Abstract

Background

There is a growing recognition that patient engagement is necessary for the cultivation of patient- and family-centered care (PFCC) in the hospital setting. Acting on the emerging understanding that hearing stories from our patients gives valuable insight about our ability to provide compassionate PFCC, we developed an educational patient experience curriculum at our acute care teaching hospital.

Objectives

To understand the benefits and consequences of patient storytelling and to explore the impact of our curriculum on participants.

Methods

The curriculum was codesigned with patients to illustrate the value and meaning of PFCC to health professional audiences. We surveyed audience members at nursing orientation events and interviewed the patient storytellers who shared their stories.

Results

Participants indicated that patient stories could serve as lessons or reminders about the dimensions of PFCC and could inspire changes to practice. Storytellers reported an immensely rewarding experience and highlighted the value of educating and connecting with participants. However, they reported that the experience could also pose emotional challenges.

Conclusion

Careful and considerate facilitation of storytelling sessions is crucial to the delivery of a curriculum that is beneficial to both patients and participants. Our storytelling framework offers a novel approach to engaging patients in education, and it contributes to our existing understanding of how patient engagement efforts resonate within organizations.

INTRODUCTION

Patient perspectives have become central to the planning, delivery, and evaluation of health care services in recent years.1–4 There is a growing recognition that active participation of patients and their families in health care settings is essential for cultivating patient- and family-centered care (PFCC).5–8 In turn, the provision of PFCC is associated with improved patient satisfaction and outcomes.9–13 As patients have become increasingly engaged across health care initiatives, patient storytelling has emerged as a way of teaching health professionals and hospital staff the dimensions of delivering PFCC.14–17 There is evidence that patient and family stories can generate valuable insight for practitioners into the patient experience by evoking an emotional response, motivating listeners to reflect on their practice, and delivering relevant educational content.14,18–20

The design of the workshop and curriculum we outline herein resonates with concepts from narrative medicine, which is defined as a clinical practice of developing more empathetic relationships between medical clinicians and patients.15 Medicine practiced with narrative competence recognizes, absorbs, interprets, and is moved by the stories of illness.15 The ideas from this clinical practice method can be used to teach all practitioners to deeply understand the experience of illness and care through the telling and receiving of patient stories. Offering these stories, which are told directly from patients and received in person by health care practitioners for discussion, helps remind us of more patient-centered practices. This may be a key factor in helping advance a better understanding of the patient experience, improving quality and safety, and shifting cultural norms in health care environments.15

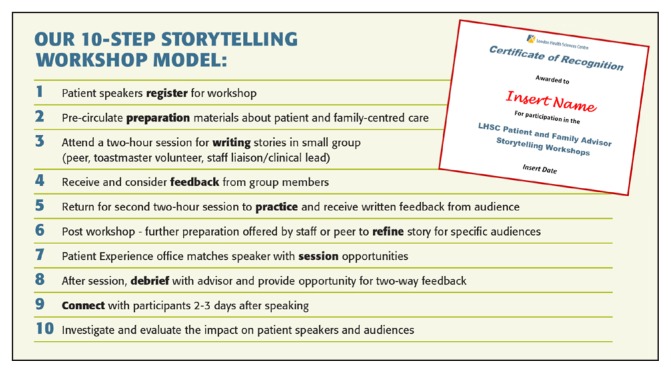

Acting on this emerging understanding that patient and family stories deliver insight and deeper understanding into our ability to provide PFCC, the Patient Experience Office of London Health Sciences Centre in London, Ontario, Canada, established an inhospital patient storytelling curriculum in 2014. A growing group of patient storytellers seeks to influence health professionals by promoting compassionate communication, empathy, and an understanding of authentic PFCC values. We have facilitated more than 60 sessions, delivering patient stories to more than 1500 new employees and existing staff at corporate orientations, nursing orientations, grand rounds, and hospital education sessions. We codesigned a 2-part workshop with patients for preparing and supporting patient and family storytellers for this role, to support the sharing and receiving of stories, and to engage storytellers in an interactive discussion (Figure 1). Here, we outline our storytelling workshop and discuss the impact of involvement in the curriculum on both storytellers and audience participants.

Figure 1.

A 10-step storytelling workshop model used to prepare and support patients in their role as storytellers.

LHSC = London Health Sciences Centre.

METHODS

Storytelling Workshops and In-hospital Education Sessions

This study received institutional research ethics approval from Western University and Lawson Health Research Institute, both in London, Ontario, Canada. Potential storytellers for inhospital education sessions were drawn from a variety of areas, including Patient and Family Advisory Councils, a recommendation from a health care practitioner, from the hospital Patient Relations Office, and were then invited to participate in a two-part workshop. Recruitment of storytellers was based on a willingness to share information about their experiences, passion for improving the patient experience, ability to use their personal experience constructively, respect for diversity and differing opinions, comfort with public speaking, and openness to feedback. The goal was to develop storytellers who would share an assortment of health care stories with audiences in various inhospital education sessions. The storytellers would draw on their experiences as patients and family members, recounting a broad range of experiences regarding illness, treatment, and caregiving.

The objectives of the storytelling educational curriculum were 1) to promote health care practitioners’ professional identities and an overall environment to sustain compassionate care and 2) to provide an authentic and emotional dialogue for the educational curriculum. By including patient and family stories in our hospital’s employee orientation and internal curriculum, we invited participants to reflect on their practice and to consider the attitudes and actions that are important for PFCC. Furthermore, building a culture of patient and family storytelling in the work environment would allow us to continually remind employees of our vision for engaging partnerships and the provision of exceptional experiences. Finally, patients offer a window into real experiences of care, which helps us understand what we are doing well and what can be improved. We share and discuss stories that are both heartbreaking and uplifting to detail the impact of patient experiences and to help expose the value of enhancing compassion, reflecting on their own skills such as matters of listening carefully and connecting with others, communication and relationship-building skills, and demonstrating caring attitudes towards patients.

Before formally sharing their experiences in the education sessions, storytellers were prepared for this role in a two-part workshop. An organizing committee composed of patient and family advisors, hospital staff, and employees of the Patient Experience Office were involved in the planning and delivery of storyteller workshops.

Before the workshop, storytellers were provided with materials such as the Principles, Definitions, and Vital Behaviors of Patient- and Family-Centered Care (Table 1). These background materials offered prompts to assist the storytellers in organizing their thoughts so they could attend the workshop with a draft story written that described moments from care and illustrated PFCC or lack thereof. We created this handout, adapted from information from the Institute for Patent- and Family-Centered Care,21 to orient both storytellers and session participants to the core concepts, behaviors, and actions of PFCC. In the workshops, patients construct stories to illustrate PFCC moments, which are intended, in the educational sessions, to spark both dialogue and an opportunity for reflective practice and deeper understanding.

Table 1.

Principles, definitions, and vital behaviors of patient- and family-centered care

| Principle and definition | Proposed behaviors: Actions and attitudes of health care practitioners |

|---|---|

| Dignity and respect | |

| Patient and family perspectives and choices are heard and honored. Patient and family knowledge, values, beliefs, and cultural backgrounds are incorporated into care planning and decision making. |

Ask patients to define their “family,” understanding that it may include friends and others from their community. Discuss with each patient to ensure that whomever the patient defines as “family” is considered to be “a partner in care.” Acknowledge patients and families as the experts of their own experience, with information that must be heard and acted on. |

| Communication and information sharing | |

| Health care practitioners share complete and unbiased information with patients and families in ways that are clear, complete, timely, accurate, and useful in helping patients and families effectively participate in care and decision making. Patients and families also share all necessary and relevant information with members of their care team. |

Introduce yourself, what your role is, and what they can expect from you. Ask patients and families how else you can assist them. Inquire to find out from patients/families about how to share information/education. What do they want in terms of the amount, how often, what format, and when? Tell patients/families what the diagnosis is and the seriousness as soon as possible. Don’t hold back the truth. Be open, up front, and realistic about the treatment, appointments, process, options, side effects, etc. Encourage and answer questions. In conversations with patients and families, use appreciative inquiry, and be attentive with reflective listening to ensure two-way communication and full understanding—use a “teach back” technique. |

| Collaboration and empowerment | |

| Patients, families, and health care practitioners collaborate in policy and program development, in professional education, in research and evaluation, and in the delivery of care. Patients are empowered to participate in experiences that enhance control and independence. |

Educate patients and families about their important role in ensuring their safety and welcome them to ask questions and voice concerns. Ensure that patients and families know who and how to call for help. Ensure that patients and families always know who different staff are, and what they are doing; staff should state their names and occupation, and explain what they are doing. |

| Comprehensive and coordinated | |

| Patients and families receive care that provides physical and emotional comfort and is safe. Patients and families experience care that has continuity and smooth transitions. |

Show caring, compassion, and empathy through: Eye contact, listening, taking time, and giving your full attention—be present in the moment. Provide support for patients/families: Be knowledgeable of what is available to them; suggest and refer to social work, spiritual care, and dietetics, for example. Prepare well for transitions between different practitioners and phases of care (eg, hospital to home). |

At the initial workshop, members of the organizing committee, veteran peer storytellers, and members of Toastmasters International clubs partnered with the new storytellers to assist with the storytelling process, which included not only the structure and organization of the story but also public speaking tips for effective delivery. The Toastmasters volunteers were chosen primarily for their expertise in this regard. The role of the peer storytellers and Toastmasters was not to help write or edit the stories so much as to reflect to the storytellers what they had heard and to help ensure that the individual storyteller’s message was being conveyed as intended.

At the next workshop, storytellers were given an opportunity to rehearse their stories and to receive feedback from the same group in a supportive and safe environment. This session focused more on the delivery of the story, with the goal of instilling comfort and confidence in the public speaking process, as well as ensuring that the story reflected the principles of PFCC. After becoming more comfortable with their story, storytellers worked with the hospital staff to deliver curriculum that was based on their lived experience across a wide range of educational sessions for health care practitioners, staff, and administrators. The Sidebar: Sample Patient Stories illustrates examples of patient stories that were prepared and shared in the educational curriculum at our center.

Survey of Educational Session Participants

This study focused solely on the audience members in one aspect of the curriculum: Nursing orientation. After the storytelling session at nursing orientation events, the study was introduced to audience members by a medical student summer research trainee (TR) who had no prior involvement with the curriculum or participants. Audiences were composed of new nursing graduates, as well as experienced nurses who were newly hired by our center. The survey was distributed to all audience members, along with a letter of information. Participants were given an opportunity to ask questions before providing written informed consent. The survey questions were designed to explore the perceived benefits, consequences, and impact of listening to patient stories. Participants were asked to provide short answers to questions, as well as ratings on a 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree, disagree, agree, strongly agree, not applicable) regarding the presentation and presenters. The survey took approximately 5 minutes to complete.

Interviews with Patient Storytellers

To generate insight into the social process of educating health professionals as a patient storyteller, we used semistructured interviews following the grounded theory method. The constructivist grounded theory method, with its emphasis on social process and interactionism, allowed us to explore what storytellers experience through the social process of sharing their experience for educational purposes. Semistructured interviews were the data collection method used to gather these insights. Initial contact with the 33 storytellers involved in the curriculum was made via an e-mail sent by the student researcher (TR). Twenty-six storytellers responded to the invitation to participate, and 25 could be scheduled for an interview. No refusals to participate were made. The interviews were approximately 30 minutes in length and were carried out by the student researcher (TR). Participants chose the location of their interview, whether at the hospital or another public space. Interviews were guided by questions that explored the perceived benefits, consequences, and impact of sharing health care stories. Each interview was audiorecorded and transcribed verbatim without identifying information.

Using a constant comparative process, inductive thematic analysis was performed to organize the data into conceptual categories. Data collection and analysis took place concurrently such that each process informed the other, and theoretical sampling was thereby used to shape subsequent interviews. The coding structure was developed through a collaborative effort by the research team, and the finalized codes were applied to the complete dataset. A qualitative data analysis software (NVivo Version 10.2.2, QSR International, Burlington, MA) was used to organize and support the analysis.

RESULTS

Survey Results: Impact on Nursing Participants

The storytelling curriculum was well received by participants at a nursing orientation. Of the 542 respondents to our survey collected from June 2014 to February 2017, a total of 540 (99%) agreed or strongly agreed the program provided them with new or valuable information, and 506 (93%) agreed or strongly agreed that they were inspired to consider changing something in how they perform their job. Many participants indicated that the experience of hearing patient stories was “real,” “personal,” “honest,” or “relatable.” Stories could serve as an educational lesson in PFCC, a reminder of a previously learned lesson, or as inspiration to carry forward into practice. Although the survey feedback was largely positive, participants who provided critical feedback called for the delivery of a broader range of stories and perspectives to further enrich their learning.

Sample Patient Stories.

An example of a positive patient story that demonstrates empowerment and addresses patient fear and anxiety:

“My husband and I arrived at the clinic for my first chemotherapy. As much as things are explained to you, it is still a scary time, and we were both feeling anxious and afraid. Once the [intravenous] line was in place on my forearm and the nurse was just about to start the first drug, she looked at us both and said, ‘If there is anything you’d like to say to your tumor, now is the time to say it.’ I cannot repeat the conversation, but what I can tell you is, in that moment, both my husband and I felt empowered … . We no longer were afraid. With those few words, she gave us hope that we could do this. She helped both my husband and myself experience some control.”—Mim O’Dowda, patient with Hodgkin lymphoma, Stage 3 cancer

An example of a negative patient story that demonstrates the importance of information sharing and coordinated care:

“As a transplant patient I had it drilled in how critical my medications are. I remember a social worker trying to stress to me the importance of never forgetting my antirejection medication and saying that missing my dose by even an hour could set up my kidney for rejection. I am not sure how true that is, but my kidney was a precious gift, and I never wanted it to fail, so I must admit that I have become a little obsessive with medication. Two years ago I developed breathing difficulty. The doctors had checked me over and done chest x-rays but could find nothing wrong. However, over the course of about six weeks I became so weak and short of breath that I was admitted to the hospital. When [I was] first seen in the clinic that day, they suspected I may have a pulmonary embolism so talked about the possibility of putting me on a blood thinner to break up the clot. However, later during the day I had a [computed tomography] scan done; no embolism was found, so instead the doctors determined they would begin a course of antibiotics and ordered a lung biopsy to be done the following day. That night my nurse came in with my meds. I was not feeling well, and the last thing I wanted to do was check what medication I was taking. I often find that in hospital they give different size tablets or different brands than what I take at home, and it is confusing. I noticed a couple of different pills and asked what they were; my nurse explained that they were my antibiotic and my blood thinner. I responded that I was not on a blood thinner and they had decided not to give me one. It caused considerable confusion for the nurse and anxiety for me. I believe what happened is that the original order for the blood thinner in the clinic was not canceled. This could have jeopardized the lung biopsy the following day or caused me complications if they had not realized I had taken a blood thinner. It often seems that it is during times of transition—as a patient moves from one department or floor to another or one shift to another—that trust is developed and reassurance is needed that our caregivers know our stories and concerns.” —Bonnie Field, patient with monoclonal gammopathy; transplant and dialysis recipient

An example of a positive patient story that illustrates the value of communication, empowerment, and patient advocacy:

“The doctor I met with to receive my cancer diagnosis was not my regular physician, but rather a young locum [tenens] just filling in for the day. We had no existing relationship, but suddenly she was going to become a significant player in my life—being the one to deliver this difficult news to me. And, thankfully, she could not have been better at her job that day. She was direct, informative, patient, and compassionate—all in appropriate measure. And then she did one other thing for me that was even more important and groundbreaking. She deliberately circled back to the last nine weeks and all the frustrating delays, which she sincerely apologized for despite having absolutely nothing to do with the problems herself. She said it appeared as though I might have a bit of a long haul ahead of me, and she said, ‘You have to demand more from the health care system and your providers going forward.’ She told me my natural passivity had to take a backseat for a while, because I would need to advocate for myself and to find my voice when it came to playing an active role in my care. In short, she gave me permission to ask for more—for more information, for more questions, and for more input into the process that would unfold over the next two years. And that permission, coming from that source—a provider—did so much to make me feel like a valued member of my health care team and empower me throughout my journey.”—Lauren Lee, patient with ductal carcinoma in situ breast cancer

An example of a negative patient story that demonstrates the importance of family inclusion, patient input, and knowledge:

“While I was waiting for a diagnosis to be confirmed, I had to go to the Emergency Department every 7 to 10 days to have my pleural cavity drained, which is a procedure where a needle is inserted between the ribs and into the pleural cavity, which is the space that surrounds each lung. My husband was present at each one and got to know which needles were more painful than others, how I needed to be sitting, and how many containers they would fill. The nurse brought the supplies in for the procedure, and my husband told her she would need at least 2 more containers. She assured him she knew what she was doing, but my husband repeated himself and explained that we had been through this several times before. She chose to ignore him. Half way through my procedure the physician was calling for more containers. I had to sit there motionless with this needle in my chest while she scrambled for more containers.”—Mim O’Dowda, patient with Hodgkin lymphoma, Stage 3 cancer

Stories as Lessons

When surveyed about the impact of hearing patient stories and what they liked about the presentation, many participants emphasized the educational value of patient perspectives. The curriculum was reported to be highly informative, helping participants to develop a “much better understanding of the patients’ and families’ situation and needs.” For instance, one participant indicated that s/he had learned to take time with the patient and family after delivering negative news, to avoid medical jargon, and to allow time for the patient to ask questions. With new insight, participants explained that they could recognize areas for improvement that would have otherwise gone unnoticed. Audiences found both positive and negative stories valuable—for instance, a story from a patient who felt valued and empowered by the practitioners who delivered her cancer diagnosis, or a patient who felt ignored and disregarded by the team during a painful procedure (see Sidebar: Sample Patient Stories).

Many participants highlighted the helpfulness of hearing “the good, the bad, and the ugly” or “how nurses contribute to both positive and negative experiences.” Although negative stories could “trigger emotion,” they provided meaningful and constructive criticism. Conversely, positive stories allowed participants to celebrate and take pride in their role as health care practitioners.

Stories as Reminders

Participants indicated that patient perspectives served as a reminder of the dimensions of PFCC. Some audience members had received education surrounding this standard of care but admitted that they often overlooked the patient experience when “things get hectic on the floor.” After hearing patient stories, participants indicated that they were reminded of the “little things” that make a difference to patient care, such as “treating patients as people,” “warm blankets and pillows,” “patients are more than their diagnoses,” “introducing self,” and “individualized needs.” Furthermore, a number of participants described how they were reminded of why they chose a career in nursing after hearing about the effect that individual health care practitioners could have on the patient experience.

Stories as Inspiration

Some participants reported feeling inspired after the storytelling session. Patient perspectives not only helped participants to recognize areas for improvement but also motivated them to make changes to their practice to improve care. Participants were inspired to foster improvement in specific situations, as well as in broader contexts. For example, one participant indicated being inspired to “assess how I interact with patients and how I can best comfort them,” whereas another expressed finding the inspiration to “be a better health care practitioner.”

When participants were asked to indicate what they would change about the presentation and what they would like to learn more about, most left the field blank or responded “nothing.” However, some participants provided constructive criticism of the program. Of these participants, a number indicated that they would have appreciated more presenters sharing more stories, particularly stories relevant to their area of practice. Two participants who attended the same session expressed concern that the health care practitioners involved in the patients’ stories were not present to share their perspective on the events that transpired. However, this sentiment was not echoed elsewhere.

Interview Results: Impact on Storytellers

The storytellers involved in this curriculum reported the experience to be immensely rewarding and beneficial. When discussing their involvement, they emphasized the value of educating and connecting with audiences. However, storytellers also had to navigate an unpredictable emotional response to sharing. Although emotion could be a surprise, it could also be employed as a tool to make stories more meaningful for the audience. These three categories —education, connection, and emotion—are illustrated in the Sidebar: Experiences of Patient and Family Storytellers in Our Educational Curriculum, and described in detail here.

Experiences of Patient and Family Storytellers in Our Educational Curriculum.

These are representative transcript excerpts from participants within the following categories:

Educating participants

Communicating

“The one fundamental thing is just to introduce yourself when you go to see a patient. It’s so easy to say my name is Barb, or Susan, or Terry, or whatever it is, you know what I mean? Just introduce yourself to the patients.” (Storyteller 6)

Humanizing

“That’s a patient, that’s a person … not a file number or a chart number. Just listen to them, hold their hand, give them that smile. That’s all it takes. The nurses really pick up on it. They don’t realize how such a little gesture can mean so much to the patient.” (Storyteller 12)

Individualizing

“The goal of the story is showing them how it’s about connecting with the person, and treating the person like an individual. It’s respecting what gives them comfort.” (Storyteller 14)

Connecting with participants

“My story specifically relates to nurses, and I found it quite compelling the few times that I have told it to nurses. It involved them directly.” (Storyteller 11)

“My story, I think, allows people to experience their own lives, and [say], ‘That could have been me.’ I think that’s why it resonates with them because they’re part of the story.” (Storyteller 14)

“I had it be the case where there might be a facilitator who comments on the stories, and then it feels like, well, that’s what was said now. I think it’s really important to let the stories speak for themselves and let them resonate as they will with the audience. So that’s what good facilitation is; it’s kind of like being the conductor in the orchestra. He doesn’t make a sound; he doesn’t go and play the instruments for other people.” (Storyteller 5)

Navigating emotion

“It sometimes surprises me that I sometimes still get a little emotional, given the distance from most of what has happened to him (my sick child) and the number of times I’ve said it. But you know it always brings up different things at different times.” (Storyteller 9)

“It doesn’t matter if you’re nervous that you’re up there or you’re sad or angry or you’re teary-eyed or whatever else. Just be yourself. That hits the crowd the most when you’re yourself and not just a robot standing there, talking in a monotone voice for … however long you’re up there.” (Storyteller 19)

Educating Participants

Storytellers perceived the delivery of a number of valuable insights to the audience. By sharing their stories, they believed that they were educating health care professionals and driving change in the hospital culture. Different storytellers wished to convey different lessons to their audiences. Many storytellers wished to highlight the importance of communicating, or listening to patients and conveying salient information in a timely manner. Others stressed the importance of humanizing patients or seeing patients as people, not just as a diagnosis. Some storytellers hoped to convey the necessity of individualizing, or getting to know each patient and treating the patient as a unique individual. Although the educational objectives varied between storytellers and their stories, storytellers consistently reported a belief that their message was heard and education was achieved through the discussion of their stories.

Connecting with Participants

Storytellers connected with their audiences through involvement in the storytelling curriculum. When sharing, the relevance and relatability of a story were thought to be important in forging a relationship with the audience. Relevance encompassed the perceived appropriateness of narrative content and topic for an audience; for example, a story that prominently featured nurses and was shared with a nursing orientation audience. By contrast, a relatable story was thought to allow audience members to identify with the narrative and apply it to their own experiences; for example, a story about the death of a family member. Although relevance was predicated on audience interest, relatability touched audience experience and emotion. Depending on the storyteller, these tools could be used variably to engage the audience. Some storytellers also spoke about the role of the facilitator in helping set up a good connection with the participants for the discussion.

Navigating Emotion

Storytellers repeatedly spoke of the emotion that they were faced with throughout their health care experiences. Their encounters with illness, whether in the role of patient or caregiver, were reported to elicit a potent and often unsettling emotional response. When reflecting on their care, participants described this emotional response as being the most memorable aspect of their experience. This emotion translated into the storytelling experience and could resurface unexpectedly as storytellers shared in front of audiences. Emotion, although unpredictable, was also a tool for sharing poignant stories.

DISCUSSION

Feedback from participants has suggested there is a need to hear stories from diverse communities. The next phase to help advance compassionate care with our curriculum requires additional supports, resources, and tools addressing health equity. Future collaborations are being designed to address priority populations, including indigenous, immigrant, and refugee populations, patients with mental illness, and other diverse communities. The next phase of research, for which we have been granted financial support, will create a series of training tools and ways to engage that are considered best practices from patient and family experiences across a range of underserved populations.

Emerging from our experience of training patient storytellers was the learning that we also must train facilitators for these sessions. Although our survey and interview protocol did not ask about facilitation explicitly, storyteller interviews reported the important role of the facilitator, and our own anecdotal experience reinforces this insight. A well-prepared and skilled facilitator was reported by storytellers to be a source of comfort and confidence as the session unfolded. This individual must be able to create a safe environment in the curriculum to support open dialogue in a productive way—responsive to the person telling the story and his/her unpredictable emotion as well as to the audience receiving it. In particular, the facilitator played a crucial role in transitioning from patient stories to audience interaction. Going forward, we propose that facilitation be supported with formal training, just as we have supported storytelling. Those developing storytelling curricula must take care not to minimize the role of the facilitator and must not assume that health care practitioners come to the facilitator role with the necessary skills in place. The facilitator is a key contributor in the equation to ensure that both storytellers and health professional audiences are rewarded by their participation in the curriculum, and this role is certainly worthy of further exploration through future research endeavors.

CONCLUSION

We have described a patient storytelling preparatory workshop and educational storytelling sessions in a hospital curriculum to promote PFCC. This represents a novel contribution to the body of literature on engaging patients as teachers of PFCC. Although others have discussed guidelines for training patient and family storytellers,23,23 we offer a comprehensive 10-step workshop method for preparing and supporting storytellers in their role (Figure 1).

Furthermore, we explored the perceived impact of the curriculum on both storytellers and nurse audience members to further our understanding of the outcomes of patient engagement efforts. Both storytellers and audience members indicated that involvement in the curriculum was a positive experience. Patient stories were received by audience members and served to heighten their awareness of and appreciation for the provision of PFCC. Furthermore, patient and family storytellers perceived that they were educating and connecting with audience members. Although they were faced with an emotional response to storytelling that could be unexpected, their involvement was nevertheless described as rewarding.

The educational messages that storytellers described imparting to their audiences were reflected in audience responses regarding the impact of hearing patient stories. Storytellers aimed to teach lessons surrounding aspects of PFCC: Individualizing, humanizing, and communicating with patients. Audience participants indicated that they took away lessons that closely aligned with those dimensions, such as respecting “individual needs,” “treating patients as people,” and “introducing self.” As storytellers suggested, the curriculum forged a connection between health professionals, patients, and families, advancing health professionals from listeners to learners.

The finding that patient perspectives can be used to effectively teach lessons surrounding PFCC has been mirrored in other studies of patient engagement efforts.22–25 However, there is an emerging awareness that respectful patient engagement requires more than simply harnessing patient perspectives as a conduit for educational messages.26 The use of patient stories as “stand-alone vehicles” for organizational change risks fragmenting the patient from his/her own story and appropriating his/her perspective for unintended purposes.27–28 Given the unpredictable emotional response that storytellers face when sharing, considerate and supportive involvement is paramount to ensuring that the experience remains positive. Our storytelling workshop lays the foundation for sustainable patient engagement.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge AMS Healthcare: Advancing Education and Practice for the Phoenix Fellowship Grant making this work possible.

Kathleen Louden, ELS, of Louden Health Communications provided editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Pomey MP, Morin E, Neault C, et al. Patient advisors: How to implement a process for involvement at all levels of governance in a healthcare organization. Patient Experience Journal. 2016;3(2):99–112. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warren N. Involving patient and family advisors in the patient and family-centered care model. Medsurg Nurs. 2012 Jul-Aug;21(4):233–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson B, Abraham M, Conway J, et al. Partnering with patients and families to design a patient- and family-centered health care system: Recommendations and promising practices [Internet] Bethesda, MD: Institute for Family-Centered Care; 2008. Apr, [cited 2017 Oct 31]. Available from: www.hqontario.ca/Portals/0/modals/qi/en/processmap_pdfs/articles/partnering%20with%20patients%20and%20families%20to%20design%20a%20patient-%20and%20family-centered%20health%20care%20system.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bate P, Robert G. Experience-based design: From redesigning the system around the patient to co-designing services with the patient. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006 Oct;15(5):307–10. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.016527. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2005.016527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coulter A, Ellins J. Effectiveness of strategies for informing, educating, and involving patients. BMJ. 2007 Jul 7;335(7609):24–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39246.581169.80. DOI https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39246.581169.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Groene O. Patient centredness and quality improvement efforts in hospitals: Rationale, measurement, implementation. Int J Qual Health Care. 2011 Oct;23(5):531–7. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzr058. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzr058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilcock PM, Brown GC, Bateson J, Carver J, Machin S. Using patient stories to inspire quality improvement within the NHS Modernization Agency collaborative programmes. J Clin Nurs. 2003 May;12(3):422–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00780.x. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsianakas V, Robert G, Maben J, et al. Implementing patient-centred cancer care: Using experience-based co-design to improve patient experience in breast and lung cancer services. Support Care Cancer. 2012 Nov;20(11):2639–47. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1470-3. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1470-3. Erratum in: Support Care Cancer 2012 Nov;20(11):2649. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1567-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poochikian-Sarkissian S, Sidani S, Ferguson-Pare M, Doran D. Examining the relationship between patient-centred care and outcomes. Can J Neurosci Nurs. 2010;32(4):14–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Record JD, Rand C, Christmas C, et al. Reducing heart failure readmissions by teaching patient-centered care to internal medicine residents. Arch Intern Med. 2011 May 9;171(9):858–9. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.156. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2011.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pollack MM, Koch MA NIH-District of Columbia Neonatal Network. Association of outcomes with organizational characteristics of neonatal intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 2003 Jun;31(6):1620–9. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000063302.76602.86. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ccm.0000063302.76602.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000 Sep;49(9):796–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roter DL, Hall JA, Kern DE, Barker LR, Cole KA, Roca RP. Improving physicians’ interviewing skills and reducing patients’ emotional distress. A randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 1995 Sep 25;155(17):1877–84. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1995.00430170071009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jha V, Buckley H, Gabe R, et al. Patients as teachers: A randomised controlled trial on the use of personal stories of harm to raise awareness of patient safety for doctors in training. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015 Jan;24(1):21–30. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-002987. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2014-002987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charon R. Narrative medicine: Honouring the stories of illness. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stang AS, Wong BM. Patients teaching patient safety: The challenge of turning negative patient experiences into positive learning opportunities. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015 Jan;24(1):4–6. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003655. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tevendale F, Armstrong D. Using patient storytelling in nurse education. Nursing Times. 2015;111(6):15–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davidhizar R, Lonser G. Storytelling as a teaching technique. Nurse Educ. 2003 Sep-Oct;28(5):217–21. doi: 10.1097/00006223-200309000-00008. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00006223-200309000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Renard E, Alliot-Licht B, Gross O, Roger-Leroi V, Marchand C. Study of the impacts of patient educators on the course of basic sciences in dental studies. Eur J Dent Educ. 2015 Feb;19(1):31–7. doi: 10.1111/eje.12098. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/eje.12098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christiansen A. Storytelling and professional learning: A phenomenographic study of students’ experience of patient digital stories in nurse education. Nurse Educ Today. 2011 Apr;31(3):289–93. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2010.10.006. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Profiles of change [Internet] Bethesda, MD: Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care; 2013. [cited 2014 Mar 15]. Available from: www.ipfcc.org/profiles/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirk M, Tonkin E, Skirton H, McDonald K, Cope B, Morgan R. Storytellers as partners in developing a genetics education resource for health professionals. Nurse Educ Today. 2013 May;33(5):518–24. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2011.11.019. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2011.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morrise L, Stevens KJ. Training patient and family storytellers and patient and family faculty. Perm J. 2013 Summer;17(3):e142–5. doi: 10.7812/TPP/12-059. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/12-059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bokken L, Rethans JJ, van Heurn L, Duvivier R, Scherpbier A, van der Vleuten C. Students’ views on the use of real patients and simulated patients in undergraduate medical education. Acad Med. 2009 Jul;84(7):958–63. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a814a3. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0b013e3181a814a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Towle A, Godolphin W. Patients as educators: Interprofessional learning for patient-centred care. Med Teach. 2013;35(3):219–25. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.737966. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159x.2012.737966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oswald A, Czupryn J, Wiseman J, Snell L. Patient-centred education: What do students think? Med Educ. 2014 Feb;48(2):170–80. doi: 10.1111/medu.12287. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rowland P, McMillan S, McGillicuddy P, Richards J. What is “the patient perspective” in patient engagement programs? Implicit logics and parallels to feminist theories. Health (London) 2017 Jan;21(1):76–92. doi: 10.1177/1363459316644494. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459316644494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fancott CA. “Letting stories breathe”: Using patient stories for organizational learning and improvement [doctoral dissertation] Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto; 2016. [Google Scholar]