Abstract

Introduction

The majority of HIV-TB co-infection worldwide is reported in Africa. The risk of developing extra-pulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB) increases as immune deficiency progresses but is difficult to diagnose. Point-of-care ultrasonography (POCUS) can be an effective adjunct to identify and treat EPTB-associated findings using the focused assessment with sonography for HIV-associated TB (FASH) protocol.

Case report

Three HIV-infected patients without known history of EPTB presented to a Rwandan district hospital with fever and unclear infection. Initial testing did not reveal a source. Each patient was then evaluated with the FASH protocol by a Rwandan emergency physician with POCUS training. All patients had findings suggestive of EPTB by ultrasound. Anti-TB treatment was initiated, and all subsequently demonstrated symptom improvement.

Discussion

This case series demonstrates the additional clinical information obtained. It describes how management was changed using POCUS and the FASH in a resource-limited setting in Rwanda and calls for further FASH protocol validation studies.

Keywords: HIV, Tuberculosis, Extra-pulmonary tuberculosis, Ultrasound, Point-of-care ultrasound, Infectious disease, Tropical disease, Emergency ultrasound, Case report, Case series

Abstract

Introduction

La majorité des co-infections VIH-TB dans le monde sont signalées en Afrique. Le risque de développer une tuberculose extra-pulmonaire (EPTB) augmente à mesure qu’évolue le déficit immunitaire, mais elle est difficile à diagnostiquer. L’échographie là où les soins sont prodigués (POCUS) peut être un complément efficace pour identifier et traiter des résultats liés à l’EPTB à l’aide du protocole d’évaluation ciblée utilisant l’échographie de la tuberculose associée au VIH (FASH).

Rapport de cas

Trois patients infectés par le VIH sans antécédents connus d’EPTB se sont présentés à un hôpital de district rwandais avec de la fièvre et une infection indéterminée. Les tests initiaux n’ont pas révélé d’origine. Chaque patient a ensuite été évalué par le biais du protocole de FASH par un médecin d’urgence rwandais formé à la POCUS. Tous les patients présentaient des signes évocateurs de l’EPTB à l’échographie. Le traitement anti-TB a été initié, et tout a démontré par la suite une amélioration des symptômes.

Discussion

Cette série de cas confirme les informations cliniques supplémentaires obtenues. Elle décrit comment la prise en charge a été modifiée en utilisant la POCUS et la FASH dans un contexte de ressources limitées au Rwanda et appelle à d’autres études de validation du protocole de la FASH.

African relevance

-

•

The majority of HIV-TB co-infection cases (78%) are reported in sub-Saharan Africa.

-

•

Extra-pulmonary TB risk increases as immune deficiency progresses.

-

•

Proportion of autopsy-proven TB in HIV-infected people in sub-Saharan Africa is high.

-

•

Ultrasonography can be helpful in identifying Extra-pulmonary TB-associated findings.

Introduction

Over six million new cases of tuberculosis (TB) were diagnosed worldwide in 2014,1 and approximately 15–20% of all TB cases are extra-pulmonary (EPTB).2 HIV-infected persons are up to twenty-six times more likely to develop TB compared with those who are HIV-negative. The majority of these HIV-TB co-infection cases (78%) is reported in sub-Saharan Africa.1

In the setting of advanced HIV, the diagnosis of TB may be more difficult due to atypical clinical presentations, undiagnosed HIV infection, and disease involvement of occult sites, where sputum testing is often negative for mycobacteria.2 The risk of developing extra-pulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB) increases as immune deficiency progresses, with studies showing 45–56% prevalence of EPTB in AIDS cases.1 This combination of factors results in a high proportion of undiagnosed TB found in autopsy studies of HIV-infected people in sub-Saharan Africa.1

Clinicians trained in ultrasound use are often scarce in low-resource settings where EPTB may be more prevalent. However, when available, ultrasonography can be a helpful adjunct in identifying and treating abnormal EPTB-associated findings using the focused assessment with sonography for HIV-associated TB (FASH) protocol.3 EPTB commonly manifests as abdominal TB, pleural or pericardial effusions. This ultrasound protocol evaluates for the presence of pathological fluid collections in the pleural, pericardial and peritoneal spaces, abdominal lymphadenopathy, and hypoechoic lesions in the spleen or liver (concerning for abscess) which may be seen in HIV and TB co-infected patients.4 A definitive diagnosis of TB can only be made by culturing Mycobacterium tuberculosis organisms from a specimen obtained from the patient, and EPTB treatment includes anti-TB medications as well as addressing focal findings as clinically indicated, such as draining pericardial or pleural effusions. Suspected cases of EPTB should also be assessed for concomitant pulmonary TB.

The three cases described herein add to the literature by demonstrating the further clinical information that can be obtained by incorporating point-of-care ultrasound and the FASH protocol into the evaluation of HIV patients with concern for EPTB. These cases were managed by a Rwandan emergency physician with training in point-of-care ultrasound working at a district hospital reporting an average of 100 cases of TB per year.5 All patients verbally consented to inclusion in this case series. Masaka District Hospital is an urban 150 bed mid-level hospital in Kicukiro District, Kigali. It serves a population of 320,000 people,6 and is staffed by general practitioner physicians and registered nurses. There is one emergency medicine trainee with an on-site rotation at this hospital for a period of one year. Available resources include an emergency centre, basic laboratory testing, X-ray in radiology area (but not portable to the emergency centre), and point-of-care ultrasound if a trained clinician is present. There is no dedicated sonographer or radiologist for the hospital, and no on-site CT capacity. GeneXpert testing for TB is only available as a send-out test.

Case 1

A 35 year-old male presented with fever, night sweats and vomiting for three days. He was known to be HIV-infected on anti-retroviral (ARV) therapy and prophylactic trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, with a most recent CD4 T-lymphocyte count of 41 cells/mm3. His exam revealed a temperature (T) of 39 degrees Celsius (°C), heart rate (HR) of 87 beats/min, blood pressure (BP) of 98/70 mmHg, and respiratory rate (RR) 22 breaths/min with oxygen saturation of 98% on room air (RA). His exam was otherwise unremarkable.

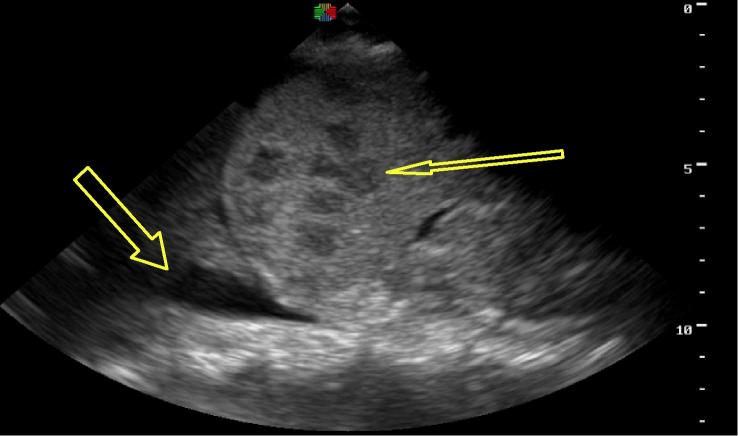

The patient was initially managed as infected with an unclear source. Differential included bacterial, viral, fungal or malignant source. Cefotaxime and intravenous (IV) fluids were initiated and he was admitted to the hospital. Initial labs including blood smear, blood culture, and urinalysis were within normal limits. Cryptococcus antigen testing (blood) and chest X-ray were negative. GeneXpert testing for TB was not available at this time. Antifungal treatment with fluconazole was added to his ongoing antibiotics and ARVs but his fever persisted two weeks into his admission despite this treatment. The FASH ultrasound exam was then performed, revealing small pleural effusions, free fluid in the abdomen, enlarged para-aortic lymph nodes, and splenomegaly with multiple hypoechoic lesions concerning for micro-abscesses (Fig. 1). These findings supported the clinical concern for EPTB and he was started on anti-TB regimen of rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol (RHZE). His fever resolved two days later and he was discharged on this anti-TB regimen.

Figure 1.

Pleural effusion and microabscesses in spleen, patient from Case 1.

He did well at interim local follow-up visits until one month after discharge when he developed intermittent fever, diarrhoea and vomiting. On hospital admission, his exam and diagnostics were unchanged from previous, except for elevated liver function tests. Repeat chest X-ray remained normal. FASH exam again showed findings unchanged from his initial FASH evaluation. An abdominal CT-scan with contrast was completed off-site at a regional referral hospital. It corroborated the ultrasound findings, demonstrating splenomegaly with microabscesses, mesenteric and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy, and hepatomegaly. The official radiologist’s read gave a differential diagnosis of EPTB or disseminated fungal infection. Considering no response to initial anti-fungal treatment, the patient was continued on treatment for EPTB. He improved and was subsequently discharged. Of note, there was no definitive diagnosis made in this case but the FASH findings were helpful in narrowing the differential diagnosis.

Case 2

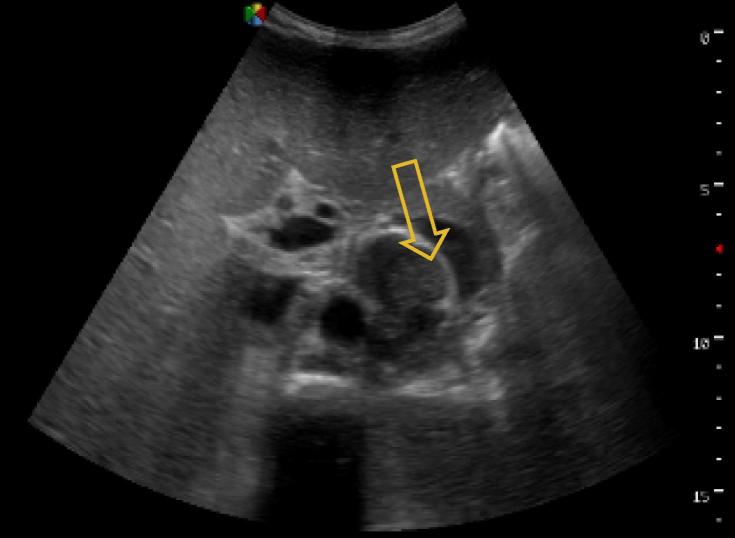

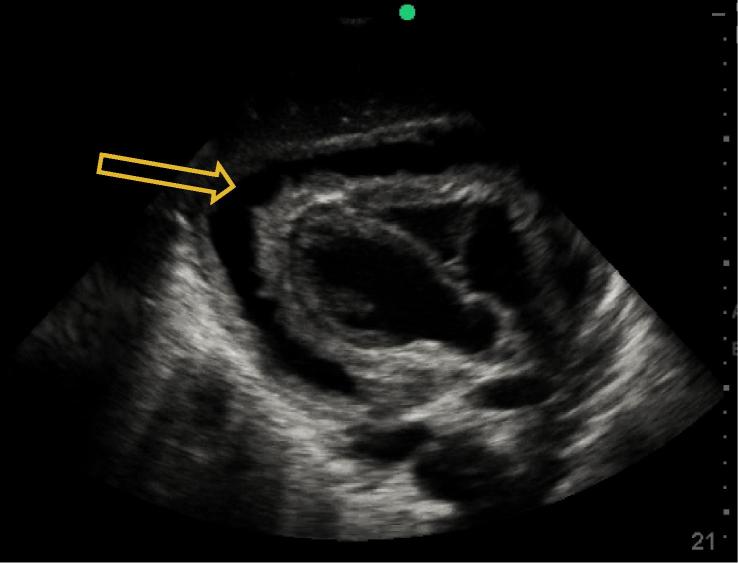

A 32 year-old male patient presented with one month of fever and generalised weakness. He was HIV-infected on ARV therapy, with an undetectable CD4 T-lymphocyte count. Of note, he had a previous history of pulmonary TB one year before, and was treated with negative sputum testing thereafter. Vital signs on presentation were notable for T 38 °C and HR 125 but were otherwise unremarkable. He had generalised wasting but an otherwise non-focal exam. He was managed as a septic patient with unknown source and was started on IV ceftriaxone and IV fluids. His initial lab workup revealed a white blood cell count (WBC) of 0.79 × 10(9)/L, haemoglobin (Hb) 8.2 g/L, platelets (PLT) 177 × 10(9)/L and an elevated creatinine to 4.53 mg/dL. Liver function tests were normal, and peripheral blood smear for malaria, Cryptococcus antigen from blood, chest X-ray and initial GeneXpert TB sputum testing were all negative. After one week on IV antibiotics, the patient continued having fevers and was not improving. EPTB was then considered and the FASH examination performed, which revealed free fluid throughout the abdomen, enlarged para-aortic lymph nodes and splenic microabscesses (Figure 2, Figure 3). The patient was immediately started on anti-TB treatment (RHZE) for concern for EPTB. Shortly thereafter, repeat GeneXpert TB testing from sputum returned positive. The patient was treated in-hospital for one month with improvement, and was then discharged to continue anti-TB medication at home.

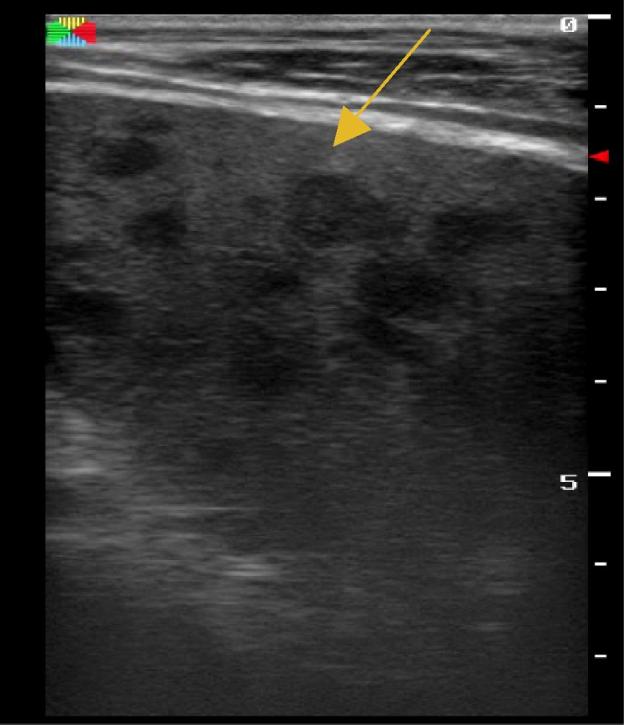

Figure 2.

Splenic microabscesses seen more easily with high frequency ultrasound transducer, patient from Case 2.

Figure 3.

Enlarged para-aortic lymph nodes, patient from Case 2.

Case 3

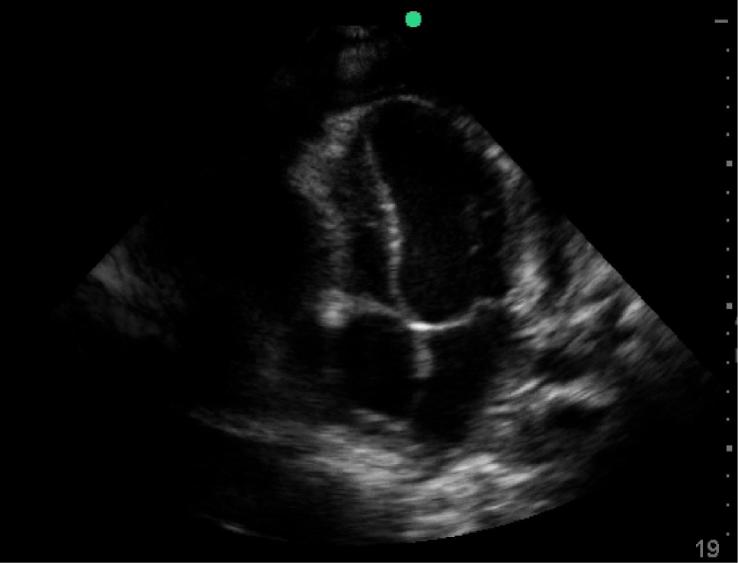

A 32 year-old male patient presented with a chief compliant of shortness of breath. He had been having fever, night sweats, progressive weight loss and dry cough for one month. He had recently been diagnosed of HIV with a CD4 T-lymphocyte count of 373 cells/mm3. He had been started on ARV and prophylactic trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and sputum analysis five days prior was negative for TB. His exam demonstrated distended neck veins and muffled heart sounds. His vital signs showed T 38 °C, HR 105, BP 80/40, RR 25 and oxygen saturation of 87% RA. Point-of-care ultrasound was done which showed a large circumferential fibrinous pericardial effusion with concern for right ventricular collapse consistent with cardiac tamponade (Figure 4, Figure 5), as well as small bilateral pleural effusions and a small amount of free fluid in the abdomen. Resuscitation with oxygen and IV fluids was initiated and a pericardiocentesis was performed with drainage of 150 cc of blood-stained fluid. His vital signs and symptoms improved, the fluid was sent for GeneXpert TB analysis, and he was started on an anti-TB regimen (RHZE). Transfer to chest X-ray was initially not possible because of his instability, but when completed it confirmed bilateral pleural effusions and demonstrated diffuse infiltrates.

Figure 4.

Circumferential pericardial effusion, patient from Case 3.

Figure 5.

Pericardial effusion with right ventricular collapse, patient from Case 3.

Fluid was subsequently positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis consistent with the clinical concern for pulmonary and EPTB. He improved during his two week hospital course and was discharged home to continue anti-TB medication.

Discussion

The cases above demonstrate the utility of point-of-care ultrasound, specifically the FASH examination, as an adjunctive clinical tool to evaluate for EPTB in HIV co-infected patients. Training in and use of point-of-care ultrasound has recently expanded in Rwanda, and while HIV prevalence is lower in Rwanda than in many other settings in sub-Saharan Africa, it is still considered a high prevalence country by the World Health Organization and diagnostics to evaluate for EPTB in the district hospital setting are still limited.7

The FASH protocol has been taught to clinicians in a variety of settings and is widely used at the point-of-care in South Africa.8 This case series demonstrates the additional clinical information obtained and how management was changed using point-of-care ultrasound and the FASH in a resource-limited setting in East Africa and calls for further validation studies for the FASH protocol. In one reported case, CT scan of the abdomen confirmed the FASH findings by ultrasound. Cases 1 and 2 had no chest X-ray findings, normally the first step in TB diagnosis,9 and sputum GeneXpert testing was not able to be obtained in Case 1 and was initially negative in Case 2. Case 3 had an emergent presentation where the FASH exam immediately raised the clinical suspicion for both pulmonary and EPTB, later with confirmatory GeneXpert testing for TB. While Case 1 lacked a definitive diagnosis, TB was confirmed in Case 2 and 3 based on further testing that was initiated after the FASH findings.

Though the FASH exam does not provide a definitive diagnosis of EPTB, abdominal lymphadenopathy, pericardial effusion, pleural effusions, free fluid in abdomen and splenic or hepatic lesions are the abnormal findings which raise suspicion and may help lead to the diagnosis of EPTB. Not all findings are necessary but concern for EPTB increases based on the combination of findings taken with the clinical history. Abdominal lymphadenopathy, pleural effusion and splenic lesions were the most common findings at diagnosis among a cohort of HIV-positive patients with a culture-proven diagnosis of EPTB.8

In resource-limited areas with high HIV and TB prevalence, ultrasound findings may be used to start empiric anti-TB therapy where bacteriologic or histologic confirmation is not available.8 This was the setting for this case series as other definitive diagnostic testing was not available on-site, but EPTB was the most likely diagnosis as all our patients responded favourably to anti-TB treatment when initiated. This case series was limited by one patient that did not have definitive TB diagnosis, and no post-discharge follow-up in the remaining two. Overall, the FASH findings must be interpreted within the patient’s clinical context and local patterns of disease, and it is important to consider other or concurrent diagnoses in these immune deficient patients.

Conclusion

Point-of-care ultrasound and the FASH examination may be helpful adjuncts for physicians working in HIV and TB-endemic settings with limited diagnostic resources but concern for EPTB. Evaluation with ultrasound allows physicians to obtain collateral clinical information, aiding rapid decision-making to manage sick, undifferentiated HIV-infected patients. This case series calls for further validation studies as it suggests that in low-resource settings where other diagnostic modalities are limited and ultrasound is readily available, the FASH ultrasound protocol may avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment that could impact morbidity and mortality.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Dissemination of results

These cases were shared at a conference of the Rwandan Emergency Medicine Residency and during an ultrasound teaching session at Masaka District Hospital.

Author contribution

The authors have all contributed equally to the conception of the work; the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of cases presented; drafting and revising; final approval of the version to be published; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Hein Lamprecht (Division of Emergency Medicine, Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa) for his initial training in the FASH protocol.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of African Federation for Emergency Medicine.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2014. WHO/HTM/TB/2014.08, <http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/137094/1/9789241564809_eng.pdf> [last accessed 20th January 2016].

- 2.Sharma S.K., Mohan A. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Indian J Med Res. 2004;120(4):316–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heller T., Wallrauch C., Goblirsch S. Focused assessment with sonography for HIV-associated tuberculosis (FASH): a short protocol and a pictorial review. Crit Ultrasound J. 2012;4(1):1. doi: 10.1186/2036-7902-4-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel M.N., Beningfield S., Burch V. Abdominal and pericardial ultrasound in suspected extrapulmonary or disseminated tuberculosis. S Afr Med J. 2011;101(1):39–42. doi: 10.7196/samj.4201. < http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21626980> [last accessed 5th November 2015] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Republic of Rwanda Ministry of Health Annual Report July 2012–June 2013. <http://www.moh.gov.rw/fileadmin/templates/Press_release/MoH_Annual_Report_July_20 12-June_2013.pdf [last accessed 20th January 2016].

- 6.Republic of Rwanda 2012 Population and Housing Census, National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda. November):1-50, <http://www.lmis.gov.rw/scripts/publication/reports/Fourth%20Rwanda%20Population%20and%20Housing%20Census_Housing.pdf>; 2012 [last accessed 26th January 2016].

- 7.Rwanda: WHO statistical profile. <http://www.who.int/gho/countries/rwa.pdf> [last accessed 12th March 2016].

- 8.Heller T., Wallrauch C., Brunetti E. Changes of FASH ultrasound findings in TB-HIV patients during anti-tuberculosis treatment. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18(7):837–839. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.13.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heller T., Goblirsch S., Bahlas S. Diagnostic value of FASH ultrasound and chest X- ray in HIV-co-infected patients with abdominal tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17:342–344. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]