Abstract

Lifestyle medicine (LM) is recognized as an essential component of evidence-based medical treatment, particularly for chronic diseases. Multiple studies have shown that intensive therapeutic lifestyle change can arrest and reverse disease, including heart disease, type 2 diabetes, essential hypertension, metabolic syndrome, and autoimmune and inflammatory conditions. While more modest lifestyle changes can slow the onset or prevent disease, studies reveal that intensive therapeutic changes are required to arrest and reverse disease. As increasing numbers of clinicians have learned about the powerful treatment effects of intensive lifestyle interventions, interest in LM has greatly increased. This, in turn, has led to the need for evidence-based clinical LM training in how to effectively provide intensive LM interventions that can arrest and reverse disease. As with all clinical training, such training must include actual patient care guided by knowledgeable expert LM clinicians. The purpose of this article is to (1) describe the need for and function of clinical LM specialists, (2) describe the key components in the training of clinical LM specialists to treat and reverse chronic disease, and (3) describe the steps/components in establishing and implementing a clinical LM specialty-training program.

Keywords: lifestyle medicine training, intensive lifestyle interventions, lifestyle medicine curriculum design, clinical lifestyle medicine education

‘The idea that lifestyle changes are only useful for preventing disease has been shown to be incorrect.’

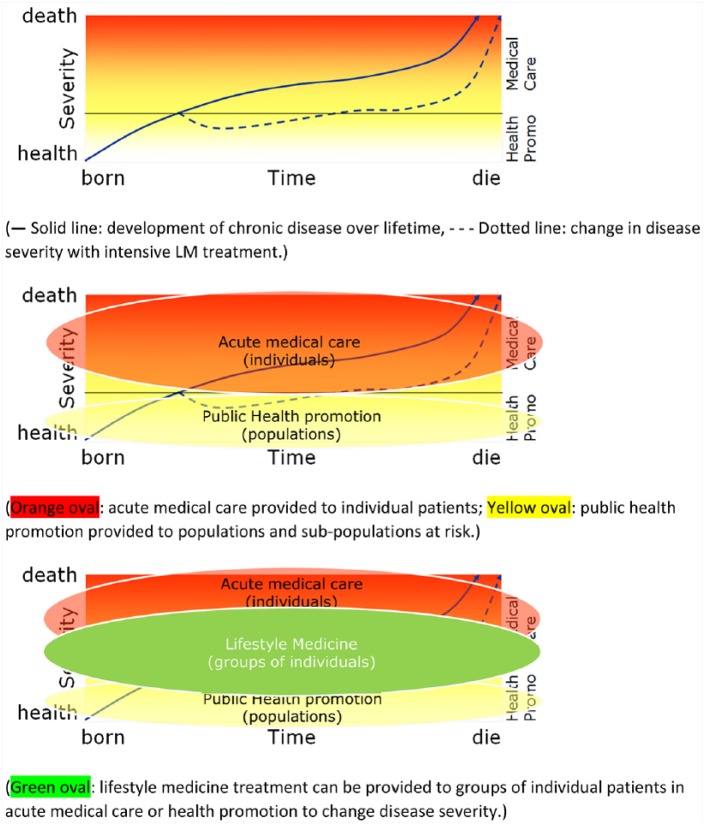

Lifestyle medicine (LM) treatment has grown from its initial conception as primary prevention in patients at risk for developing chronic disease via improved diet, exercise, and stress management, to now being an essential medical treatment for chronic disease and a growing number of acute conditions (Figure 1). The idea that lifestyle changes are only useful for preventing disease has been shown to be incorrect.1,2 Modern medical science recognizes lifestyle interventions as the first line of treatment for a growing number of diseases.3,4 However, how to most effectively provide these interventions is less clear. The optimal “dosing” is not the same for every patient. As with practically every medical treatment, optimal dosing depends on the patient and the nature and severity of his or her disease.

Figure 1.

Lifestyle medicine and acute care versus public health/preventive medicine.

LM was originally shown to be effective in studies where lifestyle intervention dosing was maximized.1,5,6 Patients in the experimental groups received intensive therapeutic interventions delivered over a number of weeks. Treatment utilized a multidisciplinary team and involved multiple extended encounters each week.

Dosing was maximized to ensure that statistically significant treatment effects were seen with a small sample size. In order to demonstrate effectiveness, most studies chose subjects with severe disease that had few treatment options. Due to the severity of their condition, participants were allowed and willing to try something that, until this point, had been experimental.

Once LM interventions were proven to be effective in severe cases with maximized dosing, less severe cases were treated with reduced dosing. Consistent with the normal progression of investigation for a new treatment modality, the dosing route was tested, as well as dosing frequency, and so on, in order to establish a dose-response relationship. One of the renowned interventions with significant research behind it is the Complete Health Improvement Program (CHIP). This program uses trained facilitators to teach live demonstrations that utilize prerecorded presentations given by experts.

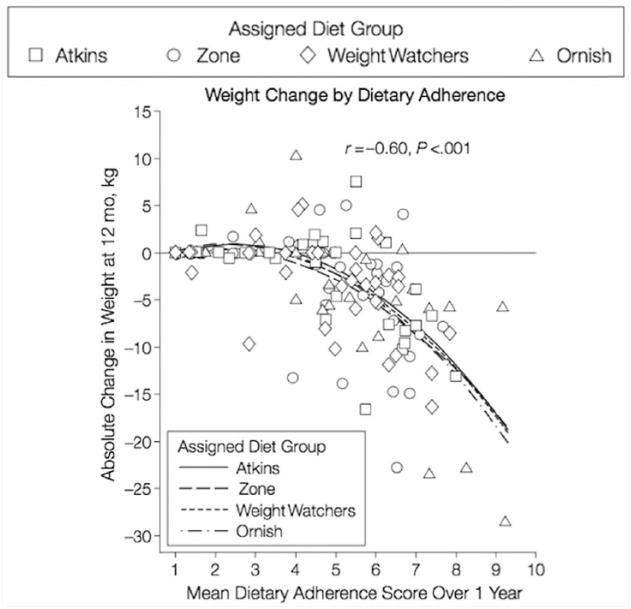

Consistent with other treatments, the best evidence indicates there is indeed a threshold effect for lifestyle change; LM interventions must be sufficiently intense to exceed this threshold and to induce dramatic lifestyle changes7,8 (Figure 2). This is called the “induction phase” as it induces treatment effects. The evidence also indicates that LM treatment has an adherence-dependent half-life such that change must be sustained in order to maintain the treatment effect.9 There is evidence that patients find it easier to maintain adherence when they perceive “the changes are working.”10 A patient’s primary initial motivation is fear—they are afraid of the effects of their disease. Nevertheless, when they see the powerful effects dramatic lifestyle changes have, their sustaining motivation becomes joy—they like how they feel and how the changes reverse their disease.3

Figure 2.

Threshold effect for lifestyle intervention dosing (Dansinger et al7).

(Notice the nonlinear relationship between adherence on the x-axis and change on the y-axis. Changes only begin to occur with adherence above ~4-5).

A minimum level of LM intervention dosing must be maintained in order for the majority of patients to continue to experience therapeutic effects. After the induction phase, patients have seen improvement in how they feel and in their diseases; maintenance is more easily sustained. It is imperative to note that more intensive dosing is required for induction than for sustaining treatment effects.4

Solution

The need for an induction phase, which produces maximum-dose lifestyle success, can best be met by trained, qualified LM specialists. These LM specialists will not only use LM to prevent disease or halt future complications, but they will also be capable of prescribing and providing interventions strong enough to actually reverse chronic disease. The treatments required to produce this level of effect are quite different from those required to sustain changes. This is the “space” in which LM specialists practice—adequate dosing of intensive LM treatment to reverse disease (Figure 2).

A more expansive knowledge of LM is required of the practitioner for maximum intervention dosing. However, there is also a need for the provider to be familiar with a different treatment setting—what can be referred to as the “dosing route.” While brief one-on-one encounters with an LM practitioner can be adequate for low-dose primary prevention interventions or for ongoing support after an intensive induction phase, the intensive induction phase dosing requires multiple, frequent, group encounters ranging 1 to 4 hours in order to maximize treatment effects.3

LM Fellowship Specialty Training

The Lifestyle Medicine Core Curriculum (LMCC) is an excellent resource for acquiring a foundational knowledge of the principles of LM. However, a deeper knowledge of the primary literature is required of those who wish to prescribe higher LM therapies. It is important for those who seek to incorporate sound LM concepts into their medical practices to familiarize themselves with the core competencies,11 but true LM specialists must go beyond these core competencies to develop a broader knowledge and expertise in the field of LM. Specialists must know the literature and the key studies so that they can speak with personal certainty rather than reciting what others have said about the studies and the literature.

LM specialty training must include actual patient care utilizing intensive lifestyle interventions to reverse disease. Lifestyle changes have so long been seen as having mild and very gradual effects that their remarkable results of disease reversal, usually within days or weeks, appears miraculous. Analogous to rotating through intensive care units in hospitals during residency to learn about end-stage disease and to see human physiology first hand, LM specialists need to have immersive experiences to understand and appreciate the power of intensive LM treatment.

LM specialists need more exposure than a standard brief office visit approach. Published research shows that brief one-on-one office visits are usually inadequate to produce the dramatic lifestyle changes necessary to maximize doing and reverse disease.12,13 Extended office visit time alone is also inadequate. Intensive, frequent encounters as part of a group are required for disease reversal and the training of an LM specialist.

Fellowship Curriculum

Training of clinical LM specialists should include the following key components:

Completing an intensive LM treatment program as a mock patient. This introduces the fellow to LM from the patient’s perspective, and helps the fellow improve his or her own lifestyle.

Performing medical visits in a working LM center with residential or nonresidential patients while under the close supervision of an LM specialist. Increasing independence should be given as the fellow increases in LM competency. The fellow should be able to oversee at least one intensive intervention program without the preceptor’s direct involvement, using him or her only as a consultant.

Participating in LM literature reviews to become familiar with the primary LM literature. This should include written and oral presentations to the preceptor.

Developing clinical workflows and protocols to optimally integrate LM into primary care, or if applicable, corporate sponsored employee wellness programs. This helps fellows consolidate their knowledge into concrete clinical treatment plans.

Completing the American College of Lifestyle Medicine (ACLM)/American College of Preventive Medicine (ACPM) LMCC course and receiving a certificate of completion. The core competencies are foundational to the practice of LM.

Developing and maintaining a personal wellness-promoting lifestyle while serving as a fellow. This helps fellows “walk it” and not simply “talk it.”

Collaborate on LM outcomes research using actual patient data, including coauthoring a publishable article on LM. This helps fellows understand the difference between clinical medicine and research. It also helps them appreciate the need for rigorous data collection and analysis.

When applicable, regularly interact with corporate sponsors to track and monitor progress of training.

Each of these components are important in developing the knowledge base and clinical expertise necessary to function as an expert (specialist) and be capable of teaching other practitioners. It is generally accepted that specialists should possess the knowledge and skills to produce better (more ideal, quicker, defter) results than nonspecialists. LM specialty training must do that for practitioners who choose to specialize in the use of therapeutic lifestyle interventions to treat and reverse disease.

Developing a Fellowship

The following steps or parts are needed to develop a fellowship training program:

Establish or find a working LM specialty practice that uses intensive lifestyle interventions that reverse disease.

Develop sufficient capacity and staffing to properly engage and train fellows. This includes a preceptor with the knowledge, skill, and passion for teaching. These characteristics are necessary to inspire, explain, guide, and model LM.

Develop a thorough curriculum including most of the components described above. This curriculum should utilize clinical relationships with local medical groups interested in LM, such as cardiology and endocrinology, where the fellow may be able to give talks and answer questions among traditional medical providers. Preceptors should also develop an exercise that challenges the fellows to compare and contrast what they would have done previously with a select patient versus the treatment they would have used before learning about LM to what they did after learning how to use LM treatments. This exercise can solidify the fellow’s transformation from advocate to specialist more powerfully than any other.

Provide or create a formal fellowship evaluation with valid and specific criteria.

Secure funding for the fellow’s position. Experience indicates that each fellow consumes as much resource as does a residential LM patient. It typically takes months before fellows can generate sufficient additional income for the clinic to offset their cost. This means that fellows must either pay handsomely for their training or sponsors must be found.

Market and recruit fellows. However, one should not take just any candidate—be selective, especially in the beginning. These fellows become the public face of your program. Choose them well and give them everything one can. Equip them so that they will excel in whatever aspect of LM they pursue.

An Interview With LM Fellow, Dr Jeni Shull.

Introduction: Jeni Shull, MD, MPH, was the first fellow in the Black Hills Lifestyle Medicine Fellowship. Dr Shull completed her medical degree at Indiana University School of Medicine. She went to Loma Linda University for residencies in family and preventive medicine where she served as chief resident for both programs and was on multiple committees advocating for LM for both patients and colleagues. Upon finishing she joined Dr John Kelly at Black Hills Lifestyle Medicine Center (BHLMC). She started on October 13, 2015, and completed on February 28, 2016. The Cummins Inc sponsored her training. Upon completion of her training, Dr Shull joined Premise Health, the firm that runs the LiveWell Center for Cummins Inc in Columbus, Indiana.

Though my training at Loma Linda was excellent, during my fellowship at BHLMC, I realized I was still severely underestimating the power of lifestyle medicine. I had seen the results of living a healthy life in my centenarian patients, but I had still only read about LM reversing disease. This seemed to be happening under the care of some of the pioneers of the field like Drs Dean Ornish and Caldwell Esselstyn Jr, but far from what I had been able to produce in residency writing dietary and exercise prescriptions. As I began working with Dr Kelly, like an intern writing her first insulin drip orders under the watchful eye of the intensivist, what I had only read about before began working in real life. Several things became very apparent.

Disease reversal is possible—even if you are an average Jane like me, it can happen quickly, and is surprisingly easy (our intensive therapy included a plant diet, 15 minutes/day of resistance training, and a 45-minute walk). A threshold dose of LM is needed. In my previous efforts I had never been able to adequately dose this intervention appropriately.

By not discussing LM treatments with patients as the first line and most optimal therapy, I now feel like it would be malpractice because of the superior outcomes and lower risk profile of LM treatments.

Every patient benefited from LM treatments, even if not every disease was reversed.

Conclusion

LM is a new and developing area of medical practice. It is widely recognized as an essential component in the treatment of chronic disease, but it is not yet part of medical education or clinical medicine. It remains largely unreimbursed, especially the intensive treatment phase. A vacuum exists in the knowledge base and the clinical experience of intensive LM therapy because so few clinicians are practicing intensive LM. Nevertheless, this is changing and the BHLMC is part of this transformation process. More physicians are undergoing and sharing the personal experience Dr Jeni Shull had. Once one has experienced the power and joy of using LM they will never practice medicine the same again.

Final Comments

Visit BHLMC.org or the ACLM training page to learn more about BHLMC training. Come as a professional observer or Professional in Training any time. Consider referring patients to the BHLMC to help them change their lives and perspectives on LM. Adequate dosing of the most powerful medical treatment available can make all the difference in providing true health care. LM is the most marvelous form of medical practice! It transforms lives. It gives people their lives back. It empowers people to do things they had given up on achieving. It may be just the medicine that the doctor has been looking for!

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: This article is based on a keynote presentation delivered at the American College of Lifestyle Medicine 2016 Annual Meeting, October 25, 2016

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Ornish DM, Brown SE, Scherwitz LW, et al. Can lifestyle changes reverse coronary atherosclerosis? The Lifestyle Heart Trial. Lancet. 1990;336:129-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jenkins DJ, Kendall CW, Marchie A, et al. Effects of a dietary portfolio of cholesterol-lowering foods vs lovastatin on serum lipids and C-reactive protein. JAMA. 2003;290:502-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.JNC 8 Hypertension guideline algorithm. http://www.nmhs.net/documents/27JNC8HTNGuidelinesBookBooklet.pdf. Accessed February 17, 2016.

- 5. Esselstyn CB., Jr. In cholesterol lowering, moderation kills. Cleve Clin J Med. 2000;67:560-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Franklin BA, Durstine JL, Roberts CK, Barnard RJ. Impact of diet and exercise on lipid management in the modern era. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;28:405-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dansinger ML, Gleason JA, Griffith JL, Selker HP, Schaefer EJ. Comparison of the Atkins, Ornish, Weigh Watchers, and Zone diets for weight loss and heart disease risk reduction: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2005;293:43-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gardner CD, Kiazand A, Alhassan S, et al. Comparison of the Atkins, Zone, Ornish, and LEARN diets for change in weight and related risk factors among overweight premenopausal women: the A TO Z Weight Loss Study: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2007;297:969-977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ornish D. The Spectrum. New York, NY: Ballantine Books; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barnard ND, Cohen J, Jenkins DJ, et al. A low-fat vegan diet improves glycemic control and cardiovascular risk factors in a randomized clinical trial in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1777-1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lianov L, Johnson M. Physician competencies for prescribing lifestyle medicine. JAMA. 2010;304:202-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Davis AM, Sawyer DR, Vinci LM. The potential of group visits in diabetes care. Clin Diabetes. 2008;26(2):58-62. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Weinger K. Group medical appointments in diabetes care: is there a future? Diabetes Spectrum. 2003;16:104-107. [Google Scholar]