Abstract

Cicatricial pemphigoid (CP) is a chronic, autoimmune, subepidermal blistering disease with predominant mucosal involvement. In this article, we report a young patient with mucosal and extensive cutaneous involvement in the form of large erosions mimicking those of pemphigus vulgaris thus leading to diagnostic dilemma. We were unable to find any other previous reports with such extensive cutaneous erosions mimicking those of pemphigus vulgaris. Laminin 5 was the antigen found on knockout substrate testing. Antiepiligrin CP is a distinct subtype of CP with antibodies against laminin 5. This subtype is mostly associated with malignancy but no underlying malignancy was found in our case. Present report also highlights the importance of knockout substrate testing when immunoblot is not available.

Keywords: dermatology, skin

Background

Cicatricial pemphigoid (CP) also known as ‘mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP)’ is a chronic, recurrent, progressive, subepidermal blistering disorder which mainly affects the mucous membranes. Skin involvement is less common but in the present case there was extensive cutaneous involvement in the form of large erosions, which healed with scarring. Antilaminin 332 mucous MMP is a distinct subset of CP, which is seen in elderly and less commonly in the younger age group. Moreover, it is associated with underlying malignancy in two-third of patients. However, there are reports where no such association is found. Histopathology, direct, indirect immunofluorescence (DIF/IIF) and immunoblot help in making the diagnosis. But techniques like immunoblot are not easily available; therefore, knockout substrate testing can be helpful in making the correct diagnosis.

Case presentation

A 28-year-old man presented with recurrent painful erosions in oral cavity for last 2 years, erosions in the eyes along with diminution of vision for last 6 months and fluid filled blisters over body for last 5 months. Blisters used to rupture in 2–3 days to form raw erosions and used to heal with scarring in next 20–25 days. No other significant medical/social/family history was present.

Cutaneous examination revealed erosions varying in size from 2 to 15 cm in diameter with overlying reddish brown crusts over scalp, face, trunk, upper and lower limbs (figure 1). Examination of oral mucosa revealed erythematous, erosive lesions over lips, gingivae, buccal mucosae, soft palate and tongue (figure 2). Both eyes showed conjunctival congestion, erosions and symblepharon formation (figure 3). Nasopharyngeal examination could not be done as there was bleeding from the oral erosions. Both direct and indirect Nikolsky’s signs were negative. Systemic examination was within normal limits.

Figure 1.

Well-defined erosion of size 8–10×10–25 cm in size with adherent reddish brown crusts present over the upper chest.

Figure 2.

Bleeding erosions with adherent crusts present over lip extending to oral mucosa.

Figure 3.

Conjunctival congestion, erosion and symblepharon formation.

Investigations

Haematological, biochemical and radiological (chest X-ray, high-resolution CT chest, CT scan from neck to base of bladder, ultrasonography abdomen and prostate) investigations were normal. A biopsy from back was performed. Histopathological examination showed a partly ulcerated epidermis and subepidermal bulla formation. Intense fibrosis and inflammatory infiltrate comprising lymphocytes, eosinophils and polymorphs was noted in the blister base (figure 4). On DIF, an intense band of IgG and C3 was seen at the dermoepidermal junction (figure 5). IIF done on salt-split normal human skin as substrate with serum 1:10 stained with IgG showed a linear band of IgG along the floor of split (figure 6). IIF on antigen-deficient skin substrates showed positive reactions with the basement membrane zone (BMZ) on type VII collagen-deficient skin (figure 7) and negative findings on laminin 332-deficient skin (figure 8), leading to a diagnosis of antiepiligrin cicatricial pemphigoid (AECP).

Figure 4.

Histopathological examination showing ulcerated epidermis and subepidermal bulla with intense fibrosis and inflammatory infiltrate comprising lymphocytes, eosinophils and polymorphs in papillary dermis.

Figure 5.

Direct immunofluorescence showing intense dermoepidermal deposits of IgG and C3.

Figure 6.

Indirect immunofluorescence done on salt-split normal human skin as substrate with serum 1:10 and stained with IgG showing linear band of IgG along the floor of split.

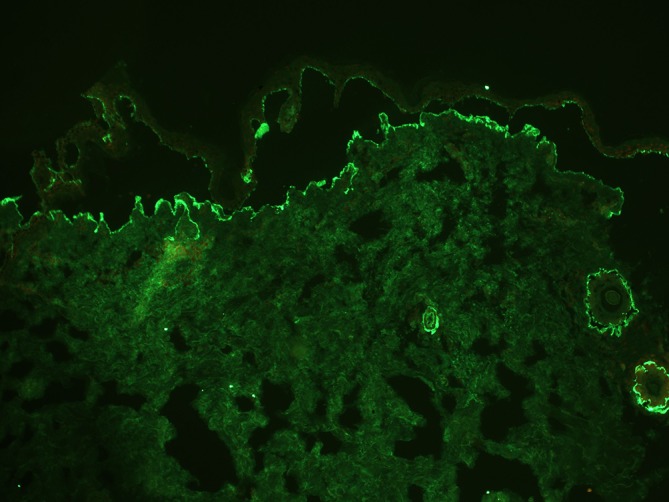

Figure 7.

Indirect immunofluorescence on antigen-deficient skin substrates showing positive reactions with the basement membrane zone on type VII collagen-deficient skin.

Figure 8.

Indirect immunofluorescence on antigen-deficient skin substrates showing negative findings on laminin 332-deficient skin.

Differential diagnosis

Pemphigus vulgaris, paraneoplastic pemphigus.

Treatment

The patient was started on oral deflazacort 90 mg and cyclophosphamide 50 mg daily. Methylcellulose drops were used for ocular lubrication. During active disease, tobramycin and cyclopentolate eye drops were given and 2 months later simple limbal epithelial transplant was done in right eye while amniotic membrane grafting was done in the left eye.

Outcome and follow-up

Cutaneous and mucosal lesions improved markedly in the follow-up done fortnightly for the patient. After 4 months, there was marked improvement in vision in the right eye while little improvement was seen in left eye.

Discussion

CP is one of the subepidermal blistering disorder targeting bullous pemphigoid (BP) 180 kD, BP 230 kD, laminin 332, type VII collagen and both subunits of α6β4 integrin.1 It is the disease of elderly (fifth–sixth decade) but can present in younger age group.2 Primarily affecting mucous membranes, the disease can involve skin in 25%–30% cases. Most common mucosa involved is oral followed by ocular, nasal, genital, laryngeal and oesophageal mucosae.1 Histopathologically subepidermal blistering is accompanied by predominant neutrophilic infiltrate and fibrosis. The diagnosis can further be confirmed by the presence of thin linear homogeneous deposits of IgG and C3 along the BMZ on DIF; this positivity is seen in around 80% cases. On salt-split examination, antibodies directed against BP180 and α6β4 integrin bind to the epidermal half, whereas antibodies directed against laminin 332 and type VII collagen bind to the dermal side of salt-split skin.1 3

Cutaneous lesions when present can mimick bullous pemphigoid but often there are lesions which heal with scarring.1 Our case had generalised erosions mimicking those of pemphigus vulgaris, which healed with scarring. We could find only six cases of CP with mucosal scarring and widespread bullous eruption reported previously.4 To the best of our knowledge, in none of the reported cases, the cutaneous lesions mimicked pemphigus vulgaris which makes our case different from others. Ocular mucosa is involved in around 80% of patients in the form of chronic cicatrising conjunctivitis, symblepharon, cicatricial entropion and trichiasis.1 5 There can be permanent vision loss in untreated cases. Conjunctival congestion, erosions and symblepharon formation were seen in the present case.

AECP, targeting laminin 332, is a subtype of CP which commonly affects elderly population but can be seen in young patients as seen in the present case.6 AECP is characterised by erosions and bullous lesions which typically heal with scarring. Ocular and oral mucosae are commonly involved; however, other mucosal sites like nasal, pharyngeal, laryngeal, oesophageal and genital region can also be involved. In the present case, there was extensive cutaneous involvement in the form of large spreading erosions which healed with scarring and makes the present case unique as cutaneous involvement is not a dominant feature of this condition.7 On DIF, intense deposits of IgG and C3 were present at the dermoepidermal junction, thus ruling out pemphigus vulgaris. IIF demonstrated thin linear band of IgG along the dermal side of the 1M NaCl split skin thus excluding bullous pemphigoid.7 AECP can be differentiated from epidermolysis bullosa accquisita (EBA) by IIF on antigen-deficient substrates (knockout substrate testing) of type VII collagen-deficient or laminin 332-deficient skin; if the antigen-deficient skin substrates show positive reaction on type VII collagen-deficient skin and negative reaction on laminin 332-deficient skin, it indicates that the patient’s serum contains antilaminin 332 autoantibodies and vice versa.

Patients with AECP have a high mortality rate than other immunobullous disorders because it is frequently associated with malignancies particularly visceral adenocarcinomas (lungs, stomach, colon and uterus) or lymphomas, usually within the first year after the onset of blisters. Laminin 5 is expressed by the malignant cells which associates it with the underlying cancers.7 Therefore, cancer screening is recommended in patients diagnosed with this subtype. But there are reports where no such association was found.8 In our case, also no such association was found. Investigations like ELISA, western immunoblotting, immunoprecipitation and immunuelectron microscopy, can confirm the diagnosis of different subepidermal immunobullous disorders.9 10 But they are often time consuming and expensive and also not easily available. Topical corticosteroids can be given in mild disease. Dapsone, corticosteroids, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil and cyclophosphamide1 are the first-line systemic medications in severe cases.

Unique findings of the present case are younger age of onset, extensive cutaneous involvement and detection of antiepiligrin antibodies without any association with malignancy. Also, our report highlights the importance of knockout substrate testing when immunoblot is not available.

Learning points.

Rarely extensive cutaneous involvement can be seen in cicatricial pemphigoid in addition to mucosal involvement.

It is a disease of middle age group but can be seen in young patients (first or second decade).

Histopathological examination, direct immunofluorescence, indirect immunofluorescence, western immunoblotting, immunoprecipitation and immunuelectron microscopy are helpful in confirming the diagnosis.

Patients with antiepiligrin cicatricial pemphigoid should be screened for any underlying malignancy.

Knockout substrate testing can support the diagnosis when immunoblot is not available.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors: conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version published. SS and SP: agreement to be accountable for the article and to ensure that all questions regarding the accuracy or integrity of the article are investigated and resolved.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Chan LS, Ahmed AR, Anhalt GJ, et al. The first international consensus on mucous membrane pemphigoid: definition, diagnostic criteria, pathogenic factors, medical treatment, and prognostic indicators. Arch Dermatol 2002;138:370–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kharfi M, Khaled A, Anane R, et al. Early onset childhood cicatricial pemphigoid: a case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol 2010;27:119–24. 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2009.01079.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kourosh AS, Yancey KB. Pathogenesis of mucous membrane pemphigoid. Dermatol Clin 2011;29:479–84. 10.1016/j.det.2011.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inaoki M, Ishii N, Hashimoto T, et al. Cicatricial pemphigoid with widespread bullous eruption. J Dermatol 2006;33:727–9. 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2006.00170.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mondino BJ, Brown SI, pemphigoid Ocicatricial. Ophthalmology 1981;88:95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Domloge-Hultsch N, Anhalt GJ, Gammon WR, et al. Antiepiligrin cicatricial pemphigoid. A subepithelial bullous disorder. Arch Dermatol 1994;130:1521–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egan CA, Lazarova Z, Darling TN, et al. Anti-epiligrin cicatricial pemphigoid: clinical findings, immunopathogenesis, and significant associations. Medicine 2003;82:177–86. 10.1097/01.md.0000076003.64510.00 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukushima S, Egawa K, Nishi H, et al. Two cases of anti-epiligrin cicatricial pemphigoid with and without associated malignancy. Acta Derm Venereol 2008;88:484–7. 10.2340/00015555-0506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vodegel RM, de Jong MC, Pas HH, et al. Anti-epiligrin cicatricial pemphigoid and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: differentiation by use of indirect immunofluorescence microscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;48:542–7. 10.1067/mjd.2003.99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen C-P, Plunkett R, Grover R, et al. Differentiating antiepiligrin cicatricial pemphigoid from epidermolysis bullosa acquisita by indirect immunofluorescence of skin substrates lacking Type VII collagen or laminin 332: a case report and review of literature. Dermatologica Sinica 2011;29:55–8. 10.1016/j.dsi.2011.05.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]