Abstract

Intranasal vaccination using dry powder vaccine formulation represents an attractive, non-invasive vaccination modality with better storage stability and added protection at the mucosal surfaces. Herein we report that it is feasible to induce specific mucosal and systemic antibody responses by intranasal immunization with a dry powder vaccine adjuvanted with an insoluble aluminum salt. The dry powder vaccine was prepared by thin-film freeze-drying of a model antigen, ovalbumin, adsorbed on aluminum (oxy)hydroxide as an adjuvant. Special emphasis was placed on the characterization of the dry powder vaccine formulation that can be realistically used in humans by a nasal dry powder delivery device. The vaccine powder was found to have passable to good flow properties, and the vaccine was uniformly distributed in the dry powder. An in vitro nasal deposition study using nasal casts of adult humans showed that around 90% of the powder was deposited in the nasal cavity. Intranasal immunization of rats with the dry powder vaccine elicited a specific serum antibody response as well as specific IgA responses in the nose and lung secretions of the rats. This study demonstrates, for the first time, the generation of systemic and mucosal immune responses by intranasal immunization using a dry powder vaccine adjuvanted with an aluminum salt.

Keywords: Intranasal, vaccine, aluminum salts, dry powder, mucosal immunity, powder characterization

1. Introduction

Adjuvants are needed for newer generation vaccines, such as protein subunit vaccines, to elicit strong immune responses (1). Some insoluble aluminum salts, e.g. aluminum (oxy)hydroxide and aluminum (hydroxy)phosphate, are used in many currently licensed vaccines as adjuvants and possess excellent safety profiles (2, 3). A major limitation of aluminum salt-adjuvanted vaccines is that they must be maintained in cold-chain (2-8 °C) during transport and storage (4). Accidentally subjecting the vaccines to slow freezing compromises their potency and/or efficacy. To overcome this issue, previously we reported that thin-film freeze-drying (TFFD) can be used to convert aluminum salt-adjuvanted vaccine from a liquid dispersion to a dry powder without causing particle aggregation or decreasing immunogenicity following reconstitution (5, 6). Importantly, the resultant dry powder vaccine is not sensitive to slow freezing and can be stored in temperatures as high as 40 °C for up to 3 months (6).

Aluminum salt-adjuvanted vaccines are generally administered by intramuscular, subcutaneous, or intradermal injection. However, reconstituting a dry powder vaccine before injection has various limitations such as the need for sterile water for injection, the need for trained medical personnel, and the increased chance of errors made when reconstituting the powder and filling syringes (7). The nasal route for immunization offers some interesting opportunities. Almost all infectious agents enter the body through the mucosal surfaces (8), and the nasal mucosa is often the first point of contact for inhaled pathogens. Therefore, ideally, to more effectively protect against inhaled pathogens, vaccines should be administered via the nasal mucosal surface to induce mucosal immunity to prevent infectious agents from entering the host (9). Besides enabling vaccines to induce both mucosal and systemic immune responses (10, 11), intranasal immunization has several other advantages as well. For example, the nasal mucosal surface is easily accessible and nasal immunization enables needle-free, non-invasive delivery of vaccines with the possibility of self-immunization.

Previously, it was thought that aluminum salt-based vaccine adjuvants are not capable of potentiating mucosal immune responses when given intranasally, and results from prior studies were ambiguous (12–15). However, data from our recent studies clearly showed that intranasal immunization with an antigen adsorbed on Alhydrogel® induces significantly stronger antigen-specific immune responses, both systemically and in nasal and lung mucosal secretions, as compared to intranasal immunization with the antigen alone (16). In the present study, we tested the feasibility of administering aluminum salt-adjuvanted dry powder vaccine prepared using our thin-film freeze-drying method directly via the nasal route to induce specific mucosal and systemic immune responses in a rat model. Others have administered dry powder vaccines intranasally in animal models (17, 18), and even in clinical trials (19, 20), however these vaccines do not contain aluminum salts as adjuvants (21). Aluminum salt-adjuvanted dry powder vaccine preparations have also been administered in animal model(s) by a needle-free method, but by needle-free intradermal injection (22, 23).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Preparation of dry powder vaccine

The ovalbumin (OVA)-Alhydrogel® dry powder vaccine was prepared as described previously (5, 6). Briefly, OVA-Alhydrogel® liquid vaccine was prepared by adding 10 mL of Alhydrogel® (~10 mg/mL aluminum, manufactured by Brenntag, and supplied by InvivoGen, San Diego, CA) into a 50-mL tube followed by the addition of 10 mL of an OVA solution (1 mg/mL in 0.9% saline solution, w/v), and 200 mg of trehalose (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to obtain a final formulation with 2% (w/v) of trehalose, ~1 % (w/v) of Alhydrogel®, and 0.5 mg/mL of OVA. The vaccine suspension was converted into a dry powder using our previously reported thin-film freeze-drying method (5, 6). The powder was dried using a VirTis Advantage Bench Top Lyophilizer (The VirTis Company, Inc. Gardiner, NY). Lyophilization was performed over 72 h at pressures less than 200 mTorr, while the shelf temperature was gradually ramped up from −40 °C to 26 °C. After lyophilization, the solid dry powder vaccine was transferred into a sealed container and stored in a desiccator at room temperature.

2.2. Physicochemical characterization

2.2.1. Particle size analysis

The geometric diameter of the dry powder vaccine was determined by low angle light scattering using a Malvern Spraytec® (Malvern, UK) outfitted with an inhalation cell and without an induction port. The nasal dry powder delivery device engineered in our laboratory (see Results and discussion section for details) was filled with the powder and then secured to the mouth of the induction port by a molded silicone adapter. The measurement was done at a flow rate of 25 L/min. Data acquisition took place over 4 s and only when laser transmission dropped below 95%.

2.2.2. Powder morphology and uniformity of distribution

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) attached to energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) was applied to understand the structure and morphology of the vaccine dry powder and to determine the uniformity of the distribution of the dry powder vaccine. A Hitachi S-5500 SEM (Hitachi High Technologies America, Inc., Pleasanton, CA) equipped with EDS was used at 10 kV accelerating voltage after sputter-coating the specimen with silver for 30 s in vacuum. Images at different magnifications were photographed from the SEM, and EDS plots showing elemental mapping were reported.

2.2.3. Flow properties

The tapped density of the dry powder vaccine was measured according to a method adapted from the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) <616> method I using a Varian Tapped Density Tester (Varian, Palo Alto, CA) (24). An adaptation was made due to the limited supply of powder for testing, where a 100-mL graduated cylinder was replaced by a 5-mL graduated cylinder. Hausner ratio and Carr’s compressibility index were calculated based on USP guidelines. Measurements of the static angle of repose of the dry powder vaccine were conducted as per USP <1174> (25). Approximately 10 mL of powder was measured using a funnel and a flat collection surface.

2.3. Aerodynamic assessment of the dry powder vaccine

Aerodynamic assessment of the dry powder vaccine intended for nasal administration was performed in a nasal cast model (26). The construction of the nasal casts from computed tomography (CT) scans has been detailed previously (26). Five separate nasal casts were each made from a CT scan of a different adult individual (26). The nasal casts can be divided into four sections representing the anterior region making up the vestibule (V) and nasal valve area; lower, middle and upper turbinates collectively called posterior nasal cavity (P); nasopharynx region (N); and the post-nasal fraction (F), which can either be collected in a cup if the model is operated without simulated inspiration airflow, or a removable filter is connected to the nasopharynx section if operated at a normal nasal breathing of 15 L/min. The cast was coated with 1% (v/v) Tween 20 in methanol and allowed to dry prior to deposition studies to minimize bias caused by particle bounce, similar to impaction studies performed on dry powder inhalers using cascade impactors (27, 28). The dry powder formulation was administered to the cast with a nasal dry powder delivery device prepared in our own laboratory (29) (See Results and discussion section for details). The spray administration angle was set at 60° from horizontal, and the tip of the device was inserted at a distance of 5 mm. After administration, the cast was disassembled, and all parts were washed with 2% nitric acid carefully to collect the deposited fractions. Aluminum content was determined using a Varian 710-ES Inductively Coupled Plasma-Optical Emission Spectrometer (ICP-OES) in the Civil Architectural and Environmental Engineering Department at The University of Texas at Austin. The deposition profile is shown as % deposition recovered in different sections of the cast model and the post-nasal filter.

2.4. Animal study

The animal study was conducted following the U.S. National Research Council Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The University of Texas at Austin approved the animal protocol. Female Sprague-Dowley rats, 6-8 weeks of age, were from Charles River Laboratories Inc. (Wilmington, MA). Rats were dosed intranasally on days 0, 14 and 28 with the OVA-Alhydrogel® dry powder vaccine (IN Powder, n = 4) using the nasal dry powder delivery device engineered in our own lab. Rats were anesthetized and placed on their back at an angle of 45°. The exit diffuser of the device loaded with the vaccine powder was placed in the nostril of the anesthetized rat. The plunger of the syringe that contains 1 mL of air was depressed to create a powder plume of the vaccine in the nasal cavity. As controls, rats were also intranasally dosed with the OVA-Alhydrogel® liquid vaccine (IN Liquid, n = 4), saline (n = 5), or subcutaneously (s.c.) injected with the OVA-Alhydrogel® liquid vaccine (SC Liquid, n = 4). For intranasal dosing of the liquid vaccine and normal saline, rats were placed on their back at an angle of 45° after anesthesia. The liquid vaccine or normal saline was administered using a fine pipette tip into the external nares with 10 μL volume in each nostril. The dose of OVA was 20 μg per rat, and 400 μg for Alhydrogel®, in the IN Liquid and SC Liquid groups. In the IN Powder group, the dose of the OVA in the first immunization was 21.6 ± 3.0 μg per rat. However, in the second and third immunizations, largely because the amount of dry powder vaccine that came out of the nasal dry powder delivery device varied each time, some rats were dosed twice, leading to an increase in the dose of OVA to more than 20 μg per rat (i.e. 49.4 ± 6.6 and 85.7 ± 19.5 μg per rat, respectively). Four weeks after the third dose, rats were euthanized to collect blood, nasal wash, and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). Nasal wash and BAL were collected as previously described by washing with 500 μL of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (30).

The anti-OVA IgG and IgA levels in serum samples, nasal washes, and BAL samples were determined using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (31). Briefly, EIA/RIA flat bottom, NUNC Maxisorp, 96-well plates (Thermo Fisher) were coated with 1 ng/μL of OVA solution in carbonate buffer (0.1 M, pH 9.0) overnight at 4 °C. Plates were blocked with horse serum for one hour before adding the serum samples. Horse radish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled goat anti-rat immunoglobulin (IgG from Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL; IgA from Life Technologies Corporation, Carlsbad, CA; 5000-fold dilution) was added into the plates, and the presence of bound antibody was detected in the presence of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine solution (TMB, Sigma–Aldrich). The absorbance was read at 450 nm.

Rat brain tissues were collected upon euthanasia. The tissues were weighed, desiccated at 60 °C for 12 h, and then incinerated with nitric acid (6.6 N) at 60 °C for 15 h. Aluminum content was determined using an Agilent 7500ce quadruple Inductively Coupled Plasma attached with Mass Spectrometer (ICP-MS) in the Department of Geological Sciences at The University of Texas at Austin. ICP-MS has a detection limit of 1 ng/L (parts per trillion) for aluminum (32). The aluminum levels are normalized to the dry weight of the brain tissues.

Noses of rats were prepared for histological examination. For this, the noses were separated, immobilized and decalcified. Afterwards the samples were sliced horizontally from the nostrils to the nasopharynx, and the slices were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for evaluation under a microscope.

2.5. Statistics

Statistical analyses were completed by performing two-tailed Student’s t-test for two-group analysis or one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis for multiple group comparisons using the GraphPad Prism 7 software (La Jolla, CA). Ap value of ≤ 0.05 (two-tail) was considered significant.

3. Results and discussion

Although search for new vaccine adjuvants continues, insoluble aluminum salt-based adjuvants remain the preferred choice of adjuvants in vaccine formulations. Aluminum salt-adjuvanted vaccines, however, are particularly sensitive to unintentional slow freezing and/or heat during transport and storage, and have to be maintained in cold-chain (2-8 °C). Unfortunately, breaching of the cold-chain is a common place, and not resource-limited (6). To overcome this drawback, we previously reported that thin-film freeze-drying can be used to convert aluminum salt-adjuvanted vaccines from liquid to dry powder without causing particle aggregation or decreasing the immunogenicity following reconstitution (5). The dry powder vaccine was stable in temperature ranging from 4°C to as high as 40°C for up to 3 months and was not sensitive to repeated freezing (6). However, immunization using a hypodermic needle attached to a syringe filled with liquid vaccine that is reconstituted from the dry powder is not without limitations. Data from our recent study showed that it is feasible to administer a liquid dispersion of antigens adsorbed on an aluminum salt (i.e. Alhydrogel®) intranasally to induce specific systemic and mucosal immune responses (16), prompting us to hypothesize that administering an aluminum-salt adjuvanted dry powder vaccine directly to the nose cavity will induce specific systemic and mucosal immune responses. We tested this hypothesis in a rat model with the dry powder of a vaccine prepared with OVA as a model antigen adsorbed on Alhydrogel®, the international standard preparation of aluminum (oxy)hydroxide gel (33, 34). OVA-Alhydrogel® liquid vaccine was converted into a dry powder using our previously reported thin-film freeze-drying method with 2% of trehalose as a cryoprotectant. The dry powder does not contain any known mucoadhesive agent (21).

3.1. Flow properties of the OVA-Alhydrogel® dry powder vaccine

The flow properties measure the cohesive forces of a powder. In this study, the dry powder vaccine was prepared to explore the feasibility of intranasal administration, not their flow properties per se. However, the flow properties do affect the performance of the final product (35). Also, because nasal delivery requires a fluidization of the powder bed, it is conceivable that the flow properties of the dry powder vaccine could affect the emitted dose from the nasal delivery device and the deposition of the vaccine in the nasal cavity.

The bulk and tapped densities of the dry powder was determined to be 0.040 ± 0.003 and 0.051 ± 0.007 g/mL, respectively (Table 1). The Hausner ratio and Carr’s compressibility index of the dry powder vaccine were calculated to be 1.28 ± 0.07 and 21.80 ± 4.25, respectively, indicating that the flow property of the powder is ‘passable’. The angle of repose of the dry powder was determined to be 25.94 ± 6.30°, which indicates a “good” flow property. The discrepancy in the flow property between the two methods of measurement could be explained by the low-density, porous and brittle particles of the thin-film freeze-dried vaccine powder, making a more compact cake when measuring the tapped density (36).

Table 1.

Physical characterization of the thin-film freeze-dried vaccine powder. Data are mean ± S.D. (n = 3).

| Bulk Density (g/mL) | Tap Density (g/mL) | Carr’s Index (CI) | Hausner Ratio | Static Angle of Repose (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.040 ± 0.003 | 0.051 ± 0.007 | 21.80 ± 4.25 | 1.28 ± 0.07 | 25.94 ± 6.30 |

3.2. Powder morphology and uniformity of distribution

SEM/EDS has an X-ray spectrometer attached to SEM, which allows elemental analysis in addition to SEM. SEM/EDS could be employed to determine the qualitative distribution of the OVA-Alhydrogel® dry powder vaccine by taking advantage of the elemental aluminum in the formulation. This analysis gives an indication of how the OVA-Alhydrogel® vaccine is distributed in the dry powder. Shown in Figure 1A are representative SEM images of the OVA-Alhydrogel® dry powder vaccine. As expected, the OVA-Alhydrogel® particles have a rough surface and irregular shape. Three random areas in an SEM graph of the vaccine dry powder (Figure 1A and the left panel of Figure 1B) were chosen for analysis, and four elements, Al, O, Na and Cl, were analyzed. SEM/EDS showed the presence of all four elements analyzed (Figure 1B-C). The spectrum analysis and EDS map indicate a homogeneous distribution of the elements, implying that the vaccine was uniformly distributed in the dry powder.

Figure 1.

SEM/EDS of OVA-Alhydrogel® dry powder vaccine. Shown in (A) are representative SEM images of the dry powder vaccine at different magnifications. (B) A randomly selected area in a SEM graph (left panel), and representative elemental mapping (right panel, bars = 6 μm). (C) EDS spectra of the elements tested (Al, O, Na, Cl; n = 3 random areas).

3.3. Intranasal dry powder delivery device and characterization of dry powder delivered using the device

A nasal dry powder delivery device was developed in our lab for this study (29). The device includes a housing reservoir (e.g. the square-shaped base of an oral gavage needle) and a pressurizing mechanism operable to pressurize gas/air chamber (e.g. similar to a syringe) to desired pressure (29). The dry powder vaccine was loaded into the housing reservoir. Depressing the syringe plunger pushes air through the device, creating a powder plume that exits the orifice of the device (Figure 2A). The particle size of the OVA-Alhydrogel® dry powder vaccine delivered with the device was measured using a Malvern’s Spraytec instrument and shown in Figure 2B. The median diameter of the powder was 12.55 ± 4.69 μm.

Figure 2.

(A) OVA-Alhydrogel® powder cloud evolving from the nasal dry powder delivery device prepared in house. (B) A representative particle size distribution curve of the OVA-Alhydrogel® dry powder vaccine.

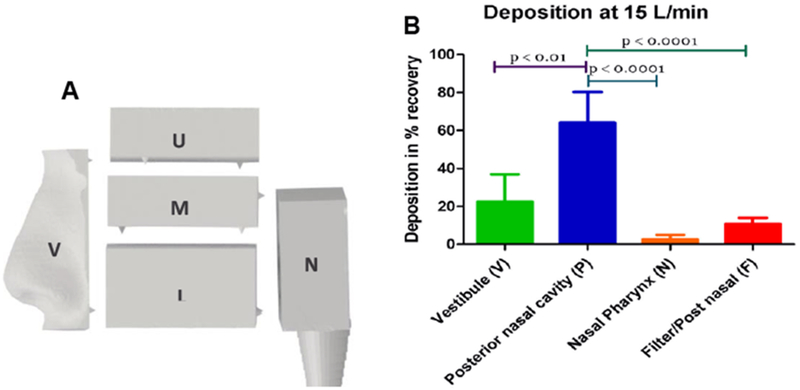

3.4. Aerodynamic assessment of dry powder vaccine

The nasal cavity is the most easily accessible part of the respiratory system. It is worth noting that release of antigen from vaccine powder in the nasal cavity must take into account several factors, including wettability, dissolution rate, and the interaction of antigen-adjuvant with the mucus. However, for a nasal vaccine to afford protection, vaccines must present antigen to the target lymphoid tissues in nose. Nose-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT) in rodents refers to a pair of aggregated lymphoid tissues in the bottom of nasal ducts. However, in human nose cavity, the Waldeyer’s ring, a well-known group of tonsils that includes the adenoid, tubal, palatine, and lingual tonsils, is the key lymphoid tissue (37). A post mortem study by Debertin et al. (2003) provided evidence of the existence of NALT , in addition to the Walderyer’s ring, in young children (38). Pabst stated that there is not any reported data on the frequency of NALT in adolescents and adults (39).

Evaluation of the nasal deposition of the dry powder vaccine would be beneficial in the development of nasal vaccines, because there are no guidelines or international consensus regarding the relationship between aerosol characteristics and deposition sites within the nasal cavities (40). We used nasal casts based on the CT scans of five adult humans to predict the deposition of the dry powder vaccine after nasal administration. Figure 3A shows the representative image of the different sections of the nasal casts used. The deposition study was carried out at 15 L/min of flow rate. As depicted in Figure 3B, 62.20 ± 8.14% the vaccine dry powder was recovered from the casts. Of the recovered powder, 64% was in the posterior nasal cavity. Overall, the nasal deposition can be deemed good, considering that out of the total powder recovered, about 90% stayed in the nose, and only around 10% of the powder was in the post-nasal fraction.

Figure 3.

(A) A diagram of the different sections of the nasal cast used. The vestibule (V) and nasal valve area make up the anterior region; The upper (U), middle (M), and lower (L) turbinate regions are collectively called posterior nasal cavity (P); and N indicates the nasopharynx. (B) Deposition of the OVA-Alhydrogel® dry powder vaccine in nasal casts operated at 15 L/min. F indicates the post-nasal fraction. Data are mean ± S.D. from 5 adult casts.

3.5. The immunogenicity of the dry powder vaccine after intranasal administration

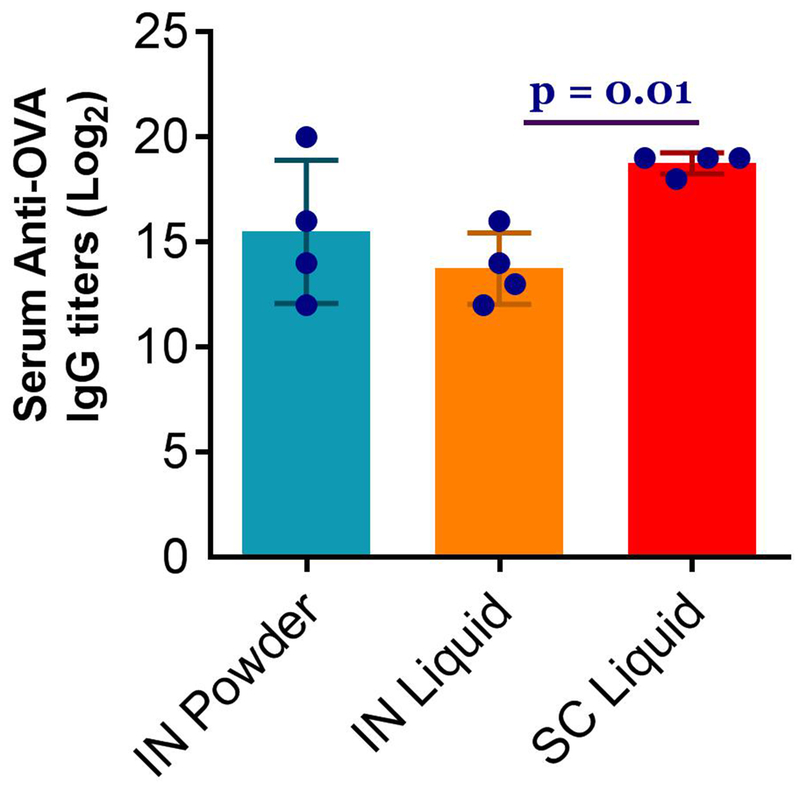

To evaluate the feasibility of administering the OVA-Alhydrogel® dry powder vaccine directly to the nose (IN Powder) to induce immune responses, rats were nasally administered with the dry powder vaccine using our nasal dry powder delivery device. The immune responses induced by the OVA-Alhydrogel® liquid vaccine after intranasal administration (IN Liquid) and subcutaneous injection (SC Liquid) as positive controls were also assessed. Shown in Figure 4 are the OVA-specific antibody responses induced, i.e. serum IgG titers and mucosal IgA titers in nasal wash and BAL. Intranasal administration of the OVA-Alhydrogel® dry powder vaccine induced OVA-specific IgG response in rat serum samples (Figure 4A) as well as OVA-specific IgA in rat nasal wash and BAL samples (Figure 4B-C). H&E staining of rat nasal cavities did not reveal any histological difference in the nasal mucosal tissues among rats that received the OVA-Alhydrogel® dry powder intranasally, the OVA-Alhydrogel® liquid vaccine intranasally or subcutaneously, or normal saline intranasally (data not shown), indicating that the OVA-Alhydrogel® dry powder vaccine was well tolerated locally when given intranasally.

Fig. 4.

Serum anti-OVA IgG titers and mucosal IgA titers in rats immunized with OVA-Alhydrogel® dry powder vaccine intranasally. Rats (n = 4–5) were dosed on days 0, 14 and 28 with the dry powder vaccine intranasally (IN Powder), the liquid vaccine intranasally (IN Liquid), or subcutaneously with the liquid vaccine (SC Liquid). The dose of OVA was 20 μg per rat, and 400 μg for Alhydrogel®, in the IN Liquid and SC Liquid groups. For the IN Powder group, the dose of OVA in the first immunization was 21.6 ± 3.0 μg per rat. However, in the second and third immunizations, some rats were dosed twice, leading to an increase in the dose of OVA to more than 20 μg per rat. The anti-OVA IgG titers in serum samples (A), OVA-specific IgA titers in the nasal washes (B) and BAL samples (C) were measured 28 days after the third immunization. The titers in B and C are means from two different measurements. In (A), p = 0 .001, IN Liquid vs SC Liquid. In (B), n.s., not significant, IN Liquid vs. SC Liquid. In (C), p = 0 .01, IN Liquid vs. SC Liquid.

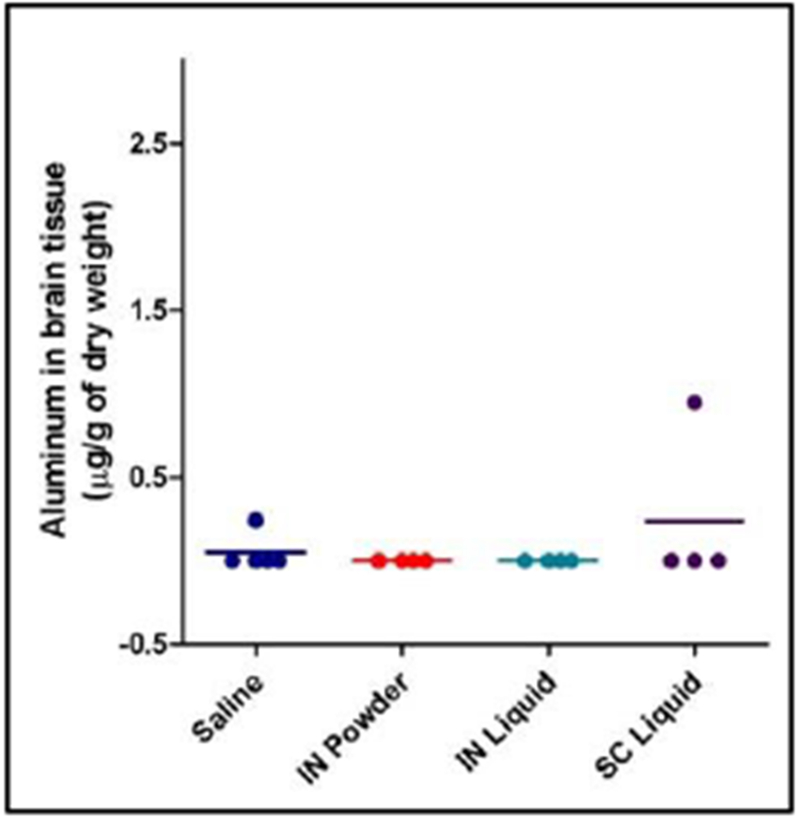

3.6. The level of aluminum in the brain at the end of the study

Aluminum containing adjuvants possess an excellent safety profile (33, 41, 42), and it was suggested that all the injected aluminum salts may be dissolved and absorbed eventually (43, 44). Due to the large size of the particulates in the OVA-Alhydrogel® vaccine dry powder and the OVA-Alhydrogel® liquid vaccine (i.e. X50 of ~12 μm and 8 μm, respectively), the OVA-Alhydrogel® particles are expected to largely stay in the nasal cavity after nasal administration (45, 46). However, there is a potential of brain exposure of aluminum via the olfactory epithelium (47–49). In some previous studies, no significant brain aluminum levels were seen in rats after 4 weeks of continuous exposure of insoluble aluminum (oxy)hydroxide (48), but others showed elevated brain levels of aluminum in rabbits after one month of continuous nasal exposure of soluble aluminum salts in a solution (e.g. aluminum lactate or aluminum chloride, as ‘Gelfoam’) (49). Therefore, we measured aluminum levels in the brain tissues of the immunized rats upon euthanasia (i.e. four weeks after the last immunization). Figure 5 shows the levels of aluminum determined in rat brain tissues. There was not any significant difference in aluminum levels among all four groups, suggesting that intranasal administration of the OVA-Alhydrogel® vaccine dry powder may not increase the level of aluminum in the brain as compared to subcutaneous injection of the OVA-Alhydrogel® liquid vaccine. For rodents, about 50% of the nasal cavity is lined with olfactory epithelium, compared to 3% for humans (50), which will likely further limit nose to brain transport of aluminum in humans, if any. Only a systemic comparison of the aluminum levels in brain tissues at different time points after the vaccine is given intranasally as a dry powder or subcutaneously or intramuscularly as a liquid dispersion at exactly the same dose will allow us to understand whether intranasal administration of the vaccine dry powder will affect its level in the brain. Nonetheless, it is unlikely that the transient nasal exposure of the insoluble aluminum salt in a dry powder vaccine for 1-3 times at a relatively low dose would lead to a significantly elevated level of aluminum in the brain, as compared to when the same dose of insoluble aluminum salt-adjuvanted vaccine is given by the traditional intramuscular injection.

Figure 5.

Aluminum levels in rat brain tissues. Brain was collected 28 days after the third immunization, desiccated, and then incinerated before determining aluminum content in the samples using ICP-MS. Data are mean ± S.D. (n = 4). ANOVA did not reveal any difference among all four groups.

As mentioned earlier, we have shown that our dry powder vaccine can overcome the stability issue of liquid aluminum salt-adjuvanted vaccines (i.e. sensitive to heat and slow freezing) (6). There have been a few reported studies investigating intranasal delivery of dry powder vaccines (17–20, 51–65). However, to our best knowledge, the present study represents the first study testing the feasibility of intranasal immunization with an aluminum salt-adjuvanted dry powder vaccine. Existing human nasal vaccines (e.g., FluMist®, Nasovac®) are live attenuated vaccines (66). Subunit vaccines provide more challenges for nasal immunization, in part due to the low immunogenicity of subunit protein antigens, as compared to live attenuated vaccines (67). Therefore, the availability of proper adjuvant (s) plays a critical role for successful nasal mucosal immunization. For decades, scientists have been searching for a safe and effective nasal mucosal vaccine adjuvant, with only limited success. Our data showed that the aluminum salts in existing injectable human vaccines may be used as nasal mucosal vaccine adjuvants (16). Administering aluminum salt-adjuvanted vaccine powder intranasally can potentially address the cold-chain requirement associated with aluminum salt-adjuvanted liquid vaccines as well as the limitations associated with filling liquid vaccines reconstituted from dry powder into syringes for hypodermic needle-based injection.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, we presented data demonstrating the feasibility of intranasally administering a dry powder vaccine adjuvanted with an aluminum salt to induce specific mucosal and systemic immune responses in a rat model, although the doses of the antigen for the dry powder vaccine were 2.3- and 3.9-fold higher than those for the liquid vaccine in the second and third immunizations, respectively. Further studies using comparable doses are required to fully assess and compare the immunogenicity of the dry powder and liquid vaccines.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AI105789 to ZC), the Alfred and Dorothy Mannino Fellowship in Pharmacy at UT Austin (to ZC), and The University of Texas at Austin Graduate School Dean’s Fellowship (to ST). A.M.A. is a King Abdullah International Medical Research Center (KAIMRC) Scholar and was supported by the KAIMRC Scholarship Program. S.A.V. was supported in part by the Becas-Chile Scholarship from the Government of Chile. R.A. is supported in part by a scholarship from the King Saud University. The authors would like to thank Dr. Hugh Smyth at the UT Austin for kindly allowing us to use the Sympatec Helos laser diffraction instrument available in his lab.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mbow ML, De Gregorio E, Valiante NM, Rappuoli R. New adjuvants for human vaccines. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010. June;22(3):411–6. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Hagan Derek T., MacKichan Mary Lee, Singh M Recent developments in adjuvants for vaccines against infectious diseases. Biomolecular Engineering. 2001;18:69–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh Manmohan, O’Hagan D Advances in vaccine adjuvants. Nature Biotechnology. 1999;17:1075–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milstien JB, Kartoglu Um, Zaffran M, Galazka AM. Temperature sensitivity of vaccines. World Health Organization; 2006;WHO/IVB/06.10. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li X, Thakkar SG, Ruwona TB, Williams RO, Cui Z. A method of lyophilizing vaccines containing aluminum salts into a dry powder without causing particle aggregation or decreasing the immunogenicity following reconstitution. Journal of Controlled Release. 2015;204:38–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thakkar SG, Ruwona TB, Williams RO 3rd, Cui Z The immunogenicity of thin-film freeze-dried, aluminum salt-adjuvanted vaccine when exposed to different temperatures. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017. April 03;13(4):936–46. PubMed PMID: Pubmed Central PMCID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaccines: ensuring sustainable supplies. Médecins Sans Frontières Access Campaign. 2012 November/29/2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mestecky J, Moldoveanu Z, Michalek S, Morrow C, Compans R, Schafer D, et al. Current options for vaccine delivery systems by mucosal routes. Journal of controlled release. 1997;48(2):243–57. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis SS. Nasal vaccines. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001. September 23;51(1-3):21–42. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hashigucci K, Ogawa H, Ishidate T, Yamashita R, Kamiya H, Watanabe K, et al. Antibody responses in volunteers induced by nasal influenza vaccine combined with Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin B subunit containing a trace amount of the holotoxin. Vaccine. 1996. February;14(2):113–9. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith DJ, Bot S, Dellamary L, Bot A. Evaluation of novel aerosol formulations designed for mucosal vaccination against influenza virus. Vaccine. 2003. June 20;21(21–22):2805–12. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butler WT, Rossen RD, Wenden RD. Effect of physical state and route of inoculation of diphtheria toxoid on the formation of nasal secretory and serum antibodies in man. J Immunol. 1970. June;104(6):1396–400. PubMed PMID: . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isaka M, Yasuda Y, Kozuka S, Miura Y, Taniguchi T, Matano K, et al. Systemic and mucosal immune responses of mice to aluminium-adsorbed or aluminium-non-adsorbed tetanus toxoid administered intranasally with recombinant cholera toxin B subunit. Vaccine. 1998. October;16(17):1620–6. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Isaka M, Yasuda Y, Taniguchi T, Kozuka S, Matano K, J M. Comparison of systemic and mucosal responses of mice to aluminium-adsorbed diphtheria toxoid between intranasal administration and subcutaneous injection. Nagoya medical journal. 2001;45(1):5–15. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawson LB, Norton EB, Clements JD. Defending the mucosa: adjuvant and carrier formulations for mucosal immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2011. June;23(3):414–20. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu H, Ruwona TB, Thakkar SG, Chen Y, Zeng M, Cui Z. Nasal aluminum (oxy)hydroxide enables adsorbed antigens to induce specific systemic and mucosal immune responses. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017. November 2;13(11):2688–94. PubMed PMID: Pubmed Central PMCID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang J, Garmise RJ, Crowder TM, Mar K, Hwang CR, Hickey AJ, et al. A novel dry powder influenza vaccine and intranasal delivery technology: induction of systemic and mucosal immune responses in rats. Vaccine. 2004. December 21;23(6):794–801. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garmise RJ, Staats HF, Hickey AJ. Novel dry powder preparations of whole inactivated influenza virus for nasal vaccination. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2007. October 12;8(4):E81 PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McNeela EA, Jabbal-Gill I, Illum L, Pizza M, Rappuoli R, Podda A, et al. Intranasal immunization with genetically detoxified diphtheria toxin induces T cell responses in humans: enhancement of Th2 responses and toxin-neutralizing antibodies by formulation with chitosan. Vaccine. 2004. February 25;22(8):909–14. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Kamary SS, Pasetti MF, Mendelman PM, Frey SE, Bernstein DI, Treanor JJ, et al. Adjuvanted intranasal Norwalk virus-like particle vaccine elicits antibodies and antibody-secreting cells that express homing receptors for mucosal and peripheral lymphoid tissues. J Infect Dis. 2010. December 01;202(11):1649–58. PubMed PMID: Pubmed Central PMCID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bahamondez-Canas TF, Cui Z. Intranasal immunization with dry powder vaccines. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2018. January;122:167–75. PubMed PMID: Pubmed Central PMCID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maa YF, Zhao L, Payne LG, Chen D. Stabilization of alum-adjuvanted vaccine dry powder formulations: mechanism and application. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences. 2003. February;92(2):319–32. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen D, Endres RL, Erickson CA, Weis KF, McGregor MW, Kawaoka Y, et al. Epidermal immunization by a needle-free powder delivery technology: immunogenicity of influenza vaccine and protection in mice. Nat Med. 2000. October;6(10):1187–90. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.United States Pharmacopeia <616> bulk density and tapped density USP 29/NF 24 ed. ed: U.S. Pharmacopoeial Convention: Rockville: MD; 2006. p. 2638. [Google Scholar]

- 25.United States Pharmacopeia <1174> Powder Flow USP 29/NF 24 ed. ed: U.S. Pharmacopoeial Convention: Rockville, MD; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warnken ZN, Smyth HD, Davis DA, Weitman S, Kuhn J, Williams III RO. Personalized medicine in nasal delivery: the use of patient-specific administration parameters to improve nasal drug targeting using 3 D printed nasal replica casts Molecular Pharmaceutics 2018;15(4):1392–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scherließ R, Trows S. Novel formulation concept for particulate uptake of vaccines via the nasal associated lymphoid tissue. Procedia in Vaccinology. 2011;4:113–9. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mitchell J Practices of coating collection surfaces of cascade impactors: A survey of members of the European Pharmaceutical Aerosol Group (EPAG). Drug Deliv Lung. 2003;14:75–8. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cui Z, Thakkar SG, Dry adjuvanted immune stimulating compositions and use thereof for mucosal administration patent, U.S. Provisional Patent Application No0. 62/597,037, 2017.

- 30.Lowrie DB, Whalen RG. DNA vaccines: methods and protocols: Springer Science & Business Media; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sloat BR, Sandoval MA, Hau AM, He Y, Cui Z. Strong antibody responses induced by protein antigens conjugated onto the surface of lecithin-based nanoparticles. Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society. 2010. January 4;141(1):93–100. PubMed PMID: Pubmed Central PMCID: Epub 2009/09/05.eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elemental T. AAS, GFAAS, ICP or ICP-MS? Which technique should I use. An elementary overview of elemental analysis. 2001.

- 33.Thakkar SG, Cui Z. Methods to Prepare Aluminum Salt-Adjuvanted Vaccines In: Fox CB, editor. Vaccine Adjuvants: Methods and Protocols. Methods in Molecular Biology: Springer; New York; 2017. p. 181–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stewart-Tull D Recommendations for the assessment of adjuvants (immunopotentiators). Immunological adjuvants and vaccines: Springer; 1989. p. 213–26. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin AN, Swarbrick J, Cammarata A. Physical pharmacy: physical chemical principles in the pharmaceutical sciences. 1993.

- 36.Watts AB, Wang YB, Johnston KP 3rd WRO. Respirable low-density microparticles formed in situ from aerosolized brittle matrices. Pharmaceutical research. 2013. March;30(3):813–25. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hellings P, Jorissen M, Ceuppens JL. The Waldeyer’s ring. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Belg. 2000;54(3):237–41. PubMed PMID: . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Debertin A, Tschernig T, Tönjes H, Kleemann W, Tröger H, Pabst R. Nasal-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT): frequency and localization in young children. Clinical & Experimental Immunology. 2003;134(3):503–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pabst R Mucosal vaccination by the intranasal route. Nose-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT)-Structure, function and species differences. Vaccine. 2015. August 26;33(36):4406–13. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Le Guellec S, Le Pennec D, Gatier S, Leclerc L, Cabrera M, Pourchez J, et al. Validation of anatomical models to study aerosol deposition in human nasal cavities. Pharmaceutical research. 2014. January;31(1):228–37. PubMed PMID: Pubmed Central PMCID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gupta RK, Relyveld EH, Lindblad EB, Bizzini B, Ben-Efraim S, Gupta CK. Adjuvants—a balance between toxicity and adjuvanticity. Vaccine. 1993;11(3):293–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Hagan DT. Vaccine Adjuvants: Preparation methods and Research protocols. Gupta RK, Rost BE, editors: Humana Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Flarend RE, Hem SL, White JL, Elmore D, Suckow MA, Rudy AC, et al. In vivo absorption of aluminium-containing vaccine adjuvants using 26Al. Vaccine. 1997. Aug-Sep;15(12–13):1314–8. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hem SL. Elimination of aluminum adjuvants. Vaccine. 2002. May 31;20 Suppl 3:S40–3. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hatch TF. Distribution and deposition of inhaled particles in respiratory tract. Bacteriol Rev. 1961. September;25:237–40. PubMed PMID: Pubmed Central PMCID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stuart BO. Deposition of inhaled aerosols. Arch Intern Med. 1973. January;131(1):60–73. PubMed PMID: . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Djupesland PG, Mahmoud RA, Messina JC. Accessing the brain: the nose may know the way. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013. May;33(5):793–4. PubMed PMID: Pubmed Central PMCID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pauluhn J Pulmonary toxicity and fate of agglomerated 10 and 40 nm aluminum oxyhydroxides following 4-week inhalation exposure of rats: toxic effects are determined by agglomerated, not primary particle size. Toxicol Sci. 2009. May;109(1):152–67. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Perl DP, Good PF. Uptake of aluminium into central nervous system along nasal-olfactory pathways. Lancet. 1987. May 02;1(8540):1028 PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harkema JR, Carey SA, Wagner JG. The Nose Revisited: A Brief Review of the Comparative Structure, Function, and Toxicologic Pathology of the Nasal Epithelium. Toxicologic Pathology. 2006 2006/April/01;34(3):252–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dehghan S, Tafaghodi M, Bolourieh T, Mazaheri V, Torabi A, Abnous K, et al. Rabbit nasal immunization against influenza by dry-powder form of chitosan nanospheres encapsulated with influenza whole virus and adjuvants. Int J Pharm. 2014. November 20;475(1–2):1–8. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jiang G, Joshi SB, Peek LJ, Brandau DT, Huang J, Ferriter MS, et al. Anthrax vaccine powder formulations for nasal mucosal delivery. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences. 2006. January;95(1):80–96. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang SH, Kirwan SM, Abraham SN, Staats HF, Hickey AJ. Stable dry powder formulation for nasal delivery of anthrax vaccine. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences. 2012. January;101(1):31–47. PubMed PMID: Pubmed Central PMCID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Springer MJ, Ni Y, Finger-Baker I, Ball JP, Hahn J, DiMarco AV, et al. Preclinical dose-ranging studies of a novel dry powder norovirus vaccine formulation. Vaccine. 2016. March 14;34(12):1452–8. PubMed PMID: Pubmed Central PMCID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ball JP, Springer MJ, Ni Y, Finger-Baker I, Martinez J, Hahn J, et al. Intranasal delivery of a bivalent norovirus vaccine formulated in an in situ gelling dry powder. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0177310 PubMed PMID: Pubmed Central PMCID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang J, Mikszta JA, Ferriter MS, Jiang G, Harvey NG, Dyas B, et al. Intranasal administration of dry powder anthrax vaccine provides protection against lethal aerosol spore challenge. Hum Vaccin. 2007. May-Jun;3(3):90–3. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Klas SD, Petrie CR, Warwood SJ, Williams MS, Olds CL, Stenz JP, et al. A single immunization with a dry powder anthrax vaccine protects rabbits against lethal aerosol challenge. Vaccine. 2008. October 9;26(43):5494–502. PubMed PMID: Pubmed Central PMCID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tafaghodi M, Rastegar S. Preparation and in vivo study of dry powder microspheres for nasal immunization. J Drug Target. 2010. April;18(3):235–42. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mills KH, Cosgrove C, McNeela EA, Sexton A, Giemza R, Jabbal-Gill I, et al. Protective levels of diphtheria-neutralizing antibody induced in healthy volunteers by unilateral priming-boosting intranasal immunization associated with restricted ipsilateral mucosal secretory immunoglobulin a. Infect Immun. 2003. February;71(2):726–32. PubMed PMID: Pubmed Central PMCID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Coucke D, Schotsaert M, Libert C, Pringels E, Vervaet C, Foreman P, et al. Spray-dried powders of starch and crosslinked poly(acrylic acid) as carriers for nasal delivery of inactivated influenza vaccine. Vaccine. 2009. February 18;27(8):1279–86. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Huo Z, Sinha R, McNeela EA, Borrow R, Giemza R, Cosgrove C, et al. Induction of protective serum meningococcal bactericidal and diphtheria-neutralizing antibodies and mucosal immunoglobulin A in volunteers by nasal insufflations of the Neisseria meningitides serogroup C polysaccharide-CRM197 conjugate vaccine mixed with chitosan. Infect Immun. 2005. December;73(12):8256–65. PubMed PMID: Pubmed Central PMCID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mikszta JA, Sullivan VJ, Dean C, Waterston AM, Alarcon JB, Dekker JP 3rd, et al. Protective immunization against inhalational anthrax: a comparison of minimally invasive delivery platforms. J Infect Dis. 2005. January 15;191(2):278–88. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wimer-Mackin S, Hinchcliffe M, Petrie CR, Warwood SJ, Tino WT, Williams MS, et al. An intranasal vaccine targeting both the Bacillus anthracis toxin and bacterium provides protection against aerosol spore challenge in rabbits. Vaccine. 2006. May 1;24(18):3953–63. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Velasquez LS, Shira S, Berta AN, Kilbourne J, Medi BM, Tizard I, et al. Intranasal delivery of Norwalk virus-like particles formulated in an in situ gelling, dry powder vaccine. Vaccine. 2011;29(32):5221–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ramirez K, Wahid R, Richardson C, Bargatze RF, El-Kamary SS, Sztein MB, et al. Intranasal vaccination with an adjuvanted Norwalk virus-like particle vaccine elicits antigen-specific B memory responses in human adult volunteers. Clin Immunol. 2012. August;144(2):98–108. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lycke N Recent progress in mucosal vaccine development: potential and limitations. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012. July 25;12(8):592–605. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wilson-Welder JH, Torres MP, Kipper MJ, Mallapragada SK, Wannemuehler MJ, Narasimhan B. Vaccine adjuvants: current challenges and future approaches. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences. 2009. April;98(4):1278–316. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]