Abstract

Background:

Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is the premalignant lesion of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) and is the target of early detection and prevention efforts for EAC.

Aims:

We sought to evaluate what proportion and temporal trends of EAC patients had missed opportunities for screening and surveillance of BE.

Methods:

Our study included 182 patients with EAC at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston, Texas between 02/2005 and 09/2017. We conducted a retrospective audit of patients’ medical records for any previous upper endoscopies (EGD’s) for screening or surveillance of BE prior to their EAC diagnosis.

Results:

The mean age of the cohort was 67.3 years (SD=9.5); 99.5% of patients were male and 85.2% were white. Only 45 patients (24.7%) had EGD at any time prior to the cancer diagnosing EGD, of whom 29 (15.9% of all EAC cases) had an established BE diagnosis. In the 137 patients with no prior EGD, most (63.5%) had GERD or were obese or ever smokers. There were no changes in patterns over time. For the 29 patients with prior established BE, 22 (75.8%) were diagnosed with EAC as a result of surveillance EGD. Patients with prior established BE were more likely to be diagnosed at 0 or I stage (p<0.001) and managed with endoscopic or surgical modalities (p<0.001) than patients without prior BE.

Conclusions:

Despite having established risk factors for BE, the majority of EAC patients had no prior EGD to screen for BE. BE screening may represent the largest missed opportunity to reduce EAC mortality.

Keywords: Esophageal adenocarcinoma, Barrett’s esophagus, Screening and surveillance, Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), quality improvement, GERD, guidelines

INTRODUCTION

The incidence and mortality of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) has been increasing in Western countries over the past four decades [1]. The overall 5-year survival rate for EAC patients is 17%; with median survival less than 12 months [2, 3]. Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is the only known precursor lesion of EAC and is the target of primary prevention and early detection efforts for EAC.

Current practice guidelines recommend screening for BE among patients with multiple risk factors associated with EAC such as age 50 years or older, male sex, white race, chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms, and obesity [4–6]. Once the diagnosis of BE is established, periodic endoscopic surveillance is recommended in order to detect dysplasia and early cancer [5, 7]. Endoscopic surveillance of BE has been shown to be associated with better EAC outcomes, including lower risk of cancer-related mortality [8].

Despite guidelines to screen for BE and to perform surveillance endoscopies for those with established BE, the effect of these efforts on EAC risk and diagnosis are unclear. In a semi closed healthcare system like the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), one can expect a change in the mode of EAC diagnosis with increasing screening and surveillance activities. We therefore conducted a retrospective audit of patients newly diagnosed with EAC and determined (1) how many had any previous upper endoscopies (EGDs) for screening or surveillance of BE prior to their EAC diagnosis, and (2) whether or not these patterns had changed over time. Furthermore, we sought to evaluate what proportion of EAC patients had missed opportunities for screening and surveillance of BE.

METHODS

Study population

This study included all patients diagnosed with EAC between 02/2005 and 09/2017 at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston, Texas. We retrieved all cases of esophageal cancer from the institution’s cancer registry, and then selected only EAC patients for a structured manual review of their entire VA electronic medical records though the Computerized Patient Record System. We searched all providers’ procedural as well as non- procedural notes. For the non-procedural notes (e.g., consult notes, progress notes), we ran an electronic word search for following words: “EGD, upper endoscopy, GERD, Barrett’s”. We also looked for VA care elsewhere, which is available through the VA portal. For non-VA care, we searched the scanned records from outside the VA for any endoscopy. We collected information on demographics (age at EAC diagnosis, gender and race/ethnicity), date of first clinical encounter with the VA medical system, and established risk factors for BE and EAC (GERD diagnosis, body mass index [BMI], and smoking status). From endoscopy and pathology reports for the period from the patient’s first VA encounter to their EAC diagnosis date, we collected information on the presence of BE (yes, no) and dysplasia status (none, indefinite, low-grade or high-grade). We also used these reports to determine the indication for each endoscopy (i.e., screening, surveillance, or other). Date of EAC diagnosis, cancer stage at diagnosis and treatment were ascertained from the cancer registry data file. Patients with “established BE” had confirmed histological diagnosis of BE for at least 6 months prior to their EAC diagnosis. We defined “proper BE surveillance” if a patient underwent appropriate surveillance EGD for BE based on findings from previous endoscopies (e.g. within 3–5 years after diagnosis of BE with no dysplasia). We defined missed opportunities for screening and surveillance of BE as: 1) failure to screen for BE in high risk patients, defined as male patients aged >50 years with GERD and at least one of obese, former or current smokers, or white ethnicity, 2) failure to diagnose BE in those that had a prior endoscopy, and 3) improper BE surveillance and treatment. Among the patients with missed opportunities, we investigated factors that may have contributed to failure to screen, survey, or treat BE. We also conducted a sensitivity analysis using only EAC patients diagnosed during 2013–2017, in whom we examined their history as far back as 2008. Therefore, the entirety of their clinical care follows the 2008 clinical practice guidelines. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center under the premise of a quality improvement project.

Statistical analysis:

We compared characteristics between EAC patients with and without prior BE, and between EAC patients with and without a prior EGD using Chi-square analyses for categorical variables and two-sample Student’s t-tests for continuous variables. To examine for potential changes over time in the proportions of EAC patients with prior established BE, we fit a Poisson model with year as the time effect, number of EAC as the offset (log transformed) and prior established BE status as the response count. We calculated the annual percent change using an unadjusted model, as well as a model adjusted for age and history of GERD. All analyses were performed using Stata 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Statistical significance was determined at α = 0.05, and all P values for statistical significance were 2-sided.

RESULTS

We identified 182 patients with newly diagnosed EAC between 02/2005 and 09/2017. The mean age of the cohort was 67.3 years (SD=9.5 years); 99.5% of these patients were male and 85.2% were white.

Missed opportunity 1 (No screening for BE in high-risk groups)

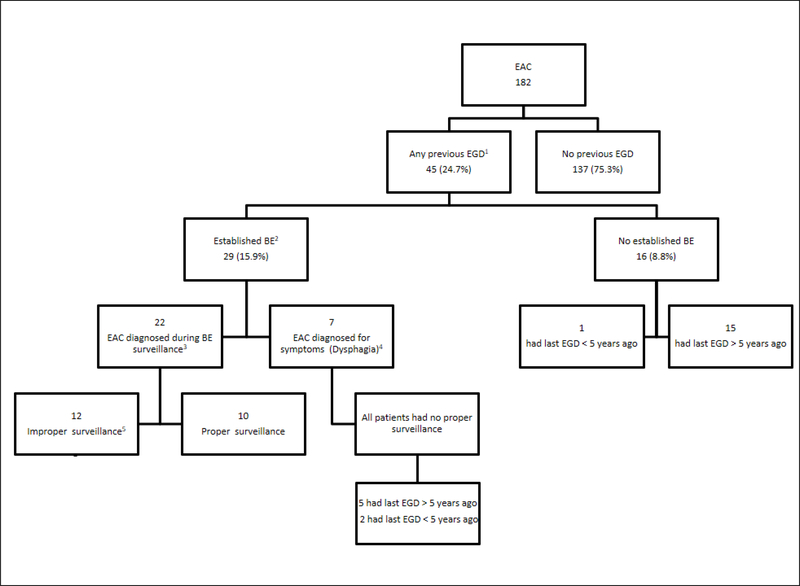

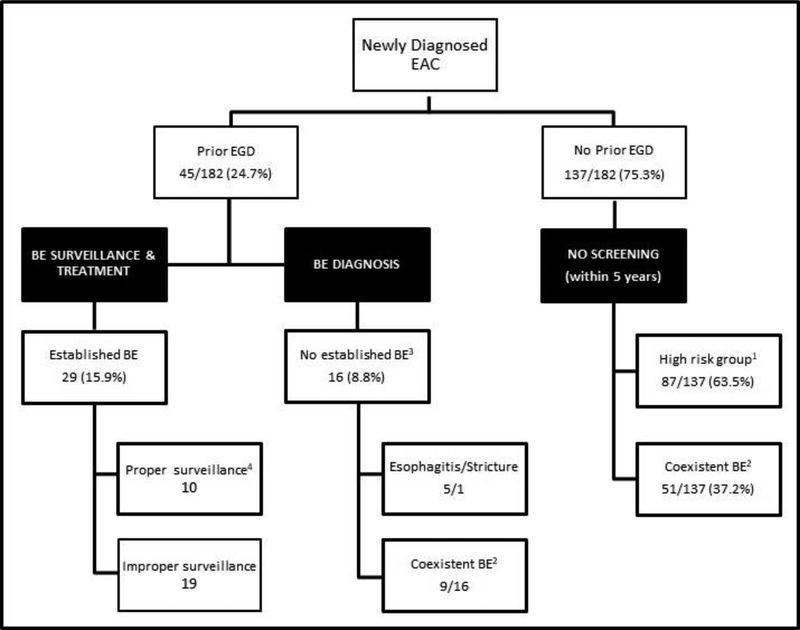

Notably, 137 (75.3%) patients did not have any EGD performed prior to their EAC diagnosing EGD (Figure 1). These patients’ charts were further examined to identify if there were any missed opportunities for BE screening (Figure 2). We found that 87 patients (63.5%) had a documented history of GERD, and of these 72 patients (82.7%) had GERD in addition to active or previous smoking history, 79 (90.8%) were Caucasian, and 68 (78.2%) had a BMI of 25 or more. Almost two thirds (63.5%) of this group were considered high risk for BE or EAC, but none had a prior EGD for screening. At time of EAC diagnosis, 51 of the 137 patients without a prior EGD (37.2%) had coexistent BE confirmed by histology and an additional 5 had salmon color mucosa suggestive of BE that was not biopsied (Figure 2).

Figure 1:

Flow Diagram of EAC patients.

Abbreviations: EAC: Esophageal adenocarcinoma. EGD: Esophagogastroduodenoscopy. BE: Barrett’s esophagus.

Definitions:

1:Previous EGD: Any prior EGD for any indication including screening and surveillance for BE.

2:Established BE: Patients with confirmed histological diagnosis of BE at least 6 months prior to the EAC diagnosis.

3:Proper surveillance: If the patient underwent appropriate surveillance EGD for BE based findings from previous endoscopies.

4:Patients had established BE, but they had the EGD performed to evaluate new symptoms (i.e. dysphagia, weight loss) rather than for BE surveillance.

5:Improper surveillance: Patients with established BE who did not have appropriate surveillance EGD for BE based on findings from previous endoscopies.

Figure 2:

Missed Opportunities for Screening and Surveillance for BE among patients diagnosed with EAC during 2005–2017.

Abbreviations: EAC: Esophageal adenocarcinoma. EGD: Esophagogastroduodenoscopy. BE: Barrett’s esophagus.

Definitions:

1:High risk group: Male patients over the age of 50 with GERD and at least one of the other risk factors like obesity, smoking use (active or former) or Caucasian ethnicity.

2:Coexistent BE: Patients with confirmed histological diagnosis of BE at the time of EAC diagnosis.

3:Established BE: Patients with confirmed histological diagnosis of BE at least 6 months prior to the EAC diagnosis.

4:Proper surveillance: If the patient underwent appropriate surveillance EGD for BE based findings from previous endoscopies.

Missed opportunity 2 (Missed BE diagnosis in those who had EGD)

Only 45 patients (24.7%) had an EGD performed after their first VA visit but prior to EAC diagnosis. Of these, 29 patients had a BE diagnosis established while the other 16 patients (8.8% of total) did not (Figure 1). Of the 16 patients with a previous EGD and no history of established BE, 15 had an EGD done greater than 5 years prior to their EAC diagnosis. Nine of these patients had coexistent BE at the EAC diagnosis, 6 had long segment BE (Figure 2). Severe erosive esophagitis was reported in 6 of those patients. None of these patients had a follow up EGD; 1 had a follow up EGD request but was a no show.

Missed opportunity 3 (Improper surveillance/treatment of BE in those with established BE)

Only 29 patients (15.9% of all EAC patients) had established BE prior to EAC diagnosis (Figure 1). Of these, 22 patients were diagnosed during a BE surveillance EGD; of whom only 10 (34.5%) had guideline concordant proper surveillance intervals and management of the BE while 19 (10.4% of total) did not (Figure 2). Lack of adherence to the proper interval timing for BE surveillance EGD due to patient (n=6) or system factors (n=6) was observed in the remaining 12 patients. Furthermore, 4 patients did not have appropriate eradication of BE with high grade dysplasia and 6 patients did not have representative sampling of the BE according to Seattle protocol during the prior endoscopies. In the other 7 of these 29 patients who did not have surveillance, the diagnosis of EAC was triggered by new onset of symptoms (mainly dysphagia and weight loss) and 5 of these patients were diagnosed with stage IV disease and 2 patients with stage III disease.

Temporal trends

The number and proportions of patients with established BE prior to a diagnosis of EAC over time is shown in Table 1. We found no evidence for a significant change over time in the percentage of EAC patients with prior established BE (unadjusted annual percent change=1.04, 95% CI 0.94–1.15; annual percent change adjusted for age and GERD diagnosis=1.03; 95% CI 0.93–1.14). There was no-significant change (1.12, 95% CI: 0.81–1.56) in prior established BE over 3-year period of the study (2005–2007; 2008–2010; 2011–2013; 2014–2017).

Table 1:

Temporal trends of patients with established BE prior to a diagnosis of EAC over time.

| Year | No of EAC | Any EGD | Any EGD < 5 years | Pre EAC established BE (n, %) | Surveillance detected EAC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 12 | 2 | 1 | 2 (16.6%) | 1 |

| 2006 | 14 | 2 | 2 | 2 (14.3%) | 2 |

| 2007 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 1 (9.1%) | 0 |

| 2008 | 12 | 4 | 3 | 3 (25%) | 2 |

| 2009 | 21 | 5 | 1 | 1 (4.8%) | 2 |

| 2010 | 14 | 4 | 2 | 2 (14.3%) | 1 |

| 2011 | 13 | 4 | 3 | 3 (23%) | 3 |

| 2012 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 1 (11.1%) | 1 |

| 2013 | 14 | 3 | 2 | 2 (16.6%) | 2 |

| 2014 | 13 | 2 | 0 | 2 (15.4%) | 0 |

| 2015 | 21 | 4 | 2 | 2 (9.5%) | 2 |

| 2016 | 11 | 3 | 3 | 2 (18.2%) | 2 |

| 2017 | 17 | 7 | 3 | 5 (29.4%) | 4 |

Abbreviations: EAC: Esophageal adenocarcinoma. EGD: Esophagogastroduodenoscopy. BE: Barrett’s esophagus.

Among EAC patients diagnosed during 2013–2017, the findings were similar to those in the overall cohort. Of 76 patients, 25% had prior EGD and 75% had no prior EGD. Some of the missed opportunities were improper BE surveillance in 8 (10.5% of total), 2 with erosive esophagitis and no follow up (2.6%), and 40 with no prior screening EGD in high risk groups (52.6%) (Supplemental Figure 1). The proportions for the same categories in the overall group (n=182) were 10.4%, 3.2% and 47.8% (Figure 2).

Determinants and outcomes of prior established BE

There were significant differences in the proportions of GERD diagnosis, PPI use, EGD < 5 years, stage at diagnosis and management modalities between EAC detected in patients with or without prior established BE (Table 2). However, there were no significant differences in sex, race, BMI or smoking history between these two groups. The 29 EAC patients with prior established BE were more likely to be diagnosed with stage 0 or I disease (62.1% vs. 6.5%; p<0.001) and more likely to be managed with endoscopic and surgical modalities (62.1% vs 5.2%; p<0.001) than the 153 EAC patients without prior established BE (Table 2).

Table 2:

Clinical features of EAC patients with or without prior established BE.

| Variable | BE pre EAC | No BE pre EAC | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 29 | 153 | |

| Gender (M) | 29 (100%) | 152 (99.3%) | 0.999 |

| Age (year) Mean (SD) | 66.5 (10.8) | 67.5 (9.3) | 0.606 |

| <50 (ref) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.3%) | 0.492 |

| 50–70 | 17 (58.6%) | 105 (68.6%) | |

| >70 | 12 (41.4%) | 46 (30.1%) | |

| Race White (Ref) | 26 (89.7%) | 129 (84.3%) | 0.578 |

| Other | 3 (10.3%) | 24 (15.7%) | |

| EGD within 5 years | 23 (79.3%) | 1 (0.65%) | <0.001 |

| EGD ever | 29 (100%) | 16 (10.5%) | <0.001 |

| GERD diagnosis | 28 (96.6%) | 102 (66.7%) | 0.001 |

| BMI Mean (SD) | 30.9 (5.8) | 30 (6.5) | 0.467 |

| BMI <25 (Ref) | 2 (6.9%) | 22 (14.4%) | |

| BMI 25–30 | 10 (34.5%) | 50 (32.7%) | 0.218 |

| BMI >30 | 16 (55.2%) | 65 (42.5%) | |

| PPI use1 | 28 (96.6%) | 73 (47.7%) | <0.001 |

| Any Anti acid2 | 28 (96.6%) | 90 (58.8%) | <0.001 |

| Smoking Active | 9 (31%) | 66 (43.1%) | 0.757 |

| X-Smoker | 10 (34.5%) | 63 (41.2%) | |

| Stage 0 | 9 (31.04%) | 2 (1.3%) | <0.001 |

| I | 9 (31.04%) | 8 (5.2%) | |

| II | 3 (10.34%) | 37 (24.2%) | |

| III | 3 (10.34%) | 31 (20.3%) | |

| IV | 5 (17.24%) | 70 (45.8%) | |

| Uknown | 0 | 5 (3.3%) | |

| Management | <0.001 | ||

| Endoscopic3 | 13 (44.82%) | 3 (2%) | |

| Surgery alone | 5 (17.24%) | 5 (3.3%) | |

| Other4 | 11 (37.93%) | 125 (81.7%) | |

| None | 0 (%) | 20 (13%) | |

Abbreviations: EAC: Esophageal adenocarcinoma. EGD: Esophagogastroduodenoscopy. BE: Barrett’s esophagus. GERD: Gastroesophageal reflux disease. BMI: Body mass index. PPI: Proton pump inhibitors.

Definitions:

:PPI use: Use of a PPI therapy for GERD prior to EAC diagnosis

:Any Anti acid: Use of a PPI, Histamine-2 receptor blocker, or over-the-counter medications like Tums

:Endoscopic: Endoscopic therapy for early EAC lesions by endoscopic mucosal resection or endoscopic submucosal dissection.

: Other: chemoradiation with or without surgery.

DISCUSSION

In this study we identified 182 patients diagnosed with EAC at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston, Texas over a period of 13 years. Approximately half (89/182) had coexistent biopsy proven BE at the time of their EAC diagnosis. However, only 15.9% (29/182) had established BE prior to EAC diagnosis, and 9.9% (18/182) were detected in a surveillance EGD. The number and proportions of patients with established BE prior to EAC diagnosis did not change over time. Among patients with no prior established BE, most (63.5%) had not had any screening endoscopy despite the presence of GERD with multiple risk factors for BE and EAC risk, and the rest (8.8%) had missed opportunities to diagnose or treat BE.

Our study shows that screening for BE is the biggest potential opportunity to prevention or early detection of EAC. Despite the fact that almost two-thirds of our EAC patients were considered high risk for BE, 75% of patients did not have a prior screening EGD. While endoscopic screening for BE in the general population of patients with GERD who do not have additional risk factors is generally not recommended [5,6], there is limited retrospective evidence to support the benefit of the BE screening programs on EAC related mortality, particularly in high risk groups [9]. Several studies and models have tried to define high-risk individuals for EAC who might benefit from cost-effective targeted screening strategies [10, 11]. Male gender, white race, smoking status, age over 50 years, high BMI, symptomatic GERD for 5 or more years, and use of anti-reflux medications were the strongest predictors for increased risk of EAC [10, 11]. Given its predominantly male population, the VA has a significant population who meet criteria for endoscopic screening for BE. Further efforts ensure that high risk BE patients are recognized and scheduled for screening endoscopies are needed to be able to correct this missed opportunity. Considerations should be given to screening studies at the VA possibly using tools such as Cytosponge. In addition, VA primary care may need additional education as well as referral facilitation for high-risk GERD patients who may benefit from BE screening.

The second missed opportunity (8.8%) was not recognizing the presence of BE among previous upper endoscopies in high-risk patients. Almost one third of the patients in this group had a history of severe esophagitis and a follow-up endoscopy was not performed to evaluate for underlying BE, although the consequences of follow up are uncertain.One retrospective study found that BE was detected in up to 9% of patients with prior erosive esophagitis and BE was detected exclusively on follow-up endoscopies [12].

The third missed opportunity (10.4%) was failure to properly survey and eradicate dysplastic BE in those with established BE prior to EAC diagnosis. This was due to patient’s factors (mainly, failure to follow up) or system factors. Centralized patient registries, dedicated BE clinics and interventions to improve patient adherence are needed. Our study showed that patients with EAC diagnosed during BE surveillance program were more likely to be diagnosed in early stages (0 and 1) and more likely to be managed with endoscopic and surgical modalities compared to those patients who did not have established BE prior to their EAC diagnosis or who had endoscopy triggered by onset of new symptoms. These results are consistent with previously published studies [8]. Therefore, following proper surveillance protocol should be emphasized in patients with BE to allow for early detection and prevention of EAC.

The strengths of this study include a relatively large cohort of EAC patients in a semi-closed healthcare system. Moreover, this study represents the first study highlighting the proportion of EAC patients who had possible missed opportunities for screening and surveillance of BE. Due to limited documentation, we could not identify the exact system related factors that lead to failure of proper surveillance and treatment of established BE prior to EAC. We also did not examine EAC mortality or cost effectiveness of screening or surveillance.

In summary, lack of screening prior to the EAC diagnosis represents the biggest missed opportunity for prevention and early detection of EAC. Developing and adhering to a cost-effective screening protocol targeting high-risk individuals should be the first priority.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1: Missed Opportunities for Screening and Surveillance for BE among patients diagnosed during 2013–2017.

Acknowledgments

Financial disclosure: None to report.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding this paper.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Thrift AP and Whiteman DC, The incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma continues to rise: analysis of period and birth cohort effects on recent trends. Annals of Oncology, 2012. 23(12): p. 3155–3162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rustgi AK and El-Serag HB, Esophageal Carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine, 2014. 371(26): p. 2499–2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thrift AP, The epidemic of oesophageal carcinoma: Where are we now? Cancer Epidemiology, 2016. 41: p. 88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maret-Ouda J, El-Serag HB, and Lagergren J, Opportunities for Preventing Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Prevention Research, 2016. 9(11): p. 828–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaheen NJ, et al. , ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Barrett’s Esophagus. The American Journal Of Gastroenterology, 2015. 111: p. 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement on the Management of Barrett’s Esophagus. Gastroenterology, 2011. 140(3): p. 1084–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muthusamy VR, et al. , The role of endoscopy in the management of GERD. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 2015. 81(6): p. 1305–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Serag HB, et al. , Surveillance endoscopy is associated with improved outcomes of oesophageal adenocarcinoma detected in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut, 2016. 65(8): p. 1252–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saxena N and Inadomi JM, Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Endoscopic Screening and Surveillance. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Clinics of North America, 2017. 27(3): p. 397–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thrift AP, et al. , A Model to Determine Absolute Risk for Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 2013. 11(2): p. 138–144.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shao-Hua X and Jesper L, A model for predicting individuals’ absolute risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma: Moving toward tailored screening and prevention. International Journal of Cancer, 2016. 138(12): p. 2813–2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Modiano N and Gerson LB, Risk factors for the detection of Barrett’s esophagus in patients with erosive esophagitis. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 2009. 69(6): p. 1014–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1: Missed Opportunities for Screening and Surveillance for BE among patients diagnosed during 2013–2017.