Abstract

Objective

To investigate the factors to predict Gleason score upgrading (GSU) of patients with prostate cancer who were evaluated by using the International Society for Urological Pathology (ISUP) 2014 Gleason grading system.

Material and methods

Between January 2008 and December 2015, we retrospectively investigated patients who had undergone radical prostatectomy and followed up in the uro-oncology outpatient clinic. The pathologic specimens of the patients were evaluated based on the ISUP 2014 classification system. The patients were divided into two groups with or without upgraded Gleason scores. Factors that could be effective in predicting upgrading such as age, prostate-specific antigen (PSA), prostate volume, D’Amico risk classification, PSA density, cancer of the prostate risk assessment (CAPRA) scores, biopsy tumor percentage, body mass index, and clinical stage parameters were compared between both groups.

Results

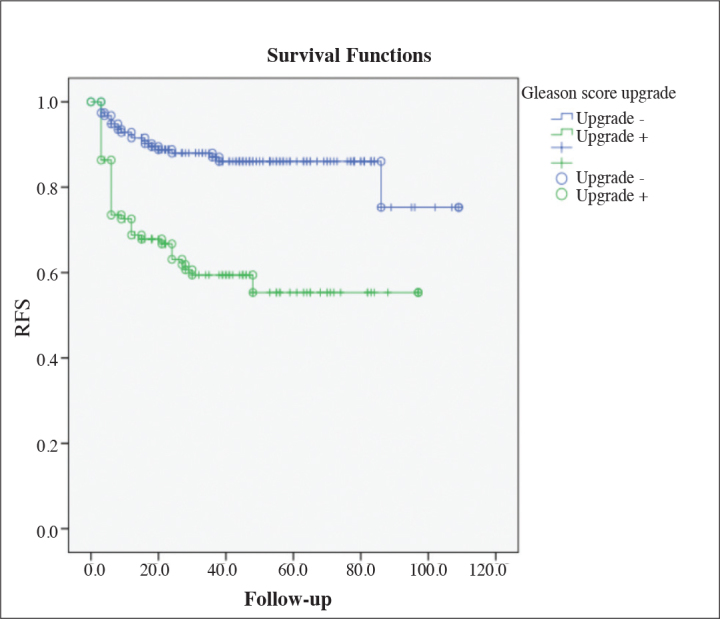

Of the 265 patients who could be evaluated and followed up regularly, Gleason score upgrades were observed in 110 (41.5%) patients. Advanced age (p=0.009), PSA >20 ng/mL (p=0.036), PSA density >0.35 (p=0.005), high CAPRA score (p=0.031), and high biopsy tumor percentage (p=0.009) were discovered to be correlated with Gleason score upgrade in univariate logistic regression analysis. Advanced age alone was a predictor for GSU in multivariate logistic regression analysis (p=0.002). Five-year biochemical recurrence-free survival rate was 86% in the non-GSU group and 55% in the GSU group (p<0.001).

Conclusion

GSU risk should be taken into consideration in making therapeutic decisions for older patients with prostate cancer, and precautions should be taken against development of aggressive disease.

Keywords: Gleason score, prostate biopsy, prostate cancer, radical prostatectomy

Introduction

Prostate cancer, one of the common cancer types, is one of the frequent reasons for cancer deaths.[1] The Gleason score is used for the histologic grading of prostate cancer, and it is one of the important markers in making treatment decisions.[2] The Gleason grading system was first defined in 1966 and updated in subsequent years, its last update being in 2014 by the International Society for Urological Pathology (ISUP).[3,4] There is a compliance problem between Gleason scores estimated for transrectal prostate biopsy and radical prostatectomy specimens up to 50% in the literature.[5,6] Having such different results for a parameter that is quite influential in therapeutic decision making creates a need for other markers in choosing the ideal treatment. Especially, it is difficult and risky to decide active surveillance.

We aimed to investigate factors that affected Gleason score upgrading (GSU) of the patients with prostate cancer who were evaluated using the World Health Organization (WHO)/ISUP 2014 Gleason grading system.

Material and methods

Between January 2008 and December 2015, we retrospectively investigated patients who were under regularly surveillance in the uro-oncology outpatient clinic for at least one year after undergoing radical prostatectomy in Istanbul Medeniyet University Göztepe Training and Research Hospital. Ethics committee approval (2017/0336) was granted for collecting and analyzing data in our radical prostatectomy database. The pathological specimens of the patients were evaluated once more by the same experienced pathologist (BG) based on the WHO/ISUP 2014 classification system, and tumors were divided into 5 groups as follows: (Group 1: Gleason score 3+3=6/10; Group 2: Gleason score 3+4=7/10; Group 3: Gleason score 4+3=7/10; Group 4: Gleason total score 8 and Group 5: Gleason total score 9–10).

The patients were divided into two groups as those whose Gleason scores were upgraded (GSU) or not (Non-GSU) after comparing their biopsy and radical prostatectomy specimen Gleason scores. Preoperative and postoperative clinical characteristics and oncological follow-up results of the patients were recorded. Factors that could be effective in predicting GSU such as age, prostate-specific antigen (PSA), prostate volume, D’Amico risk classification, cancer of the prostate risk assessment (CAPRA) scores, biopsy tumor percentage, body mass index (BMI), and clinical stage parameters were compared between both groups.

During follow-up period, having at least two PSA values >0.2 ng/mL was considered as biochemical recurrence. Both groups were compared in terms of biochemical recurrence-free survival rates.

Statistical analysis

Parameters affecting GSU were analyzed using Student’s t-test, Mann-Whitney U test, chi-square, and the multivariate logistic regression test in statistical analysis. Kaplan-Meier survival curve (log-rank) analysis was used to evaluate biochemical recurrence. The p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 21 (IBM SPSS Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Of the 265 patients who could be evaluated and followed up regularly, median age of the patients was 63.1 years (range, 44–76 years), median PSA (13 ng/mL: range, 2–125 ng/mL), BMI (27.2 kg/m2) values and follow-up time (46.08 months: range, 12–110 months) were as indicated (Table 1). Gleason score upgrades were observed in 110 (41.5%) patients. A total of 22 patients had extraprostatic spread, and 13 patients had seminal vesicle invasion. Higher ISUP grades were estimated for radical prostatectomy specimens in respective number of patients in Groups 1 (n=97), 2 (n=72), 3 (n=33), 4 (n=29), and 5 (n=34). During the follow-up period 65 (24.5%) patients in the whole series had biochemical recurrence.

Table 1.

Clinical and histopathological predictive factors of all patients

| n=265 | |

|---|---|

| Age (year) | 63.14±6.5 (44–76) |

|

| |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.28±3.51 (17.9–42.51) |

|

| |

| Prostate volume (cc) | 42.68±20.82 (10–129) |

|

| |

| PSA (ng/mL) | 13±16.45 (2–125) |

|

| |

| CAPRA score | |

| Low (0–2) | 121 (45.6%) |

| Moderate (3–5) | 107 (40.4%) |

| High (6–10) | 37 (14%) |

|

| |

| Mean follow-up time (mo) | 46.08±23.84 (12–110) |

|

| |

| Trus-Bx ISUP 2014 | |

| 1 | 149 (56.2%) |

| 2 | 57 (21.5%) |

| 3 | 18 (6.8%) |

| 4 | 27 (10.2%) |

| 5 | 14 (5.3%) |

|

| |

| Pathologic stage | |

| T2a | 47 (30.3%) |

| T2b | 13 (8.4%) |

| T2c | 58 (37.4%) |

| T3a | 22 (14.2%) |

| T3b | 13 (8.4%) |

| T4 | 2 (1.3%) |

|

| |

| Biochemical recurrence | 65 (24.5%) |

|

| |

| RRP ISUP 2014 | |

| 1 | 97 (36.6%) |

| 2 | 72 (27.2%) |

| 3 | 33 (12.5%) |

| 4 | 29 (10.9%) |

| 5 | 34 (12.8%) |

|

| |

| RRP tumor rate | 35.48±26.32 |

|

| |

| pN Positive | 12/90 (13.3%) |

BMI: body mass index; PSA: prostate-specific antigen; CAPRA score: cancer of the prostate risk assessment score; RRP: radical retropubic prostatectomy; pN Positive: pathologic node positive

Advanced age (p=0.009), PSA >20 ng/mL (p=0.036), PSA density >0.35 (p=0.005), high CAPRA score (p=0.031), and high biopsy tumor percentage (p=0.009) were discovered to be correlated with Gleason score upgrade in univariate logistic regression analysis. However, GSU had no correlation with clinical stage, prostate volume, BMI, and D’Amico risk classification (p>0.05). However, advanced age alone was a predictor for GSU in multivariate logistic regression analysis (p=0.002) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Analysis of factors that affect Gleason score upgrading

| No upgrade in Gleason score + decrease (n=155) | Upgrade in Gleason score (n=110) | Univariate p | Multivariate analysis (Logistic regression) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| <60 | 48 (31%) | 22 (20%) | 0.009* | 0.002* |

| 60–70 | 86 (55.5%) | 58 (52.7%) | ||

| >70 | 21 (13.5%) | 30 (27.3%) | ||

|

| ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| 18.5–24.9 | 43 (27.7%) | 37 (33.6%) | 0.564 | 0.600 |

| 25–29.9 | 82 (52.9%) | 52 (47.3%) | ||

| >30 | 30 (19.4%) | 21 (19.1%) | ||

|

| ||||

| Prostate volume (cc) | 52 (33.5%) | 36 (32.7%) | 0.569 | 0.227 |

| <30 | 72 (46.5%) | 57 (51.8%) | ||

| 30–60 | 31 (20%) | 17 (15.5%) | ||

| >60 | ||||

|

| ||||

| D’Amico risk group | ||||

| Low | 71 (45.8%) | 38 (34.5%) | 0.183 | 0.067 |

| Moderate | 52 (33.5%) | 45 (40.9%) | ||

| High | 32 (20.6%) | 27 (24.5%) | ||

|

| ||||

| Total PSA (ng/mL) | ||||

| 0.1–10 | 107 (69%) | 60 (54.5%) | 0.036* | 0.363 |

| 10.1–20 | 34 (21.9%) | 31 (28.2%) | ||

| >20 | 14 (9%) | 19 (17.3%) | ||

|

| ||||

| PSA density | ||||

| <0.35 | 118 (76%) | 66 (60%) | 0.005* | 0.323 |

| >0.35 | 37 (24%) | 44 (40%) | ||

|

| ||||

| CAPRA score | ||||

| 0–2 low | 80 (51.6%) | 41 (37.3%) | 0.031* | 0.243 |

| 3–5 average | 59 (38.1%) | 48 (43.6%) | ||

| 6–10 high | 16 (10.3%) | 21 (19.1%) | ||

|

| ||||

| TRUS-biopsy tumor percentage | 23.85±20.22 | 30.93±23.38 | 0.009* | 0.234 |

|

| ||||

| Clinical stage | ||||

| T1c | 89 (57.4%) | 51 (46.4%) | 0.180 | 0.828 |

| T2 | 62 (40%) | 54 (49.1%) | ||

| T3 | 4 (2.6%) | 5 (4.5%) | ||

BMI: body mass index; PSA: prostate specific antigen; CAPRA score: cancer of the prostate risk assessment score; TRUS: transrectal ultrasound

The five-year biochemical recurrence-free survival rate was 86% in the non-GSU group and 55% in the GSU group. There was a significant difference in the biochemical recurrence-free survival rates based on the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (log-rank p<0.001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Biochemical recurrence-free survival

Discussion

The Gleason score is a highly effective parameter in making therapeutic decisions for prostate cancer. Identifying the Gleason score correctly helps physicians to decide on various treatment options such as active monitoring, radical prostatectomy, radiotherapy or adjuvant/salvage androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) with curative treatment accurately. Owing to the WHO/ISUP 2014 decision, patients who scored low can later on have higher scores. Additionally, grade grouping provided a more convenient use. In this study, we reevaluated the Gleason scores and discovered upgrades in 41% of the patients. Similar to previous studies, advanced age was found to have a correlation with increased upgrade risk in the multivariate analysis.[6–9] Decisions should be made more carefully for advanced-age groups due to their comorbidities, and despite popular belief, these patients have a higher risk for an aggressive disease. Moreover, patients undergoing radiotherapy (RT) and also active surveillance groups whose final Gleason scores cannot be found should be watched closely in order to prevent emergence of poor oncologic results.

Accurate evaluation of biopsy Gleason scores matters a great deal for the nomograms that aim to determine patients’ pathologic stage in clinical practice.[10] Factors such as PSA, PSA density, prostate volume, BMI, CAPRA score, positive core percentage, low serum testosterone level, and prolonged time intervals between biopsy and surgery were found to be correlated with upgrades.[11–16] In our study, most of these factors were found to be effective in the univariate analysis but insignificant in the multivariate analysis. The reasoning behind this could be the fact that we used the new grading system.

In accordance with the literature, a relationship was detected between GSU and biochemical recurrence in the present study (p=0.001).[17,18] In a study by Santok et al.[19], the biochemical recurrence-free survival, cancer-specific survival, and overall survival rates were comparatively lower in patients who underwent robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP) and had Gleason score upgrading (p≤0.001, p=0.003, and p=0.01). In order to demonstrate the relationship between GSU and the disease progression, the long-term monitoring was needed in our study.

Standard transrectal prostate biopsies and randomized sampling could make it difficult to determine the Gleason score accurately for multifocal prostate cancer. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in prostate cancer allows the opportunity for disease staging and targeted biopsy.[20–22] Prostate biopsies performed with the aid of fusion-guided MRI/ultrasonography (US), detected 14.3% of prostate cancers that could not be detected using standard 12-core prostate biopsy. Diagnosis by using fusion biopsy, 86.7% of patients had clinically significant prostate cancer.[23] Lai et al.[24] reported that the results from MRI-targeted biopsies and findings from MRI could predict upgrade risk for patients with prostate cancer in the active surveillance group. Using MRI fusion biopsy, 26% of upgraded cases could be detected. The assumption that it is only possible to perform targeted biopsies from index lesions accurately and safely in special experienced centers based on the still-developing Prostate Imaging Reporting and Data System (PIRADS) classification precludes widespread use of MRI in the short term.

Genomic tests can provide valuable information on risks for radical prostatectomy performed after biochemical recurrence, metastasis, cancer-specific mortality or postoperative course of prostate cancer after RT.[25–28] Although genomic tests are included in current guidelines, there is still a need for a solution towards financial issues concerning its widespread clinical use.[29] Additionally, it was reported that the number of cancer-propagating cells found in prostate cancer (CPCs) correlated with GSU.[30] In order to provide patients with a safe and effective treatment plan, it would be ideal to acquire all final histopathological information. However, since the common choices in the current management of prostate cancer include options such as active surveillance and RT, current data will not be enough to overcome the problem of GSU. A model that combines MRI findings, genomic tests, and the patient’s clinical characteristics could maximize the consistency of Gleason score.

The limitations of the present study included the need for long-term monitorization to evaluate cancer-specific survival and metastasis. The study was designed to be a retrospective trial and, the patients whose MRI information was not available were not included in the study. There is a gap in the field for prospective studies concerning MRI findings and genomic profiles.

Advanced age can be accepted as a predictive factor for GSU and, GSU risk should be taken into consideration in making therapeutic decisions for older patients with prostate cancer, and precautions should be taken to prevent development of aggressive disease.

Footnotes

Ethics Committee Approval: Ethics committee approval was received for this study from the ethics committee of Istanbul Medeniyet University School of Medicine (2017/0336).

Informed Consent: Due to the retrospective design of the study, informed consent was not taken.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept - T.T., A.Y.; Design - T.T., A.Y.; Supervision - T.Ç., A.Y.; Resources - B.G., Ö.E.; Materials - B.G., G.A.; Data Collection and/or Processing - F.Ş., Ö.E.; Literature Search - F.Ş., G.A.; Writing Manuscript - T.T., Ö.E., A.Y.; Critical Review - T.T., B.G., Ö.E., F.Ş., G.A., T.Ç., A.Y.

Conflict of Interest: Authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Financial Disclosure: The authors have declared that they didn’t receive any financial support for the study.

References

- 1.Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Kramer JL, Rowland JH, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:271–89. doi: 10.3322/caac.21349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mottet N, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, Briers E, Cumberbatch MG, De Santis M, et al. EAU-ESTRO-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent. Eur Urol. 2017;71:618–29. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epstein JI, Egevad L, Amin MB, Delahunt B, Srigley JR, Humphrey PA, et al. The 2014 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) consensus conference on Gleason grading of prostatic carcinoma: definition of grading patterns and proposal for a new grading system. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:244–52. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Epstein JI, Zelefsky MJ, Sjoberg DD, Nelson JB, Egevad L, Magi-Galluzzi C, et al. A contemporary prostate cancer grading system: a validated alternative to the Gleason score. Eur Urol. 2016;69:428–35. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.06.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kvale R, Moller B, Wahlqvist R, Fossa SD, Berner A, Busch C, et al. Concordance between Gleason scores of needle biopsies and radical prostatectomy specimens: a population-based study. BJU Int. 2009;103:1647–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gershman B, Dahl DM, Olumi AF, Young RH, McDougal WS, Wu CL. Smaller prostate gland size and older age predict Gleason score upgrading. Urol Oncol Seminars and Original Investigations: 2013; Elsevier; 2013. pp. 1033–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caster JM, Falchook AD, Hendrix LH, Chen RC. Risk of pathologic upgrading or locally advanced disease in early prostate cancer patients based on biopsy Gleason score and PSA: a population-based study of modern patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;92:244–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herlemann A, Buchner A, Kretschmer A, Apfelbeck M, Stief CG, Gratzke C, et al. Postoperative upgrading of prostate cancer in men≥ 75 years: a propensity score-matched analysis. World J Urol. 2017;35:1517–24. doi: 10.1007/s00345-017-2045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang DD, Mahal BA, Muralidhar V, Nezolosky MD, Vastola ME, Labe SA, et al. Risk of Upgrading and Upstaging Among 10000 Patients with Gleason 3+ 4 Favorable Intermediate-risk Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol Focus. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2017.05.011. pii: S2405-4569(17)30148-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Partin AW, Mangold LA, Lamm DM, Walsh PC, Epstein JI, Pearson JD. Contemporary update of prostate cancer staging nomograms (Partin Tables) for the new millennium. Urology. 2001;58:843–8. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(01)01441-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies JD, Aghazadeh MA, Phillips S, Salem S, Chang SS, Clark PE, et al. Prostate size as a predictor of Gleason score upgrading in patients with low risk prostate cancer. J Urol. 2011;186:2221–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.07.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans SM, Bandarage VP, Kronborg C, Earnest A, Millar J, Clouston D. Gleason group concordance between biopsy and radical prostatectomy specimens: A cohort study from Prostate Cancer Outcome Registry-Victoria. Prostate Int. 2016;4:145–51. doi: 10.1016/j.prnil.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vora A, Large T, Aronica J, Haynes S, Harbin A, Marchalik D, et al. Predictors of Gleason score upgrading in a large African-American population. Int Urol Nephrol. 2013;45:1257–62. doi: 10.1007/s11255-013-0495-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sfoungaristos S, Perimenis P. Clinical and pathological variables that predict changes in tumour grade after radical prostatectomy in patients with prostate cancer. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7:E93. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferro M, Lucarelli G, Bruzzese D, Di Lorenzo G, Perdonà S, Autorino R, et al. Low serum total testosterone level as a predictor of upstaging and upgrading in low-risk prostate cancer patients meeting the inclusion criteria for active surveillance. Oncotarget. 2017;8:18424–34. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eroglu M, Doluoglu OG, Sarici H, Telli O, Ozgur BC, Bozkurt S. Does the time from biopsy to radical prostatectomy affect Gleason score upgrading in patients with clinical t1c prostate cancer? Korean J Urol. 2014;55:395–9. doi: 10.4111/kju.2014.55.6.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corcoran NM, Hong MK, Casey RG, Hurtado-Coll A, Peters J, Harewood L, et al. Upgrade in Gleason score between prostate biopsies and pathology following radical prostatectomy significantly impacts upon the risk of biochemical recurrence. BJU Int. 2011;108:E202–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boorjian SA, Karnes RJ, Crispen PL, Rangel LJ, Bergstralh EJ, Sebo TJ, et al. The impact of discordance between biopsy and pathological Gleason scores on survival after radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2009;181:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santok GDR, Abdel Raheem A, Kim LH, Chang K, Lum TG, Chung BH, et al. Prostate-specific antigen 10–20 ng/mL: A predictor of degree of upgrading to≥ 8 among patients with biopsy Gleason score 6. Investig Clin Urol. 2017;58:90–7. doi: 10.4111/icu.2017.58.2.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamauchi FI, Penzkofer T, Fedorov A, Fennessy FM, Chu R, Maier SE, et al. Prostate cancer discrimination in the peripheral zone with a reduced field-of-view T 2-mapping MRI sequence. Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;33:525–30. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Velez E, Fedorov A, Tuncali K, Olubiyi O, Allard CB, Kibel AS, et al. Pathologic correlation of transperineal in-bore 3-Tesla magnetic resonance imaging-guided prostate biopsy samples with radical prostatectomy specimen. Abdom Radiol. 2017;42:2154–9. doi: 10.1007/s00261-017-1102-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pessoa RR, Viana PC, Mattedi RL, Guglielmetti GB, Cordeiro MD, Coelho RF, et al. Value of 3-Tesla multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging and targeted biopsy for improved risk stratification in patients considered for active surveillance. BJU Int. 2017;119:535–42. doi: 10.1111/bju.13624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rastinehad AR, Turkbey B, Salami SS, Yaskiv O, George AK, Fakhoury M, et al. Improving detection of clinically significant prostate cancer: magnetic resonance imaging/transrectal ultrasound fusion guided prostate biopsy. J Urol. 2014;191:1749–54. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lai WS, Gordetsky JB, Thomas JV, Nix JW, Rais-Bahrami S. Factors predicting prostate cancer upgrading on magnetic resonance imaging-targeted biopsy in an active surveillance population. Cancer. 2017;123:1941–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nguyen PL, Haddad Z, Lam LL, Ong K, Buerki C, Deheshi S, et al. Evaluation of the Decipher prostate cancer classifier to predict metastasis and disease-specific mortality from genomic analysis of diagnostic prostate needle biopsy specimens. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(Suppl 6):4. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao SG, Chang SL, Spratt DE, Erho N, Yu M, Ashab HAD, et al. Development and validation of a 24-gene predictor of response to postoperative radiotherapy in prostate cancer: a matched, retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1612–20. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30491-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ross AE, Johnson MH, Yousefi K, Davicioni E, Netto GJ, Marchionni L, et al. Tissue-based genomics augments post-prostatectomy risk stratification in a natural history cohort of intermediate-and high-risk men. Eur Urol. 2016;69:157–65. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cooperberg MR, Brand TC, Simko J, Sesterhenn I, Zhang N, Crager M, et al. Patient-specific meta-analysis (MA) of two validation studies to predict pathologic outcomes in prostate cancer (PCa) using a 17-gene genomic prostate score (GPS) J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(Suppl 2):100. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohler JL, Armstrong AJ, Bahnson RR, D’Amico AV, Davis BJ, Eastham JA, et al. Prostate cancer, version 1.2016. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14:19–30. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murray NP, Reyes E, Fuentealba C, Aedo S, Jacob O. The presence of primary circulating prostate cells is associated with upgrading and upstaging in patients eligible for active surveillance. Ecancermedicalscience. 2017;11:711. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2017.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]