Abstract

NKG2D ligands are widely expressed in solid and hematologic malignancies but absent or poorly expressed on healthy tissues. We conducted a phase 1 dose-escalation study to evaluate the safety and feasibility of a single infusion of NKG2D-chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells, without lymphodepleting conditioning in subjects with acute myeloid leukemia/myelodysplastic syndrome or relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Autologous T cells were transfected with a γ-retroviral vector encoding a CAR fusing human NKG2D with the CD3ζ signaling domain. Four dose levels (1×106–3×107 total viable T cells) were evaluated. Twelve subjects were infused (7 AML, 5 MM). NKG2D-CAR products demonstrated a median 75% vector-driven NKG2D expression on CD3+ T cells. No dose-limiting toxicities, cytokine release syndrome, or CAR T cell–related neurotoxicity was observed. No significant autoimmune reactions were noted, and none of the ≥ Grade 3 adverse events were attributable to NKG2D-CAR T cells. At the single injection of low cell doses employed in this trial, no objective tumor responses were observed. However, hematologic parameters transiently improved in one subject with AML at the highest dose, and cases of disease stability without further therapy or on subsequent treatments were noted. At 24 hours, the cytokine RANTES increased a median of 1.9-fold among all subjects and 5.8-fold among 6 AML patients. Consistent with preclinical studies, NKG2D-CAR T cell–expansion and persistence were limited. Manufactured NKG2D-CAR T cells exhibited functional activity against autologous tumor cells in vitro, but modifications to enhance CAR T-cell expansion and target density may be needed to boost clinical activity.

Keywords: NKG2D-ligands, CAR T cells, acute myeloid leukemia, multiple myeloma

Introduction

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy can induce remarkable clinical remissions in refractory B-cell lineage leukemias and lymphomas (1–6). However, clinical success targeting non–B-cell antigens has been limited, and novel strategies to target acute myeloid leukemia (AML), multiple myeloma (MM), and solid tumors are needed. Here, we report results from a first-in-human phase 1 trial using CAR-expressing autologous T cells targeted against NKG2D ligands in adult patients with AML/myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and relapsed/refractory myeloma. Both the CAR structure and nature of the targeted antigens were distinct from CAR approaches in previous clinical trials. Rather than incorporating single-chain fragment immunoglobulin variable regions, this CAR used the naturally occurring NKG2D receptor as the antigen-binding domain, fused to the intracellular domain of CD3ζ. A γ-retroviral vector was used to express the NKG2D-CAR, relying on endogenous Dap10 expression and colocalization to provide a costimulatory signal (7). NKG2D is an activating receptor expressed on NK cells, invariant NKT cells, γδ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and a small fraction of CD4+ T cells. NKG2D forms a homodimer and associates with the adaptor molecule Dap10 in the transmembrane domain to form a hexameric complex that mediates its function in T cells via recruitment of the p85 PI3-kinase and Vav-1 signaling complex (8). In its native form, NKG2D provides a costimulatory signal to T cells but relies on antigen recognition via the T-cell receptor (TCR) to deliver the primary activating signal (7). In contrast, NKG2D ligand recognition through the NKG2D-CAR mediates primary T-cell activation.

NKG2D is highly conserved and recognizes a group of eight ligands, namely MICA, MICB, and the UL16-binding proteins (ULBP) 1–6. NKG2D ligands are upregulated in response to DNA damage, infection with certain pathogens, and importantly, malignant transformation (7). NKG2D ligand expression has been reported in a broad range of solid tumors and hematologic malignancies, including AML and MM, whereas ligands are generally absent on healthy tissues (9–14). Thus, NKG2D-based CAR T cells have the potential for broad oncologic applications. Murine studies by Sentman and colleagues demonstrate NKG2D-CAR T-cell efficacy in eradicating established MM, lymphoma, and ovarian cancers and the induction of autologous immunity protective against tumor re-challenge, even after NKG2D-CAR T cells were no longer detectable (15–21). NKG2D-CAR T cells have also been shown to inhibit the growth of tumors with heterogeneous NKG2D ligand expression (22). Importantly, human NKG2D-CAR T cells do not react to autologous peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or bone marrow (BM) from healthy donors in vitro (16). Nevertheless, concern for ligand upregulation on healthy tissues and induction of an inflammatory feedback loop under conditions of cell stress is justified. Analogous to cytokine release syndrome (CRS), which has been observed in CAR T-cell clinical trials, dose- and strain-dependent NKG2D-CAR toxicity was associated with production of inflammatory cytokines in murine models (23,24). Therefore, this trial was designed emphasizing safety parameters. Lymphodepleting chemotherapy, which was not required for efficacy in murine models, was not employed to minimize the risk of NKG2D ligand induction on healthy tissues. Dose-escalation started at a single low dose of 1 × 106 viable T cells. In this first-in-human trial, we demonstrated the feasibility and safety of infusion of freshly manufactured autologous NKG2D-CAR T cells in AML and MM patients up to a dose of 3 × 107 T cells. Observations of transient hematologic improvement and unexpected disease stability in some patients, as well as demonstration of CAR T-cell activity against autologous tumor cells in vitro, support further development of this approach.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

This single-center phase 1 study was conducted as per the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines and approved by the FDA, the Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee and the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center institutional review board, #NCT02203825 (www.clinicaltrials.gov). All patients provided written informed consent. Eligible subjects were ≥18 years old with AML or MDS, not in remission and without standard treatment options, or relapsed/refractory MM with measurable and progressive disease after prior therapy with an immunomodulator and proteasome inhibitor. Notable exclusion criteria included central nervous system (CNS) involvement, active infections, uncontrolled medical disorders, active autoimmune disease, prior disease-directed therapy within 3 weeks of T-cell infusion, and prior allogeneic stem cell transplantation (SCT), gene therapy, or adoptive T-cell therapy. Infusion criteria included absence of fever, active infection, and rapid disease progression. Products were infused in patients after administration of acetaminophen 650 mg by mouth and diphenhydramine 25–50 mg by mouth or intravenously. A modified Fibonacci “3+3” dose escalation design of a single infusion of NKG2D-CAR T cells ranging from 1×106 to 3×107 total viable CD3+ T cells across 4 dose levels was followed, with the provision to enroll at least 1 patient with AML/MDS and MM in each 3-patient cohort.

The primary endpoints included evaluating the safety and feasibility of a single intravenous infusion of freshly manufactured NKG2D-CAR T cells without lymphodepleting conditioning. Feasibility was defined by the frequency of enrolled subjects who did receive NKG2D-CAR T cells. Safety was defined by the absence of NCI CTCAE v4.0 ≥ Grade 3 events or Grade 2 autoimmune events with possible, probable, or definite attribution to NKG2D-CAR T cells. Secondary endpoints included progression-free survival, clinical antitumor effects, and immunologic correlatives. Objective tumor response rates were monitored according to the Myeloma IMWG Uniform Response Criteria, MDS IWG Response Criteria, and revised “Cheson” criteria for AML, respectively, with the initial response assessment at day 28 (25–28). Stable disease was not an endpoint defined for subjects with AML in the original trial design (29). To obtain samples for safety, efficacy, and immunologic analyses, patients underwent collection of plasma and peripheral blood samples at prospectively defined timepoints such as pre-infusion, 1 and 24 hours following infusion, weekly until 28 days following infusion then monthly as relevant, as well as bone marrow sampling and repeat imaging pre-infusion, 28 days, and 3 months as relevant.

Clinical γ-retroviral vector and cell product manufacture and analysis

Construct design

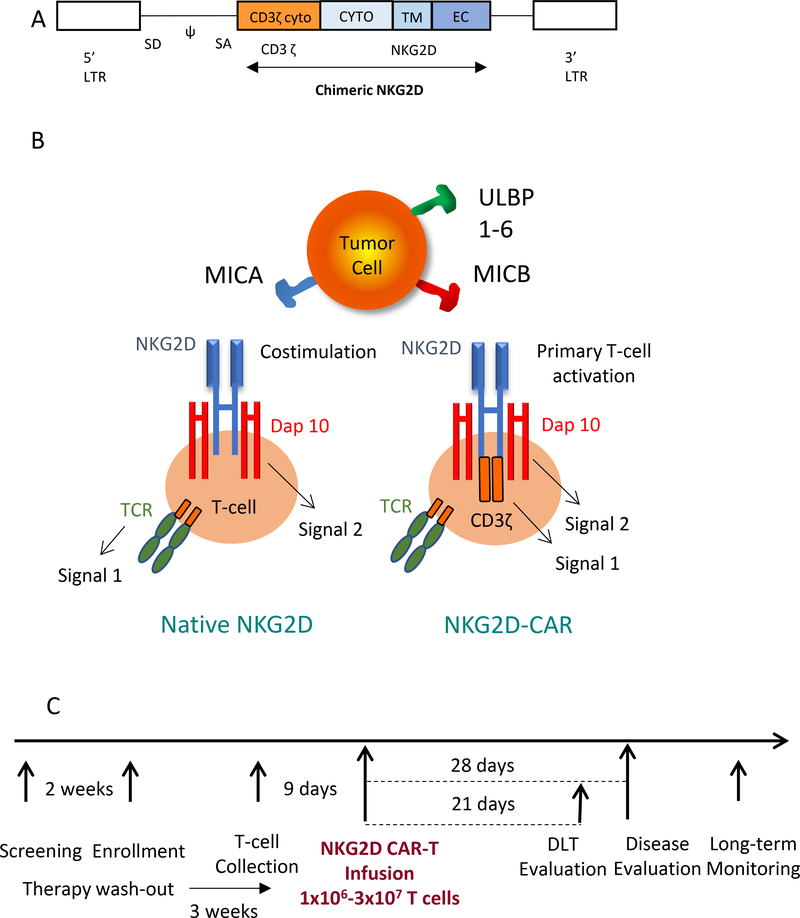

The NKG2D-CAR gene (chNKG2D) was created by fusing the human cytoplasmic CD3ζ coding sequence to the full-length human NKG2D gene (KLRK1)(30) (Fig. 1A). (Sequence of NKG2D CAR transgene: (CD3zeta cytoplasmic domain underscored; NKG2D gene bold)

Figure 1: NKG2D-CAR concept and trial design.

A) Full-length NKG2D with preserved extracellular (EC), transmembrane (TM), and cytoplasmic domain (CYTO) were fused to the cytoplasmic domain of the CD3ζ chain to create the NKG2D-CAR and cloned into the SFG vector. B) In T cells, recognition of NKG2D ligands by native NKG2D provides co-stimulation via Dap10 signaling but relies on primary T-cell activation through the TCR. In NKG2D-CAR T cells, the CAR directly activates NKG2D-CAR T cells through binding of MICA, MICB, or the UL-16 binding proteins (ULBP) 1–6 on tumor cells, independent of the TCR, and receives a costimulatory signal through the preserved transmembrane interaction with Dap10. C) Trial schema indicates a 3-week washout period from prior therapy, 9-day manufacturing process, infusion of freshly manufactured T cells according to dose level, DLT evaluation at 21 days, and response evaluation at 28 days after infusion.

ATGAGAGTGAAGTTCAGCAGGAGCGCAGACGCCCCCGCGTACCAGCAGGGCCAGAACCAGCTCTATAACGAGCTCAATCTAGGACGAAGAGAGGAGTACGATGTTTTGGACAAGAGACGTGGCCGGGACCCTGAGATGGGGGGAAAGCCGCAGAGAAGGAAGAACCCTCAGGAAGGCCTGTACAATGAACTGCAGAAAGATAAGATGGCGGAGGCCTACAGTGAGATTGGGATGAAAGGCGAGCGCCGGAGGGGCAAGGGGCACGATGGCCTTTACCAGGGTCTCAGTACAGCCACCAAGGACACCTACGACGCCCTTCACATGCAGGCCCTGCCCCCTCGCGAATTCGGGTGGATTCGTGGTCGGAGGTCTCGACACAGCTGGGAGATGAGTGAATTTCATAATTATAACTTGGATCTGAAGAAGAGTGATTTTTCAACACGATGGCAAAAGCAAAGATGTCCAGTAGTCAAAAGCAAATGTAGAGAAAATGCATCTCCATTTTTTTTCTGCTGCTTCATCGCTGTAGCCATGGGAATCCGTTTCATTATTATGGTAGCAATATGGAGTGCTGTATTCCTAAACTCATTATTCAACCAAGAAGTTCAAATTCCCTTGACCGAAAGTTACTGTGGCCCATGTCCTAAAAACTGGATATGTTACAAAAATAACTGCTACCAATTTTTTGATGAGAGTAAAAACTGGTATGAGAGCCAGGCTTCTTGTATGTCTCAAAATGCCAGCCTTCTGAAAGTATACAGCAAAGAGGACCAGGATTTACTTAAACTGGTGAAGTCATATCATTGGATGGGACTAGTACACATTCCAACAAATGGATCTTGGCAGTGGGAAGATGGCTCCATTCTCTCACCCAACCTACTAACAATAATTGAAATGCAGAAGGGAGACTGTGCACTCTATGCATCGAGCTTTAAAGGCTATATAGAAAACTGTTCAACTCCAAATACATACATCTGCATGCAAAGGACTGTGTAA

NKG2D is a type II protein in which the NH2 terminal is located intracellularly, whereas CD3ζ is a type I protein with the COOH terminal in the cytoplasm. Therefore, the CD3ζ cytoplasmic domain, containing its three ITAMs was fused to NKG2D in reverse orientation (COOH-terminal of CD3ζ to NH2-terminal of NKG2D), as described (20), and then cloned into the Moloney murine leukemia virus-based γ-retroviral vector SFG, received from the laboratory of Dr. Gianpietro Dotti (Baylor College of Medicine) with the permission of Dr. Richard Mulligan (Harvard Medical School) (31). Upon expression, the orientation of the CD3ζ chain was in an inverted orientation as part of the CAR. No signal peptide was required for CAR expression, given that NKG2D is a type II protein.

By using full-length NKG2D, colocalization with endogenously expressed Dap10 in the transmembrane domain provides a costimulatory signal. Untransduced CD8+ T cells may receive a costimulatory signal via native NKG2D, but they require a primary activating signal through their TCR. In NKG2D-CAR–expressing T cells, recognition of NKG2D ligands via the CAR mediates primary T-cell activation, independent of the endogenous TCR and provides a costimulatory signal via endogenously expressed Dap10 (Fig. 1B).

Cells and cell lines

PG13 producer lines were generated under cGMP conditions by repeated transduction with transient retroviral supernatant obtained from a Phoenix-Eco packaging cell line transfected with SFG-chNKG2D vector. Clinical-grade high-titer viral supernatant was produced from a PG13 SFG-chNKG2D clone at Rimedion (Indiana University), per cGMP procedures. RPMI 8866 (95041316) and K562 (CRL-3344) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and P815 (TIB-64) from ATCC prior to the performance of the experiments. Cells lines were passaged at the recommended ratios and used between the passages of 3 and 30. Cultures were regularly checked for mycoplasma contamination by Q-PCR using MycoSeq (Thermofisher).

Manufacturing process

Autologous peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were obtained by peripheral venipuncture (~120 mL) or non-mobilized apheresis guided by an absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) threshold of 0.6K cells/μL, followed by Ficoll-isolation (GE Healthcare). Cell manufacturing occurred over 9 days in the Dana-Farber Cell Manipulation Core Facility under cGMP conditions (Fig. 1C). Fresh PBMCs were seeded at 1 × 106 cells/mL with interleukin 2 (IL-2; 100 IU/mL; Proleukin, Bayer HealthCare) and OKT3 (40 ng/mL; MACS GMP CD3 pure, Miltenyi Biotec) for 48 hours in X-Vivo 15 medium (Lonza) supplemented with 5% human AB serum (Gemini Bio-products) and 2 mM L-glutamine (Lonza) in T75 cm2 cell culture flasks (Nunc). Activated cells were then transduced twice with clinical grade SFG-chNKG2D retrovirus supernatant in retronectin-coated (Retronectin (GMP), Takara BIO Inc) 24-well plates (Cellstar Greiner Bio-one) in the presence of IL-2 (100 IU/mL) on days –6 and –5. 18–24 hours after the last transduction, cells were transferred into G-Rex flasks (Wilson Wolf) in complete X-Vivo 15 supplemented with IL-2 (100 IU/mL). Cells were fed with additional fresh complete X-Vivo 15 with IL-2 (100 IU/mL) on day –2, and transduced T cells were harvested after approximately 48 additional hours of culture. Cells were resuspended in Plasmalyte (Baxter) supplemented with 1% human Albumin (Grifols), counted using trypan blue, and infused fresh. Release criteria included ≥70% viability, ≥5% CD8+ T-cell transduction efficiency, negative testing for endotoxin (<5EU/kg/hr), negative gram stain (analyzed on day of release), and ≤5 vector copy number (VCN)/cell and negative PCR testing for mycoplasma (a sample of cells was obtained on day –1 prior to harvest for analysis and analyzed by Q-PCR using MycoSEQ (Thermofisher). The manufacturing process is comprehensively detailed separately(32).

Flow cytometry of manufactured products

Products were characterized using standard flow cytometry techniques to determine surface expression of T-, B-, NK, myeloid, and plasma cell and T-cell differentiation markers with 4 panels including combinations of the following fluorophore-conjugated anti-human monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) (Supplementary Table S1): a) NKG2D expression: CD3, CD4, CD8, CD314 (NKG2D); b) Myeloid cells: CD34, CD14, CD33, CD11b; c) T-, B-, and NK-cells: CD45, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD19, CD16, CD56; d) Plasma cells: CD38, CD138, CD3, CD19. Cells were acquired on a BD FACS Canto Flow cytometer and analyzed using BD FACS Diva Version 6.1.3 (BD Biosciences). Native NKG2D has high expression and is indistinguishable by surface staining from NKG2D-CAR expression on CD8+ T cells (7). We, therefore, established a threshold of NKG2D surface fluorescence intensity, exceeded by only 5% of CD8+ T cells in a mock-treated autologous T-cell culture and measured transduction efficiency based on the percentage of CD8+ T cells exceeding this threshold for each patient. Transduction efficiency in CD4+ T cells was measured relative to isotype controls (Supplementary Fig. S1). Aliquots of end-of-manufacturing samples were cryopreserved and subsequently stained with the following anti-human mAbs to determine the T-cell differentiation state of the infused product using standard staining techniques: CD45RO, CD3, CD4, CD8, CCR7, CD314, acquired on a BD FACS Canto Flow cytometer and analyzed using FACS Diva Version 8.0.1 (BD Biosciences).

Standard extracellular protein staining techniques

Staining on NKG2D-CART cell-products was performed directly after harvest from culture for release testing and on thawed, cryopreserved product for T-cell differentiation markers. For staining of patient samples, whole blood was incubated in RBC lysis buffer (eBioscience). All cells were then washed twice in PBS +/− 2% FCS, and patient samples and fresh final product incubated with Fc receptor block (Miltenyi) at 4°C prior to staining. After incubation with relevant monoclonal antibodies (Supplementary Table S1) at 4°C, cells were washed with PBS +/− 2% FCS and if relevant, were fixed using Cytofix (BD) prior to analysis.

Vector copy number (VCN) and replication competent retrovirus (RCR) testing

To determine VCN, the retroviral DNA sequence was monitored by Q-PCR in samples of total DNA using primers and a labeled probe (Integrated DNA Technologies) specific for the fusion region of the NKG2D CAR construct. One million cells were processed for DNA extraction using Blood and Cell Culture DNA kit (Qiagen) and 100 ng of DNA was used in each reaction, using SsoAdvanced Universal Probes Supermix (BioRad) on a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) with rapid temperature ramp speed in a validated assay. The primer and probe sequences were as follows: forward primer (5’-GCCACCAAGGACACCTAC-3’), reverse primer (5’-CTCATCTCCCAGCTGTGTC-3’), probe (5’-[FAM]-AATTCGGGTGGATTCGTGGTCGG-[BHQ]-3’). The probe was labeled at the 5’ end, as indicated, with 6-FAM, and 3’ Black Hole Quencher (IDT).

To determine copy number per unit DNA, a 7-point standard curve was generated consisting of 10–1×106 copies of SFG.NKG2D-CAR plasmid DNA spiked into 100 ng non-transduced genomic DNA. Each data point (sample, standard curve) was obtained in quadruplicate. Pass/fail parameters were based on pre-stablished acceptance ranges for assay performance derived from qualification studies and included r2 values, amplification efficiency, absence of potential amplification in healthy donor DNA, and ability to accurately quantify known amounts of plasmid DNA spiked into genomic DNA within a predefined result range. The following formula was used to control for outlier CT values among quadruplicates: . Data points with a Z value > 1.1 were discarded (33). The lower limit of quantification for the assay was 30 copies/100 ng DNA. Copy number per cell was determined based on the following formula: average VCN/cell= (copies/ng DNA in the reaction) x (total ng DNA/cell number).

For RCR testing, DNA was isolated from the 1 × 106 NKG2D CAR product T-cells, as well as 15 mL of T-cell supernatant from CAR T-cell product cultures at day –1 as described above. Primers (IDT) used were GALV5’II: 5’-ACCACAGGCGACAGACTTTTT-3’ and GALV3’II: 5’-TGAGACAGCCTCTCTTTTAGTCCT-3’. PCR-certified water and PG13 DNA were used as negative and positive controls (500 bp for the GALV gene amplification), respectively, and cells and cell supernatant from NKG2D CAR T-cell cultures were evaluated for the presence of this gene. PCR reactions were run under the following conditions: 95°C denaturation, 65°C annealing, and 72°C extension for a total of 35 cycles. Amplified samples were analyzed on a 1% agarose gel in 1XTAE SyberSafe (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and visualized under UV light. Samples were then evaluated for the presence or absence of a 500 bp band, characteristic of GALV protein (34).

NKG2D-CAR T-cell function by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Concurrent with NKG2D-CAR product release and infusion, in vitro functional activity was assessed by coculture of 100,000 clinical grade NKG2D-CAR T cells with 100,000 autologous patient PBMCs or BM cells (cryopreserved prior to infusion and involved by underlying AML or MM) or with healthy donor PBMCs, RPMI 8866, K562, or P815 cells at a 1:1 ratio for 24 hours. Cells were cultured in complete X-Vivo media (Lonza) in 96-well round bottom plates (Corning). NKG2D-CAR T cells or mock-treated T cells were incubated with purified anti-human CD314 (NKG2D, 20 μg/mL, clone 1D11; BD) or isotype antibody (20 μg/mL) for 15 minutes prior to coculture. Cell-free media was harvested and concentrations of IFNγ determined by ELISA (IFNγ Duoset Elisa, R&D systems).

Analysis of patient samples following NKG2D-CAR T-cell infusion

NKG2D CAR transgene and RCR detection by PCR

To quantify NKG2D-CAR transgenes and RCR present in peripheral blood (PB) and/or bone marrow (BM), genomic DNA was extracted from cryopreserved PB or BM aspirate samples using QIAamp DNA blood extraction kits (Qiagen), quantified by spectrophotometer, and stored at –80C. Q-PCR analysis on genomic DNA samples and data analysis was performed as described for VCN and RCR detection on the NKG2D-CAR product, with the sets of primers and probe used for each assay detailed below.

NKG2D CAR transgene detection: Forward primer (5’-GCCACCAAGGACACCTAC-3’), reverse primer (5’-CTCATCTCCCAGCTGTGTC-3’), probe (5’-[FAM]-AATTCGGGTGGATTCGTGGTCGG-[BHQ]-3’). Probe was labeled at the 5’ end, as indicated, with 6-FAM, and 3’ Black Hole Quencher (IDT)

RCR detection: Forward primer (5’- TCCGGAGACCATCAGTATCT −3’), reverse primer (5’- GGATAGTAATAGATGCGAGGAATCA −3’), probe (5’-[FAM]- CCCTTGCCTCTCCACCTCAGTTT-[BHQ]-3’). Probe was labeled at the 5’ end, as indicated, with 6-FAM, and 3’ Black Hole Quencher (IDT).

Circulating NKG2D-CAR T-cells and NKG2D ligand expression by flow cytometry

Standard whole blood flow cytometry techniques with combinations of the following anti-human mAbs were employed to monitor kinetics of NKG2D-CAR T cells in PB and BM, and NKG2D ligand expression on tumor cells: NKG2D, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD117, CD123, CD34, CD138, CD38, CD45, HLA-DR, CD33, MICA, MICB, ULBP1, ULBP2/5/6, ULBP3, and ULBP4 (Supplementary Table S1). Cells were acquired on a LSR Fortessa (BD Biosciences), and analysis performed using FlowJo software V10 (Treestar). Specific fluorescence indices (SFI) were calculated by dividing the median fluorescence intensity obtained with specific monoclonal antibodies by that of isotype controls.

ELISAs for soluble MICA and MICB

Soluble MICA and MICB in cell-free patient plasma were measured by ELISA using human MICA and MICB Elisa kits as per manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Scientific).

Analysis of cytokine secretion

To evaluate cytokines, 20 μL of patient plasma was diluted 1:1 with assay buffer and processed according to manufacturer’s instructions for the MILLIPEX MAP Human Cytokine/Chemokine Bead Panel (Millipore) at baseline and several time points after infusion for the following 41 cytokines: sCD40L, EGF, Eotaxin/CCL11, FGF-2, Flt-3 ligand, Fractalkine, G-CSF, GM-CSF, GRO, IFNα2, IFNγ, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL1ra, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12 (p40), IL-12 (p70), IL-13, IL-15, IL-17A, IP-10, MCP-1, MCP-3, MDC (CCL22), MIP-1α, MIP-1β, PDGF-AA, PDGF-AB/BB, RANTES, TGFα, TNFα, TNFβ, VEGF. Samples were run on the Bio-Plex 200 Suspension Array System (Bio-Rad). Standard curves were generated using human cytokine standards provided by the manufacturer (Millipore). Bio-Plex Manager V6.0 was used to analyze the data (Bio-Rad).

Statistical analysis

The maximum-tolerated dose (MTD) was defined as the highest T-cell dose at which ≤1 of 6 patients developed a dose-limiting toxicity (DLT). DLTs were defined as ≥Grade 3 toxicities not directly attributable to underlying disease or ≥Grade 2 autoimmune toxicity per NCI CTCAE v4.0, occurring within 21 days, at least possibly related to T-cell infusion and not controllable to ≤Grade1 within 72 hours. Patient and clinical characteristics were summarized as median and range for continuous variables and numbers and percentages for categorical variables. All reported toxicities, regardless of attribution, were summarized by type, maximum grade, and sorted by number of patients experiencing the toxicity. The maximum grade consolidates reports of a given toxicity for each patient over time. Overall survival (OS) was defined from the time of infusion to death or censored at the last known alive date. Spearman’s correction coefficient was used to summarize the correlation between ALC at time of infusion and maximum detected transgene level. Two-sample t tests were used to compare IFNγ production under specific conditions with nominal p-values reported; p<0.05 was considered significant. Analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Patient Characteristics

Fourteen patients consented. One patient died prior to initiating screening, and one enrolled patient became ineligible due to rapid disease progression prior to cell collection. Twelve patients had autologous T cells collected, received NKG2D-CAR T cells, and were evaluable. Median age was 70 years (range, 44–79 years), and 7 subjects had AML and 5 had MM. The median percentage of BM blasts on core biopsy in subjects with AML was 50% (range, 15–60%), with a median of 1 prior therapy (range, 0–4). Four AML patients had disease secondary to MDS, 3 had complex cytogenetics, 3 had TP53 mutations, 2 had FLT3 mutations (1 ITD, 1 TKD). All myeloma patients had undergone ≥5 therapies, including ≥1 autologous SCT. Three subjects had plasmacytomas with little marrow involvement. Median serum M-spike was 1.75g/dL (range, 0–3.16g/dL), and median urine M-spike was 256mg/24hrs. (range, 0–3969mg/24hrs.) (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S2).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic | No. (%) of patients (n=12) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| Median | 70 |

| Range | 44–79 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 9 (75%) |

| Female | 3 (25%) |

| Disease type | |

| AML | 7 (58%) |

| MM | 5 (42%) |

| AML characteristics | |

| FLT-3 ITD | 1 |

| TP53 mutation | 3 |

| FLT-3 TKD | 1 |

| Complex Cytogenetics | 3 |

| Secondary AML | 4 |

| Disease burden | |

| AML, marrow blasts (core), Median | 50% |

| Range | 15–60% |

| AML, # with peripheral blasts | 4 (57%) |

| AML, % peripheral blasts, Median | 8% |

| Range | 0–58% |

| MM, marrow plasma cells, Range | <5–80% |

| MM, FLC mg/dL, Median | 1524 |

| Range | 0–2615 |

| MM, Serum M-protein, Median | 1.75 g/dL |

| Range | 0–3.16 g/dL |

| MM, Urine M-protein, Median | 256mg/24h |

| Range | 0–3969mg/24h |

| MM, # with plasmacytomas | 3 (60%) |

| # Prior Regimens | |

| AML, Median | 1 |

| Range | 0–4 |

| MM | all ≥5 |

| MM, prior ASCT | all ≥1 |

| ALC, K/uL, Median | 0.58 |

| Range | 0.09–2.37 |

AML (Acute myeloid leukemia), MDS (Myelodysplastic syndrome), MM (Multiple Myeloma), FLC (free light chain ratio), ALC (Absolute Lymphocyte Count), ASCT (Autologous Stem Cell Transplant), ITD (Internal Tandem Duplication), TKD (Tyrosine Kinase Domain)

Feasibility of Manufacturing

Autologous PBMCs were obtained via peripheral venipuncture (n=5) or non-mobilized apheresis (n=7). All patients who underwent collection had CAR T-cell products successfully manufactured from initial fresh PBMCs and received NKG2D-CAR T cells at the protocol-specified doses. The CD4+/CD8+ composition was variable, with a median CD8+ T cells of 36% (range, 7–89%). Products were predominantly comprised of CD45RO+CCR7− T-effector memory (Tem) and CD45RO+CCR7+ central memory (Tcm) cells, with a median CD8+ Tem of 51% (range, 39–73%) and CD8+ Tcm of 36% (range 4–59%). The median VCN of the NKG2D-CAR transgene in the infused product was 0.61 copies/cell (range, 0.37–1.86), and the median transduction efficiency was 66% (range, 15–87%) on CD8+ T cells and 92% (range, 74–98%) on CD4+ T cells. Median NKG2D-CAR expression in the entire CD3+ compartment was 75% (range, 55–90%), resulting in median transduced T-cell doses of 7.38×105, 2.15×106, 6.92×106, and 2.45×107 in the respective dose cohorts (Table 2). AML blasts and CD38+CD138+ plasma cells were efficiently eliminated during the manufacturing process (median, ≤ 0.1% of live cells). In a single instance, CD19+ B cells persisted in both mock and transduced cultures (16% of live cells), expressed NKG2D after transduction, and were included in the infused product. This did not result in any clinical toxicities; workup, including an extensive leukemia/lymphoma flow panel, and viral testing was negative. Of the 12 patients, 11 received fresh NKG2D-CAR product immediately after harvest from manufacturing. For one patient, the product was stored at 4°C until resolution of respiratory symptoms, subsequently met viability criteria (≥70%), and was administered within 48 hours.

Table 2.

Cell product characteristics

| Cell Composition | Median | Range |

|---|---|---|

| CD8+ (among CD3+ cells) | 36% | 7–89% |

| Effector memory (among CD8+ cells) | 51% | 39–73% |

| Effector memory (among CD4+ cells) | 48% | 32–76% |

| Central memory (among CD8+ cells) | 36% | 4–59% |

| Central memory (among CD4+ cells) | 34% | 20–53% |

| Vector copy number/cell | 0.61 | 0.37–1.86 |

| NKG2D CAR+ (among CD8+) | 66% | 15–87% |

| NKG2D CAR+ (among CD4+) | 92% | 74–98% |

| NKG2D CAR+ (among CD3+) | 75% | 55–90% |

| # of transduced viable T-cells infused | ||

| Dose level 1 | 7.38×10e5 | 7.35–7.95 |

| Dose level 2 | 2.15×10e6 | 1.64–2.67 |

| Dose level 3 | 6.92×10e6 | 6.31–7.54 |

| Dose level 4 | 2.45×10e7 | 2.28–2.70 |

Effector memory (CD45RO+, CCR7-), Central memory (CD45RO+, CCR7+)

Safety and Clinical Outcomes

Products were infused inpatient after administration of acetaminophen and diphenydramine without prior lymphodepletion. No infusional toxicity, CRS, severe autoimmunity (specifically, no colitis or pneumonitis), CAR T cell–related encephalopathy syndrome (CRES), or death was observed. 120 adverse events (AEs) were reported: 18 (15%) grade 3 and 8 (7%) grade 4 (Supplementary Table S3). Of the grade ≥3 AEs, none were attributed to the NKG2D-CAR T cells but, rather, to underlying disease progression or infection. No DLTs were observed. Patient 8 (MM) had cryoglobulinemia preceding CAR T-cell infusion and experienced complications of hyper-viscosity syndrome with acute hearing loss and bilateral intracochlear bleeds, despite plasmapheresis (35,36). Events related to progressive plasmacytomas included cord compression, biliary obstruction and gastric erosion, and bleeding. None of the observed cases of parainfluenza (Day 19, Patient 1, AML), influenza A (Day 24, Patient 6, MM), and gram-negative biliary sepsis (Day 29, Patient 3, MM with prior peripancreatic plasmacytomas) prompted significant inflammatory or autoimmune symptoms besides fever. Patient 4 (MM) experienced new upper respiratory symptoms on the day of planned infusion. Out of concern for NKG2D ligand upregulation in bronchial epithelial cells under oxidative stress (37), cell infusion was delayed within a predefined 48-hour window until symptoms had resolved and a negative infectious work-up was confirmed. No subsequent respiratory complications occurred. Two patients, at dose level 4, developed a self-limited grade 1 follicular erythematous rash between 1 and 3 months after NKG2D CAR T-cell infusion. In Patient 12 (AML), this was deemed probably related to NKG2D-CAR T cells given concurrent improvements in hematologic parameters. Peripheral blood NKG2D-CAR transgene levels at that time were detectable at low levels. Skin biopsy revealed non-specific, mild spongiotic and interface dermatitis, with a very mild lymphocytic infiltrate. The rash resolved without systemic or topical steroids before additional skin sampling for Q-PCR detection of NKG2D-CAR sequences could be obtained, and the NKG2D-CAR transgene became undetectable in the peripheral blood thereafter.

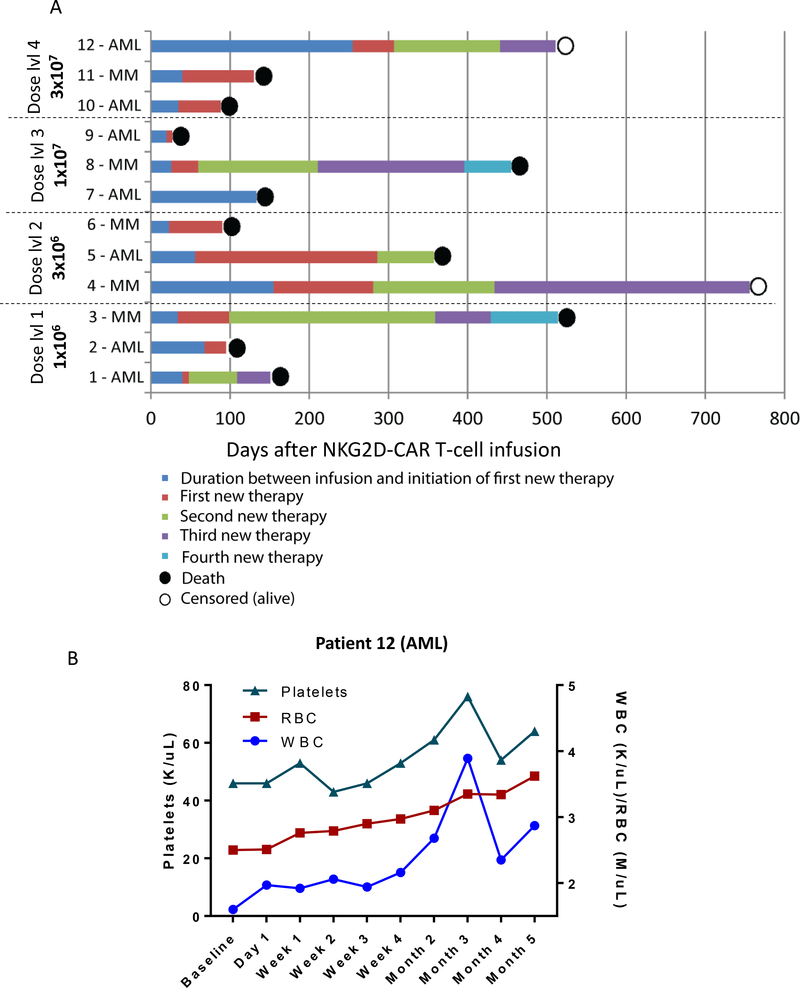

Objective clinical responses to NKG2D-CAR T-cell therapy alone, defined in the study protocol, were not seen, and all subjects received subsequent therapy (Fig. 2A). Three subjects (2 MM, 1 AML) started within 28 days of NKG2D-CAR T-cell infusion. Median overall survival (OS) was 4.7 months (range, 1.2–24.9+ months), with survival rates of 75% and 42% at 3 and 6 months, respectively. Two subjects remained alive at 16.8 months and 24.9 months, respectively. Patients 3, 4, and 8 (MM) exhibited disease stability for over one year on alternative therapies. Likewise, Patient 5 (AML), maintained stable disease for 6 months on an IDH-1 inhibitor trial despite a mutated allele frequency of <5% IDH and 54% p53 mutation burden at CAR T-cell infusion. Patient 7 (AML, dose level 3), with 50% BM blasts and a p53 mutation with allele burden of 80% at infusion, experienced resolution of B-symptoms, transient decrease in transfusion requirements, and had a 4.4-month survival without further therapy (Fig. 2A). Lastly, Patient 12 (AML, dose level 4) experienced improvement in hematologic parameters without further interventions (Fig. 2B), concurrent with development of a grade 1 skin rash and met the definition of “stable disease” at 3 months as defined by recent AML guidelines (29). He remained clinically stable for 6 months without further therapy and was alive at last follow-up on alternative treatment.

Figure 2: Patient Outcomes.

A) Swimmer’s plot indicating survival and time of subsequent therapies. B) Trajectory of peripheral blood counts in Patient 12 (AML) after NKG2D-CAR T-cell infusion.

Analysis of patient T-cell phenotypes, cytokines, and tumor ligand expression following infusion

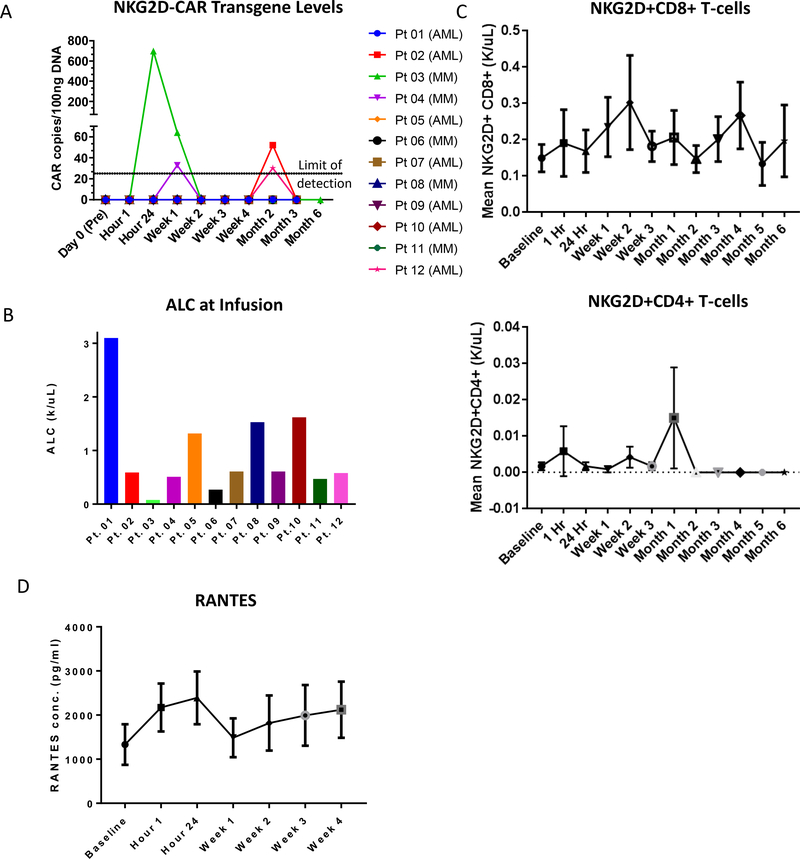

NKG2D-CAR T cells were transiently detected in four patients by Q-PCR in PB (AML, dose levels 1 and 4; MM, dose levels 1 and 2) (Fig. 3A), whereas analysis of BM at day 28 was negative for the NKG2D-CAR transgene in all evaluable patients (n=9). The highest transgene level was observed in Patient 3 (MM, dose level 1), with the lowest ALC at infusion (0.08K cells/μL) (Fig. 3B), and a trend towards an inverse correlation between ALC and transgene detection was noted (correlation efficient –0.54, p=0.07). Surface immunophenotyping of circulating lymphocyte subsets revealed no significant NKG2D-CAR T-cell expansion, measured by percentage of NKG2D+ cells among CD4+ T cells or absolute numbers of NKG2D+CD8+ or NKG2D+CD4+ T cells (Fig. 3C), but was limited by lack of a CAR-specific surface marker.

Figure 3: Detection and bioactivity of NKG2D-CAR T cells in peripheral blood.

A) NKG2D-CAR DNA at timepoints indicated on the horizontal axis as measured by Q-PCR. B) Absolute lymphocyte counts at time of infusion. Color scheme for patients is identical in panels A and B. C) Monitoring of absolute numbers of NKG2D+ CD8+ and CD4+ T cells using flow cytometry (n=12, Mean±SEM). D) RANTES detected (n=11, Mean±SEM).

Plasma cytokines were monitored by Luminex. Except for one AML patient with undetectable RANTES concentrations (Patient 09, dose level 3), all evaluated patients (n=11) demonstrated an increase in RANTES within 3 weeks of NKG2D-CAR T-cell infusion (Fig. 3D). At 24 hours, the median fold-increase was 1.8 (range, 0–865) among all patients, with a median fold-increase of 5.8 (range, 1.64–865) among the six AML patients with detectable concentrations.

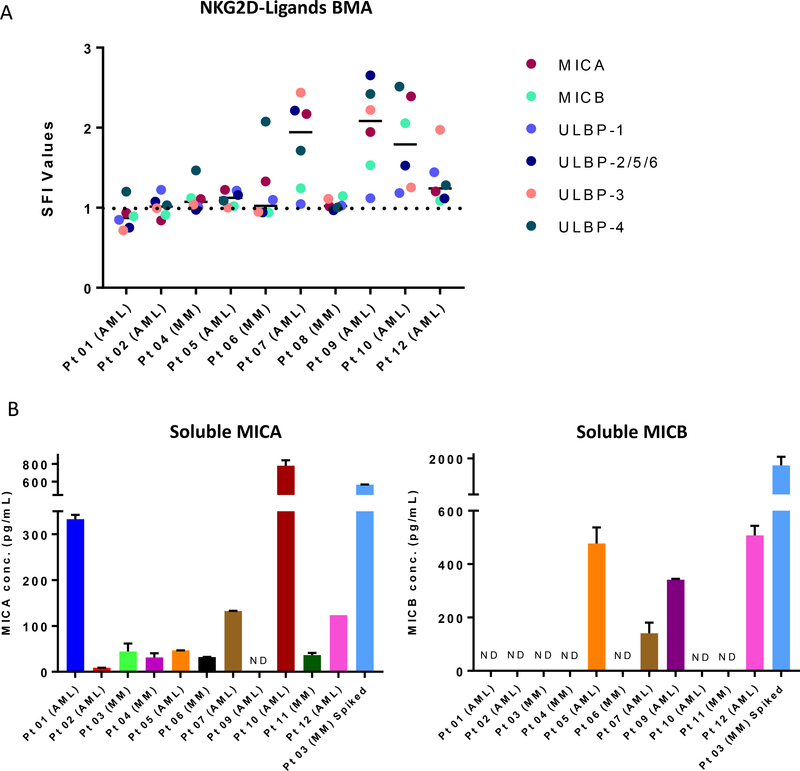

NKG2D ligand expression on patient AML blasts or MM plasma cells derived from pre-treatment BM samples was evaluated by flow cytometry. Although ligand expression was relatively low, all 10 evaluable patients demonstrated an SFI >1.0 for at least one ligand. Consistent with other studies (14), co-expression of multiple ligands was observed (Fig. 4A). Soluble MICA in plasma was detected in 10 and MICB in 4 of 11 assayed patients prior to NKG2D-CAR T-cell infusion (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4: NKG2D-ligand expression and soluble ligands.

A) Surface NKG2D ligand detection in AML blasts (7 AML patients) and MM cells (3 MM patients) in bone marrow aspirates (BMA) at baseline measured by flow cytometry (SFI>1 indicates ligand expression exceeding isotype). AML blasts: live/CD45dim cells expressing patient-specific AML markers including CD117, CD123, CD33, and HLA-DR. MM cells: live/CD138+CD38+ cells. B) Detection of soluble MICA and MICB in patient plasma at baseline using ELISA. Plasma of Patient 3 (MM) was separately spiked with soluble MICA and MICB as an internal positive control. ND: not detectable.

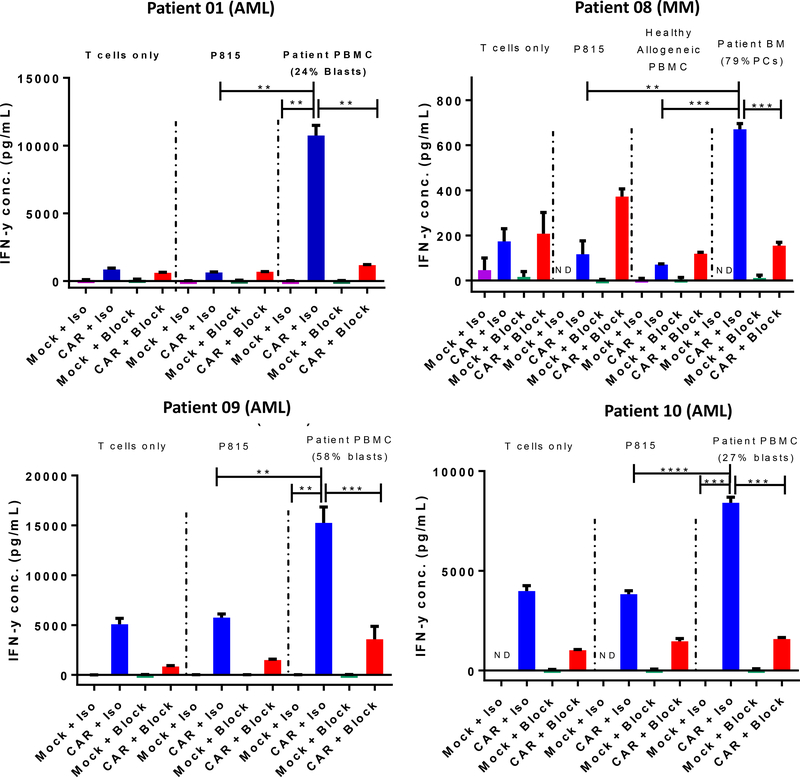

NKG2D-CAR T cells from all tested products (n=11) produced IFNγ during coculture with NKG2D ligand-expressing cell lines RPMI8886 and K562, but not the ligand-negative line P815. In select patients, paired samples were available to assess in vitro function of NKG2D-CAR T-cell products against autologous tumor (n=4). Coculture resulted in significant IFNγ production by NKG2D-CAR T cells in response to autologous tumor-containing PBMCs or BM but not to ligand-negative cell lines or healthy donor PBMCs. This effect was NKG2D-specific, as it was abrogated by preincubation of CAR T cells with a NKG2D-blocking mAb but not isotype control (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Functional activity of NKG2D-CAR T cells against autologous tumor.

NKG2D-CAR T cells or mock-treated autologous T cells were cultured at a 1:1 ratio with autologous patient PBMCs containing AML blasts, patient bone marrow aspirate involved by MM, ligand-negative cell lines (P815), or healthy allogeneic donor PBMCs. IFNγ in the supernatants was measured by ELISA (**p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001, ****p≤0.0001). T cells were incubated with an NKG2D-blocking monoclonal antibody or isotype control antibody prior to addition of target cells as indicated.

Discussion

Given the potential to target any of the eight NKG2D ligands found in various hematologic and solid malignancies, the efficacy in murine models (16–19,22), and the feasibility of manufacturing in preclinical studies, we embarked on this first-in-human trial to assess the safety and feasibility of NKG2D-CAR T cells in subjects with AML/MDS and MM. We demonstrated safety without identifying an MTD at cell doses ranging 1×106 to 3×107, when administered as a single infusion without prior lymphodepleting therapy and showed feasibility of manufacturing and administration without cryopreservation. We did not observe a robust efficacy signal in this initial phase 1 study. However, the NKG2D-CAR approach is still in early stages of clinical development and has several unique features and strengths: unlike antigens which are lineage-restricted to a subset of cancers, NKG2D-ligands are surface-expressed in more than 15 different malignancies, including colon, breast, and lung cancer, AML, MM, Ewing’s sarcoma, and neuroblastoma (11). Thus, if clinical efficacy can be achieved with a reasonable safety profile, NKG2D-CAR therapy would have an impact across many malignancies with significant medical need. Reactivity against eight, often concurrently expressed, ligands might counteract tumor evasion via clonal selection, mutations, and alternative splicing (38).

Given minimal surface expression of NKG2D ligands in normal tissues, long-term toxicities, such as B-cell aplasia (39) or myeloablation, seen with other CAR strategies targeting AML are not expected (40), and no grade ≥3 toxicities or autoimmune events related to NKG2D-CAR therapy were observed in this study. However, the inducible nature of NKG2D ligands raises concern for potential “on-target, off-tumor” toxicity and a positive feedback loop mediated by NKG2D-CAR T cells in the setting of systemic inflammation. Toxicity resembling clinical CRS at high cell doses was observed and exacerbated by cyclophosphamide in syngeneic mouse models (23,24). Therefore, lymphodepleting chemotherapy has been omitted pending a first-in-human safety experience, which is provided by this study. However, we evaluated pre-infusion ALC as a surrogate for the degree of preexisting “lymphodepletion”, and all patients with detectable NKG2D-CAR T cells had an ALC ≤0.59K/μL at infusion. Additional studies are warranted to assess the impact of lymphodepletion strategies on NKG2D ligand surface expression on healthy tissues and incorporation into future studies. NKG2D-CAR T cells were detectable in four patients and did not mediate any clinically relevant toxicity, specifically, no gastrointestinal autoimmune toxicity despite concerns for MICA/B expression on intestinal epithelial cells (41,42). Several patients developed systemic infections after infusion, which did not trigger any NKG2D-CAR T-cell expansion or toxicity. Although dose escalation started low, the final cohort of 3×107 cells approached doses at which toxicity and efficacy have been observed in CD19-directed CAR trials (0.5–1×106/kg) (4,43). Two patients in the highest dose cohort experienced a self-resolving skin rash within 1–3 months after infusion, one of which was deemed probably related to CAR T cells, although a skin biopsy was non-diagnostic.

Feasibility of manufacturing and infusion of NKG2D-CAR T cells from patients with AML or MM without cryopreservation was consistently demonstrated, including with cells derived from whole blood draws. Patient blasts and CD138+CD38+ plasma cells were efficiently eliminated during manufacturing. In a single instance, CD19+ B cells persisted and were transduced, similar to a reported phenomenon of leukemic B-cell transduction with a CAR (44). This did not result in clinical sequelae but raises consideration of a T-cell selection step during manufacturing.

Although the study met its primary endpoints, objective clinical efficacy was not demonstrated. However, one patient at the highest dose had blood count improvements and clinical stability without additional therapy for months, and several patients experienced unexpected disease stability on subsequent therapies. Our correlative studies interrogated several aspects amenable to optimization in future trials. In most patients, significant NKG2D-CAR T-cell expansion and persistence were not observed. This is consistent with murine models, where repeat infusions are required for complete tumor eradication (15). Owing to the conserved nature of NKG2D, NKG2D-CAR T cells are not immunogenic. Therefore, multiple infusions and higher cell doses commensurate with other CAR trials are now being explored (NCT 03018405) (45).

Although no costimulatory domain was incorporated in the CAR construct, the use of full-length NKG2D endowed the NKG2D-CAR with a costimulatory signal via endogenously expressed Dap10, which is required for NKG2D surface expression. Although Dap10 was not rate-limiting to NKG2D-CAR expression, its contribution to CAR T-cell efficacy has not been established and inclusion of additional costimulatory moieties, such as 4–1BB or CD28, might significantly enhance NKG2D-CAR T-cell kinetics and efficacy. Our current manufacturing method yielded predominantly a Tem profile, characteristic of cytotoxic effector function, but limited capacity to self-renew and expand in vivo. Modifications to induce differentiation towards a Tcm/T-memory stem cell (Tscm) profile (46), inclusion of 4–1BB to promote outgrowth of CD8+ Tcm subsets and CAR expansion via distinct metabolic pathways (47), or controlling the CD4/CD8 ratio may enhance future efficacy. Inclusion of a suicide mechanism and extracellular marker to directly identify NKG2D-CAR T cells in PB and tissues could further be beneficial in subsequent trials.

Antigen exposure is an additional factor for CAR T-cell expansion, and high disease burden is predictive of exponential expansion and associated CRS (39,48). The reported NKG2D ligand expression in AML varies in the literature (14,49–53). We found that expression on AML blasts and evaluable myeloma cells in our enrolled patients was low relative to CD19 expression in ALL. This may critically impact expansion, particularly because NKG2D-CAR T cells lack an alternative antigen source from non-malignant cells. NKG2D ligand cleavage, a known process of immune evasion, may have impacted surface ligand expression because all patients had detectable plasma concentrations of either soluble MICA, MICB, or both. In contrast, soluble ligands are unlikely to have impaired NKG2D-CAR T-cell function, given that in vitro NKG2D-CAR–mediated cytotoxicity was not inhibited by comparable concentrations of soluble MICA (20). Although additional strategies are required to promote NKG2D-CAR T-cell expansion in vivo, our in vitro studies evaluating the NKG2D-CAR T-cell product in coculture with autologous tumor cells demonstrated that ligand expression is sufficient to induce robust, tumor-specific, and NKG2D-mediated IFNγ. Increases in RANTES early after infusion are likely derived from the CAR T cells, suggesting an element of NKG2D ligand–specific activation (54). However, pharmacologic strategies to selectively enhance NKG2D ligand expression in malignant tissues and basing eligibility on NKG2D ligand expression may be warranted in future studies (52,55–59).

In summary, our findings represent a critical assessment of the safety and feasibility of NKG2D-CAR T-cell administration in humans. Although expansion and persistence of CAR T cells was limited, no safety concerns were raised with detectable NKG2D-CAR T cells in several subjects, despite clinical conditions of infection and systemic cell stress in which ligand upregulation in healthy tissues might have triggered toxicity. Our findings identify several mechanisms by which therapeutic efficacy might be achieved in subsequent studies and pave the way for further development of this approach.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank DartLab Immunoassay and Flow Cytometry Shared Resource at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth for their services with Luminex analysis.

Financial Support: This work was supported in part by NIH NHLBI 2R44HL09921, Celdara Medical LLC, Celyad SA and an Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation Centers of Excellence grant (S.H.B).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure Statement: S.H.B. and S.N. received salary support through an SBIR grant awarded to Celdara Medical. J.M., J.R. and A.S. are employed by Celdara Medical which has a material financial interest in NK receptor-based CAR intellectual property assigned to the Trustees of Dartmouth College. C.L.S. has patents and financial interests in NK receptor-based CAR therapies. C.L.S. is a scientific founder for Celdara Medical, a consultant, and has received research support from Celdara Medical. These conflicts are managed under the policies of Dartmouth College. D.E.G. and F.F.L. are employees of Celyad SA, the clinical trial sponsor. G.D. is currently an employee of Novartis which has material financial interests in other CAR T cell therapies. The other authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kochenderfer JN, Somerville RPT, Lu T, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Feldman SA, et al. Long-Duration Complete Remissions of Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma after Anti-CD19 Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy 2017;25(10):2245–53 doi 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maude SL, Laetsch TW, Buechner J, Rives S, Boyer M, Bittencourt H, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in Children and Young Adults with B-Cell Lymphoblastic Leukemia. The New England journal of medicine 2018;378(5):439–48 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1709866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park JH, Riviere I, Gonen M, Wang X, Senechal B, Curran KJ, et al. Long-Term Follow-up of CD19 CAR Therapy in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. The New England journal of medicine 2018;378(5):449–59 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1709919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gardner RA, Finney O, Annesley C, Brakke H, Summers C, Leger K, et al. Intent-to-treat leukemia remission by CD19 CAR T cells of defined formulation and dose in children and young adults. Blood 2017;129(25):3322–31 doi 10.1182/blood-2017-02-769208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neelapu SS, Locke FL, Bartlett NL, Lekakis LJ, Miklos DB, Jacobson CA, et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel CAR T-Cell Therapy in Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma. The New England journal of medicine 2017;377(26):2531–44 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1707447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turtle CJ, Hanafi LA, Berger C, Hudecek M, Pender B, Robinson E, et al. Immunotherapy of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma with a defined ratio of CD8+ and CD4+ CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells. Science translational medicine 2016;8(355):355ra116 doi 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf8621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lanier LL. NKG2D Receptor and Its Ligands in Host Defense. Cancer immunology research 2015;3(6):575–82 doi 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garrity D, Call ME, Feng J, Wucherpfennig KW. The activating NKG2D receptor assembles in the membrane with two signaling dimers into a hexameric structure. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2005;102(21):7641–6 doi 10.1073/pnas.0502439102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rebmann V, Schutt P, Brandhorst D, Opalka B, Moritz T, Nowrousian MR, et al. Soluble MICA as an independent prognostic factor for the overall survival and progression-free survival of multiple myeloma patients. Clin Immunol 2007;123(1):114–20 doi 10.1016/j.clim.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jinushi M, Vanneman M, Munshi NC, Tai YT, Prabhala RH, Ritz J, et al. MHC class I chain-related protein A antibodies and shedding are associated with the progression of multiple myeloma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105(4):1285–90 doi 10.1073/pnas.0711293105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spear P, Wu MR, Sentman ML, Sentman CL. NKG2D ligands as therapeutic targets. Cancer immunity 2013;13:8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.von Strandmann EP, Hansen HP, Reiners KS, Schnell R, Borchmann P, Merkert S, et al. A novel bispecific protein (ULBP2-BB4) targeting the NKG2D receptor on natural killer (NK) cells and CD138 activates NK cells and has potent antitumor activity against human multiple myeloma in vitro and in vivo. Blood 2006;107(5):1955–62 doi 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Groh V, Rhinehart R, Secrist H, Bauer S, Grabstein KH, Spies T. Broad tumor-associated expression and recognition by tumor-derived gamma delta T cells of MICA and MICB. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1999;96(12):6879–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hilpert J, Grosse-Hovest L, Grunebach F, Buechele C, Nuebling T, Raum T, et al. Comprehensive analysis of NKG2D ligand expression and release in leukemia: implications for NKG2D-mediated NK cell responses. J Immunol 2012;189(3):1360–71 doi 10.4049/jimmunol.1200796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barber A, Meehan KR, Sentman CL. Treatment of multiple myeloma with adoptively transferred chimeric NKG2D receptor-expressing T cells. Gene therapy 2011;18(5):509–16 doi 10.1038/gt.2010.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barber A, Zhang T, Megli CJ, Wu J, Meehan KR, Sentman CL. Chimeric NKG2D receptor-expressing T cells as an immunotherapy for multiple myeloma. Experimental hematology 2008;36(10):1318–28 doi 10.1016/j.exphem.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barber A, Zhang T, Sentman CL. Immunotherapy with chimeric NKG2D receptors leads to long-term tumor-free survival and development of host antitumor immunity in murine ovarian cancer. J Immunol 2008;180(1):72–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang T, Barber A, Sentman CL. Chimeric NKG2D modified T cells inhibit systemic T-cell lymphoma growth in a manner involving multiple cytokines and cytotoxic pathways. Cancer research 2007;67(22):11029–36 doi 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barber A, Zhang T, DeMars LR, Conejo-Garcia J, Roby KF, Sentman CL. Chimeric NKG2D receptor-bearing T cells as immunotherapy for ovarian cancer. Cancer research 2007;67(10):5003–8 doi 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang T, Barber A, Sentman CL. Generation of antitumor responses by genetic modification of primary human T cells with a chimeric NKG2D receptor. Cancer research 2006;66(11):5927–33 doi 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang T, Lemoi BA, Sentman CL. Chimeric NK-receptor-bearing T cells mediate antitumor immunotherapy. Blood 2005;106(5):1544–51 doi 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spear P, Barber A, Rynda-Apple A, Sentman CL. NKG2D CAR T-cell therapy inhibits the growth of NKG2D ligand heterogeneous tumors. Immunology and cell biology 2013;91(6):435–40 doi 10.1038/icb.2013.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sentman ML, Murad JM, Cook WJ, Wu MR, Reder J, Baumeister SH, et al. Mechanisms of Acute Toxicity in NKG2D Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell-Treated Mice. J Immunol 2016;197(12):4674–85 doi 10.4049/jimmunol.1600769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.VanSeggelen H, Hammill JA, Dvorkin-Gheva A, Tantalo DG, Kwiecien JM, Denisova GF, et al. T Cells Engineered With Chimeric Antigen Receptors Targeting NKG2D Ligands Display Lethal Toxicity in Mice. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy 2015;23(10):1600–10 doi 10.1038/mt.2015.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheson BD, Bennett JM, Kopecky KJ, Buchner T, Willman CL, Estey EH, et al. Revised recommendations of the International Working Group for Diagnosis, Standardization of Response Criteria, Treatment Outcomes, and Reporting Standards for Therapeutic Trials in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2003;21(24):4642–9 doi 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheson BD, Greenberg PL, Bennett JM, Lowenberg B, Wijermans PW, Nimer SD, et al. Clinical application and proposal for modification of the International Working Group (IWG) response criteria in myelodysplasia. Blood 2006;108(2):419–25 doi 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Durie BG, Harousseau JL, Miguel JS, Blade J, Barlogie B, Anderson K, et al. International uniform response criteria for multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2006;20(9):1467–73 doi 10.1038/sj.leu.2404284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rajkumar SV, Harousseau JL, Durie B, Anderson KC, Dimopoulos M, Kyle R, et al. Consensus recommendations for the uniform reporting of clinical trials: report of the International Myeloma Workshop Consensus Panel 1. Blood 2011;117(18):4691–5 doi 10.1182/blood-2010-10-299487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dohner H, Estey E, Grimwade D, Amadori S, Appelbaum FR, Buchner T, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood 2017;129(4):424–47 doi 10.1182/blood-2016-08-733196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang T, Barber A, Sentman CL. Generation of antitumor responses by genetic modification of primary human T cells with a chimeric NKG2D receptor. Cancer research 2006;66(11):5927–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riviere I, Brose K, Mulligan RC. Effects of retroviral vector design on expression of human adenosine deaminase in murine bone marrow transplant recipients engrafted with genetically modified cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1995;92(15):6733–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murad JM, Baumeister SH, Werner L, Daley H, Trebeden-Negre H, Reder J, et al. Manufacturing development and clinical production of NKG2D chimeric antigen receptor-expressing T cells for autologous adoptive cell therapy. Cytotherapy 2018;20(7):952–63 doi 10.1016/j.jcyt.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burns MJ, Nixon GJ, Foy CA, Harris N. Standardisation of data from real-time quantitative PCR methods - evaluation of outliers and comparison of calibration curves. BMC biotechnology 2005;5:31 doi 10.1186/1472-6750-5-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen J, Reeves L, Cornetta K. Safety testing for replication-competent retrovirus associated with gibbon ape leukemia virus-pseudotyped retroviral vectors. Human gene therapy 2001;12(1):61–70 doi 10.1089/104303401450979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mehta J, Singhal S. Hyperviscosity syndrome in plasma cell dyscrasias. Seminars in thrombosis and hemostasis 2003;29(5):467–71 doi 10.1055/s-2003-44554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sobol U, Stiff P. Neurologic aspects of plasma cell disorders. Handbook of clinical neurology 2014;120:1083–99 doi 10.1016/B978-0-7020-4087-0.00073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borchers MT, Harris NL, Wesselkamper SC, Vitucci M, Cosman D. NKG2D ligands are expressed on stressed human airway epithelial cells. American journal of physiology Lung cellular and molecular physiology 2006;291(2):L222–31 doi 10.1152/ajplung.00327.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sotillo E, Barrett DM, Black KL, Bagashev A, Oldridge D, Wu G, et al. Convergence of Acquired Mutations and Alternative Splicing of CD19 Enables Resistance to CART-19 Immunotherapy. Cancer discovery 2015;5(12):1282–95 doi 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maude SL, Shpall EJ, Grupp SA. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for ALL. Hematology American Society of Hematology Education Program 2014;2014(1):559–64 doi 10.1182/asheducation-2014.1.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cummins KD, Gill S. Anti-CD123 chimeric antigen receptor T-cells (CART): an evolving treatment strategy for hematological malignancies, and a potential ace-in-the-hole against antigen-negative relapse. Leukemia & lymphoma 2017:1–15 doi 10.1080/10428194.2017.1375107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perera L, Shao L, Patel A, Evans K, Meresse B, Blumberg R, et al. Expression of nonclassical class I molecules by intestinal epithelial cells. Inflammatory bowel diseases 2007;13(3):298–307 doi 10.1002/ibd.20026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hansen CH, Holm TL, Krych L, Andresen L, Nielsen DS, Rune I, et al. Gut microbiota regulates NKG2D ligand expression on intestinal epithelial cells. European journal of immunology 2013;43(2):447–57 doi 10.1002/eji.201242462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brudno JN, Somerville RP, Shi V, Rose JJ, Halverson DC, Fowler DH, et al. Allogeneic T Cells That Express an Anti-CD19 Chimeric Antigen Receptor Induce Remissions of B-Cell Malignancies That Progress After Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem-Cell Transplantation Without Causing Graft-Versus-Host Disease. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2016;34(10):1112–21 doi 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.5929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lacey SXJ, Ruella M., Barrett DM; Kulikovskaya I; Ambrose DE; Patel PR; Reich T; Scholler J, Nazimuddin F; Fraietta JA; Maude SL, Gill SI; Levine BL; Nobles CL; Bushman FD; Orlando E; Grupp SA; June CH; Melenhorst JJ Cars in Leukemia: Relapse with Antigen-Negative Leukemia Originating from a single B Cell Expressing the Leukemia-Targeting CAR. Blood 2016;128(22):281. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sallman DA, Brayer J, Sagatys EM, Lonez C, Breman E, Agaugue S, et al. NKG2D-based chimeric antigen receptor therapy induced remission in a relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia patient. Haematologica 2018. doi 10.3324/haematol.2017.186742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gattinoni L, Restifo NP. Moving T memory stem cells to the clinic. Blood 2013;121(4):567–8 doi 10.1182/blood-2012-11-468660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kawalekar OU, OC RS, Fraietta JA, Guo L, McGettigan SE, Posey AD Jr., et al. Distinct Signaling of Coreceptors Regulates Specific Metabolism Pathways and Impacts Memory Development in CAR T Cells. Immunity 2016;44(3):712 doi 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maude SL, Frey N, Shaw PA, Aplenc R, Barrett DM, Bunin NJ, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. The New England journal of medicine 2014;371(16):1507–17 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1407222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mastaglio S, Wong E, Perera T, Ripley J, Blombery P, Smyth MJ, et al. Natural killer receptor ligand expression on acute myeloid leukemia impacts survival and relapse after chemotherapy. Blood advances 2018;2(4):335–46 doi 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017015230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sanchez-Correa B, Morgado S, Gayoso I, Bergua JM, Casado JG, Arcos MJ, et al. Human NK cells in acute myeloid leukaemia patients: analysis of NK cell-activating receptors and their ligands. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy : CII 2011;60(8):1195–205 doi 10.1007/s00262-011-1050-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pende D, Spaggiari GM, Marcenaro S, Martini S, Rivera P, Capobianco A, et al. Analysis of the receptor-ligand interactions in the natural killer-mediated lysis of freshly isolated myeloid or lymphoblastic leukemias: evidence for the involvement of the Poliovirus receptor (CD155) and Nectin-2 (CD112). Blood 2005;105(5):2066–73 doi 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Diermayr S, Himmelreich H, Durovic B, Mathys-Schneeberger A, Siegler U, Langenkamp U, et al. NKG2D ligand expression in AML increases in response to HDAC inhibitor valproic acid and contributes to allorecognition by NK-cell lines with single KIR-HLA class I specificities. Blood 2008;111(3):1428–36 doi 10.1182/blood-2007-07-101311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Salih HR, Antropius H, Gieseke F, Lutz SZ, Kanz L, Rammensee HG, et al. Functional expression and release of ligands for the activating immunoreceptor NKG2D in leukemia. Blood 2003;102(4):1389–96 doi 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Levy JA. The unexpected pleiotropic activities of RANTES. J Immunol 2009;182(7):3945–6 doi 10.4049/jimmunol.0990015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Poggi A, Catellani S, Garuti A, Pierri I, Gobbi M, Zocchi MR. Effective in vivo induction of NKG2D ligands in acute myeloid leukaemias by all-trans-retinoic acid or sodium valproate. Leukemia 2009;23(4):641–8 doi 10.1038/leu.2008.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Skov S, Pedersen MT, Andresen L, Straten PT, Woetmann A, Odum N. Cancer cells become susceptible to natural killer cell killing after exposure to histone deacetylase inhibitors due to glycogen synthase kinase-3-dependent expression of MHC class I-related chain A and B. Cancer research 2005;65(23):11136–45 doi 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Soriani A, Zingoni A, Cerboni C, Iannitto ML, Ricciardi MR, Di Gialleonardo V, et al. ATM-ATR-dependent up-regulation of DNAM-1 and NKG2D ligands on multiple myeloma cells by therapeutic agents results in enhanced NK-cell susceptibility and is associated with a senescent phenotype. Blood 2009;113(15):3503–11 doi 10.1182/blood-2008-08-173914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rohner A, Langenkamp U, Siegler U, Kalberer CP, Wodnar-Filipowicz A. Differentiation-promoting drugs up-regulate NKG2D ligand expression and enhance the susceptibility of acute myeloid leukemia cells to natural killer cell-mediated lysis. Leukemia research 2007;31(10):1393–402 doi 10.1016/j.leukres.2007.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abruzzese MP, Bilotta MT, Fionda C, Zingoni A, Soriani A, Vulpis E, et al. Inhibition of bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) proteins increases NKG2D ligand MICA expression and sensitivity to NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity in multiple myeloma cells: role of cMYC-IRF4-miR-125b interplay. Journal of hematology & oncology 2016;9(1):134 doi 10.1186/s13045-016-0362-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.