Abstract

Inner ear malformations are recognized by imaging in about 20% of children with congenital sensorineural hearing loss. Normal development of the inner ear structures can be affected by many factors, including genetic anomalies as well as environmental destructive causes (ischemic, infectious, radiation and more). Recently, histopathological studies have provided new insights on the anatomy and pathogenesis of inner ear malformations, especially regarding incomplete partition and cochlear hypoplasia (CH), for which different subtypes have been identified. Factors known for interfering with normal inner ear development are numerous and sometimes act simultaneously, making the understanding of their pathophysiology more challenging. Vascular supply from the internal auditory canal seems to be critical for normal development of internal structures of the labyrinth while a premature arrest in the spatial development of the cochlea due to genetic or toxic factors may result in short cochlea (i.e.: CH). The aim of this essay is to show 3 T MRI appearances of the different subtypes of CH and incomplete partition introduced in the new classification (findings summary in Table 1).

MRI protocol for inner ear malformations

Main purposes for cross-sectional imaging in patients with sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) are: to identify a possible malformation of the inner ear, define the anatomy of the temporal bone, study the auditory pathway from the cochlear nerve to the auditory cortex, identify associated brain anomalies and identify prognostic factors.1 MRI with three-dimensional (3D) heavily T2 weighted gradient-echo sequence allows a spatial resolution of up to 0.4 mm. Sagittal, coronal and oblique reconstructions can be performed. This means that not only cochlear and facial nerves can be better displayed, but also the modiolus, lamina spiralis and interscalar septum (ISS) can be visualized in details (Figure 1).2 High-resolution CT is not able to show neither early cochlear obliteration nor central causes of hearing loss,3 but is still necessary for pre-operative assessment of cochlear implants.4 Of note, cone beam CT is an increasingly used tool that has shown to be able not only to assess middle ear and ossicular anomalies with superior performances compared to multidetector CT, but also to depict inner ear structures with extraordinary anatomical detail and with lower radiation dose.5

Figure 1.

High-resolution axial T2 WI 3D of a normal cochlea. Note the ability of MRI to show not only cochlear nerve (black arrowhead), but also osseous structures such as interscalar septum (short white arrow) and modiolus (long white arrow) with associated lamina spiralis. 3D, three-dimensional; T2 WI, T2 weighted imaging.

As a standard “pediatric SNHL protocol”, we use a combination of specific sequences on inner ears and also standard brain sequences that allow demonstration of other causes of SNHL (e.g. kernicterus) and associated findings common in syndromic conditions:

3D-T2 WI BALANCE/DRIVE on axial plane including the inner ears with parasagittal reformats on the internal auditory canal.

Brain axial and coronal T2 weighted sequence.

Brain axial FLAIR.

Brain 3D-T1.

Brain DWI or DTI.

Extensive literature is also available regarding inner ear measurement for the diagnosis of inner ear malformations and surgical planning of electrode implantation.6–8

Inner ear malformations

Cochlear hypoplasias

Cochlear hypoplasias (CHs) constitute between 15 and 23% of inner ear malformations.9 In this group of anomalies, the cochlea is clearly separated from the vestibule, but its external dimensions are small.10 There are four types of CHs. Internal architecture may or may not be normal, depending on the subtype.11

Given that otic capsule ossification does not start until the membranous labyrinth reaches full size, CH is supposed to be caused by an arrest of development between sixth and eighth week, except for CH Type 4 (CH-4).

In CHs Type 1 and 2 (CH-1 and CH-2), in addition to a small-sized cochlea, there is arrested development of the internal architecture most likely due to abnormal blood supply from Internal Auditory Canal (IAC); therefore, there is a smaller and incompletely partitioned cochlea.

On the other hand, CHs Type 3 and 4 (CH-3 and CH-4) are most probably genetically predetermined to have a smaller size due to the fact that development of the membranous labyrinth stops at a point earlier than expected. As a result, they are smaller versions of normally partitioned cochleas.

Cochlear hypoplasia Type 1

This is the most severe form of CH, it consists of a bud-like (round, ovoid) appearing cochlea with no internal architecture and variable bony separation with the internal acoustic meatus (IAM) (Figure 2). Usually, the cochlear nerve is hypoplastic or absent.

Figure 2.

Cochlear hypoplasia Type 1 (CH1) in a 7-month-old male with bilateral profound hearing loss. High-resolution axial T2 WI 3D (a) and CT (b) showing a small cochlear bud with less than one turn and no internal structure compatible with CH1 (arrows); deformed vestibule and SCCs are also present. Axial T2 CISS at the level of the IAM demonstrates presence of both VIII and VII cranial nerves (dotted arrow and short arrow respectively in c). Labyrinthine malformations were symmetrical on both sides in this patient. 3D, three-dimensional; CISS, constructive interference in steady state; IAM, internal acoustic meatus; SCC, semi-circularcanal; T2 WI, T2 weighted imaging.

Cochlear hypoplasia Type 2

This CH is characterized by small size, hypoplastic or absent ISS, partial modiolar development with a normal modiolar base. Bony cochlear nerve canal and cochlear nerve can be normal.

External normal shape in this type of CH can be relatively preserved with only slightly rounded appearance due to absence or hypoplasia of the ISS (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Cochlear hypoplasia Type 2 (CH2) in a 3-month-old male with Pierre-Robin sequence and bilateral profound hearing loss. High-resolution axial T2 WI 3D shows a small cochlea with underdeveloped modiolus (arrow) and lamina spiralis (dotted arrow). The VII/VIII nerves are present on both sides (visible only on the left in the image). Coexistence of incomplete internal cochlear structure and small cochlear dimension is in keeping with CH2. 3D, three-dimensional; T2 WI, T2 weighted imaging.

Cochlear hypoplasia Type 3

In this type, relatively frequent,11 the cochlea has an almost normal architecture with regular ISS, modiolus and lamina spiralis, with normal otic capsule. However, the modiolus is shorter than normal and the cochlea has reduced size (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cochlear hypoplasia Type 3 (CH3) in a 4-year-old female with bilateral profound hearing loss. High-resolution axial T2 WI 3D shows a small cochlear with presence of fairly complete interscalar septum (arrow in a) and lamina spiralis (arrows in b, c). Only the VII nerve was clearly visualized within the IAM (dotted arrow in c). Vestibule and SCCs are hypodeveloped. 3D, three-dimensional; IAM, internal acoustic meatus; SCC, semi-circularcanal;T2 WI, T2 weighted imaging.

Associated findings are vestibule and semicircular canal hypoplasia, stapes fixation and oval window aplasia.

Cochlear hypoplasia Type 4

It is rare and bilateral. The basal turn is normal both in size and morphology, and middle and apical turns are hypoplastic. Modiolus is present. Therefore, the overall size is small (Figure 5). Difference between CH 3 and 4 is that in Type 3 the basal turn is smaller, while it is normal in Type 4. Interestingly, the few cases described have the same aberrant course of the labyrinthine segment of the facial nerve.12

Figure 5.

MRI of the inner ears in a 10-year-old female with chronic kidney disease, dysmorphic features, bilateral hearing loss and mosaic trisomy of chromosome 22. Bilateral CH4 is demonstrated with normal-sized basal turn and very hypoplastic upper turn. Normal lamina spiralis is noted as a hypointense line within the basal turn (arrows).

Since, only the middle and apical turns do not develop properly, it has been proposed that the insult happens between 10th and 20th weeks.11

Incomplete partition anomalies

Incomplete partition (IP) anomalies constitute a group of anomalies in which the cochlea is normal in size and clearly differentiated from the vestibule. However, internal architecture is anomalous and the differentiation of these entities relies on identification of such internal structure anomalies13 (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Different types of IP with CT (top row) and MRI (low row) correlation. High-resolution CT and high-resolution axial T2 WI 3D in patients with IP-1 (a/a’), IP 2 (b/b’) and IP-3 (c/c’) showing similar diagnostic value of CT and MRI in identifying the type of malformation with an added value of MRI in characterising the internal cochlear structures (i.e.: modiolus and lamina spiralis) and visualisation of VIII and VII nerves. (a) Typical cystic cochleovestibular malformation of IP-1 with absence of internal structure of the cochlea and dilatation of vestibule and SCCs. The cochlear nerve was present but hypoplastic (not shown). (b) Mondini triad: dilated apical turn of the cochlea (arrow in b’) without internal structure (IP-2) but with normal basal turn, slightly dilated vestibule and markedly dilated vestibular aqueduct (dotted arrow in b’). (c) IP-3 (X-linked deafness): typical appearances of the cochlea with presence of interscalar septum (dotted arrows in c’) but absence of internal structures. Slightly dilated and malformed SCCs and vestibule are also present. 3D, three-dimensional; IP, incomplete partition; SCC, semi-circularcanal;T2 WI, T2weighted imaging.

Audiological intervention is determined according to the type and degree of hearing loss.14

Incomplete partition Type 1 (IP-1)

The pathophysiology of this anomaly is similar to that of CH1 and 2 implying a deficient vascular supply with consequent lack of development of internal structures. A defective stapes footplate is seldom associated.11 However, there is no arrest in the membranous labyrinth development with a normal or near normal sized cochlea. In most of cases, the modiolus is defective, but present (subtotal modiolar defect).

There is also an associated dilated vestibule.6, 13

IP1 are almost always associated with severe/profound SNHL. Therefore, if the cochlear nerve is present, the main treatment for these patients is cochlear implantation.14

The presence of a thin base of the modiolus may explain the relative infrequency of cerebrospinal fluid leak after cochleostomy in IP-1 patients.

Incomplete partition Type 2 (IP-2)

It corresponds to the anomaly described by Mondini in 1971.11 It is characterized by normal cochlear size, hypoplastic modiolus and cystic dilatation of the apex due to an apical ISS defect (between middle and apical turns). Histologically, there is enlargement of scala vestibuli, ISS appears to be pushed upwards, scala tympani is normal.11, 15 Associated anomalies are an enlarged vestibular aqueduct and slight dilatation of the vestibule. There is no stapes footplate defect and the otic capsule layers are fully developed.

Regarding the pathogenesis, one of the possible explanations is that the primary anomaly is a genetically determined disorder of the endolymphatic sac with excessive endolymph secretion that may lead to enlargement of the vestibular aqueduct, causing the retrograde transmission of cerebrospinal fluid pulsating pressure into the cochlea. The high pressure may determine the modiolar defect and dilatation of scala vestibuli and vestibule. According to this theory, IP-2 is not a milder form of IP-1, since pathogenesis is different.

Audiologic findings can vary from normal hearing to profound hearing loss.14

Incomplete partition Type 3 (IP-3)

In this case, external dimensions of the cochlea are preserved and interscalar septa are present. However, modiolus is absent with absent bony partition between the fundus of the IAM and the basal turn of the cochlea. The IAM is dilated. In addition, the otic capsule is thinner than in other IP patients and it seems to be formed only by a thick endosteal layer (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

IP-3, same patient as in Figure 6c. Axial T2 WI 3D showing bilateral and symmetrical IP-3 malformation: note the large IAMs, the presence of VIII nerves with cochlear and vestibular divisions and the absence of internal structure, wide cochlear aperture and normal interscalar septum (white arrows). Such findings are encountered in X-linked deafness due to POU3F4 gene mutation. 3D, three-dimensional; IAM, internal acoustic meatus; IP, incomplete partition; T2 WI, T2 weighted imaging.

An association between IP-3 malformation and X-linked deafness with POU3F4 gene mutation is known. The pathogenesis of this association is thought to be due to a genetic defect causing an abnormal vascular supply from the middle ear mucosa and therefore absence of the external otic capsule layers.

Due to its characteristics, there is a high risk of gushing during stapes manipulation.16

Audiologic findings are extremely variable; progressive severe to profound mixed SNHL appears to be the most frequently encountered.14

Cochlear anomalies in syndromic SNHL

Approximately, 50% of pediatric SNHL are genetic and 30% of these are syndromic in nature. Associated anomalies involve the eye, the kidney, the musculoskeletal and the nervous systems; others are associated with skin/hair disorders such as pigmentation anomalies.

There are numerous syndromes associated with SNHL; among them, Pendred and Usher syndromes are the most frequent ones.17 However, in many of these syndromes hearing loss is an inconstant feature. On the other hand, a few syndromes are described in which SNHL is a major and almost constant feature. Among them, a small subgroup present with gross inner ear anomalies at imaging16 (Table 2) (Figures 7,8,9,10).

Table 2.

Main syndromic causes of SNHL and major associated inner ear anomalies

| Syndrome | Inner ear anomalies | Other main features |

| BOR spectrum disorders Figure 8 and Supplementary Figure 1) | Major features are: | |

| CHARGE syndrome (Figure 9) | Major features are: coloboma, choanal atresia, rhombencephalic dysfunction, hypothalamohypophyseal dysfunction, abnormal middle or external ear, malformation of mediastinal organs (heart, esophagus), mental retardation |

|

| Waardenburg syndrome (SOX 10 mutation) (Figure 10) | ||

| Alagille syndrome | Aplasia or hypoplasia of the posterior SCC (similarly to Waardenburg) | Major features are: |

| Down syndrome | Multisystemic disease with a wide variety of anomalies involving nervous, cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal and musculoskeletal systems. | |

| X-linked deafness (Figure 7) | Features of IP-3, including: | No systemic features |

| Pendred syndrome | Features of IP-2, including: | Euthyroid goiter |

IAC, internal auditory canal; SCC, semi-circularcanal; SNHL, sensorineural hearing loss.

Table 1. .

Summary of main characteristics of cochlear hypoplasias and incomplete partitions

| Anomaly | Main characteristics |

| CH Type 1 | |

| CH Type 2 | |

| CH Type 3 | |

| CH Type 4 | |

| IP-1 | |

| IP-2 | |

| IP-3 |

IAC, internal auditory canal; ISS, interscalarseptum.

Figure 8.

3D T2 WI in a 2-year-old male with BOR syndrome. There is hypoplastic cochlea (dotted arrow in A) with small and dysmorphic apical portion and deficient internal structure (fitting the description of CH Type 2). Lamina spiralis is visible in the basal turn (short arrow in a). VIII nerve and cochlear division are present (long white arrow in a and black arrow in b, respectively). Lateral SCC is small (white arrow in b) and the posterior SCC is absent (i.e.: persistent anlage; arrowhead in b). 3D, three-dimensional; SCC, semi-circular canal; T2 WI, T2 weighted imaging.

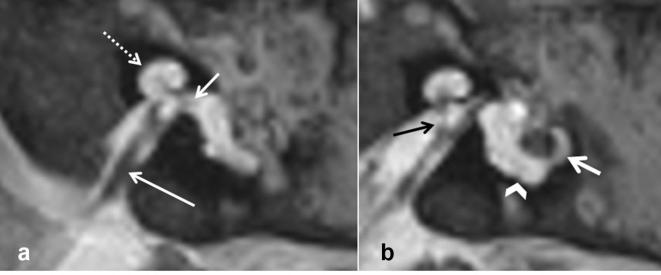

Figure 9. .

3D T2 WI in an 1-year-old female with CHARGE syndrome. Right labyrinth (a) shows a small cochlea with markedly deficient internal structure in keeping with CH Type 2; slice at the level of the IAM on the right demonstrates very hypoplastic cochlear and vestibular nerves (arrows in b). On the left side (c) there is a small cochlear bud (CH Type 1, arrowhead), the IAM is very small and the nerves are not visualized (arrow). On both sides the vestibule is hypoplastic and dysmorphic and the SCCs are not present. (d) Axial CT of the right otic capsule demonstrating CT appearance of the right hypoplastic cochlea. 3D, three-dimensional; IAM, internal acoustic meatus; T2 WI, T2 weighted imaging.

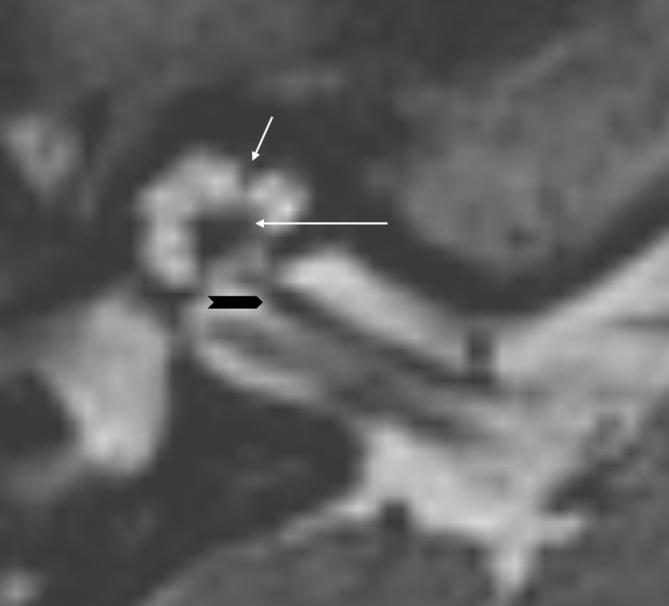

Figure 10. .

3D T2 WI in a 2-year-old male with SOX 10 mutation (a, b) shows globally small cochlea with relatively preserved internal structure (CH Type 3). The lateral SCC is small and dysplastic (arrow in a) and posterior SCC is not present (i.e.: persistent anlage, dotted arrow in a). Superior SCC was also slightly small and there were hypoplastic ophthalmic nerves (not shown). The corresponding CT appearances are shown in c and d. Difference between CH3 and 4 is that in the Type 3 the basal turn is also smaller while preserved in Type 4. Inner ear malformations in this patient were symmetrical on both sides. 3D, three-dimensional; SCC, semi-circular canal; T2 WI, T2 weighted imaging.

Contributor Information

Giacomo Talenti, Email: giacomo.talenti86@gmail.com.

Renzo Manara, Email: rmanara@unisa.it.

Davide Brotto, Email: davidebrotto@hotmail.it.

Felice D'Arco, Email: darcofel@gmail.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Huang BY, Zdanski C, Castillo M. Pediatric sensorineural hearing loss, part 1: practical aspects for neuroradiologists. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012; 33: 211–7. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trimble K, Blaser S, James AL, Papsin BC. Computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging before pediatric cochlear implantation? Developing an investigative strategy. Otol Neurotol 2007; 28: 317–24. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000253285.40995.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nikolopoulos TP, O'Donoghue GM, Robinson KL, Holland IM, Ludman C, Gibbin KP. Preoperative radiologic evaluation in cochlear implantation. Am J Otol 1997; 18(6 Suppl): S73–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parry DA, Booth T, Roland PS. Advantages of magnetic resonance imaging over computed tomography in preoperative evaluation of pediatric cochlear implant candidates. Otol Neurotol 2005; 26: 976–82. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000185049.61770.da [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahmani-Causse M, Marx M, Deguine O, Fraysse B, Lepage B, Escudé B. Morphologic examination of the temporal bone by cone beam computed tomography: comparison with multislice helical computed tomography. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis 2011; 128: 230–5. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2011.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D'Arco F, Talenti G, Lakshmanan R, Stephenson K, Siddiqui A, Carney O. Do measurements of inner ear structures help in the diagnosis of inner ear malformations? A review of literature. Otol Neurotol 2017; 38: e384–e392. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar JU, Kavitha Y. Application of curved MPR algorithm to high resolution 3 dimensional T2 weighted CISS images for virtual uncoiling of membranous cochlea as an aid for cochlear morphometry. J Clin Diagn Res 2017; 11: TC12–TC14. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/23206.9456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Escudé B, James C, Deguine O, Cochard N, Eter E, Fraysse B. The size of the cochlea and predictions of insertion depth angles for cochlear implant electrodes. Audiol Neurootol 2006; 11(Suppl 1): 27–33. doi: 10.1159/000095611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cinar BC, Batuk MO, Tahir E, Sennaroglu G, Sennaroglu L. Audiologic and radiologic findings in cochlear hypoplasia. Auris Nasus Larynx 2017; 44: 655–63. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2016.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sennaroglu L, Saatci I. A new classification for cochleovestibular malformations. Laryngoscope 2002; 112: 2230–41. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200212000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sennaroglu L. Histopathology of inner ear malformations: do we have enough evidence to explain pathophysiology? Cochlear Implants Int 2016; 17: 3–20. doi: 10.1179/1754762815Y.0000000016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sennaroğlu L, Bajin MD, Pamuk E, Tahir E. Cochlear hypoplasia type four with anteriorly displaced facial nerve canal. Otol Neurotol 2016; 37: e407–e409. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sennaroglu L, Saatci I. Unpartitioned versus incompletely partitioned cochleae: radiologic differentiation. Otol Neurotol 2004; 25: 520–9. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200407000-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Özbal Batuk M, Çınar BÇ, Özgen B, Sennaroğlu G, Sennaroğlu L, BÇ Çınar, Sennaroğlu L. Audiological and radiological characteristics in incomplete partition malformations. J Int Adv Otol 2017; 13: 233–8. doi: 10.5152/iao.2017.3030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leung KJ, Quesnel AM, Juliano AF, Curtin HD. Correlation of CT, MR, and histopathology in incomplete partition-II cochlear anomaly. Otol Neurotol 2016; 37: 434–7. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang BY, Zdanski C, Castillo M. Pediatric sensorineural hearing loss, part 2: syndromic and acquired causes. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012; 33: 399–406. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koffler T, Ushakov K, Avraham KB. Genetics of hearing loss: syndromic. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2015; 48: 1041–61. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2015.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]