs surgery patients and provide more targeted pre-surgical counseling, we must have an understanding of the common sources of worry in this population. In this study, patient expressed greatest concern about skin cancer diagnosis and scarring and some concern about the surgical procedure and associated recovery and pain. It is also important to differentiate patients’ specific worry about skin cancer and Mohs surgery from their overall baseline anxiety. Thus, the GAD-7 tool was used to assess baseline anxiety of this cohort. Although Mohs surgery patients presented to their consultation with varying degrees of baseline anxiety, the vast majority had minimal or mild anxiety. A patient-reported outcome tool will be useful to better quantify the impact of skin cancer from the patient’s perspective.22

Challenges all educators face in developing any learning tool is learner variability in terms of attention span, learning style, and education level. Furthermore, an ideal educational video would be succinct to minimize viewer fatigue. Most of the existing Mohs patients in this study reported the amount of information delivered was appropriate and that their concerns were addressed in the videos ranging in length from 4:06–6:30 minutes. However, opinions varied over specific video details. For instance, while some patients preferred the simple line drawings of repair options and found real life pictures to be upsetting, others requested to see more before and after photos. While some patients found the narrative story-telling to be helpful, others described it as “filler” and would have preferred facts and figures only. Given diversity of patient preference, perhaps customization to specific areas of patient concern is better than a “one size fits all” approach. In addition, implementing a customized interactive module may be superior for enhancing patient learning given that active learning is more effective than passive learning.

This study focused on the Mohs educational video content and comparison of content delivery within a video technology to assess patient satisfaction, comfort, and preference. Other dermatologic surgery studies have also shown that video technology has the potential to improve patient education and experience. Outcome measurements in these studies included patient knowledge acquisition, overall patient satisfaction, or clinic efficiency. Migden et al. instituted video modules for informed consent with the physician providing Mohs surgery information and the nurse post-operative wound instructions.5 In this study, multimedia was preferred by patients over physician/nurse alone and there was increased patient comprehension and clinic efficiency. In another study, Van Acker et al. instituted an instructional video on wound care that compared timing of video delivery to 2 groups: pre-surgery and post-surgery.6 A questionnaire of 10 knowledge-based questions was given either before or after Mohs surgery to 51 patients with non-melanoma skin cancer. This study concluded that the timing of video viewing did not change patient knowledge or wound care performance. Love et al. implemented a video for aiding patient decision making for treatment options of “uncomplicated” BCC.7 When comparing the consult only group with the video and consult group, this study found the video and consult group had greater gains in knowledge and satisfaction but there was no difference in the total consent time between groups.

The limitations of this study were cohort of patients at a cancer institution and that patients received face- to- face physician consultation and written information in addition to the Mohs educational video, both potentially confounding factors. It is also possible that patients felt a need to please or rate highly their consultation experience. In this particular study, we did not study clinical efficiency or patient comprehension or knowledge gain, which may affect patient satisfaction. However, we did find that using the iPad for education was simple, mobile, and user friendly for both patients and staff. One could consider adding the educational video to a patient portal or website that could be viewed in advance to increase efficiency.

In summary, technology is useful for patient education, as shown by the fact that all patients preferred seeing a video to no video. Ultimately a balance is needed between offering a comforting narrative versus setting realistic expectations about the Mohs procedure and associated risks in a succinct manner. In the changing US healthcare environment and advances in technology, methods of teaching that incorporate technology are needed to efficiently deliver high quality care and augment patient education, decision-making, and ultimately satisfaction.

Acknowledgement:

Recipient of 2015 ASDS Cutting Edge Research Grant; funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748

The authors wish to acknowledge Steven Jacobs, Eileen Flores, Christa Mathews, Miriam Amilcar, MSKCC Mohs team and MSKCC video and graphics department for their help in this project

Footnotes

The authors have indicated no significant interest with commercial supporters.

Note: supplementary video files can be provided for reference at the reviewer’s request.

References

- 1.Varkey P, Sathananthan A, Scheifer A, Bhagra S, Fujiyoshi A, Tom A, Murad MH. Using quality-improvement techniques to enhance patient education and counseling of diagnosis and management. Qual Prim Care. 2009;17(3):2015–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hutson MM, Blaha JD. Patients’ recall of preoperative instruction for informed consent for an operation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1991;73:160–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleishman M, Garcia C. Informed consent in dermatologic surgery. Dermaol Surg 2003; 29:952–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson EAH, Makoul G, Bojarski EA, et al. Comparative analysis of print and multimedia health materials: A review of the literature. Patient education and counseling 2012;89:7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Migden M, Chavez-Frazier A, Nguyen T. The use of high definition video modules for delivery of informed consent and wound care education in the Mohs surgery unit. Semin Cutan. Med Surg. 2008;27:89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Acker MM, Kuriata MA. Video education provides effective wound care instruction pre- or post-Mohs micrographic surgery. J Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology, 2014; 7(41): 43–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Love EM, Manalo IF, Chen SC, Chen KH, Stoff BK. A video-based educational pilot for basal cell carcinoma (BCC) treatment: A randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016;74:477–83.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salevati Sara. Abstract. The role of narrative in patient-clinician communication Presented at CHI (computer-human interaction): Changing perspectives Paris, France 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Labov W. (2006). Narrative pre-construction. Narrative Inquiry, 16(1), 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith CP. (2000). Content analysis and narrative analysis In: Reis HT, Judd CM, eds. Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnstone B. (2006). A new role for narrative in variationist sociolinguistics. Narrative Inquiry, 16(1), 46–55. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Josselson R. (2006). Narrative research and the challenge of accumulating knowledge. Narrative Inquiry, 16(1), 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coffey A & Atkinson P. (1996) Making sense of qualitative data. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clandinin DJ. (Ed.). (2007). Preface In Handbook of narrative inquiry: Mapping a methodology (pp. ix–xvii). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charon Rita. Annals of Internal Medicine. Narrative Medicine: Form, Function, and Ethics. Vol 134, No 1 2 January 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Labov William (1972). Some principles of linguistic methodology. Language in Society, 1, pp 97–120 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rieber LP. (1990), ‘Animation in computer-based instruction’, Educational technology Research and Development 38, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayer RE. (2001), Multimedia Learning, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayer RE., ed. (2005), The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, U.K. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruiz MA, Zamorano E, Garcia-Campayo J, Pardo A, Freire O, and Rejas J.: Validity of the GAD-7 scale as an outcome measure of disability in patients with generalized anxiety disorders in primary care. J Affect Disord 2011; 128: pp. 277–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, and Lowe B.: A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166: pp. 1092–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee EH, Klassen AF, Lawson JL, Cano SJ, Scott AM, Pusic AL. Patient experiences and outcomes following facial skin cancer surgery: a qualitative study. Australas J Dermatol 2016. epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]