Abstract

Background

The incidence of oral cancer is increasing. Guidance for oral cancer from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) is unique in recommending cross-primary care referral from GPs to dentists.

Aim

This review investigates knowledge about delays in the diagnosis of symptomatic oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) in primary care.

Design and setting

An independent multi-investigator literature search strategy and an analysis of study methodologies using a modified data extraction tool based on Aarhus checklist criteria relevant to primary care.

Method

The authors conducted a focused systematic review involving document retrieval from five databases up to March 2018. Included were studies looking at OSCC diagnosis from when patients first accessed primary care up to referral, including length of delay and stage of disease at time of definitive diagnosis.

Results

From 538 records, 16 articles were eligible for full-text review. In the UK, more than 55% of patients with OSCC were referred by their GP, and 44% by their dentist. Rates of prescribing between dentists and GPs were similar, and both had similar delays in referral, though one study found greater delays attributed to dentists as they had undertaken dental procedures. On average, patients had two to three consultations before referral. Less than 50% of studies described the primary care aspect of referral in detail. There was no information on inter-GP–dentist referrals.

Conclusion

There is a need for primary care studies on OSCC diagnosis. There was no evidence that GPs performed less well than dentists, which calls into question the NICE cancer option to refer to dentists, particularly in the absence of robust auditable pathways.

Keywords: dentists, diagnostic delay, general practitioners, oral cancer, professional delay, referral, squamous cell cancer

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of oral cancer is increasing;1 in 2016, there were 7576 registrations of cancer of the oral cavity, lip, and pharynx in England.2 Targeted or general screening is not recommended in the UK, or internationally.3,4 Diagnosis often follows the reporting of troublesome symptoms to a primary care healthcare professional (HCP). Unfortunately, at diagnosis it is common for the disease to have reached an advanced stage (stage III or IV).5 Clinical stage at diagnosis is recognised as an important prognostic marker;6 the differences in 5-year mortality rates based on staging are marked, with >80% survival in those with localised disease, compared with <30% in those with advanced disease.7 Furthermore, there is a consensus that in oral cancer the greater the diagnostic delay, the more advanced the disease will be at staging.8,9 The radical surgical treatment required in those with advanced disease can result in disfigurement, social isolation, increased levels of morbidity, and infrequently, death.10,11

Oral cancer is usually an oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), and is known to be associated with smoking, alcohol consumption, and the chewing of betel nuts.12,13 It is increasingly recognised that OSCC can be associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) and the transformation of premalignant lesions — erythroplakia (red areas that cannot be diagnosed as any other definable lesion), leukoplakia (white areas that cannot be characterised as any other definable lesion), and erythroleukoplakia (red and white areas that cannot be characterised as any other definable lesion).7,14–16 The risk of transformation from leukoplakia to OSCC has been reported at between 15.6 and 39.2%, and from erythroplakia to OSCC as 51%.14 Chronic irritation by teeth or dentures is a less common associative factor in the development of OSCC.17 Oral cancer is usually lumped together with head and neck cancers or upper aerodigestive cancers in publications, which may include laryngeal and thyroid cancer. Most GPs would consider oral cancer as a separate entity and so it should be considered in isolation by early cancer diagnosis researchers. The National Cancer Diagnosis Audit18 collects information on GP cancer referrals and diagnoses, and uses the tighter definition of oral/oropharyngeal cancer.

Guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Suspected cancer: recognition and referral,19 supports GPs and dentists in the detection of oral cancers, recommending pathways between GPs and dentists, or specialist care. The guidance recommends that GPs refer to cancer specialists if the patient has an unexplained persistent mouth ulcer for 3 weeks, or an unexplained persistent neck lump. It also recommends a within-2-week appointment with a dentist for a lump on the lip or in the oral cavity, or for signs consistent with erythroplakia or erythroleukoplakia. Lastly, it recommends that suspicious lip or oral cavity lumps or signs which the dentist considers are consistent with erythroplakia or erythroleukoplakia should be referred on a cancer proforma by the dentist (Box 1).

Box 1. NICE guidance relating to the referral of oral cancer.19.

Consider a suspected cancer pathway referral (for an appointment within 2 weeks) for oral cancer in patients with either:

unexplained ulceration in the oral cavity lasting for more than 3 weeks; or

a persistent and unexplained lump in the neck

Consider an urgent referral (for an appointment within 2 weeks) for assessment for possible oral cancer by a dentist in patients who have either:

a lump on the lip or in the oral cavity; or

a red or red and white patch in the oral cavity consistent with erythroplakia or erythroleukoplakia

Consider a suspected cancer pathway referral by the dentist (for an appointment within 2 weeks) for oral cancer in patients when assessed by a dentist as having either:

a lump on the lip or in the oral cavity consistent with oral cancer; or

a red or red and white patch in the oral cavity consistent with erythroleukoplakia

How this fits in

In England, cancer policy recommends greater stratification and personalisation of approaches to cancer diagnosis, with systems of external accountability to improve early diagnosis. However, studies on OSCC are usually undertaken by maxillofacial specialist researchers, and lack the detail required to study pathways to diagnosis and referral by GPs. A recent poll found that 61% of people had visited an NHS dentist within the previous 2 years, and 24% had visited a private dentist, leaving 15% of people without dental provision. Evidence for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommendation for referral from GPs to dentists needs to be demonstrated; there is a paucity of primary care research in OSCC diagnosis. This review found no evidence that referral from GPs to primary care dentists shortened the time to diagnosis for patients. There are concerns that communication pathways between GPs and primary care dentists are not reliable for potential OSCC diagnosis.

One study researching the relationship between delay in diagnosis, stage, and mortality20 states that survival rates would increase by 80% if the malignancy was identified and treated earlier. The concept of delay in oral cancer diagnosis has been extensively reported, and is understood to be complex and nonlinear.21 However, the conclusions drawn are limited by the heterogeneous criteria by which diagnostic delay is defined, variations in research methodology, and a lack of detail surrounding diagnosis and pathways in primary care.8,22 Original research commonly uses a theoretical model investigating delay within a binary classification: patient delay (defined as the interval between detection of awareness of a bodily change to the first consultation with a healthcare professional), and professional delay (defined as the interval between first professional consultation and definitive histological diagnosis of malignancy).21,23,24

There are a number of dynamic factors involved in the early diagnosis of oral cancer from a primary care perspective, including GP and dentist professional knowledge of oral cancer, provision of primary care services, impact of the doctor–patient relationship, and optimisation of suspected oral cancer pathways.25 It is timely to assess the primary care component of the diagnostic journey of oral cancer in light of the 2015 updated NICE cancer guidance.19

This review aims to investigate and contribute to knowledge about the primary care component of the patient journey in diagnosis, and possible delays in symptomatic OSCC diagnosis, specifically the contribution of GPs.

METHOD

Literature search

A study protocol was designed that involved a multi-investigator search strategy and document retrieval process. Five journal databases (MEDLINE, PubMed, ProQuest, EBSCO Health, and Google Scholar) were searched up to March 2018. The search strategy used both medical subject headings (MeSH) and free-text terms: (oral cancer OR oral neoplasm OR oral malignant or mouth cancer) AND (diagnostic delay OR diagnosis or delay). The reference lists of retrieved articles were scrutinised to identify further studies for potential inclusion within the review.

For inclusion within this review studies had to meet the following criteria:

study design presents original data;

exposure of interest is any component of the patient journey involving primary care (ranging from the patient decision to access primary dental/medical services for an oral complaint to the point at which the patient is referred to secondary or tertiary care);

the component of the patient journey is clearly defined, with a specific start and endpoint;

the pathological focus is confirmed primary squamous cell malignancy of the oral cavity or oropharynx; and

the reported outcome is documented as at least one of the following: length of delay, impact of timeliness of diagnosis, stage of disease at time of definitive diagnosis.

Data collection and extraction

Titles of the studies yielded from the search strategy were reviewed by two researchers across all five online databases in an unblinded, but independent, process. Screening of the abstracts was independently performed by all three researchers using an abstract screening tool (further information is available from the authors on request). Any paper that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria proceeded to full-text eligibility assessment, in which all three researchers independently and blindly validated studies against a full manuscript screening tool (further information is available from the authors on request). Disputes at the abstract screening stage and full-text eligibility assessment were resolved by consensus between the three authors.

Data analysis

A data extraction form was used to collect the pertinent data, and record conclusions from the included studies (further information is available from the authors on request). A descriptive synthesis of these studies was then completed, summarising key findings and quality components.

Analysis of study design

The Aarhus checklist for research in early cancer diagnosis was used as a framework to assess the methodological and theoretical base underpinning the selected studies (further information is available from the authors on request).22 This 20-item checklist contains seven questions relating to definitions of time points and intervals, and 13 questions related to measurements (three general questions, eight for studies using questionnaire and/or interviews, and two for studies using primary case-note audit or database analysis). A number of checklist items were excluded as a result of the focused nature of this review. Each study was allocated a total score depending on research methodology, with 13 being the maximum in those studies using questionnaire and/or interview methodology, and six the maximum score in studies using primary case-note audit or database analysis.

RESULTS

Data source

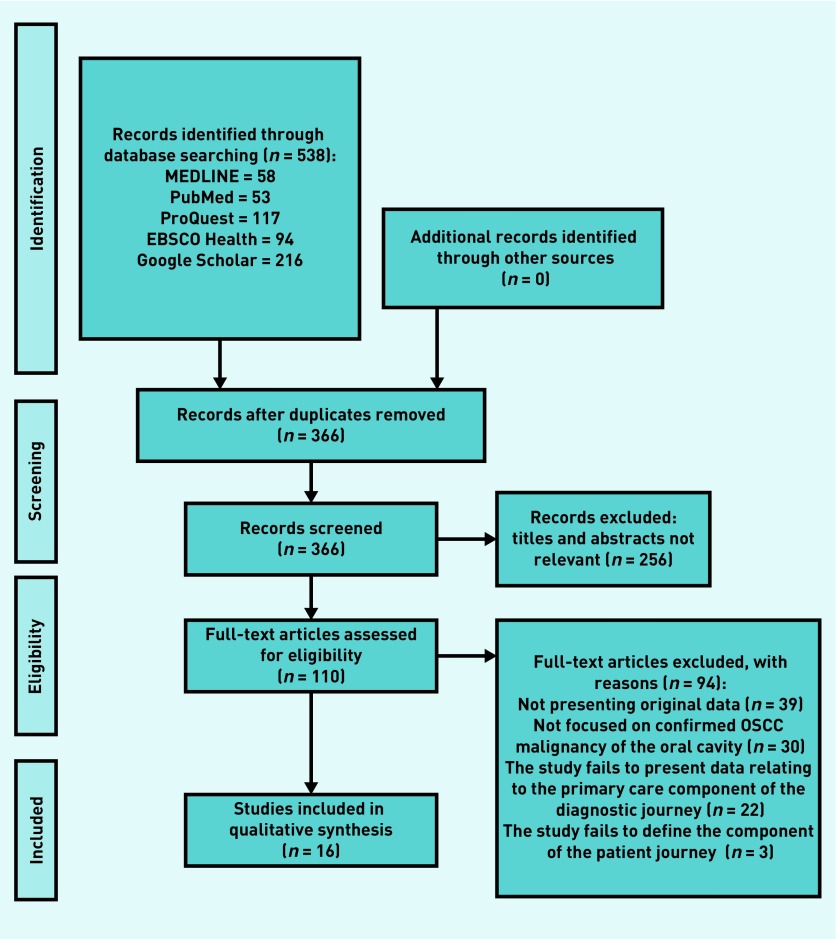

Initial searching of the five databases yielded 538 records, with 366 remaining after de-duplication. Following title and abstract screening an additional 256 citations were removed, leaving 110 articles requiring full-text eligibility assessment. The full texts of 110 articles were assessed against the inclusion criteria (Table 1), resulting in a total of 16 articles being included in the final qualitative review (Table 2). Of the 94 citations excluded at the full-text eligibility stage, 39 were eliminated due to the presentation of non-original data, 30 excluded due to a failure to report on confirmed OSCC, a further 22 failed to present outcomes relating to the primary care component of the diagnostic journey, and three failed to clearly delineate the component within the patient journey (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria, with accompanying rationale

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Research presents original data | Commentaries, insights, letters to the editor, systematic review and/or meta-analysis, and literature reviews | Allowing for the assessment of quality, bias, and extraction of data for qualitative/quantitative synthesis |

| The exposure of interest is any component of the patient journey involving primary care. This ranges between the patient deciding to access dental services/primary medical care for an oral complaint, to the point at which the patient is referred to secondary or tertiary care | Study presents data solely on the patient journey component from the onset of symptoms to the decision to access dental services/primary medical care for an oral complaint, and/or from referral to secondary or tertiary care to diagnosis | Allows for the synthesis of evidence relating to the primary care component of the diagnostic journey |

| The patient journey component is clearly defined, with a specific start and endpoint | Study fails to define the component within the patient journey | Required to ensure the component described relates solely to the primary care component of the diagnostic process |

| The pathological focus is confirmed primary squamous cell malignancy of the oral cavity or oropharynx | The pathological focus is non-primary oral malignancy, non-squamous cell malignancy of the oral cavity or oropharynx, or malignancy of other anatomical locations. All studies investigating screening or diagnostic tools in both healthy and diseased populations are to be excluded | The focus of this review is squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity and oropharynx, and thus study of other types of malignancy would not be in line with the overarching research question |

| The reported outcome is documented as length of delay, impact on diagnostic timing, stage of disease at time of definitive diagnosis | Study fails to document an outcome relating to the diagnostic pathway | The outcome of the primary care component is required to answer the overarching research question |

| Study is written in English | Study not written in English (where there is no translated version available) | No translation services are available to the authors |

| No study is to be excluded based on geographical location or date of publication | ||

Table 2.

Main outcomes relating to primary care component of the oral cancer diagnostic journey

| Publication details | Study design and participant information | Primary care focus | Outcome relating to primary care |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scott et al, 2005 UK26 | Structured interviews 245 patients with oral cancer |

Stage of disease at diagnosis by referring healthcare professional |

Stage at diagnosis by referring HCP: GP: Stage I or II: 41.3% Stage III or IV: 58.7% (stage I/II versus stage III/IV): OR 1.85, 95% CI = 0.8 to 4.1 Dentist: Stage I or II: 56.6% Stage III or IV: 43.4% or (stage I/II versus stage III/IV): 1.0 (reference) |

| Scott et al, 2006 UK27 | Semi-structured interviews 17 patients with oral cancer |

Deterrents from accessing GP/dental practice |

Narrative as provided by patients: ‘I was having trouble getting an NHS dentist and didn’t want to pay for an expensive private dentist’ ‘Nearest appointment at dentist was over a week, so I didn’t bother’ |

| Rogers et al, 2007 UK28 | Case-series analysis 559 patients with cancer of the mouth or oropharynx |

Length of delay in sending referral from primary to secondary care Time interval from presentation in primary care to referral being sent Referral delay by referral destination |

Interval between primary care consultation and referral being sent to secondary care: 78% (n= 253) of referrals were sent on the same day as the consultation (GP and dentist) 11% (n= 36) of referrals were sent 21 days after the consultation If referral was delayed by at least 1 day, the median time for the referral to be sent was 17 days (IQR 7 to 42 days) Interval between first presentation in primary care and referral being sent to secondary care: GP: n= 194 mean 22 days, IQR 12 to 48 Dentist: n = 174 mean 22, IQR 9 to 65, P= 0.48 Referral delay by referral destination: Delay was found to be 1 week longer if sent to a peripheral hospital compared with the regional maxillofacial unit or university dental school |

| Crossman et al, 2016 UK29 | Structured postal questionnaire 161 patients with oral cancer |

Barriers in visiting a primary medical practitioner Actions from first consultation with GP |

Barriers to visiting a doctor: ‘I didn’t realise the problem or symptoms were serious’ 77% (n= 74) ‘I was too worried about what the doctor might find’ 6% (n= 6) ‘I was too busy to make time to go to the doctor’ 4% (n= 4) ‘I was worried I was wasting the doctor’s time’ 3% (n= 3) ‘I was too scared to go to the doctor’ 2% (n= 2) ‘I found my doctor difficult to talk to’ 1% (n= 1) Actions from first consultation with GP: 53% (n= 58) referred to a specialist at a hospital clinic 22% (n= 24) referred for tests 12% (n= 13) treated for another condition 7% (n= 8) symptom not serious, told to come backif continued 5% (n= 5) symptoms not serious, not told to comeback if continued 1% (n= 1) sent straight to hospital the same day |

| Schnetler, 1992 UK30 | Case-series analysis 96 patients with oral cancer |

Presence of delay by referring HCP Correct diagnosis by referring HCP Practitioner working diagnosis Other HCP management |

Delay by referring HCP (delay defined as > 2 days from physical examination): Dentist: 62.0% delayed (n= 24/39) GP: 36.0% delayed (n= 18/50) Hospital doctor: 14.3% (n= 1/7) Correct diagnosis by referring HCP: Dentist: 20.5% correct (n= 8/39) GP: 52.0% correct (n= 26/50) χ2 test P<0.01 Practitioner working diagnosis: Malignancy: GP: 52% (n= 26) Dentist: 20.5% (n= 8) Infection: GP: 22% (n= 11) Dentist: 31% (n= 31) White patch: GP: 8% (n= 4) Dentist: 10% (n= 4) Chronic ulcer: GP: 4% (n= 2) Dentist: 5% (n= 2) Other actions from first consultation with HCP: Antiviral medication: GP: 30% (n= 15) Dentist: 33% (n= 13) Topical steroids: GP: 4% (n= 2) Dentist: 3% (n= 1) Carbamazepine: GP: 2% (n= 1) Dentist: 0% (n= 0) Dental work: GP: 0% (n= 0) Dentist: 23% (n= 9) |

| Hollows et al, 2000 UK31 | Case-series analysis 100 patients with oral cancer |

Length of delay in sending referral from primary to secondary care Interpretation of referral urgency by secondary care |

Length of delay in sending referral from primary to secondary care: GP: mean 14.5 days, SD 32.3, range 0 to 173 days Dentist: mean 8.4 days, SD 17.6, range 0 to 90 days 69% of patients were referred within 1 week by primary care physician (GP and dentist) Interpretation of referral urgency by secondary care: Dentist: 7% interpreted as urgent GP: 27% interpreted as urgent (χ2= 2.6, 1 df, P= 0.05) |

| Kaing et al, 2016 Australia34 | Case-series analysis 101 patients with oral cancer |

Initial referral destination from first consultation with HCP Actions from first consultation with HCP Total diagnostic delay by referring HCP |

Initial referral destination from first consultation with HCP: Referral to oral medicine surgeon: Dentist: 78.6% (n= 33/42) GP: 49.1% (n= 26/53) Referral to other dental specialist (oral medicine, periodontist): Dentist: 40.5% (n= 17) GP: 20.8% (n= 11) Referral to another medical specialist: Dentist: 0% (n= 0) GP: 20.8% (n= 11) Referral to dentist: Dentist: 0% (n= 0) GP: 11.3% (n= 6) Actions from first consultation with HCP: Antibiotic prescription: Dentist: 40.5% (n= 17/42) GP: 47.2% (n= 25/53) Ulcer management: Dentist: 35.7% (n= 15) GP: 24.5% (n= 13) Extraction: Dentist: 28.5% (n= 12) GP: 0% (n= 0) Reassurance/monitoring: Dentist: 11.9 % (n= 5) GP: 7.5% (n= 4) Biopsy: Dentist: 0% (n= 0) GP: 7.5% (n= 4) Diagnostic delay by referring HCP: Dentist: mean 5.8 months, range 0 to 3 years GP: mean 5.3 months (3.5 months excluding outliers), range 0 to 8 years |

| Jovanovic et al, 1992 Netherlands32 | Case-series analysis 50 patients with oral cancer |

Length of delay by first HCP consulted |

Length of delay by first HCP consulted:

GP (n= 27): 0–4 weeks: 81.5% 5–16 weeks: 14.8% >16 weeks: 3.7% Dentist (n= 12): 0–4 weeks: 67.0% 5–16 weeks: 25.0% >16 weeks: 8.3% |

| Kowalski et al, 1994 Brazil35 | Structured interviews 336 patients with cancer of the mouth or oropharynx |

Stage of disease at diagnosis by referring HCP |

Stage of disease at diagnosis by referring HCP: GP: Stage I or II: 27.3% Stage III or IV: 72.7% Dentist: Stage I or II: 14.3% Stage III or IV: 85.7% |

| Peacock et al, 2008 US40 | Case-series analysis 50 patients with oral cancer |

Primary care component of diagnostic journey |

Time from the patient visiting a primary care clinician to undergoing a biopsy or being referred Mean 35.9 days, range 0 to 280 days |

| Groome et al, 2011 Canada36 | Case-series analysis 2033 patients with oral cancer |

Stage of disease at diagnosis by dentist/doctor status |

Stage of disease at diagnosis by dentist/doctor status:

Participants responding ‘yes’ to ‘do you have a regular dentist?’: Stage I (n= 661): 39.9% Stage II (n= 550): 34.0% Stage III (n= 289): 34.6% Stage IV (n= 524): 32.1% P= 0.03 Participants responding ‘yes’ to ‘do you have a family doctor?’: Stage I (n= 660): 92.6% Stage II (n= 550): 96.0% Stage III (n= 288): 97.6% Stage IV (n= 523): 92.2% P= 0.001 |

| Wildt et al, 1995 Denmark37 | Structured questionnaire 167 patients with oral cancer |

Patient preference of primary medical contact for oral symptoms |

Patient preference of primary medical contact for oral symptoms:

GP: 45% (n= 75) Dentist: 35% (n= 58) ENT specialist: 14% (n= 23) Other: 7% (n= 11) |

| Tromp et al, 2005 Netherlands33 | Structured interviews 306 patients with cancer of the mouth or oropharynx |

Stage of disease at diagnosis versus length of referral delay |

Stage of disease at diagnosis versus length of referral delay (stage I and II versus stage III and IV):a <1 month: 107 versus 50 (OR 1.00) 1–3 months: 49 versus 29 (OR 1.22, 95% CI = 0.69 to 2.17) >3 months: 35 versus 18 (OR 1.10, 95% CI = 0.57 to 2.13) |

| Kantola et al, 2001 Finland38 | Case-series analysis 75 patients with oral cancer |

Actions from first HCP consulted with Stage of disease at diagnosis Stage of disease at diagnosis, based on referral patterns |

Referral actions: first HCP consulted with:

Referred for further examination: 65% (n= 49) Scheduled follow-up only: 16% (n= 12) No referral or follow-up: 19% (n= 14) Stage of disease at diagnosis: Stage I and II: 41% (n= 31) Stage III and IV: 59% (n= 44) TNM stage and malignancy grade at diagnosis, based on referral patterns (median): Referred (n= 49): Stage I and II: 51% (n= 25) Stage III and IV: 49% (n= 24) Average malignancy grade: 10 (range 7 to 16) Not referred but followed up (n= 12): Stage 1 and II: 16% (n= 2) Stage III and IV: 84% (n= 10) Average malignancy grade: 12 (range 9 to 14) Neither referred nor followed up (n= 14): Stage I and II: 28% (n= 4) Stage III and IV: 72% (n= 10) Average malignancy grade: range 9 to 16, P= 0.02 |

| Onizawa et al, 2003 Japan39 | Case-series analysis 144 patients with cancer of the mouth or oropharynx |

Delay in referral by HCP Stage of disease at diagnosis by referral delay |

Delay in interval between first presentation to HCP and referral by HCP (defined as >6 days)

Dentist: Delay: 55.3% (n= 47) No delay: 44.7% (n= 38) OR 1.0, 95% CI = referent GP: Delay: 51.7% (n= 15) No delay: 48.3% (n= 14) P= 0.739, OR 0.87, 95% CI = 0.37 to 2.02 T category of disease at diagnosis, based on delay/no delay in referral from primary care (defined as >6 days) T1 category: Delay: 66.7% (n= 16) No delay: 33.3% (n= 8) OR 1.0, 95% CI = referent T2 category: Delay: 51.9% (n= 27) No delay: 48.1% (n= 25) P= 0.231, OR 0.54, 95% CI = 0.20 to 1.48 T3 category: Delay: 29.6% (n= 8) No delay: 70.3% (n= 19) P= 0.010, OR 0.21, 95% CI = 0.06 to 0.69 T4 category: Delay: 48.8% (n= 20) No delay: 51.2% (n= 21) P= 0.165, OR 0.48, 95% CI = 0.17 to 1.36 |

| Kerdpon et al, 2001 Thailand41 | Structured questionnaire 161 patients with oral cancer |

Actions from first consultation with HCP |

Actions from first consultation with HCP:

Referral or biopsy: 52.2% (n= 84) Medication (non-antibiotics): 28.6% (n= 46) Antibiotics: 9.3% (n= 15) Dental work: 5.0% (n= 8) Reassurance: 0.6% (n= 1) |

Referral delay is defined as period between first contact with GP/dentist and first contact with a medical specialist. CI = confidence interval. df = degrees of freedom. ENT = ear, nose, and throat. HCP = healthcare professional. TNM = tumour, node and metastasis. IQR = interquartile range. OR = odds ratio. SD = standard deviation.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. OSCC = oral squamous cell cancer.

Characteristics of studies

Six of the included studies were performed in the UK,26–31 and two in the Netherlands.32,33 There was one study each from Australia, Brazil, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Japan, Thailand, and the US (Table 2).34–41

Nine studies used case-series analysis methodology,28,30–32,34,36,38–40 four used structured interviews,26,27,33,35 and the remaining three studies used patient questionnaires.29,37,41 The number of participants ranged from 17 to 2033 patients (mean 287.6).

Barriers for patients accessing primary care

Two UK studies investigate the barriers experienced by oral cancer patients in presenting to primary care following symptoms.27,29 The most common barrier was the denial of severity, which featured in 77% of patients (n = 74). Only 1% of patients found their doctor difficult to talk to (n = 1).29 One of these studies revealed that in the UK patients found it difficult to get an NHS dental appointment, or refused to pay the fees required for consultation with a private dentist.27

First HCP consulted

Eight studies present data on which HCP initially consulted with patients who were subsequently diagnosed with oral cancer (Table 3).28,32,34,35,37–39,41 In the UK, nearly 50% of patients presented to their GP, and 43% presented to a dentist.28 Only in Japan did patients consult more frequently with a dentist than a GP (59.0% versus 20.1%).39 Presentation patterns varied greatly by country, with >80% first consulting a GP in Finland to 45% in Denmark.37,38

Table 3.

Reported outcomes mapping to specific temporal aspects of the primary care component in the diagnostic journey of oral cancer

| Publication details | Which HCP did the patient first present to? | Number of consultations before referral was made | Referring professionala | Total primary care intervalb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scott et al, 2005 UK26 | – | – | GP: 19.2% (n= 46) Dentist: 22.1% (n= 53) Other: 58.7% (n= 141) |

– |

| Scott et al, 2006 UK27 | – | – | – | – |

| Rogers et al, 2007 UK28 | GP: 49% (n= 254) Dentist: 43% (n= 219) |

– | GP: 49% (n= 254) Dentist: 43% (n= 219) |

General medical: n= 194, mean 22, IQR 12 to 48 General dental: n= 174, mean 22, IQR 9 to 65, P= 0.48 |

| Crossman et al, 2016 UK29 | – | – | GP: 52.3% (n= 91) Dentist: 35.6% (n= 52) |

– |

| Schnetler, 1992 UK30 | – | – | GP: 52.1% (n= 50) Dentist: 40.6% (n= 39) Other: 7.3% (n= 7) |

– |

| Hollows et al, 2000 UK31 | – | – | GP: 56.0% (n= 56) Dentist: 36% (n= 36) |

GP: mean 8.4 days, range 0 to 90, SD 17.6 Dentist: mean 14.5, range 0 to 176, SD 32.2 |

| Kaing et al, 2016 Australlia34 | GP: 52% (n= 53) Dentist: 42% (n= 42) |

GP: mean 2.7, range 1 to 6 Dentist: mean 2.9, range 2 to 5 |

GP: 48.2% (n= 46) Dentist: 50.6% (n= 48) |

– |

| Jovanovic et al, 1992 Netherlands32 | GP: 65.9% (n= 27) Dentist: 29.3% (n= 12) |

– | – | – |

| Kowalski et al, 1994 Brazil35 | GP: 94.9% (n= 319) Dentist: 18.7% (n = 63) Pharmacist: 14% (n= 47) |

– | – | – |

| Peacock et al, 2008 US40 | – | – | – | All primary care physicians: mean 35.9 days, range 0 to 280 |

| Groome et al, 2011 Canada36 | – | – | GP: 66.0% (n= 1525) Dentist: 24.7% (n= 570) Other: 9.5% (n= 231) |

– |

| Wildt et al, 1995 Denmark37 | GP: 45% (n= 75) Dentist: 35% (n= 58) Other: 21% (n= 34) |

– | GP: 45% (n= 75) Dentist: 35% (n= 58) Other: 21% (n= 34) |

– |

| Tromp et al, 2005 Netherlands33 | – | – | – | – |

| Kantola et al, 2001 Finland38 | GP: 81% (n= 61) Dentist: 19% (n= 14) |

– | GP: 81% (n= 61) Dentist: 19% (n= 14) |

– |

| Onizawa et al, 2003 Japan39 | GP: 20.1% (n= 29) Dentist: 59.0% (n= 85) Oral surgeon: 6.25% (n= 9) Other: 14.6% (n= 21) |

– | – | Median 6, quartile deviation 22, range 0 to 240 |

| Kerdpon et al, 2001 Thailand41 | GP: 82.6% (n= 133) Dentist: 15.5% (n= 25) |

Mean 4.3, range 2 to 50 | – | – |

GMP is synonymous with GP, and dental practitioner is synonymous with dentist.

First attendance to referral being sent. IQR = interquartile range. OR = odds ratio. SD = standard deviation.

First actions by the HCP

Four studies (Table 2) provide information on actions taken by the primary HCP following the first consultation they had with patients later diagnosed with oral cancer.29,30,34,41 In a UK population, 53% of patients were referred to secondary care by their GP.29 Importantly, 12% of patients were told their symptoms were not serious by their GP, and nearly half of these were not instructed to re-present if their symptoms continued or progressed. Other than referral to secondary care, another UK study reported that rates of prescribing antiviral medication, topical steroids, and carbamazepine were similar between GPs and dentists.30 Additionally, dentists performed some form of procedural work in 23% of first consultations. In Australia, rates of antibiotic prescribing were found to be similar between dentists and doctors, albeit in higher numbers (40.5% versus 47.2%), and dentists managed or extracted teeth more often than GPs.34

Number of consultations before referral

Two studies provide insight into the number of consultations that patients with oral cancer attended before a referral to secondary care (Table 3).34,41 In Australia, patients first presenting to general practice required, on average, 2.7 consultations before the referral to secondary care was sent (range 1 to 6).34 Similarly, for patients first presenting to a dentist, the average number of consultations was 2.9 (range 2 to 5). In Thailand, the mean number of primary care consultations (dentist and GP) was 4.3 (range 2 to 50).41

The referring HCP

Nine studies provide data on the denomination of the referring primary HCP (Table 3).27–31,34,36–38 Four of the five studies reporting in the UK found that GPs referred 55.5% of patients later diagnosed with an oral cancer;28–31 this is compared with 44.5% referred by dentists.

Stage of disease by the referring HCP

Two studies provided outcomes relating to the stage of disease at diagnosis by referring HCP (Table 2).26,35 A UK study did not find a statistically significant difference in stage of disease at diagnosis between referral by a GP or dentist (odds ratio [OR] 1.85, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.8 to 4.1).26 This finding is corroborated in Brazil.35 Additionally, a study in the Netherlands failed to demonstrate a statistically significant relationship between referral delay (period between first primary care contact and referral being sent) and stage of disease at diagnosis.33

In Canada, a study found statistically significant relationships between stage of disease at diagnosis and participants responding ‘yes’ to the questions ‘Do you have a regular dentist?’ and ‘Do you have a family doctor?’36 It was found that patients responding as having a regular dentist were more likely to have disease at an early stage (stage I and II) (P = 0.03).

Time between decision to refer and referral being sent by the HCP

Four studies provide information on delay between the decision to refer a patient to secondary care, and the referral actually being sent (Table 2).28,30,31,34 In the UK, one study found that nearly 80% of patients are referred the same day as their consultation with the GP or dentist (n = 253).28 However, 11% of patients were referred >21 days following the initial decision to refer (n = 36). This study also failed to demonstrate any difference between doctors and dentists in the delay in the interval between first consultation and referral being sent (dentist and GP mean = 22 days).28 This was a finding corroborated by studies in both the UK and Australia.31,34 Other UK research found that dentists were more likely to delay referral when compared with GPs (by at least 2 days), observed in 62% of cases in dentists and 36% in GPs.30 This is consistent with the findings that dentists undertake dental interventions, and thus potentially delay referral.34

Accuracy of referrals by the HCP

A UK study demonstrated that GPs were more often suspicious of oral cancer than dentists in patients subsequently diagnosed with OSCC (52.0% versus 20.5%, P<0.01).30 Another UK study found that, in secondary care, when staff interpreted referral letters from primary care professionals, 27% from GPs were interpreted as urgent, compared with 7% from dentists (P = 0.05) (Table 2).31

Analysis of research study methodology

The analysis of research methodology (Table 4) revealed that nine studies used questionnaires and/or interviews; their mean score against the Aarhus checklist (maximum 13) was 7.2 (range 5 to 9). Seven studies used case-note analysis methodology; the mean score against the Aarhus checklist (maximum 6) was 4 (range 1 to 6).

Table 4.

Quality assessment scores, adapted from Aarhus checklist for early cancer diagnosis22

| Publication details | Q5: initial presentation (/1) | Q6: referral (/1) | Q8–10: general measurement (/3) | For questionnaires and/or interviews: Q11–18 (/8) | For primary case-note audit Q19–20 (/1) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scott et al, 2005 UK26 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 4 | – | 7/13 (53.8) |

| Scott et al, 2006 UK27 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 5 | – | 9/13 (69.2) |

| Rogers et al, 2007 UK28 | 1 | 1 | 2 | – | 1 | 5/6 (83.3) |

| Crossman et al, 2016 UK29 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | – | 9/13 (69.2) |

| Schnetler, 1992 UK30 | 1 | 0 | 1 | – | 0 | 2/6 (33.3) |

| Hollows et al, 2000 UK31 | 1 | 1 | 3 | – | 0 | 5/6 (83.3) |

| Kaing et al, 2016 Australia34 | 0 | 1 | 2 | – | 0 | 3/6 (50.0) |

| Jovanovic et al, 1992 Netherlands32 | 0 | 0 | 1 | – | 0 | 1/6 (16.7) |

| Kowalski et al, 1994 Brazil35 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | – | 6/13 (45.2) |

| Peacock et al, 2008 US40 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | – | 7/13 (53.8) |

| Groome et al, 2011 Canada36 | 1 | 0 | 2 | – | 1 | 4/6 (67.6) |

| Wildt et al, 1995 Denmark37 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 | – | 6/13 (45.2) |

| Tromp et al, 2005 Netherlands33 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | – | 9/13 (69.2) |

| Kantola et al, 2001 Finland38 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | – | 5/13 (38.5) |

| Onizawa et al, 2003 Japan39 | 1 | 1 | 3 | – | 1 | 6/6 (100.0) |

| Kerdpon et al, 2001 Thailand41 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 3 | – | 7/13 (53.8) |

The studies generally performed well in discussing the complexity of the initial presentation and circumstances of measurement. Less than half (n = 8) of the studies were able to clearly describe the circumstances surrounding the referral. For studies using questionnaire and/or interviews, there was variation in describing the data collection processes and potential biases (0–5/8). The majority of studies using case-note analysis failed to describe the data collection process using clearly defined time points, though acknowledging the limitations of the data.

DISCUSSION

Summary

This review provides valuable insight into a complex and clinically important area of primary care and early oral cancer diagnosis, and highlights the paucity of primary care research in this area. There were only six UK studies in this review, with none cited in general practice. GPs have a pivotal role to play in OSCC diagnosis — nearly 50% of OSCC symptomatic patients present to GPs and not all of the UK population has access to a dentist. There was no clear difference in stage of disease at diagnosis or delay in referral, by the HCP, though dentists introduced some delay by dental interventions. Most referrals were timely. However, less than half of the studies could describe the detailed circumstances surrounding referral, and there was no information concerning inter-GP–dental referrals, as recommended by NICE oral cancer guidelines.19

Strengths and limitations

The majority of studies in this review are authored by maxillofacial specialists, which is surprising considering the research focus is the primary care component of the diagnostic journey. The type of research that can be conducted from the secondary care environment is limited, as evidenced in the qualitative synthesis in this review. First, the studies mostly used retrospective case-note review and questionnaires/interviews, which are subject to response and recall bias. Second, it is difficult for secondary care research to capture any of the barriers faced by patients in accessing primary care, and therefore it cannot draw many significant conclusions in relation to this. Third, there is a gap in available data and understanding on the number of consultations patients have in primary care before referral.

Additionally, there are insufficient data available to understand how HCPs in primary care refer between themselves; this may be different members of the GP team — for example, advanced nurse practitioners — or between GPs and dentists, and between primary care and university dental units, orthodontic units, maxillofacial units, accident & emergency, and ear, nose, and throat (ENT) units. Furthermore, some studies failed to use internationally validated standard questionnaires, or triangulate data collected with the relevant primary HCP.

It is important to consider that the Andersen–Aarhus statement is still yet to be modified to suit certain healthcare systems, which should be recognised as another limitation of this study, especially as more than half of the included studies were conducted in non-UK countries.9 At present, the checklist does not include any specific item on referral delay, defined as the interval between first consultation with a primary HCP and referral (otherwise known as the primary care interval or component of the diagnostic journey). Other limitations of this review include the exclusion of papers that did not include confirmed oral cavity cancer. This meant that studies investigating the knowledge and ability of primary care HCPs to correctly identify pre-malignant or malignant lesions were not included. This area requires specific attention, and has been a focus of the oral cancer recognition toolkit developed in the UK.42 Finally, more than half of the studies included within the qualitative synthesis were conducted in non-UK countries, which limits the transferability of the conclusions drawn.

Comparison with existing literature

The updated NICE guidance for oral cancer in 201519 states that patients with a lump on their lip or in their oral cavity, or who have a red (erythroplakia) or red and white patch (erythroleukoplakia) in their oral cavity, should be sent for assessment for possible oral cancer by a dentist within 2 weeks of seeing their GP. Oral cancer rates are rising,43 and the authors speculate that this guidance may expose patients to an increased risk of delayed referral, because there are no clear auditable referral pathways between doctors and dentists for suspected cancer. In addition, the studies included in this systematic review suggest that dentists may undertake dental procedures and delay OSCC diagnosis. The authors recognise that OSCC is an uncommon cause of mouth ulceration, but for those with OSCC this pathway may not be helpful in reducing time to cancer diagnosis. A small case-series trial modelling the impact of the updated NICE guidance revealed that one in nine diagnoses of oral cancer would be delayed, primarily due to the lack of clear referral pathways.44

Significantly, in the 24-month period up until January 2018, only 50.9% of the adult population was seen by an NHS dentist in England.45 National dental statistics and some review studies demonstrate that being male, low socioeconomic status, patient denial of severity of symptoms, nervousness, financial issues, lack of NHS dentist access, increasing age, need for domiciliary visits, living in a care home, and refugee status are associated with the lowest usage of primary dental care services,46,47 Some of these factors are associated with the greatest risk of developing oral cancer.48

The National Cancer Diagnosis Audit recently published information on all cancers and time from first presentation to GPs with symptoms to first referral.18 It included 6% of all cancer registrations in 2014 in general practices. Oral/oropharyngeal cancer constituted 1.6% of all of the cancers audited. Nearly 60% were referred by GPs on a 2-week-wait proforma, 4.5% referred as urgent, and 7.5% as routine. This audit may not, however, capture dental referrals. The diagnostic interval (the time between first symptomatic consultation with an HCP and the definitive pathological diagnosis) includes a number of important landmarks, including the first investigations ordered by the primary HCP, first referral to secondary care, and the subsequent secondary care component. Oral cancer does not necessarily involve the sequential transition from presentation to primary care, referral to secondary care, and investigations within secondary care leading to a definitive diagnosis. For example, biopsies leading to a pathological diagnosis can be obtained at the primary care level. An interview-based study performed in the UK, however, found that only 15% of dentists in primary care had performed an oral biopsy in the preceding 2 years, with a specialist maxillofacial surgeon citing concerns around lack of skills and delays in referral associated with primary care dentists performing biopsies.49 Dentists’ reluctance to perform a biopsy can mainly be attributed to a possible misdiagnosis of malignancy and risk of litigation.49 Additionally, primary care dentists may be unfamiliar with the varying clinical patterns of oral cancer, because a dentist will only see a handful of cases throughout their career.50 An alternative approach to primary care biopsy includes immediate referral to secondary care.21 This requires GPs and dentists to write high-quality referral letters and use fast-track referral pathways.

Only one study in this review reported on the quality of referral sent between primary and secondary care, with only a minority interpreted as urgent.31 The performance of dentists in this area was almost four times worse than that of GPs. This is a finding corroborated by some other studies investigating the quality of dental referrals to secondary care.51–53

Implications for research and practice

The addition of referral delay to the Aarhus checklist would be of value to primary care stakeholders and researchers.

Achieving World Class Cancer Outcomes: a Strategy for England 2015–2020 54 recommends greater stratification and personalisation of approaches to cancer diagnosis, with systems of external accountability to improve early diagnosis. However, GPs have no electronic or paper trail for referral to dentists, and no electronic or paper trail back. If a GP decides to refer a patient to a dentist as per NICE guidance,19 the emphasis is placed on the patient to attend, regardless of whether they are registered with a dentist, can afford to pay for dental services, or whether there is one readily accessible. NICE acknowledged the problems with cost, and suggested that oral cancer patients are provided with a free pathway to primary care dentists, though it is not clear if this should be after a definitive diagnosis or at the stage of a possible cancer diagnosis. It also acknowledged that community dental costs would increase and cancer costs reduce.19 The authors have not found any evidence for the need for this pathway but there is little research in this area. They urge clinically curious GPs and dentists to publish in this area and report on best pathways to early diagnosis.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank a patient, a survivor of OSCC, who read through this paper.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Cancer Research UK Men twice as likely to develop oral cancer. 2017. Press release. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-us/cancer-news/press-release/2017-11-29-men-twice-as-likely-to-develop-oral-cancer (accessed 10 Oct 2018)

- 2.Office for National Statistics. Cancer registration statistics, England: 2016. ONS; 2018. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/cancerregistrationstatisticsengland/final2016 (accessed 10 Oct 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 3.UK National Screening Committee The UK NSC recommendation on oral cancer screening in adults. UK NSC. 2016 https://legacyscreening.phe.org.uk/oralcancer (accessed 10 Oct 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Speight PM, Epstein J, Kujan O, et al. Screening for oral cancer — a perspective from the Global Oral Cancer Forum. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2017;123:680–687. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2016.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stathopoulos P, Smith WP. Analysis of survival rates following primary surgery of 178 consecutive patients with oral cancer in a large district general hospital. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2017;16(2):158–163. doi: 10.1007/s12663-016-0937-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Massano J, Regateiro FS, Januário G, Ferreira A. Oral squamous cell carcinoma: review of prognostic and predictive factors. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;102(1):67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ragin CCR, Modugno F, Gollin SM. The epidemiology and risk factors of head and neck cancer: a focus on human papillomavirus. J Dent Res. 2007;86(2):104–114. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gómez I, Seoane J, Varela-Centelles P, et al. Is diagnostic delay related to advanced-stage oral cancer? A meta-analysis. Eur J Oral Sci. 2009;117(5):541–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2009.00672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seoane J, Alvarez-Novoa P, Gomez I, et al. Early oral cancer diagnosis: the Aarhus statement perspective. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck. 2016;38(S1):E2182–E2189. doi: 10.1002/hed.24050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerawala CJ. Complications of head and neck cancer surgery — prevention and management. Oral Oncol. 2010;46(6):433–435. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah JP, Gil Z. Current concepts in management of oral cancer — surgery. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:394–401. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brocklehurst PR, Baker SR, Speight PM. Primary care clinicians and the detection and referral of potentially malignant disorders in the mouth: a summary of the current evidence. Prim Dent Care. 2010;17(2):65–71. doi: 10.1308/135576110791013749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abro B, Pervez S. Smoking and oral cancer. In: Al Moustafa AE, editor. Development of oral cancer: risk factors and prevention strategies. New York: Springer; 2017. pp. 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mortazavi H, Baharvand M, Mehdipour M. Oral potentially malignant disorders: An overview of more than 20 entities. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects. 2014;8(1):6–14. doi: 10.5681/joddd.2014.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scully C. Premalignant lesions. Oral Oncol. 2011;47(Suppl 1):S5. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.06.031. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pytynia KB, Dahlstrom KR, Sturgis EM. Epidemiology of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2014;50(5):380–386. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castellarin P, Villa A, Lissoni A, et al. Oral cancer and mucosal trauma: a case series. Ann Stomatol. 2013;4(Suppl 2):9–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swann R, McPhail S, Witt J, et al. and the National Cancer Diagnosis Audit Steering Group Diagnosing cancer in primary care: results from the National Cancer Diagnosis Audit. Br J Gen Pract. 2018. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Suspected cancer: recognition and referral NG12. London: NICE; 2015. (updated 2017). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG12 (accessed 10 Oct 2018) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silverman S, Kerr AR, Epstein JB. Oral and pharyngeal cancer control and early detection. J Cancer Educ. 2010;25(3):279–281. doi: 10.1007/s13187-010-0045-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Varela-Centelles P, López-Cedrún JL, Fernández-Sanromán J, et al. Key points and time intervals for early diagnosis in symptomatic oral cancer: a systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;46(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2016.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weller D, Vedsted P, Rubin G, et al. The Aarhus statement: improving design and reporting of studies on early cancer diagnosis. Br J Cancer. 2012;106(7):1262–1267. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scott SE, Grunfeld EA, McGurk M. Patient’s delay in oral cancer: a systematic review. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2006;34(5):337–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2006.00290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walter F, Webster A, Scott S, Emery J. The Andersen Model of total patient delay: a systematic review of its application in cancer diagnosis. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2012;17(2):110–118. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2011.010113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gómez I, Warnakulasuriya S, Varela-Centelles PI, et al. Is early diagnosis of oral cancer a feasible objective? Who is to blame for diagnostic delay? Oral Dis. 2010;16(4):333–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2009.01642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scott SE, Grunfeld EA, McGurk M. The idiosyncratic relationship between diagnostic delay and stage of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2005;41(4):396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scott SE, Grunfeld E, Main J, McGurk M. Patient delay in oral cancer: a qualitative study of patients’ experiences. Psychooncology. 2006;15(6):474–485. doi: 10.1002/pon.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rogers SN, Pabla R, McSorley A, et al. An assessment of deprivation as a factor in the delays in presentation, diagnosis and treatment in patients with oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2007;43(7):648–655. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crossman T, Warburton F, Richards MA, et al. Role of general practice in the diagnosis of oral cancer. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;54(2):208–212. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schnetler JFC. Oral cancer diagnosis and delays in referral. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;30(4):210–213. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(92)90262-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hollows P, McAndrew PG, Perini MG. Delays in the referral and treatment of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Br Dent J. 2000;188(5):262–265. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jovanovic A, Kostense PJ, Schulten EA, et al. Delay in diagnosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma; a report from The Netherlands. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1992;28B(1):37–38. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(92)90009-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tromp DM, Brouha XDR, Hordijk GJ, et al. Patient and tumour factors associated with advanced carcinomas of the head and neck. Oral Oncol. 2005;41(3):313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaing L, Manchella S, Love C, et al. Referral patterns for oral squamous cell carcinoma in Australia: 20 years progress. Aust Dent J. 2016;61(1):29–34. doi: 10.1111/adj.12314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kowalski LP, Franco EL, Torloni H, et al. Lateness of diagnosis of oral and oropharyngeal carcinoma: factors related to the tumour, the patient and health professionals. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1994;30B(3):167–173. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(94)90086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Groome PA, Rohland SL, Hall SF, et al. A population-based study of factors associated with early versus late stage oral cavity cancer diagnoses. Oral Oncol. 2011;47(7):642–647. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wildt J, Bundgaard T, Bentzen SM. Delay in the diagnosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sc. 1995;20(1):21–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1995.tb00006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kantola S, Jokinen K, Hyrynkangas K, et al. Detection of tongue cancer in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51(463):106–111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Onizawa K, Nishihara K, Yamagata K, et al. Factors associated with diagnostic delay of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2003;39(8):781–788. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(03)00075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peacock ZS, Pogrel MA, Schmidt BL. Exploring the reasons for delay in treatment of oral cancer. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139(10):1346–1352. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kerdpon D, Sriplung H. Factors related to delay in diagnosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma in southern Thailand. Oral Oncol. 2001;37(2):127–131. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(00)00072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.British Dental Association. UK Cancer Research BDA–CRUK Oral cancer recognition toolkit CPD. BDA–CRUK. 2015 https://cpd.bda.org/course/info.php?id=40 (accessed 10 Oct 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gulland A. Oral cancer rates rise by two thirds. BMJ. 2016;355:i6369. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grimes D, Patel J, Avery C. New NICE referral guidance for oral cancer: does it risk delay in diagnosis? Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;55(4):404–406. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2016.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.NHS Digital . NHS dental statistics for England, 2017–18, second quarterly report. NHSD; 2018. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/nhs-dental-statistics/nhs-dental-statistics-for-england-2017-18-second-quarterly-report (accessed 10 Oct 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 46.NHS Digital . Adult dental health survey 2009 — summary report and thematic series. NHSD; 2011. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/adult-dental-health-survey/adult-dental-health-survey-2009-summary-report-and-thematic-series (accessed 10 Oct 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 47.Healthwatch. Access to NHS dental services: what people told local Healthwatch. 2016. Nov, https://ldc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/20161123-HW_0605_DentistryReport_FINAL.pdf (accessed 10 Oct 2018)

- 48.Cancer Research UK . Head and neck cancers incidence statistics. CRUK; https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/head-and-neck-cancers/incidence. (accessed 10 Oct 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Diamanti N, Duxbury AJ, Ariyaratnam S, Macfarlane TV. Attitudes to biopsy procedures in general dental practice. Br Dent J. 2002;192(10):588–592. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ogden G, Scully C, Warnakulasuriya S, Speight P. Oral cancer: two cancer cases in a career? Br Dent J. 2015;218(8):439. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McAndrew R, Potts AJC, McAndrew M, Adam S. Opinions of dental consultants on the standard of referral letters in dentistry. Br Dent J. 1997;182(1):22–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4809288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bjorkeborn M. Quality of oral surgery referrals and how to improve them. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2017;9:111–116. doi: 10.2147/CCIDE.S138201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Izadi M, Gill DS, Naini FB. A study to assess the quality of information in referral letters to the orthodontic department at Kingston Hospital, Surrey. Prim Dent Care. 2010;17(2):73–77. doi: 10.1308/135576110791013712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Independent Cancer Taskforce. Achieving world class cancer outcomes. A strategy for England 2015–2020. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/sites/default/files/achieving_world-class_cancer_outcomes_-_a_strategy_for_england_2015-2020.pdf (accessed 10 Oct 2018)