Abstract

West Nile virus (WNV) is the most frequent mosquito-borne disease reported in the continental United States and although an effective veterinary vaccine exists for horses, there is still no commercial vaccine approved for human use. We have previously tested a 3% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)-based WNV inactivation approach termed, HydroVax, in Phase I clinical trials and the vaccine was found to be safe and modestly immunogenic. Here, we describe an advanced, next-generation oxidation approach (HydroVax-II) for the development of inactivated vaccines that utilizes reduced concentrations of H2O2 in combination with copper (cupric ions, Cu2+) complexed with the antiviral compound, methisazone (MZ). Further enhancement of this oxidative approach included the addition of a low percentage of formaldehyde, a cross-linking reagent with a different mechanism of action that, together with H2O2/Cu/MZ, provides a robust two-pronged approach to virus inactivation. Together, this new approach results in rapid virus inactivation while greatly improving the maintenance of WNV-specific neutralizing epitopes mapped across the three structural domains of the WNV envelope protein. In combination with more refined manufacturing techniques, this inactivation technology resulted in vaccine-mediated WNV-specific neutralizing antibody responses that were 130-fold higher than that observed using the first generation, H2O2-only vaccine approach and provided 100% protection against lethal WNV infection. This new approach to vaccine development represents an important area for future investigation with the potential not only for improving vaccines against WNV, but other clinically relevant viruses as well.

Keywords: West Nile virus, hydrogen peroxide, advanced oxidation, vaccine, vaccination, antibody

1. Introduction

Inactivated or replication-deficient whole virus particle vaccines represent approximately one-third of currently licensed vaccines [1]. Inactivation approaches or technologies may vary by virus, but most of the licensed vaccines that incorporate an inactivation step during the manufacturing process are limited to formaldehyde, beta-propiolactone (BPL) or ultraviolet (UV) irradiation [2]. While these methodologies have led to the successful development of important and life-saving vaccines, several failures have also been documented. For example, vaccination with either formaldehyde-inactivated respiratory syncytial virus (FIRSV) or formaldehyde-inactivated measles virus (FIMV) resulted in loss of protective immunity and enhanced disease following exposure to their respective viral pathogens, with formaldehyde-induced damage of key antigenic epitopes implicated in both instances [3]. A major factor that may contribute to these results is that formaldehyde-based inactivation is not linear and the “tailing” effect of progressively slower inactivation kinetics [4] is typically compensated by increasing the exposure time to several weeks or months in order to achieve sufficient levels of inactivation suitable for clinical vaccine production. Antigenic damage during virus inactivation is a common challenge and has also been shown in other virus models as well, such as the hemagglutinin (HA) protein of influenza [5–7]. Early studies comparing formaldehyde, BPL, and UV irradiation demonstrated the potential for these reagents to damage influenza HA activity and limit in vivo immunogenicity [5]. More recent studies have confirmed these results, with evidence of substantial HA damage induced by formaldehyde, BPL, or UV treatment [6, 7]. Maintaining the structural integrity and neutralizing epitopes of viral surface antigens is key to eliciting protective humoral immune responses and a better understanding of these parameters could aid in the development of new and improved vaccines against a number of human pathogens.

Until the recent description of a H2O2-based platform for the development of improved whole-virus vaccines [8–11], alternative approaches to virus inactivation have been limited. One of the first pathogens targeted with this H2O2-based technology was West Nile virus (WNV) [8–10]. Preclinical studies demonstrated that H2O2-inactivated WNV vaccines elicited robust neutralizing antibody responses in both young and aged mice, with significant antibody-mediated and CD8+ T cell-mediated protection against lethal challenge [8–10]. Clinical-grade vaccine material, manufactured in compliance with current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP), was produced and found to be safe and immunogenic in three animal species, including mice, Sprague-Dawley rats, and non-human primates (NHP) [10]. Based on these preclinical results, a Phase I trial of this vaccine, termed HydroVax-001 WNV, was performed (clinicaltrials.gov: NCT02337868) [12]. While results indicated a good safety profile, immunogenicity was modest and similar to the limited WNV vaccine-induced antibody responses observed in other clinical trials [13]. To address these limitations, we developed further improvements to the HydroVax vaccine platform, which incorporates advanced, site-directed oxidation technologies. A vaccine candidate using updated manufacturing techniques and this advanced inactivation approach resulted in greatly improved WNV-specific neutralizing antibody levels, with peak titers reaching >100-fold higher than that observed using the original 3% H2O2-based inactivation methodology. These studies indicate that the advanced oxidation approach to WNV vaccine development described here could improve upon these earlier preliminary clinical results and provide a path forward towards a safe and potentially more immunogenic WNV vaccine in humans.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells, virus stocks and inactivation studies

The Vero cells and WNV strains used in these studies have been previously described in detail [10]. The naturally attenuated, lineage 1 Kunjin virus isolate (WNV-KV, isolate CH16532) was used for vaccine production, while the virulent New York 1999 strain (WNV-NY99) was utilized for in vivo challenge studies. WNV-KV is a Biosafety Level 2 (BSL2) virus, which allows feasibility for routine manufacturing while still retaining the capacity to induce broad neutralizing antibody responses across a range of circulating Lineage I and Lineage II WNV strains [10]. Virus inactivation kinetics were performed as previously described [9]. To confirm complete inactivation prior to in vivo use, at least 5% of each vaccine lot was tested using a residual live virus assay [10].

2.2. Vaccines

The original HydroVax-based WNV vaccine (termed, HydroVax, in this study) was concentrated/purified using tangential flow filtration (TFF), inactivated with 3% H2O2 for 7 hours at room temperature with a mid-stage 0.2 μm filtration step to remove any potential aggregates, and purified by ion-exchange chromatography (Cellufine sulfate; JNC America, Rye, NY) to remove residual H2O2 as previously described [10]. The HydroVax-II vaccine approach utilized the same TFF-concentrated/purified lot of WNV but also included CaptoCore™ 700 chromatography (GE Life Sciences) prior to inactivation as an additional upstream purification step (Supplemental Figure 1), and an advanced oxidation approach for inactivation. For this advanced inactivation process, purified WNV was treated with 20 μM of methisazone (Key Organics, Camelford, United Kingdom), 0.125 μM of CuCl2 (Sigma Aldrich), and 0.005% H2O2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in a proprietary high phosphate buffer containing 0.019% formaldehyde. This concentration of formaldehyde is too slow to use on its own in the timeframe permitted (WNV inactivation T1/2 = 24 minutes) but was added as a protein stabilizer ([14–16] and data not shown). Virus inactivation was allowed to proceed for 20 hours at room temperature with a mid-stage 0.2 μm filtration step to remove any potential aggregates, followed by Cellufine sulfate ion-exchange chromatography to remove residual inactivation reagents. Both HydroVax and HydroVax-II vaccine candidates were formulated with 0.1% aluminum hydroxide (Alhydrogel®; Brenntag Biosector, Denmark).

2.3. WNV ELISA and neutralization assays

Epitope mapping of WNV-KV vaccine candidates was performed using WNV envelope (Env)-specific monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) generously provided by Dr. Michael Diamond or BEI Resources and assayed as detailed previously [10] with the exception that we used the humanized MAb, MGAWN1, that has the same epitope specificity as mouse MAb E16. Briefly, inactivated or live control WNV antigens were used to coat ELISA plates (Polystyrene High Bind, Corning) overnight at 2–8°C at 1 μg/mL. Unbound antigen was removed and plates were treated with blocking buffer (5% non-fat dry milk in PBS-T [PBS supplemented with 0.05% Tween-20]) for 1 hr at room temperature. Plates were rinsed 1X with PBS-T and incubated for 1 hour with serial dilutions of each WNV-specific antibody. Plates were washed 3X with PBS-T and incubated with an optimal dilution of either goat anti-mouse IgG(γ)-HRP antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, for MAbs E18, E24, E48, E53, E60, E100, E113 and E121) or mouse anti-human IgG(γ)-HRP antibody (BD Pharmingen, for MAb MGAWN1) for 1 hr at RT. After a final wash, plates were developed with o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (OPD) substrate in citrate buffer for 20 minutes, with development stopped by the addition of an equal volume of 1M HCl, and optical densities (OD) were measured at 490 nm. Blank-subtracted ODs were plotted versus antibody concentration and analyzed using non-linear regression (Prism 7, GraphPad Software) to determine the maximum ELISA titer (Bmax) for each condition. The percentage of the live virus signal was calculated for each inactivation condition by comparison to the matched live control ELISA result (Figure 2). Serum neutralization titers (NT50) for WNV-KV were assessed using a focus-forming assay (FFA) as described [10].

Figure 2. Virus inactivation with HydroVax-II technology improves the retention of neutralizing WNV-specific epitopes during inactivation.

(A) Purified WNV-KV was treated with 3% H2O2 for 7 hours (HydroVax), or treated with HydroVax-II for 20 hours at room temperature. Inactivated virus was diluted, coated onto ELISA plates and assayed with a panel of WNV Env-specific MAbs to determine the structural integrity of neutralizing epitopes among different regions of the WNV Env protein. The positive control (Live) consisted of untreated live WNV incubated under the same conditions for 20 hours in the absence of inactivation reagents. (B) The maximum ELISA titer was established for each MAb based on the live virus controls and the percentage of the live virus signal was calculated for each inactivation condition. DI-lr, Domain I lateral ridge; DII-ci, Domain II central interface; DII-di, Domain II dimer interface; DII-hi, Domain II hinge interface; DII-fl, Domain II fusion loop. MGAWN1 is a humanized version of the E16 antibody and retains the same epitope specificity [45].

2.4. Animal studies

Female BALB/c mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), and used at 13 weeks of age. Following a 2-dose intraperitoneal vaccination series using 1 μg/dose at day 0 and day 28, mice were challenged via the intraperitoneal (i.p.) route with WNV-NY99 (200 PFU, 20 LD50) at 2 months after booster vaccination (3 months after primary vaccination) as previously described [8]. Mice that became moribund or experienced greater than 25% weight loss were humanely euthanized according to protocol. All mouse studies were overseen and approved by the OHSU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guide for the care and use of laboratory animals.

3. Results

3.1. Advanced approaches to virus inactivation

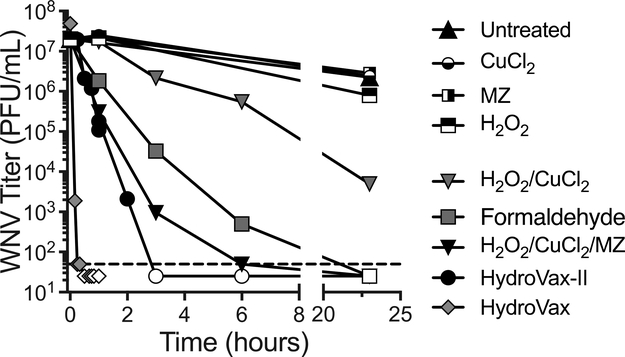

Prior studies have shown that prolonged exposure to formaldehyde or H2O2 can damage surface epitopes of flaviviruses such as yellow fever virus (YFV) [8] or WNV [10], particularly the neutralizing epitopes in domains I and II of the WNV Env protein. To investigate potential improvements in virus inactivation, we explored the use of Fenton-type chemistry to further refine the H2O2-based inactivation system (Figure 1). In Fenton-type chemical reactions, ions of redox-active transition metals such as iron (Fe) or copper (Cu) act as a catalyst that can interact with H2O2 to produce hydroxyl radicals [17]. Cu has been shown to greatly increase the rate of H2O2-induced nucleic acid degradation [18], likely through a site-specific mechanism where nucleic acid-bound Cu interacts with H2O2 to potentiate localized oxidation [19]. Preliminary studies demonstrated that Cu2+ (in the form of CuCl2) could efficiently enhance virus inactivation using lower H2O2 concentrations, but still resulted in some damage to neutralizing epitopes (data not shown). To further increase the specificity of inactivation, we searched for reagents known to interact with Cu that could potentially target the Cu molecules to viral nucleic acids, thereby focusing peroxide-induced damage to the viral genome and thus more efficiently inactivate the pathogen while leaving protein epitopes intact. We identified a suitable candidate, methisazone (MZ), an antiviral drug developed in the 1950s to treat or prevent smallpox during outbreaks [20]. MZ binds Cu [21] and complexes of MZ with copper (MZ-Cu) have been shown to bind nucleic acids, including single-stranded DNA, double-stranded DNA, or single-stranded RNA molecules [22]. Based on pilot optimization studies, we developed a lead inactivation formulation containing 20 μM of methisazone, 0.125 μM of CuCl2, and 0.005% (1630 μM) H2O2. At these concentrations, none of these three individual components had a substantial impact on infectious virus titers, even after 20 hours of exposure (Figure 1). In contrast, the combination of H2O2/CuCl2 (i.e., a Fenton-type reaction) was measurably virucidal but showed an inactivation half-life of only T1/2 = 119 minutes. Addition of MZ to this mixture (H2O2/CuCl2/MZ) increased inactivation rates by nearly 600%, resulting in T1/2 = 19.9 minutes. Inactivation of WNV with 0.019% formaldehyde alone resulted in T1/2 = 23.8 minutes and residual live virus could still be detected at 6 hours post-inactivation. However, when the H2O2/CuCl2/MZ formulation was combined with formaldehyde, the speed of inactivation increased sharply, resulting in T1/2 = 8.8 minutes and the loss of detectable live virus was observed within 3 hours post-inactivation. Inactivation of WNV with 3% H2O2 results in rapid virus inactivation with T1/2 = 1–2.5 minutes (Figure 1 and [10]). Although the HydroVax-II approach had slower inactivation kinetics than the original HydroVax (3% H2O2) approach, both formulations result in a theoretical loss of >40 Log10 of infectious virus, representing a substantial degree of excess inactivation since WNV was inactivated at a starting concentration of ~8 Log10 PFU/mL.

Figure 1. The HydroVax-II inactivation approach provides robust inactivation of WNV.

Inactivation kinetics were performed with purified WNV-KV using the indicated individual chemicals and combinations of inactivation reagents. HydroVax consisted of 3% H2O2, whereas HydroVax-II consisted of an optimized combination of 0.005% H2O2, 0.125 μM CuCl2, 20 μM methisazone (MZ) and 0.019% formaldehyde. The list of individual reagents and reagent combinations were tested at the same concentrations used in the final optimized HydroVax-II inactivation approach. The dashed line indicates the limit of detection (50 PFU/mL) and open symbols represent data points in which no infectious virus was identified.

3.2. Retention of WNV-specific neutralizing epitopes after inactivation

Reducing epitope damage during inactivation is an important parameter to consider when developing inactivated whole virus vaccines. Previously, we found that inactivation with 3% H2O2 was less damaging to specific neutralizing DI/II and DIII epitopes on WNV Env compared to inactivation by formaldehyde, BPL, heat, or UV irradiation [10]. However, even 3% H2O2 can be damaging to neutralizing epitopes as the time of inactivation increases from 4 hours to either 12 hours or 20 hours [10]. In the studies described here, the retention of neutralizing epitopes was determined following 7 hours of inactivation with 3% H2O2 (i.e., the peroxide concentration and inactivation conditions used for production of HydroVax-001 WNV [10, 12]) and compared to 20 hours of WNV inactivation using the HydroVax-II approach (Figure 2). Untreated live virus, incubated under the same buffer and temperature conditions was used as the positive control for both inactivation conditions (Figure 2A). For each neutralizing epitope that was analyzed, the HydroVax-II approach maintained a higher level of epitope retention, with an average value of 89.1 ± 5.9% (±SD) compared to 48.6 ± 14.5% (±SD) epitope retention when using the original 3% H2O2-based HydroVax conditions (Figure 2B). Similar to prior observations [10], the neutralizing epitopes identified by MAbs E121 (DI lateral ridge; DI-lr), E100 (DII dimer interface; DI-di) and E53 (DII fusion loop; DII-fl) were particularly sensitive to oxidation by 3% H2O2, retaining only 34%, 32% and 31% of the original live virus antigen signal, respectively. By comparison, virus inactivation using HydroVax-II maintained 78% (E121), 90% (E100) and 87% (E53) of the MAb binding signal observed with untreated live virus. In total, these results indicate that the advanced HydroVax-II approach provided greatly improved maintenance of neutralizing epitopes compared to the original HydroVax technology used in our previous studies [10, 12].

3.3. Immunogenicity and vaccine-mediated protection against lethal WNV infection

In addition to using an advanced oxidation approach for enhanced retention of neutralizing epitopes (Figure 2), we also developed improvements in vaccine manufacturing aimed at increasing the purity of WNV antigen used in the next-generation HydroVax-II vaccine formulation (Supplemental Figure 1). For these studies, WNV was grown in a GE WAVE bioreactor using Vero cells attached to microcarrier beads under serum-free growth conditions as previously described [10]. The virus was concentrated by TFF and either inactivated with 3% H2O2 for 7 hours and purified by ion exchange chromatography to mimic the original HydroVax approach [10] or it was further purified by multimodal core bead chromatography prior to 20 hours of inactivation using the HydroVax-II approach, followed by ion exchange chromatography. These two vaccine formulations were used to vaccinate BALB/c mice (1 μg dose administered at days 0 and 28) and serum samples were collected 28 days following the final immunization (i.e., 56 days following primary immunization) to measure neutralizing antibody titers (Figure 3). The geometric mean NT50 titer (GMT) following immunization with the 3% H2O2-inactivated HydroVax vaccine reached 320 (95% CI: 82–1248), which is comparable to the neutralizing titers observed when using the same HydroVax dose and immunization schedule in previous studies (GMT = 845 (95% CI: 97–7324, [10]). In contrast, the highly purified WNV vaccine prepared using the HydroVax-II inactivation technology induced significantly higher neutralizing antibody titers, with a GMT = 40,960 (95% CI: 14,275–117,528, P = 0.020). This represents a 130-fold increase in neutralizing antibody titers compared to the original HydroVax-001 WNV manufacturing methodology [10, 12]. As a further test of vaccine efficacy, animals were challenged with a lethal dose of wild -type WNV-NY99 (20 LD50) and monitored for morbidity (i.e., weight loss, Figure 4A, B, and C) and mortality for up to 28 days post-infection (Figure 4D). Among unvaccinated, age-matched controls, 80% of the animals lost weight (Figure 4A) and succumbed to WNV infection with a median survival time of 10 days (Figure 4D). Animals immunized with a 1 μg dose of the original HydroVax vaccine formulation showed 60% survival whereas animals that received a 1 μg dose the HydroVax-II vaccine formulation achieved 100% survival against lethal WNV infection. Together, this shows that when a limiting amount of vaccine antigen is used for immunization, the improvements associated with the advanced HydroVax-II approach provide increased immunogenicity (Figure 3) and protective efficacy (Figure 4).

Figure 3. HydroVax-II technology substantially improves WNV-specific neutralizing antibody responses.

WNV vaccine antigens were prepared using the HydroVax or HydroVax-II manufacturing and inactivation technologies and formulated with alum prior to immunizing groups of BALB/c mice (n = 5 per group) at 1 μg per dose on day 0 and day 28. Serum samples were collected at day 56 (28 days post-boost) and tested for neutralizing activity against WNV-KV. Statistical comparisons between the indicated groups were determined using one-way ANOVA.

Figure 4. HydroVax-II vaccination provides complete protection against morbidity and mortality following WNV-NY99 challenge.

Groups of BALB/c mice (n = 5/group) were vaccinated with a limited dose of 1 μg of WNV antigen prepared using the HydroVax or HydroVax-II manufacturing and inactivation approaches and compared to unvaccinated naïve controls after challenge with WNV-NY99. At 3-months post-primary vaccination (2-months post-booster vaccination), the weights of age-matched naïve mice (A) and mice immunized with the HydroVax (B) or HydroVax-II (C) vaccine were monitored daily to measure morbidity after intraperitoneal challenge with 200 PFU (20 LD50) of WNV-NY99. Animals that reached pre-determined humane euthanasia endpoints are indicated by the † symbol. (D) Comparisons of survival were made relative to naive animals using the Mantel-Cox log rank test, with significant differences relative to the naïve group indicated by an asterisk (P <0.05).

4. Discussion

Since its initial introduction in 1999, WNV has grown to become the most common mosquito-borne disease in the United States [23]. Despite nearly 20 years of circulation throughout North America, a licensed human vaccine has yet to emerge. We have previously reported on the development [8–10] of a novel H2O2-inactivated whole virus vaccine, HydroVax-001 WNV, that has proceeded to a Phase I clinical trial [12]. Here, we describe improvements to the original manufacturing approach and the use of an advanced oxidation technology (HydroVax-II) that together results in improved maintenance of neutralizing epitopes during the inactivation process and achieves a >100-fold increase in WNV-specific neutralizing antibody titers following immunization. These findings bring renewed interest to the development of a safe and effective vaccine to prevent this disabling and sometimes fatal neurotropic disease.

WNV represents an emerging/re-emerging pathogen that is endemic across the continental United States [24]. Approximately 0.5–1% of WNV cases result in neuroinvasive disease, which increases in severity with age [25]. Since 1999, greater than 45,000 WNV cases have been reported, with over 2,000 associated deaths in the US [26]. However, the true burden of disease is believed to be much higher, with estimates of nearly 3 million WNV infections resulting in approximately 780,000 illnesses [27]. In addition to the US, several European countries are now endemic with WNV [24]. In a situation analogous to the 1999 introduction of WNV to the US, Europe experienced the introduction of a pathogenic lineage 2 WNV strain in 2004, followed by westward expansion in subsequent years, impacting birds, horses, and humans [28]. Despite the prevalence of WNV across continents, no licensed human vaccine exists and early clinical results suggest that inducing robust immunity in humans may be challenging with the current vaccine approaches that have been analyzed to date.

A number of preclinical studies have explored the development of WNV vaccines, but relatively few candidates have progressed to human clinical testing [24]. Among inactivated whole virus vaccines or recombinant/subunit vaccines, achieving robust immunity in human subjects has been difficult. A recombinant WNV Env protein vaccine, WNV-80E, was tested at concentrations of up to 50 μg per dose in a three-dose series [24]. Immunogenicity at this highest dose-level was modest, with neutralizing titers of approximately 1:100 after three doses [24]. This trial was completed in 2009 (clinicaltrials.gov: NCT00707642), and appears to represent the last publicly available information on clinical testing for this candidate, leaving the current status of this program uncertain. Another clinical study examined the immunogenicity of a formaldehyde-inactivated whole virus WNV vaccine using 1.25, 2.5, 5, and 10 μg per dose in a 3-dose vaccination series on days 0, 21 and 180 [13]. At 35 days after the second dose, neutralization titers for the 10 μg dose group appeared to reach just over 50, but declined to nearly baseline levels by day 180. Administration of a third dose of vaccine led to improved neutralizing antibody responses 28 days later (day 208) but long-term antibody maintenance is unclear and this WNV vaccine program has since been terminated [13]. In earlier studies, we found that when WNV is inactivated with 0.01% formaldehyde for 20 days at 37°C (a standard concentration, time, and temperature used for formaldehyde-based inactivation [29]), there is substantial damage to particular neutralizing epitopes on the WNV Env protein [10]. Based on these studies, we speculate that the use of a formaldehyde-based inactivation approach may have led to damage of neutralizing epitopes that could not be overcome by the use of a multivalent whole-virus vaccine. The Phase I trial of HydroVax-001 WNV tested a 2-dose vaccination series using either a 1 μg or 4 μg dose formulation and the vaccine had an acceptable safety profile but only modest immunogenicity, with the 4 μg dose eliciting 50% seroconversion based on neutralizing assays performed in the presence of complement and 75% seroconversion based on WNV-specific ELISA assays [12]. Results from the analogous formaldehyde-inactivated WNV vaccine trials indicated that a higher antigen dose (e.g., 10 μg) and up to a 3-dose vaccination series may have been necessary to achieve higher, more robust WNV-specific antibody responses. In total, these results indicate that inducing robust vaccine-mediated WNV-immunity in human subjects has been challenging in the past and may require improvements in vaccine antigen content as outlined in this current paper and up to a 3-dose vaccination schedule in order to elicit optimal long-term antibody responses.

During the development of our first-generation inactivated WNV vaccine, we determined the impact of 3% H2O2 treatment on Env-specific antibody epitopes [10]. Certain amino acid side chains are more susceptible to oxidation-induced modifications than others [30]. As discussed previously [10], we speculate that the specific composition of amino acid contacts made by any particular MAb may impact how H2O2 treatment affects binding, and thus epitope retention following inactivation. For instance, structural studies of MAb E53 have demonstrated that it makes close contact with Met77 of the Env protein [31]. Considering that methionine is an amino acid that can be readily oxidized [30], this may explain why E53 is highly sensitive to 3% H2O2–based inactivation (Figure 2). We observed that DIII-mapped epitopes appeared largely resistant to H2O2-associated damage, but a number of DI and DII epitopes showed progressive damage during extended exposure to H2O2. This may have important implications in the context of clinical responses to vaccination, since prior studies indicate that human antibody responses following natural WNV infection are skewed away from DIII and towards DI and DII regions of the WNV Env protein [32, 33]. This preference for DI/DII epitopes relative to DIII in humans may explain why small animal models such as mice, known to respond robustly to DIII epitopes [33], mount strong neutralizing antibody responses following immunization with the 3% H2O2-inactivated WNV vaccine [9, 10], whereas human antibody responses were lower by comparison [12]. In this current study, we have optimized virus purification and inactivation conditions to improve functional, neutralizing antibody responses by >100-fold (Figure 3). Although antibody subclass profiles (e.g., IgG1 vs. IgG2a) were not examined, this is an important question for further study. We anticipate that an alum-formulated inactivated WNV vaccine will induce a similar Th1/Th2 profile as the commercial alum-formulated inactivated Japanese encephalitis virus vaccine, IXIARO®. Since both of these inactivated whole virus vaccines are developed to protect against encephalitic flaviviruses, it is possible that they will have a similar antibody-mediated mechanism of action.

In an effort to improve H2O2–based vaccine development, we explored the use of Fenton-type oxidation reactions. In these reactions, redox-active transition metals (such as Fe or Cu) can interact with H2O2, resulting in the production of a hydroxyl ion (HO-) and the highly reactive, but short-lived, hydroxyl radical (HO•) [33]. Fenton-type reactions have been described for the inactivation of microbial pathogens for disinfection or sterilization [34, 35], but until now have remained unexplored for vaccine development. Preliminary results with combinations of CuCl2 and H2O2 indicated that inactivation of infectious virus proceeded well with lower amounts of H2O2, but still demonstrated the potential for unwanted epitope damage (data not shown). As a further refinement to this inactivation approach, we searched for reagents known to bind Cu that might direct the oxidative reaction towards nucleic acids and away from amino acids, thereby increasing the rate of virus inactivation while shielding protein epitopes from oxidation.

Through this search, we identified methisazone (N-methylisatin β-thiosemicarbazone), a previously described antiviral molecule, as a possible candidate. Methisazone (MZ) is one of a series of antiviral drugs developed by the Wellcome Foundation in the 1950s [20]. Based on small animal efficacy studies with orthopoxviruses, MZ was developed into the commercial product, Marboran®, and tested as an oral antiviral therapy in several clinical trials for the treatment of vaccinia virus complications from smallpox vaccination, as well as for prophylaxis and treatment for smallpox [20]. For example, during a smallpox outbreak in Madras, India only 2/102 (2%) of unvaccinated MZ-treated close contacts contracted smallpox (0 deaths) whereas 28/100 (28%) of unvaccinated controls who did not receive MZ were diagnosed with smallpox and these cases resulted in 11 deaths (i.e., 39% mortality) [36]. In one study, the maximum oral dosage of MZ was 6 grams per day for 4 days (i.e., up to 24 grams, total) [37]. Later reports indicated that peak serum concentrations of MZ reached up to 0.7 μg/mL following an oral treatment course of 40 mg/kg [39], or approximately 8 grams per treatment assuming a 70 kg adult weight. Although MZ is removed from the HydroVax-II vaccine preparation by performing Cellufine sulfate chromatography, if MZ was not removed, then the hypothetical dose of MZ in a 0.5 mL vaccine dose would be approximately 0.0025 gram. Assuming that a) an adult blood volume is 4–5L, and b) all of the MZ was able to enter the bloodstream, then the final MZ serum concentration would be at least 1,000-fold lower than the serum concentrations used to treat or prevent clinical smallpox. The HydroVax-II inactivation cocktail also contains H2O2, and CuCl2, as well as formaldehyde as a stabilizing agent [14–16]. Mammalian cells naturally produce H2O2 as part of innate immune defense and peroxides are removed by enzymes including catalases and peroxidases. Copper is an essential micronutrient found in normal human serum at concentrations of 1.6–2.4 μM, a concentration that is more than 10-fold higher than the concentrations used in vitro during virus inactivation ( 0.125 μM). Although some commercial vaccines contain trace amounts of formaldehyde in the final vialed product (e.g., HAVRIX®, package insert), our vaccine approach involves removing MZ, H2O2, CuCl2, and formaldehyde prior to alum formulation and in vivo administration.

MZ, in combination with CuSO4, had been described for the use of contact inactivation of viruses [21, 40], but to our knowledge this compound has never been used in conjunction with H2O2 and had not been previously tested as a method to produce a vaccine. The exact mode of action for the MZ/Cu combination is unclear, though studies have shown that MZ will form a complex with copper, and this complex has the capacity to bind nucleic acids [22]. The ability of Cu alone to increase rates of H2O2-induced RNA and DNA modifications, including single- and double-stranded breaks, has been well-established and postulated to operate through a site-specific binding mechanism [18, 19]. However, Cu can also interact with protein in a similar site-directed manner, leading to oxidation of susceptible amino acids [41, 42]. We hypothesize that the MZ-Cu complex may preferentially bind nucleic acids, leading to the localized production of hydroxyl radicals that inactivate viruses through the oxidation of viral RNA (or DNA), while limiting free Cu from binding viral proteins and thereby decreasing the potential for structural damage to neutralizing epitopes. Indeed, the inactivation kinetics of Cu+H2O2 are more rapid in the presence of MZ (Figure 1) and in conjunction with improved retention of neutralizing epitopes (Figure 2), demonstrate that 600-fold less H2O2 (3% reduced to 0.005% H2O2) can be used to rapidly inactivate WNV while improving the maintenance of neutralizing epitopes on the surface of the virus.

Formaldehyde is one of the most common chemicals used to prepare inactivated vaccines, but when used alone under the stringent conditions of concentration/time/temperature that are typically required for clinical manufacturing, we found substantial formaldehyde-induced damage to WNV-specific neutralizing epitopes including the domain I/II epitope recognized by MAb E113 and the domain III epitope recognized by MAb E16/MGAWN1 [10]. In contrast, we found that brief exposure to low concentrations of formaldehyde can actually improve epitope retention as shown by our advanced inactivation approach that, on average, retains nearly 90% of the neutralizing antibody binding sites observed on untreated live virus (Figure 2). We chose to include a low percentage of formaldehyde in our HydroVax-II inactivation mix because studies in other model systems indicated that an optimal degree of protein cross-linking by formaldehyde could improve protein stability by increasing resistance to proteolysis [15, 16] while also stabilizing neutralizing epitopes [14]. These studies require careful optimization because over-crosslinking by formaldehyde can also lead to severe epitope damage. For example, when a genetically detoxified pertussis toxin vaccine was developed, the protein was safe but unstable and prone to degradation in vitro. Prolonged treatment with formaldehyde, analogous to the time and concentrations needed to detoxify native pertussis toxin (0.7% formaldehyde for 7 days), resulted in substantial damage to neutralizing epitopes. On the other hand, brief exposure to low concentrations of formaldehyde (0.035% for 48 hours) stabilized the genetically detoxified protein without the antigenic damage associated with prolonged formaldehyde treatment at higher concentrations [14]. Similarly, brief exposure to cross-linking agents such as formaldehyde or glutaraldehyde have also been shown to improve stability and/or immunogenicity of other recombinant subunit vaccines such as an investigational HIV trimer vaccine [43] as well as an inactivated alphavirus vaccine against Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus [44]. In this current study, we combined two independent but complementary inactivation approaches, H2O2/Cu/MZ and formaldehyde, each with different mechanisms of action (oxidation vs. protein cross-linking), that together provided rapid inactivation kinetics (Figure 1) while maintaining the structural integrity of neutralizing epitopes (Figure 2) and providing enhanced immunogenicity and protection against lethal WNV infection (Figures 3 and 4).

Endemic WNV remains a continued threat directly to humans as well as to veterinary targets including horses and several species of birds, the latter of which represent the animal reservoir that maintains zoonotic cycle of transmission of this arbovirus between mosquito vectors and their animal hosts. To better address the challenges associated with WNV vaccine development, we designed a next-generation WNV vaccine that incorporates an advanced oxidation approach for virus inactivation. This approach protects neutralizing epitopes from damage during the inactivation procedure and this technology, along with further improvements in vaccine manufacturing, provided greatly improved antiviral antibody responses and complete protection against lethal WNV infection. Through these efforts, we have identified a WNV vaccine candidate that is able to induce substantially higher neutralizing antibody responses relative to the original HydroVax-WNV vaccine formulation and this approach may be useful for not only improving vaccines against WNV but is likely to be amenable for use in the development of vaccines against a number of other human pathogens.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We thank Dr. Michael Diamond and BEI resources for supplying the WNV-specific MAbs.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [grant numbers U01 AI082196 and R44 AI079898] and the Oregon National Primate Research Center [grant number 8P51 OD011092-53].

Abbreviations:

- AEI

acetyl-ethyleneimine

- BPL

β-propiolactone

- cGMP

current good manufacturing practices

- Env

envelope protein

- FMDV

foot-and-mouth disease virus

- FIMV

formaldehyde-inactivated measles virus

- FIRSV

formaldehyde-inactivated respiratory syncytial virus

- GMT

geometric mean NT50 titer

- HA

hemagglutinin

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- IACUC

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- MZ

methisazone

- MAb

monoclonal antibody

- NT50

50% neutralizing titer

- NHP

non-human primates

- T1/2

half-life

- TFF

tangential flow filtration

- UV

ultraviolet

- WNV

West Nile virus

- WNV-KV

WNV Kunjin strain

- YFV

yellow fever virus

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: OHSU and MKS have a financial interest in Najít Technologies, Inc., a company that may have a commercial interest in the results of this research and technology. This potential individual and institutional conflict of interest has been reviewed and managed by OHSU. BKQ, DEPD and IJA are employees of Najít Technologies, Inc. AT declares no relevant conflicts of interest. No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- [1].Amanna IJ, Slifka MK. Successful Vaccines. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Food and Drug Administration. Vaccines Licensed for Use in the United States. https://www.fda.gov/biologicsbloodvaccines/vaccines/approvedproducts/. Access Date:Aug 2, 2018.

- [3].Polack FP. Atypical measles and enhanced respiratory syncytial virus disease (ERD) made simple. Pediatr Res. 2007;62:111–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hiatt CW. Kinetics of the Inactivation of Viruses. Bacteriol Rev. 1964;28:150–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Goldstein MA, Tauraso NM. Effect of formalin, beta-propiolactone, merthiolate, and ultraviolet light upon influenza virus infectivity chicken cell agglutination, hemagglutination, and antigenicity. Appl Microbiol. 1970;19:290–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Furuya Y, Regner M, Lobigs M, Koskinen A, Mullbacher A, Alsharifi M. Effect of inactivation method on the cross-protective immunity induced by whole ‘killed’ influenza A viruses and commercial vaccine preparations. J Gen Virol. 2010;91:1450–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jonges M, Liu WM, van der Vries E, Jacobi R, Pronk I, Boog C, et al. Influenza virus inactivation for studies of antigenicity and phenotypic neuraminidase inhibitor resistance profiling. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:928–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Amanna IJ, Raue HP, Slifka MK. Development of a new hydrogen peroxide-based vaccine platform. Nat Med. 2012;18:974–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Pinto AK, Richner JM, Poore EA, Patil PP, Amanna IJ, Slifka MK, et al. A hydrogen peroxide-inactivated virus vaccine elicits humoral and cellular immunity and protects against lethal West Nile virus infection in aged mice. J Virol. 2013;87:1926–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Poore EA, Slifka DK, Raue HP, Thomas A, Hammarlund E, Quintel BK, et al. Pre-clinical development of a hydrogen peroxide-inactivated West Nile virus vaccine. Vaccine. 2017;35:283–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Walker JM, Raue HP, Slifka MK. Characterization of CD8+ T cell function and immunodominance generated with an H2O2-inactivated whole-virus vaccine. J Virol. 2012;86:13735–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Woods CW, Sanchez AM, Swamy GK, McClain MT, Harrington L, Freeman D, et al. An Observer Blinded, Randomized, Placebo-controlled, Phase I Dose Escalation Trial to Evaluate the Safety and Immunogenicity of an Inactivated West Nile Virus Vaccine, HydroVax-001, in Healthy Adults. Vaccine. 2018;Manuscript Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Barrett PN, Terpening SJ, Snow D, Cobb RR, Kistner O. Vero cell technology for rapid development of inactivated whole virus vaccines for emerging viral diseases. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2017;16:883–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Rappuoli R Toxin inactivation and antigen stabilization: two different uses of formaldehyde. Vaccine. 1994;12:579–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Delamarre L, Couture R, Mellman I, Trombetta ES. Enhancing immunogenicity by limiting susceptibility to lysosomal proteolysis. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2049–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Porro M, Saletti M, Nencioni L, Tagliaferri L, Marsili I. Immunogenic correlation between cross-reacting material (CRM197) produced by a mutant of Corynebacterium diphtheriae and diphtheria toxoid. J Infect Dis. 1980;142:716–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Barbusiński K Fenton Reaction - Controversy concerning the chemistry. Ecological Chemistry and Engineering. 2009;16: 347–58. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Massie HR, Samis HV, Baird MB. The kinetics of degradation of DNA and RNA by H2O2 Biochim Biophys Acta. 1972;272:539–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Rodriguez H, Drouin R, Holmquist GP, O’Connor TR, Boiteux S, Laval J, et al. Mapping of copper/hydrogen peroxide-induced DNA damage at nucleotide resolution in human genomic DNA by ligation-mediated polymerase chain reaction. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17633–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bauer DJ. The Specific Treatment of Virus Diseases. Lancaster: MTP Press Limited; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Fox MP, Bopp LH, Pfau CJ. Contact inactivation of RNA and DNA viruses by N-methyl isatin beta-thiosemicarbazone and CuSO4. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1977;284:533–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Mikelens PE, Woodson BA, Levinson WE. Association of nucleic acids with complexes of N-methyl isatin-beta-thiosemicarbazone and copper. Biochem Pharmacol. 1976;25:821–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Burakoff A, Lehman J, Fischer M, Staples JE, Lindsey NP. West Nile Virus and Other Nationally Notifiable Arboviral Diseases - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:13–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Amanna IJ, Slifka MK. Current trends in West Nile virus vaccine development. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2014;13:589–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lindsey NP, Staples JE, Delorey MJ, Fischer M. Lack of evidence of increased West Nile virus disease severity in the United States in 2012. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;90:163–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. West Nile virus. https://www.cdc.gov/westnile/. Access Date:Aug 6, 2018.

- [27].Petersen LR, Carson PJ, Biggerstaff BJ, Custer B, Borchardt SM, Busch MP. Estimated cumulative incidence of West Nile virus infection in US adults, 1999–2010. Epidemiol Infect. 2013;141:591–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bakonyi T, Ferenczi E, Erdelyi K, Kutasi O, Csorgo T, Seidel B, et al. Explosive spread of a neuroinvasive lineage 2 West Nile virus in Central Europe, 2008/2009. Vet Microbiol. 2013;165:61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Armstrong ME, Giesa PA, Davide JP, Redner F, Waterbury JA, Rhoad AE, et al. Development of the formalin-inactivated hepatitis A vaccine, VAQTA from the live attenuated virus strain CR326 F. J Hepatol. 1993;18 Suppl 2:S20–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Stadtman ER, Levine RL. Free radical-mediated oxidation of free amino acids and amino acid residues in proteins. Amino Acids. 2003;25:207–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Cherrier MV, Kaufmann B, Nybakken GE, Lok SM, Warren JT, Chen BR, et al. Structural basis for the preferential recognition of immature flaviviruses by a fusion-loop antibody. EMBO J. 2009;28:3269–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Chabierski S, Makert GR, Kerzhner A, Barzon L, Fiebig P, Liebert UG, et al. Antibody responses in humans infected with newly emerging strains of West Nile Virus in Europe. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Oliphant T, Nybakken GE, Austin SK, Xu Q, Bramson J, Loeb M, et al. Induction of epitope-specific neutralizing antibodies against West Nile virus. J Virol. 2007;81:11828–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Sagripanti JL, Routson LB, Lytle CD. Virus inactivation by copper or iron ions alone and in the presence of peroxide. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:4374–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Nieto-Juarez JI, Pierzchla K, Sienkiewicz A, Kohn T. Inactivation of MS2 coliphage in Fenton and Fenton-like systems: role of transition metals, hydrogen peroxide and sunlight. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44:3351–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Bauer DJ, Stvincent L, Kempe CH, Downie AW. Prophylactic Treatment of Small Pox Contacts with N-Methylisatin Beta-Thiosemicarbazone (Compound 33t57, Marboran). Lancet. 1963;2:494–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Bauer DJ. Clinical experience with the antiviral drug marboran (1-methylisatin 3-thiosemicarbazone). Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1965;130:110–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].McLean DM. Vaccinia complications and methisazone therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Gomez CP, Sandeman TF. Measuring Methisazone Serum-Levels. The Lancet. 1966;288:233. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Logan JC, Fox MP, Morgan JH, Makohon AM, Pfau CJ. Arenavirus inactivation on contact with N-substituted isatin beta-thiosemicarbazones and certain cations. J Gen Virol. 1975;28:271–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Ramirez DC, Mejiba SE, Mason RP. Copper-catalyzed protein oxidation and its modulation by carbon dioxide: enhancement of protein radicals in cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:27402–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kocha T, Yamaguchi M, Ohtaki H, Fukuda T, Aoyagi T. Hydrogen peroxide-mediated degradation of protein: different oxidation modes of copper- and iron-dependent hydroxyl radicals on the degradation of albumin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1337:319–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Feng Y, Tran K, Bale S, Kumar S, Guenaga J, Wilson R, et al. Thermostability of Well-Ordered HIV Spikes Correlates with the Elicitation of Autologous Tier 2 Neutralizing Antibodies. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Greenway TE, Eldridge JH, Ludwig G, Staas JK, Smith JF, Gilley RM, et al. Enhancement of protective immune responses to Venezuelan equine encephalitis (VEE) virus with microencapsulated vaccine. Vaccine. 1995;13:1411–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Beigel JH, Nordstrom JL, Pillemer SR, Roncal C, Goldwater DR, Li H, et al. Safety and pharmacokinetics of single intravenous dose of MGAWN1, a novel monoclonal antibody to West Nile virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:2431–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.