Abstract

Although phylogenetically unrelated, human hepatitis viruses share an exclusive or near exclusive tropism for replication in differentiated hepatocytes. This narrow tissue tropism may contribute to the restriction of the host ranges of these viruses to relatively few host species, mostly nonhuman primates. Nonhuman primate models thus figure prominently in our current understanding of the replication and pathogenesis of these viruses, including the enterically transmitted hepatitis A virus (HAV) and hepatitis E virus (HEV), and have also played major roles in vaccine development. This review draws comparisons of HAV and HEV infection from studies conducted in nonhuman primates, and describes how such studies have contributed to our current understanding of the biology of these viruses.

Although taxonomy remains controversial, more than 250 distinct species of nonhuman primates (NHPs) are likely to exist, and new NHP species continue to be recognized every year. Only those species held commonly in zoos or used routinely in biomedical or toxicology research have been studied comprehensively for their ability to support infection with any of the five viruses that cause hepatitis in humans. Nonetheless, multiple NHP species are known to be permissive for infection with these human viruses, and in some cases serve as natural hosts for identical or very closely related viruses. As a group, with the exception of genotypes 3 (gt)3 and gt4 of hepatitis E virus (HEV), human hepatitis viruses share a generally narrow host species range. In part, this may reflect their shared cellular tropism for differentiated hepatocytes, a highly specialized cell type. None of these viruses replicate productively in wild-type mice, in contrast to many other pathogenic human viruses.

Genetically, chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) are the NHP species most closely related to humans (Fig. 1). Not surprisingly, they can be readily infected experimentally with each of the five human hepatitis viruses, with pathologic consequences generally very similar to those in humans. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) has the most tightly restricted host range among these viruses, and other than humans is capable of infecting only chimpanzees (Lanford et al. 2011b). Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis delta virus (HDV), which replicates productively only in HBV-infected cells, also has a narrow host range. However, in addition to the great apes, some Old World primates, including gibbons and some baboon species, are susceptible to infection with human HBV (Bancroft et al. 1977; Kedda et al. 2000). The host ranges of the enterically transmitted hepatitis A virus (HAV) and HEV are wider yet, as both viruses are capable of infecting New World monkeys, including marmosets, tamarins, and owl monkeys, in addition to the great apes and Old World monkeys (Fig. 1). Because of their close genetic relationship to humans, chimpanzees offer a number of advantages for studying infection with human hepatitis viruses. However, ethical concerns, costs, and changes in research policies have for all intents and purposes eliminated the use of chimpanzees in such studies (Altevogt et al. 2011). Here, we provide a broad overview of NHP models of hepatitis A and E and the information that has accumulated from such studies.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic relationships of nonhuman primates (NHPs) used commonly for studies of hepatitis viruses and known susceptibility to specific viruses. Commonly accepted dates of species divergence are shown (mya = millions of years ago). Note that only mice with genetic deficiencies in innate immune signaling pathways, and not wild-type mice, are susceptible to hepatitis A virus (HAV), and that hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections in baboons may be restricted to certain species (Chacma baboons). All of the great apes, Old World, and New World NHPs shown here (with the possible exception of squirrel monkeys) have been found to have naturally acquired antibodies reactive to HAV (Deinhardt and Deinhardt 1984), and thus may be susceptible to infection with the virus. A broader range of NHP species than those shown here is also likely to be susceptible to hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection.

HEPATITIS A

HAV is spread primarily by fecal–oral transmission. The virus induces an acute inflammatory disease of the liver and has a worldwide distribution. In many developing countries, greater than 90% of children have been infected before the age of 10, most without clinically recognizable signs of liver disease. In more developed countries, there is an increasing trend for all children to be vaccinated, as this dramatically reduces the risk of exposure in the rest of the population (see Shouval 2018). An emerging problem exists in countries with intermediate endemicity where infection is uncommon because of improved water treatment and hygiene, but where adults without previous exposure become infected during sporadic outbreaks, typically with clinically evident disease (see Jacobsen 2018). Although hepatitis A is normally self-limited, in adults it usually causes significant morbidity, with jaundice in 40%–70% (Lemon 1985; see Shin and Jeong 2018). Following initial recovery, symptoms may relapse in up to 10% of individuals, extending illness for a few weeks to months. Fatal hepatic failure occurs, but in less than 1% of cases.

HAV is a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA virus classified within the Picornaviridae family (Ehrenfeld et al. 2010) in the Hepatovirus genus, a genus now known to include a number of closely related viral species that infect a diversity of small mammals (Drexler et al. 2015). Its RNA genome is approximately 7.5 kb in length. The 5′ terminus of the RNA lacks a typical cap structure and is covalently linked to a small viral protein, VPg (or 3B). The genome encodes a single large polyprotein, the translation of which is controlled by an internal ribosome entry site (IRES). The 3′ end of the genome contains a short untranslated segment terminating in a poly(A) tail. The polyprotein is processed to yield 10 mature viral proteins, including four structural proteins that form the capsid (VP4, VP2, VP3, and VP1pX) and six nonstructural proteins that are essential for replication of the RNA genome (2B, 2C, 3A, 3B [VPg], 3Cpro [a cysteine protease], and 3Dpol) (RNA-dependent RNA polymerase) (Lemon et al. 2017). HAV is unique among the hepatitis viruses in that it can be relatively easily adapted to growth in conventional mammalian cell cultures. The virus is noncytopathic, both in vivo and in cell culture, and is released from infected cells without cell lysis. Recent studies have shown that HAV has an unusual dual lifestyle, with naked, nonenveloped virions excreted in feces, and quasi-enveloped virions cloaked in host membranes (eHAV) circulating in the blood (Feng et al. 2013, 2014). Interestingly, HEV resembles HAV in this aspect (Yamada et al. 2009; Qi et al. 2015; Yin et al. 2016).

Early Development of NHP Models of Hepatitis A

Human HAV is capable of infecting a variety of Old World and New World NHPs, including chimpanzees (Dienstag et al. 1975; Maynard et al. 1975a), rhesus and cynomolgus macaques (Shevtsova et al. 1988; Amado et al. 2010), African green monkeys (Shevtsova et al. 1988), marmosets and tamarins (Maynard et al. 1975b; Provost and Hilleman 1978), and owl monkeys (Fig. 1) (Lemon et al. 1982). In the past, natural infections with human strains of HAV occurred frequently in captive NHPs, presumably through interactions with caretaking staff or, in some cases, exposure to contaminated water and flooding (Dienstag et al. 1976a). However, at least one strain recovered from an NHP appears to be a true Old World monkey virus. The genome of the AGM-27 virus, recovered from an infected African green monkey, varies in its nucleotide sequence in a manner that impacts antigenic structure of the capsid and perhaps species-specific pathogenicity (Emerson et al. 1996; Arankalle and Ramakrishnan 2009). HAV was experimentally transmitted to tamarins (Saquinus sp.) over 50 years ago (Deinhardt et al. 1967), and has since been studied extensively in tamarins, marmosets, chimpanzees, and owl monkeys (Mathiesen et al. 1980; Asher et al. 1995; Lanford et al. 2011a). Very recent studies have also shown susceptibility in mice with genetic deficits in the induction of type I interferon (IFN) responses (Hirai-Yuki et al. 2016; see Hirai-Yuki et al. 2018), allowing experimental expansion of the host range.

HAV was first identified by electron microscopy in the feces of experimentally infected human prisoner volunteers (Feinstone et al. 1973; Feinstone 2018). Prior to this groundbreaking discovery, the disease had been transmitted to tamarins, but the virus could not be detected (Deinhardt et al. 1967; Holmes et al. 1969). Subsequent to identification of the virus and the development of early serologic assays for an antibody to it, a series of studies in experimentally infected chimpanzees, tamarins/marmosets, and owl monkeys firmly established the hepatotropic nature of HAV (Maynard et al. 1975a; Dienstag et al. 1976b; Schulman et al. 1976; Schaffner et al. 1977; Keenan et al. 1984; Lanford et al. 2011a). Acute inflammatory liver injury was found to occur coincident with the appearance of antibodies to the virus 2–3 weeks postinfection (Fig. 2). Fecal shedding of virus and viremia was present throughout much of this preclinical phase of the infection (Cohen et al. 1989; Taylor et al. 1993). NHPs were shown to be susceptible to infection by oral as well as intravenous inoculation of virus with little difference in outcome. Intravenous challenge was used in most studies because the required infectious dose for oral infection is thousands-of-fold greater in comparison to intravenous infection of chimpanzees or tamarins/marmosets (Purcell et al. 2002). In tamarins (Saguinus mystax) inoculated intravenously, the time to first elevation of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activity, a reliable marker of hepatic inflammation, was inversely related to the infectious dose of the inoculum (Gust and Feinstone 1988).

Figure 2.

Acute hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection in a chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes). (A) Percutaneous liver biopsy taken 21 days after intravenous (i.v.) inoculation of HM175 virus. There is moderate portal inflammation with hemosiderin-laden macrophages and early piecemeal necrosis with erosion of the limiting plate. (B) Acute HAV infection in a chimpanzee inoculated i.v. with a human fecal extract containing the MS1 strain of HAV. Fecal virus shedding detected by solid-phase radioimmunossay (bottom panel) preceded maximal liver enzyme elevation and appearance of anti-HAV antibodies detected in a blocking immunoassay. Total serum bilirubin was 0.1 mg/dL at peak elevation of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGTP) elevations. This study was performed in 1978 at the Laboratory of Experimental Medicine and Surgery in Primates.

Large quantities of virus were detected in bile from infected chimpanzees (Schulman et al. 1976), suggesting that virus shed in the feces may be derived primarily from the liver. Other studies in NHPs revealed the presence of viral antigen within hepatocytes and hepatic Kupffer cells with some detection in spleen, lymph nodes, and the kidney (Mathiesen et al. 1978; Shimizu et al. 1978). Histopathologic examination of the liver revealed extensive inflammatory infiltrates, typically most prominent in the periportal regions of the liver, occasionally with periportal piecemeal necrosis (Fig. 2A) (see also Cullen and Lemon 2018 for a description of the pathology of HAV infection in NHPs). Electron microscopy revealed virus-like particles in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes, in some cases associated with membranous vesicles (Schulman et al. 1976; Taylor et al. 1993). Efforts to document an enteric site of virus replication were generally negative, although in one study involving orally infected owl monkeys (Aotus trivirgatus), HAV antigen was detected by a seemingly reliable immunofluorescent staining procedure in crypt cells of the ileum (Mathiesen et al. 1978, 1980; Asher et al. 1995). Small amounts of the virus have been found within saliva from chimpanzees (Cohen et al. 1989), the source of which is uncertain.

This large body of work in NHP effectively defined the virology parameters of acute HAV infection. However, these studies preceded the development of sensitive nucleic acid amplification methods for detection of viruses. A more recent study using contemporary RT-qPCR methods for detection of HAV in the liver, serum, and feces of chimpanzees that were either experimentally infected by intravenous inoculation of virus, or by exposure to an acutely infected cage-mate, generally confirmed these early findings (Lanford et al. 2011a). However, these recent studies showed that viral RNA remains present in the liver, and is shed in feces in decreasing amounts, over many months following the appearance of anti-HAV antibody and apparent resolution of the infection (Fig. 3). Whether infectious virus is associated with this RNA, possibly complexed with antibody, is not known. In aggregate, however, comparisons with earlier experimental infections in humans suggest that HAV pathogenicity is very similar in these NHPs and humans, albeit milder in NHPs with less hepatic inflammation and the absence of icterus (Havens 1946; Krugman et al. 1959; Boggs et al. 1970; Feinstone et al. 1973).

Figure 3.

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection in chimpanzees following intravenous (i.v.) viral challenge. (A) HAV RNA detection (green) by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) in biopsies of liver from chimpanzee 4x0395 14 weeks before (left) and 3 weeks (right) after i.v. inoculation of HM175 virus. At 3 weeks, abundant viral RNA is present within the cytoplasm of numerous hepatocytes surrounding an inflammatory infiltrate. (Image courtesy of David R. McGivern.) (B) Persistence of intrahepatic HAV RNA following acute infection in a chimpanzee (4x0293). HAV RNA was quantified in serum (red line), liver (green line), and feces (blue line) by RT-qPCR. Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels are indicated by the gray shaded area. IgM anti-HAV and total anti-HAV are shown as positive or negative (+ or −) at the top of the panel. (From Lanford et al. 2011a; adapted, with permission, from the authors.)

Fulminant hepatitis is a rare complication of infection in humans and has been observed in a single infected chimpanzee (Theamboonlers et al. 2012). Importantly, unlike other viruses that cause hepatitis in humans, HAV is not capable of establishing long-term persistent infections, either in humans or in NHPs. However, fecal HAV shedding may persist for months in infected infants (Rosenblum et al. 1991).

NHP Infections with Cell Culture–Passaged and Recombinant HAV Variants

A series of early studies in NHPs explored the potential for an attenuated HAV vaccine based on the reduced virulence of virus passaged in cell culture. Wild-type HAV replicates poorly in mammalian cell lines (Daemer et al. 1981; Binn et al. 1984). The virus was first isolated in cell culture after serial passage in vivo in tamarins/marmosets (Provost and Hilleman 1979). Later studies showed that it is possible to isolate virus directly from human feces (usually after many days or weeks in culture), and that with serial passage the virus adapts, achieving a more rapid replication phenotype and higher virus yields, and in some cases cytopathic effects (Daemer et al. 1981; Lemon et al. 1991). Nucleotide changes in the nonstructural 2B protein coding region and the 5′ IRES sequence (Jansen et al. 1988; Funkhouser et al. 1994) are associated with adaptation and a loss of virulence in chimpanzees and owl monkeys (Feinstone et al. 1983; Provost et al. 1983; Karron et al. 1988; Taylor et al. 1993). Whereas this suggested that it might be possible to develop an attenuated HAV vaccine similar to the Sabin live oral poliovaccine, an attenuated vaccine candidate exhibited strongly reduced replication in vivo and poor immunogenicity in human clinical trials (Midthun et al. 1991), resulting in the abandonment of this vaccine strategy in favor of inactivated vaccines. Although attenuated vaccines have not been pursued in most countries, China has licensed a live attenuated HAV vaccine (Mao et al. 1991; Binn and Lemon 2010).

Not all cell culture–adapted viruses are attenuated in virulence, however, and attenuation may vary by NHP species. The HM175 strain of HAV was found to be attenuated for chimpanzees, inducing less ALT elevation and shedding less virus than wild-type virus, but not tamarins/marmosets after being passaged 21 times in African green monkey kidney cells (Karron et al. 1988). However, it was attenuated in both NHP species after 32 passages. In another study, an independent isolate of the HM175 strain was found to be virulent in owl monkeys (A. trivirgatus) at the 15th cell culture passage level (Figs. 3 and 4) (Lemon et al. 1990). The inoculum in this study (HM175/S18 virus) was a neutralization escape mutant with an aspartic acid to histidine substitution at residue 70 of the VP3 capsid protein (VP3-D70H mutation) that ablates binding of the neutralizing monoclonal antibody, K24F2 (Ping and Lemon 1992). Because the virus was adapted to growth in cell culture, it was possible to monitor fecal shedding and viremia by virus isolation. Infectious virus was recovered from feces as early as 4 days after intravenous inoculation. Fecal shedding of infectious virus peaked at ∼20 days postinoculation (coincident with the onset of serum ALT elevation and the first appearance of anti-HAV) at ∼107 RFU/gm of feces, then declined over the following 2 weeks (Fig. 3) (Lemon et al. 1990). Virus was also isolated from serum, but the titer of virus in serum was ∼100- to 1000-fold less than in feces. The period during which viremia was detectable extended for about 21 days, with serum titers generally peaking coincident with maximal ALT elevations. Both neutralizing antibody and infectious virus were present in serum from these animals during the early convalescence period, consistent with the protection afforded circulating virus by the quasi-envelope surrounding it. These results provide insight into virologic events in acute hepatitis A.

Figure 4.

Acute hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection in a New World owl monkey (Aotus trivirgatus). The animal was one of six infected by intravenous inoculation of a cell-culture-adapted virus permitting quantitation of infectious virus in feces and serum using a modified plaque assay method (Lemon et al. 1990). The challenge virus was a neutralization escape mutant with an amino acid substitution at residue 70 of VP3 that confers escape from a neutralizing monoclonal antibody; by day 12 of the infection, this virus was replaced with revertant virus with wild-type capsid sequence. Note that antibody and infectious virus cocirculated in blood for an extended period (see text for additional details). “RFU” = radioimmunofocus-forming unit.

Interestingly, although the VP3-D70H escape mutant replicated as well in cell culture as parental virus, it was rapidly replaced by revertant virus with wild-type capsid sequence in each of the six owl monkeys studied (Lemon et al. 1990). No clear explanation was apparent for the substantial replication advantage of wild-type virus over the VP3-D70H mutant in infected owl monkeys. However, the VP3 sequence of the AGM-27 virus recovered from an African green monkey has alanine rather than aspartic acid at VP3 residue 70, although VP3 is otherwise 97% identical in sequence to human HAV (Emerson et al. 1996). AGM-27 causes severe disease in African green monkeys and tamarins (S. mystax), but replicates poorly and is attenuated in chimpanzees. Taken together, these findings hint at the possibility that VP3 residue 70 may interact with a host species–specific cellular receptor.

As a positive-strand RNA virus, infectious HAV can be rescued from synthetic genome-length RNA following its transfection into permissive cell cultures (Cohen et al. 1987). This allows for reverse molecular genetics studies, a powerful approach to mapping the functions of viral genetic elements. Infectious HAV can also be recovered from NHPs following direct intrahepatic inoculation of RNA transcripts prepared from cloned complementary DNA (cDNA) (so-called “in vivo transfection”). This approach has been used in tamarins (S. mystax) to characterize the genetic basis of attenuation of HAV, and also to show that a lengthy polypyrimidine track present in the 5′ noncoding RNA of HAV is neither required for replication nor contributes to virulence in vivo (Funkhouser et al. 1994; Shaffer et al. 1995).

NHP Models and HAV Vaccine Development

Vaccines in common use today are comprised of formalin-inactivated virus produced in cell culture and adjuvanted with alum (Fiore et al. 2006). A proof-of-concept for inactivated vaccines was first shown by studies at the Merck Laboratories using virus purified from the liver of infected tamarins/marmosets (Provost and Hilleman 1978). Similar studies performed by the U.S. Army confirmed that a vaccine produced by formalin inactivation of cell-culture-derived virus was capable of protecting owl monkeys against challenge with wild-type virus (Binn et al. 1986). An important aspect of the NHP studies showed that antibodies from humans immunized with formalin-inactivated vaccine protected chimpanzees against virus challenge (Purcell et al. 1992). Although passive transfer of antibodies from vaccinated individuals prevented disease, it did not prevent infection. In contrast, immunization with the inactivated vaccine provided complete protection from infection (Purcell et al. 1992). These studies confirmed earlier research performed in humans over 80 years ago, which showed that the administration of pooled human immune globulin could prevent symptomatic hepatitis (Gellis et al. 1945). They established serum anti-HAV activity as a strong correlate of protective immunity, a finding borne out in subsequent human clinical trials of an inactivated HAV vaccine (Werzberger et al. 1992). Furthermore, they showed that sterilizing immunity is not necessary for protection from disease, a concept that would be important in the development of vaccines for other viruses. In this light, it is important to point out that HAV vaccine is protective against disease even when administered up to 2 weeks after exposure (see Shouval 2018). After extensive NHP safety studies, inactivated HAV vaccines produced by both SmithKline Beecham and Merck Laboratories were approved for use in the 1990s (Shouval et al. 1993). Thus, studies in NHPs provided data that contributed directly to the development of vaccines that have since protected millions of people from HAV infection.

Numerous other approaches to develop an HAV vaccine were attempted, including recombinant proteins, synthetic peptides, recombinant vaccinia, and poliovirus viruses and others. Most failed to provide sufficient protection in NHP trials. Although vaccinia was a promising experimental vaccine vector, widespread use in the human population would be problematic. Without NHP models, many of these vaccine attempts would have been tested in humans (D’Hondt 1992).

HEPATITIS E

Disease caused by HEV infection was originally described as “epidemic or enterically transmitted non-A non-B hepatitis” (ENANBH) to distinguish it from transfusion-associated non-A non-B hepatitis, now known as hepatitis C. The responsible virus is classified as a member of the Orthohepevirus genus in the Hepeviridae family. It is transmitted by the fecal–oral route primarily, and causes large outbreaks spread by contaminated water. An estimated two billion people have been exposed to HEV, almost exclusively in developing countries. There are four major HEV genotypes, each capable of infecting humans and with specific geographic associations: gt1 (Asia), gt2 (Africa and Mexico), gt3 (Europe and North America), and gt4 (Asia) (see Smith and Simmonds 2018). gt1 and gt2 are responsible for most HEV-related morbidity in humans, infecting an estimated 20 million persons per year and resulting in 3.3 million symptomatic infections and up to 44,000 deaths. Human infections with gt3 and gt4 primarily involve autochthonous infection in nonendemic regions, and are believed to be caused most often by consumption of undercooked swine or deer meat (Tei et al. 2003; Sonoda et al. 2004; Pavio et al. 2014). gt3 and gt4 infections are found in domestic pigs, wild boar, and deer, but HEV has also been detected in rabbits (Zhao et al. 2009) and rats (Kabrane-Lazizi et al. 1999). Although human infections are typically self-limited, gt3 and gt4 virus infections can persist in immunosuppressed individuals (Kamar et al. 2008) and lead to cirrhosis and liver failure (reviewed in Aggarwal and Jameel 2011).

The HEV genome is a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA approximately 7.2 kb in length with a 5′ 7-methylguanosine cap and a 3′ poly(A) tail, which are features that resemble endogenous cellular messenger RNAs. HEV RNA thus differs from HAV RNA, which has a VPg covalently linked to its 5′ terminus, a difference that may contribute to differences in the host response to infection. The HEV genome encodes three partially overlapping open reading frames (ORFs) (ORF1–3) (Tam et al. 1991; Ahmad et al. 2011). ORF1 encodes methyltransferase, protease, helicase, and RNA polymerase activities, whereas ORF2 encodes a capsid protein that exists in both glycosylated and nonglycosylated forms (Purdy et al. 1994; Jameel et al. 1996). ORF3 has been shown to bind to multiple cellular proteins and may play an essential role in virion egress from infected cells (Takahashi et al. 2010; reviewed in Ahmad et al. 2011). It is not essential for autonomous amplification of RNA replicons in culture (Emerson et al. 2006), but it is required for infection of macaques (Graff et al. 2006). HEV is excreted in feces as nonenveloped virions. However, similar to quasi-enveloped eHAV (Feng et al. 2013), HEV appears to circulate in the blood and be released from infected cell cultures in membranous vesicles (Takahashi et al. 2010; Qi et al. 2015; Yin et al. 2016). As with eHAV, the vesicle membranes surrounding the eHEV capsid may play a role in evading immune responses by protecting it from neutralizing antibody.

NHP Models of Hepatitis E

The first experimental primate infection with ENANBH occurred in a virologist who, in an effort to discover the cause of an outbreak of hepatitis among Soviet soldiers in Afghanistan, purposefully ingested a pool of fecal extracts. The volunteer became acutely ill and shed virus that was visualized in feces by immune electron microscopy (Balayan et al. 1983). The size of the particle and its buoyant density were defined. In the same study, virus was transmitted to cynomolgus monkeys (Balayan et al. 1983), fulfilling Koch’s postulates and confirming that the agent was capable of causing hepatitis both histologically and biochemically. Virus was detected in the feces of the infected cynomolgus monkeys, which developed antibody to the virus, thereby providing an NHP model for the study of ENANBH. Technology developed during the search for HCV was used to molecularly clone the HEV genome from virus present in the bile of experimentally infected macaques (Reyes et al. 1990; Tam et al. 1991). Nearly a decade would pass before an infectious clone was developed, in part because it was not appreciated that HEV produces a 5′ cap for both genomic and subgenomic RNAs. The first infectious molecular clone was validated by demonstrating infection following the inoculation of synthetic HEV RNA directly into the liver of a chimpanzee (Emerson et al. 2001). This study also confirmed that the 5′ cap, produced during infection by the methyltransferase present in the ORF1 protein product, is essential for infectivity of the virus.

Multiple NHP species can be infected by HEV, including cynomolgus and rhesus macaques (Tsarev et al. 1992, 1993), chimpanzees (McCaustland et al. 2000; Yu et al. 2010), and owl monkeys (Fig. 1) (Ticehurst et al. 1992). Other Old World and New World NHP species have been used for HEV studies, but less successfully, including pig-tailed macaques, African green monkeys, squirrel monkeys, and tamarins (Bradley et al. 1987; reviewed in Purcell and Emerson 2001). Pigs (Meng et al. 1997), rats (Kabrane-Lazizi et al. 1999; Johne et al. 2010), and rabbits (Zhao et al. 2009) are useful animal models for some genotypes and species-specific isolates.

The course of experimental HEV gt3 infection in a rhesus macaque is shown in Figure 5. The gt3 virus used for challenge was from a patient persistently coinfected with HEV and HIV (Dalton et al. 2009). Intravenous challenge with a high virus dose (approximately 107 genome equivalents) resulted in HEV fecal shedding for 2 weeks and transient viremia detected only at week 2 (Fig. 5). An IgM antibody response against the ORF2 capsid protein was detected at week 2 and subsided with the appearance of an IgG response. Very minimal serum ALT elevation of uncertain significance was noted at week 2 (Fig. 5). This study demonstrates that HEV gt3 infections can be quite mild in rhesus macaques. Purcell and colleagues have provided a detailed comparison of experimental HEV infection in cynomolgus and rhesus macaques and chimpanzees (Purcell et al. 2013). Reverse titration of an HEV gt1 isolate in these three NHP species revealed more significant hepatitis in the macaques than in the chimpanzees as measured by peak serum ALT values (Fig. 6A). Also, an inverse relationship was established between HEV gt1 challenge dose and the time to peak ALT elevation (Fig. 6B) and to serconversion in the rhesus monkeys. Interestingly, similar observations have been made with HAV in infected tamarins and Ifnar1−/− mice (Gust and Feinstone 1988; Hirai-Yuki et al. 2016). Finally, HEV gt1 and gt2 strains induced higher ALT elevations in rhesus monkeys than an HEV gt3 strain (Fig. 6C) (Purcell et al. 2013). Pigs, the natural host for gt3 virus, were also found to be more susceptible to gt3 infection when compared with nonhuman primates. Observations from this NHP study thus reinforce the prevailing view that inoculum size influences the course of liver disease and immunity in acute HEV infection, and that waterborne transmission of gt1 and gt2 viruses between humans is more likely to lead to clinically apparent liver disease than zoonotic transmission of gt3 viruses. The study by Purcell et al. (2013) also highlights the value of small NHPs like the rhesus macaque for studies of HEV infection and immunity.

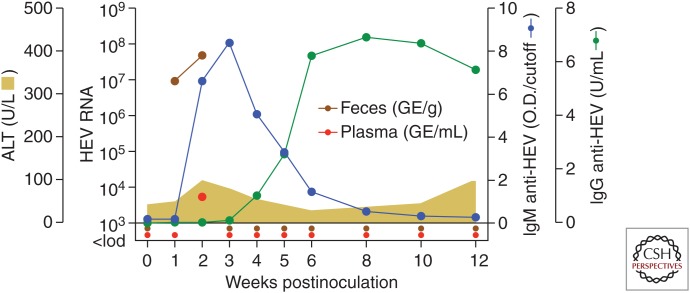

Figure 5.

Course of acute hepatitis E in a rhesus macaque. A rhesus macaque was challenged intravenously with 107 RNA genome equivalents of a hepatitis E virus (HEV) genotype gt3 strain designated Kernow (kindly provided by Dr. S. Emerson). HEV RNA genome titers in serum and feces were determined by RT-qPCR. Antibodies (IgM and IgG) against the HEV open reading frame 2 (ORF2) capsid were measured by ELISA assay.

Figure 6.

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection in macaque species and chimpanzees. (A) Peak ALT values in cynomolgus and rhesus macaques and chimpanzees infected with the same dose of a genotype (gt)1 HEV strain. Geometric mean peak ALT titers were significantly higher in both macaque species when compared with the chimpanzees. (B) The time to peak ALT was shorter in rhesus macaques infected with high versus low doses of an HEV gt1 strain. The study also established an inverse relationship between HEV challenge dose and the time to seroconversion (not shown). (C) Peak ALT values were significantly higher in rhesus macaques infected with gt1 and gt2 viruses when compared with a gt3 strain. (Adapted from Purcell et al. 2013.)

HEV Pathogenesis

Most studies performed in NHPs have used intravenous inoculation to initiate infection because (similar to HAV) the dose of virus is thousands-of-fold lower than what is required using the oral route. Virus is first detected in feces within the first week after infection and typically can be detected for 4 to 5 weeks. Detection in the serum is generally delayed by a few weeks. Serum ALT elevations typically occur within 3 to 4 weeks. Histological changes in the liver occur coincident with the appearance of an antibody response, suggesting the possibility that the pathology may be immune mediated. Histologic changes include ballooned hepatocytes, acidophilic bodies, focal parenchymal necrosis, and inflammatory infiltrates with enlarged portal tracks (see Cullen and Lemon 2018). These changes are accompanied by prominent accumulations of macrophages, activated Kupffer cells and a less striking presence of lymphocytes (reviewed in Krawczynski et al. 2011). A comparison of the course of infection in five cynomolgus macaques revealed two patterns of infection (Tsarev et al. 1993). Four animals experienced elevated serum ALT activities in the third and fourth weeks following infection, while a fourth animal had a biphasic pattern, with an initial increase in ALT activity at 26 days and a second at 54 days after infection. The first peak corresponded with histopathologic changes in the liver, while the second peak occurred at seroconversion. These observations raise questions as to the nature of the histopathology with regard to timing of the immune response, although sensitive assays for T-cell function were not available at the time of the study.

A poorly defined aspect of pathogenesis involves the high rate of acute liver failure observed in endemic regions in women infected with gt1 HEV during the later stages of pregnancy. Pregnant women are more likely to develop clinical disease in an epidemic setting compared to nonpregnant women and men. In addition, of the 17% to 20% of women who develop clinical disease when infected with gt1 HEV, up to 22% will develop fulminant hepatitis with a high mortality rate. Infection during pregnancy also results in a high rate of infection for the fetus with significant fetal mortality (reviewed in Aggarwal and Jameel 2011). In an attempt to understand the basis of this high mortality in pregnant females, six pregnant rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) in the first, second, and third trimesters of pregnancy, were inoculated intravenously with gt1 HEV. The study found no difference in the course of the infection in pregnant versus nonpregnant rhesus monkeys, and also failed to show transmission to the fetus (Tsarev et al. 1995). More recent studies in HEV-infected pregnant women with acute liver failure have compared the innate immune responses with women experiencing acute liver failure as a result of other causes (Sehgal et al. 2015). Macrophages were found to increase in number, but not in phagocytic function and generation of reactive oxygen species. Functional impairment of monocyte–macrophages in pregnant women with acute liver failure as a result of HEV was associated with reduced expression of Toll-like receptors (TLR3 and TLR7) and transcription factors regulating IFN expression (IRF3 and IRF7).

NHP Models and HEV Vaccine Development

Two HEV vaccine candidates have progressed to human clinical trials, based largely on preclinical studies in NHPs (reviewed extensively in Kamili 2011; also see Innis and Lynch 2018). In contrast to the experience with HAV, recombinant HEV capsid (ORF2) proteins have proven to be highly effective in inducing protective immunity. The ability to generate protective immunity in NHPs, primarily rhesus macaques, has been highly predictive of subsequent success in human clinical trials.

Bacterially Expressed ORF2 Vaccines

The first vaccine evaluated in NHPs contained the carboxyl two-thirds of the gt1 ORF2 protein product (amino acid residues 221–660) expressed in bacteria as a fusion protein (Purdy et al. 1993). The vaccine was examined in a small trial in cynomolgus monkeys and induced a strong antibody response. Two doses of vaccine failed to protect against hepatitis; three doses protected against hepatitis and infection (viremia) in one animal challenged with homologous virus, but did not prevent infection or hepatitis in an animal receiving a heterologous virus challenge.

Subsequent studies evaluated a vaccine consisting of a dimeric recombinant 23 kDa ORF2 peptide (pE2) from a gt1 Chinese strain of HEV produced in Escherichia coli (Im et al. 2001). Although highly immunogenic in rhesus macaques using potent Freund’s-based adjuvants (Im et al. 2001), immunogenicity was inadequate when formulated in alum, precluding further development. Extending the bacterial product by 23 amino acids (residues 368–606 of ORF2) yielded a protein that assembled into viral-like particles (Li et al. 2005; Zhu et al. 2010), and that when used in a vaccine protected rhesus macaques against both hepatitis and infection following challenge with homologous gt1 or heterologous gt4 viruses. This vaccine has been studied extensively in human clinical trials and was licensed as Hecolin in China in 2012 (Zhang et al. 2009; Zhu et al. 2010). More than 100,000 individuals were enrolled in a randomized, double-blind trial in a rural population in China with low endemic levels of gt1 and gt4 infections. Following three doses of vaccine, no cases of HEV were observed in the 48,693 monitored participants over 13 months following the last dose, while the placebo group of similar size experienced 15 cases. Analysis of a subset of subjects revealed 98.7% seroconversion in the immunized group and 2.1% seroconversion in the control group, suggesting HEV exposure in the control group during the follow-up period.

Baculovirus-Expressed ORF2 Immunogens

Yet another vaccine used as an immunogen a 56 kD protein derived from the gt1 Pakistani SAR55 virus ORF2 protein (Robinson et al. 1998). The 56 kD protein represents amino acids 112–607 of ORF2, and was expressed in insect cells using a baculovirus vector. It includes key neutralizing epitopes, and induced high levels of antibody. A single dose of this vaccine protected cynomolgus monkeys from both viremia and hepatitis, although some virus was detected in feces (Tsarev et al. 1994). In a larger study in rhesus macaques, two doses protected all animals from hepatitis following challenge with either homologous or heterologous virus (Tsarev et al. 1997). However, viremia and fecal shedding were detected in most animals. Interestingly, postexposure immunization provided no protection from hepatitis, a clear distinction from inactivated HAV vaccine. Additional studies showed that three of four rhesus macaques were protected against hepatitis when challenged intravenously with homologous virus 6 or 12 months after immunization (Zhang et al. 2002). In further preclinical trials, immunized rhesus macaques were challenged with three different HEV strains, including the homologous gt1 Pakistani SAR55 virus, the gt2 Mex-14 isolate, and gt3 US-2 virus. All 23 animals that had received two doses of the recombinant vaccine were protected from hepatitis based on the absence of elevated serum ALT activity, whereas six of eight control animals had increases in serum ALT (Purcell et al. 2003). Collectively, these extensive NHP studies provide evidence that protection from hepatic inflammation does not correlate directly with protection from HEV viremia or fecal shedding, and suggest that sterilizing immunity may not be a realistic goal for prevention of hepatitis E. It should be appreciated, however, that these studies involved challenge with a high dose of virus inoculated intravenously. This is a much more stringent test of immunity than what would be expected in natural infection: a low-dose oral exposure, albeit possibly repetitively when water supplies are contaminated. In a subsequent randomized human clinical trial, the vaccine showed 95% efficacy in military troops in Nepal (Shrestha et al. 2007).

A similar baculovirus-derived vaccine was developed using a Burmese strain of HEV. Immunization with a 62 kD protein purified from insect cells protected two of three cynomolgus macaques from developing hepatitis or detectable evidence of infection when challenged with virus (Yarbough 1999). This vaccine candidate was not evaluated further.

DNA Vaccines

A DNA vaccine would be highly cost effective in comparison to recombinant HEV protein–based vaccines, and has also been evaluated in NHPs. In a small study in cynomolgus macaques, DNA encoding the full-length ORF2 protein of a Burmese HEV strain was delivered by a biolistic particle delivery system (“gene gun”). Following four doses of the vaccine, animals were challenged with a heterologous Mexican HEV strain. The animals were protected against both hepatitis and infection as determined by detection of viral RNA in serum or feces (Kamili et al. 2004). Intradermal vaccination with DNA failed to provide protection. Yet another vaccine encoding ORF2 residues 458–602 was administered to macaques using a liposome-encapsulated DNA prime-protein boost strategy, and found to provide protection against both disease and infection with HEV (Arankalle et al. 2009). Thus, although commercially produced HEV vaccines are not generally available outside of China, a very large body of work in NHPs has shown the feasibility of successful immunization with a variety of immunogens.

COMPARISON OF HEV AND HAV INFECTIONS IN CHIMPANZEES

Although studies to directly compare HEV and HAV infections in chimpanzees have not been conducted, two studies have been performed in which infection with HCV was compared either to HEV or HAV in chimpanzees. These studies are of particular value, because both used total genome microarray analysis and serial liver tissue samples to evaluate viral–host interactions, including innate and adaptive immune responses.

Contrasts between HEV and HCV Infections

In studies comparing HEV with HCV infection in chimpanzees (Yu et al. 2010), both viruses could be detected in the blood and liver within 2 weeks of intravenous inoculation. The duration of viremia was prolonged following HCV infection, with virus detectable intermittently for 20 to 25 weeks, although peak levels declined by 10 weeks after infection. In contrast, viremia in HEV-infected chimpanzees persisted for only 5 weeks. In general, viral RNA in the liver paralleled the detection of viremia in both infections. Serum ALT activity peaked 10 to 15 weeks after inoculation of HCV, whereas peak ALT elevations occurred within 5 weeks of HEV infection. The peak ALT activity was threefold higher in HCV infections compared to HEV infections.

Microarray analysis revealed that both viral infections induced an early innate immune response exemplified by increases in transcripts for multiple IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs). The number of genes with increased levels of expression, as well as the magnitude of the increase, was much greater following HCV infection in comparison to HEV infection. The robust ISG expression observed following HCV infection is consistent with several previous microarray studies in acute and chronically HCV-infected chimpanzees (Bigger et al. 2001, 2004; Su et al. 2002; Lanford et al. 2007). Genes induced early in acute HCV infection correlated well with ISGs induced by injection of chimpanzees with IFN-α (Lanford et al. 2006). A detailed discussion of the genes induced by these viruses is beyond the scope of this review. However, in addition to a greater magnitude of ISG induction, ISGs remained induced for longer periods of time in HCV-infected chimpanzees.

Contrasts between HAV and HCV Infections

In a separate study, acute HAV infection was compared with acute resolving HCV infection in chimpanzees infected intravenously with either virus (Lanford et al. 2011a). Several aspects of this study were novel and worth noting. First, peak ALT levels were much greater in HAV-infected than HCV-infected chimpanzees. This is in contrast to HEV infection, where ALT levels were lower than in HCV-infected chimpanzees (Yu et al. 2010). In HAV-infected animals, peak ALT elevations were associated with massive portal mononuclear cell infiltrates that extended into the parenchyma at weeks 3 and 4 (Fig. 2A). The inflammatory infiltrate was associated with severe hepatocyte swelling and necrosis. At week 4, up to 40% of cells in selected fields stained positively for activated caspase 3, a marker of apoptosis. Ki67, a marker of cell proliferation, was expressed by numerous hepatocytes at weeks 3–4, indicative of liver regeneration because of extensive cell death. Potentially relevant to this, HAV genome copy numbers in the liver were 100-fold greater than the number of HCV genomes in acute HCV infection, although the magnitudes of HAV and HCV viremia were comparable. Remarkably, although HAV viremia and fecal virus shedding declined dramatically, coincident with elevations in serum ALT, intrahepatic genome copy numbers declined very slowly, with viral RNA persisting at readily detectable levels for many months (Fig. 3). This persistence of HAV RNA contrasted sharply with HCV RNA persistence following resolution of acute HCV infection; intrahepatic HCV RNA declined in parallel with viremia and was typically no longer detectable 10–20 weeks after infection. It also contrasts with HEV infection, in which intrahepatic viral RNA typically became undetectable within 5 weeks (Yu et al. 2010).

The most striking difference between HAV and HCV infections, however, was in the induction of the innate immune response (Table 1). As described above, HCV induces a robust intrahepatic ISG response. High levels of ISG15 protein could be detected by immunohistochemical staining in nearly every hepatocyte during acute HCV infection (Lanford et al. 2011a), whereas genes related to B- and T-cell responses were not highly induced during viral clearance. In contrast, the ISG response was extraordinarily muted in acute HAV infection, with only low-level induction of a few ISGs in the first 2 weeks after infection that subsequently subsided despite high and increasing levels of viral RNA in the liver (Lanford et al. 2011a). This correlated with the transient presence of plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) in hepatic sinusoids during the first 2 weeks of HAV infection (Feng et al. 2015). These cells are extraordinarily efficient producers of type I IFNs. In vitro studies suggest pDCs respond preferentially to quasi-enveloped eHAV, which is the only form of virus detectable in plasma or serum from acutely infected chimpanzees (Feng et al. 2013, 2015). For unclear reasons, pDCs were no longer detectable in the liver 3 and 4 weeks after infection, after ISG expression has declined and before peak levels of intrahepatic viral RNA and serum ALT activities (Feng et al. 2015). A few ISGs remained elevated throughout the acute phase of HAV infection, but these were ISGs that are positively regulated by IFN-γ (e.g., TAP1 and STAT1). The lack of a strong type I IFN response in HAV infection is likely because of the ability of HAV-encoded proteases to degrade human MAVS, TRIF, and NEMO, key host proteins involved in the induction of IFN responses to virus infection (Yang et al. 2007; Qu et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2014; Lemon et al. 2017), thus leading to a highly stealthy invasion of the liver (Lanford et al. 2011a; see Feng and Lemon 2018).

Table 1.

Analysis of gene expression in acute HAV and HCV infections

| Weeks postinfection | HAV acute infection | HCV acute infection | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAV 1 | HCV 1 | HCV 2 | ||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 10 | 14 | 26 | 4 | 22 | 4 | 12 | |

| Gene symbols | ||||||||||||

| Interferon signaling | ||||||||||||

| IFIT3 | 4 | 3 | 32 | 23 | 8 | 4 | ||||||

| IFIT1 | 4 | 21 | 19 | 11 | 6 | |||||||

| OAS1 | 17 | 13 | 5 | 4 | ||||||||

| MX1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 20 | 13 | 6 | 6 | |||||

| STAT1 | 4 | 10 | 11 | 3 | 3 | 18 | 10 | 3 | 4 | |||

| TAP1 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | |||||||

| B-cell development | ||||||||||||

| IGL@ | 127 | 93 | 50 | |||||||||

| IGK@ | 25 | 33 | 35 | 32 | 21 | 25 | ||||||

| IGHM | 32 | 16 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 3 | ||||||

| HLA-DQB1 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 3 | ||||||||

| HLA-DRB1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | |||||||||

| HLA-DQA1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | ||||||||

| CTL-mediated apoptosis | ||||||||||||

| CD3G | 21 | |||||||||||

| GZMB | 17 | 15 | ||||||||||

| PRF1 | 5 | 6 | ||||||||||

| CD3D | 3 | |||||||||||

| FCER1G | 2 | 3 | ||||||||||

| Natural killer cell signaling | ||||||||||||

| LCK | 5 | 7 | 5 | |||||||||

| RAC2 | 4 | 5 | 3 | |||||||||

| KLRC2///KLRC1 | 3 | 4 | ||||||||||

| SYK | 3 | 3 | ||||||||||

| FCER1G | 2 | 3 | ||||||||||

| LCP2 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||||

Data in table adapted from Lanford et al. (2011a).

The decline of HAV viremia at weeks 3–4 coincided with the appearance of serum antibodies (Fig. 3) and with massive increases in hepatic expression of genes associated with B-cell development (Table 1). This evidence of B-cell activation correlates well with the striking presence of numerous plasma cells among cell types infiltrating the acutely inflamed HAV-infected liver, which is a unique feature of the pathology of HAV infection not seen in other viral hepatidites (see Cullen and Lemon 2018).

Another unique finding to emerge from this study came from an extensive analysis of the T-cell response of the HAV-infected animals (Zhou et al. 2012; see Wedemeyer 2018). Control of the infection was attributed predominantly to a multifunctional CD4+ T-cell response, rather than to CD8+ T cells as previously suggested. HAV-specific CD8+ T cells were either not detected in the blood or failed to display effector function until after viremia and hepatitis began to subside. In contrast, CD4+ T cells producing multiple cytokines (interleukin [IL]2, IL21, IFN-γ, and tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-α) were detected when viremia first declined. In addition, only CD4+ T cells responded during a transient resurgence of fecal HAV shedding (Fig. 1). This helper response then contracted slowly over several months as HAV genomes were cleared from the liver. These findings indicate a dominant role for CD4+ T cells in the termination of HAV infection. The results suggest a novel paradigm for cytokine-mediated CD4+ T-cell control of HAV infection that is distinct from earlier concepts of a primary role for cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell immunity (Walker et al. 2015). However, B-cell responses, which dominate host transcriptional changes in the acutely HAV-infected liver (Lanford et al. 2011a), and antibody are key to immunity against reinfection and are also likely to contribute to clearance of the infection.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Our current knowledge of HAV and HEV infections rests heavily on historical studies of these infections conducted in NHPs, some of which were performed decades ago, before the development of numerous technologies considered routine today. The most relevant of these studies were conducted in chimpanzees. As described above, almost two decades after the licensing of an HAV vaccine, the chimpanzee model of hepatitis A was revisited using state-of-the-art technologies in a remarkable study that revealed many unexpected findings (Lanford et al. 2011a; Feng et al. 2013). These chimpanzees were very likely to be the last to be infected experimentally with a human hepatitis virus, as the use chimpanzees in invasive biomedical research is now highly restricted. Nonetheless, the results of this study point clearly as to how much still needs to be learned with regard to viral–host interactions in HAV, as well as HEV, infections. Fortunately, unlike HBV and HCV, several other NHP species are permissive for HAV and HEV and accurately recapitulate many aspects of infection in humans.

Vaccines have been developed for both HAV and HEV based largely on the results of preclinical studies in NHPs. However, both viruses still pose considerable health care burdens that warrant continued research to better understand viral–host interactions and to develop effective interventions, especially for HEV. New models using mice and novel culture systems are rapidly being developed to explore various aspects of viral–host interactions, but confirmation or validation of significant new findings will likely require the use of NHPs, especially if intended for development of human therapeutics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Helen Hawn for excellent editorial assistance with this review.

Footnotes

Editors: Stanley M. Lemon and Christopher Walker

Additional Perspectives on Enteric Hepatitis Viruses available at www.perspectivesinmedicine.org

REFERENCES

*Reference is also in this collection.

- Aggarwal R, Jameel S. 2011. Hepatitis E. Hepatology 54: 2218–2226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad I, Holla RP, Jameel S. 2011. Molecular virology of hepatitis E virus. Virus Res 161: 47–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altevogt BM, Pankevich DE, Shelton-Davenport MK, Kahn JP, eds. 2011. Chimpanzees in biomedical and behavioral research: Assessing the necessity. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amado LA, Marchevsky RS, de Paula VS, Hooper C, Freire MS, Gaspar AM, Pinto MA. 2010. Experimental hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection in cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis): Evidence of active extrahepatic site of HAV replication. Int J Exp Pathol 91: 87–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arankalle VA, Ramakrishnan J. 2009. Simian hepatitis A virus derived from a captive rhesus monkey in India is similar to the strain isolated from wild African green monkeys in Kenya. J Viral Hepat 16: 214–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arankalle VA, Lole KS, Deshmukh TM, Srivastava S, Shaligram US. 2009. Challenge studies in Rhesus monkeys immunized with candidate hepatitis E vaccines: DNA, DNA-prime-protein-boost and DNA-protein encapsulated in liposomes. Vaccine 27: 1032–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asher LV, Binn LN, Mensing TL, Marchwicki RH, Vassell RA, Young GD. 1995. Pathogenesis of hepatitis A in orally inoculated owl monkeys (Aotus trivirgatus). J Med Virol 47: 260–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balayan MS, Andjaparidze AG, Savinskaya SS, Ketiladze ES, Braginsky DM, Savinov AP, Poleschuk VF. 1983. Evidence for a virus in non-A, non-B hepatitis transmitted via the fecal–oral route. Intervirology 20: 23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bancroft WH, Snitbhan R, Scott RM, Tingpalapong M, Watson WT, Tanticharoenyos P, Karwacki JJ, Srimarut S. 1977. Transmission of hepatitis B virus to gibbons by exposure to human saliva containing hepatitis B surface antigen. J Infect Dis 135: 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigger CB, Brasky KM, Lanford RE. 2001. DNA microarray analysis of chimpanzee liver during acute resolving hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol 75: 7059–7066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigger CB, Guerra B, Brasky KM, Hubbard G, Beard MR, Luxon BA, Lemon SM, Lanford RE. 2004. Intrahepatic gene expression during chronic hepatitis C virus infection in chimpanzees. J Virol 78: 13779–13792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binn LN, Lemon SM. 2010. Hepatitis A. In Vaccines, a biography (ed. Artenstein, AW), pp. 335–346. Springer, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Binn LN, Lemon SM, Marchwicki RH, Redfield RR, Gates NL, Bancroft WH. 1984. Primary isolation and serial passage of hepatitis A virus strains in primate cell cultures. J Clin Microbiol 20: 28–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binn LN, Bancroft WH, Lemon SM, Marchwicki RH, LeDuc JW, Trahan CJ, Staley EC, Keenan CM. 1986. Preparation of a prototype inactivated hepatitis A virus vaccine from infected cell cultures. J Infect Dis 153: 749–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boggs JD, Melnick JL, Conrad ME, Felsher BF. 1970. Viral hepatitis. Clinical and tissue culture studies. JAMA 214: 1041–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley DW, Krawczynski K, Cook EH Jr, McCaustland KA, Humphrey CD, Spelbring JE, Myint H, Maynard JE. 1987. Enterically transmitted non-A, non-B hepatitis: Serial passage of disease in cynomolgus macaques and tamarins and recovery of disease-associated 27- to 34-nm viruslike particles. Proc Natl Acad Sci 84: 6277–6281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JI, Ticehurst JR, Feinstone SM, Rosenblum B, Purcell RH. 1987. Hepatitis A virus cDNA and its RNA transcripts are infectious in cell culture. J Virol 61: 3035–3039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JI, Feinstone S, Purcell RH. 1989. Hepatitis A virus infection in a chimpanzee: Duration of viremia and detection of virus in saliva and throat swabs. J Infect Dis 160: 887–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Cullen JM, Lemon SM. 2018. Comparative pathology of hepatitis A virus and hepatitis E virus infection. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 10.1101/cshperspect.a033456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Daemer RJ, Feinstone SM, Gust ID, Purcell RH. 1981. Propagation of human hepatitis A virus in African green monkey kidney cell culture: Primary isolation and serial passage. Infect Immun 32: 388–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton HR, Bendall RP, Keane FE, Tedder RS, Ijaz S. 2009. Persistent carriage of hepatitis E virus in patients with HIV infection. N Engl J Med 361: 1025–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deinhardt F, Deinhardt JB. 1984. Animal models. In Hepatitis A (ed. Gerety, RJ), pp. 185–204. Academic, Orlando, FL. [Google Scholar]

- Deinhardt F, Holmes AW, Capps RB, Popper H. 1967. Studies on the transmission of human viral hepatitis to marmoset monkeys. I: Transmission of disease, serial passages, and description of liver lesions. J Exp Med 125: 673–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Hondt E. 1992. Possible approaches to develop vaccines against hepatitis A. Vaccine 10: S48–S52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dienstag JL, Feinstone SM, Purcell RH, Hoofnagle JH, Barker LF, London WT, Popper H, Peterson JM, Kapikian AZ. 1975. Experimental infection of chimpanzees with hepatitis A virus. J Infect Dis 132: 532–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dienstag JL, Davenport FM, McCollum RW, Hennessy AV, Klatskin G, Purcell RH. 1976a. Nonhuman primate-associated viral hepatitis type A. Serologic evidence of hepatitis A virus infection. JAMA 236: 462–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dienstag JL, Popper H, Purcell RH. 1976b. The pathology of viral hepatitis types A and B in chimpanzees. A comparison. Am J Pathol 85: 131–148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drexler JF, Corman VM, Lukashev AN, van den Brand JM, Gmyl AP, Brunink S, Rasche A, Seggewibeta N, Feng H, Leijten LM, et al. 2015. Evolutionary origins of hepatitis A virus in small mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci 112: 15190–15195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenfeld E, Domingo E, Roos R., eds. 2010. The Picornaviruses. ASM, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson SU, Tsarev SA, Govindarajan S, Shapiro M, Purcell RH. 1996. A simian strain of hepatitis A virus, AGM-27, functions as an attenuated vaccine for chimpanzees. J Infect Dis 173: 592–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson SU, Zhang M, Meng XJ, Nguyen H, St Claire M, Govindarajan S, Huang YK, Purcell RH. 2001. Recombinant hepatitis E virus genomes infectious for primates: Importance of capping and discovery of a cis-reactive element. Proc Natl Acad Sci 98: 15270–15275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson SU, Clemente-Casares P, Moiduddin N, Arankalle VA, Torian U, Purcell RH. 2006. Putative neutralization epitopes and broad cross-genotype neutralization of Hepatitis E virus confirmed by a quantitative cell-culture assay. J Gen Virol 87: 697–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Feinstone SM. 2018. History of the discovery of hepatitis A virus. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 10.1101/cshperspect.a031740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Feinstone SM, Kapikian AZ, Purcell RH. 1973. Hepatitis A: Detection by immune electron microscopy of a viruslike antigen associated with acute illness. Science 182: 1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstone SM, Daemer RJ, Gust ID, Purcell RH. 1983. Live attenuated vaccine for hepatitis A. Dev Biol Stand 54: 429–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Feng Z, Lemon SM. 2018. Innate immunity to enteric hepatitis viruses. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 10.1101/cshperspect.a033464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Feng Z, Hensley L, McKnight KL, Hu F, Madden V, Ping L, Jeong SH, Walker C, Lanford RE, Lemon SM. 2013. A pathogenic picornavirus acquires an envelope by hijacking cellular membranes. Nature 496: 367–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z, Hirai-Yuki A, McKnight KL, Lemon SM. 2014. Naked viruses that aren’t always naked: Quasi-enveloped agents of acute hepatitis. Annu Rev Virol 1: 539–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z, Li Y, McKnight KL, Hensley L, Lanford RE, Walker CM, Lemon SM. 2015. Human pDCs preferentially sense enveloped hepatitis A virions. J Clin Invest 125: 169–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore AE, Wasley A, Bell BP. 2006. Prevention of hepatitis A through active or passive immunization: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 55: 1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funkhouser AW, Purcell RH, D’Hondt E, Emerson SU. 1994. Attenuated hepatitis A virus: Genetic determinants of adaptation to growth in MRC-5 cells. J Virol 68: 148–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellis SS, Stokes J Jr, Forster H Jr, Brother GM, Hall WM. 1945. The use of human immune serum globulin (γ globulin): In infectious (epidemic) hepatitis in the mediterranean theater of operations ii. Studies on treatment in an epidemic of infectious hepatitis. JAMA 128: 1158–1159. [Google Scholar]

- Graff J, Torian U, Nguyen H, Emerson SU. 2006. A bicistronic subgenomic mRNA encodes both the ORF2 and ORF3 proteins of hepatitis E virus. J Virol 80: 5919–5926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gust ID, Feinstone SM. 1988. Hepatitis A. CRC, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- Havens WP. 1946. Period of infectivity of patients with experimentally induced infectious hepatitis. J Exp Med 83: 251–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai-Yuki A, Hensley L, McGivern DR, Gonzalez-Lopez O, Das A, Feng H, Sun L, Wilson JE, Hu F, Feng Z, et al. 2016. MAVS-dependent host species range and pathogenicity of human hepatitis A virus. Science 353: 1541–1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Hirai-Yuki A, Whitmire JK, Joyce M, Tyrrell DL, Lemon SM. 2018. Murine models of hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 10.1101/cshperspect.a031674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Holmes AW, Wolfe L, Rosenblate H, Deinhardt F. 1969. Hepatitis in marmosets: Induction of disease with coded specimens from a human volunteer study. Science 165: 816–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im SW, Zhang JZ, Zhuang H, Che XY, Zhu WF, Xu GM, Li K, Xia NS, Ng MH. 2001. A bacterially expressed peptide prevents experimental infection of primates by the hepatitis E virus. Vaccine 19: 3726–3732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Innis BL, Lynch JA. 2018. Immunization against hepatitis E. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 10.1101/cshperspect.a032573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- *.Jacobsen KH. 2018. Globalization and the changing epidemiology of hepatitis A virus (HAV). Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 10.1101/cshperspect.a031716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jameel S, Zafrullah M, Ozdener MH, Panda SK. 1996. Expression in animal cells and characterization of the hepatitis E virus structural proteins. J Virol 70: 207–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen RW, Newbold JE, Lemon SM. 1988. Complete nucleotide sequence of a cell culture-adapted variant of hepatitis A virus: Comparison with wild-type virus with restricted capacity for in vitro replication. Virology 163: 299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johne R, Plenge-Bonig A, Hess M, Ulrich RG, Reetz J, Schielke A. 2010. Detection of a novel hepatitis E-like virus in faeces of wild rats using a nested broad-spectrum RT-PCR. J Gen Virol 91: 750–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabrane-Lazizi Y, Fine JB, Elm J, Glass GE, Higa H, Diwan A, Gibbs CJ Jr, Meng XJ, Emerson SU, Purcell RH. 1999. Evidence for widespread infection of wild rats with hepatitis E virus in the United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg 61: 331–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamar N, Guitard J, Ribes D, Esposito L, Rostaing L. 2008. A monocentric observational study of darbepoetin alfa in anemic hepatitis-C-virus transplant patients treated with ribavirin. Exp Clin Transplant 6: 271–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamili S. 2011. Toward the development of a hepatitis E vaccine. Virus Res 161: 93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamili S, Spelbring J, Carson D, Krawczynski K. 2004. Protective efficacy of hepatitis E virus DNA vaccine administered by gene gun in the cynomolgus macaque model of infection. J Infect Dis 189: 258–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karron RA, Daemer R, Ticehurst J, D’Hondt E, Popper H, Mihalik K, Phillips J, Feinstone S, Purcell RH. 1988. Studies of prototype live hepatitis A virus vaccines in primate models. J Infect Dis 157: 338–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedda MA, Kramvis A, Kew MC, Lecatsas G, Paterson AC, Aspinall S, Stark JH, De Klerk WA, Gridelli B. 2000. Susceptibility of chacma baboons (Papio ursinus orientalis) to infection by hepatitis B virus. Transplantation 69: 1429–1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan CM, Lemon SM, LeDuc JW, McNamee GA, Binn LN. 1984. Pathology of hepatitis A infection in the owl monkey (Aotus trivirgatus). Am J Pathol 115: 1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczynski K, Meng XJ, Rybczynska J. 2011. Pathogenetic elements of hepatitis E and animal models of HEV infection. Virus Res 161: 78–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krugman S, Ward R, Giles JP, Bodansky O, Jacobs AM. 1959. Infectious hepatitis: Detection of virus during the incubation period and in clinically inapparent infection. N Engl J Med 261: 729–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanford RE, Guerra B, Lee H, Chavez D, Brasky K, Bigger CB. 2006. Genomic response to interferon-α in chimpanzees: Implications of rapid downregulation for hepatitis C kinetics. Hepatology 43: 961–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanford RE, Guerra B, Bigger CB, Lee H, Chavez D, Brasky KM. 2007. Lack of response to exogenous interferon-α in the liver of chimpanzees chronically infected with hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 46: 999–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanford RE, Feng Z, Chavez D, Guerra B, Brasky KM, Zhou Y, Yamane D, Perelson AS, Walker CM, Lemon SM. 2011a. Acute hepatitis A virus infection is associated with a limited type I interferon response and persistence of intrahepatic viral RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108: 11223–11228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanford RE, Lemon SM, Walker C. 2011b. The chimpanzee model of hepatitis C infections and small animal surrogates. In Hepatitis C antiviral drug discovery and development (ed. He Y, Tan T), pp. 99–132. Horizons Scientific, Norwich, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Lemon SM. 1985. Type A viral hepatitis: New developments in an old disease. N Engl J Med 313: 1059–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemon SM, LeDuc JW, Binn LN, Escajadillo A, Ishak KG. 1982. Transmission of hepatitis A virus among recently captured Panamanian owl monkeys. J Med Virol 10: 25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemon SM, Binn LN, Marchwicki R, Murphy PC, Ping LH, Jansen RW, Asher LVS, Stapleton JT, Taylor DG, LeDuc JW. 1990. In vivo replication and reversion to wild-type of a neutralization-resistant variant of hepatitis A virus. J Infect Dis 161: 7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemon SM, Murphy PC, Shields PA, Ping LH, Feinstone SM, Cromeans T, Jansen RW. 1991. Antigenic and genetic variation in cytopathic hepatitis A virus variants arising during persistent infection: Evidence for genetic recombination. J Virol 65: 2056–2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemon SM, Ott JJ, Van Damme P, Shouval D. 2017. Type A viral hepatitis: A summary and update on the molecular virology, epidemiology, pathogenesis and prevention. J Hepatol 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SW, Zhang J, Li YM, Ou SH, Huang GY, He ZQ, Ge SX, Xian YL, Pang SQ, Ng MH, et al. 2005. A bacterially expressed particulate hepatitis E vaccine: Antigenicity, immunogenicity and protectivity on primates. Vaccine 23: 2893–2901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao JS, Dong DX, Zhang SY, Zhang HY, Chen NL, Huang HY, Xie RY, Chai CA, Zhou TJ, Wu DM, et al. 1991. Further studies of attenuated live hepatitis A vaccine (H2 strain) in humans. In Viral Hepatitis and Liver Disease, pp. 110–111. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Mathiesen LR, Drucker J, Lorenz D, Wagner JA, Gerety RJ, Purcell RH. 1978. Localization of hepatitis A antigen in marmoset organs during acute infection with hepatitis A virus. J Infect Dis 138: 369–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathiesen LR, Moller AM, Purcell RH, London WT, Feinstone SM. 1980. Hepatitis A virus in the liver and intestine of marmosets after oral inoculation. Infect Immun 28: 45–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard JE, Bradley DW, Gravelle CR, Ebert JW, Krushak DH. 1975a. Preliminary studies of hepatitis A in chimpanzees. J Infect Dis 131: 194–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard JE, Krushak DH, Bradley DW, Berquist KR. 1975b. Infectivity studies of hepatitis A and B in non-human primates. Dev Biol Stand 30: 229–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaustland KA, Krawczynski K, Ebert JW, Balayan MS, Andjaparidze AG, Spelbring JE, Cook EH, Humphrey C, Yarbough PO, Favorov MO, et al. 2000. Hepatitis E virus infection in chimpanzees: A retrospective analysis. Arch Virol 145: 1909–1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng XJ, Purcell RH, Halbur PG, Lehman JR, Webb DM, Tsareva TS, Haynes JS, Thacker BJ, Emerson SU. 1997. A novel virus in swine is closely related to the human hepatitis E virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci 94: 9860–9865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midthun K, Ellerbeck E, Gershman K, Calandra G, Krah D, McCaughtry M, Nalin D, Provost P. 1991. Safety and immunogenicity of a live attenuated hepatitis A virus vaccine in seronegative volunteers. J Infect Dis 163: 735–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavio N, Merbah T, Thebault A. 2014. Frequent hepatitis E virus contamination in food containing raw pork liver, France. Emerg Infect Dis 20: 1925–1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ping LH, Lemon SM. 1992. Antigenic structure of human hepatitis A virus defined by analysis of escape mutants selected against murine monoclonal antibodies. J Virol 66: 2208–2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provost PJ, Hilleman MR. 1978. An inactivated hepatitis A virus vaccine prepared from infected marmoset liver. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 159: 201–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provost PJ, Hilleman MR. 1979. Propagation of human hepatitis A virus in cell culture in vitro. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 160: 213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provost PJ, Conti PA, Giesa PA, Banker FS, Buynak EB, McAleer WJ, Hilleman MR. 1983. Studies in chimpanzees of live, attenuated hepatitis A vaccine candidates. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 172: 357–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell RH, Emerson SU. 2001. Animal models of hepatitis A and E. ILAR J 42: 161–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell RH, D’Hondt E, Bradbury R, Emerson SU, Govindarajan S, Binn L. 1992. Inactivated hepatitis A vaccine: Active and passive immunoprophylaxis in chimpanzees. Vaccine 10: S148–S151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell RH, Wong DC, Shapiro M. 2002. Relative infectivity of hepatitis A virus by the oral and intravenous routes in 2 species of nonhuman primates. J Infect Dis 185: 1668–1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell RH, Nguyen H, Shapiro M, Engle RE, Govindarajan S, Blackwelder WC, Wong DC, Prieels JP, Emerson SU. 2003. Pre-clinical immunogenicity and efficacy trial of a recombinant hepatitis E vaccine. Vaccine 21: 2607–2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell RH, Engle RE, Govindarajan S, Herbert R, St Claire M, Elkins WR, Cook A, Shaver C, Beauregard M, Swerczek J, et al. 2013. Pathobiology of hepatitis E: Lessons learned from primate models. Emerg Microbes Infect 2: e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdy MA, McCaustland KA, Krawczynski K, Spelbring J, Reyes GR, Bradley DW. 1993. Preliminary evidence that a trpE-HEV fusion protein protects cynomolgus macaques against challenge with wild-type hepatitis E virus (HEV). J Med Virol 41: 90–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdy MA, Carson D, McCaustland KA, Bradley DW, Beach MJ, Krawczynski K. 1994. Viral specificity of hepatitis E virus antigens identified by fluorescent antibody assay using recombinant HEV proteins. J Med Virol 44: 212–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Y, Zhang F, Zhang L, Harrison TJ, Huang W, Zhao C, Kong W, Jiang C, Wang Y. 2015. Hepatitis E virus produced from cell culture has a lipid envelope. PLoS ONE 10: e0132503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu L, Feng Z, Yamane D, Liang Y, Lanford RE, Li K, Lemon SM. 2011. Disruption of TLR3 signaling due to cleavage of TRIF by the hepatitis A virus protease-polymerase processing intermediate, 3CD. PLoS Pathog 7: e1002169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes GR, Purdy MA, Kim JP, Luk KC, Young LM, Fry KE, Bradley DW. 1990. Isolation of a cDNA from the virus responsible for enterically transmitted non-A, non-B hepatitis. Science 247: 1335–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson RA, Burgess WH, Emerson SU, Leibowitz RS, Sosnovtseva SA, Tsarev S, Purcell RH. 1998. Structural characterization of recombinant hepatitis E virus ORF2 proteins in baculovirus-infected insect cells. Protein Expr Purif 12: 75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum LS, Villarino ME, Nainan OV, Melish ME, Hadler SC, Pinsky PP, Jarvis WR, Ott CE, Margolis HS. 1991. Hepatitis A outbreak in a neonatal intensive care unit: Risk factors for transmission and evidence of prolonged viral excretion among preterm infants. J Infect Dis 164: 476–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffner F, Dienstag JL, Purcell RH, Popper H. 1977. Chimpanzee livers after infection with human hepatitis viruses A and B: Ultrastructural studies. Arch Pathol Lab Med 101: 113–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulman AN, Dienstag JL, Jackson DR, Hoofnagle JH, Gerety RJ, Purcell RH, Barker LF. 1976. Hepatitis A antigen particles in liver, bile, and stool of chimpanzees. J Infect Dis 134: 80–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehgal R, Patra S, David P, Vyas A, Khanam A, Hissar S, Gupta E, Kumar G, Kottilil S, Maiwall R, et al. 2015. Impaired monocyte-macrophage functions and defective Toll-like receptor signaling in hepatitis E virus-infected pregnant women with acute liver failure. Hepatology 62: 1683–1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer DR, Emerson SU, Murphy PC, Govindarajan S, Lemon SM. 1995. A hepatitis A virus deletion mutant which lacks the first pyrimidine-rich tract of the 5′ nontranslated RNA remains virulent in primates after direct intrahepatic nucleic acid transfection. J Virol 69: 6600–6604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevtsova ZV, Lapin BA, Doroshenko NV, Krilova RI, Korzaja LI, Lomovskaya IB, Dzhelieva ZN, Zairov GK, Stakhanova VM, Belova EG, et al. 1988. Spontaneous and experimental hepatitis A in Old World monkeys. J Med Primatol 17: 177–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu YK, Mathiesen LR, Lorenz D, Drucker J, Feinstone SM, Wagner JA, Purcell RH. 1978. Localization of hepatitis A antigen in liver tissue by peroxidase-conjugated antibody method: Light and electron microscopic studies. J Immunol 121: 1671–1679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Shin E-C, Jeong S-H. 2018. Natural history, clinical manifestations, and pathogenesis of hepatitis A. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 10.1101/cshperspect.a031708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- *.Shouval D. 2018. Immunization against hepatitis A. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 10.1101/cshperspect.a031682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Shouval D, Ashur Y, Adler R, Lewis JA, Miller W, Kuter B, Brown L, Nalin DR. 1993. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of an inactivated hepatitis A vaccine: Effects of single and booster injections, and comparison to administration of immune globulin. J Hepatol 18: S32–S37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha MP, Scott RM, Joshi DM, Mammen MP Jr, Thapa GB, Thapa N, Myint KS, Fourneau M, Kuschner RA, Shrestha SK, et al. 2007. Safety and efficacy of a recombinant hepatitis E vaccine. N Engl J Med 356: 895–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Smith DB, Simmonds P. 2018. Classification and genomic diversity of enterically transmitted hepatitis viruses. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 10.1101/cshperspect.a031880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sonoda H, Abe M, Sugimoto T, Sato Y, Bando M, Fukui E, Mizuo H, Takahashi M, Nishizawa T, Okamoto H. 2004. Prevalence of hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection in wild boars and deer and genetic identification of a genotype 3 HEV from a boar in Japan. J Clin Microbiol 42: 5371–5374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su AI, Pezacki JP, Wodicka L, Brideau AD, Supekova L, Thimme R, Wieland S, Bukh J, Purcell RH, Schultz PG, et al. 2002. Genomic analysis of the host response to hepatitis C virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99: 15669–15674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M, Tanaka T, Takahashi H, Hoshino Y, Nagashima S, Jirintai, Mizuo H, Yazaki Y, Takagi T, Azuma M, et al. 2010. Hepatitis E Virus (HEV) strains in serum samples can replicate efficiently in cultured cells despite the coexistence of HEV antibodies: Characterization of HEV virions in blood circulation. J Clin Microbiol 48: 1112–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]