Significance

DNA replication complexes are often prematurely ejected from sites of DNA replication. Left unrepaired, this situation results in incomplete genome replication and cell death. All cells have therefore evolved “replication restart” mechanisms to reload the replicative machinery. This process is orchestrated by the PriA DNA helicase in bacteria. We describe the structural mechanism by which PriA recognizes and processes branched DNA replication forks. PriA binds to each arm of the replication fork and interaction with the parental DNA is shown to be particularly important for targeting PriA’s lagging strand-specific functions in vitro and in vivo. Our work provides mechanistic insights into how genome maintenance proteins recognize DNA replication forks and how they couple those interactions to strand-specific functions.

Keywords: DNA replication restart, DNA repair, X-ray crystallography, protein–DNA complex, cross-link mapping

Abstract

DNA replication restart, the essential process that reinitiates prematurely terminated genome replication reactions, relies on exquisitely specific recognition of abandoned DNA replication-fork structures. The PriA DNA helicase mediates this process in bacteria through mechanisms that remain poorly defined. We report the crystal structure of a PriA/replication-fork complex, which resolves leading-strand duplex DNA bound to the protein. Interaction with PriA unpairs one end of the DNA and sequesters the 3′-most nucleotide from the nascent leading strand into a conserved protein pocket. Cross-linking studies reveal a surface on the winged-helix domain of PriA that binds to parental duplex DNA. Deleting the winged-helix domain alters PriA’s structure-specific DNA unwinding properties and impairs its activity in vivo. Our observations lead to a model in which coordinated parental-, leading-, and lagging-strand DNA binding provide PriA with the structural specificity needed to act on abandoned DNA replication forks.

Premature termination of DNA replication is lethal in bacteria, if left unrepaired (1). These events are quite common, however, arising from collisions between DNA replication complexes (replisomes) and damaged DNA or protein barriers (1, 2). Cell survival therefore depends on frequent replication reinitiation at abandoned DNA replication forks to complete genome synthesis, a process referred to as “replication restart” (3). Unlike canonical replication initiation, which relies on sequence-specific binding to origins of replication, replication restart is initiated by structure-specific recognition of abandoned DNA replication forks. Given the low abundance of such structures within genomic DNA, the proteins that drive replication restart have evolved to distinguish between replication forks and other DNA structures with high fidelity to avoid initiating unwarranted replication reactions. The physical mechanisms that allow replication restart proteins to operate exclusively at replication forks remain poorly defined.

Replication restart is facilitated in bacteria by the PriA DNA helicase. The process begins with PriA binding to abandoned replication-fork structures with high affinity. These substrates include replication forks with ds leading and lagging strands as well as those with ssDNA gaps on either or both strands (3). Interestingly, PriA can also bind to ssDNA and dsDNA with high affinity, although these binding events do not lead to replication restart (4–7). How PriA distinguishes between replication forks and other DNA structures remains unknown. Once bound, PriA remodels the lagging-strand arm to expose ssDNA, which is thought to provide a loading site for the replicative DNA helicase (DnaB in gram-negative bacteria) (8, 9). This remodeling occurs via 3′-5′ DNA unwinding when the lagging-strand arm is dsDNA. Alternatively, when the lagging-strand arm is ssDNA and bound by ssDNA-binding proteins (SSBs), PriA directly interacts with and remodels SSB/DNA complexes to expose ssDNA (9). PriA lagging-strand-specific activities are guided, in part, by other proteins present at the fork (SSB or RecG) and by the presence of a nascent leading strand near the replication-fork junction (8, 10). Targeting of PriA activities to the lagging strand is also facilitated by intrinsic PriA/DNA interaction mechanisms that orient PriA binding on DNA forks. However, structures of PriA/DNA replication-fork complexes have not been resolved and the lack of informative PriA variants has precluded cellular studies to probe possible roles of PriA/DNA interactions in vivo. DNA remodeling is followed by assembly of a “primosome,” which can include PriB, DnaT, and/or PriC proteins (3). The primosome then loads the DnaB helicase onto the parental lagging strand and DnaB recruits the rest of the replisome. PriA binding blocks access to the nascent leading strand until replicative helicase loading is complete (11–13).

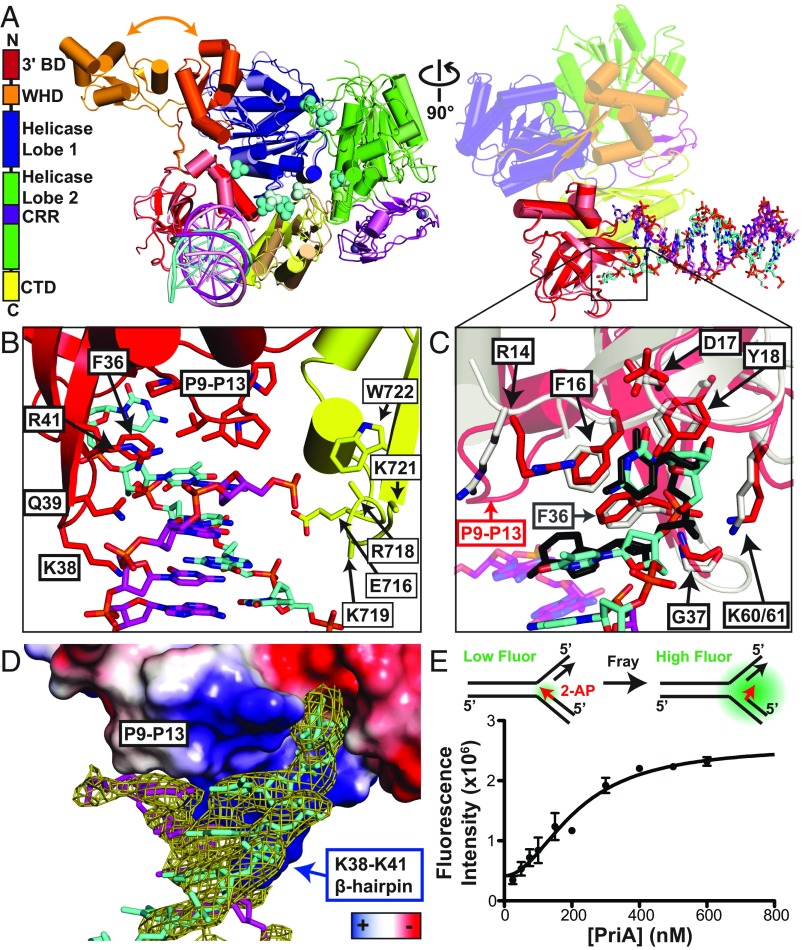

The crystal structure of PriA from Klebsiella pneumoniae (KpPriA) revealed a multidomain arrangement in which several DNA-binding domains are arrayed around the central helicase core (Fig. 1A). Although the DNA-binding activities of PriA domains have been examined in isolation, the mechanisms that confer structure-specific binding to abandoned DNA replication forks have not been well defined. The N-terminal-most domain of PriA [3′ binding domain (3′BD)] associates with the nascent leading strand and crystal structures revealed the presence of a nucleotide-binding pocket in the domain (14, 15). A linker connects the 3′BD to a circularly permuted winged-helix domain (WHD) that can bind DNA in isolation (16). The central portion of PriA is composed of its bilobed helicase domain. In the context of full-length PriA, the helicase domain preferentially unwinds the lagging strand at DNA replication forks that include a nascent leading strand or SSB (8). A Zn2+-binding cysteine-rich region is embedded within the helicase domain and is thought to serve a role in DNA unwinding (17). Finally, the C-terminal domain (CTD) can bind ssDNA, dsDNA, and forked DNA in isolation (9). A PriA interaction with parental duplex is anticipated from footprinting studies (10, 16, 18, 19) but it is not known which domain forms this interface and the role of a parental DNA interface in replication restart remains undefined.

Fig. 1.

Structure of PriA/DNA replication-fork complex resolves the dsDNA leading-arm interaction mechanism. (A, Left) Domain architecture and structure of K. pneumoniae PriA-dsDNA. (A, Middle) The two molecules from the asymmetric unit have been superimposed. Molecule A is in the bright colors used in the domain architecture diagram to the left and molecule B is in pale versions of those colors. Nascent leading strand (cyan) and parental leading strand (magenta) are shown as cartoons. Zinc atoms (gray) and sulfates (cyan) are shown as spheres. The orange arrow points to the two different locations of the WHD in molecule A and molecule B. (A, Right) Rotation for a side view of the 3′BD interaction with DNA from both PriA molecules in the asymmetric unit. The 3′BD and DNA from molecule A are in bright colors and from molecule B in pale colors, as in A, Middle. DNA is shown in sticks. The remaining PriA domains are shown in transparent cartoon and are those from molecule A. See also SI Appendix, Fig. S1 and Table S2. (B) Close-up view of the dsDNA interactions of the 3′BD and CTD of molecule A. K718, K719, and K721 side chains did not have sufficient electron density for modeling. (C) Close-up view of the 3′OH-terminal nucleotide binding pocket superimposed with the dinucleotide-bound EcPriA 3′BD structure [gray protein and black nucleotides (14)]. Residues involved in terminal nucleotide coordination are labeled in black. (D) Surface electrostatics view of the 3′BD with dsDNA Fo − Fc omit map contoured at 3.0σ. (E) Solution equilibrium DNA fraying analysis using 2-AP fluorescent base analog placed at the terminal base in the nascent leading strand. Data are mean ± SD (error bars) of three replicates.

In this study, structural, biochemical, and genetic approaches are combined to define the physical mechanisms and cellular roles of PriA/replication-fork interfaces. We report the 2.8-Å-resolution crystal structure of KpPriA in complex with a synthetic DNA replication fork. This structure reveals leading-strand dsDNA bound between the 3′BD and CTD and shows that binding to PriA unpairs and sequesters the 3′ end of the nascent leading strand in a conserved PriA pocket. Using a cross-linking method previously developed to map PriA interfaces with the lagging strand (20), an interaction between the WHD of Escherichia coli PriA (EcPriA) and parental duplex is identified. The WHD is shown to be critical for directing PriA unwinding of lagging-strand DNA and for preventing parental duplex unwinding on replication forks lacking a nascent leading strand. The WHD is also required for PriA activity in the PriA–PriC replication restart pathway and is important for DNA damage resistance in recG-null E. coli strains. Taken together these results define a physical model of PriA bound to replication-fork DNA and illustrate the consequences of dysregulated PriA replication-fork binding in vitro and in vivo.

Results

Structure of PriA/DNA Replication-Fork Complex Resolves the dsDNA Leading-Arm Interaction Mechanism.

Although bacterial PriA DNA helicases can bind to a variety of DNA structures, PriA initiates DNA replication processes only at abandoned DNA replication forks. To better understand how PriA engages replication forks, we carried out crystallization trials using PriA proteins from several bacterial species bound to a variety of replication-fork substrates. Diffracting crystals of KpPriA (88% identical and 94% similar to EcPriA) formed in the presence of a synthetic DNA fork composed of two partially complementary oligonucleotide parental strands annealed with a nascent leading-strand oligonucleotide (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A and Table S1). Crystal formation was dependent on the length and overhanging ends of the leading arm and parental duplexes but was independent of lagging-arm length from 5 to 17 nt. The 2.8-Å-resolution structure of DNA-bound KpPriA was determined by molecular replacement using the apo KpPriA structure (9) as a search model (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Table S2).

The KpPriA/DNA structure contained two PriA molecules per asymmetric unit with electron density for dsDNA extending from both PriA 3′BDs (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). The dsDNA sequence of the leading strand fit the best-resolved portion of the DNA electron density, particularly for nucleotides bound by the 3′BD. Continuous electron density for the parental and lagging-strand arms of the DNA was not observed, although a number of discontinuous peaks that were insufficient for structural modeling were observed along the surface of the PriA helicase domain. It is likely that the parental and lagging arms were not stably bound to PriA due to high salt crystallization conditions (1 M sulfate salts).

Examination of the resolved PriA/dsDNA interface showed that hydrogen bonding between the terminal two base pairs at the fork junction was disrupted, with the terminal bases physically separated by the 3′BD and the penultimate bases distorted from ideal bonding distances and angles (Fig. 1). A β-hairpin hydrophobic loop (P9–P13) was wedged between the unpaired/frayed bases and positioned ∼3.5 Å above the penultimate destabilized base pair (Fig. 1B). A second β-hairpin packed into the side of the dsDNA, with R41, Q39, and K38 extending toward the backbone of the template leading strand and F36 stacking above the penultimate nucleotide in the nascent leading strand. The PriA CTD also appeared to be in a position to assist in binding the leading-strand DNA, with residues E716, R718, and K719 near the backbone of the nascent leading strand and K721 and W722 near the frayed template strand. However, the side chains for residues R718, K719, and K721 were not resolved (Fig. 1B). The high-salt crystallization conditions may have prevented stable interactions between these residues and the DNA. Interestingly, published structures of the isolated E. coli PriA 3′BD bound to dinucleotides (14) superimposed closely with the 3′BD and terminal two nascent leading nucleotides in the PriA/DNA structure. Terminal nucleotide coordination by R14, F16, D17, Y18, G37, and K61 form a conserved 3′OH nucleotide-binding pocket that interacts with phosphodiester, ribose ring, and base (Fig. 1C and SI Appendix, Fig. S1B).

PriA molecules within the asymmetric unit were highly similar to each other and to apo KpPriA with the exception of the WHD [excluding WHDs, rmsds were 1.9 Å (molecule A versus B) and 1.4 Å (molecule A versus apo) for Cα atoms]. Comparison of the positions of WHDs from PriA molecules in the PriA/DNA structure along with the apo KpPriA structure revealed three different domain locations, with the apo KpPriA WHD located between the former two shown in Fig. 1A. In each case, the WHD packs against a symmetrically related PriA molecule within the crystal lattice. Thus, the WHD is likely quite mobile relative to the rest of PriA.

Fraying of the Leading Strand Is Part of the PriA/DNA Fork Interaction Mechanism.

Fraying of the leading strand in the crystal structure was unexpected, since PriA does not unwind this strand in helicase assays on DNA forks of this type (8). We hypothesized that these base pairs are frayed through the PriA DNA fork binding event, independent of PriA’s ATP-dependent helicase activity. To test whether fraying also occurs in solution within the PriA/DNA fork complex, we created a replication-fork substrate that placed the fluorescent base analog 2-aminopurine (2-AP) at the 3′ end of the nascent leading strand (Fig. 1E) and added PriA in the absence of ATP; 2-AP fluorescence is quenched when base-paired and stacked. Consistent with PriA fraying the 3′ end in solution, fluorescence of the 2-AP substrate increased with the addition of EcPriA. The PriA-induced fluorescence plateaued at levels equal to that observed with PriA incubated with either the 2-AP–containing oligonucleotide alone or an unquenched DNA fork control in which the template leading strand was not complementary to the 2-AP–containing oligonucleotide end. Thus, PriA binding appears to fray the leading-strand end in solution. This interaction allows PriA to sequester the 3′ end into a protein pocket, which could be important for the role of PriA in preventing access to the 3′ end until after replication restart is complete (11–13).

Protein/DNA Fork Cross-Linking Maps a PriA WHD Interface with the Parental Duplex.

Nuclease protection studies have shown that PriA binding protects each branch of a DNA replication fork, including ∼22 bp of the parental arm (16, 18). Given that the 3′BD and CTD bind the leading-strand arm (Fig. 1) and our prior mapping showed that the helicase domain binds the lagging-strand arm and the fork branch site (20), we hypothesized that the WHD could be the primary domain that associates with the parental arm. To test this model, we incorporated the photocross-linkable amino acid p-benzoyl-l-phenylalanine (Bpa) at several positions within the WHD of full-length EcPriA and assayed for formation of PriA/DNA cross-links with replication-fork DNA in vitro. A total of 13 PriABpa single-site variants were constructed, using the positions of DNA or RNA binding surfaces in other WHDs as guides (Fig. 2A displays a subset of the structures used to guide variant design). All purified Bpa variants bound the DNA fork with near wild-type EcPriA affinities (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). Cross-linking was performed by incubating PriA variants with a synthetic DNA replication fork under conditions that favor 1:1 PriA:DNA binding and exposing the complexes to UV light to photoactivate Bpa, which forms cross-links to nearby C–H bonds (21). Covalent PriA/DNA cross-links were observed with four variants: R134Bpa, P136Bpa, Q138Bpa, and A167Bpa. These reactive PriA WHD residues cluster to a single conserved surface of the domain that aligns well with WHD/DNA interfaces observed in the OhrR/ and HNF-3/DNA complex structures (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S2C) (22, 23). Analyses using substrates with different strands radiolabeled showed that each of the PriA variants cross-linked to the parental lagging and/or leading strands (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B). The addition of ADP appeared to enhance the efficiency of P136Bpa, Q138Bpa, and A167Bpa cross-links.

Fig. 2.

PriA/DNA cross-linking maps a PriA WHD interface with the parental duplex. (A) PriA WHD (wheat) with dsDNA from the cocrystal structures of OhrR (gray, ref. 22) and HNF-3 (black, ref. 23), where the WH domains of the three proteins were structurally superimposed. The four positions where Bpa incorporation yielded EcPriA DNA fork cross-links are labeled (EcPriA residue/KpPriA residue) and shown in sticks from the KpPriA apo structure (9). (B) Diagram of PE assay using 32P-5′-labeled primers (red arrows) annealed to either the parental leading or lagging strand within the cross-linking DNA fork (SI Appendix, Table S1). Red dotted line depicts PE, with “X” representing a block to PE by a covalent protein/DNA cross-link. (C) Sequence of the cross-linking DNA fork, with significant PE blocked products marked by dotted lines from the cross-linked Bpa site. Number marks indicate the length of the PE product for either parental lagging or leading PE. (D) Urea PAGE of PE on cross-linked parental lagging strand samples with sequencing ladder (right: T, C, A, and G labels indicate ddA, ddG, ddT, or ddC, respectively, was added). Red lines highlight significant PE bands not present in the negative control (lane 2). (E) Primer 2 for the parental leading strand and sequencing ladder as in D. Representative gels of at least three replicates. See also SI Appendix, Fig. S2.

The cross-linked samples were further analyzed by radiolabeled primer extension (PE) to map cross-linked sites on the DNA stands as previously described (20, 24) (Fig. 2B). Prematurely halted PE products mark cross-linked sites and the dominant bands for each variant that were present at significant levels above the negative control, across at least three replicates, were mapped onto the strand of interest by comparing the band migration to sequencing lanes for the strand (Fig. 2 C–E). PE experiments using the established PriA helicase domain E492Bpa variant were carried out alongside to confirm helicase core contacts were maintained as reported previously (20). UV-dependent R134Bpa, P136Bpa, Q138Bpa, and A167Bpa PE products were mapped to both parental strands at multiple sites 11–24 bp upstream from the replication-fork junction (Fig. 2 C–E). The observed cross-link locations on the DNA agree remarkably well with previous nuclease protection experiments (16, 18), strongly supporting a direct PriA WHD/parental arm interface.

The PriA WHD Is Not Required for PriA/DNA Replication-Fork Interaction in Vitro.

To examine biochemical roles for the WHD, an EcPriA variant lacking the WHD (EcPriA ∆WHD) and the isolated EcPriA WHD were produced recombinantly and purified. In contrast to wild-type EcPriA, EcPriA ∆WHD crystallized readily. The variant structure was determined to 1.98-Å resolution (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 and Table S2), revealing a structure that was very similar to apo KpPriA (rmsd 1.3 Å). Thus, deletion of the WHD did not disrupt the overall fold of the remainder of PriA.

To measure the impact of the PriA WHD on DNA binding, the equilibrium DNA-binding properties of EcPriA ∆WHD and the isolated EcPriA WHD were examined using a fluorescence anisotropy DNA-binding assay. EcPriA ∆WHD bound to two-stranded forked DNA, dsDNA, and ssDNA with high apparent affinities that were near those observed for EcPriA (Fig. 3). The isolated WHD interacted with each DNA with very low affinity and without structure specificity. These experiments failed to identify a primary role for the WHD in stable DNA binding under the conditions tested. To further analyze the kinetics of EcPriA and EcPriA ∆WHD DNA fork binding, we measured their dissociation rates from the DNA fork. Kinetic competition experiments revealed biphasic dissociation kinetics for both proteins with a greater percentage of EcPriA ∆WHD rapidly dissociating from a fork relative to EcPriA (SI Appendix, Fig. S4), which may indicate that the WHD plays a minor role in securing PriA to replication-fork DNA. Thus, deletion of the WHD had only modest effects on PriA DNA binding.

Fig. 3.

The PriA WHD is not required for PriA/DNA replication-fork interaction in vitro. Fluorescence anisotropy of a fluorescein-labeled DNA substrate [forked (Top), ds (Middle), or ss (Bottom) DNA (SI Appendix, Table S1)] measured with increasing PriA concentrations. Data are mean ± SD and fit to a single-site-specific model. Dissociation constants from fit are listed (right box). See also SI Appendix, Fig. S4.

The WHD Is Required for Orienting PriA on DNA Forks Lacking a Nascent Leading Strand in Vitro.

Since the WHD/DNA interaction was not a major stabilizer of the PriA/DNA complex, we next considered whether the domain could instead be important for directing structure-specific helicase functions. EcPriA has a noted specificity for unwinding the lagging strand at DNA replication forks (8). Interestingly, this specificity relies on the presence of either the 3′ end of a nascent leading strand near the replication-fork junction or an interaction partner such as SSB for proper orientation. In the absence of both, EcPriA 3′-5′ helicase activity can unwind both lagging-strand and parental DNA duplexes at replication forks (8). EcPriA and EcPriA ∆WHD helicase activities were measured for a variety of replication-fork structures using a gel-based DNA unwinding assay to test whether the WHD plays a role in structure-specific DNA unwinding. Consistent with such a role, EcPriA and EcPriA ∆WHD differed significantly in the assay (Fig. 4). On a three-stranded DNA fork that included a nascent lagging strand but lacked a nascent leading strand and in the presence of SSB, EcPriA specifically unwound the lagging strand whereas EcPriA ∆WHD unwound the parental duplex and the lagging strand without preference (Fig. 4A). EcPriA ∆WHD also appeared to be less efficient than EcPriA, converting less substrate into product at low enzyme concentrations. We noted that EcPriA has reduced helicase activity at concentrations above 5 nM due to DNA reannealing or autoinhibition (Fig. 4), as has been observed previously (20). EcPriA ∆WHD helicase activity was not impaired at high enzyme concentrations. Concentration-dependent inhibition of EcPriA may be linked to formation of higher-order PriA complexes on DNA that were observed with EcPriA but not EcPriA ∆WHD in electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). In the absence of SSB, EcPriA unwinding activity was still primarily directed to the lagging strand at low enzyme concentrations, with some parental duplex unwinding observed at higher PriA concentrations. With this substrate, time-resolved helicase assays showed that EcPriA first unwound the lagging strand and then unwound the parental duplex (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B). In the absence of SSB, EcPriA ∆WHD predominantly targeted the parental duplex, with minimal unwinding of the lagging strand observed at any concentration or time point tested.

Fig. 4.

The WHD is required for orienting PriA on DNA forks lacking a nascent leading strand in vitro. (A) PAGE of helicase products from increasing concentrations of PriA (0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, 10, and 50 nM) added to a three-stranded 32P-5′-labeled synthetic DNA fork type depicted between gel panels in black (1 nM; see SI Appendix, Table S1), where stars indicates the site of the 32P-5′ label. Helicase products are depicted in gray. Left gel panels: SSB (62.5 nM, tetramers) was preincubated with the DNA fork. Right gel panels: SSB was omitted. (B) Two-strand DNA fork type assessed as in A. (C) Four-strand DNA fork type assessed as in A and B. Gels are representative of at least three replicates. See also SI Appendix, Figs. S4 and S5.

With a two-stranded replication fork that only contained duplex parental strands and in the presence of SSB, EcPriA ∆WHD displayed similarly dysfunctional activity, unwinding the parental duplex under conditions in which EcPriA did not (Fig. 4B). In the absence of SSB, both EcPriA and EcPriA ∆WHD unwound parental duplex with similar efficiencies.

Interestingly, on a four-stranded replication fork (nascent leading and lagging strands present), both EcPriA and EcPriA ∆WHD unwound the lagging strand with similar efficiencies and specificities (Fig. 4C and SI Appendix, Fig. S5C). SSB stimulation of PriA helicase activity was observed for both EcPriA and EcPriA ∆WHD. The similar activity of EcPriA and EcPriA ∆WHD on this substrate is consistent with the 3′BD/leading-strand interaction helping to bias PriA helicase activity toward lagging-strand unwinding (8). Thus, these studies show that the PriA WHD is not required for helicase activity but that, with substrates lacking a nascent leading strand, the PriA WHD and the presence of SSB are both required for proper PriA/DNA fork interaction and orientation.

EcPriA ∆WHD Helicase Specificity Dysfunction Selectively Inactivates the PriA–PriC Replication Restart Pathway in Vivo.

The altered structure specificity of EcPriA ∆WHD helicase activity suggested that the variant could be used as a tool for investigating the impact of dysfunctional PriA activity on cellular replication restart reactions. To this end, an E. coli priA mutation was generated in which codons for residues 114–174 were deleted from the chromosomal priA gene such that it encoded EcPriA ∆WHD (priA∆WHD). The priA∆WHD allele was combined with sulA-gfp and hupA::mcherry chromosomal reporter fusions that enable quantification of the SOS DNA-damage response and visualization of nucleoids, respectively, without killing cells (25–27). The strains also carried the sulB103 allele of ftsZ, which is often used in priA mutant analysis to prevent the action of sulA, an SOS-induced cell division inhibitor (25, 28).

The priA∆WHD strain was strikingly similar to the priA+ parent strain (Fig. 5). The level of SOS induction and measured cell areas were indistinguishable and the nucleoid structures of both stains displayed normal morphologies. In contrast, a priA-null (priA2::kan) strain was induced for SOS and had elongated cells (distinguishable by an increase in cell area) and irregular nucleoid structures that are observed with chromosome partitioning defects (Par−) (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). Additionally, both the priA+ and priA∆WHD strains displayed similar resistance to DNA-damaging UV light (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

EcPriA ∆WHD helicase specificity dysfunction selectively inactivates the PriA–PriC replication restart pathway in vivo. (A) Phase contrast (Left), GFP fluorescence (Middle; measure of SOS induction levels through sulA-gfp fusion), and mCherry fluorescence (Right; visualization of nucleoids through hupA::mcherry fusion) microscopy images of E. coli. (Scale bars, 10 μm.) (B) Quantification from images as in A for mutants used in this study (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 and Table S3). The Par− phenotype was defined by cells containing multiple poorly condensed nucleoids as assessed by the visualization of nucleoids. GFP relative fluorescence intensity (RFI) was a measure for SOS induction and generated by taking at least three different images of cells on three different days.

Fig. 6.

priA∆WHD-containing strains exacerbate the UV sensitivity of recG-null strains. priA and priA mutant effects on UV sensitivity of recG-null strains (SI Appendix, Table S3). Surviving fraction after exposure to increasing levels of UV (0, 40, 60, and 80 J/m2). Data are means of four replicates ±SD. **P < 0.01 between indicated point and recG::kan alone.

Since multiple PriA-dependent replication restart pathways are present in E. coli (PriA–PriB and PriA–PriC pathways) and each has different PriA activity requirements, we created double mutants to analyze the impact of removing the PriA WHD in the PriA–PriB pathway (priA∆WHD priC::kan) and in the PriA–PriC pathway (priA∆WHD ∆priB). The priA∆WHD priC::kan mutant was indistinguishable from the single priC::kan strain, indicating that EcPriA ∆WHD retains the PriA activities required to support the PriA–PriB pathway (Fig. 5 and SI Appendix, Fig. S6). In contrast, the priA∆WHD ∆priB strain was induced for SOS and displayed an increased cell length compared with either single-mutant strain (6.6-fold increase in RFI and 2.2-fold increase in cell area, compared with the priA+ ∆priB strain). In addition, the nucleoids of priA∆WHD ∆priB cells exhibited partition defects (Fig. 5). These phenotypes were comparable to what is observed in a priA-null mutant (Fig. 5B and SI Appendix, Fig. S6), indicating that EcPriA ∆WHD lacks the PriA activities required for the PriA–PriC pathway. A similar phenotype has been seen for priA300, which encodes for a PriA variant with an ATPase active site mutation (29). priA300 acts as a priA-null mutation when it is combined with a priB-null mutation but has no effect when combined with a priC-null mutation, which was an indication that PriA helicase activity is required for the PriA–PriC pathway. These results suggest that the loss of specificity of PriA helicase activity in priA∆WHD-containing strains selectively inactivates the PriA–PriC pathway. Since the PriA–PriC pathway is thought to be important for restarting stalled replication forks that lack a nascent leading strand proximal to the fork junction (30), these results align well with the dysfunctional activity of EcPriA ∆WHD on such substrates in vitro (Fig. 4A).

priA∆WHD-Containing Strains Exacerbate the UV Sensitivity of recG-Null Strains.

Finally, we investigated the impact of priA∆WHD on recG-null E. coli cells. RecG is a DNA repair helicase that catalyzes DNA replication-fork regression on forks with gaps on the leading strand, which brings nascent strand ends to fork junctions and provides PriA with fork-proximal nascent leading-strand ends. In the absence of this activity, PriA is thought to have access to more forks with leading-strand gaps, where PriA helicase activity can unwind parental duplexes, rendering PriA helicase activity harmful to cells (10, 31). As a consequence, inactivation of recG sensitizes E. coli to DNA-damaging UV light and mutations that inactivate PriA helicase function, such as the priA300 mutation, suppress this phenotype (32, 33). Although priA∆WHD resembled priA300 in priB- and priC-null backgrounds above, the increased level of EcPriA ∆WHD parental duplex unwinding on forks that RecG would normally process (Fig. 4A) led us to hypothesize that priA∆WHD would fail to suppress or may even worsen the UV sensitivity of recG-null strains. To test this, we combined the priA∆WHD mutation with a recG::kan mutation and measured cell survival upon exposure to varying levels of UV light. Consistent with the prediction, combining priA∆WHD with recG::kan led to increased UV sensitivity relative to the recG::kan single mutant (Fig. 6). These results indicate that there are severe consequences for PriA helicase dysregulation on DNA forks.

Discussion

We have examined the mechanisms that govern structure-specific PriA interactions with DNA replication forks and investigated their importance to PriA cellular functions. The 2.8-Å structure of a KpPriA/DNA replication-fork complex resolved the surface that binds to the leading-strand arm of a replication fork. Binding unpaired a segment of the nascent and template leading strands, sequestering the frayed nascent leading 3′ end into an evolutionarily conserved pocket on PriA. Cross-linking studies also identified a WHD interaction with parental duplex DNA that was critical for the specificity of PriA helicase activity on DNA forks lacking a nascent leading strand. On replication forks of this type, a PriA variant in which the WHD was removed unwound both lagging-strand and parental duplex DNAs in vitro. In vivo, the priA∆WHD mutation eliminated the PriA–PriC replication restart pathway and was detrimental when combined with a recG mutation, consistent with altered helicase activity on replication-fork structures lacking fork-proximal nascent leading strands. These observations highlight the importance of regulating PriA helicase orientation on DNA replication forks and show that dysregulation of PriA has severe consequences for pathways that act on replication forks with leading-strand gaps.

Although the PriA/replication-fork structure presented here revealed continuous electron density for only the leading-strand arm of a DNA replication fork, additional observations provided constraints that allow assembly of an experimentally supported model of PriA bound to a full DNA replication fork (Fig. 7A). These constraints include WHD/parental duplex cross-links (Fig. 2A) and previously determined PriA/lagging-strand DNA cross-links (20) mapped onto DNA molecules from structural superimpositions with similar domains/proteins. The overall model that arises from these constraints positions the replication-fork junction near the aromatic-rich loop/motif IIa region of the helicase domain, which is consistent with previous cross-linking results (20) and with the location of the parental leading +1 base in the KpPriA/DNA structure. Noncontinuous electron density that could be explained by phosphate (from DNA) or sulfate ions (from crystallization conditions) was also adjacent to the aromatic-rich loop in both the KpPriA/DNA and EcPriA ∆WHD structures reported here (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B). Leading, lagging, and parental arms each project away from the junction and are bound by different PriA domains in the model. The interactions in this model agree remarkably well with previous DNase footprinting studies that showed significant protection of segments from all three arms of a fork structure by PriA, along with a gap in protection on the parental arm (16, 18) (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Helicase lobe 1 may interact with and account for protection of parental duplex near the fork junction, consistent with previous cross-linking from this domain (20), whereas the WHD accounts for the fork-distal parental duplex interaction. PriA interaction with each arm has been proposed to be maintained throughout the DNA replication restart process (10, 19), which agrees with the high affinity that PriA has for DNA fork junctions and with the hand-off mechanism model for DNA replication restart (34). If PriA interfaces with the leading strand and parental duplex are maintained during helicase activity on the lagging strand, unwound parental lagging-strand DNA would be forced to form a loop as it is formed. This loop may be bound by other proteins in the replication restart complexes (PriB, PriC, or DnaT) and, ultimately, the loop could be used as a loading site for the replicative DnaB helicase.

Fig. 7.

Model of the full PriA/DNA replication-fork complex and roles of the 3′BD and WHD in PriA orientation on a DNA fork. (A) PriA/DNA fork model. The model was constructed from the KpPriA/DNA structure (Fig. 1, leading arm), dsDNA from structural superimposition with the WHD of OhrR (22) onto the PriA WHD (parental duplex), and structural superimposition of DNA from the RecQ/DNA complex (50) with the helicase core (lagging arm). The overall assembly was energy-minimized using the SYBYL-X 2.1 molecular modeling system. The PriA/DNA fork model fits PriABpa-DNA fork cross-linking constraints from this or a previous study (latter indicated by asterisk) (20), with dotted lines indicating the site of the mutated EcPriA residue in the KpPriA structure and the nucleotide site(s) of the cross-link (from PE disruption). (B) Scheme of PriA on a DNA fork that would result in the varied helicase products observed in Fig. 4.

The resolved interaction between PriA and leading-arm dsDNA splits the nascent and parental leading strands and sequesters the 3′ end of the nascent strand into a conserved 3′BD pocket (Fig. 1). Leading-strand binding involves surfaces from both the 3′BD and CTD of PriA. This binding arrangement is consistent with the specificity that PriA has for replication forks containing a nascent leading-strand end (Fig. 1) (14, 15). We note that the use of 3′ end sequestration/leading-strand fraying as a replication-fork stabilization mechanism may be conserved in proteins that process stalled DNA replication forks in eukaryotic as well. The PriA 3′BD is structurally homologous to the HIRAN domain of HLTF, which also interacts with 3′ ends of DNA replication forks (35). This interaction is required for the DNA replication-fork reversal activity of HTLF and a PriA-like interaction that frays the leading strand could be critical for this process. While the PriA/leading-strand interaction is not involved in PriA helicase activity on that strand, leading-strand fraying enables 3′ end engagement by PriA, which is a known determinant in orienting the helicase core for unwinding of the lagging arm on replication forks (8). We hypothesize that PriA sequestration of the 3′ end is also critical for preventing unwarranted use of the 3′ end by polymerases or other enzymes until after DNA replication restart is complete and PriA has dissociated, as has been observed previously (11–13).

The structural and biochemical experiments described here have also shown the PriA WHD to be a mobile domain that plays an important role in structure-specific helicase activity on replication forks lacking a nascent leading strand. The KpPriA/DNA structure identified two WHD positions, each of which differs from the position observed in the published apo KpPriA structure (9). All three locations were stabilized by crystal packing, which suggests that the position of the WHD is dynamic in solution. Although DNA was not observed bound to the WHD in the KpPriA/DNA structure, WHDBpa-DNA cross-linking mapped an interaction between the domain and parental DNA ∼11–24 bp upstream of the fork junction (Fig. 2C). This distance exceeded the parental DNA length used in the crystals and crystallization trials with longer parental DNA failed, preventing direct visualization of the WHD/DNA interface. In the model of PriA bound to a full replication fork, the WHD was fixed using cross-linking constraints to the parental duplex DNA and the parental duplex was joined with the remainder of the replication-fork model (Fig. 7A). A WHD/DNA fork interaction at this position requires significant unraveling of the linker segments that connect the WHD to the remainder of PriA. This conformational rearrangement could be a signal for binding to bona fide replication-fork structures rather than DNA structures, such as ssDNA or dsDNA, that are more commonly found in the bacterial chromosome.

Examination of the helicase activities of a PriA variant that lacked the WHD further supported an important role for the domain in proper recognition of replication-fork structures. We found that removal of the WHD from PriA led to unwinding of both lagging-strand and parental duplexes in replication forks that lacked a nascent leading strand (Figs. 4 and 7B). SSB is known to bias full-length PriA activity toward the lagging strand and EcPriA ∆WHD did exhibit an increased amount of lagging-strand products in the presence of SSB; however, SSB was not sufficient to properly orient EcPriA ∆WHD. In contrast, the presence of a nascent leading strand was sufficient to orient EcPriA ∆WHD (Fig. 4C). Although the WHD likely contributes to the PriA/DNA fork interaction (SI Appendix, Figs. S4 and S5A), EcPriA ∆WHD retained high affinity for forked DNA (Fig. 3) and we suggest that the WHD is important as a specificity domain rather than as a major protein/DNA stabilizing interface. Indeed, the isolated WHD had only modest affinity for DNA (Fig. 3) (16). Despite its low intrinsic DNA-binding affinity, the PriA WHD interacts with dsDNA in the context of the PriA/DNA fork complex (Fig. 2) and, in doing so, helps to orient the helicase domain for lagging-strand DNA unwinding (Fig. 7B). Thus, removal of the WHD leads to dysregulated unwinding of parental duplex DNA by PriA (Figs. 4 and 7B). Crystallographic and cross-linking attempts to probe this orientation of PriA ∆WHD on replication-fork structures failed to produce diffracting crystals or significant PE bands. This may be due to the heterogeneous nature of the PriA ∆WHD/replication-fork structure in which the helicase domain can be bound in different locations (parental or lagging strands) in different complexes. Related to these findings, previous studies using the PriA helicase core domain found SSB failed to properly target helicase activity to the lagging strand, resulting in dyregluated parental duplex unwinding (36). In the case of WT PriA, the presense of SSB likely helps restrict PriA binding to the fork junction (9, 37), which could help the PriA WHD to interact with dsDNA parental duplex. When combined with the PriA/leading-strand interface, this interaction would leave the helicase core to act on the lagging-strand arm of the replication fork.

The altered specificity of the PriA ∆WHD variant provided an experimental tool for probing the importance of PriA structure-specific activity in E. coli. Consistent with this specificity being critical for PriA function on replication forks with leading-strand gaps in vivo, deleting the WHD from priA inactivated the PriA–PriC restart pathway (observed in ∆priB background) and increased the UV-light sensitivity of recG-null cells (Figs. 5 and 6). The common link between the PriA–PriC pathway and RecG is that each relies on similarly structured DNA substrates–DNA replication forks lacking a fork-proximal nascent leading strand (30, 38). On this fork type, EcPriA ∆WHD carried out a dysfunctional activity in which it unwound parental DNA (Fig. 4A). To carry out this reaction the helicase domain of EcPriA ∆WHD must incorrectly load onto the leading arm rather than the lagging arm and then translocate in the direction of the parental DNA (Fig. 7B). Thus, it appears that the PriA WHD helps to prevent such problematic loss of specificity and facilitates proper functioning of the PriA–PriC pathway. The PriA–PriC pathway requires PriA helicase activity (29, 39, 40), and, on PriC-preferred replication forks in the presence of SSB, EcPriA ∆WHD unwound less substrate than WT PriA, forming less of the lagging-strand-unwound DNA fork (Fig. 4A). RecG also prevents harmful PriA helicase activity by competing for binding to forks with leading-strand gaps and remodeling these forks until the 3′ end is at the fork junction. In doing so, RecG provides PriA with substrates that strongly orient PriA away from parental duplex unwinding (10, 31). To this end, PriA helicase activity becomes harmful to cells in the absence of RecG, and removal of PriA helicase activity can complement the UV sensitivity of recG-null strains (32). Dysregulated DNA unwinding in the priA∆WHD strain exacerbated the UV sensitivity of recG-null strains compared with that of wild-type priA (Fig. 6). Considering the role of RecG in preventing PriA parental duplex unwinding, results with the novel priA variant are consistent with an increase in parental duplex unwinding by PriA ∆WHD as observed in vitro. In conclusion, this work has revealed important mechanisms that govern structure-specific activities in PriA and has led to insights into mechanisms of cellular genome maintenance.

Materials and Methods

Protein Purification.

pET-15b–derived plasmids encoding N-terminal His-tagged EcPriA ∆WHD [EcPriA with residues 115–174 removed through introduction of an Eco RV site that inserted an Asp-Ile linker at the site of deletion between Pro114 and Asp175 (ANAP-DI-DLAS)] and the isolated WHD (expressing residues 114–174 from EcPriA) were created and the proteins expressed in Rosetta2 E. coli. N-terminal His-tagged KpPriA was expressed using pET28-KpPriA-transformed Rosetta2 E. coli. Bpa EcPriA variants were expressed from a pBAD/His B vector in BL21 E. coli cotransformed with pSup-MjTyrRS-6tRNA (41). All PriA variants were purified as described previously for EcPriA (20), with some exceptions for the isolated WHD. The isolated WHD was thrombin-cleaved and reapplied to a Ni column during purification to remove the His tag and a S100 size-exclusion chromatography column was used instead of an S300 column. SSB was purified as described previously (42).

Crystallization and Structure Determination.

KpPriA was prepared for crystallization by buffer exchange at room temperature into minimal buffer A [20 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM ammonium acetate, 5 mM magnesium acetate, 120 μM ADP, and 5 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine)] and concentrated to 67.5 μM. The DNA fork was prepared by combining oTW208, oTW250, and oTW251 (SI Appendix, Table S1) at a 1:1:1 molar ratio in 10 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mM ammonium acetate, and 6.35 mM magnesium acetate, heating to 95 °C, incubating at 70 °C for 1 h, and cooling to room temperature over 3 h. KpPriA was crystallized with the DNA fork at 1:1.2 protein:DNA fork molar ratio, respectively, by mixing 0.8 μL well solution (85 mM sodium citrate-NaOH, pH 5.6, 250 mM ammonium sulfate, 750 mM lithium sulfate, and 4% glycerol), with 0.2 μL 325 μM annealed DNA fork, 0.2 μL additive (50 mM spermidine tetrahydrochloride, 0.2 M praseodymium acetate, 1–2 mM ADP, or water), and 0.8 μL of KpPriA (67.5 μM) in hanging-drop vapor diffusion experiments at 20 °C. Initial crystals formed after 3 d, with a second round of crystals appearing after 12–16 d. Crystal formation was dependent on the presence of DNA and was dependent on the length and end identity (overhangs) of the parental duplex and leading ds ends of the DNA. Crystals were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen after cryoprotecting the crystals in well solution supplemented with increased salt (1.8 M lithium sulfate and 1.04 M ammonium sulfate final). X-ray diffraction data were collected at 11 keV at the Advanced Photon Source beamline 21-ID-D. Data were processed using XDS (43). Datasets from three different 2.9- to 3.1-Å-resolution crystals were scaled together using XSCALE (44). The structure of the KpPriA/DNA complex was determined by molecular replacement using the apo KpPriA structure [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 4NL4; ref. 9] with the WHD separated as a search model in the program Phenix.Phaser (45). A final model was obtained after rounds of model building using Coot (46) and refining with Phenix.refine (45). Coordinate and structure factor files have been deposited in the PDB (ID code 6DGD).

EcPriA ∆WHD was dialyzed at 4 °C in minimal buffer B (10 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0, and 200 mM ammonium sulfate), concentrated to 10 mg/mL, and Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine) was added to 1 mM. EcPriA ∆WHD was mixed with well solution (50 mM Hepes-HCl, pH 7.5, 9.5% PEG 4000, 4% isopropanol, 8% glycerol, and 50 mM sodium malonate) 1:1 (vol:vol) and incubated for 40 min at room temperature before centrifuging at high speed for 10 min; 1.8 μL EcPriA ∆WHD/well solution mix was combined with 0.2 μL of 0.25–1 M sodium fluoride before hanging-drop vapor diffusion crystallization at 20 °C. Crystals formed within 1 d. After 2 d, crystals were cryoprotected in well solution supplemented with 91 mM ammonium sulfate, 4.55 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0, and 30% glycerol and flash-frozen. X-ray diffraction data were collected at 11.0 keV at the Advanced Photon Source beamline 21-ID-D. Data were processed using XDS (43). The EcPriA ∆WHD structure was determined by molecular replacement using the apo KpPriA structure (PDB ID code 4NL4; ref. 9) with the WHD removed as a search model in Phenix.autosolve (45). A final model was obtained after rounds of model building using Coot (46) and refining with Phenix.refine (45). Coordinate and structure factor files have been deposited in the PDB (ID code 6DCR).

DNA Fraying Assay.

The 2-AP DNA fraying was analyzed using the same fork as that used in the fluorescence anisotropy and helicase assays (discussed below), except that 2-AP replaced the 3′-terminal nucleotide of the synthetic nascent leading strand and the parental strand sequence was correspondingly changed for base pairing. B-33, 3L-98, oTW240, and oTW239 (SI Appendix, Table S1) were annealed at 10 μM (1:1:1:1 molar ratio) in 10 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM sodium chloride, and 1 mM EDTA by heating at 95 °C for 5 min and cooling 1°/min to 25 °C. Varying concentrations of PriA were incubated with 300 nM annealed fork in 25 mM Hepes-HCl, pH 8.0, 4 mM magnesium acetate, 5% glycerol, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mg/mL BSA, and 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol for 30 min at room temperature. The fluorescence intensity of the samples was measured for 30 s with excitation at 315 nm and emission at 370 nm using a QuantaMaster 400 spectrofluorometer (Photon Technology International). This concentration of labeled DNA yielded a strong excitation peak at 315 nM and emission peak at 370 nM. The contribution from tryptophan was minimal at these settings but protein-alone samples were measured with each titration and the protein-alone fluorescence intensity was subtracted from each point. Nonlabeled fork (negative control) and an unquenched fork (positive control with four noncomplementary bases on the parental strand across from the 2-AP) were measured alongside each replicate. Data are presented as the mean ± SD for three independently measured titrations.

Fluorescence Anisotropy DNA-Binding Assays.

Fluorescence anisotropy DNA-binding assays were performed as described previously (20), except that forked DNA was prepared and analyzed alongside a dsDNA and ssDNA substrates (SI Appendix, Table S1). Fluorescence intensity increased [∼1.8-fold for forked DNA, 1.6- to 1.7-fold for dsDNA, and 1.4- (EcPriA) or 1.2- (EcPriA ∆WHD) fold for ssDNA] over increasing concentrations of EcPriA and EcPriA ∆WHD and fluorescence anisotropy was corrected for this change as described previously (20). The isolated WHD did not yield a change in fluorescence intensity over titration with this protein.

For off-rate measurements, samples were processed as above, except that PriA variant (25 nM final) was incubated with labeled fork (1 nM final) for 30 min at room temperature in 90 μL of the final 100 μL. Samples were measured at this point before the addition of vast excess of unlabeled DNA fork competitor (250 nM final; 10 μL) and fluorescence was measured every minute for 4 h. Data were fit to a two-phase decay exponential equation (GraphPad Prism), and k1 (fast rate), k2 (slow rate), and the percent at k1 were averaged from five replicates (mean ± SD is reported). Equilibrium PriA/DNA binding under these conditions (before competitor addition) was confirmed. Various concentrations of competitor unlabeled DNA fork were analyzed to confirm that the off rates were not dependent on the concentration of competitor. Additionally, we confirmed 250 nM unlabeled DNA was sufficient to prevent any reassociation with labeled fork by adding labeled fork after incubation with the competitor. Rates were compared for measurements beyond 4 h, and time course measurements were confirmed to begin 10-fold below t1/2 and 10-fold beyond t1/2. Off rates without competitor were run alongside as a control and to test for photobleaching. We also tested nonspecific competitors (heparin, ssDNA, and yeast RNA) but found that none of these competitors (at any concentration tested) could inhibit association of PriA with labeled fork DNA.

Helicase Assays.

Helicase assays were performed as described previously (20).

PriABpa-DNA UV Cross-Linking.

UV cross-linking was performed as described previously (20).

EMSAs.

EMSAs were preformed as described previously (20).

PriA/DNA Cross-Link PE Assay.

PE was performed as described previously (20). PE was performed ± ADP to confirm that the inclusion of ADP did not alter conclusions.

Strains and Media.

All bacterial strains were derivatives of E. coli K-12 and are described in SI Appendix, Table S3. The protocol for P1 transduction has been described previously (47). All P1 transductions were selected on 2% agar plates made with either LB or 56/2 minimal media (supplemented with 0.2% glucose, 0.001% thiamine, and specified amino acids and containing the appropriate antibiotics) (47). Kanamycin (kan) was used at 50 μg/mL, chloramphenicol (cam) at 25 μg/mL, ampicillin at 50 μg/mL and tetracycline at 10 μg/mL. All transductants were grown at 37 °C and purified on the same type of media on which they were selected.

Construction of priA∆WHD on Chromosome.

An M7 derivative with the dnaC809,820 mutation was used. The strain was made priA2::kan by P1 transduction. The resulting strain was transformed with pMAX4 and grown on LB-cam at 30 °C. This was made by cloning the priA∆WHD[(del(priA)333] allele in the BamHI-SalI restrictions sites of pKO3. This fragment was produced by PCR using prSJS1361 and prSJS1362 on pUC-PriA∆WHD [WHD deletion matches that used for protein purification (above)]. Recombination between the plasmid and chromosomal copies of priA was stimulated by incubating the strain at 37 °C on LB-cam. A second round of recombination was stimulated by incubating the strain at 30 °C on LB without antibiotic. Strains were then screened for kan sensitivity and the priA∆WHD mutation was confirmed by PCR.

Preparation and Analysis of Cells for Microscopy.

The cells for SOS expression were prepared, imaged, and analyzed as previously described (48). Briefly, cells were grown in minimal media to midlog phase and 1 mL of the cells were centrifuged and resuspended in ∼100 μL; 2 μL of that suspension was added to a 1% agarose slab. A coverslip was then applied on top of the cells. Images (phase contrast and fluorescence) were taken for at least nine different fields of view (three on three different days) for each strain. These images were analyzed by a combination of OpenLabs v5.5, MicrobeTracker, and MATLAB R2014a programs (Improvision, Inc.; ref. 49 and MathWorks, Inc.) The relative fluorescence intensity was calculated by dividing the mean of pixel value of a cell by the normal pixel value of a wild-type cell (JC13509) not containing ∆attλ::sulApΩgfp-mut2 (26). The average relative intensity was the average intensity for the entire population of cells. Programs written in MATLAB R2014a were used to analyze the binary and fluorescent images to produce the data in Fig. 5C. Statistical analysis of the data was performed using Student’s t test.

UV-Sensitivity Assay.

Cells were grown in minimal media until they reached midlog phase. Cultures were irradiated with UV light (254 nm) at an intensity of 1 J/m2 for the appropriate amount of time. Serial dilutions were performed on the cultures and 5 μL droplets were put on minimal media plates. The plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C in the dark. Survival was established by comparing the viable unit count before and after exposure to UV light. Statistical analysis of the data was performed using Student’s t test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Life Sciences Collaborative Access Team at the Advanced Photon Source (Argonne National Laboratory), Basudeb Bhattacharyya, Craig Bingman, Anastasiia Klimova, Steven Van Alstine, and Caroline Qin, for their assistance and advice and Shawn Laursen for assisting in protein purification; Jason Chin and Peter Schultz for plasmids; and Nick George for SSB protein. We thank the J.L.K. laboratory, S.J.S. laboratory, and Matthew Lopper for critical evaluation of the manuscript. This work was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant DGE-1256259 (to T.A.W.) and National Institutes of Health Grant GM098885 (to J.L.K. and S.J.S.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: Coordinate and structure factor files for the KpPriA/DNA and EcPriA deltaWHD structures have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.wwpdb.org (PDB ID codes 6DGD and 6DCR, respectively).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1809842115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Cox MM, et al. The importance of repairing stalled replication forks. Nature. 2000;404:37–41. doi: 10.1038/35003501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mangiameli SM, Merrikh CN, Wiggins PA, Merrikh H. Transcription leads to pervasive replisome instability in bacteria. eLife. 2017;6:e19848. doi: 10.7554/eLife.19848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Windgassen TA, Wessel SR, Bhattacharyya B, Keck JL. Mechanisms of bacterial DNA replication restart. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:504–519. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jezewska MJ, Bujalowski W. Interactions of Escherichia coli replicative helicase PriA protein with single-stranded DNA. Biochemistry. 2000;39:10454–10467. doi: 10.1021/bi001113y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szymanski MR, Jezewska MJ, Bujalowski W. The Escherichia coli PriA helicase-double-stranded DNA complex: Location of the strong DNA-binding subsite on the helicase domain of the protein and the affinity control by the two nucleotide-binding sites of the enzyme. J Mol Biol. 2010;402:344–362. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arai K, Kornberg A. Unique primed start of phage phi X174 DNA replication and mobility of the primosome in a direction opposite chain synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:69–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.1.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zipursky SL, Marians KJ. Escherichia coli factor Y sites of plasmid pBR322 can function as origins of DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:6111–6115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.10.6111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones JM, Nakai H. Escherichia coli PriA helicase: Fork binding orients the helicase to unwind the lagging strand side of arrested replication forks. J Mol Biol. 2001;312:935–947. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhattacharyya B, et al. Structural mechanisms of PriA-mediated DNA replication restart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:1373–1378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318001111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanaka T, Masai H. Stabilization of a stalled replication fork by concerted actions of two helicases. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:3484–3493. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510979200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu L, Marians KJ. PriA mediates DNA replication pathway choice at recombination intermediates. Mol Cell. 2003;11:817–826. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuan Q, McHenry CS. Strand displacement by DNA polymerase III occurs through a tau-psi-chi link to single-stranded DNA-binding protein coating the lagging strand template. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:31672–31679. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.050740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manhart CM, McHenry CS. The PriA replication restart protein blocks replicase access prior to helicase assembly and directs template specificity through its ATPase activity. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:3989–3999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.435966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sasaki K, et al. Structural basis of the 3′-end recognition of a leading strand in stalled replication forks by PriA. EMBO J. 2007;26:2584–2593. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mizukoshi T, Tanaka T, Arai K, Kohda D, Masai H. A critical role of the 3′ terminus of nascent DNA chains in recognition of stalled replication forks. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:42234–42239. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300285200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanaka T, Mizukoshi T, Sasaki K, Kohda D, Masai H. Escherichia coli PriA protein, two modes of DNA binding and activation of ATP hydrolysis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:19917–19927. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701848200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zavitz KH, Marians KJ. Helicase-deficient cysteine to glycine substitution mutants of Escherichia coli replication protein PriA retain single-stranded DNA-dependent ATPase activity. Zn2+ stimulation of mutant PriA helicase and primosome assembly activities. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:4337–4346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu J, Marians KJ. PriA-directed assembly of a primosome on D loop DNA. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25033–25041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.35.25033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manhart CM, McHenry CS. Identification of subunit binding positions on a model fork and displacements that occur during sequential assembly of the Escherichia coli primosome. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:10828–10839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.642066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Windgassen TA, Keck JL. An aromatic-rich loop couples DNA binding and ATP hydrolysis in the PriA DNA helicase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:9745–9757. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galardy RE, Craig LC, Printz MP. Benzophenone triplet: A new photochemical probe of biological ligand-receptor interactions. Nat New Biol. 1973;242:127–128. doi: 10.1038/newbio242127a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hong M, Fuangthong M, Helmann JD, Brennan RG. Structure of an OhrR-ohrA operator complex reveals the DNA binding mechanism of the MarR family. Mol Cell. 2005;20:131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clark KL, Halay ED, Lai E, Burley SK. Co-crystal structure of the HNF-3/fork head DNA-recognition motif resembles histone H5. Nature. 1993;364:412–420. doi: 10.1038/364412a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winkelman JT, et al. Crosslink mapping at amino acid-base resolution reveals the path of scrunched DNA in initial transcribing complexes. Mol Cell. 2015;59:768–780. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCool JD, Sandler SJ. Effects of mutations involving cell division, recombination, and chromosome dimer resolution on a priA2:kan mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8203–8210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121007698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCool JD, et al. Measurement of SOS expression in individual Escherichia coli K-12 cells using fluorescence microscopy. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53:1343–1357. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marceau AH, et al. Structure of the SSB-DNA polymerase III interface and its role in DNA replication. EMBO J. 2011;30:4236–4247. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bi EF, Lutkenhaus J. FtsZ ring structure associated with division in Escherichia coli. Nature. 1991;354:161–164. doi: 10.1038/354161a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sandler SJ, McCool JD, Do TT, Johansen RU. PriA mutations that affect PriA-PriC function during replication restart. Mol Microbiol. 2001;41:697–704. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heller RC, Marians KJ. The disposition of nascent strands at stalled replication forks dictates the pathway of replisome loading during restart. Mol Cell. 2005;17:733–743. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Azeroglu B, et al. RecG directs DNA synthesis during double-strand break repair. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1005799. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al-Deib AA, Mahdi AA, Lloyd RG. Modulation of recombination and DNA repair by the RecG and PriA helicases of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6782–6789. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6782-6789.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaktaji RP, Lloyd RG. PriA supports two distinct pathways for replication restart in UV-irradiated Escherichia coli cells. Mol Microbiol. 2003;47:1091–1100. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lopper M, Boonsombat R, Sandler SJ, Keck JL. A hand-off mechanism for primosome assembly in replication restart. Mol Cell. 2007;26:781–793. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kile AC, et al. HLTF’s ancient HIRAN domain binds 3′ DNA ends to drive replication fork reversal. Mol Cell. 2015;58:1090–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen HW, North SH, Nakai H. Properties of the PriA helicase domain and its role in binding PriA to specific DNA structures. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38503–38512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404769200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Szymanski MR, Jezewska MJ, Bujalowski W. The Escherichia coli PriA helicase specifically recognizes gapped DNA substrates: Effect of the two nucleotide-binding sites of the enzyme on the recognition process. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:9683–9696. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.094789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGlynn P, Lloyd RG. Rescue of stalled replication forks by RecG: Simultaneous translocation on the leading and lagging strand templates supports an active DNA unwinding model of fork reversal and Holliday junction formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8227–8234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111008698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boonsombat R, Yeh S-P, Milne A, Sandler SJ. A novel dnaC mutation that suppresses priB rep mutant phenotypes in Escherichia coli K-12. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:973–983. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sandler SJ. Multiple genetic pathways for restarting DNA replication forks in Escherichia coli K-12. Genetics. 2000;155:487–497. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.2.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ryu Y, Schultz PG. Efficient incorporation of unnatural amino acids into proteins in Escherichia coli. Nat Methods. 2006;3:263–265. doi: 10.1038/nmeth864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.George NP, et al. Structure and cellular dynamics of Deinococcus radiodurans single-stranded DNA (ssDNA)-binding protein (SSB)-DNA complexes. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:22123–22132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.367573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kabsch W. Xds. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kabsch W. Integration, scaling, space-group assignment and post-refinement. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:133–144. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Willetts NS, Clark AJ, Low B. Genetic location of certain mutations conferring recombination deficiency in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1969;97:244–249. doi: 10.1128/jb.97.1.244-249.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Massoni SC, Sandler SJ. Specificity in suppression of SOS expression by recA4162 and uvrD303. DNA Repair (Amst) 2013;12:1072–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sliusarenko O, Heinritz J, Emonet T, Jacobs-Wagner C. High-throughput, subpixel precision analysis of bacterial morphogenesis and intracellular spatio-temporal dynamics. Mol Microbiol. 2011;80:612–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07579.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Manthei KA, Hill MC, Burke JE, Butcher SE, Keck JL. Structural mechanisms of DNA binding and unwinding in bacterial RecQ helicases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:4292–4297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416746112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.