HSV-1-induced eye disease is a major public health problem. Eye disease is associated closely with immune responses to the virus and is exacerbated by delayed clearance of the primary infection. The immune system relies on antigen-presenting cells of the innate immune system to activate the T cell response. We found that HSV-1 utilizes a robust and finely targeted mechanism of local immune evasion. It downregulates the expression of the costimulatory molecule CD80 but not CD86 on resident dendritic cells irrespective of the presence of anti-HSV-1 antibodies. The effect is mediated by direct binding of HSV-1 ICP22, the product of an immediate early gene of HSV-1, to the promoter of CD80. This immune evasion mechanism dampens the host immune response and, thus, reduces eye disease in ocularly infected mice. Therefore, ICP22 may be a novel inhibitor of CD80 that could be used to modulate the immune response.

KEYWORDS: antigen-presenting cells, cornea, immediate early genes, corneal scarring, virus replication, immune suppression, eye disease

ABSTRACT

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) has the ability to delay its clearance from the eye during ocular infection. Here, we show that ocular infection of mice with HSV-1 suppressed expression of the costimulatory molecule CD80 but not CD86 in the cornea. The presence of neutralizing anti-HSV-1 antibodies did not alleviate this suppression. At the cellular level, HSV-1 consistently downregulated the expression of CD80 by dendritic cells (DCs) but not by other antigen-presenting cells. Furthermore, flow cytometric analysis of HSV-1-infected corneal cells during a 7-day period reduced CD80 expression in DCs but not in B cells, macrophages, or monocytes. This suppression was associated with the presence of virus. Similar results were obtained using infected or transfected spleen cells or bone marrow-derived DCs. A combination of roscovitine treatment, transfection with immediate early genes (IE), and infection with a recombinant HSV-1 lacking the ICP22 gene shows the importance of ICP22 in downregulation of the CD80 promoter but not the CD86 promoter in vitro and in vivo. At the mechanistic level, we show that the HSV-1 immediate early gene ICP22 binds the CD80 promoter and that this interaction is required for HSV-1-mediated suppression of CD80 expression. Conversely, forced expression of CD80 by ocular infection of mice with a recombinant HSV-1 exacerbated corneal scarring in infected mice. Taken together, these studies identify ICP22-mediated suppression of CD80 expression in dendritic cells as central to delayed clearance of the virus and limitation of the cytopathological response to primary infection in the eye.

IMPORTANCE HSV-1-induced eye disease is a major public health problem. Eye disease is associated closely with immune responses to the virus and is exacerbated by delayed clearance of the primary infection. The immune system relies on antigen-presenting cells of the innate immune system to activate the T cell response. We found that HSV-1 utilizes a robust and finely targeted mechanism of local immune evasion. It downregulates the expression of the costimulatory molecule CD80 but not CD86 on resident dendritic cells irrespective of the presence of anti-HSV-1 antibodies. The effect is mediated by direct binding of HSV-1 ICP22, the product of an immediate early gene of HSV-1, to the promoter of CD80. This immune evasion mechanism dampens the host immune response and, thus, reduces eye disease in ocularly infected mice. Therefore, ICP22 may be a novel inhibitor of CD80 that could be used to modulate the immune response.

INTRODUCTION

Herpes stromal keratitis (HSK), is the leading cause of blindness in developed nations and requires medical treatment and sometimes corneal transplants (1–5). It is estimated that the recurrence rate in infected individuals steadily increases over time (6). Moreover, most adults display antibodies to herpes simplex virus (HSV), with HSV-1 accounting for greater than 90% of HSV-1 eye disease and about 25% of ocularly infected adults presenting clinical symptoms (1–5, 7). After ocular exposure, HSV-1 replicates in the eye, and at around days 6 to 7 postinfection (p.i.), it gets cleared from the eye, which leads to herpes latency in the trigeminal ganglia (TG) of the infected individual (8, 9). In some cases, when the virus can occasionally reactivate by retrograde transport to the eye, it can cause recurrent infection, which can lead to blindness (3, 4). Indeed, the scarring induced by HSV-1 after reactivation from latency is a predominant cause of corneal scarring (CS). Due to the preexisting immunity, there is a higher likelihood of CS following recurrent, instead of primary, infection (1, 3, 4).

The possible role of CD4+ T cells as an orchestrator of HSV-1 eye disease is in stark contrast to the activity of CD8+ T cells, which can be protective or detrimental to the host (10–12). However, other reports using a similar murine model state the opposite conclusions with CD4+ T cells being protective and CD8+ T cells being detrimental after HSV-1 ocular infection (13–15). Based on reports using knockout mice and depletion studies, evidence supports the observation that CD4+ and CD8+ T cells protect against HSV-1 eye disease in ocularly infected mice (16). These cells are activated by CD80 and CD86, which are costimulatory molecules that play key roles in T cell activation and proliferation, including induction of tolerance (17). The binding of CD80 or CD86 to binding partners CTLA-4 or CD28 (17) and the binding of CD80 to programmed death-1 ligand (PD-L1) (18, 19) are necessary for T cell activation and tolerance. Both CD86 and CD80 costimulatory molecules are expressed by a variety of antigen-presenting cells (APCs), which include macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), and B cells, as well as T cells (20–23); however, their expression levels are regulated individually, and there are temporal specificities in their protein expression levels after stimulation (20, 21, 24). In knockout studies, CD86 is more important for T cell activation, in contrast to CD80, which helps to maintain these T cell responses (25). Taken together, both of their functions may be critical in both the induction of effector T cell activation and their proliferation (26).

The current studies were designed to investigate the role of CD80 and CD86 costimulation in a murine model of ocular HSV-1 infection. We show for the first time (i) that ocular infection of mice with HSV-1 suppresses expression of CD80 but not CD86 on dendritic cells, (ii) that suppression requires the local presence of infectious virus but is unaffected by anti-HSV-1 antibodies, (iii) that the suppression is mediated by HSV-1 ICP22, which binds to the CD80 promoter, and (iv) that recombinant HSV-1 overexpressing murine CD80 exacerbates corneal scarring in mice.

RESULTS

Full-length CD80 and its splice variant, but not CD86, are downregulated in the corneas of HSV-1-infected mice.

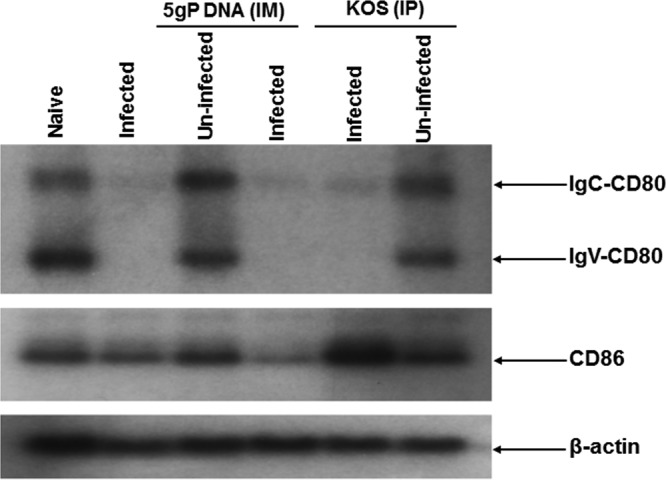

To determine if ocular infection with HSV-1 affects transcription of CD80 or CD86 in the cornea, we ocularly infected BALB/c mice with HSV-1 strain McKrae. On day 5 p.i., total RNA was isolated from the corneas, and cDNA synthesis and Southern analysis were carried out using the CD80 or CD86 gene as a probe (Fig. 1). CD80 can be expressed as the full-length form (IgC-CD80), which is 307 amino acids (aa) long and contains four exons (I, II, III, and IV), and as a 203-aa variant (IgV-CD80) in which exon III of IgC-CD80 is spliced out. IgV-CD80 and IgC-CD80 transcripts were detected in the corneas from naive, uninfected mice, and both CD80 transcripts were significantly downregulated in naive mice that were infected with HSV-1 strain McKrae (Fig. 1, CD80). In contrast, HSV-1 infection had no effect on the levels of CD86 transcripts (Fig. 1, CD86).

FIG 1.

Southern analyses. BALB/c mice were inoculated with DNA of five glycoproteins (gB, gC, gD, gE, and gI [5gP]) or avirulent HSV-1 strain KOS or mock treated as described in Materials and Methods. Inoculated or mock-treated mice were ocularly infected with 2 × 105 PFU/eye of virulent HSV-1 strain McKrae virus. As a control, some of the inoculated or mock-treated mice were not ocularly infected. Corneas from 3 mice per treatment were isolated at 5 days p.i. and combined, and total RNA was extracted. cDNA synthesis was performed on the total extracted RNA, and the cDNAs were separated using a 0.9% agarose gel, transferred to Zeta paper, rinsed in 2 × SSC (1 × SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) for 5 min, and cross-linked to the membrane by UV light. DNA-DNA hybridization was carried out using 32P-labeled CD80, CD86, or the β-actin gene (as a control) as we described previously (85).

To investigate the effects of neutralizing anti-HSV-1 antibodies on the HSV-1-induced downregulation of CD80, we inoculated BALB/c mice with a DNA cocktail containing equal amounts of “naked” DNA corresponding to the HSV-1 gB, gC, gD, gE, and gI genes or KOS, which is an avirulent strain of HSV-1, prior to ocular infection with HSV-1 strain McKrae. We have demonstrated previously that these protocols stimulate the production of circulating neutralizing anti-HSV-1 antibodies and that these antibodies are present in the corneas of the inoculated mice (27, 28). Both transcripts were significantly downregulated in infected immunized mice compared to levels in their uninfected immunized or mock-treated and uninfected counterparts (Fig. 1, CD80). HSV-1 infection had no effect on the levels of CD86 transcripts in the immunized mice (Fig. 1, CD86).

The levels of β-actin transcripts were the same among the groups of mice used in these experiments (Fig. 1, β-actin). Taken together, these results suggest that ocular infection with HSV-1 downregulates IgV-CD80 and IgC-CD80 transcripts in the cornea and that this downregulation is not affected by the presence of neutralizing antibodies to HSV-1.

HSV-1 ocular infection downregulates expression of CD80 but not CD86 in splenocytes.

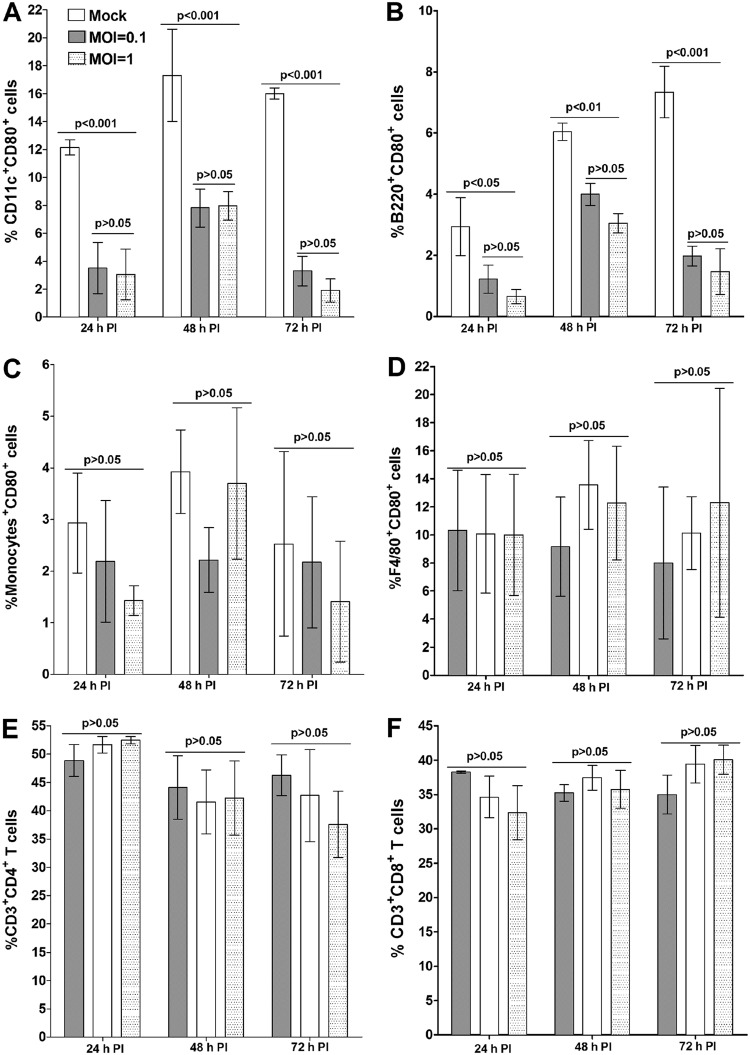

As CD80 and CD86 are found in several different types of APCs, we also tested the effects of infection with HSV-1 on the levels of CD80 and CD86 protein expression in subsets of splenocytes (Fig. 2). Splenocytes were isolated from C57BL/6 mice, infected with HSV-1 strain McKrae in vitro for 24, 48, and 72 h, and then immunostained. Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis was performed by gating for CD11c+ CD80+ cells, CD11b+ CD80+ cells, B220+ CD80+ cells, and F4/80+ CD80+ cells. CD80 expression by DCs (Fig. 2A) and B cells (Fig. 2B) was significantly lower than that in mock-infected cells at both levels of infection and at all three time points. There was no significant difference in CD80 expression levels between infected and uninfected monocytes (Fig. 2C) and macrophages (Fig. 2D). Proportions of CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2E) or CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2F) were not different between infected and mock-infected groups. Taken together, these results show that DCs and B cells were the only cell types showing a reduction in CD80 expression after infection. We also looked at the effect of infection on expression of CD86 and of CD80 plus CD86 in infected splenocytes (data not shown). No suppression of CD86 was detected in infected DCs, B cells, monocytes, or macrophages (data not shown). Finally, no differences were detected in expression levels of CD80 plus CD86 by DCs, monocytes, B cells, or macrophages (data not shown). Overall, these results suggest that expression of CD80, but not of CD86, is suppressed by HSV-1 infection and that the suppression of CD80 is limited to specific types of APCs, i.e., DCs and B cells, in the spleen.

FIG 2.

Suppression of CD80 expression by DCs in HSV-1 infected splenocytes in vitro. Cultured splenocytes from naive mice were infected with 0.1 or 1 PFU/cell of HSV-1 strain McKrae or mock infected. Infected or mock-infected cells were collected at 24, 48, and 72 h p.i. for FACS analysis as described in Materials and Methods. Cells were stained with anti-CD11c, anti-CD11b, anti-B220, anti-F4/80, anti-CD3, anti-CD4, anti-CD8, and anti-CD80 antibodies. FACS analysis was performed by gating for CD11c+ CD80+ cells, CD11b+ CD80+ cells, B220+ CD80+ cells, F4/80+ CD80+ cells, CD3+ CD4+ CD80+ cells, and CD3+ CD8+ CD80+ cells, as indicated. Data are presented as means ± SEM from three independent studies and with three replications per each experiment (n = 9). Statistical analysis was done using two-way ANOVA to test for P values.

Downregulation of CD80 in DCs in the corneas of mice ocularly infected with HSV-1.

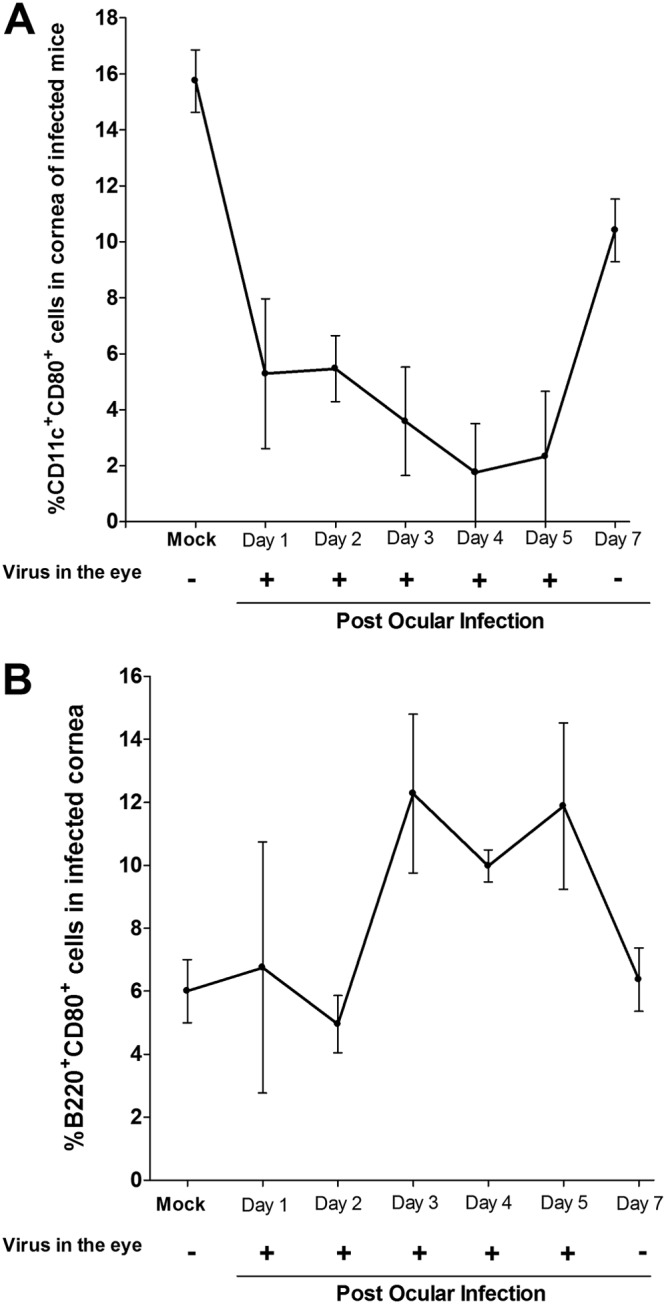

To determine the effects of HSV-1 infection on DCs and B cells in the cornea, we ocularly infected C57BL/6 mice with HSV-1 strain McKrae. The presence of virus in the eyes of the infected mice was determined using a standard plaque assay. Corneas were isolated on days 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 7 p.i., and single-cell suspensions were prepared that were stained with anti-CD11c, anti-B220, anti-CD11b, anti-CD80, and anti-CD86 monoclonal antibodies. FACS analysis (Fig. 3) revealed that CD80 expression in DCs was significantly lower in the HSV-1-infected mice than in the mock-infected mice on day 1 p.i. and remained significantly lower up to day 5 p.i. On day 7, however, there was a sharp increase in CD80 expression in the DCs (Fig. 3A). There was a direct correlation between CD80 expression by DCs with the presence of virus in the tears of infected mice (Fig. 3A). In contrast to suppression of expression of CD80 by DCs in infected splenocytes (Fig. 2A), the expression in B cells in the corneas of infected mice did not exhibit a decreasing trend; instead levels increased after day 3 and were not significantly different from the levels of expression by the B cells in the corneas of the mock-infected mice at day 7 p.i. (Fig. 3B). However, there was no direct correlation between expression of CD86 and of CD80 plus CD86 by DCs or of CD86 and of CD80 plus CD86 by B cells (data not shown). Overall, these results suggest that CD80 expression by DCs but not B cells in the corneas of infected mice was suppressed and that this suppression was dependent on the presence of virus in the eyes of ocularly infected mice.

FIG 3.

HSV-1 infection suppresses CD80 expression in cornea of infected mice. C57BL/6 mice were infected in both eyes with 2 × 105 PFU/eye of HSV-1 strain McKrae. Corneas from infected mice were isolated on days 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 7 p.i. Isolated corneas from each mouse were digested with collagenase and washed, and the cell suspension was stained with anti-CD11c, anti-B220, and anti-CD80 antibodies prior to flow cytometry analysis as described in Materials and Methods. Tear films were also collected on the indicated days, and virus titers were determined using standard plaque assays. Quantitation of the mean number of CD11c+ CD80+ cells or B220+ CD80+ cells ± SEM from three independent experiments with three replications per individual mouse corneas is shown (n = 9). The presence (+) or the absence (−) of virus in tear films of infected mice for each indicated time point is shown. Each point represents the mean ± SEM for 10 mice (20 eyes) per time point.

HSV-1 downregulates CD80 in BMDCs.

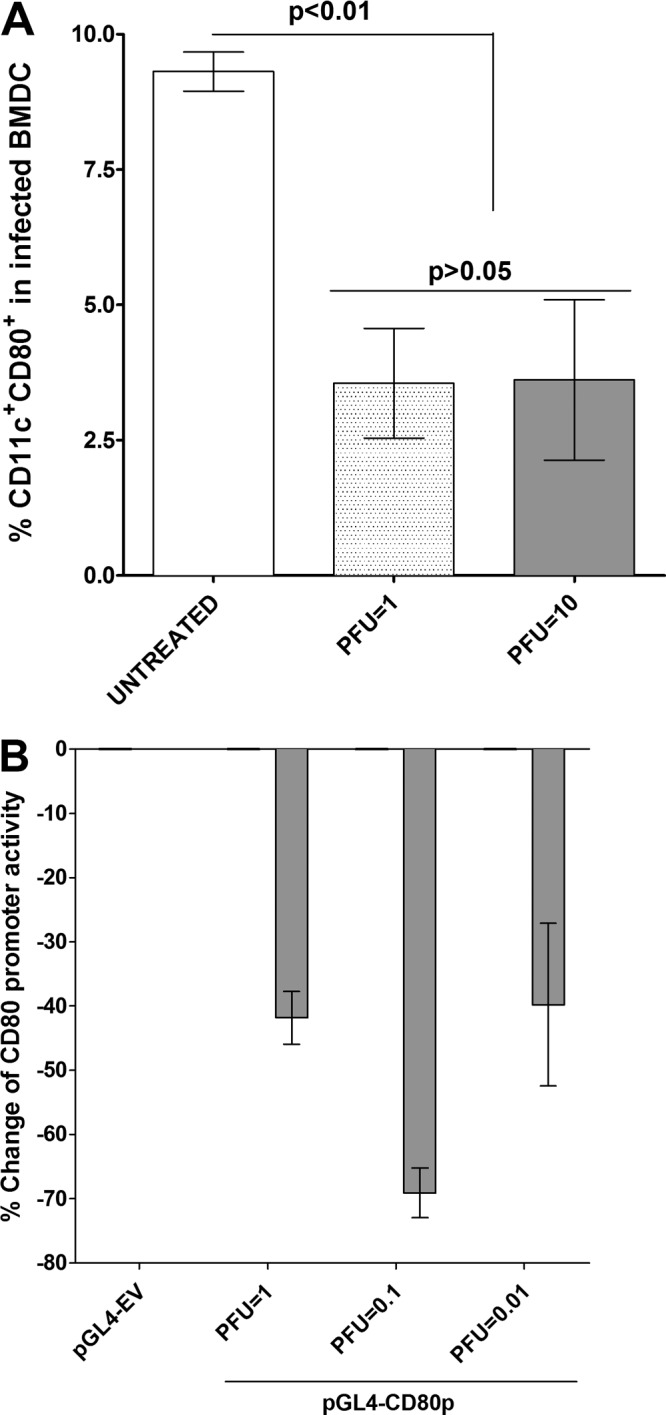

To further test HSV-1-induced suppression of CD80 in DCs, mouse bone marrow-derived DCs (BMDCs) were generated and infected with 1 or 10 PFU/cell of McKrae virus for 24 h. The cells were then stained with anti-CD11c, anti-CD80, and anti-CD86 antibodies. FACS analysis (Fig. 4A) revealed that the percentages of CD80+ CD11c+ cells were significantly lower in the HSV-1-infected cells than the untreated BMDCs (Fig. 4A) (P< 0.01). In contrast, we did not detect any significant differences in the percentages of CD11c+ CD86+ cells or CD11c+ CD80+ CD86+ cells between the infected and uninfected cultured BMDCs (data not shown).

FIG 4.

Suppression of CD80 in infected BMDCs. Subconfluent monolayers of DCs isolated from C57BL/6 mice were infected with 1 or 10 PFU/cell of HSV-1 strain McKrae for 24 h as described in Materials and Methods. In some experiments DCs were transfected with pGL4-CD80p or pGL4-EV and 72 h later infected with 1, 0.1, or 0.01 PFU/cell of McKrae virus for 24 h. Untreated DCs were used as a control for both groups. In the first group, infected DCs were stained with anti-CD11c and anti-CD80 antibodies, and percentages of CD11c+ CD80+ cells ± SEM from three independent experiments with three replications of each experiment are shown (n = 9). In the transfected and infected DCs, the changes in CD80 promoter activity were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Each point represents the mean ± SEM (n = 9) from three separate experiments. Statistical analyses were done using ANOVA to test for P values.

We next transfected BMDCs with pGL4-CD80p or pGL4-EV DNA for 48 h and infected the transfected BMDCs with 1, 0.1, and 0.01 PFU/cell of McKrae for 24 h. On analysis of luciferase promoter activity, we found that the CD80 promoter activity was reduced by 40%, 70%, and 38% at 1, 0.1, and 0.01 PFU/cell, respectively, compared with the level for pGL4-EV without infection (Fig. 4B). These results confirm our overall finding that HSV-1 suppresses CD80 expression by DCs at the transcriptional level.

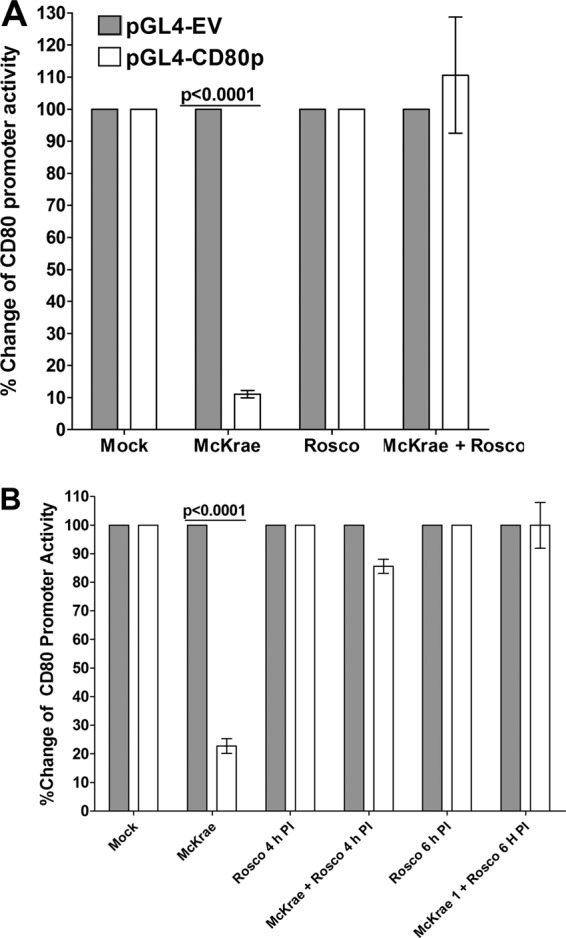

Immediate early HSV-1 genes are responsible for suppression of CD80.

During productive infection, more than 80 HSV-1 genes are expressed. These are subdivided into three major classes based on the kinetics of their expression: immediate early (IE), early (E), and late (L). These can be further subdivided into early-early, early-late, late-early, and late-late genes (29). Roscovitine blocks expression of IE and E genes (30, 31). We therefore transfected HEK 293 cells with either pGL4-EV or pGL4-CD80p and 48 h later infected them with 1 PFU/cell of McKrae virus in the presence or absence of roscovitine for 1 h. Roscovitine alone had no effect (Fig. 5A, Rosco). In the absence of roscovitine, HSV-1 suppressed CD80 promoter activity (Fig. 5A, McKrae). However, in the presence of roscovitine, the McKrae virus-mediated suppression of CD80 was blocked (Fig. 5A, McKrae + Rosco). We further tested if adding roscovitine as late as 4 or 6 h p.i. can prevent the reduction of CD80 promoter activity. HEK 293 cells were transfected as described in the legend of Fig. 5A with either pGL4-EV or pGL4-CD80p. After 48 h the transfected cells were infected with 1 PFU/cell of McKrae virus alone, roscovitine alone, or McKrae plus roscovitine for 4 or 6 h (Fig. 5B). Similar to the results presented in Fig. 5A, in the presence of both McKrae and roscovitine suppression of CD80 was blocked when roscovitine was added at 4 h p.i. (Fig. 5B, McKrae + Rosco 4 h PI) or 6 h p.i. (Fig. 5B, McKrae + Rosco 6 h PI). Collectively, these results suggest that the HSV-1 suppression of the CD80 promoter activity is associated with expression of the viral immediate early (IE) and/or early (E) genes.

FIG 5.

Effects of roscovitine treatment on CD80 promoter activity. HEK 293 cells were grown and transfected with pGL4-EV or pGL4-CD80p DNA as described in the legend of Fig. 4. Transfected cells were incubated with McKrae virus, roscovitine, or both, and CD80 promoter activity was determined 1 h after roscovitine treatment (A) as described in Materials and Methods. In some of the experiments, roscovitine treatment was carried out at 4 h and 6 h p.i. instead of at 0 h p.i. (B). Each point represents the mean ± SEM from three separate experiments (n = 9). Statistical analyses were done using ANOVA to test for P values.

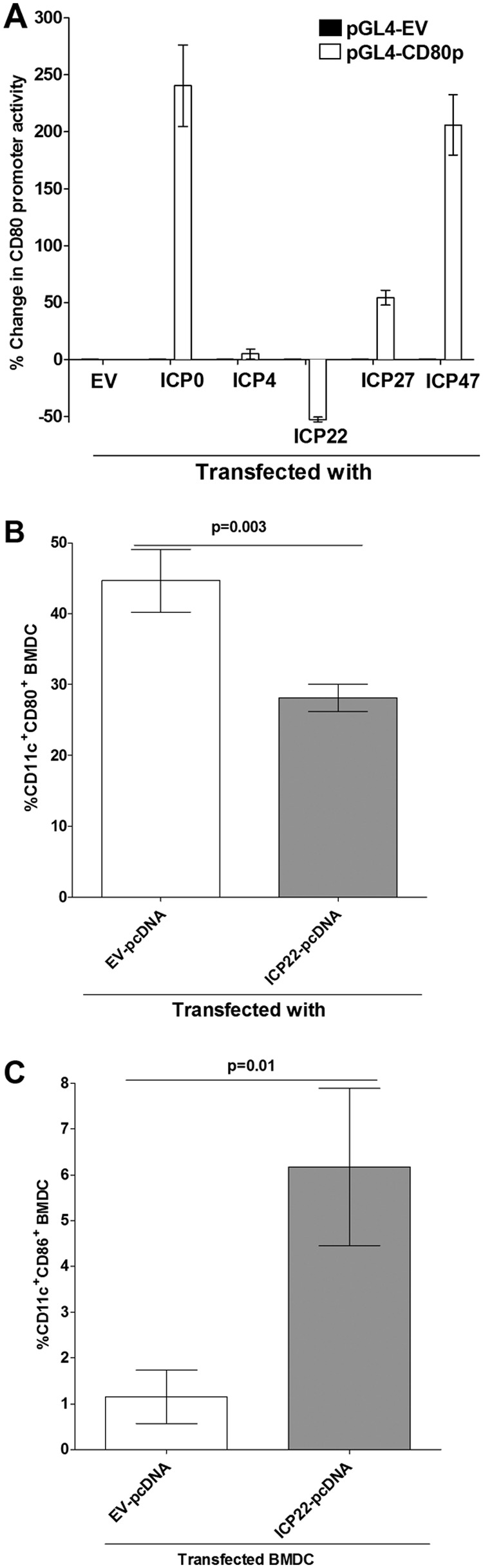

ICP22 suppresses CD80 promoter activity.

To identify which of the five HSV-1 immediate early genes contributes to the suppression of CD80 expression, we cloned the ICP0, ICP4, ICP22, ICP27, and ICP47 genes in a pcDNA3.1 backbone. We transfected the HEK 293 cells with each individual immediate early gene and pGL4-EV or pGL4-CD80p plasmid and used a dual-luciferase reporter (DLR) system to determine the CD80 promoter activity. Our results demonstrated that transfection with ICP4 had no effect on CD80 promoter activity (Fig. 6A, ICP4), whereas transfection with ICP0, ICP27, or ICP47 significantly increased CD80 activity compared to that with pGL4-EV treatment (Fig. 6A). In contrast, transfection with ICP22 reduced CD80 promoter activity by greater than 50% (Fig. 6A). These differences between the CD80 promoter activity in HSV-1-infected HEK 293 cells transfected with ICP22 and the activity in those transfected with the other four immediate early genes were statistically significant (Fig. 6A) (P < 0.001).

FIG 6.

Effects of immediate early genes on CD80 promoter activity. (A) Effect of IE genes on transfected HEK 293 cells. HEK 293 cells were transfected with either pGL4-EV or pGL4-CD80p DNA and 24 h later were individually transfected with ICP0, ICP4, ICP22, ICP27, or ICP47 DNA, and their effect on CD80 promoter activity was determined 48 h later as described in Materials and Methods. (B and C) Effect of ICP22 on BMDCs. BMDCs were transfected with either EV-pcDNA or ICP22-pcDNA for 24 h as described in Materials and Methods. Transfected cells were stained with anti-CD11c and anti-CD80 or with anti-CD11c and anti-CD86 antibodies, and the effects of ICP22 on CD80 (B) and CD86 (C) expression were determined by flow cytometric analysis. Each point represents the mean ± SEM from three separate experiments (n = 9). Statistical analyses were done using ANOVA to test for P values.

We next tested whether ICP22 alone could inhibit CD80 expression activity in DCs. BMDCs were transfected with ICP22 or empty vector (EV) DNA for 24 h, and the effects of ICP22 transfection of BMDCs on CD80 expression by the DCs were determined by FACS analysis. Our results suggest that transfection of BMDCs by ICP22 DNA significantly reduced the population of CD80+ CD11c+ cells compared to that in cells that were transfected with empty vector DNA (Fig. 6B) (P = 0.003). In contrast, the population of CD86+ CD11c+ cells increased in ICP22 transfected cells compared to that in empty vector-transfected cells (Fig. 6C) (P < 0.01). These results suggest that ICP22 may be involved in downregulating CD80 expression but not that of CD86 through reducing its promoter activity, but these experiments still do not rule out the involvement of early genes.

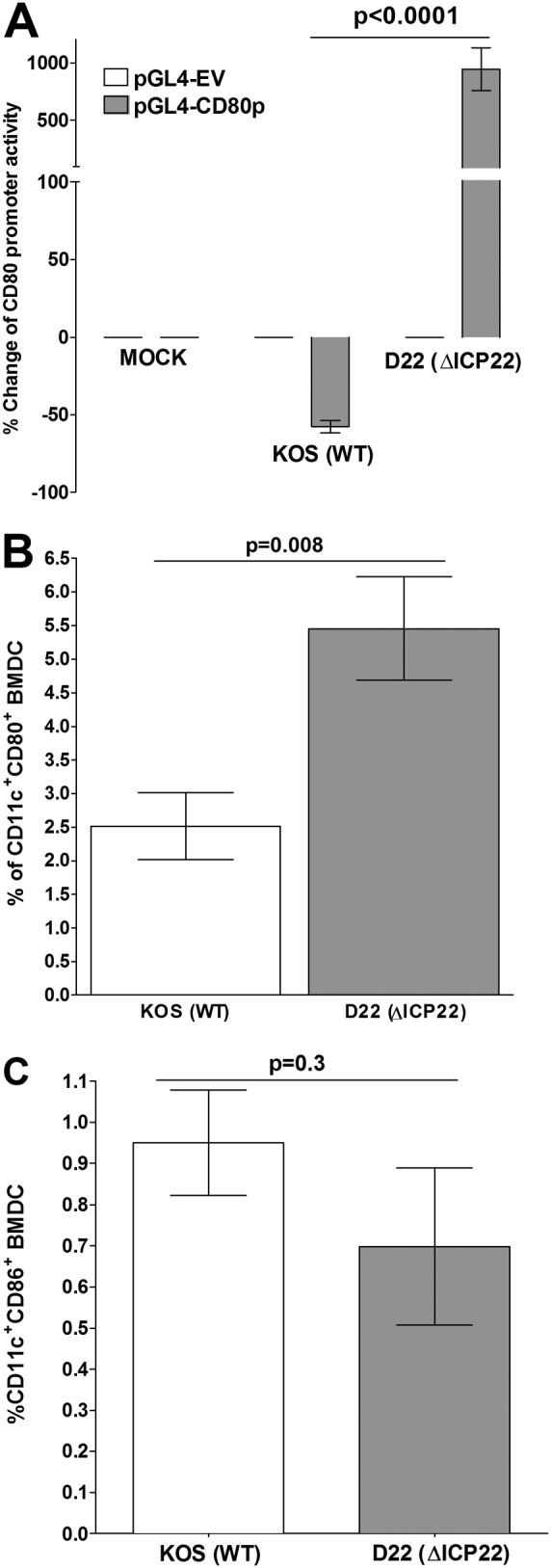

An ICP22-null mutant virus enhances CD80 promoter activity.

As proof of principle that only ICP22 and no other genes are involved in suppression of CD80 promoter, we tested the effects of an ICP22-null virus on CD80 promoter activity. We transfected HEK 293 cells with pGL4-EV or pGL4-CD80p plasmid for 48 h and then infected the transfected cells with 10 PFU/cell of D22 (ΔICP22), which lacks the ICP22 gene, or the wild-type (WT) KOS parental virus for 24 h prior to measurement of the CD80 promoter activity. The results confirmed that the CD80 promoter activity was significantly lower (∼60%) in the cells infected with WT KOS than in mock-infected cells (Fig. 7A) (P < 0.0001). In contrast, infection with the mutant D22 virus increased CD80 promoter activity by more than 900% compared with activity after infection with WT virus (Fig. 7A). The differences between the results in WT KOS and D22 were highly significant (Fig. 7A) (P < 0.0001). These results confirmed the overall hypothesis that ICP22 is involved in the suppression of CD80 expression.

FIG 7.

Effects of an ICP22 deletion mutant HSV-1 virus on CD80 expression. (A) Effects of ICP22 deletion virus in transfected HEK 293 cells. HEK 293 cells were transfected with either pGL4-EV or pGL4-CD80p DNA and 24 h later were infected with 10 PFU/cell of D22 (ΔICP22) virus that lacks the ICP22 gene or its KOS parental virus or were mock infected for 24 h. CD80 promoter activity was determined at 24 h p.i. as described in Materials and Methods. (B and C) Effect of ICP22 deletion virus in BMDCs. BMDCs were infected with 10 PFU/cell of D22 or KOS as described for panel A for 24 h. At 24 h p.i., infected BMDCs were stained with anti-CD11c and anti-CD80 antibodies or anti-CD11c and anti-CD80 antibodies, and the effects of ICP22 deletion on CD80 (B) and CD86 (C) were determined by flow cytometric analysis. Each point represents the mean ± SEM from three separate experiments with three replications (n = 9). Statistical analyses were done using ANOVA to test for P values.

The effects of the ICP22-null virus on blocking the expression of the CD80 promoter were further tested using BMDCs. BMDCs were infected with 10 PFU/cell of D22 or WT KOS for 24 h. In these experiments, the effects in infected BMDCs of the absence of ICP22 knockout virus on CD80 expression by the DCs were determined by FACS analysis. We found that the population of CD11c+ CD80+ cells was significantly larger in BMDCs infected with D22 than in BMDCs infected with WT KOS (Fig. 7B) (P < 0.008). No significant differences were detected in the sizes of the population of CD11c+ CD86+ cells among BMDCs that were infected with D22 or KOS (Fig. 7C) (P < 0.3). These results further suggest that in the absence of ICP22, CD80 expression is upregulated while ICP22 had no effect on CD86 expression.

ICP22 binds the CD80 promoter.

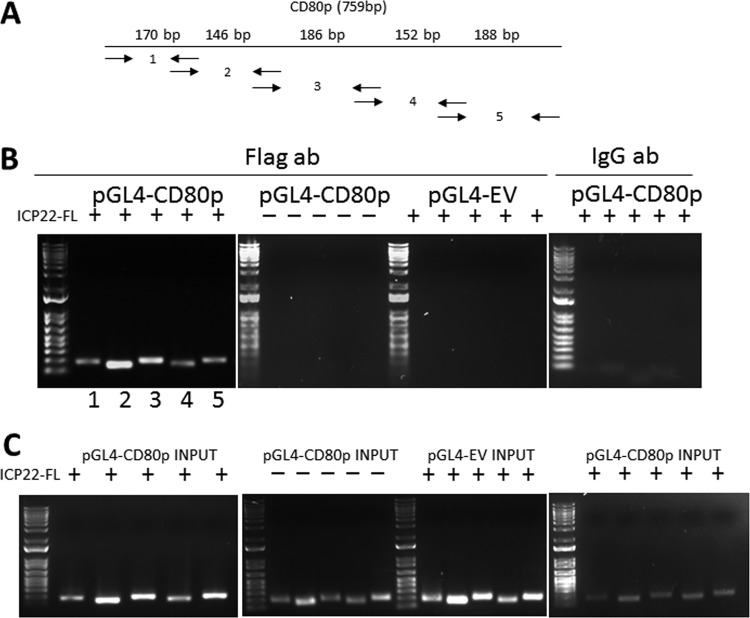

Since ICP22 must bind to a region of the CD80 promoter to exert its effects on promoter activity, we characterized ICP22 binding to the CD80 promoter using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP). We first stimulated the cells by transfecting HEK 293 cells with pGL4-CD80p, pGL4-EV, and pCDNA3.1-ICP22-FLAG (ICP22-FL). In the ChIP protocol, ICP22-FL-bound chromatin was pulled down using an anti-FLAG antibody, and the sequestered chromatin was used as the template for a PCR. Five sets of primers were used that spanned the 759-bp region of the CD80 promoter as shown in Fig. 8A. Gel electrophoresis of PCRs revealed enrichment of two primer pairs, pair 2 (146 bp) and pair 3 (186 bp). As shown in Fig. 8B, pair 2 developed a stronger band than pair 3. No PCR products were detected in our controls that included pGL4-EV transfected cells, pGL4-CD80p cells without pCDNA3.1-ICP22-FL transfection, or pGL4-CD80p cells with pCDNA3.1-ICP22-FL pulled down by an unspecific IgG antibody (Fig. 8B). In PCR readouts of input chromatin, we found the expected PCR amplicons in pGL4-CD80p input with or without pCDNA3.1-ICP22-FL and in pGL4-EV with pCDNA3.1-ICP22-FL (Fig. 8C). As expected, analysis of pGL4-CD80p input pulled down by IgG isotype control antibody did yield PCR products for each of the primer pairs without any enrichment. Overall, the enrichment of amplicons using two sets of primers suggests the presence of a putative binding site for ICP22 on the CD80 promoter that falls between positions 151 and 462 of the CD80 promoter (see the boldface sequence of the CD80 promoter in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). There is a 60% sequence homology between this region of mouse CD80 promoter and that of human CD80 promoter.

FIG 8.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) of ICP22-bound chromatin. (A) Schematic of the primers pairs used for PCR of the five sections of the CD80 promoter. Primer pairs are designated with arrows that represent forward and reverse primers with corresponding expected product sizes, which are positioned over the corresponding region (e.g., primer pair 1 has a size of 170 bp). (B) Chromatin immunoprecipitation and PCR amplification of CD80 promoter. Subconfluent HEK 293 cells were transfected with either pGL4-CD80p or pGL4-EV and pCDNA3.1-ICP22-FLAG (FL), in combinations as described in Materials and Methods. Transfected cells were harvested and lysed, and the lysate was sheared by sonication and prepared for pulldown. Protein G magnetic beads were incubated with anti-FLAG antibody, and the lysates were incubated overnight at 4°C. A stationary magnet was used to immobilize the chromatin-FLAG-MAb-protein G magnetic bead complex, and subsequent elution, reverse cross-linking, and proteinase K completed the preparation of the chromatin template. The PCR products were loaded on a 1% agarose gel along with a 1-kb Plus ladder (Invitrogen). The FLAG antibody pulldown of samples was transfected using the following plasmids: pGL4-CD80p and pCDNA3.1-ICP22-FL, pGL4-CD80p alone, and pGL4-EV with pCDNA3.1-ICP22-FL. An isotype IgG control pulldown with pGL4-CD80p and pCDNA3.1-ICP22-FL was included. (C) PCR experiments of input chromatin. The PCR experiment utilized chromatin templates that did not undergo FLAG pulldown but otherwise were similar with regard to primers used and transfection combinations, as described above. The putative binding site for ICP22 on the CD80 promoter falls between positions 151 and 462 of the CD80 promoter, and the total fragment size for the two primer sets involved (set 2 and set 3), which includes the primers, is 311 bp (the CD80 promoter sequence is shown in bold in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

Exacerbation of CS after ocular infection with a recombinant HSV-1 expressing the murine CD80 gene under regulation by the LAT promoter.

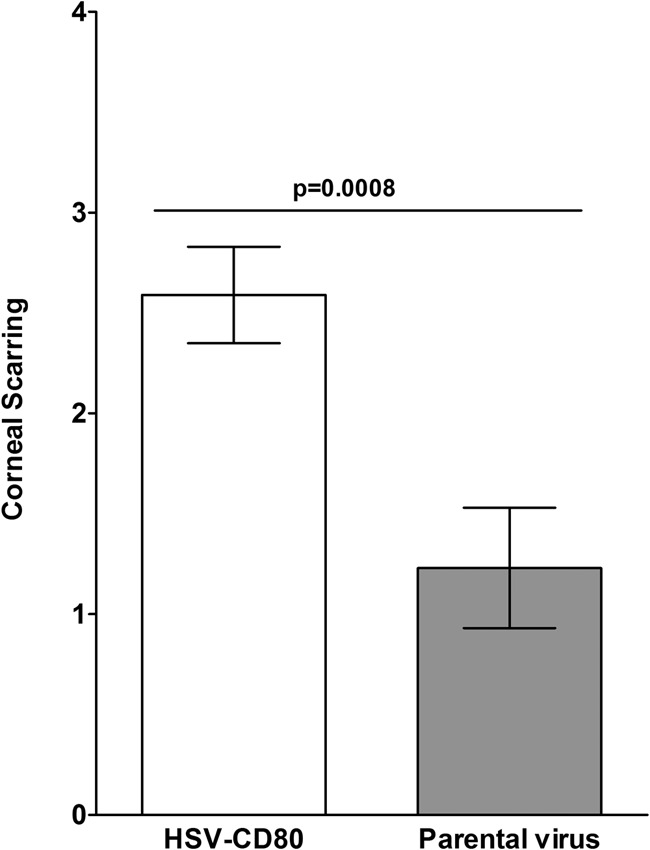

Previously, we reported the construction and characterization of a recombinant HSV-1 expressing two copies of murine CD80 under the control of the latency-associated transcript (LAT) promoter in vitro (19). We used this recombinant virus to determine if overexpression of CD80 in the eye affects corneal scarring (CS) after ocular infection. In these experiments, BALB/c mice, which are susceptible to HSV-1 infection, were ocularly infected with 1 × 105 PFU per eye of HSV-CD80 or the parental dLAT2903 strain. Mortality of HSV-CD80-infected mice (17 of 30 mice [57%]) versus that of parental virus-infected mice (13 of 20 [65%]) did not establish statistically significant differences (P > 0.05, Fisher's exact test). HSV-CD80-infected mice presented with significantly more corneal scarring than parental virus-infected mice at 28 days postinfection (Fig. 9) (P = 0.0008, Student's t test). Thus, overexpression of CD80 in ocularly infected mice exacerbated CS in mice.

FIG 9.

Corneal scarring in mice infected ocularly with HSV-CD80. BALB/c mice were ocularly infected with 1 × 105 PFU/eye of HSV-CD80 or its parental virus. Corneal scarring (CS) in surviving mice was examined on day 28 p.i. as described in Materials and Methods. The CS score represents the average ± SEM from 34 and 26 eyes for HSV-CD80 and parental virus infection, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that HSV-1 significantly reduces the expression of CD80 in the corneas of ocularly infected mice. This modulation was not associated with a generalized depression of the immune response but was targeted in that it affected CD80 but not CD86 and preferentially affected expression of CD80 by the DCs. Furthermore, the suppression of CD80 expression correlated with the presence of infectious virus. The results demonstrated that the suppression of CD80 is mediated specifically by HSV-1 ICP22, which binds to the promoter region of CD80. Taken together with the finding that infection of mice with HSV-CD80 exacerbated corneal scarring, these results suggest that that HSV-1 uses the ICP22-CD80 interaction as a critical immune evasion mechanism.

HSV-1 encodes at least 85 genes (32), and HSV-1 replication is orchestrated by a cascade of three sets of genes (29, 33). The five immediate early genes encode infected cell proteins that are expressed without de novo protein synthesis: ICP0, ICP4, ICP22, ICP27, and ICP47 (29, 33). The initial steps of replication begin with these five ICP proteins, and together, they comprise the set of immediate early genes that work in concert with preexisting viral proteins and host replication machinery. In this study, we have shown that the HSV-1 repression of CD80 in DCs is mediated by the immediate early gene ICP22 and that none of the other HSV-1 genes contribute to the suppression of CD80 expression. Indeed, transfection with ICP0, ICP27, or ICP47 significantly increased CD80 promoter activity although these increases did not neutralize the effects of ICP22 suppression of CD80. The massive increase in CD80 promoter activity observed on infection with D22 HSV-1 virus, which lacks ICP22, increases confidence in the conclusion that ICP22 alone can counteract the stimulatory effects of other immediate early genes on CD80 expression. ICP22 is indispensable for virus replication in vivo but not in vitro (34). It is composed of 420 amino acids encoded by the US1 gene, and an alternative form, the US1.5 gene, is characterized as N-terminally truncated (35). It has been shown that ICP22 interacts with and blocks the recruitment of the positive transcription elongation factor βb (P-TEFβ) to viral promoter regions (36). Our finding that ICP22 mediates downregulation of CD80 expression through binding to the promoter and blockade of transcription of CD80 is consistent with this previous report.

CD80 is expressed by several different cell types (37). In this study, HSV-1 infection appeared to preferentially downregulate CD80 expression by DCs. HSV-1 infection was found to consistently downregulate expression of CD80 by DCs irrespective of the source of the DCs (cornea, spleen, or BMDCs). In contrast, HSV-1 infection did not affect CD80 expression by macrophages, T cells, or monocytes in either the cornea or the spleen. However, the effects of HSV-1 infection on the expression of CD80 by B cells appear to be more complex. Downregulation of CD80 was observed in the population of B cells in isolated spleen cells of naive mice following infection with HSV-1 in vitro but not after ocular infection in vivo. These discrepancies may reflect tissue-specific differences in B cell biology or representation of B cell subtypes. They do, however, suggest that the downregulation of CD80 requires the presence of the virus in the tissue and is not mediated by systemic effects.

In this study, as proof of principle that higher levels of CD80 expression may have pathogenic consequences, we ocularly infected BALB/c mice with a recombinant HSV-CD80 virus which has two copies of the CD80 gene under the regulation of the LAT promoter (19). Differences in levels of neurovirulence related to infection with this recombinant virus and that of the parental HSV-1 dLAT2903 were negligible. However, infection with the recombinant virus was associated with significantly greater levels of CS. A hallmark of HSV-1 ocular infection is CS, which is the result of immune responses triggered by the virus (13, 38–42). Adoptive transfer, T cell depletion, and knockout mouse studies of CD8+ T cells alone (13, 43–45), CD4+ T cells alone (11, 14, 46, 47), or a combination of these (16, 46, 48) are involved in herpes-induced corneal scarring. The activation of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells during immune responses depends on preferential utilization of CD80 and CD86 (49–55). Development of the T cell immune responses is dependent on the binding of CD28 on the T cells to CD80 (B7-1) or CD86 (B7-2) on APCs (56). In addition to binding to CD28 and CTLA-4, CD80 also binds to programmed death-1 ligand (PD-L1) on the DCs (18, 19). The CD80–CTLA-4 pathway leads to repression of T cell activation, and the CD80-CD28 pathway potentiates T cell activation. Since CTLA-4 displays a preferential affinity for CD80, an imbalance in the signaling due to diminished expression of CD80 could sway the overall response toward T cell activation through the CD80-CD28 and/or CD80–PD-L1 interaction. Thus, overexpression of CD80 in the eye may prolong the immune response in the eye, leading to greater eye disease.

Previously, it has been shown that CD86 initiates the primary immune responses, whereas CD80 is considered to be of greater importance in prolonging the primary immune responses and in costimulation of secondary immune responses (20, 21, 24, 57). In this study, in contrast to suppression of CD80 by HSV-1 and specifically by the ICP22 gene, CD86 was not affected. CD80 increases the generation of CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) (58). Since both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are implicated in corneal scarring, higher expression of CD80 in the eye may contribute to T cell activation and expansion as well as to increasing the migration of inflammatory cells into the cornea, leading to exacerbation of eye disease. Thus, these results support the idea that ectopic CD80 expression increases T cell responses in the eye of ocularly infected mice and further enhances eye disease. Previously, we have shown that ectopic expression of CD80 by HSV-1 increased CD80 binding to PD-L1 on DCs, allowing efficient infection and lysis of infected cells (19). Recently it was reported that PD-L1−/− mice had lower virus replication in their eyes than WT mice, suggesting that PD-L1 expression on corneal cells negatively impacts the ability of the innate immune system to clear HSV-1 from infected corneas (59). This report is in line with our results of exacerbation of CS in HSV-CD80-infected mice due to the binding of HSV-CD80 to PD-L1 in the cornea (19). The current results concerning the pathogenic effects observed on ocular infection with the recombinant HSV-CD80 are compatible with the previous report that subcutaneous immunization of mice with a recombinant HSV-1 expressing either CD80 or CD86 molecules enhanced vaccine efficacy against ocular HSV-1 infection with WT virus (60). Taken together with the report that CD80 significantly modulates immunity and improves graft survival (61), the current results suggest that CD80 can promote pathogenic or protective immune responses in a context-dependent manner.

Immune escape mechanisms are used by many infectious agents to evade innate and adaptive immunity. HSV appears to utilize several such strategies. The HSV immediate early protein ICP47 fosters blocking of cytotoxic T cell detection of infected cells (62, 63). In the absence of its E3 ubiquitin ligase function, ICP0 directly mediates the degradation of the cell surface protein CD83, which is an important activator of DCs (64). Through its E3 ligase function, ICP0 also reduces Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2)-mediated inflammatory responses and NF-κB signaling (65). Viral gE independently (66) or as a gE/gI complex binds the Fc domain of IgG (66, 67), thereby blocking or altering the function of antibodies during cytolysis (68). gC is a regulatory protein that aids in the survival of the HSV-1 virus (69, 70), and it has been reported that recombinant viruses lacking gC produce lower eye disease in ocularly infected rabbits than infection with WT parental virus (71). The precise biological function of C3b and Fc binding is unknown, but in vivo murine experiments suggest that these interactions with the immune system may modulate the immune response to the virus, thus allowing the virus to partially escape immune surveillance (72, 73). Our current findings reveal an additional mechanism of immune escape that has important ramifications for the host adaptive immune response.

In conclusion, we provided new evidence of a strategy by which HSV-1 subverts the immune response through the promoter-specific downregulation of CD80 by ICP22. The inhibition of CD80 expression on DCs mediated by HSV-1 ICP22 may reduce the inflammatory response in the cornea that leads to keratitis and corneal inflammation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses, cells, and mice.

Triple-plaque-purified WT McKrae, dLAT2903 (parental virus for HSV-CD80), and HSV-CD80 viruses were used in this study, as we described previously (19). The D22 recombinant virus with an ICP22 deletion, which was described previously (35), and the KOS parental virus were provided by David Davido, University of Kansas. The D22 virus was constructed from parental KOS by inserting the lacZ gene (β-galactosidase) in place of the ICP22 open reading frame (ORF) starting at the internal repeat short (IRS) sequence and extending to unique short sequence (US) (35). Rabbit skin (RS) cells (used for the preparation of virus stocks) were grown in Eagle's minimal essential medium (EMEM) supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum (FCS). Transfection studies were carried out using HEK 293 cells (ATCC) cultured in EMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Cells were typically passaged at 80% confluence and grown in a 37°C incubator and at 5% CO2. Female 6-week-old inbred BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME.) were used. The C57BL/6 mice were used as the source of bone marrow (BM) for the generation of mouse DCs (BMDCs) as we described previously (74). Single-cell suspensions of spleen cells from individual mice were prepared as we described previously (75). The animal research protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center (protocol 5030).

Plasmids.

Plasmids containing ICP0, ICP4, ICP22, and ICP27 were generously donated by D. J. Davido (35, 76–79), while the ICP47-containing plasmid was a gift from David Johnson (80). The complete ORFs of the five immediate early genes were cloned into pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA) as we described previously (81). The 759 bp of the CD80 promoter (82) and the 700-bp promoter region of CD86 were synthesized (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ) and inserted into the multiple cloning site of pGL4 to drive expression of the luciferase reporter under the CD80 or CD80 promoter, respectively (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material for the promoters). We refer to these plasmids as pGL4-80p and pGL4-86p. In addition, we synthesized ICP22-FLAG (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ) based on the published sequences of HSV-1 (32). This construct contains the complete ORF of the ICP22 gene (1,260 bp) and two copies of FLAG sequences inserted into the BamH1 site of pcDNA3.1 (Fig. S1, ICP22-FLAG).

Transfection.

Transfection experiments were carried out using HEK 293 cells and Gene Porter 2 (Genlantis, San Diego, CA). Briefly, cells were grown to 70% to 80% confluence in 12-well plates. Immediately before the experiment, plasmids were diluted in the dilution buffer provided, and the transfection reagents were resuspended in EMEM (no FBS) in separate tubes. The reagents were then combined, incubated for 5 min, and added to the plates. The cells were transfected with either promoterless luciferase plasmid pGL4-empty vector (EV) or pGL4-CD80p, which had 759 bp of the CD80 promoter (82) cloned at the multiple cloning site of pGL4 to drive expression of the luciferase reporter (Fig. S1). pRL-SV40 (catalog number E2231; Promega), a Renilla luciferase reporter plasmid, was used as the cotransfected internal control to monitor baseline responses of cells to transfection (10 ng/reaction). In this dual luciferase reporter (DLR) system (Promega, Madison, WI), two individual reporters are introduced simultaneously to determine the response within the same cells. Sample preparation was carried out as described by the manufacturer (Promega). Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in lysis buffer, and the supernatants were collected and transferred to 96-well plates. The luminometer (Glomax; Promega, Madison, WI) was primed with the luciferase and Stop & Glow reagents. Assays were carried out in replicates of three and means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) were calculated from three separate experiments.

Infection of BMDCs and spleen cells with HSV-1.

BMDCs and spleen cells were infected with 0.1 or 1 PFU/cell of HSV-1 strain McKrae or mock infected for 24 h. At 24 h postinfection (p.i.), the cells were harvested for FACS analysis.

FACS analysis.

Infected or mock-infected BMDCs or spleen cells were incubated with Fc blocker (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), washed in PBS with 5% FBS, and then stained with anti-mouse CD45R/B220 BV510 (catalog number 103248), anti-mouse CD11b-AF700 (101222), anti-mouse CD11c-BV421 (117330), anti-mouse CD86-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (105006), anti-mouse CD80-phycoerythrin (PE) (104708), and anti-mouse F4/80-allophycocyanin (APC) ( 123116), all from BioLegend (San Diego, CA), for 1 h. Stained cells were washed (1 ml of PBS with 0.1% sodium azide) and centrifuged, and the pelleted cells were resuspended in PBS with 0.1% sodium azide with 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD) (catalog number 420404; BioLegend). Stained cells were analyzed using a BD LSR II flow cytometer and BD FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences). Postexperiment analysis of data was performed using FlowJo software (TreeStar).

Ocular infection of mice.

BALB/c or C57BL/6 mice were infected ocularly with 2 μl of tissue culture medium containing 2 × 105 PFU/eye of the HSV-1 strain McKrae without corneal scarification.

FACS analysis of infected cornea.

On day 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or 7 p.i. for C57BL/6 mice, the infected mice were euthanized, and the corneas from each mouse were harvested and combined. The corneas were digested in PBS containing collagenase type I (3 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), as we described previously (83). Single-cell suspensions were stained with anti-CD11b, anti-CD11c, anti-CD86, anti-CD80, and anti-F4/80 antibodies, and FACS was analysis performed as described above.

Detection of virus in tears of infected mice.

Tear films were collected from both eyes of 10 C57BL/6 mice per group on days 1 to 7 p.i. using a Dacron-tipped swab as described previously (84). Each swab was placed in 1 ml of MEM tissue culture medium and squeezed, and the amount of virus was determined using a standard plaque assay on RS cells.

Monitoring corneal scarring.

The severity of corneal scarring in surviving BALB/c mice was scored in a masked fashion by administration of 1% fluorescein and examination using a slit-lamp biomicroscope. Severity was scored on a scale of 0 to 4 for corneal staining or involvement (0, no disease; 1, 25%; 2, 50%; 3, 75%; 4, 100%).

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and Southern analysis of RNA from corneas of immunized and infected mice.

BALB/c mice were inoculated intramuscularly (i.m.) in each quadricep on days 0, 21, and 42 with a cocktail of DNA representing the five HSV-1 glycoproteins (gB, gC, gD, gE, and gI) consisting of 10 μg of each cesium chloride-purified DNA (50 μg DNA in a total volume of 100 μl) using a 27-gauge needle as we described previously (27). A second group of mice was inoculated intraperitoneally (i.p.) on the same schedule with 2 × 105 PFU of live avirulent HSV-1 strain KOS. A third group of mice was not inoculated. Three weeks after the third injection, each of the groups was randomly subdivided. Half of the mice were infected ocularly with 2 × 105 PFU/eye of virulent HSV-1 strain McKrae, and half were mock infected and used as a mock control. On day 5 p.i., the corneas from three mice per group were harvested and examined to confirm the lack of contamination from other parts of the mouse eye, vitreous fluid, and tears. The corneas were then combined and processed for RNA extraction using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and cDNA synthesis as we described previously (19, 83). cDNA was separated using a 0.9% agarose gel and transferred to Zeta paper, and DNA-DNA hybridization was carried out using 32P-labeled CD80 or CD86 as we described previously (85). β-Actin was used as a control.

Effect of HSV-1 infection on CD80 promoter activity.

BMDCs were transfected with pGL4-CD80p or pGL4-EV for 24 h. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were washed and resuspended in culture medium containing 0.01, 0.1, or 1 PFU/cell of HSV-1 strain McKrae. At 72 h p.i., cells were harvested, lysed, and prepared for analysis of luciferase activity as described by the manufacturer (Promega, Madison, WI).

Roscovitine treatment.

Roscovitine (Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX) was used to investigate the effects of expression of immediate early genes of HSV-1 on CD80 promoter activity. Roscovitine (100 μM) specifically inhibits the immediate early genes of HSV-1 (30). HEK 293 cells were grown to 80% confluence and transfected with pGL4-CD80p or pGL4-EV. After 3 days, roscovitine (100 μM) was added 30 min prior to infection with WT HSV-1 at 1 PFU/cell. After 1 h, cell lysates were prepared for luciferase promoter analysis using the DLR system from Promega. To assess if the effects of roscovitine could rescue the CD80 promoter activity, we also delayed addition of roscovitine until 4 h p.i. or 6 h p.i. with WT virus.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation.

Cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1-ICP22-FL combined with either pGL4-EV or pGL4-CD80p. Two days later they were processed for ChIP analysis using a ChIP-IT Express kit as described by the manufacturer (catalog number 53008; Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA). The transfected cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, washed with 1× PBS, and treated with the 1× glycine fix solution. Cells were washed again and then harvested and spun down in PBS. Pelleted cells were treated with phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and proteinase inhibitors provided by the manufacturer and homogenized using a Dounce homogenizer. The chromatin lysates were then subjected to several cycles of 20 s of sonication/30 s of rest on ice in Vibra-Cell ultrasonic liquid processors (Sonics). The lysates were centrifuged for 10 min at 5,000 rpm and 4°C in a microcentrifuge, and the supernatant was collected. An aliquot of supernatant was set aside as the input control (chromatin prior to enrichment by ICP22-FLAG pulldown). The rest was incubated with protein G magnetic beads with anti-FLAG M2 mouse monoclonal antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) or IgG isotype control (Sigma-Aldrich), along with ChIP buffer 1, protease inhibitors, and water. After incubation on a rotator overnight at 4°C, the chromatin-antibody-magnetic beads complexes were washed twice with ChIP wash buffers, utilizing the provided magnet to station the magnetic beads while the untethered chromatin was removed. Finally, chromatin was eluted, reverse cross-linked and treated with proteinase K for analysis by PCR. The PCR was prepared using five primer sets that span the 759-bp upstream promoter of CD80 (82). The ChIP product was amplified using the following primers: set 1 forward, 5′-GCTCCTTACTTTCTTACTTTCTTTCTTTTCTG-3′; set 1 reverse, 5′-TGGTGGTGCACACCTTTAAT-3′; set 2 forward, 5′-ATTAAAGGTGTGCACCACCA-3′; set 2 reverse, 5′-CCACGTTACGAACACCACTTA-3′; set 3 forward, 5′-TAAGTGGTGTTCGTAACGTGG-3′; set 3 reverse, 5′-GACACAGAGTGACTGCCAAA-3′; set 4 forward, 5′-TTTGGCAGTCACTCTGTGTC-3′; set 4 reverse, 5′-GCGGGGGTGGGGTGACTAA-3′; set 5 forward 5′-TTAGTCACCCCACCCCCGC-3′; and set 5 reverse, 5′-CGAGCCCAGTAGCTCTATCTTA-3′. PCR used Taq polymerase (NEB) to amplify the regions (the amplicon sizes are shown in Fig. 9A). PCRs were loaded onto a 1% agarose gel and subjected to DNA electrophoresis.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed by a Student's t test, Fisher's exact test, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) using GraphPad (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Results were considered statistically significant at a P value of <0.05.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by Public Health Service NIH grants EY026944, EY13615, and EY029160.

We thank David Davido and David Johnson for the gifts of plasmids and viruses.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01803-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barron BA, Gee L, Hauck WW, Kurinij N, Dawson CR, Jones DB, Wilhelmus KR, Kaufman HE, Sugar J, Hyndiuk RA, Laibson PR, Stulting RD, Asbell PA, for the Herpetic Eye Disease Study Group. 1994. Herpetic eye disease study. A controlled trial of oral acyclovir for herpes simplex stromal keratitis. Ophthalmology 101:1871–1882 doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(13)31155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilhelmus KR, Dawson CR, Barron BA, Bacchetti P, Gee L, Jones DB, Kaufman HE, Sugar J, Hyndiuk RA, Laibson PR, Stulting RD, Asbell PA. 1996. Risk factors for herpes simplex virus epithelial keratitis recurring during treatment of stromal keratitis or iridocyclitis. Herpetic Eye Disease Study Group. Br J Ophthalmol 80:969–972. doi: 10.1136/bjo.80.11.969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liesegang TJ. 1999. Classification of herpes simplex virus keratitis and anterior uveitis. Cornea 18:127–143. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199903000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liesegang TJ. 2001. Herpes simplex virus epidemiology and ocular importance. Cornea 20:1–13. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200101000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill TJ. 1987. Ocular pathogenicity of herpes simplex virus. Curr Eye Res 6:1–7. doi: 10.3109/02713688709020060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young RC, Hodge DO, Liesegang TJ, Baratz KH. 2010. Incidence, recurrence, and outcomes of herpes simplex virus eye disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1976–2007: the effect of oral antiviral prophylaxis. Arch Ophthalmol 128:1178–1183. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dawson CR. 1984. Ocular herpes simplex virus infections. Clin Dermatol 2:56–66. doi: 10.1016/0738-081X(84)90066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wechsler SL, Nesburn AB, Watson R, Slanina S, Ghiasi H. 1988. Fine mapping of the major latency-related RNA of herpes simplex virus type 1 in humans. J Gen Virol 69:3101–3106. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-12-3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phelan D, Barrozo ER, Bloom DC. 2017. HSV1 latent transcription and non-coding RNA: a critical retrospective. J Neuroimmunol 308:65–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mercadal CM, Bouley DM, DeStephano D, Rouse BT. 1993. Herpetic stromal keratitis in the reconstituted scid mouse model. J Virol 67:3404–3408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newell CK, Martin S, Sendele D, Mercadal CM, Rouse BT. 1989. Herpes simplex virus-induced stromal keratitis: role of T-lymphocyte subsets in immunopathology. J Virol 63:769–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hendricks RL, Janowicz M, Tumpey TM. 1992. Critical role of corneal Langerhans cells in the CD4- but not CD8-mediated immunopathology in herpes simplex virus-1-infected mouse corneas. J Immunol 148:2522–2529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hendricks RL, Tumpey TM. 1990. Contribution of virus and immune factors to herpes simplex virus type I- induced corneal pathology. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 31:1929–1939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manickan E, Francotte M, Kuklin N, Dewerchin M, Molitor C, Gheysen D, Slaoui M, Rouse BT. 1995. Vaccination with recombinant vaccinia viruses expressing ICP27 induces protective immunity against herpes simplex virus through CD4+ Th1+ T cells. J Virol 69:4711–4716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hendricks RL, Epstein RJ, Tumpey T. 1989. The effect of cellular immune tolerance to HSV-1 antigens on the immunopathology of HSV-1 keratitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 30:105–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghiasi H, Cai S, Perng GC, Nesburn AB, Wechsler SL. 2000. Both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are involved in protection against HSV-1 induced corneal scarring. Br J Ophthalmol 84:408–412. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.4.408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ. 2002. The B7-CD28 superfamily. Nat Rev Immunol 2:116–126. doi: 10.1038/nri727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Butte MJ, Keir ME, Phamduy TB, Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ. 2007. Programmed death-1 ligand 1 interacts specifically with the B7-1 costimulatory molecule to inhibit T cell responses. Immunity 27:111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mott KR, Allen SJ, Zandian M, Akbari O, Hamrah P, Maazi H, Wechsler SL, Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ, Ghiasi H. 2014. Inclusion of CD80 in HSV targets the recombinant virus to PD-L1 on DCs and allows productive infection and robust immune responses. PLoS One 9:e87617. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lenschow DJ, Su GH, Zuckerman LA, Nabavi N, Jellis CL, Gray GS, Miller J, Bluestone JA. 1993. Expression and functional significance of an additional ligand for CTLA-4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90:11054–11058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hathcock KS, Laszlo G, Pucillo C, Linsley P, Hodes RJ. 1994. Comparative analysis of B7-1 and B7-2 costimulatory ligands: expression and function. J Exp Med 180:631–640. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.2.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inaba K, Witmer PM, Inaba M, Hathcock KS, Sakuta H, Azuma M, Yagita H, Okumura K, Linsley PS, Ikehara S, Muramatsu S, Hodes RJ, Steinman RM. 1994. The tissue distribution of the B7-2 costimulator in mice: abundant expression on dendritic cells in situ and during maturation in vitro. J Exp Med 180:1849–1860. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larsen CP, Ritchie SC, Hendrix R, Linsley PS, Hathcock KS, Hodes RJ, Lowry RP, Pearson TC. 1994. Regulation of immunostimulatory function and costimulatory molecule (B7-1 and B7-2) expression on murine dendritic cells. J Immunol 152:5208–5219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freeman GJ, Gray GS, Gimmi CD, Lombard DB, Zhou LJ, White M, Fingeroth JD, Gribben JG, Nadler LM. 1991. Structure, expression, and T cell costimulatory activity of the murine homologue of the human B lymphocyte activation antigen B7. J Exp Med 174:625–631. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.3.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borriello F, Sethna MP, Boyd SD, Schweitzer AN, Tivol EA, Jacoby D, Strom TB, Simpson EM, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. 1997. B7-1 and B7-2 have overlapping, critical roles in immunoglobulin class switching and germinal center formation. Immunity 6:303–313. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80333-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang TT, Jabs C, Sobel RA, Kuchroo VK, Sharpe AH. 1999. Studies in B7-deficient mice reveal a critical role for B7 costimulation in both induction and effector phases of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med 190:733–740. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.5.733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Osorio Y, Cohen J, Ghiasi H. 2004. Improved protection from primary ocular HSV-1 infection and establishment of latency using multigenic DNA vaccines. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 45:506–514. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghiasi H, Hofman FM, Wallner K, Cai S, Perng G, Nesburn AB, Wechsler SL. 2000. Corneal macrophage infiltrates following ocular herpes simplex virus type 1 challenge vary in BALB/c mice vaccinated with different vaccines. Vaccine 19:1266–1273. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(00)00298-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Honess RW, Roizman B. 1974. Regulation of herpesvirus macromolecular synthesis. I. Cascade regulation of the synthesis of three groups of viral proteins. J Virol 14:8–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schang LM, Rosenberg A, Schaffer PA. 2000. Roscovitine, a specific inhibitor of cellular cyclin-dependent kinases, inhibits herpes simplex virus DNA synthesis in the presence of viral early proteins. J Virol 74:2107–2120. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.5.2107-2120.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schang LM, Rosenberg A, Schaffer PA. 1999. Transcription of herpes simplex virus immediate-early and early genes is inhibited by roscovitine, an inhibitor specific for cellular cyclin-dependent kinases. J Virol 73:2161–2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGeoch DJ, Dalrymple MA, Davison AJ, Dolan A, Frame MC, McNab D, Perry LJ, Scott JE, Taylor P. 1988. The complete DNA sequence of the long unique region in the genome of herpes simplex virus type 1. J Gen Virol 69:1531–1574. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-7-1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roizman B, Zhou G. 2015. The 3 facets of regulation of herpes simplex virus gene expression: A critical inquiry. Virology 479–480:562–567. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poffenberger KL, Idowu AD, Fraser-Smith EB, Raichlen PE, Herman RC. 1994. A herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP22 deletion mutant is altered for virulence and latency in vivo. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung 41:51–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mostafa HH, Davido DJ. 2013. Herpes simplex virus 1 ICP22 but not US 1.5 is required for efficient acute replication in mice and VICE domain formation. J Virol 87:13510–13519. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02424-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guo L, Wu WJ, Liu LD, Wang LC, Zhang Y, Wu LQ, Guan Y, Li QH. 2012. Herpes simplex virus 1 ICP22 inhibits the transcription of viral gene promoters by binding to and blocking the recruitment of P-TEFb. PLoS One 7:e45749. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sansom DM. 2000. CD28, CTLA-4 and their ligands: who does what and to whom? Immunology 101:169–177. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00121.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Metcalf JF, Kaufman HE. 1976. Herpetic stromal keratitis-evidence for cell-mediated immunopathogenesis. Am J Ophthalmol 82:827–834. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(76)90057-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dix RD. 2002. Pathogenesis of herpes simplex ocular disease, vol 2 Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brandt CR. 2005. The role of viral and host genes in corneal infection with herpes simplex virus type 1. Exp Eye Res 80:607–621. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomas J, Rouse BT. 1997. Immunopathogenesis of herpetic ocular disease. Immunol Res 16:375–386. doi: 10.1007/BF02786400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rowe AM, St Leger AJ, Jeon S, Dhaliwal DK, Knickelbein JE, Hendricks RL. 2013. Herpes keratitis. Prog Retin Eye Res 32:88–101. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oakes JE, Rector JT, Lausch RN. 1984. Lyt-1+ T cells participate in recovery from ocular herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 25:188–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagafuchi S, Hayashida I, Higa K, Wada T, Mori R. 1982. Role of Lyt-1 positive immune T cells in recovery from herpes simplex virus infection in mice. Microbiol Immunol 26:359–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1982.tb00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sethi KK, Omata Y, Schneweis KE. 1983. Protection of mice from fatal herpes simplex virus type 1 infection by adoptive transfer of cloned virus-specific and H-2-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Gen Virol 64:443–447. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-64-2-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Staats HF, Oakes JE, Lausch RN. 1991. Anti-glycoprotein D monoclonal antibody protects against herpes simplex virus type 1-induced diseases in mice functionally depleted of selected T-cell subsets or asialo GM1+ cells. J Virol 65:6008–6014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manickan E, Rouse BT. 1995. Roles of different T-cell subsets in control of herpes simplex virus infection determined by using T-cell-deficient mouse-models. J Virol 69:8178–8179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nash AA, Jayasuriya A, Phelan J, Cobbold SP, Waldmann H, Prospero T. 1987. Different roles for L3T4+ and Lyt 2+ T cell subsets in the control of an acute herpes simplex virus infection of the skin and nervous system. J Gen Virol 68:825–833. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-68-3-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Freeman GJ, Boussiotis VA, Anumanthan A, Bernstein GM, Ke XY, Rennert PD, Gray GS, Gribben JG, Nadler LM. 1995. B7-1 and B7-2 do not deliver identical costimulatory signals, since B7-2 but not B7-1 preferentially costimulates the initial production of IL-4. Immunity 2:523–532. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuchroo VK, Das MP, Brown JA, Ranger AM, Zamvil SS, Sobel RA, Weiner HL, Nabavi N, Glimcher LH. 1995. B7-1 and B7-2 costimulatory molecules activate differentially the Th1/Th2 developmental pathways: application to autoimmune disease therapy. Cell 80:707–718. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90349-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nakajima A, Azuma M, Kodera S, Nuriya S, Terashi A, Abe M, Hirose S, Shirai T, Yagita H, Okumura K. 1995. Preferential dependence of autoantibody production in murine lupus on CD86 costimulatory molecule. Eur J Immunol 25:3060–3069. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830251112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lenschow DJ, Ho SC, Sattar H, Rhee L, Gray G, Nabavi N, Herold KC, Bluestone JA. 1995. Differential effects of anti-B7-1 and anti-B7-2 monoclonal antibody treatment on the development of diabetes in the nonobese diabetic mouse. J Exp Med 181:1145–1155. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miller SD, Vanderlugt CL, Lenschow DJ, Pope JG, Karandikar NJ, Dal Canto MC, Bluestone JA. 1995. Blockade of CD28/B7-1 interaction prevents epitope spreading and clinical relapses of murine EAE. Immunity 3:739–745. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lenschow DJ, Zeng Y, Hathcock KS, Zuckerman LA, Freeman G, Thistlethwaite JR, Gray GS, Hodes RJ, Bluestone JA. 1995. Inhibition of transplant rejection following treatment with anti-B7-2 and anti-B7-1 antibodies. Transplantation 60:1171–1178. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199511270-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thompson CB. 1995. Distinct roles for the costimulatory ligands B7-1 and B7-2 in T helper cell differentiation? Cell 81:979–982. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(05)80001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Greenfield EA, Nguyen KA, Kuchroo VK. 1998. CD28/B7 costimulation: a review. Crit Rev Immunol 18:389–418. doi: 10.1615/CritRevImmunol.v18.i5.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Freeman GJ, Gribben JG, Boussiotis VA, Ng JW, Restivo VA Jr, Lombard LA, Gray GS, Nadler LM. 1993. Cloning of B7-2: a CTLA-4 counter-receptor that costimulates human T cell proliferation. Science 262:909–911. doi: 10.1126/science.7694363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lanier LL, O'Fallon S, Somoza C, Phillips JH, Linsley PS, Okumura K, Ito D, Azuma M. 1995. CD80 (B7) and CD86 (B70) provide similar costimulatory signals for T cell proliferation, cytokine production, and generation of CTL. J Immunol 154:97–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jeon S, Rowe AM, Carroll KL, Harvey SAK, Hendricks RL. 2018. PD-L1/B7-H1 inhibits viral clearance by macrophages in HSV-1-infected corneas. J Immunol 200:3711–3719. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schrimpf JE, Tu EM, Wang H, Wong YM, Morrison LA. 2011. B7 costimulation molecules encoded by replication-defective, vhs-deficient HSV-1 improve vaccine-induced protection against corneal disease. PLoS One 6:e22772. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bugeon L, Wong KK, Rankin AM, Hargreaves RE, Dallman MJ. 2006. A negative regulatory role in mouse cardiac transplantation for a splice variant of CD80. Transplantation 82:1334–1341. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000239343.01775.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hill A, Jugovic P, York I, Russ G, Bennink J, Yewdell J, Ploegh H, Johnson D. 1995. Herpes simplex virus turns off the TAP to evade host immunity. Nature 375:411–415. doi: 10.1038/375411a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Goldsmith K, Chen W, Johnson DC, Hendricks RL. 1998. Infected cell protein (ICP)47 enhances herpes simplex virus neurovirulence by blocking the CD8+ T cell response. J Exp Med 187:341–348. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.3.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Heilingloh CS, Muhl-Zurbes P, Steinkasserer A, Kummer M. 2014. Herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP0 induces CD83 degradation in mature dendritic cells independent of its E3 ubiquitin ligase function. J Gen Virol 95:1366–1375. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.062810-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van Lint AL, Murawski MR, Goodbody RE, Severa M, Fitzgerald KA, Finberg RW, Knipe DM, Kurt-Jones EA. 2010. Herpes simplex virus immediate-early ICP0 protein inhibits Toll-like receptor 2-dependent inflammatory responses and NF-κB signaling. J Virol 84:10802–10811. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00063-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bell S, Cranage M, Borysiewicz L, Minson T. 1990. Induction of immunoglobulin G Fc receptors by recombinant vaccinia viruses expressing glycoproteins E and I of herpes simplex virus type 1. J Virol 64:2181–2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Johnson DC, Frame MC, Ligas MW, Cross AM, Stow ND. 1988. Herpes simplex virus immunoglobulin G Fc receptor activity depends on a complex of two viral glycoproteins, gE and gI. J Virol 62:1347–1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Adler R, Glorioso JC, Cossman J, Levine M. 1978. Possible role of Fc receptors on cells infected and transformed by herpesvirus: escape from immune cytolysis. Infect Immun 21:442–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Eisenberg RJ, Ponce de Leon M, Friedman HM, Fries LF, Frank MM, Hastings JC, Cohen GH. 1987. Complement component C3b binds directly to purified glycoprotein C of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2. Microb Pathog 3:423–435. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90012-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Friedman HM, Wang L, Fishman NO, Lambris JD, Eisenberg RJ, Cohen GH, Lubinski J. 1996. Immune evasion properties of herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein gC. J Virol 70:4253–4260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Drolet B, Mott K, Lippa A, Wechsler S, Perng G-C. 2004. Glycoprotein C of herpes simplex virus type 1 is required to cause keratitis at low infectious doses in intact rabbit corneas. Curr Eye Res 29:181–189. doi: 10.1080/02713680490504542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lin X, Lubinski JM, Friedman HM. 2004. Immunization strategies to block the herpes simplex virus type 1 immunoglobulin G Fc receptor. J Virol 78:2562–2571. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.5.2562-2571.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Judson KA, Lubinski JM, Jiang M, Chang Y, Eisenberg RJ, Cohen GH, Friedman HM. 2003. Blocking immune evasion as a novel approach for prevention and treatment of herpes simplex virus infection. J Virol 77:12639–12645. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.23.12639-12645.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mott KR, Underhill D, Wechsler SL, Town T, Ghiasi H. 2009. A role for the JAK-STAT1 pathway in blocking replication of HSV-1 in dendritic cells and macrophages. Virol J 6:56. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ghiasi H, Kaiwar R, Nesburn AB, Slanina S, Wechsler SL. 1994. Expression of seven herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoproteins (gB, gC, gD, gE, gG, gH, and gI): comparative protection against lethal challenge in mice. J Virol 68:2118–2126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cai WZ, Schaffer PA. 1989. Herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP0 plays a critical role in the de novo synthesis of infectious virus following transfection of viral DNA. J Virol 63:4579–4589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.DeLuca NA, Schaffer PA. 1987. Activities of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) ICP4 genes specifying nonsense peptides. Nucleic Acids Res 15:4491–4511. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.11.4491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McCarthy AM, McMahan L, Schaffer PA. 1989. Herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP27 deletion mutants exhibit altered patterns of transcription and are DNA deficient. J Virol 63:18–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bowman JJ, Orlando JS, Davido DJ, Kushnir AS, Schaffer PA. 2009. Transient expression of herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP22 represses viral promoter activity and complements the replication of an ICP22 null virus. J Virol 83:8733–8743. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00810-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tomazin R, Hill AB, Jugovic P, York I, van Endert P, Ploegh HL, Andrews DW, Johnson DC. 1996. Stable binding of the herpes simplex virus ICP47 protein to the peptide binding site of TAP. EMBO J 15:3256–3266. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00690.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Allen SJ, Mott KR, Matsuura Y, Moriishi K, Kousoulas KG, Ghiasi H. 2014. Binding of HSV-1 glycoprotein K (gK) to signal peptide peptidase (SPP) is required for virus infectivity. PLoS One 9:e85360. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Selvakumar A, White PC, Dupont B. 1993. Genomic organization of the mouse B-lymphocyte activation antigen B7. Immunogenetics 38:292–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mott KR, UnderHill D, Wechsler SL, Ghiasi H. 2008. Lymphoid-related CD11c+ CD8a+ dendritic cells are involved in enhancing HSV-1 latency. J Virol 82:9870–9879. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00566-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ghiasi H, Bahri S, Nesburn AB, Wechsler SL. 1995. Protection against herpes simplex virus-induced eye disease after vaccination with seven individually expressed herpes simplex virus 1 glycoproteins. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 36:1352–1360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ghiasi H, Purdy MA, Roy P. 1985. The complete sequence of bluetongue virus serotype 10 segment 3 and its predicted VP3 polypeptide compared with those of BTV serotype 17. Virus Res 3:181–190. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(85)90007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.