Abstract

Background:

Cancer of the bladder is the ninth leading cause of cancer in developed countries. It is the second most common urological malignancy. Transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) is the most common histological subtype in developed countries. In most of Africa, the most common type is squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Cancer of bladder guidelines produced by the European Urological Association and the American Urological Association, including the tumor, node, and metastasis staging is focused on TCC of the bladder.

Objectives:

The purpose of the study is to review the pathogenesis, pathology, presentation, and management of cancer of the bladder in Africa and to use this information to propose a practical staging system for SCC.

Methods:

The study used the meta-analysis guideline provided by PRISMA using bladder cancer in Africa as the key search word. The study collected articles available on PubMed as of July 2017, Africa Online and Africa Index Medicus. PRISMA guidelines were used to screen for full-length hospital-based articles on cancer of the bladder in Africa. These articles were analyzed under four subcategories which were pathogenesis, pathology, clinical presentation, and management. The information extracted was pooled and used to propose a practical staging system for use in African settings.

Results:

The result of evaluation of 821 articles yielded 23 full-length papers on hospital-based studies of cancer of the bladder in Africa. Cancer of the bladder in most of Africa is still predominantly SCC (53%–69%). There has been a notable increase in TCC in Africa (9%–41%). The pathogenesis is mostly schistosoma-related SCC presents late with painful hematuria and necroturia (20%). SCC responds poorly to chemotherapy or radiotherapy. The main management of SCC is open surgery. This review allowed for a practical organ-based stage of SCC of the bladder that can be used in Africa.

Conclusion:

Bladder cancer in Africa presents differently from that in developed countries. Guidelines on cancer of the bladder may need to take account of this to improve bladder cancer management in Africa.

Keywords: Africa, bladder carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, transitional cell carcinoma, Afrique, carcinome de la vessie, carcinome épidermoïde, carcinome à cellules transitionnelles

Résumé

Contexte:

Le cancer de la vessie est la neuvième cause de cancer dans les pays développés. C’est le deuxième plus fréquent urologique malignité. Le carcinome à cellules transitionnelles (TCC) est le sous-type histologique le plus commun dans les pays développés. Dans la majeure partie de l’Afrique, le plus le type commun est le carcinome épidermoïde (SCC). Lignes directrices sur le cancer de la vessie produites par l’Association européenne d’urologie et American Urological Association, y compris la tumeur, le nœud, et la mise en scène de la métastase est axée sur le TCC de la vessie.

Objectifs:

Le Le but de l’étude est d’examiner la pathogenèse, la pathologie, la présentation et la gestion du cancer de la vessie en Afrique et d’utiliser cette information pour proposer un système de mise en scène pratique pour SCC.

Méthodes:

L’étude a utilisé la ligne de méta-analyse fournie par PRISMA en utilisant le cancer de la vessie en Afrique comme le mot clé de recherche. L’étude a recueilli des articles disponibles sur PubMed à partir de juillet 2017, Africa Online et Africa Index Medicus. Les directives PRISMA ont été utilisées pour dépister des articles hospitaliers complets sur le cancer de la vessie en Afrique. Ces articles ont été analysés sous quatre sous-catégories qui étaient la pathogenèse, la pathologie, la présentation clinique et la gestion. le les informations extraites ont été regroupées et utilisées pour proposer un système de mise en scène pratique à utiliser dans les contextes africains.

Résultats:

Le résultat de l’évaluation sur 821 articles, 23 articles complets ont été publiés sur les études hospitalières sur le cancer de la vessie en Afrique. Cancer de la vessie dans la plupart des L’Afrique est toujours principalement SCC (53% -69%). Il y a eu une augmentation notable du TCC en Afrique (9% -41%). La pathogenèse est principalement la SCC liée au schistosome se manifeste tardivement par une hématurie douloureuse et une nécroturie (20%). SCC répond faiblement à la chimiothérapie ou la radiothérapie. La gestion principale de SCC est la chirurgie ouverte. Cette revue a permis un stade pratique de la CEC de la vessie qui peut être utilisé. en Afrique.

Conclusion:

Le cancer de la vessie en Afrique présente différemment de celui des pays développés. Lignes directrices sur le cancer de la vessie Il faudra peut-être en tenir compte pour améliorer la gestion du cancer de la vessie en Afrique.

INTRODUCTION

There is a 15-fold variation in the incidence of cancer internationally.[1,2] There is little written on cancer of the bladder in Africa in the literature. The predominant histological subtype of cancer of the bladder in developed countries is transitional cell carcinoma (TCC).[3,4,5] In much of Africa, the predominant subtype continues to be squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the bladder.[6,7] Most of the literature has focused on TCC of the bladder.[8,9] The staging and treatment guidelines focus almost exclusively on TCC.[10] Urologists and surgeons, practicing in Africa, are faced with the challenge of managing bladder cancer of SCC subtypes which presents in a different way from TCC. The aetiology of TCC is associated with working in the dye industry as well as smoking. On the other hand SCC occurs where countries have a high burden of Schistosomiasis. TCC is common in more industrialized countries while SCC is more common in less industrialized countries. The clinical presentation of TCC is mostly with painless hematuria, while in contrast, that of SCC presents with painful hematuria, bladder mass, and necroturia. Like most urological diseases in developing countries, SCC presents late to the urologist, when the disease is already advanced with muscular invasion.[11,12] In contrast, most TCC presents relatively earlier with only mucosal involvement. This may relate in part to better access to urology services and better cancer screening programs in developed countries.[13,14] The management of TCC is mostly by transurethral resection of bladder tumor and bladder instillation therapy. On the other hand, SCC is managed mostly by open surgery. The bladder cancer staging in wide usage is the tumor, node, and metastasis (TNM) staging, this is more suited to TCC rather than SCC. The reason, why this is the case, is that the staging guideline is specifically for TCC[15,16] (European Urological Association guidelines and AUA guidelines). In addition, the pathogenesis of TCC suggests the disease spreading layer by layer from the mucosa to the serosal layer or inward to outward.[17,18] In contrast, SCC with the schistosoma eggs implanted in the perivesical plexus; the pathology may be seen to spread in an opposite direction.[19,20]

METHODS

A meta-analysis was done using the PRISMA guidelines. All articles available on PubMed, African Index Medicus, and African Journals Online up to July 2017 for all available records to that date were searched. This was a simple search based on the default setting using the search phrase “Bladder Cancer in Africa.” The medical subject headings were used in the ordinary PubMed default mode as would be used by a routine researcher search in PubMed. The Boolean operations to combine terms and broaden the search were not used to avoid a wide nonspecific reach in the study area. A supplementary list of excluded papers is included in the supplementary data materials sent to the journal. The articles were reviewed for duplication and completeness. The inclusion criteria for articles in addition to the search term, where hospital-based studies, studies done in Africa, and publications with full articles available online. All articles that met these criteria were included in the study. The review looked at four subtopics under cancer of the bladder in Africa. These subtopics were pathogenesis, pathology, presentation, and management. These studies were pooled and entered into Epi Info 7.2.

RESULTS

There were 821 articles identified in the data search using the term “Bladder Cancer in Africa.” Using the PRISMA guidelines, 23 articles were included in the study. The PRISMA guide in Flow Chart 1 shows the process and Table 1 shows the articles identified through this search.

Flow Chart 1.

Cancer of the Bladder Meta-analysis outline

Table 1.

Bladder cancer studies in Africa

| Number | Country | Study type | n | Parameters | Source | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epidemiology | Pathology | Presentation | Management | |||||

| 1 | South Africa | Review | 59 publications | X | X | X | X | Heyns and van der Merwe CMF CJU, 2008[6] |

| 2 | South Africa | Cancer registry | 2500 patients | X | Sutherland, 1968[17] | |||

| 3 | South Africa | Hospital based | 650 | X | X | Groeneveld et al. BJU, 1996[31] | ||

| 4 | Zambia | Hospital based | 150 patients | X | X | - | - | Bowa et al. MJZ, 2008[30] |

| 5 | Zambia | Hospital based | 53 | X | X | X | - | Mapulanga et al. MJZ, 2012[32] |

| 6 | Zimbabwe | Cancer registry | 494 | X | X | Parkin et al. CEBP, 1994[18] | ||

| 7 | Zimbabwe | Hospital based | 483 | X | X | Thomas et al. JTHM, 1990[33] | ||

| 8 | Nigeria | Hospital based | 306 | X | X | X | X | Mandong et al. NJSR, 2000[19] |

| 9 | Nigeria | Hospital based | 30 | X | - | - | X | Alashan et al. AJU, 2007[13] |

| 10 | Nigeria | Hospital based | 89 | X | X | Ochicha et al. WAJM, 2003[20] | ||

| 11 | Tanzania | Hospital based | 120 | X | X | X | X | Ngowi et al. EACJ, 2015[21] |

| 12 | Kenya | Hospital based | 52 | X | Waihenya and Mungai EAJS, 2004[22] | |||

| 13 | Malawi | Hospital based | 200 | X | Mtonga et al. MJM, 2013[23] | |||

| 14 | Sudan | Hospital based | 106 | X | X | X | X | Husain and Shumo SJMS, 2008[24] |

| 15 | Uganda | Hospital based | 83 | X | Dodge, 1964[25] | |||

| 16 | Senegal | Hospital based | 428 | X | X | X | X | Diao et al. PIU, 2008[26] |

| 17 | Morocco | Hospital based | 43 | X | El Ochi et al. BMC, 2017[8] | |||

| 18 | Egypt | Review | 44 publications | X | X | X | X | Shokeir BJUI, 2004[7] |

| 19 | Egypt | Review | 70 publications | X | X | X | X | El-Sebaie et al. IJCO, 2005[11] |

| 20 | Egypt | Hospital based | 180 | X | X | X | X | Awwad et al., 2012[41] |

| 21 | Egypt | Review | 101 publications | X | X | X | X | Alashan et al. JENCI, 2007[13] |

| 22 | Egypt | Hospital based | 128 | X | X | X | X | Khalaf et al. AJU, 2008[10] |

| 23 | Ethiopia | Hospital based | 60 patients | X | X | Biluts and Minas EACJ, 2011[27] | ||

Pathogenesis

The review identified four key factors associated with bladder cancer in Africa. The key factors are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

The factors associated with bladder cancer pathogenesis in Africa

| SCC | TCC | Publication | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schistosomiasis | 29%-85% | 10% | Alashan et al.,[13] Waihenya and Mungai,[22] Groeneveld et al.,[31] Thomas et al.,[33] Heyns and van der Merwe,[6] Diao et al.,[26] Khalaf et al.[10] |

| Spinal injury | 2.5%-10% | Heyns and van der Merwe,[6] Shokeir[7] | |

| Smoking | 70% smoking in Egypt | 30%-60% | Waihenya and Mungai,[22] Ngowi et al.,[21] Thomas et al.[33] |

| Industrial chemicals | 27% | Heyns and van der Merwe,[6] Awwad et al.[41] |

SCC=Squamous cell carcinoma, TCC=Transitional cell carcinoma

Pathology

The review itemized the key aspects of the pathology of the bladder in Africa which highlighted the site, the shape, the size, the grade, the stage, and lymph node spread. This is shown in Table 3. In addition, Table 4 highlights the subtype and proportion by African country.

Table 3.

The pathology findings in cancer of the bladder in Africa

| SCC | TCC | Publication | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Site | Solitary, bladder fundus predominantly | Multifocal Bladder base predominantly | Alashan et al.,[13] Waihenya and Mungai,[22] Groeneveld et al.,[31] Thomas et al.[33] |

| Shape | Nodular or ulcerating 83% | Fern-like sessile | Shokeir[7] |

| Size | >3 cm | <3 cm | El-Sebaie et al.,[11] Heyns and van der Merwe,[6] Shokeir[7] |

| Grade | Grade 1 40-70% | Grade 2 and 3 69%-86% | Waihenya and Mungai,[22] Ngowi et al.,[21] Thomas et al.,[33] Khalaf et al.,[10] Heyns and van der Merwe,[6] Shokeir[7] |

| Stage | T3 and T4 Muscle invasive 90% | T1 and T2 Nonmuscle invasive 70%-76% | Heyns and van der Merwe,[6] Shokeir[7] |

| Lymph node spread | 2%-10% Late due to fibrosis | Early lymph node spread 17% | Khalaf et al.,[10] Heyns and van der Merwe,[6] Shokeir[7] |

SCC=Squamous cell carcinoma, TCC=Transitional cell carcinoma

Table 4.

The epidemiology of cancer of the bladder key subtypes in Africa countries

| SCC | TCC | Publication | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zambia | 71%-60% | 13% (1987) 30% (2011) | Bowa et al.,[30] Mapulanga et al.[32] |

| Senegal | 58% | 38% | Diao et al.[26] |

| Nigeria | 39%-66% | 26%-60% | Ochicha et al.,[20] Madong c et al.[19] Alhasan et al.[13] |

| Zimbabwe | 52%-71% | 21%-31% | Heyns and van der Merwe[6] |

| Tanzania | 18%-72% | 20%-75% | Heyns and van der Merwe,[6] Ngowi et al.,[21] Rambau et al.[28] |

| Egypt | 53% (1990) 23% (2000) | 23% (1990) 67% (2000) | Heyns and van der Merwe,[6] Kalaf et al.[10] |

| Kenya | 13% | 53%-67% | Heyns and van der Merwe[6] |

| South Africa (Africans) | 53% (blacks) | 30% (blacks) | Heyns and van der Merwe[6] |

| South Africa (White) | 2% | 95% | Heyns and van der Merwe[6] |

| South Africa (Asian) | 18% | 75% | Heyns and van der Merwe[6] |

| South Africa (Western cape) low schisto | 6% | 79% | Heyns and van der Merwe[6] |

| Ethiopia | 5% | 80% | Biluts and Minas[27] |

SCC=Squamous cell carcinoma, TCC=Transitional cell carcinoma

Presentation

Table 5 shows the clinical presentation of the patients based on age, sex, symptoms, and clinical stage.

Table 5.

Clinical presentation of cancer of the bladder patients in Africa

| SCC | TCC | Publication | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 45-65 | 65-75 | Bowa et al.,[30] Alashan et al.,[13] Waihenya and Mungai[22] Groenveld et al.,[31] Thomas et al.,[33] Mapulanga et al.[32] |

| Sex | 5-1 Ratio lower in Southern Africa, higher in North Africa |

2-1 | Kalaf et al.,[10] Heyns and van der Merwe,[6] Shokeir[7] |

| Symptoms | Painful Hematuria Necroturia 80%-95%, bladder mass 46% |

Painless Hematuria 90% |

Waihenya and Mungai,[22] Groeneveld et al.,[31] Thomas et al.,[33] Diao et al.[26] |

| Clinical stage | T2-T4 (MIBC) 60%-98% |

T1 (NMIBC) 49% |

Heyns and van der Merwe,[6] Ngowi et al.,[21] Rambau et al.,[28] Shokeir[7] |

SCC=Squamous Cell Carcinoma, TCC=Transitional Cell Carcinoma, MIBC=Muscle-invasive bladder cancer, NMIBC=Nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer

Management

Table 6 shows the management of each major subtype with the three key parameters of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy.

Table 6.

Management of cancer of the bladder in Africa

| SCC | TCC | Publication | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Open surgery (cystectomy, partial cystectomy or diversion) | 75%-50% 5 years survival | Uncommon | Waihenya and Mungai,[22] Groeneveld et al.,[31] Thomas et al.,[33], Diao et al.,[26] Alashan et al.[13] |

| Radiotherapy | Radioresistant | Radioresponsive | Heyns and van der Merwe,[6] Ngowi et al.,[21] Rambau et al.,[28] Shokeir[7] |

| Chemotherapy | Chemoresistant | 30%-60% | Waihenya and Mungai,[22] Groeneveld et al.,[31] Thomas et al.,[33] Diao et al.,[26] Alashan et al.[13] |

| TURBT (endoscopic) | 90% with 5 years survival | Shokeir,[7] Heyns and van der Merwe[6] | |

| Inoperable | 27% fixed tumor | Heyns and van der Merwe,[6] Diao et al.[26] |

SCC=Squamous cell carcinoma, TCC=Transitional cell carcinoma, TURBT=Transurethral resection of bladder tumor

DISCUSSION

The results show that SCC in Africa is still largely associated with schistosomiasis infection in up to 85% of cases. However, there is a changing pattern of SCC which is being influenced by smoking, industrialization, and schistosomiasis control.[21,22,23,24] It has been noted, particularly in Egypt, that there has been an increasing habit of smoking, which is associated with an increased risk of cancer of the bladder. With increased schistosoma control, industrialization, and westernized lifestyles, the relative proportions of SCC and TCC are changing in favor of TCC.[25,26,27] There are notable changes in the proportion of SCC and TCC across individual African countries. In particular in Tanzania, where regions which are close to inland freshwater lakes continue to have high relative proportions of SCC relative to areas further away.[28,29] In South Africa, they are marked differences across racial groups such as native populations, Asian, colored, and expatriate populations. In general, there appears to be a high proportion of SCC among native black population groups, where SCC is as high as 53%. In contrast among the Asian, colored, and white populations, SCC represents only 18%, 6%, and 2%. This may be related to genetic, social, and behavior factors.[28,29,30]

The pathology shows that SCC tends to be focally locate as an ulcerative and nodular mass in the bladder fundus. The mass being usually >3 cm in size at first presentation.[31,32,33] The SCC is also muscle invasive in 80% of cases at the time at first presentation.[34] In contrast, TCC tends to be multifocal small and papillary like with little or no muscle invasion at first presentation.[35] SCC also has a lower grade usually Grade 1 when patients are first seen in the hospital.[35] TCC on the other hand tends to be of Grade 2 or 3 at first presentation. TCC also spreads early to the lymph nodes, whereas SCC spreads late possibly due to fibrosis of the lymphatic channels caused by the schistosoma eggs.[35,36] In SCC, only in 2% to 10% is lymph node spread observed.[35,36] In clinical presentation, patient with SCC tends to be younger and male. In contrast, TCC has a higher proportion of females and presents in an older age group.[35,36] The most frequent clinical presentation of TCC is of painless hematuria, in a person older than 40 years of age. With SCC, the patient presents with painful hematuria associated with irritative symptoms, necroturia, or a bladder mass.[37,38] In relation to treatment, the two subtypes of cancer of the bladder tend to be treated very differently. Closed surgery by transurethral resection is most frequent mode in TCC, and this is supplemented by chemotherapy and radiotherapy depending on the tumor grade. On the other hand, SCC is generally radio- and chemoresistant. It is managed mainly by open surgery with partial or total cystectomy. TCC has a better 5-year survival of about 90% in 5 years compared to SCC which has a 5-year survival of close to 70%.[37,38,39] Up to 27% of SCC may be fixed and inoperable, especially if located below intraureteric bundle of Mercier.[38,39]

Staging

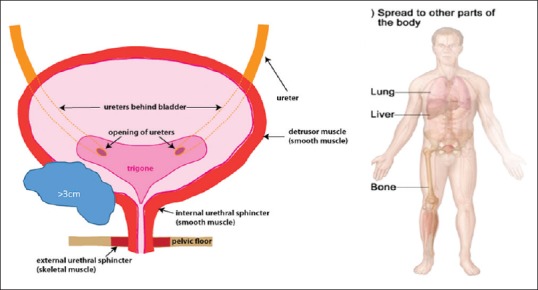

The differences in the pathogenesis, pathology, clinical presentation, and management between the two common subtypes of cancer of the bladder in Africa suggest that the approach to the two may need to be varied. In particular, while the TNM classification is well suited to the staging of TCC, it may not be as well suited to SCC. The TNM is a histological-based staging, which focuses on the luminal spread of the cancer across the bladder wall. This is better and easily applied to TCC. However, with SCC, an organ-based staging is more suitable of SCC. The Africa papers appear to suggest that SCC is locally invasive and spread along the bladder from the fundus to the bladder neck area.[38,39] Therefore, the staging instead of being transmural should be vertical from the fundus to the bladder neck. Box Chart 1 shows an organ-based staging, which follows the method of cancer spread. Figure 1 is a small cancer <3 cm confined to the bladder fundus. Figure 2 is cancer >3 cm without involvement of the ureters or the serosa. Figure 3 is cancer which has invaded either one or both ureters. Figure 4a is cancer which has invaded the serosa or the Trigone area of the Bladder. This cancer is only partially fixed. Figure 4b is cancer that has invaded the pelvic organs and is fixed. Figure 5 is distant metastasis.

Box Chart 1.

Cancer which has invaded the serosa. (a) With partial fixity. (b) With complete fixity

Figure 1.

Cancer <3 cm in longest width not invading the serosa (no fixity)

Figure 2.

Cancer >3 cm in longest diameter with ureteric invasion (hydronephrosis) (no fixity)

Figure 3.

Cancer <3 cm involving the trigone area not invading the serosa (no fixity)

Figure 4.

Cancer which has invaded the serosa. (a) With partial fixity. (b) With complete fixity

Figure 5.

Systemic disease

Most cases of bladder cancer in Sub-Saharan African countries are predominantly SCC subtype. In developed countries, on the other hand, SCC is uncommon while TCC represents over 90% of bladder cancer type. The main causes of bladder cancer in developed countries are smoking and industrial chemicals.

In many developing countries, however, there has been a notable increase in the proportion of TCC with the increase in industrialization. In spite of this change, SCC continues to be the predominant subtype in much of Sub-Saharan Africa. It occurs especially in predominantly high burdened schistosomiasis areas. It is proportionately a disease of men and presents at a mean age of 50 years. On the other hand, TCC presents a decade later with an almost equal male-to-female ratio. The SCC presents late with painful hematuria or other bladder symptoms. This is in contrast to TCC which presents earlier with painless hematuria and with minimal symptoms. In over 70% of cases, the bladder muscle wall is invaded at the time of presentation, while in TCC, over 90% of cases present with nonmuscle invasive disease. In practice, most urologists in Africa will use an organ-specific staging to plan for bladder cancer management due to this early muscular invasion.[40]

CONCLUSION

SCC has little or no pelvic node involvement at presentation. In contrast, TCC spreads early to pelvic nodes, once it has invaded the muscle wall. SCC is mostly radioresistant and does not respond to chemotherapy. TCC, on the other hand, shows a good response to radiotherapy, bacillus Calmette-Guérin or mitomycin instillation, and chemotherapy. This study proposes a simple practical organ-based staging based on current knowledge of SCC pathology in Africa.[41,42]

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ploeg M, Aben KK, Kiemeney LA. The present and future burden of urinary bladder cancer in the world. World J Urol. 2009;27:289–93. doi: 10.1007/s00345-009-0383-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.3rd ed. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2015. American Cancer Society. Global Cancer Facts & Figures. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chavan S, Bray F, Lortet-Tieulent J, Goodman M, Jemal A. International variations in bladder cancer incidence and mortality. Eur Urol. 2014;66:59–73. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Serretta V, Pomara G, Piazza F, Gange E. Pure squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder in western countries. Report on 19 consecutive cases. Eur Urol. 2000;37:85–9. doi: 10.1159/000020105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmadi M, Ranjbaran H, Amiri MM, Nozari J, Mirzajani MR, Azadbakht M, et al. Epidemiologic and socioeconomic status of bladder cancer in Mazandaran province, Northern Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:5053–6. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.10.5053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heyns CF, van der Merwe A. Bladder cancer in Africa. Can J Urol. 2008;15:3899–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shokeir AA. Squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder: Pathology, diagnosis and treatment. BJU Int. 2004;93:216–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2004.04588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El Ochi MR, Oukabli M, Bouaiti E, Chahdi H, Boudhas A, Allaoui M, et al. Expression of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 in bladder urothelial carcinoma. BMC Clin Pathol. 2017;17:3. doi: 10.1186/s12907-017-0046-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hassan TM, Al-Zahrani IH. Bladder cancer: Analysis of the 2004 WHO classification in conjunction with pathological and geographic variables. Afr J Urol. 2012;18:118–23. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khalaf I, El-Mallah E, Elsotouhi I, Abu-Zeid H, Elmeligy A. Pathologic pattern of invasive bladder carcinoma: Impact of schistosomiasissis. Afr J Urol. 2008;14:90–7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Sebaie M, Zaghloul MS, Howard G, Mokhtar A. Squamous cell carcinoma of the bilharzial and non-bilharzial urinary bladder: A review of etiological features, natural history, and management. Int J Clin Oncol. 2005;10:20–5. doi: 10.1007/s10147-004-0457-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raghavan D, Shipley WU, Garnick MB, Russell PJ, Richie JP. Biology and management of bladder cancer. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1129–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199004193221607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alashan SU, Abdullahi A, Sheshe AA, Mohammed ST, Edino ST, Aji S. A radical cystectomy for locally advanced cancer of the bladder in Kano, Nigeria. Afr J Urol. 2007;13:112–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Felix AS, Soliman AS, Khaled H, Zaghloul MS, Banerjee M, El-Baradie M, et al. The changing patterns of bladder cancer in Egypt over the past 26 years. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:421–9. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9104-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall MC, Chang SS, Dalbagni G, Pruthi RS, Seigne JD, Skinner EC, et al. Guideline for the management of nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer (stages Ta, T1, and Tis): 2007 update. J Urol. 2007;178:2314–30. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soloway M, Khoury S. 2nd ed. Vienna: ICUD-EAU; 2012. Bladder Cancer 2nd International Consultation on Bladder Cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutherland JC. Cancer in a mission hospital in South Africa. With emphasis on cancer of the cervix uteri, liver and urinary bladder. Cancer. 1968;22:372–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196808)22:2<372::aid-cncr2820220214>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parkin DM, Vizcaino AP, Skinner ME, Ndhlovu A. Cancer patterns and risk factors in the African population of Southwestern Zimbabwe, 1963-1977. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1994;3:537–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mandong BM, Iya D, Obekpa PO, Orkar KS. Urological tumours in Jos university teaching hospital, Jos, Nigeria. Niger J Surg Res. 2000;2:108–13. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ochicha O, Alhassan S, Mohammed AZ, Edino ST, Nwokedi EE. Bladder cancer in Kano – A histopathological review. West Afr J Med. 2003;22:202–4. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v22i3.27949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ngowi BN, Nyongole OV, Mbwambo JS, Mteta AK. Clinicopathological characteristics of urinary bladder cancer as seen at Kilimanjaro christian medical centre, Moshi-Tanzania. East Cent Afr J Surg. 2015;20:36–45. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waihenya CG, Mungai PN. Pattern of transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder as seen at Kenyatta national hospital, Nairobi. East Afr Med J. 2004;81:114–9. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v81i3.9138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mtonga P, Masamba L, Milner D, Shulman LN, Nyirenda R, Mwafulirwa K, et al. Biopsy case mix and diagnostic yield at a Malawian central hospital. Malawi Med J. 2013;25:62–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Husain NE, Shumo AL. Pattern and risk factors of urinary bladder neoplasms in Sudanese patients in Khartoum state. Sudan J Med Sci. 2008;3:211–8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dodge OG. Tumors of the bladder and urethra associated with urinary retention in Uganda Africans. Cancer. 1964;17:1433–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196411)17:11<1433::aid-cncr2820171110>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diao B, Amath T, Fall B, Fall PA, Diémé MJ, Steevy NN, et al. Bladder cancers in Senegal: Epidemiological, clinical and histological features. Prog Urol. 2008;18:445–8. doi: 10.1016/j.purol.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Biluts H, Minas E. Bladder tumours at Tikur Anbessa hospital in Ethiopia. East Cent Afr J Surg. 2011;16:10–19. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rambau PF, Chalya PL, Jackson K. Schistosomiasis and urinary bladder cancer in North Western Tanzania: A retrospective review of 185 patients. Infect Agent Cancer. 2013;8:19. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-8-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zyaambo C, Nzala SH, Babaniyi O, Songolo P, Funkhouser E, Siziya S. Distribution of cancers in Zambia: Evidence from the Zambia national cancer registry (1990–2009) J Public Health Epidemiol. 2013;5:95–100. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bowa K, Kachimba JS, Labib MA, Mudenda V, Chikwenya M. The changing pattern of urological cancers in Zambia. Med J Zambia. 2008;35:157–9. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Groeneveld AE, Marszalek WW, Heyns CF. Bladder cancer in various population groups in the greater Durban area of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Br J Urol. 1996;78:205–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1996.09310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mapulanga V, Labib M, Bowa K. Pattern of bladder cancer at university teaching hospital, Lusaka, Zambia in the era of HIV epidemic. Med J Zambia. 2012;39:22–6. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas JE, Bassett MT, Sigola LB, Taylor P. Relationship between bladder cancer incidence, schistosoma haematobium infection, and geographical region in Zimbabwe. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1990;84:551–3. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(90)90036-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohammed AZ, Edino ST, Ochicha O, Gwarzo AK, Samaila AA. Cancer in Nigeria: A 10-year analysis of the Kano cancer registry. Niger J Med. 2008;17:280–4. doi: 10.4314/njm.v17i3.37396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghoneim MA, el-Mekresh MM, el-Baz MA, el-Attar IA, Ashamallah A. Radical cystectomy for carcinoma of the bladder: Critical evaluation of the results in 1,026 cases. J Urol. 1997;158:393–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.El-Bolkainy MN, Mokhtar NM, Ghoneim MA, Hussein MH. The impact of schistosomiasis on the pathology of bladder carcinoma. Cancer. 1981;48:2643–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19811215)48:12<2643::aid-cncr2820481216>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zaghloul MS. Bladder cancer and schistosomiasis. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2012;24:151–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jnci.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin JW, Carballido EM, Ahmed A, Farhan B, Dutta R, Smith C, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder: Systematic review of clinical characteristics and therapeutic approaches. Arab J Urol. 2016;14:183–91. doi: 10.1016/j.aju.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prudnick C, Morley C, Shapiro R, Zaslau S. Squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder mimicking interstitial cystitis and voiding dysfunction. Case Rep Urol. 2013;2013:924918. doi: 10.1155/2013/924918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Izard JP, Siemens DR, Mackillop WJ, Wei X, Leveridge MJ, Berman DM, et al. Outcomes of squamous histology in bladder cancer: A population-based study. Urol Oncol. 2015;33:425.e7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Awwad H, El-Baki HA, El-Bolkainy N, Burgers M, El-Badawy S, Mansour M, et al. Pre-operative irradiation of T3-carcinoma in bilharzial bladder: A comparison between hyperfractionation and conventional fractionation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1979;5:787–94. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(79)90062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.El-Sebaie M, Zaghloul MS, Howard G, Mokhtar A. Squamous cell carcinoma of the bilharzial and non-bilharzial urinary bladder: A review of etiological features, natural history, and management. Int J Clin Oncol. 2005;10:20–5. doi: 10.1007/s10147-004-0457-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]