Introduction

Currarino triad (syndrome) is an extremely rare condition, with an incidence of approximately 1 in 100,000,1 and only about 300 cases reported worldwide so far.2 It is a type of caudal regression syndrome in association with anorectal malformation (ARM), characterized by a triad of presacral mass, sacrococcygeal bone defect, and ARM.3 In view of rarity of this condition, we report an infant, who presented with progressively worsening constipation and was detected to have a complete form of Currarino triad.

Clinical and imaging findings

A 7-month-old female infant patient was brought with history of progressively worsening constipation since 3 months of age. There was no history of excessive crying, intermittent loose stools, fever, lethargy, or excessive sleepiness. There was no significant family history and the anthropometry, general examination, and systemic examination were noncontributory. Examination of the perineum revealed anteriorly displaced anus with a small mass protruding from the posterior aspect (Fig. 1). Digital rectal examination revealed that the mass was partially obliterating anal canal, and there was a palpable bony defect felt in addition, over the sacrum. MRI pelvis revealed a lobulated fat intensity mass with few cysts within, in the presacral region, which was extending posteriorly into the spinal canal (Fig. 2A and B). CT scan pelvis showed a similar soft tissue mass with no calcifications (Fig. 2C). The bony sacrum was ill-formed (scimitar sacrum) and coccygeal elements were not visualized (Fig. 3). Tumor markers, alpha feto protein (AFP) and beta human chorionic gonadotrophin (HCG), both were in normal range. In view of a presacral mass, ARM, and sacral anomaly, a diagnosis of Currarino triad was considered. She underwent three-stage repair involving diverting divided sigmoidostomy followed by definitive repair and then stoma closure. The definitive repair was through a posterior sagittal anorectoplasty (PSARP) approach in which tumor was dissected out along with exploration of sacral canal to remove the intrasacral extension and detethering of cord (Fig. 4). Anoplasty was done after excision to reposition anal canal at the anatomical location. Post-op recovery was uneventful and after the restoration of bowel continuity, the bowel habits became normal with good continence. Histopathological examination later revealed the presacral mass to be a mature teratoma.

Fig. 1.

Anteriorly displaced anus with small mass protruding from posterior aspect.

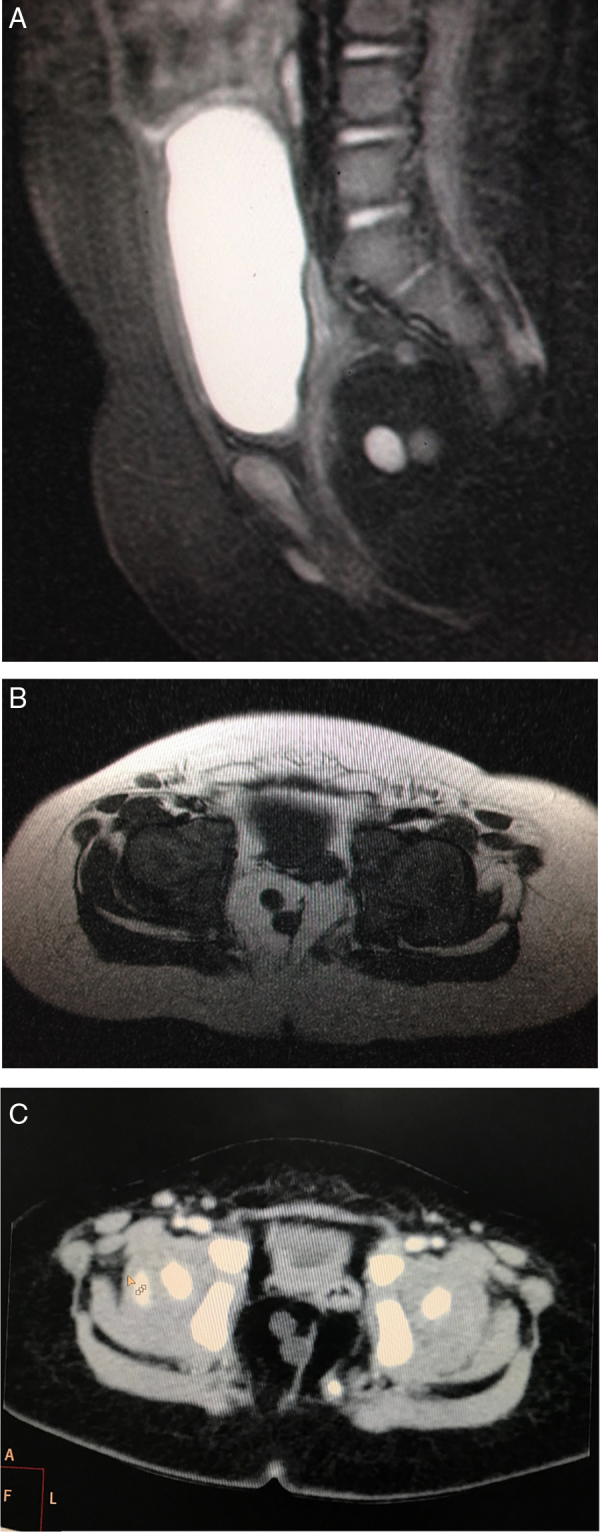

Fig. 2.

(A, B) Sagittal T2W Fat Sat and axial T1W and image of pelvis showing lobulated fat intensity mass with small cystic areas within, in the presacral region which was extending posteriorly into the spinal canal. (C) CT scan pelvis showing fat attenuating mass in the presacral region displacing the rectum anterolaterally to the left. There were no calcific densities within the mass.

Fig. 3.

Reconstructed computed tomography (CT) of spine showing abnormal sacrum (hemisacrum) with missing coccygeal segments.

Fig. 4.

Repair through a posterior sagittal anorectoplasty (PSARP).

Discussion

Currarino triad is a type of persistent neurenteric malformation consisting of ARM, sacral bone abnormality, and presacral mass. The patient had anterior ectopic anus (recto perineal fistula) which is the most frequent type of rectal anomaly in Currarino syndrome (CS).4 Other malformations reported in literature are imperforate anus, rectourethral fistula, rectovaginal fistula, anal atresia and anorectal stenosis. Presacral mass in our patient was a mature teratoma. There are reports in literature of anterior meningocele, malignant teratoma, enteric cyst, lipoma, dermoid cyst, or in any combination of such masses as presacral mass. Similarly, sacral bone abnormalities reported are agenesis of sacrum and coccyx, sickle-shaped sacrum, hemisacrum, etc.3, 4, 5, 6 Malformations of Currarino triad are thought to arise from a failure of dorsoventral separation of the caudal cell mass from the hindgut endoderm during late gastrulation.7 Both sporadic cases and familial predisposition with autosomal inheritance are known to occur.2 Earlier in autosomal dominant hereditary pattern of inheritance, a responsible gene was mapped at chromosome 7 (7q36 region).8 This linkage has recently been refined to a homeobox gene, HLXB9, as the major gene for inherited sacral agenesis.9

This triad may remain asymptomatic in up to a third of affected children. Common symptoms associated with this syndrome are constipation, retention of urine, incontinence of bowel, sacral anesthesia, paresthesia of lower extremities, and obstruction of bowel.10 In our patient, constipation was the presenting feature which is the most common presentation of this syndrome as described in literature. In a patient with suspect ARM, the various radiological investigations necessary to evaluate the complex nature of this triad include radiograph abdomen and spine, ultrasound of abdomen and pelvis, and MRI of abdomen, pelvis, and spine. The excision and repair can be done in a single sitting or as a staged procedure. Staged surgery is generally performed initially to divert the colon and avoid contamination during spinal canal exploration.11 Our patient underwent PSARP with diverting colostomy along with removal of presacral mass, which is generally considered a safe and satisfactory method of definitive surgery. In Currarino triad with anterior meningoceles, repair of the meningocele should be performed before correction of ARM, as there is risk of meningitis that can occur if surgeries are done simultaneously.6 The possibility of Hirschprung's disease as an association should be kept in mind and distal colonic segment should be subjected to histopathological assessment, else it can lead to persistence of constipation.12 In case of late presentations with established tethered cord, neurological outcome of surgical resection is often not optimal.

To conclude, we have reported a case of Currarino triad in an infant, presenting with chronic constipation. The aim of reporting this case is to sensitize the readers of a relatively rare syndrome that should be kept in mind while evaluating a case of ARM or constipation.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Orphanet Report Series . 2016. Prevalence of Rare Diseases: Bibliographic Data. No. 1. http://www.orpha.net/orphacom/cahiers/docs/GB/Prevalence_of_rare_diseases_by_alphabetical_list.pdf Accessed 04.04.17. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarsu S.B., Parmaksiz M.E., Cabalar E., Karapur A., Kaya C. A very rare cause of anal atresia: Currarino syndrome. J Clin Med Res. 2016;8(5):420–423. doi: 10.14740/jocmr2505w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Currarino G., Colon D., Votteler T. Triad of anorectal, sacral, and presacral anomalies. Am J Radiol. 1981;137:395–398. doi: 10.2214/ajr.137.2.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martucciello G., Torre M., Belloni E. Currarino syndrome: proposal of a diagnostic and therapeutic protocol. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39(9):1305–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.AbouZeid A.A., Mohammad S.A., Abolfotoh M., Radwan A.B., Ismail M.M., Hassan T.A. The Currarino triad: what pediatric surgeons need to know. J Pediatr Surg. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.12.010. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee S.C., Chun Y.S., Jung S.E., Park K.W., Kim W.K. Currarino triad: anorectal malformation, sacral bony abnormality, and presacral mass – a review of 11 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1997 Jan;32(1):58–61. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(97)90094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dias M.S., Azizkhan R.G. A novel embryogenetic mechanism for Currarino's triad: inadequate dorsoventral separation of the caudal eminence from hindgut endoderm. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1998;28:223–229. doi: 10.1159/000028655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lynch S.A., Bond P.M., Copp A.J. A gene for autosomal dominant sacral agenesis maps to the holoprosencephaly region at 7q36. Nat Genet. 1995;11:93–95. doi: 10.1038/ng0995-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross A.J., Ruiz-Perez V., Wang Y. A homeobox gene, HLXB9, is the major locus for dominantly inherited sacral agenesis. Nat Genet. 1998;20:358–361. doi: 10.1038/3828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arora P., Purai N., Rajpurkar M., Kamat D. A missed case of Currarino syndrome. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2010;49(2):183–185. doi: 10.1177/0009922809350219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee J.K., Towbin A.J. Currarino syndrome and the effect of a large anterior sacral meningocele on colostogram in an anorectal malformation. J Radiol Case Rep. 2016;10(6):16–21. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v10i6.2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furuta S., Sato H., Hamano S., Kitagawa H. Currarino syndrome associated with Hirschsprung's disease: case report and literature review. J Ped Surg Case Rep. 2015;3:308–311. [Google Scholar]