Key Points

Question

Are psychotic experiences associated with an increased risk of later suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and/or suicide death?

Findings

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of 10 general population cohort studies on 84 285 individuals, psychotic experiences were associated with significantly increased odds of subsequent suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide death. The increase in risk was in excess of that explained by co-occurring psychopathology.

Meaning

Psychotic experiences are clinical markers of risk for future suicidal behavior in excess of the risk associated with co-occurring psychopathology.

This systematic review and meta-analysis examines longitudinal studies on cohorts of individuals with psychotic experiences to determine their likelihood of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide death.

Abstract

Importance

Recent research has highlighted that psychotic experiences are far more prevalent than psychotic disorders and associated with the full range of mental disorders. A particularly strong association between psychotic experiences and suicidal behavior has recently been noted.

Objective

To provide a quantitative synthesis of the literature examining the longitudinal association between psychotic experiences and subsequent suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide deaths in the general population.

Data Sources

We searched PubMed, Excerpta Medica Database, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, and PsycINFO from their inception until September 2017 for longitudinal population studies on psychotic experiences and subsequent suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide death.

Study Selection

Two authors searched for original articles that reported a prospective assessment of psychotic experiences and suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, or suicide death in general population samples, with at least 1 follow-up point.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Two authors conducted independent data extraction. Authors of included studies were contacted for information where necessary. We assessed study quality using the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale. We calculated pooled odds ratios using a random-effects model. A secondary analysis assessed the mediating role of co-occurring psychopathology.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Psychotic experiences and subsequent suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide death.

Results

Of a total of 2540 studies retrieved, 10 met inclusion criteria. These 10 studies reported on 84 285 participants from 12 different samples and 23 countries. Follow-up periods ranged from 1 month to 27 years. Individuals who reported psychotic experiences had an increase in the odds of future suicidal ideation (5 articles; n = 56 191; odds ratio [OR], 2.39 [95% CI,1.62-3.51]), future suicide attempt (8 articles; n = 66 967; OR, 3.15 [95% CI, 2.23-4.45]), and future suicide death (1 article; n = 15 049; OR, 4.39 [95% CI, 1.63-11.78]). Risk was increased in excess of that explained by co-occurring psychopathology: suicidal ideation (adjusted OR, 1.59 [95% CI, 1.09-2.32]) and suicide attempt (adjusted OR, 2.68 [95% CI, 1.71-4.21]).

Conclusions and Relevance

Individuals with psychotic experiences are at increased risk of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide death. Psychotic experiences are important clinical markers of risk for future suicidal behavior.

Introduction

There has been extensive research on psychotic experiences (PEs) in the general population over the past 2 decades. These are hallucinatory experiences and delusional beliefs that are similar to the classic positive symptoms of schizophrenia but typically associated with at least some degree of intact reality testing. Psychotic experiences are reported by 5% to 8% of the general adult population.1 While initial research focused on an increased risk for psychotic disorder in individuals who report PEs,2 much subsequent research has demonstrated that PEs are associated with high risk for a broad range of mental disorders and poor mental health outcomes in general.3,4,5,6,7,8,9

A striking finding in recent research on PEs has been the strong association with suicidal behavior. In the past 5 years, there have been many studies to investigate the risk of suicidal behavior in individuals who report having PEs.10,11,12,13,14 To evaluate PEs as a risk marker for future suicidal thoughts and behavior, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies looking at PEs and risk for suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide death.

Method

Search Strategy

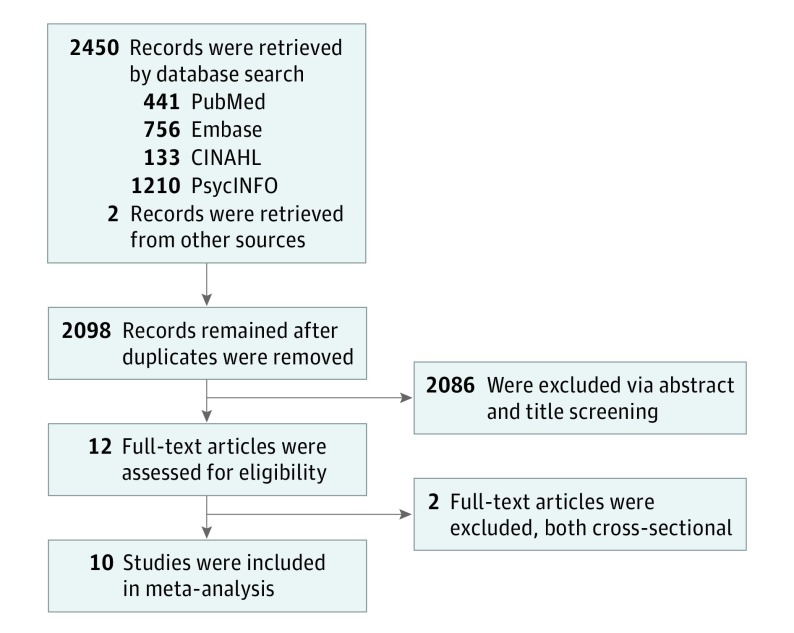

Following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines,15 we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of published longitudinal studies on PEs, and subsequent suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide death (Figure 1). The search strategy was developed in consultation with a research librarian. We searched through electronic databases PubMed, Excerpta Medica Database (Embase), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and PsycINFO from their inception until September 2017 for articles with the following search terms: psychotic experience, psychotic like experience, psychosis like experience, hallucinations, delusion*, psychotic like symptoms, and suicid*. We searched using the format “(("psychotic experiences"[Title/Abstract] OR "psychotic-like experiences"[Title/Abstract] OR "psychotic like experiences"[Title/Abstract] OR "psychosis like experiences"[Title/Abstract] OR "psychosis-like experiences"[Title/Abstract] OR "hallucinations"[Title/Abstract] OR "Delusion*"[Title/Abstract] OR "psychotic-like symptoms"[Title/Abstract] OR "psychotic like symptoms"[Title/Abstract])) AND ((Suicid*[Title/Abstract]) OR suicide[Mesh]).” References within articles were also searched to identify other possible studies. Members of the author team (I.K., J.D., and M.C.) with expertise in this subject area were canvassed to determine if any relevant studies were missing.

Figure 1. PRISMA Style Flow Diagram of Included Studies.

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria were: (1) an original, published article (2) written in English (3) about general population samples and (4) involving prospective assessment of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, or suicide death, (5) with at least 1 follow-up point. We excluded articles for the following reasons: they (1) were not longitudinal, (2) did not report odds ratios, hazard ratios, risk ratios, or data that enabled the researchers to calculate these, and (3) were only published as an abstract or conference summary.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

Two authors (K.Y. and U.L.) conducted the literature search. Data extraction was completed separately and any disagreements were resolved via discussion. A senior reviewer (I.K.) was consulted when necessary.

Synthesis of Results

From each included study, these 2 researchers independently extracted data on the baseline age range of participants, the follow-up period, the psychosis and suicidality measures used, and the figures for suicidality outcome (suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, or suicide death; Table). Where necessary, authors were contacted for further information.

Table. Data Extraction Form of Relevant Data From the 10 Included Studies.

| Source | Country | Sample, No. | Baseline Age, y | Follow-up Period, y | Instrument | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychosis | Suicide | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||||||

| Suicidal Ideation | Suicide Attempt | Suicide Death | Suicidal Ideation | Suicide Attempt | Suicide Death | |||||||

| Bromet et al,29 2017 | 19 countriesa | World Health Organization World Mental Health surveys, 33 370 | ≥18 | NR | Composite International Diagnostic Interview | Composite International Diagnostic Interview | 3.90 (3.58-4.26) |

3.87 (3.42-4.37) |

NA | 2.2 (1.8-2.6)b |

1.9 (1.5-2.5)b |

NA |

| Cederlöf et al,12 2017 | Sweden | The Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden, 9242 | 15 or 18 | 1 mo-5.8 y | Self-report questionnaire | Swedish Patient Register | NA | 1.84 (1.23-2.75) |

NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Connell et al,13 2016 | Australia | Mater–University of Queensland Study of Pregnancy, 644 | 14 | 16-19 | Youth self-report | Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders | 1.60 (1.15-2.24) |

1.97 (1.14-3.40) |

NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Fisher et al,31 2013 | New Zealand | Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development study, 789 | 11 | 27 | Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children | Diagnostic Interview Schedule | NA | 6.45 (2.12-19.62) |

NA | NA | 2.58 (1.10-6.08)c |

NA |

| Honings et al,25 2016 | Germany | The Early Developmental Stages of Psychopathology study, 3021 | 21.7 | 4.8 | Composite International Diagnostic Interview | Composite International Diagnostic Interview | 2.07 (1.50-2.86) |

3.95 (1.85-8.43) |

NA | 1.32 (0.93-1.87)d |

3.44 (1.54-7.69)d |

NA |

| The Netherlands | The Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence study, 7076 | 18-64 | 3 | Composite International Diagnostic Interview | Composite International Diagnostic Interview | |||||||

| The Netherlands | The Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence study 2, 6646 | 18-65 | 3 | Composite International Diagnostic Interview | Composite International Diagnostic Interview | |||||||

| Kelleher et al,14 2013 | Ireland | Saving and Empowering Young Lives in Europe, 1112 | 13-16 | 1 | Adolescent Psychotic Symptoms Screener | Paykel Suicide scale | NA | 9.36 (4.40-19.91) |

NA | NA | 5.90 (3.48-10.01)e |

NA |

| Kelleher et al,28 2014 | Sweden | Swedish Twin Study of Child and Adolescent Development, 2263 | 13-14 | 3 | Youth self-report | Youth self-report | 2.70 (1.40-5.21) |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 16-17 | 3 | Adult self-report | Adult self-report | 2.72 (1.72-4.29) |

||||||||

| Martin et al,27 2015 | Australia | Helping to Enhance Adolescent Living Project, 1896 | 12-17 | 1 | Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children | Self-Harm Behavior Questionnaire, part A | NA | 2.48 (1.07-5.75) |

NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Sharifi et al,30 2015 | United States | Epidemiologic Catchment Area, 15 049 | ≥18 | 24-27 | Diagnostic Interview Schedule | US National Death index | NA | NA | 4.39 (1.63-11.78) |

NA | NA | 2.28 (0.36-14.41)f |

| Sullivan et al,26 2015 | United Kingdom | Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, 3171 | 12 | 4 | Psychosis-Like Symptom interview | Self-report questionnaire | 1.93 (1.50-2.49) |

2.37 (1.68-3.37) |

NA | 1.31 (0.99-1.73)g |

1.75 (1.20-2.54)g |

NA |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; NR, not reported.

Argentina, Colombia, Mexico, Peru, Brazil (São Paulo only), United States, Nigeria, Iraq, Lebanon, China (Shenzhen only), New Zealand, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, and Spain.

Adjusted for age cohorts, sex, person-year dummies, country, and 21 other antecedent mental disorders (mood disorders, anxiety disorder, behavior disorders, eating disorders, and substance use disorders).

Adjusted for age, family socioeconomic status, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder at age 11 years, anxiety, conduct disorder, and depression.

Adjusted for age, sex, continuous depression, anxiety, and mania symptoms.

Adjusted for abnormal or borderline abnormal score on emotional problems, conduct problems, and hyperactivity subscales of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire.

Adjusted for sex, ethnicity, marital status, education, schizophrenia spectrum disorders, depressive disorders, bipolar disorder, phobic disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, alcohol use disorders, other substance use disorders, antisocial personality disorder, and any psychiatric hospital admission.

Adjusted for sex, social class, and self-reported depressive symptoms at age 12 years.

To allow for pooled results, we extracted raw unadjusted data from all studies in which data were available and used these to calculate odds ratios for suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and suicide death in Review Manager (Revman) version 5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration) using a random-effects analysis. Where raw data were not available, we input ORs from the individual studies directly. We also calculated the population attributable fraction for the association between PEs and suicidal ideation and between PEs and suicide attempts and suicide deaths combined.

We used τ as a standard deviation and τ2 to describe the distribution of true effects (ie, as a measure of heterogeneity).16,17 The use of τ and τ2 is considered more appropriate than I2 for reporting heterogeneity because they provide a point estimate of the between-studies variance, whereas I2 is the “proportion of variability in the point estimates that is due to τ2.”18(p1159) In contrast, τ is the variance of the true effects on the same scale as the effect itself. There is no accepted significance level for τ and τ2. Rather, the purpose of τ2 is to assign weights to studies in a random-effects analysis.

Because the follow-up time differed between included studies, we further conducted a meta-regression to see whether the association between PEs and the risk of suicide ideations or attempts changes over time. For this purpose, we used the mean follow-up time for each study.

Secondary Analysis

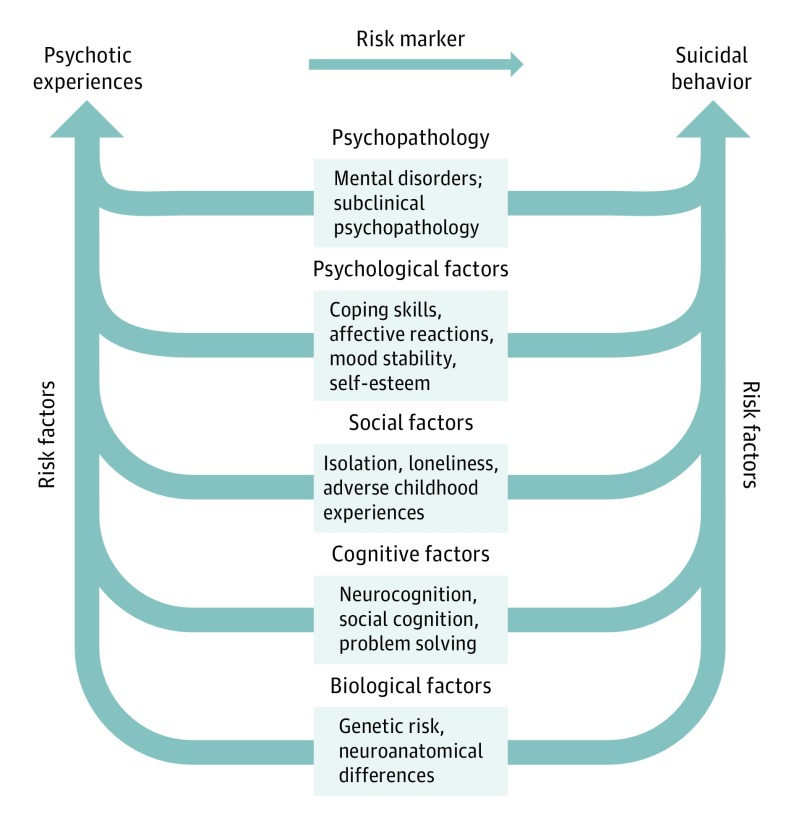

We conducted a secondary meta-analysis of studies that had adjusted their findings for co-occurring psychopathology. This was not because we view psychopathology as a confounder in the association between PEs and suicidal behavior; rather, we consider psychopathology an important mediator in the association, and we wished to investigate whether it fully mediates the association (ie, that the reason for PEs being a risk marker for suicidal behavior is solely because PEs are also markers of risk for psychopathology) or just partially mediates the association (ie, that part but not all of the association is explained by co-occurring psychopathology; Figure 2).

Figure 2. Conceptual Model of the Association Between a Range of Risk Factors and Psychotic Experiences and Suicidal Behavior.

Because of shared risk factors, psychotic experiences function as a risk marker for suicidal behavior.

Study Quality

Study quality was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale.19 This assesses studies on 3 categories: selection (including representativeness of the exposed cohort, selection of nonexposed cohort, and ascertainment of the exposure), comparability (on the basis of design or analysis), and outcome (assessments of outcome, whether follow-up was long enough for outcomes to occur and the adequacy of the follow up of cohorts). Exclusion of individuals with baseline suicidal ideation or suicide attempt, the use of semistructured interviews or validated self-report questionnaires, and the reporting of raw, unadjusted data were criteria for assessments of quality as higher. Quality was assessed from the published articles, supplement materials, and information gathered from the authors of individual studies. The comparability category, which offers a maximum score of 2 for adjusting for 2 variables deemed important (by the researchers evaluating a study, to define the adjustments important to their specific research), is not applicable in this systematic review and meta-analysis. Therefore, we modified the scale so that the maximum total quality score was 8 and offered a score of 1 for this category if articles provided unadjusted odds ratios or the raw data necessary to calculate these. In line with previous research using this scale, we defined a high-quality study as any that scored 6 or more (eTable in the Supplement).20,21,22

Results

Study Selection

Our literature database search yielded 2540 articles, and additional means yielded 2 more. After the removal of duplicates, titles, and (as necessary) abstracts were read to determine articles of relevance. References of included studies were also checked. This identified 12 articles for screening of the full texts. Two of 12 were excluded because they were cross-sectional in design,23,24 leaving 10 articles for inclusion in the review (Figure 1). Of these, 7 studies reported odds ratios (ORs),13,14,25,26,27,28,29 2 studies reported hazard ratios,12,30 and 1 reported relative risk.31

Sample Characteristics

These 10 studies reported on a total of 84 285 participants from 12 different samples and 23 countries (Argentina, Colombia, Mexico, Peru, Brazil [São Paulo only], United States, Nigeria, Iraq, Lebanon, China [Shenzhen only], New Zealand, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Ireland, Sweden, Australia, and the United Kingdom; Table). In the 6 studies that reported sex information, there were 18 241 women (58.3%).

A total of 5920 individuals had suicidal ideation from the 2 studies that reported the raw numbers for this outcome26,28 (of a total 40 111 individuals [14.8%]). Across the 5 studies that provided the raw numbers for suicide attempts,12,14,26,29,31 there was a total of 2208 suicide attempts (of 47 684 individuals [4.6%]). One article looked at completed suicides and reported 24 suicide deaths in their sample of 15 049 individuals.

The follow-up periods from the 10 studies ranged from 1 month to 27 years. The earliest study looked at data from 1980,30 and the latest studies reported baseline data from 2009.12,14 Nine of 10 studies were rated high-quality (eTable in the Supplement).

Meta-analytical Results

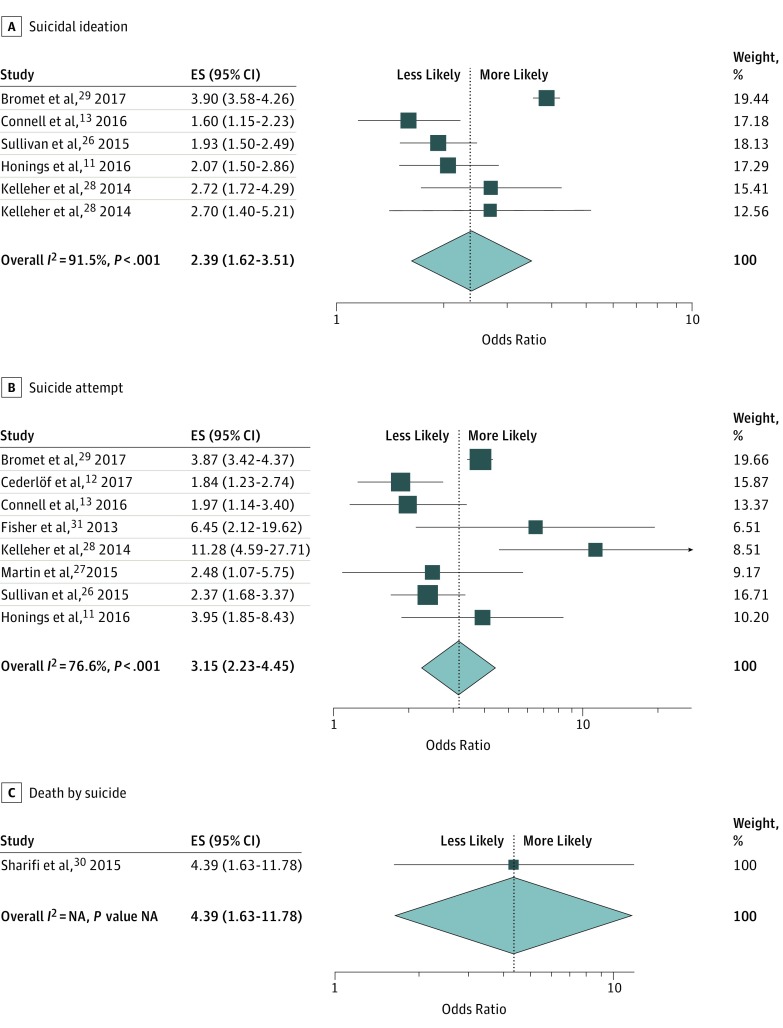

Suicidal Ideation

Five studies reported longitudinal data on suicidal ideation. The τ2 value for studies on suicidal ideation was 0.20. Because there were fewer than 10 studies in this category, it was inappropriate to conduct the Egger test for funnel plot asymmetry32; however, we have included a funnel plot nonetheless to allow visual inspection (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). As the 2014 study by Kelleher et al28 reported data for 2 age ranges at 2 different points (with PEs in individuals aged 13 to 14 years associated with suicidal ideation at age 16 to 17 years and PEs in individuals aged 16 to 17 years associated with suicidal ideation at ages 19 to 20 years), both ORs were entered into the model. Individuals who reported PEs had a 2.39-fold (95% CI, 1.62-3.51) increased odds of suicidal ideation.

Suicide Attempts

Eight studies reported longitudinal data on suicide attempts. The τ2 value for studies on suicide attempts was 0.15. Because there were fewer than 10 studies in this category, it was inappropriate to conduct the Egger test for funnel plot asymmetry32; however, we constructed a funnel plot to allow visual inspection (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). Individuals who reported PEs had a 3.15-fold (95% CI, 2.23-4.45) increased odds of suicide attempt.

Suicide Deaths

Just 1 study reported longitudinal data on suicide deaths.30 Therefore we calculated an odds ratio based on the data from this 1 study. Individuals who reported PEs had a 4.39-fold (95% CI, 1.63-11.78) increased odds of suicide death (Figure 2).

Population-Attributable Fractions

The population-attributable fraction of PEs for suicidal ideation was 11.9%. The population-attributable fraction of PEs for suicide attempts and suicide deaths combined was 24.7%. We were not able to estimate CIs because only 2 of the 5 studies on suicidal ideation provided information on the number of individuals with suicidal ideation among those with and without PEs, and 5 of 8 studies did the same for suicide attempts (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Forest Plot Showing Association Between Psychotic Experiences and Suicidality.

Studies are shown for suicide ideation (A), suicide attempt (B), and suicide death (C). Horizontal lines represent 95% CIs. Diamonds show overall pooled estimate for each subset. The vertical line indicates the mean. ES indicates effect size.

Effect of Follow-up Time

Five studies of suicidal ideation and 7 studies of suicide attempts reported a mean follow-up time. Because there were fewer than 10 studies in each category, it was not appropriate to conduct a formal meta-regression for either33; however, we constructed bubble plots for each category to allow visual inspection (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

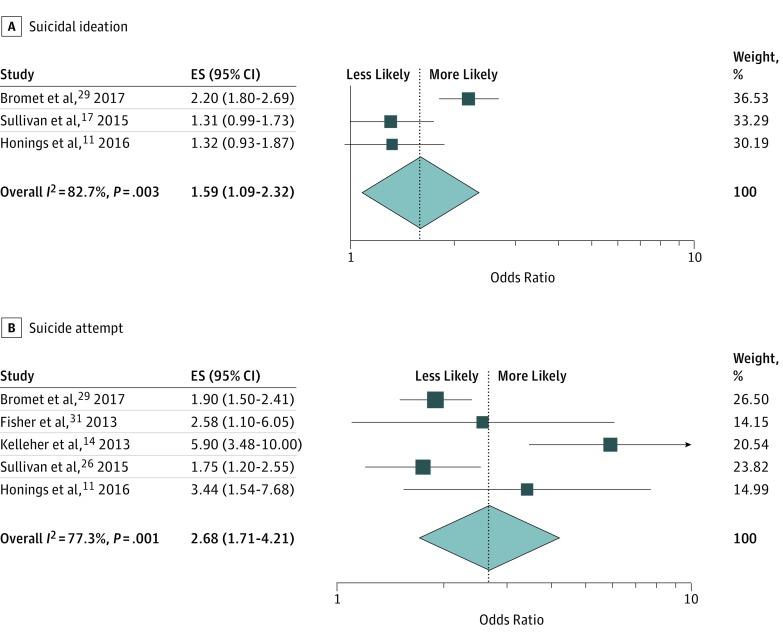

Psychopathology as a Mediator of the Association Between PEs and Risk of Suicidal Ideation or Suicide Attempt

As a secondary analysis, 3 of 6 studies on the association between PEs and suicidal ideation reported odds ratios adjusted for co-occurring psychopathology; the pooled odds ratio was 1.59 (95% CI, 1.09-2.32). Five of the 8 studies on the association between PEs and suicide attempt reported odds ratios adjusted for co-occurring psychopathology. The pooled odds ratio was 2.68 (95% CI, 1.71-4.21; Figure 4).

Figure 4. Forest Plot Showing the Association Between Psychotic Experiences and Suicidality, Adjusted for Psychopathology.

Studies are shown for suicide ideation (A) and suicide attempt (B). Horizontal lines represent 95% CIs. Diamonds show overall pooled estimate for each subset. The vertical line indicates the mean. ES indicates effect size.

Discussion

An association between psychotic disorder and suicidal behavior has long been recognized; in 1911, Bleuler wrote that “the suicidal drive is the most serious of schizophrenic symptoms.”34(p83) Only recently, however, has research extended this finding to recognize an important association between suicidal behavior and not just psychotic disorders, but also the far more prevalent phenomenon of PEs. We identified 10 prospective cohort studies, all published since 2013, that examined the association between PEs and subsequent suicidal ideation, suicidal attempt, and/or suicide death. All studies were consistent in finding a significant association. Our pooled odds ratios showed that individuals who reported PEs had 2-fold increased odds of subsequent suicidal ideation, 3-fold increased odds of subsequent suicide attempt, and 4-fold increased odds of subsequent suicide death.

The mechanisms explaining the association between PEs and suicidal behavior are potentially manifold.35 One hypothesized direct association between PEs and suicidal behavior is that the content of PEs promotes suicidal behavior (for example, hallucinations commanding the individual to harm themselves). However, the content of hallucinations, including the presence of command hallucinations to harm oneself, cannot be said to emerge at random; rather, hallucination content reflects factors present in the thought content of the affected individual. Therefore, command hallucinations to harm oneself may simply reflect underlying suicidal thoughts (as opposed to inducing de novo suicidal thoughts). Regardless, 2 studies in general population samples found that, despite the strong association between PEs and suicidal behavior, direct commands to harm oneself were present in only a minority of cases.23 It could also be the case that distress associated with PEs increases the risk of suicidal behavior.36 In a sample of Australian adolescents with PEs, Martin et al27 found that individuals with co-occurring psychological distress had a higher odds of suicide attempt but that individuals without co-occurring psychological distress did not.

There are multiple other factors that may mediate the association between PEs and suicidal behavior.37 Psychotic experiences are associated with a high prevalence of mental illness, which is itself an important risk factor for suicidal behavior. In fact, individuals with PEs not only have a higher overall prevalence of mental disorders, they tend to have more severe and multimorbid psychopathology, a higher burden of symptoms, poorer global functioning, and more mental health service use than individuals with mental disorders who do not have PEs.5,38,39,40

However, the presence of mental illness is insufficient to explain the association between PEs and suicidality. For one, PEs are associated with increased odds of suicidal behavior even in individuals without a mental disorder.41 Furthermore, studies that have adjusted for the presence of co-occurring psychopathology, including both continuous and categorical measures,16,17,42,43 have found that risk of suicidal behavior exceeds the level that can be explained by mental illness. In the current study, we conducted a secondary analysis on the association between PEs and suicidal behavior to investigate whether co-occurring psychopathology fully mediated the association. We found that co-occurring psychopathology is only a partial mediator of the association between PEs and suicidal behavior; that is, PEs are a marker of risk for later suicidal behavior in excess of the risk associated with co-occurring mental disorders. (Figure 2 includes examples of mediating variables in the association between PEs and suicidal ideation and behavior.)

Interestingly, PEs have also been shown to be markers of risk for suicidal behavior in individuals with suicidal ideation. For example, a study by DeVylder et al10 showed that in a general adult population sample with suicidal ideation, additional information on depressive symptoms did not help to distinguish who among the individuals with suicidal ideation was at increased odds of suicide attempt, but the co-occurrence of PEs did add significantly to suicide attempt prediction. Similarly, in a general adolescent sample with suicidal ideation, Kelleher et al23 showed that the co-occurrence of PEs was associated with greatly increased odds of suicide attempt.

To our knowledge, there has been only 1 study to date that has looked at PEs and suicidal behavior in a clinical population.23 This study found that PEs were not associated with a significantly increased odds of isolated suicidal ideation (that is, suicidal ideation in the absence of a suicide plan or suicide attempt), but that PEs were associated with a 3-fold increased odds of suicide attempt. The authors went on to directly compare diagnostic groups with vs without PEs and found that patients with depression and PEs had a 9-fold increased odds of suicide attempt compared with patients with depression who did not have PEs. Patients with an anxiety disorder and PEs had a 15-fold increased odds of suicide attempt compared with patients with an anxiety disorder who did have PEs. Patients with a behavioral disorder and PEs had a 3-fold increased odds of suicide attempt compared with patients with a behavioral disorder who did not have PEs.

Poorer mathematical and communication skills have also been shown in individuals with PEs,44,45 suggesting that problem-solving skills (a well-established risk factor for suicidal behavior46) may also be impaired in individuals with PEs. In terms of specific neurocognitive domains, researchers have demonstrated poorer processing speed in particular in individuals with PEs.47,48,49 This might suggest that additional (time) pressures during mental challenges may elicit cognitive problems that would not be evident under nonpressured settings. This idea is complemented by neuroimaging findings, which have shown reduced integrity of major white matter tracts in individuals with PEs, which are important in coordinating speeded transmission of information between distributed neural networks.50,51,52 The real-world consequences of this dysfunction may be that stressful or high-pressure situations precipitate problems with thinking and reasoning that would not otherwise be evident in people who are vulnerable to PEs. In the context of high stress and poorer communication skills, this might adversely affect the individual’s ability to formulate logical plans to manage perceived challenges and instead increase the likelihood of turning to suicide.

In a mega-genome wide association study, Pain et al53 demonstrated significant genetic overlap between PEs and both schizophrenia and major depressive disorder risk genes, 2 disorders associated with major risk for suicidal ideation and behavior. Using a convergent functional genomics approach, Niculescu et al54,55,56 showed that many of the top biomarkers for suicide are also biomarkers for psychotic disorders and high hallucination states. In a series of studies of individuals who were hospitalized for suicidal behavior and postmortem brain tissue from individuals who died by suicide, Niculescu et al found that changes in molecular markers that were associated with high hallucination states, such as DOCK5, were also associated with high suicidal states and suggested that a psychosis-like state may be a core feature of suicidality. Other risk factors that may partially mediate the PE-suicidal behavior association include poorer coping skills,57 stronger affective reactions to stress,58 more mood instability,43 more isolation and loneliness59,60 lower self-esteem,37 and higher rates of adverse childhood experiences, such as physical abuse, sexual abuse, and bullying in individuals with PEs 24,31,37,61,62 (Figure 2).

Strengths

A notable strength of the review is that we used longitudinal studies, which established a temporal association between PEs and suicidal behavior. All 10 studies were consistent in demonstrating an increased risk. What is more, the findings were consistent in demonstrating increased (albeit varying) levels of risk across a wide variety of countries, including in Africa, Asia, Europe, the Middle East, North America, and South America, suggesting that the association is not culture-specific.

Limitations

Previous research has suggested that suicidal ideation in the absence of suicide attempts (ie, isolated suicidal ideation) may not be associated with PEs—that is, it may be the case that only more severe forms of suicidal behavior, such as attempted and completed suicide, are associated with PEs.10,14 We were unable to look at isolated suicidal ideation in the current study, because some individuals who reported suicidal ideation may also have had a suicide attempt and we were unable to identify these individuals. This may have resulted in an overestimate of the effect size of the association between PEs and suicidal ideation outside of the context of more serious suicidal behavior. While participants in the included studies ranged in age from 11 to 65 years, most of the studies involved adolescents and young adults; we were also unable to look at specific age groups within the studies. Future research should investigate the association between PEs and suicidal behavior in later adulthood specifically. In addition, only 1 study looked specifically at suicide death; further research on PEs and suicide deaths will be valuable. Finally, this review only included articles written in the English language.

Conclusions

Psychotic experiences are a clinical marker of risk for future suicidal behavior, predicting a 2-fold increased odds of subsequent suicidal ideation (5 articles), a 3-fold increased odds of suicide attempt (8 articles) and a 4-fold increased odds of suicide death (1 article). Assessment of PEs (and not just symptoms of a fully psychotic individual) should form an important part of any mental state examination. Our findings suggest that there is a psychosis-associated subtype of suicidal behavior that extends well beyond the previously established association between psychotic disorder and suicidal behavior. Further research is necessary to understand whether specific types of PEs (for example, perceptual abnormalities vs unusual thought content) are more closely associated with suicidal behavior, whether suicidal behavior is a risk factor for later PEs (in addition to PEs being a risk marker for later suicidal behavior), and the interplay between the many potential mechanisms that contribute to the PE-suicidality association.

eTable. Appraisal of methodological quality (Newcastle–Ottawa Scale)

eFigure 1. Funnel plots for publication bias

eFigure 2. Bubbleplot showing the association between psychotic experiences and suicidality over time

References

- 1.Linscott RJ, van Os J. An updated and conservative systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological evidence on psychotic experiences in children and adults: on the pathway from proneness to persistence to dimensional expression across mental disorders. Psychol Med. 2013;43(6):1133-1149. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poulton R, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Cannon M, Murray R, Harrington H. Children’s self-reported psychotic symptoms and adult schizophreniform disorder: a 15-year longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(11):1053-1058. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.11.1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Werbeloff N, Drukker M, Dohrenwend BP, et al. Self-reported attenuated psychotic symptoms as forerunners of severe mental disorders later in life. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(5):467-475. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher HL, Schreier A, Zammit S, et al. Pathways between childhood victimization and psychosis-like symptoms in the ALSPAC birth cohort. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(5):1045-1055. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelleher I, Keeley H, Corcoran P, et al. Clinicopathological significance of psychotic experiences in non-psychotic young people: evidence from four population-based studies. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;201(1):26-32. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.101543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perlis RH, Uher R, Ostacher M, et al. Association between bipolar spectrum features and treatment outcomes in outpatients with major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(4):351-360. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wigman JTW, van Os J, Abidi L, et al. Subclinical psychotic experiences and bipolar spectrum features in depression: association with outcome of psychotherapy. Psychol Med. 2014;44(2):325-336. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713000871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott J, Martin G, Welham J, et al. Psychopathology during childhood and adolescence predicts delusional-like experiences in adults: a 21-year birth cohort study. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(5):567-574. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08081182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGrath JJ, Saha S, Al-Hamzawi A, et al. The bidirectional associations between psychotic experiences and DSM-IV mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(10):997-1006. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15101293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeVylder JE, Lukens EP, Link BG, Lieberman JA. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among adults with psychotic experiences: data from the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(3):219-225. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Honings S, Drukker M, Groen R, van Os J. Psychotic experiences and risk of self-injurious behaviour in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2016;46(2):237-251. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cederlöf M, Kuja-Halkola R, Larsson H, et al. A longitudinal study of adolescent psychotic experiences and later development of substance use disorder and suicidal behavior. Schizophr Res. 2017;181:13-16. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.08.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Connell M, Betts K, McGrath JJ, et al. Hallucinations in adolescents and risk for mental disorders and suicidal behaviour in adulthood: prospective evidence from the MUSP birth cohort study. Schizophr Res. 2016;176(2-3):546-551. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelleher I, Corcoran P, Keeley H, et al. Psychotic symptoms and population risk for suicide attempt: a prospective cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(9):940-948. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coory MD. Comment on: heterogeneity in meta-analysis should be expected and appropriately quantified. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(3):932. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR. How a meta-analysis works In: Introduction to Meta-Analysis. New York, NY: Wiley Online Library; 2009:1-7. doi: 10.1002/9780470743386.ch1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JPT. Commentary: Heterogeneity in meta-analysis should be expected and appropriately quantified. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37(5):1158-1160. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wells G, Shea A, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch J, Losos M The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm. Published 2018. Accessed October 17, 2018.

- 20.Islam MM, Iqbal U, Walther B, et al. Benzodiazepine use and risk of dementia in the elderly population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology. 2016;47(3-4):181-191. doi: 10.1159/000454881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharmin S, Kypri K, Khanam M, et al. Effects of parental alcohol rules on risky drinking and related problems in adolescence: systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;178:243-256. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharmin S, Kypri K, Khanam M, Wadolowski M, Bruno R, Mattick RP. Parental supply of alcohol in childhood and risky drinking in adolescence: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(3):E287. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14030287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelleher I, Lynch F, Harley M, et al. Psychotic symptoms in adolescence index risk for suicidal behavior: findings from 2 population-based case-control clinical interview studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(12):1277-1283. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saha S, Scott JG, Johnston AK, et al. The association between delusional-like experiences and suicidal thoughts and behaviour. Schizophr Res. 2011;132(2-3):197-202. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Honings S, Drukker M, van Nierop M, et al. Psychotic experiences and incident suicidal ideation and behaviour: disentangling the longitudinal associations from connected psychopathology. Psychiatry Res. 2016;245:267-275. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sullivan SA, Lewis G, Gunnell D, Cannon M, Mars B, Zammit S. The longitudinal association between psychotic experiences, depression and suicidal behaviour in a population sample of adolescents. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50(12):1809-1817. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1086-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin G, Thomas H, Andrews T, Hasking P, Scott JG. Psychotic experiences and psychological distress predict contemporaneous and future non-suicidal self-injury and suicide attempts in a sample of Australian school-based adolescents. Psychol Med. 2015;45(2):429-437. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714001615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelleher I, Cederlöf M, Lichtenstein P. Psychotic experiences as a predictor of the natural course of suicidal ideation: a Swedish cohort study. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(2):184-188. doi: 10.1002/wps.20131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bromet EJ, Nock MK, Saha S, et al. ; World Health Organization World Mental Health Survey Collaborators . Association between psychotic experiences and subsequent suicidal thoughts and behaviors: a cross-national analysis from the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(11):1136-1144. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharifi V, Eaton WW, Wu LT, Roth KB, Burchett BM, Mojtabai R. Psychotic experiences and risk of death in the general population: 24-27 year follow-up of the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;207(1):30-36. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.143198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fisher HL, Caspi A, Poulton R, et al. Specificity of childhood psychotic symptoms for predicting schizophrenia by 38 years of age: a birth cohort study. Psychol Med. 2013;43(10):2077-2086. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712003091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sterne JAC, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JPA, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d4002. http://www.bmj.com/content/343/bmj.d4002. abstract. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson SG, Higgins JPT. How should meta-regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted? Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1559-1573. doi: 10.1002/sim.1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allebeck P. Schizophrenia: a life-shortening disease. Schizophr Bull. 1989;15(1):81-89. doi: 10.1093/schbul/15.1.81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hielscher E, DeVylder JE, Saha S, Connell M, Scott JG. Why are psychotic experiences associated with self-injurious thoughts and behaviours? a systematic review and critical appraisal of potential confounding and mediating factors. Psychol Med. 2018;48(9):1410-1426. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717002677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kelleher I, Wigman JTW, Harley M, et al. Psychotic experiences in the population: association with functioning and mental distress. Schizophr Res. 2015;165(1):9-14. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DeVylder JE, Jahn DR, Doherty T, et al. Social and psychological contributions to the co-occurrence of sub-threshold psychotic experiences and suicidal behavior. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50(12):1819-1830. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1139-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kelleher I, Devlin N, Wigman JTW, et al. Psychotic experiences in a mental health clinic sample: implications for suicidality, multimorbidity and functioning. Psychol Med. 2014;44(8):1615-1624. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713002122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DeVylder JE, Burnette D, Yang LH. Co-occurrence of psychotic experiences and common mental health conditions across four racially and ethnically diverse population samples. Psychol Med. 2014;44(16):3503-3513. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bhavsar V, Maccabe JH, Hatch SL, Hotopf M, Boydell J, McGuire P. Subclinical psychotic experiences and subsequent contact with mental health services. BJPsych Open. 2017;3(2):64-70. doi: 10.1192/bjpo.bp.117.004689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kelleher I, Ramsay H, DeVylder J. Psychotic experiences and suicide attempt risk in common mental disorders and borderline personality disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;135(3):212-218. doi: 10.1111/acps.12693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jang JH, Lee YJ, Cho S-J, Cho IH, Shin NY, Kim SJ. Psychotic-like experiences and their relationship to suicidal ideation in adolescents. Psychiatry Res. 2014;215(3):641-645. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.12.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marwaha S, Broome MR, Bebbington PE, Kuipers E, Freeman D. Mood instability and psychosis: analyses of British national survey data. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(2):269-277. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cederlöf M, Ostberg P, Pettersson E, et al. Language and mathematical problems as precursors of psychotic-like experiences and juvenile mania symptoms. Psychol Med. 2014;44(6):1293-1302. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713002018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sullivan SA, Hollen L, Wren Y, Thompson AD, Lewis G, Zammit S. A longitudinal investigation of childhood communication ability and adolescent psychotic experiences in a community sample. Schizophr Res. 2016;173(1-2):54-61. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pollock LR, Williams JMG. Problem-solving in suicide attempters. Psychol Med. 2004;34(1):163-167. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703008092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blanchard MM, Jacobson S, Clarke MC, et al. Language, motor and speed of processing deficits in adolescents with subclinical psychotic symptoms. Schizophr Res. 2010;123(1):71-76. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kelleher I, Clarke MC, Rawdon C, Murphy J, Cannon M. Neurocognition in the extended psychosis phenotype: performance of a community sample of adolescents with psychotic symptoms on the MATRICS neurocognitive battery. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(5):1018-1026. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barnett JH, McDougall F, Xu MK, Croudace TJ, Richards M, Jones PB. Childhood cognitive function and adult psychopathology: associations with psychotic and non-psychotic symptoms in the general population. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;201(2):124-130. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.102053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O’Hanlon E, Leemans A, Kelleher I, et al. White matter differences among adolescents reporting psychotic experiences: a population-based diffusion magnetic resonance imaging study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(7):668-677. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jacobson McEwen SC, Connolly CG, Kelly AMC, et al. Resting-state connectivity deficits associated with impaired inhibitory control in non-treatment-seeking adolescents with psychotic symptoms. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;129(2):134-142. doi: 10.1111/acps.12141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jacobson S, Kelleher I, Harley M, et al. Structural and functional brain correlates of subclinical psychotic symptoms in 11-13 year old schoolchildren. Neuroimage. 2010;49(2):1875-1885. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pain O, Dudbridge F, Cardno AG, et al. Genome-wide analysis of adolescent psychotic-like experiences shows genetic overlap with psychiatric disorders. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2018;177(4):416-425. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Le-Niculescu H, Levey DF, Ayalew M, et al. Discovery and validation of blood biomarkers for suicidality. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(12):1249-1264. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Niculescu AB, Levey DF, Phalen PL, et al. Understanding and predicting suicidality using a combined genomic and clinical risk assessment approach. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20(11):1266-1285. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Levey DF, Niculescu EM, Le-Niculescu H, et al. Towards understanding and predicting suicidality in women: biomarkers and clinical risk assessment. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(6):768-785. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lin A, Wigman JTW, Nelson B, et al. The relationship between coping and subclinical psychotic experiences in adolescents from the general population—a longitudinal study. Psychol Med. 2011;41(12):2535-2546. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711000560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lataster T, Wichers M, Jacobs N, et al. Does reactivity to stress cosegregate with subclinical psychosis? a general population twin study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;119(1):45-53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01263.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lim MH, Gleeson JF. Social connectedness across the psychosis spectrum: current issues and future directions for interventions in loneliness. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:154. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Boyda D, McFeeters D, Shevlin M. Intimate partner violence, sexual abuse, and the mediating role of loneliness on psychosis. Psychosis. 2015;7(1):1-13. doi: 10.1080/17522439.2014.917433 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bebbington PE, Bhugra D, Brugha T, et al. Psychosis, victimisation and childhood disadvantage: evidence from the second British National Survey of Psychiatric Morbidity. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:220-226. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.3.220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arseneault L, Cannon M, Fisher HL, Polanczyk G, Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Childhood trauma and children’s emerging psychotic symptoms: a genetically sensitive longitudinal cohort study. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(1):65-72. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10040567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Appraisal of methodological quality (Newcastle–Ottawa Scale)

eFigure 1. Funnel plots for publication bias

eFigure 2. Bubbleplot showing the association between psychotic experiences and suicidality over time