Abstract

Objective

HIV-positive children, adolescents, and young adults are at increased risk poor musculoskeletal outcomes. Increased incidence of vitamin D deficiency in youth living with HIV may further adversely affect musculoskeletal health. We investigated the impact of vitamin D supplementation on a range of musculoskeletal outcomes among individuals aged 0–25 years living with HIV.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted using databases: PubMed/Medline, CINAHL, Web of Knowledge, and EMBASE. Interventional randomised control trials, quasi-experimental trials, and previous systematic reviews/meta-analyses were included. Outcomes included: BMD, BMC, fracture incidence, muscle strength, linear growth (height-for-age Z-score [HAZ]), and biochemical/endocrine biomarkers including bone turnover markers.

Results

Of 497 records, 20 studies met inclusion criteria. Thirteen studies were conducted in North America, one in Asia, two in Europe, and four in Sub-Saharan Africa. High-dose vitamin D supplementation regimens (1,000–7,000 IU/day) were successful in achieving serum 25-hydroxyvitamin-D (25OHD) concentrations above study-defined thresholds. No improvements were observed in BMD, BMC, or in muscle power, force and strength; however, improvements in neuromuscular motor skills were demonstrated. HAZ was unaffected by low-dose (200–400 IU/day) supplementation. A single study found positive effects on HAZ with high-dose supplementation (7,000 vs 4,000IU/day).

Conclusions

Measured bone outcomes were unaffected by high-dose vitamin D supplementation, even when target 25OHD measurements were achieved. This may be due to: insufficient sample size, follow-up, intermittent dosing, non-standardised definitions of vitamin D deficiency, or heterogeneity of enrolment criteria pertaining to baseline vitamin D concentration. High-dose vitamin D may improve HAZ and neuromuscular motor skills. Adequately powered trials are needed in settings where HIV burden is greatest.

PROSPERO Number: CRD42016042938.

Introduction

The global scale-up of antiretroviral therapy (ART) has dramatically improved survival of those living with HIV and converted what was once a life-threatening infection into a chronic, treatable condition. HIV management now includes treatment of HIV infection, as well as associated chronic comorbidities, for example increased risk of low bone mineral density (BMD) [1–4]. Low BMD in youth living with HIV has been shown to far exceed those of HIV-negative controls [3,5]. Similarly, multiple observational studies, in both high- and low-middle-income countries (LMIC), have demonstrated vitamin D insufficiency in HIV-positive children, adolescents, and young adults [6–9], with a single study demonstrating increased rates compared to HIV-negative age-matched controls [10].

During childhood and adolescent growth, bones grow in length, width and mineral content until peak bone mass (PBM) is achieved [11]; PBM is a key determinant of future adult osteoporosis and lifetime fracture risk [12–14]. ‘Low bone mass’, defined as a dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) measured BMD Z-score ≤ -2 has been associated with low 25OHD and altered vitamin D metabolism in HIV-positive youths [15,16]. Furthermore, HIV infection increases bone turnover to reduce BMD even when vitamin D concentration is adequate [16]. HIV-associated alterations in vitamin D and bone metabolism are thought to arise from inflammatory and metabolic properties of the HIV infection itself [17–20] and/or side effects of ART [21–27] altering the molecular balance between bone formation and resorption. Intestinal absorption, nutritional intake and/or sun exposure may also be reduced [28–31]. HIV can cause delayed puberty [32,33] with associated reductions in bone mass [34–36] and restricted linear growth [37]. Inadequate dietary vitamin D is associated with growth failure (i.e. height-for-age Z-scores [HAZ] <-2) in HIV-positive children [38]. In sum, direct and indirect effects of HIV on musculoskeletal health are multifactorial and are potentially exacerbated by inadequate vitamin D.

Most current guidelines define vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency as a serum vitamin D value (25OHD) <30 nmol/L (<12 ng/ml) and between 30–50 nmol/L respectively (12–20 ng/ml); however, consensus is lacking and defined thresholds vary between countries and specialty advisory committees [39–41]. Some experts advocate higher values (e.g >75 nmol/L [>30 ng/ml]) in order to acieve maximal suppression of parathyroid hormone (PTH) and to optimise bone matrix formation in light of altered vitamin D metabolism with HIV [42].

Vitamin D supplementation has been shown to improve BMD in a range of paediatric chronic diseases such as epilepsy [43], kidney disease [44] and juvenile idiopathic arthritis [45], and to improve muscle function in HIV-negative adolescent girls [46]. Hence, it has been hypothesised that the beneficial effects of vitamin D supplementation can be reproduced in HIV infection.

Globally, there is an absence of evidence-based guidelines for vitamin D supplementation in youth living with HIV. We aimed to systematically review the current evidence examining the relationships between vitamin D supplementation and a range of musculoskeletal outcomes in children, adolescents, and young adults living with HIV, to guide future strategies to optimise musculoskeletal health.

Methods

Search strategy

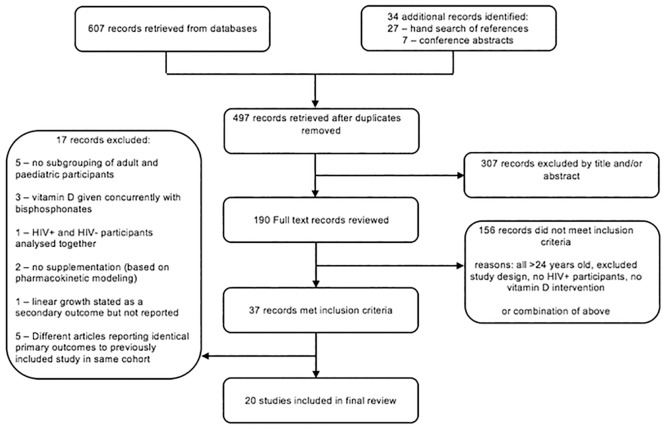

Search strategy followed PRISMA guidance [47] (Fig 1). Articles were restricted to those published in English and French from the year 2000–2017, reflecting the period of ART availability. Articles were not restricted by geographic location. The following databases were searched: PubMed/Medline, EMBASE, CINAHL, and Web of Knowledge, (S1–S4 Tables). A hand search of the references cited for each retrieved article was performed. Furthermore, available conference abstracts, within the past six years, were reviewed from: (i) the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, (ii) International AIDS Society, (iii) Infectious Diseases Society of America ID Week, and (iv) the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research.

Fig 1. PRISMA flow diagram of search results.

Study selection

Interventional trials of oral or parenteral vitamin D with or without calcium were assessed, including randomised control trials (RCT) and quasi-experimental studies (QET) (both controlled and uncontrolled). Controlled QET consisted of pre- and post-intervention studies with vitamin D and non-vitamin D arms, in addition to studies comparing high-dose and standard-dosing regimens (standard-dose defined: ≤800 International Units [IU]/day). Uncontrolled QETs were considered if they utilised either a one group pre- post-intervention design (vitamin D only) or an interrupted-time-series design [48]. Previous systematic reviews were included. To ensure enough time to achieve outcomes, a minimum of six months follow-up after enrolment was required for studies reporting radiological or clinical outcomes and three months for those reporting biochemical/endocrine outcomes. Studies that had at least 10 individuals aged 1 month to 25 years, regardless of the mode of HIV acquisition and HIV treatment status (ART naïve or experienced) were considered. Studies assessing bisphosphonates in conjunction with vitamin D supplementation were excluded.

Eligibility for inclusion was determined independently by two reviewers (JP & CR) using an assessment toolkit with a pre-defined inclusion checklist [49,50].

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were extracted independently using the Cochrane Public Health Group Data Extraction and Assessment Form [50], with risk of bias (ROB) assessed using the Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews and reported independently as high, low, or unclear by both reviewers (JP & CR) [49]. Data on study latitude/geographic location, participant age, gender, seasonality, adherence, dietary vitamin D intake (IU/day), skin colour/sun exposure and method of 25OHD and 1,25OHD quantification were recorded.

Biochemical/endocrine outcomes

Data were extracted for the biologically active variant and the stored form of vitamin D, hydroxylated (1,25OHD) and non-hydroxylated (25OHD) vitamin D respectively, as well as: endocrine/biochemical markers (calcium, phosphate, bone alkaline phosphatase [BAP], PTH, and fibroblast growth factor [FGF]), serum and urine biomarkers of bone turnover (osteocalcin [OC], procollagen type-1 N-terminal propeptide [P1NP], collagen type-1 cross-linked C-telopeptide [CTX], and N-terminal telopeptide [NTX]), and markers of systemic inflammation (CRP, D-dimer, interleukins, tumour necrosis factors, and interferons).

Doses of vitamin D supplementation were standardised into daily doses (IU/day). Definitions of vitamin D deficiency, insufficiency, and sufficiency were extracted for between-study comparison (S5 Table).

Musculoskeletal outcomes (bone, muscle and linear growth)

BMC and BMD measured using the following radiographic techniques were acceptable: DXA, computed tomography (including pQCT and high resolution pQCT), quantitative ultrasound (measured by either speed of sound, broadband ultrasound attenuation, or stiffness index), and/or digital X-ray radiogrammetry. For those not reporting BMD Z-scores, BMD measurements were compared against standardised, age-matched paediatric Z-scores as outlined by the International Society of Clinical Densitometry (ISCD) [51].

Studies assessing muscle function by measuring muscle strength, power, and/or force were considered relevant, as were studies assessing muscle size and mass. Linear growth was reported as HAZ, where SDs and standard error can be computed from Z-score values. HAZ summary statistics by age/sex represent a comparison to WHO reference standards with an expected mean HAZ of zero and SD of one. Z-scores were compared to the WHO Global Database on Child Growth and Malnutrition standard classifications, if not reported by the study authors [52]. Clinical outcomes of incident fractures and prevalent rickets and osteomalacia were extracted.

Adverse events

All adverse effects of vitamin D supplementation were recorded. Hypercalcemia, hypercalciuria, renal calculi, and gastrointestinal upset were specifically screened for as these are recognised complications of cholecalciferol supplementation in healthy populations [53].

Results

Study characteristics

A total of 607 articles were retrieved from database searches, a further 27 from hand searches of references, and 7 conference abstracts. After removal of duplicates, 497 articles were screened by title and abstract. The resulting 190 articles were then reviewed in full, of which 37 studies met inclusion criteria (Fig 1). The final 20 included studies were published between 2009–2017. Thirteen studies were conducted in North America (USA, Canada), two in Europe (France, Italy), four in Sub-Saharan Africa (Botswana, South Africa, Uganda), and one published conference abstract from Thailand. The follow-up time of the studies ranged from three months to two years. All studies used oral Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) except the ongoing Sudjaritruk et al. study which used D2 (ergocalciferol) for supplementation [54]. Four studies supplemented calcium in conjunction with vitamin D [55,56,57,58] whereas three studies utilised a multiple-micronutrient supplement which did not contain calcium [59,60,61]. There was considerable dosing heterogeneity in regimens, ranging from 200–7,000 IU/day. Lower dose regimens (200–400 IU/day) were used primarily in studies measuring HAZ, whereas higher doses (1,000–7,000 IU/day) were used in those measuring biochemical/endocrine and bone/muscle outcomes.

Studies are listed in Tables 1–4. Brown et al. [62] and Rovner et al. [63] published a secondary analyses of muscle and bone outcomes generated by Stallings et al. [64]. Arpadi et al. (2012) published a follow-up study of the same population described by Arpadi et al. (2009), but outcomes differed [55,56]. Havens et al. (2012b & 2014) published two secondary analyses of data reported initially by Havens et al. (2012a) [65–67] and a third study assessing BMD in conjunction with longitudinal biochemical data [68].

Table 1. Characteristics of studies assessing serum biomarkers/endocrine factors in response to cholecalciferol supplementation.

| Study author, year, country | Study design | Population (n) and gender6 | Age1 range and mean (SD) | Mode of HIV acquisition | Intervention2 (mean daily VD dose)3 (n) | Control (n) | Baseline 25OHD (nmol/L)4 and exclusions | Summary of main findings (25OHD nmol/L)4,5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Arpadi et al., 2009, USA[55] |

Double-blind RCT | 56 M: 39.3% |

6–16 years | 100% perinatal |

|

|

Baseline 25OHD in VD+ = 62.2 (22.7) |

|

| Stratified by gender and age | VD+ 10.2(2.9) VD- 10.6 (2.4) |

25OHD <30 nmol/L excluded (n = 5) | ||||||

| Participants on TDF excluded | ||||||||

|

Dougherty et al., 2014, USA [72] |

Double-blind uncontrolled QET (pre- post-intervention experimental trial) | 44 M: 18.7% |

8.3–24.9 years 18.7(4.7) |

43% perinatal 57% horizontal |

|

|

Baseline 25OHD in 4,000 IU/day = 18.6 (11–81.1)9 |

|

| 4,000 IU group 18.4 (4.5) 7,000IU group 19.1 (5) |

Baseline 25OHD in 7,000 IU/day = 56.2 (28.2–83.9)9 | |||||||

| No baseline 25OHD exclusion criteria | ||||||||

|

Eckard et al., 2017, USA [77] |

Double-blind RCT | 102 M: 64% |

8–25 years 20.3 (16.6–22.8)8 |

53% perinatal |

|

|

Baseline 25OHD for all participants = 42.4 (32.4–54.9)8 |

|

| Initially stratified by EFV use | Excluded if baseline 25OHD >75 | |||||||

|

Foissac et al., 2014, France [69] |

Open-label QET (pre- post-pharmacokinetic intervention trial) | 91 M: 51.6% |

3–24 years | Not Reported |

|

|

Baseline 25OHD for all participants– 30 (22.5–42.4)8 |

|

| reported by sex: boys: 14(10–17)8 girls: 15(11–17)8 |

No baseline 25OHD exclusion criteria | |||||||

|

Giacomet et al., 2013, Italy [70] |

Double-blind RCT | 52 NR |

8–26 years | 100% perinatal |

|

|

Baseline 25OHD for VD+ = 37.4 (30–47.4)8 |

|

| VD+ 20 (14–23) 7 VD- 18 (15–23) 8 |

25OHD >74.9 and PTH above normal limits excluded Excluded black ethnicity |

|||||||

|

Havens et al. 2012a, USA & Puerto Rico [66] |

Double-blind RCT | 203 M: 62.6% |

18–24.9 years 20.9(2) |

“predominantly (perinatal)” (% not defined) |

|

|

Baseline 25OHD for all participants = 52.9 (30.7) No baseline 25OHD exclusion criteria |

|

| Havens et al. 2012b [67] | Stratified by TDF vs. “noTDF” then randomised | VD+ 20.9 (2.1) VD- 20.9 (1.9) |

||||||

| Havens et al. 2014 [65] | ||||||||

|

Havens et al., 2017 USA & Puerto Rico [57] |

Double-blind RCT | 214 M: 84% |

16–24 years 22 (21–23)7 |

Not defined Median time since HIV diagnosis = 2 years |

|

|

Baseline 25OHD for all participants = 40.9 (28.5–59.7)8 |

|

| Participants all on TDF containing ART Stratified by sex, age, and race | No baseline 25OHD exclusion criteria | |||||||

|

Kakalia et al., 2011, Canada [73] |

Open-label RCT | 53 M: 45.3% |

3–18 years | 91% perinatal 9% horizontal |

|

|

Baseline 25OHD in 800 IU/day group = 49.9 (22.5) Baseline 25OHD in 1,6000 IU/day group = 42.7 (18.1) |

|

| 800IU group 10.6 (4.4) 1600IU group 10.3 (3.2) VD- 10.7(4.4) |

25OHD <25 nmol/L excluded | |||||||

|

Poowuttikul et al., 2014, USA [76] |

Open-label uncontrolled QET (single-arm pre-post-intervention design) | 160 M: 76.3% |

2–26 years | Not reported |

|

|

23.1% of participants with baseline 25OHD 50–87.4 71.9% of participants had baseline 25OHD <49.9 Only participants with 25OHD <87.5 were supplemented |

|

| 8.1% ≤10 years (n = 13) 45% 11–20 years (n = 72) 26.9% 21–26 years (n = 75) | ||||||||

|

Stallings et al., 2015, USA [64] |

Double-blind RCT | 58 M: 38.9% |

5–24.9 years 20.7(3.7) |

36% perinatal 64% horizontal |

|

|

Baseline 25OHD for all participants = 43.9 (21.7) |

|

| Stratified by mode of HIV acquisition then randomised | VD+ 21.3 (3.3) VD- 20.0 (4.1) |

Participants with 3 consecutive 25OHD <27.5 nmol/L withdrawn | ||||||

|

Steenhoff et al., 2015, Botswana [71] |

Double-blind uncontrolled QET (pre- post-intervention design) | 60 M: 50% |

5–50.9 years10 19.5(11.8) |

68% perinatal 32% horizontal |

|

|

Baseline 25OHD in 7,000 IU/day group = 86.1 (23.7) Baseline 25OHD in 4,000 IU/day group = 91.1(23.2) |

|

| 4,000IU group 19.5 (11.8) 7,000 group 19.5 (12) |

Stratified into 5 age groups then randomised | |||||||

| Preliminary Interim Data (from published abstract) | ||||||||

|

Sudjaritruk et al. 2017 Thailand [54] |

Open-label randomized trial | 166 M: 48% |

10–20 years 16.0 (14.4–17.7) |

100% perinatal Median duration of ART 10 years |

|

“normal-dose”: ergocalciferol/Ca (400IU/1.2 g day) | Baseline 25OHD for all participants = 25.3 (20.7–33.2) |

|

| No baseline 25OHD exclusion criteria | ||||||||

1. Mean age based on group allocation and/or overall age when reported.

2. All oral cholecalciferol.

3. Calculated based on 30 days/month.

4. Means (standard deviation) unless otherwise specified.

5. ng/ml transformed to nmol/L

6. Gender reported as percentage male

7. Bimonthly defined: once every 2 months.

8. Median (interquartile range).

9. 60,000 and 120,000 IU/month groups considered together except in bone turnover marker analysis

10. Age adjusted linear model for paediatric patients

1,25OHD = Serum 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 level; 25OHD = Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 concentration; BAP = Bone Alkaline Phosphatase; Ca = Calcium; CTX = Collagen Type-1 Cross-linked C-telopeptide; FGF23 = Fibroblast Growth Factor-23; NR = Not Reported; OC = Osteocalcin; P1NP = Procollagen Type-1 N-terminal Propeptide; PTH = Parathyroid Hormone; QET = Quasi-Experimental Trial; RCT = Randomized Control Trial; TDF = Tenofovir; VD+ = Vitamin D Intervention Arm; VD- = Control Arm

Table 4. Characteristics of studies assessing linear growth in response to cholecalciferol supplementation.

| Study author, year, country | Study design | Population (n) and gender6 | Age1 range and mean (SD) | Mode of HIV acquisition | Intervention2 (mean daily VD dose)3 (n) | Control (n) | Baseline vitamin D (nmol/L)4 levels and exclusions | Summary of main findings (25OHD nmol/L)4,5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Chhagan et al., 2010, South Africa [61] |

Double-Blind RCT | 317 (HIV-positive n = 25) M: 60.9% |

6–24 months NR |

100% perinatal |

|

Vitamin A (n = 9) Vitamin A and Zinc (n = 11) |

No baseline 25OHD data |

|

| Stratified by HIV-status and maternal exposure then randomised | No baseline 25OHD exclusion criteria | |||||||

|

Mda et al., 2010, South Africa [59] |

Double-Blind RCT | 99 NR |

6–24 months | 100% perinatal |

|

Placebo powder dissolved in water (n = 49) | No baseline 25OHD data |

|

| VD+ 15.1(5.4) VD- 13.6(5.7) |

No baseline 25OHD exclusion criteria Participants on ART excluded |

|||||||

|

Ndeezi et al., 2010, Uganda [60] |

Double-Blind RCT | 847 M: 50.3% |

12–59 months | 100% perinatal |

|

Standard MMS7 containing vitamin D 200 IU/day (6 micronutrients at RDA) (n = 421) | No baseline 25OHD data |

|

| Stratified by ART vs no ART then randomised Treatment group given enhanced MMS for 6 months then standard MMS for remaining 6 months of study |

ART+ VD+ (n = 43) (8.6%)<36months ART+ VD- (n = 42) 38.1%<36months No ART+ VD+ (n = 383) 57.2%<36months No ART+ VD- (n = 379) 59.9%<36months |

No baseline 25OHD exclusion criteria | ||||||

|

Steenhoff et al., 2015, Botswana [71] |

Double-blind uncontrolled QET (pre- post-intervention design) | 60 M: 50% |

5–50.9 years8 19.5 (11.8) |

68% perinatal 32% horizontal |

|

None | Baseline 25OHD in 7,000 IU/day group = 86.1 (23.7) Baseline 25OHD in 4,000 IU/day group = 91.1(23.2) |

|

| 4,000 IU group 19.5 (11.8) 7,000 IU group 19.5 (12) |

Stratified into 5 age groups then randomised |

1. Mean age based on group allocation and/or overall age when reported.

2. All oral cholecalciferol.

3. Calculated based on 30 days/month.

4. Means (standard deviation) unless otherwise specified.

5. ng/ml transformed to nmol/L

6. Gender reported as percentage male

7. Multivitamin did not contain calcium

8. HAZ subcategorized by age (<20 years old; n = 40)

25OHD = Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 concentration; ART = Antiretroviral Therapy; HAZ = Height-for-Age Z-score; MMS = Multiple-micronutrient Supplement; NR = Not Reported; QET = Quasi-Experimental Trial; RCT = Randomized Control Trial; RDA = Recommended Daily Allowance; VD+ = Vitamin D Intervention Arm; VD- = Control Arm

Study participants

Overall, the 20 trials included individuals aged six months to 25 years old. With the exception of one Hepatitis C co-infected individual in the Foissac et al. [69] study, participants had no concomitant acute and/or chronic disease, apart from HIV. There were no patients noted to have concurrent TB. Mean CD4 count, when reported, varied between 587 [66] and 1041 [60], and average CD4% from 27.8% [55] to 35.5% [70]. The majority of participants did not have an AIDS-defining illness, except in the Botswanan trial published by Steenhoff et al., where 57% had CDC category C disease [71] and in the ongoing Thai trial where 50.3% had WHO stage 3 or 4 disease [54]. The percentage of participants on ART was variable, ranging from 10 to 100%. In the study by Mda et al. those on ART were excluded altogether [59]. Low dietary vitamin D intake among participants as compared to the Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommended daily allowance (RDA) was ubiquitous across studies. Similarly, dietary calcium intake was well below the RDA in the four studies to report this [56,57,64,72].

Study outcomes

The outcomes assessed can be broadly classified into four categories, with several studies reporting primary outcomes in more than one of the following categories: 14 studies assessed biochemical/endocrine parameters, most notably serum 25OHD concentration (Table 1), five studies reported bone outcomes (Table 2), two studies described muscle function and structure findings (Table 3), and four studies analysed HAZ (Table 4).

Table 2. Characteristics of included studies assessing bone outcomes in response to cholecalciferol supplementation.

| Study author, year, country | Study design | Population (n) and gender6 | Age1 range and mean (SD) | Mode of HIV acquisition | Intervention2 (mean daily VD dose)3 (n) | Control (n) | Baseline vitamin D (nmol/L)4 levels and exclusions | Summary of main findings (25OHD nmol/L)4,5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Arpadi et al., 2012, USA [56] |

Double-Blind RCT | 59 M: 44.1% |

6–16 years | 100% perinatal |

|

Double placebo (n = 29) | Baseline 25OHD in VD+ = 62.2 (22.7) |

|

| Stratified by gender and age | VD+10.2(2.8) VD- 11.0(2.3) |

25OHD <30 nmol/L excluded (n = 5) Participants on TDF excluded |

||||||

|

Eckard et al., 2017 USA [77] |

Double-Blind RCT | 102 M: 64% |

8–25 years 20.3 (16.6–22.8)8 |

53% perinatal |

|

18,000 IU monthly (= 600 IU/day) (n = 66) | Baseline 25OHD for all participants = 42.4 (32.4–54.9)8 |

|

| Initially stratified by EFV use | Excluded if baseline 25OHD >75 | |||||||

|

Havens et al., 2017 USA & Puerto Rico [57] |

Double-Blind RCT | 214 M: 84% |

16–24 years 22 (21–23)8 |

Not defined Median time since HIV diagnosis = 2 years |

|

Placebo + multivitamin of 400 IU/day + 162 mg Ca (n = 105) | Baseline 25OHD for all participants = 40.9 (28.5–59.7)8 |

|

| Participants all on TDF containing ART Participants stratified by sex, age, and race | No baseline 25OHD exclusion criteria | |||||||

|

Rovner et al., 2017 USA [63] |

Double-Blind RCT | 58 M: 69% |

5–24.9 years 20.9 (3.6) |

35% perinatal |

|

Placebo (n = 28) | Baseline 25OHD for all participants = 45.4 (21.2) |

|

| Participants stratified by age and mode of HIV acquisition | No baseline 25OHD exclusion criteria | |||||||

| Preliminary Interim Data (from published abstract) | ||||||||

|

Sudjaritruk et al. 2017 Thailand [54] |

Open-label randomized trial | 166 M: 48% |

10–20 years 16.0 (14.4–17.7) |

100% perinatal Median duration of ART 10 years |

|

“normal-dose”: ergocalciferol/Ca (400IU/1.2 g day) | Baseline 25OHD for all participants = 25.3 (20.7–33.2) |

|

| Analysis stratified by baseline Low-BMD lumbar spine Z-score | No baseline 25OHD exclusion criteria | |||||||

1. Mean/Median age based on group allocation and/or overall age when reported as such.

2. All oral cholecalciferol unless otherwise stated

3. Calculated based on 30 days/month.

4. Means (standard deviation) unless otherwise specified.

5. ng/ml transformed to nmol/L

6. Gender reported as percentage male

7. Bimonthly defined: once every 2 months.

8. Median (IQR) 8. 60,000 and 120,000 IU/month groups considered together in statistical analysis

25OHD = Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 concentration; Ca = Calcium; EFV = Efavirenz; HBMD = Total Hip Bone Mineral Density;; LSBMC = Lumbar Spine Bone Mineral Content; LSBMD = Lumbar Spine Bone Mineral Density; pQCT = peripheral quantitative computed tomography; RCT = Randomised Control Trial; SBMC = Spinal Bone Mineral Content; SBMD = Spinal Bone Mineral Density; TBBMC = Total Body Bone Mineral Content TBBMD = Total Body Bone Mineral Density; TDF = Tenofovir; VD+ = Vitamin D Intervention Arm; VD- = Control Arm

Table 3. Characteristics of studies assessing muscle outcomes in response to cholecalciferol supplementation.

| Study author, year, country | Study design | Population (n) and gender6 | Age1 range and mean (SD) | Mode of HIV acquisition | Intervention2 (mean daily VD dose)3 (n) | Control (n) | Baseline vitamin D (nmol/L)4 levels and exclusions | Summary of main findings (25OHD nmol/L)4,5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Brown et al., 2015, USA [62] |

Double-Blind RCT | 56 M: 67.9% |

5–24.9 years 20.7(3.8) |

34% perinatal 66% horizontal |

7,000 IU/day (n = 29) | Placebo pill/liquid (n = 27) | Baseline 25OHD for all participants = 43.7 (21.1) |

|

| VD+ 20.0 (4.1) VD- 21.4(3.3) |

2 participants from parent study excluded (Cerebral Palsy) |

|||||||

|

Rovner et al., 2017 USA [63] |

Double-Blind RCT | 58 M: 69% |

5–24.9 years 20.9 (3.6) |

35% perinatal | 7,000 IU/day (n = 30) | Placebo (n = 28) | Baseline 25OHD for all participants = 45.4 (21.2) |

|

| Participants stratified by age and mode of HIV acquisition | No baseline 25OHD exclusion criteria |

1. Mean age based on group allocation and/or overall age when reported.

2. All oral cholecalciferol.

3. Calculated based on 30 days/month.

4. Means (standard deviation) unless otherwise specified.

5. ng/ml transformed to nmol/L

6. Gender reported as percentage male.

RCT = Randomised Control Trial; VD+ = Vitamin D Intervention Arm; VD- = Control Arm.

All studies, except Mda et al. [59], Chhagan et al. [61], and the abstract by Sudjaritruk et al. [54] reported measures of potential harm and/or side-effects of the intervention although none were powered for safety. No significant adverse events directly related to the intervention were observed apart from two cases of renal calculi, although one was remote from the intervention and the other part of the placebo group receiving only 400 IU/day of vitamin D. Minor adverse events, when reported, consisted of transient hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria.

Biochemical/endocrine outcomes

The majority of studies aimed to raise concentrations of 25OHD >75 nmol/L with the goal of maximal PTH suppression (S5 Table). Kakalia et al. demonstrated persistent hyperparathyroidism with serum 25OHD values between 50–75 nmol/L [73]. To achieve a measurement >75 nmol/L, higher supplementation doses (>1,000 IU) than currently recommended were required; though it should be noted that other guidelines such as the Special Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) [40], IOM [74], and European Food Safety Agency [75] guidlines are to achieve population mean levels above the threshold not intended for clinical purposes. Higher mean and trough serum 25OHD values were almost always achieved after supplementation [54,55,57,64,66,70–73,76,77]. Higher mean monthly 25OHD values were seen with higher doses of cholecalciferol [55]. Lower baseline values of 25OHD negatively impacted final serum 25OHD concentrations, and extended the time needed to reach 25OHD >50 nmol/L and 75 nmol/L [66,69]. Without supplementation, dietary intake of cholecalciferol, noted to be between 90–425 IU/day, was insufficient in achieving 25OHD >75 nmol/L. Except for one study [73], responses in both 25OHD and 1,25OHD were equally seen [66,70,72], again with the most marked increase in those with the lowest baseline 1,25OHD measurements [66].

Maximal physiologic PTH suppression, however, was inconsistently observed after cholecalciferol supplementation. Whilst four studies demonstrated decreased serum PTH [54,57,67,72], three did not, despite similar cholecalciferol dosing [64,73,77]. Decreased PTH appeared to be in part dependent on participants’ exposure to tenofovir (TDF). Steenhoff et al. demonstrated no intergroup difference in PTH between 4,000 and 7,000 IU/day, but without a placebo group for comparison [71]. Although less frequently a reported outcome, changes in serum calcium, phosphate and BAP concentrations were found to be largely unaffected after cholecalciferol supplementation [57,67,73]. Interestingly, in one study, changes in PTH and BAP were only observed in the cholecalciferol supplemented group treated with TDF [67].

Changes in markers of bone remodelling (CTX, P1NP, OC) were not seen in two studies where the treatment arm used doses of 2,000 IU/day or less [67,77] but when the treatment dose was increased to 4,000 IU/day a decrease in CTX and P1NP was observed [77]. These findings are similar to those found in the preliminary data by Sudjaritruk et al., however, changes in bone turnover markers were demonstrated in both high- and standard-dose groups without intergroup differences [54]. Increased FGF23 was reported in response to cholecalciferol supplementation, although only in two studies, and increases were only observed in the group receiving TDF-containing ART [57,78].

Musculoskeletal outcomes

In the five studies examining bone outcomes, no significant differences in BMD nor BMC were noted between various high- and standard-doses of cholecalciferol versus placebo, despite significant increases in 25OHD. Notably, as demonstrated by Arpadi et al., 75% who received supplementation did not consistently maintain serum 25OHD >75 nmol/L; 30% had at least one monthly serum 25OHD concentration <50 nmol/L [56]. Preliminary results of a 48-week randomised open-labelled trial assessing BMD after ‘high-dose’ cholecalciferol (3,200 IU/day) versus ‘normal dose’ (400 IU/day), both groups also supplemented with oral calcium, has recently been presented at the 9th International Workshop on HIV paediatrics [54]. Analyses were stratified by the presence of low lumbar spine BMD Z-score at baseline. BMD gains were seen in both ‘high-dose’ and ‘normal-dose’ groups who had low-BMD at baseline. A weak trend was suggested towards greater BMD gains amongst the ‘high-dose’ group; however, full trial data are awaited. Body size adjustment was not consistently considered, despite recommendations for size adjustment by the ISCD [79], which limits the validity of bone outcomes.

In the one study focused on muscle outcomes, cholecalciferol supplementation did not improve muscle power, force, or strength amongst youth undergoing jumping mechanography, ankle and knee isometric/isokinetic testing and grip strength dynamometry, despite substantial cholecalciferol dosing (7,000 IU/day) which achieved significant increases in 25OHD [62]. However, post-hoc multivariate analysis suggested participants with the greatest increases in 25OHD tended to have greater jump power and energy, although it is unclear if this effect was dependent on baseline 25OHD concentration. Interestingly, in one study, cholecalciferol supplementation did have a beneficial effect on neuromuscular motor skills measured using the Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency [80]. This included tests of fine motor precision and integration, dexterity, coordination, balance, and agility. Muscle cross-sectional area was unaffected by cholecalciferol supplementation at the same daily dose in a separate study [57].

Three of four studies examining the effect of cholecalciferol on HAZ provided cholecalciferol as part of a multi-micronutrient supplement and in much lower doses (200–400 IU/day) than the aforementioned studies examining bone and muscle outcomes. No differences in HAZ were observed after 6–18 months on these low-dose regimens [59–61]. Similarly, no differences in HAZ were found in a separate study supplementing 4,000 IU/day to 30 individuals. However, at a much higher dose (7,000 IU/day) this same study found significant differences in HAZ after 12 weeks when compared with 4,000 IU/day [71]. There was again no placebo group for comparison. Furthermore, 32% and 28% of participants, all HIV-positive, in studies by Mda [59] and Steenhoff et al. [71] were reported as ‘already stunted’ (HAZ < -2) at baseline. Those supplemented with cholecalciferol in studies by Ndeezi [60] and Chhagan et al. [61] also had low mean HAZ at enrolment (HAZ -1.27, -0.9 respectively).

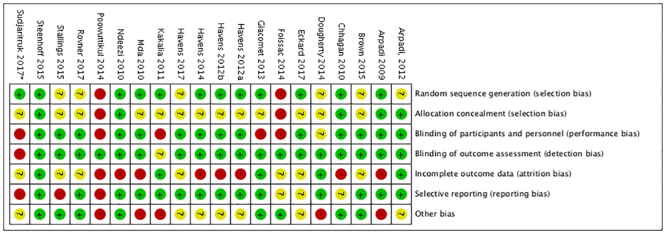

Risk of bias

The majority of studies were deemed of fair to good quality (Fig 2).

Fig 2. Reviewer assessed risk of bias per Cochrane collaboration domain.

High [red], unclear [yellow], and low [green] {Source: created using Review Manager 5.3 [49]}. *Based on avaible data from published abstract, abstract oral presentation, and clinical trials.gov protocol.

Discussion

In response to cholecalciferol supplementation, our review found no clear improvements in BMD, BMC, or in muscle power, force or strength. High-dose cholecalciferol appeared to show some effect on HAZ in a single study. The lack of effect on a broad range of musculoskeletal health outcomes may be due to differences in the definition of vitamin D deficiency used as compared to those in place for the general population (S5 Table) and/or the application of these definitions to the variable baseline 25OHD concentrations (Tables 1–4), which allowed enrollment of individuals with 25OHD concentrations which could in some cases already be deemed sufficient, prior to cholecalciferol supplementation.

The effect of cholecalciferol supplementation on biochemical/endocrine outcomes

The majority of studies aimed to raise 25OHD concentrations >75 nmol/L, intending to supress PTH, although more recent guidelines recommend lower 25OHD concentrations to prevent poor musculoskeletal health in the general population [40,41]. The need for cholecalciferol dosing above that recommended for HIV-negative individuals may be due to reduced intestinal absorption and/or altered vitamin D metabolism, particularly in children and adolescents [31,81]. The omission of those with very low baseline 25OHD biases results against maximal effect; these children and adolescents would largely meet the criteria for rickets/osteomalacia and as such would be expected to benefit most from long-term supplementation. Inclusion of individuals with vitamin D concentrations deemed adequate may have similarly biased results. Alternatively, potentially even higher cholecalciferol doses and thresholds >75 nmol/L for 25OHD may be required. We identified submaximal PTH suppression in 3/7 studies, particularly when lower 25OHD thresholds were used or when 25OHD targets were inconsistently maintained, highlighting the importance of adherence and quality control monitoring in studies. Overall, when assessing for normalisation of biochemical parameters, the studies evaluated seem to favour higher 25OHD targets, e.g. ≥75 nmol/L.

The Endocrine Society Task Force clinical practice guideline remains one of few to contain recommendations addressing vitamin D deficiency in children and young adults living with HIV, although the evidence-base for these recommendations is limited [42]. Our findings do not dispute their recommendation of a standardised maintenance daily dose of cholecalciferol 2–3 times that recommended for age, even in the absence of universal 25OHD screening. This dose may be simplified to 1,500–2,000 IU/day for all paediatric patients, a recommendation which aligns with optimal dose modelling data by Foissac et al. [82]. Higher doses are likely to be required for treatment of documented vitamin D deficiency, and if used, the full safety profile should be substantiated under medical supervision. The Endocrine Society guideline suggests treatment doses of 2,000 IU/day for infants and 4,000 IU/day for children 1–18 years old, which should be accompanied by routine follow-up 25OHD measurements to ensure repletion of biochemical stores. Expert consultation is advocated with higher dosing.

Unfortunately, PTH changes in response to cholecalciferol supplementation were variable. In the five studies addressing bone outcomes, PTH was not measured, not reported, or when reported failed to consistently normalise. Persistently elevated PTH may explain the lack of improvement in BMD/BMC despite increases in 25OHD. Conflicting results in the context of TDF treatment are reported where TDF, by lowering serum 25OHD concentrations, is associated with secondary hyperparathyroidism [83–85]. Havens et al. (2012b) observed a reduction in PTH in those receiving TDF and cholecalciferol. Whilst, in those not receiving TDF, PTH values were unchanged despite increased 25OHD, indicating a possible vitamin D independent effect (67]. Dougherty et al. showed superior 25OHD responses whilst receiving efavirenz (EFV), but without effects on PTH [72]. This finding contrasts with Eckard et al. who demonstrated no differences in 25OHD in those receiving EFV [77]. Likewise, Havens et al. (2012a) showed no PTH response from treatment with either TDF or EFV [66]. Potentially, different ART regimens may influence musculoskeletal outcomes, independent of ARTs’ known impacts on vitamin D metabolism [22,23,86].

Low 25OHD concentrations, with secondary hyperparathyroidism, increase bone turnover (i.e. CTX, P1NP, OC); this is seen in young people with HIV just as it is the wider population [7,87]. Surprisingly, Havens et al. (2012b) failed to corroborate this finding, even with normalisation of PTH in the TDF group [67]. Early treatment with cholecalciferol to prevent subclinical hyperparathyroidism may moderate effects on bone turnover. However, this may require high cholecalciferol dosing. Eckard et al. only demonstrated changes in CTX and P1NP with 4,000 IU/day (although no PTH response was seen) [77].

FGF23, an important regulator of phosphate homeostasis, is secreted by osteocytes in response to 1,25OHD. FGF23 mediated phosphate regulation in HIV-associated vitamin D deficiency remains poorly understood. TDF is associated with phosphaturia which may perpetuate a hypothesised ‘functional vitamin D deficiency’, explained by higher concentrations of vitamin D binding protein (VDBP) reducing free 1,25OHD [21]. Eckard et al. postulated a compensatory decrease in VDBP with EFV after cholecalciferol supplementation [88]. Their findings suggest that TDF and EFV may modify FGF23 response to vitamin D supplementation in adolescents living with HIV by altering vitamin D metabolism, at least in the short term [65]. Further study is needed.

FGF23 increases in renal impairment [89–91], yet only three studies considered renal function in their analysis [67,77,78]. Others excluded patients with renal impairment altogether, or inconsistently measured this at baseline. We further identified heterogeneity in 25OHD assays with five different methods used.

The effect of cholecalciferol supplementation on musculoskeletal outcomes

The absence of any significant effect of cholecalciferol on BMD/BMC in the five retrieved studies may be a real finding or explained by a number of factors. (i) Intermittent dosing may prove insufficient to sustain steady state 25OHD above essential thresholds. Daily, as opposed to monthly/bi-monthly dosing, may be superior but must be balanced against adherence. However, evidence pertaining to optimal dosing schedules remains contentious, particularly as it relates to effects on bone mass, fractures, and falls [92,93] (ii) Arpadi et al.’s exclusion of individuals with the lowest 25OHD measurements may have biased results towards the null, omitting participants who may benefit most from supplementation [56]. (iii) inclusion of individuals with adequate 25OHD concentrations across studies may have equally biased results towards the null, similar to biochemical/endocrine outcomes. (iv) Reported intra-group changes in BMD were not consistently analysed relative to age, changes in body composition (Tanner Staging), and skeletal maturation (particularly height adjustments) [94,95]. Rovner et al. [63] was the only study to explicitly state that such height adjustments were performed whereas Arpadi et al. was the only study to report supplementary analyses of Tanner stage advancement [56]. (v) DXA measurements are size-dependent, hence size correction is crucial, otherwise low BMD/BMC may be explained by reduced height compared to a control population, rather than an actual deficit on bone mass [79]. BMD must be interpreted relative to stature [96,97].

No paediatric studies from LMIC were available. Promisingly, preliminary results by Sudjaritruk et al. represents the first supplementation trial assessing BMD in youth living with HIV outside of the USA; it will be important to see final BMD outcomes correctly size-adjusted and so taking into account growth differences between groups [54]. Furthermore, published data of concurrent changes in biochemical/endocrine markers will be valuable.

Our review highlights a lack of data on muscle size or functional outcomes following cholecalciferol supplementation in HIV-positive youth. Although one study identified increases in neuromuscular motor skills, no effects on muscle power, force or strength were found; perhaps because only 33% achieved 25OH concentrations ≥80 nmol/l. Exploratory post-hoc analysis suggested a responder effect such that participants with increased 25OHD after supplementation did show a positive response in jump power and energy [62]. These neuromuscular improvements are important as poor motor function, evaluated by assessing muscular tone, strength, and muscle volume, have been associated with HIV disease progression [98].

The only study to find an effect of cholecalciferol supplementation on HAZ used high-dose supplementation (7,000 IU/day) and examined linear growth as a secondary outcome [71]. HAZ was the primary outcome in just one, much larger study, but of a much younger, heterogenous population with high attrition rates secondary to death [61]. With the exception of the Steenhoff et al. trial [71], concurrent 25OHD measurements were not evaluated making it difficult to confirm the extent to which 25OHD concentrations improved after supplementation. In addition, high rates of baseline stunting may represent a missed opportunity, as ‘catch-up’ growth may be unattainable even with adequate micronutrient supplementation. It remains unclear at what age intervention may be beneficial. Follow-up time in all studies was ≤18 months, likely insufficient to detect an effect on HAZ, particularly outside of the peri-pubertal growth period. Lastly, studying cholecalciferol as part of a multi-micronutrient supplement may mean effects are confounded by other micronutrients, supporting the need for placebo controlled studies of high-dose vitamin D supplementation alone.

Summary of recommendations for future trials of vitamin D supplementation in young people

Moving forward, studies in LMIC are of particular importance. Trials are needed to establish the effect of vitamin D supplementation on musculoskeletal outcomes before PBM is achieved, targeting the key pubertal stages of maximal growth velocity, when impact may be greatest. Supplementation is needed to avoid secondary hyperparathyroidism which is the primary stimulus for bone turnover [7,99]. Hence, concurrent PTH and 25OHD measurements (at appropriate intervals relative to supplementation doses) are needed in studies measuring BMD/BMC and linear growth. Future studies may also wish to investigate practical adjuncts, such as muscle strength training and weight bearing activity. Fracture incidence should be reported in longitudinal studies, at least as a secondary outcome.

Optimal dosing regimens need to be established. Safety profiles need continued evaluation especially at higher doses and for rare drug-related adverse events, missed by smaller studies. Vitamin D should be supplemented at doses and in regimens that aim to provide sustained 25OHD above pre-defined thresholds. Consensus on threshold 25OHD concentrations defining vitamin D deficiency, insufficiency, and sufficiency would be welcome to standardise studies and permit future meta-analyses. The majority of studies employ a 25OHD target of ≥75 nmol/L as sufficient, with values 50–75 nmol/L considered insufficient and <50 nmol/L deficient. We suggest future studies try not to exclude those with the lowest vitamin D concentrations. Whilst, clinical trials where equipoise is lacking are unethical, for example in cases of symptomatic vitamin D deficiency i.e. rickets, trials in asymptomatic youth who have incidental findings of low 25OHD concentrations which may simply reflect seasonality, can be justified. Where equipoise is lacking, alternative study designs are more appropriate, such as longitudinal study designs evaluating musculoskeletal outcomes before and after cholecalciferol replacement. Studies should also address the long-term effects of supplementation in relation to baseline concentrations, stratifying analysing according to adequacy of baseline 25OHD concentrations.

The combined effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on musculoskeletal outcomes in youth living with HIV remains to be established. Future studies need to consistently report and consider the effects of renal function, latitude, season, ethnicity, and local policies on dietary fortification. Lastly, we recommend standardisation of both DXA measurements to take account of size-adjustment as per the revised 2013 ISCD Pediatric Official Position Guideline and the type of 25OHD assay used [79,100]. Use of alternative modalities in the measurement of bone quality such as pQCT, high resolution pQCT and DXA measured trabecular bone score may prove beneficial and should be investigated in this population [101].

Limitations

Our analysis was limited by the four databases searched and to studies published in English and French. Unfortunately, we were unable to perform a meta-analysis on the available data given the heterogeneity in study designs and populations investigated. This heterogeneity extended to a wide age and geographical range of study particpants, variablity in modes of HIV infection and treatment, and a variety of cholecalciferol supplementation regimes which limits identification of clear patterns in outcomes.

Conclusion

Our systematic review identified few, small studies, with heterogeneous study designs from which we were unable to draw firm conclusions to guide future evidence-based vitamin D supplementation strategies to optimise musculoskeletal health in youth living with HIV. However, we were able to make a series of recommendations which we feel should be considered by all researchers performing much needed further work in this field. Given the successful role out of universal ART and the transition to HIV-associated chronic disease management, there is an urgent need to identify any interventions that may attenuate the musculoskeletal consequences of a lifetime of HIV infection and treatment.

Supporting information

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

1.All values were transformed to nmol/L for standardisation purposes 2.All definitions utilise serum measurements of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3. (ND)Not defined.

(PDF)

From: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097.

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Suzanne Filteau (London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine) who provided clarification regarding data pertaining to stunting in HIV-positive infants.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

CG is funded by Arthritis Research UK (ref 20000). RAF is funded by the Wellcome Trust Trust (206316/Z/17/Z).

References

- 1.Warriner AH, Mugavero M, Overton ET. Bone alterations associated with HIV. Current HIV/AIDS reports. 2014;11(3):233–40. 10.1007/s11904-014-0216-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Puthanakit T, Saksawad R, Bunupuradah T, Wittawatmongkol O, Chuanjaroen T, Ubolyam S, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of low bone mineral density among perinatally HIV-infected Thai adolescents receiving antiretroviral therapy. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2012;61(4):477–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiMeglio LA, Wang J, Siberry GK, Miller TL, Geffner ME, Hazra R, et al. Bone mineral density in children and adolescents with perinatal HIV infection. AIDS (London, England). 2013;27(2):211–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schtscherbyna A, Pinheiro MF, Mendonca LM, Gouveia C, Luiz RR, Machado ES, et al. Factors associated with low bone mineral density in a Brazilian cohort of vertically HIV-infected adolescents. International journal of infectious diseases: IJID: official publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases. 2012;16(12):e872–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mora S, Zamproni I, Beccio S, Bianchi R, Giacomet V, Vigano A. Longitudinal changes of bone mineral density and metabolism in antiretroviral-treated human immunodeficiency virus-infected children. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2004;89(1):24–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sudfeld CR, Duggan C, Aboud S, Kupka R, Manji KP, Kisenge R, et al. Vitamin D status is associated with mortality, morbidity, and growth failure among a prospective cohort of HIV-infected and HIV-exposed Tanzanian infants. The Journal of nutrition. 2015;145(1):121–7. 10.3945/jn.114.201566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sudjaritruk T, Bunupuradah T, Aurpibul L, Kosalaraksa P, Kurniati N, Prasitsuebsai W, et al. Hypovitaminosis D and hyperparathyroidism: Effects on bone turnover and bone mineral density among perinatally HIV-infected adolescents. AIDS (London, England). 2016;30(7):1059–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atkinson Sea. Vitamin D deficiency in children with perinatally acquired HIV-1 infection living in th eUK. 2nd joint Conference of BHIVA with BASHH: poster abstract P1592010.

- 9.Chokephaibulkit K, Saksawad R, Bunupuradah T, Rungmaitree S, Phongsamart W, Lapphra K, et al. Prevalence of vitamin d deficiency among perinatally HIV-infected thai adolescents receiving antiretroviral therapy. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2013;32(11):1237–9. 10.1097/INF.0b013e31829e7a5c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutstein R, Downes A, Zemel B, Schall J, Stallings V. Vitamin D status in children and young adults with perinatally acquired HIV infection. Clinical nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2011;30(5):624–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loud KJ, Gordon CM. Adolescent bone health. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2006;160(10):1026–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hernandez CJ, Beaupre GS, Carter DR. A theoretical analysis of the relative influences of peak BMD, age-related bone loss and menopause on the development of osteoporosis. Osteoporosis international: a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2003;14(10):843–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zemel BS. Human biology at the interface of paediatrics: measuring bone mineral accretion during childhood. Ann Hum Biol. 2012;39(5):402–11. 10.3109/03014460.2012.704071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marshall D, Johnell O, Wedel H. Meta-analysis of how well measures of bone mineral density predict occurrence of osteoporotic fractures. BMJ. 1996;312(7041):1254–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobson DL, Stephensen CB, Miller TL, Patel K, Chen JS, Van Dyke RB, et al. Associations of low Vitamin D and elevated parathyroid hormone concentrations with bone mineral density in perinatally HIV-infected children. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2017;76(1):33–42. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sudjaritruk T, Bunupuradah T, Aurpibul L, Kosalaraksa P, Kurniati N, Prasitsuebsai W, et al. Hypovitaminosis D and hyperparathyroidism: effects on bone turnover and bone mineral density among perinatally HIV-infected adolescents. AIDS (London, England). 2016;30(7):1059–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fakruddin JM, Laurence J. HIV envelope gp120-mediated regulation of osteoclastogenesis via receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand (RANKL) secretion and its modulation by certain HIV protease inhibitors through interferon-gamma/RANKL cross-talk. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278(48):48251–8. 10.1074/jbc.M304676200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fakruddin JM, Laurence J. HIV-1 Vpr enhances production of receptor of activated NF-kappaB ligand (RANKL) via potentiation of glucocorticoid receptor activity. Archives of virology. 2005;150(1):67–78. 10.1007/s00705-004-0395-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cotter EJ, Malizia AP, Chew N, Powderly WG, Doran PP. HIV proteins regulate bone marker secretion and transcription factor activity in cultured human osteoblasts with consequent potential implications for osteoblast function and development. AIDS research and human retroviruses. 2007;23(12):1521–30. 10.1089/aid.2007.0112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gazzola L, Bellistri GM, Tincati C, Ierardi V, Savoldi A, Del Sole A, et al. Association between peripheral T-Lymphocyte activation and impaired bone mineral density in HIV-infected patients. Journal of translational medicine. 2013;11:51 10.1186/1479-5876-11-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Havens PL, Kiser JJ, Stephensen CB, Hazra R, Flynn PM, Wilson CM, et al. Association of higher plasma vitamin D binding protein and lower free calcitriol levels with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate use and plasma and intracellular tenofovir pharmacokinetics: cause of a functional vitamin D deficiency? Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2013;57(11):5619–28. 10.1128/AAC.01096-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hariparsad N, Nallani SC, Sane RS, Buckley DJ, Buckley AR, Desai PB. Induction of CYP3A4 by efavirenz in primary human hepatocytes: comparison with rifampin and phenobarbital. Journal of clinical pharmacology. 2004;44(11):1273–81. 10.1177/0091270004269142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown TT, McComsey GA. Association between initiation of antiretroviral therapy with efavirenz and decreases in 25-hydroxyvitamin D. Antiviral therapy. 2010;15(3):425–9. 10.3851/IMP1502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orkin C, Wohl DA, Williams A, Deckx H. Vitamin D deficiency in HIV: a shadow on long-term management? AIDS reviews. 2014;16(2):59–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cozzolino M, Vidal M, Arcidiacono MV, Tebas P, Yarasheski KE, Dusso AS. HIV-protease inhibitors impair vitamin D bioactivation to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. AIDS (London, England). 2003;17(4):513–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ellfolk M, Norlin M, Gyllensten K, Wikvall K. Regulation of human vitamin D(3) 25-hydroxylases in dermal fibroblasts and prostate cancer LNCaP cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75(6):1392–9. 10.1124/mol.108.053660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norlin M, Lundqvist J, Ellfolk M, Hellstrom Pigg M, Gustafsson J, Wikvall K. Drug-Mediated Gene Regulation of Vitamin D3 Metabolism in Primary Human Dermal Fibroblasts. Basic & clinical pharmacology & toxicology. 2017;120(1):59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coussens AK, Naude CE, Goliath R, Chaplin G, Wilkinson RJ, Jablonski NG. High-dose vitamin D-3 reduces deficiency caused by low UVB exposure and limits HIV-1 replication in urban Southern Africans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112(26):8052–7. 10.1073/pnas.1500909112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Etminani-Esfahani M, Khalili H, Soleimani N, Jafari S, Abdollahi A, Khazaeipour Z, et al. Serum vitamin D concentration and potential risk factors for its deficiency in HIV positive individuals. Current HIV research. 2012;10(2):165–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Isaac R, Paul B, Geethanajali FS, Kang G, Wanke C. Role of intestinal dysfunction in the nutritional compromise seen in human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in rural India. Tropical doctor. 2017;47(1):44–8. 10.1177/0049475515626338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carroccio A, Fontana M, Spagnuolo MI, Zuin G, Montalto G, Canani RB, et al. Pancreatic dysfunction and its association with fat malabsorption in HIV infected children. Gut. 1998;43(4):558–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mothi SN, Swamy VH, Lala MM, Karpagam S, Gangakhedkar RR. Adolescents living with HIV in India—the clock is ticking. Indian journal of pediatrics. 2012;79(12):1642–7. 10.1007/s12098-012-0902-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams PL, Abzug MJ, Jacobson DL, Wang J, Van Dyke RB, Hazra R, et al. Pubertal onset in children with perinatal HIV infection in the era of combination antiretroviral treatment. AIDS (London, England). 2013;27(12):1959–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chevalley T, Bonjour JP, Ferrari S, Rizzoli R. Deleterious effect of late menarche on distal tibia microstructure in healthy 20-year-old and premenopausal middle-aged women. Journal of bone and mineral research: the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2009;24(1):144–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Finkelstein JS, Klibanski A, Neer RM. A longitudinal evaluation of bone mineral density in adult men with histories of delayed puberty. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1996;81(3):1152–5. 10.1210/jcem.81.3.8772591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Martino M, Tovo PA, Galli L, Gabiano C, Chiarelli F, Zappa M, et al. Puberty in perinatal HIV-1 infection: a multicentre longitudinal study of 212 children. Aids. 2001;15(12):1527–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Majaliwa ES, Mohn A, Chiarelli F. Growth and puberty in children with HIV infection. Journal of endocrinological investigation. 2009;32(1):85–90. 10.1007/BF03345686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Modlin CE, Naburi H, Hendricks KM, Lyatuu G, Kimaro J, Adams LV, et al. Nutritional Deficiencies and Food Insecurity Among HIV-infected Children in Tanzania. International journal of MCH and AIDS. 2014;2(2):220–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aspray TJ, Bowring C, Fraser W, Gittoes N, Javaid MK, Macdonald H, et al. National Osteoporosis Society vitamin D guideline summary. Age and ageing. 2014;43(5):592–5. 10.1093/ageing/afu093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Special Advisory Committee On Nutrition. Vitamin D and Health UK: 2016.

- 41.Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, Aloia JF, Brannon PM, Clinton SK, et al. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2011;96(1):53–8. 10.1210/jc.2010-2704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Gordon CM, Hanley DA, Heaney RP, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: An endocrine society clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2011;96(7):1911–30. 10.1210/jc.2011-0385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jekovec-Vrhovsek M, Kocijancic A, Prezelj J. Effect of vitamin D and calcium on bone mineral density in children with CP and epilepsy in full-time care. Developmental medicine and child neurology. 2000;42(6):403–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bak M, Serdaroglu E, Guclu R. Prophylactic calcium and vitamin D treatments in steroid-treated children with nephrotic syndrome. Pediatric nephrology (Berlin, Germany). 2006;21(3):350–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lovell DJ, Glass D, Ranz J, Kramer S, Huang B, Sierra RI, et al. A randomized controlled trial of calcium supplementation to increase bone mineral density in children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(7):2235–42. 10.1002/art.21956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ward KA, Das G, Roberts SA, Berry JL, Adams JE, Rawer R, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of vitamin D supplementation upon musculoskeletal health in postmenarchal females. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2010;95(10):4643–51. 10.1210/jc.2009-2725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2009;339:b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shadish W, Cook T., Campbell D., Experimental and Quasi-experimental designs for generalized casual inference: Houghton Mifflin; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 49.The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager 5.3. 2016.

- 50.The Cochrane Public Health Group. Data Extraction and Assessment Template 2011.

- 51.Skeletal health Assessment In Children from Infancy to Adolescence [Internet]. 2013. http://www.iscd.org/official-positions/2013-iscd-official-positions-pediatric/.

- 52.Onis M BM. WHO Global Database on Child Growth and Malnutrition Geneva: 1997.

- 53.Gallagher JC, Smith LM, Yalamanchili V. Incidence of hypercalciuria and hypercalcemia during vitamin D and calcium supplementation in older women. Menopause (New York, NY). 2014;21(11):1173–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sudjaritruk T, Aurpibul L, Bunupuradah T, Kanjanavanit S, Chotecharoentanan T, Taejaroenkul S, et al. Impacts of vitamin D and calcium supplementation on bone mineral density among perinatally HIV-infected adolescents: a 48-week randomized clinical trial. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2017;20:8–9. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arpadi SM, McMahon D, Abrams EJ, Bamji M, Purswani M, Engelson ES, et al. Effect of bimonthly supplementation with oral cholecalciferol on serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations in HIV-infected children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):e121–6. 10.1542/peds.2008-0176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arpadi SM, McMahon DJ, Abrams EJ, Bamji M, Purswani M, Engelson ES, et al. Effect of supplementation with cholecalciferol and calcium on 2-y bone mass accrual in HIV-infected children and adolescents: a randomized clinical trial. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2012;95(3):678–85. 10.3945/ajcn.111.024786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Havens PL, Stephensen CB, Van Loan MD, Schuster GU, Woodhouse LR, Flynn PM, et al. Vitamin D3 Supplementation Increases Spine Bone Mineral Density in Adolescents and Young Adults with HIV Infection Being Treated with Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sudjaritruk T, Bunupuradah T, Aurpibul L, Kosalaraksa P, Kurniati N, Prasitsuebsai W, et al. Hypovitaminosis D and hyperparathyroidism: effects on bone turnover and bone mineral density among perinatally HIV-infected adolescents. AIDS (London, England). 2016;30(7):1059–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mda S, van Raaij JMA, MacIntyre UE, de Villiers FPR, Kok FJ. Improved appetite after multi-micronutrient supplementation for six months in HIV-infected South African children. Appetite. 2010;54(1):150–5. 10.1016/j.appet.2009.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ndeezi G, Tylleskar T, Ndugwa CM, Tumwine JK. Effect of multiple micronutrient supplementation on survival of HIV-infected children in Uganda: a randomized, controlled trial. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2010;13:18 10.1186/1758-2652-13-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chhagan MK, Van den Broeck J, Luabeya KK, Mpontshane N, Tomkins A, Bennish ML. Effect on longitudinal growth and anemia of zinc or multiple micronutrients added to vitamin A: a randomized controlled trial in children aged 6–24 months. BMC public health. 2010;10:145 10.1186/1471-2458-10-145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brown JC, Schall JI, Rutstein RM, Leonard MB, Zemel BS, Stallings VA. The impact of vitamin D3 supplementation on muscle function among HIV-infected children and young adults: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of musculoskeletal & neuronal interactions. 2015;15(2):145–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rovner AJ, Stallings VA, Rutstein R, Schall JI, Leonard MB, Zemel BS. Effect of high-dose cholecalciferol (vitamin D-3) on bone and body composition in children and young adults with HIV infection: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Osteoporosis International. 2017;28(1):201–9. 10.1007/s00198-016-3826-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stallings VA, Schall JI, Hediger ML, Zemel BS, Tuluc F, Dougherty KA, et al. High-dose Vitamin D-3 Supplementation in Children and Young Adults with HIV A Randomized, Placebo-controlled Trial. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2015;34(2):E32–E40. 10.1097/INF.0000000000000483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Havens PL, Hazra R, Stephensen CB, Kiser JJ, Flynn PM, Wilson CM, et al. Vitamin D3 supplementation increases fibroblast growth factor-23 in HIV-infected youths treated with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. Antiviral therapy. 2014;19(6):613–8. 10.3851/IMP2755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Havens PL, Mulligan K, Hazra R, Flynn P, Rutledge B, Van Loan MD, et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D response to vitamin D3 supplementation 50,000 IU monthly in youth with HIV-1 infection. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2012;97(11):4004–13. 10.1210/jc.2012-2600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Havens PL, Stephensen CB, Hazra R, Flynn PM, Wilson CM, Rutledge B, et al. Vitamin D3 decreases parathyroid hormone in HIV-infected youth being treated with tenofovir: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2012;54(7):1013–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Havens PL, Stephensen CB, Van Loan MD, Schuster GU, Woodhouse LR, Flynn PM, et al. Decline in bone mass with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine is associated with hormonal changes in the absence of renal impairment when used by HIV-uninfected adolescent boys and young men for HIV preexposure prophylaxis. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2017;64(3):317–25. 10.1093/cid/ciw765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Foissac F, Meyzer C, Frange P, Chappuy H, Benaboud S, Bouazza N, et al. Determination of optimal vitamin D3 dosing regimens in HIV-infected paediatric patients using a population pharmacokinetic approach. British journal of clinical pharmacology. 2014;78(5):1113–21. 10.1111/bcp.12433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Giacomet V, Vigano A, Manfredini V, Cerini C, Bedogni G, Mora S, et al. Cholecalciferol supplementation in HIV-infected youth with vitamin D insufficiency: effects on vitamin D status and T-cell phenotype: a randomized controlled trial. HIV clinical trials. 2013;14(2):51–60. 10.1310/hct1402-51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Steenhoff AP, Schall JI, Samuel J, Seme B, Marape M, Ratshaa B, et al. Vitamin D(3)supplementation in Batswana children and adults with HIV: a pilot double blind randomized controlled trial. PloS one. 2015;10(2):e0117123 10.1371/journal.pone.0117123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dougherty KA, Schall JI, Zemel BS, Tuluc F, Hou X, Rutstein RM, et al. Safety and Efficacy of High-Dose Daily Vitamin D3 Supplementation in Children and Young Adults Infected With Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. 2014;3(4):294–303. 10.1093/jpids/piu012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kakalia S, Sochett EB, Stephens D, Assor E, Read SE, Bitnun A. Vitamin D supplementation and CD4 count in children infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Journal of Pediatrics. 2011;159(6):951–7. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Institute of Medicine Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D, Calcium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health In: Ross AC, Taylor CL, Yaktine AL, Del Valle HB, editors. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US) National Academy of Sciences.; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.European Food Safety Agency. Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for Vitamin D. EFSA Journal 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Poowuttikul P, Thomas R, Hart B, Secord E. Vitamin D insufficiency/deficiency in HIV-infected inner city youth. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care. 2014;13(5):438–42. 10.1177/2325957413495566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Eckard AR, O’Riordan MA, Rosebush JC, Ruff JH, Chahroudi A, Labbato D, et al. Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation on Bone Mineral Density and Bone Markers in HIV-Infected Youth. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2017;76(5):539–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Havens PL, Mulligan K, Hazra R, Van Loan MD, Rutledge BN, Bethel J, et al. Increase in fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) in response to vitamin D3 supplementation in HIV-infected adolescents and young adults on tenofovir-containing combination antiretroviral therapy (cART): Adolescent Trials Network (ATN) study 063. Antiviral therapy. 2012;17:A7–A8. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Crabtree NJ, Arabi A, Bachrach LK, Fewtrell M, El-Hajj Fuleihan G, Kecskemethy HH, et al. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry interpretation and reporting in children and adolescents: the revised 2013 ISCD Pediatric Official Positions. J Clin Densitom. 2014;17(2):225–42. 10.1016/j.jocd.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bruininks R. Bruininks-Oseretsky test of motor proficiency. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ansemant T, Mahy S, Piroth C, Ornetti P, Ewing S, Guilland JC, et al. Severe hypovitaminosis D correlates with increased inflammatory markers in HIV infected patients. BMC infectious diseases. 2013;13:7 10.1186/1471-2334-13-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Foissac F, Meyzer C, Frange P, Chappuy H, Benaboud S, Bouazza N, et al. Determination of optimal vitamin D3 dosing regimens in HIV-infected paediatric patients using a population pharmacokinetic approach. British journal of clinical pharmacology. 2014;78(5):1113–21. 10.1111/bcp.12433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Samarawickrama A, Jose S, Sabin C, Walker-Bone K, Fisher M, Gilleece Y. No association between vitamin D deficiency and parathyroid hormone, bone density and bone turnover in a large cohort of HIV-infected men on tenofovir. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2014;17(4 Suppl 3):19568 10.7448/IAS.17.4.19568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pocaterra D, Carenzi L, Ricci E, Minisci D, Schiavini M, Meraviglia P, et al. Secondary hyperparathyroidism in HIV patients: is there any responsibility of highly active antiretroviral therapy? AIDS (London, England). 2011;25(11):1430–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lerma E, Molas ME, Montero MM, Guelar A, Gonzalez A, Villar J, et al. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Vitamin D Deficiency and Hyperparathyroidism in HIV-Infected Patients Treated in Barcelona. Isrn aids. 2012;2012:485307 10.5402/2012/485307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Havens PL, Kiser JJ, Stephensen CB, Hazra R, Flynn PM, Wilson CM, et al. Association of Higher Plasma Vitamin D Binding Protein and Lower Free Calcitriol Levels with Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate Use and Plasma and Intracellular Tenofovir Pharmacokinetics: Cause of a Functional Vitamin D Deficiency? Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2013;57(11):5619–28. 10.1128/AAC.01096-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kwan CK, Eckhardt B, Baghdadi J, Aberg JA. Hyperparathyroidism and Complications Associated with Vitamin D Deficiency in HIV-Infected Adults in New York City, New York. AIDS research and human retroviruses. 2012;28(9):825–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Eckard AR, Thierry-Palmer M, Silvestrov N, Rosebush JC, O’Riordan MA, Daniels JE, et al. Effects of cholecalciferol supplementation on serum and urinary vitamin D metabolites and binding protein in HIV-infected youth. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology. 2017;168:38–48. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2017.01.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liu D, Alvarez-Elias AC, Wile B, Belostotsky V, Filler G. Deviations from the expected relationship between serum FGF23 and other markers in children with CKD: a cross-sectional study. BMC nephrology. 2017;18(1):204 10.1186/s12882-017-0623-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Portale AA, Wolf M, Juppner H, Messinger S, Kumar J, Wesseling-Perry K, et al. Disordered FGF23 and mineral metabolism in children with CKD. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2014;9(2):344–53. 10.2215/CJN.05840513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wesseling-Perry K, Salusky IB. Chronic kidney disease: mineral and bone disorder in children. Seminars in nephrology. 2013;33(2):169–79. 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2012.12.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bolland MJ, Grey A, Reid IR. Differences in overlapping meta-analyses of vitamin D supplements and falls. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2014;99(11):4265–72. 10.1210/jc.2014-2562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Reid IR. Vitamin D Effect on Bone Mineral Density and Fractures. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2017;46(4):935–45. 10.1016/j.ecl.2017.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wren TA, Kalkwarf HJ, Zemel BS, Lappe JM, Oberfield S, Shepherd JA, et al. Longitudinal tracking of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry bone measures over 6 years in children and adolescents: persistence of low bone mass to maturity. The Journal of pediatrics. 2014;164(6):1280–5.e2. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.12.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Burnham JM, Shults J, Semeao E, Foster B, Zemel BS, Stallings VA, et al. Whole body BMC in pediatric Crohn disease: independent effects of altered growth, maturation, and body composition. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(12):1961–8. 10.1359/JBMR.040908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hangartner TN, Short DF, Eldar-Geva T, Hirsch HJ, Tiomkin M, Zimran A, et al. Anthropometric adjustments are helpful in the interpretation of BMD and BMC Z-scores of pediatric patients with Prader-Willi syndrome. Osteoporosis international: a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA. 2016;27(12):3457–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kelly A, Schall JI, Stallings VA, Zemel BS. Deficits in bone mineral content in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis are related to height deficits. J Clin Densitom. 2008;11(4):581–9. 10.1016/j.jocd.2008.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Erlandson KM, Allshouse AA, Jankowski CM, MaWhinney S, Kohrt WM, Campbell TB. Functional impairment is associated with low bone and muscle mass among persons aging with HIV infection. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2013;63(2):209–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Harris SS, Soteriades E, Dawson-Hughes B. Secondary hyperparathyroidism and bone turnover in elderly blacks and whites. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2001;86(8):3801–4. 10.1210/jcem.86.8.7783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]