Abstract

Background.

Young adults are at high risk for using flavored tobacco, including menthol, and underrepresented populations, such as Latino and African American young adults are at particular risk.

Objectives.

The purpose of this study is to identify sociodemographic correlates of menthol use among young adult smokers and examine the potential role of experienced discrimination in explaining any associations.

Methods.

We conducted a probabilistic multimode household survey of young adults (aged 18–26) residing in Alameda and San Francisco Counties in California in 2014 (n=1,350). We used logistic regression to evaluate associations between menthol cigarette use and experienced discrimination among young adult smokers as well as with respect to sociodemographic, attitudinal and behavioral predictors. Interactions between experienced discrimination and race/ethnicity, sex and LGB identity were also modeled.

Results.

Latino and non-Hispanic Black young adult smokers were more likely to report current menthol use than non-Hispanic Whites, while those with college education were less likely to do so. Experienced discrimination mediated the relationship between race and menthol use for Asian/Pacific Islander and Multiracial young adult smokers with odds of use increasing by 32% and 42% respectively for each additional unit on the experienced discrimination scale.

Conclusions/Importance.

Latino and African American young adult smokers have disproportionately high menthol use rates, however discrimination only predicted higher use for Asian/Pacific Islander and Multiracial young adult smokers. Limits on the sale of menthol cigarettes may benefit all nonwhite race/ethnic groups as well as those with less education.

Keywords: tobacco control, flavored tobacco, health disparities, smoking

1. INTRODUCTION

In 2009 as part of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration banned the use of “characterizing flavors” such as candy or chocolate in cigarettes, noting that flavors entice youth to start smoking.1 However, tobacco industry pressure ensured that menthol, a mint flavoring that triggers cooling and soothing sensations when smoked, was exempt from this ban.2 To address this omission, fourteen towns and counties in California, including San Francisco and Oakland, have adopted their own bans of flavored tobacco product sales since 2014, and ten of these include menthol.3 This legislation has the potential to reduce disparities in smoking prevalence by reducing smoking rates in groups with higher menthol cigarette use, including youth and young adult smokers and specifically among female and nonwhite smokers.4

Historically, the tobacco industry has targeted these populations with tobacco promotions generally and menthol promotions specifically.5,6 The most well known example of this targeting has taken place with African Americans,7 resulting in disproportionately high rates of menthol use; 70% of African American adult smokers have been shown to use menthol cigarettes compared to approximately 26% of all U.S. adult smokers.4,8 The tobacco industry cultivated menthol use among African Americans during the Civil Rights era, advertising menthol brand cigarettes in urban, predominantly African American neighborhoods, providing money to African American civil rights organizations,9 and cultivating an ethos among African American activist youth to promote menthol brands such as “Kool” in alignment with cultural values of defiance and modernity.8 The strategy has been so successful that even by 6th grade, African American youth were three times more likely to recognize menthol brands than their peers.14 Such brand recognition helps initate new users; young people who recognized the Newport brand were more likely to initiate smoking within the following 12 months.14

Women were also an early target population for menthol advertising,10 and more recent studies have demonstrated greater investment in menthol advertising targeted to Latinos.11 Less is known about the extent of targeted menthol marketing aimed at LGBT youth; however, the tobacco industry has targeted LGBT populations more generally by advertising in LGBT media and funding LGBT and AIDS organizations.12,13 LGBT individuals have been shown to smoke menthol cigarettes at higher rates than their heterosexual counterparts.6

Young adulthood is a critical stage in smoking initiation and continuation and nearly 99% of smokers begin smoking by the age of 26.14 The tobacco industry capitalizes on the uncertainty and transitions in young adulthood and uses age-specific promotions like music, sporting, bar and party events to encourage young adults to associate smoking with normal adult life and to promote flavored tobacco products.15 Young people often begin by using flavored products such as menthol cigarettes, which the tobacco industry developed largely as a means to recruit youth smokers.16–18 Young adults may also perceive menthol cigarettes to be safer19 than non-menthol cigarettes, even though evidence suggests they may be harder to quit.20,21 Adolescents and young adults use menthol at higher rates than other age groups; according to the 2004–2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, among smokers, 57% of youth aged 12–17 and 45% of young adults aged 18–25 smoked menthol cigarettes compared to 31–35% of older groups.4 Within specific demographic groups, menthol use rates are even higher.

In light of tobacco industry targeting of minority groups with menthol advertising and promotion, there is a distinct possibility that groups at higher risk for tobacco and menthol cigarette use are also more likely to experience discrimination in daily interactions with businesses, social institutions and networks. Previous studies have shown positive relationships between perceived discrimination and tobacco or other substance use, as well as discrimination and health disparities in general,22 including for young boys;17 African American adolescents and adults,18,23 women,19 and men;20 Asians and Pacific Islanders,21 Latina adolescents24 and all U.S. adults regardless of race.22

A variety of physiological/pharmacological, psychological, and social/environmental factors have been found to influence menthol cigarette use among Black and Latino individuals, and discrimination has been noted as a potential culturally specific cue to initiate and maintain menthol smoking. Menthol cigarette smoking may act as a means of coping with stressors like discrimination through affiliation with other smokers or as part of a traditional cultural orientation toward health practices that views menthol as medicinal.25 However, little research has examined menthol cigarette smoking and experienced discrimination directly. Furthermore, most population-based research on flavored tobacco products has focused on adolescents rather than young adults, which neglects the substantial proportion of young people who initiate smoking after adolesence;26,27 and much of the existing menthol research focuses on specific population subgroups that have already been identified as high risk.19,21,28,29

In this study we leverage data from the first probabilistic multimode household survey of young adults ages 18 to 26 in the San Francisco Bay Area (2014) to achieve three objectives: (1) evaluate whether there are sociodemographic differences in menthol use among young adult smokers; (2) identify whether experienced discrimination predicts menthol use; and (3) determine whether any independent associations found between menthol use and race/ethnicity, sex and sexual orientation are partially mediated by experienced discrimination.

2. METHODS

2.1. Sample

This study utilized data from the 2014 San Francisco Bay Area Young Adult Health Survey (BAYAHS), a probabilistic multi-mode household survey of 18–26-year-old young adults, stratified by race/ethnicity. The study area included Alameda and San Francisco Counties in California. We identified potential respondent households using address lists obtained from Marketing Systems Group wherein there was an approximately 40% chance that an eligible young adult resided at a selected address (n=15,000 addresses). The survey was conducted in three phases and employed four modes (mail/web, telephone, face-to-face). Our procedure has been published in more detail elsewhere.30,31 In addition to the address lists, for the face-to-face interviews we also used 2009–2013 American Community Survey and 2010 decennial census data in a multistage sampling design to identify Census Block Groups and subsequently Census Blocks in which at least 15% of residents were in the eligible age range (n=1,636 housing units) to randomly select 61 blocks. We oversampled blocks with higher concentrations of Black and Latino young adults as these populations are particularly hard to reach. We canvassed each of the 61 selected blocks, to enumerate all housing units, and randomly selected households to visit from these block-level address lists. If more than one eligible young adult resided in the selected household, we randomly selected a young adult to complete the questionnaire.

The final sample consisted of 1,363 young adult participants with race, sex and age distributions closely reflecting those of the young adult population overall in the two counties surveyed. Individual sample and post-stratification adjustment weights were constructed after data collection.

2.2. Measures

Menthol use.

We asked respondents two questions to ascertain menthol cigarette use: first, “during the past 30 days, on how many days (0–30) did you smoke at least one cigarette?” and second, “when you smoke cigarettes, what is the TYPE you most often smoke?” with the following response categories: “non-menthol”, “menthol,” “clove or flavored” or “no usual type.” Respondents who had smoked at least one cigarette in the past 30 days and indicated that they most often smoked “menthol” cigarettes were classified as menthol users.

2.21. Explanatory Factors

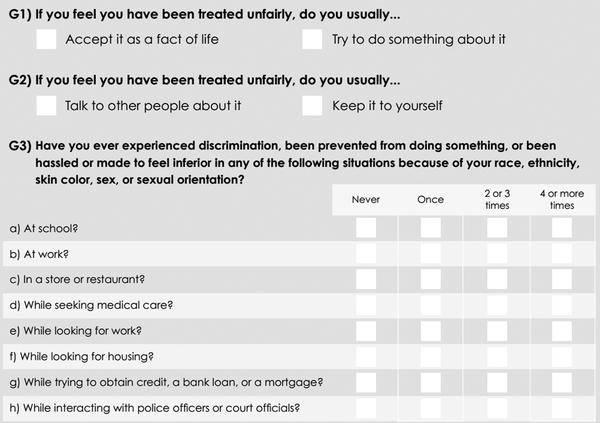

Experienced Discrimination (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Modified Experiences of Discrimination Scale, 2014 BAYAHS Instrument.

The main explanatory measure was based on the Experiences of Discrimination Scale,32 which has previously demonstrated a relationship between discrimination and smoking for Black and Latino populations. Our scale, which we modified to include sexual orientation, was scored in the same manner as the original scale; specifically, the first two items were scored together on a three-point scale, set equal to ‘0’ for a passive response, i.e. respondent answered “accept it as a fact of life” to G1 and “keep it to yourself” to G2; “1” for a moderate response, i.e. respondent answered either “accept it as a fact of life” and “talk to other people about it,” or “try to do something about it” and “keep it to yourself;” and ‘2’ for an active response, i.e. respondent answers “try to do something about it” and “talk to other people about it.” That score was then added to the scoring for each item in G3 where “never” was set to ‘0,’ “once” was set to ‘1,’ “2 or 3 times” was set to ‘2.5’ and “4 or more times” was set to ‘5.’ The scores for the final composite measure range from 0 to 42, where higher scores indicate more reported experienced discrimination.

Sociodemographic Characteristics.

We assessed respondent age, sex, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and educational attainment. Age was calculated using respondent birthdate and year; self-reported race/ethnicity is categorical, indicating whether a respondent was Hispanic or non-Hispanic White, Black, Asian/Pacific Islander or Other Race. Respondents could select multiple race categories, and those who selected more than one category and were not Hispanic, or who identified exclusively as American Indian/Alaska Native were classified as “non-Hispanic Other Race.” The remaining measures are dichotomous. Sex was coded as ‘1’ if the respondent was male, 0 otherwise; LGB was coded as ‘1’ if the respondent identified as homosexual or bisexual (no respondents identified as transgender); and a ‘1’ was assigned to those respondents who were currently enrolled in college or had attained at least a Bachelor’s degree.

2.3. Covariates

Tobacco Attitudes, Health Behavior & Status.

We included one attitudinal variable, two behavioral variables, and a measure of general health. The attitudinal response was measured continuously, on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all” (1) to “extremely” (7). Respondents indicated “to what extent do you agree with the following statement…;” as in prior studies,33,34 responses to three items (“I want to be involved in efforts to get rid of cigarette smoking,” “I would like to see cigarette companies go out of business,” and “taking a stand against smoking is important to me”) were averaged to indicate anti-tobacco industry attitudes. Frequency of bar attendance was measured with the item “how often do you go to bars or clubs” and was measured on a four-point scale from “never” (1) to “frequently” (4). Nicotine dependence was measured dichotomously and set equal to ‘1’ if respondents indicated that they smoke their first cigarette “less than 30 minutes after I wake up.” Very good or excellent self-rated health was also measured dichotomously and equaled ‘1’ if the respondent reported being in very good or excellent, as opposed to good, fair or poor general health.

2.4. Analysis

We used Stata v14 to perform an iterative logistic regression using the “svyset” command to adjust for the complex sampling design. To account for missing data, we used Stata’s multiple imputation for chained equations capabilities and tested the models with and without the imputed results to ensure no significant bias was introduced. The final sample included 1350 of 1363 total observations; 13 observations were dropped due to incomplete questionnaires that were missing data for more than 50 percent of questionnaire items, including race/ethnicity and tobacco use data. We used the “subpop” command in Stata v14 to measure menthol use among those young adults who had smoked cigarettes at least one day in the previous 30, leaving non-menthol cigarette smokers as the reference group. The subpop command utilizes the entire sample to calculate standard errors.

We generated interaction terms between the experiences of discrimination scale and sex, each of the race/ethnicity categories and LGB identification to evaluate whether the relationships between experienced discrimination and sex and racial or sexual minority status explained any differences in menthol use. First, we modeled menthol use with sociodemographic variables to assess independent effects of these characteristics. We then added tobacco attitudes in Model 2 before adding health behavior and status in Model 3. The experiences of discrimination score was entered in the fourth model to determine whether discrimination explained differences in menthol use by race/ethnicity or LGBT identification. Finally, the interaction terms were added (Model 5) to evaluate whether associations between menthol use and individual characteristics were mediated by experienced discrimination.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Sample Characteristics

In our sample, approximately 15% of young adults were current smokers, and 40% of current smokers used menthol cigarettes. Among current smokers, Latino and non-Hispanic Black young adults were significantly more likely than average to smoke menthol cigarettes while non-Hispanic Whites were significantly less likely to do so (Figure 2). Women and LGB smokers also had higher prevalence rates of menthol use though not statistically higher than average.

Figure 2.

Menthol Cigarette Use among Young Adult Smokers (n=190), 2014 BAYAHS

*Significantly higher than mean; †significantly lower than mean All race categories are non-Hispanic and mutually exclusive.

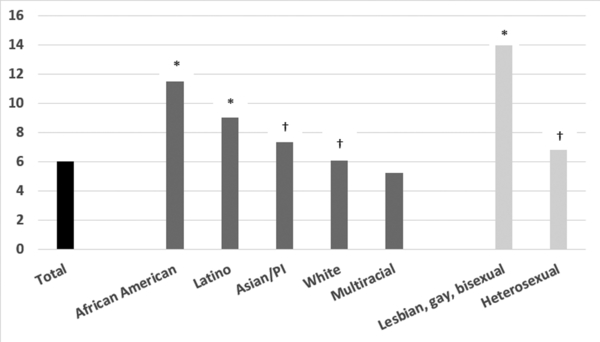

Latino and African American young adults also reported statistically higher scores on the experiences of discrimination scale than their non-Hispanic White and Asian/Pacific Islander counterparts, and LGB young adults had higher reports of experienced discrimination than heterosexual young adults (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Mean Scores on Experiences of Discrimination Scale among Young Adult Smokers by Race/Ethnicity (n=190), 2014 BAYAHS

*Significantly higher than mean; †significantly lower than mean All race categories are non-Hispanic and mutually exclusive

Table 1 reports weighted sample characteristics for nonsmokers compared to smokers who do not use menthol and smokers who do. Average age across the three groups was approximately 22 years. Among menthol cigarette smokers compared to non-menthol smokers, a lower proportion was male (53.8% vs. 63.9%), while greater proportions were Latino (43.8% vs. 20.3%) or non-Hispanic Black (23.1% vs. 4.9%) and lesbian, gay or bisexual (17.9% vs. 9.2%). A substantially smaller proportion of menthol smokers were currently enrolled in or had graduated from college (51.3%) compared to both non-menthol smokers (78.6%) and nonsmokers (85.5%). Menthol smokers were also the most likely to frequent bars, and had stronger anti-tobacco industry attitudes than non-menthol smokers (3.5/7 versus 2.9). They also exhibited higher nicotine dependence (18.5% compared to 12.1% of smokers who did not use menthol) and were less likely to report being in very good or excellent health (19.3% versus 54.3%). Finally, menthol cigarette smokers had higher scores on the experiences of discrimination scale (8.6/42) than both non-menthol smokers (7.4) and nonsmokers (5.8).

Table 1.

Weighted Sample Characteristics, 2014 San Francisco Bay Area Young Adult Health Survey (n=1350)

| Characteristic | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (18–26) | (2.5) | (2.5) | (2.6) |

| Male | |||

| Non-Hispanic White (referent) | |||

| Latino | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | |||

| Non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander | |||

| Non-Hispanic Multiracial | |||

| Lesbian, gay or bisexual | |||

| Graduated from or currently enrolled in college | |||

| Anti-tobacco industry (1–7) | (1.8) | (1.6) | (1.9) |

| Health Behavior/Status | |||

| Bar attendance frequency (1–4) | (0.9) | (1.0) | (1.0) |

| Nicotine dependent | |||

| Very good/excellent self-rated health | |||

| Scale (0–42) | (6.0) | (6.9) | (7.5) |

Logistic Regression Results

Table 2 shows logistic regression results for menthol use, adjusted for experienced discrimination, sociodemographic characteristics, and covariates. In the fully adjusted model without interaction terms (Model 4) being Latino, non-Hispanic Black or non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander compared to non-Hispanic White was positively associated with a higher rate of menthol use among smokers. Current enrollment in college or having graduated from college was negatively associated with menthol use. Contrary to expectation, higher ratings on the experiences of discrimination scale were not associated with menthol use among smokers.

Table 2.

Logistic regression models estimating associations between menthol smoking and sociodemographic, behavioral and attitudinal variables and experienced discrimination: 2014 San Francisco Bay Area Young Adult Health Survey

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI |

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | ||||||||

| Age | 0.96 | [ 0.83 , 1.12 ] | 0.77 | [ 0.65 , 0.92 ] | 0.77 | [ 0.66 , 0.91 ] | 0.80 | [ 0.68 , 0.94 ] |

| Male | 1.42 | [ 0.68 , 2.97 ] | 1.20 | [ 0.47 , 3.08 ] | 1.21 | [ 0.48 , 3.05 ] | 2.40 | [ 0.76 , 7.63 ] |

| NH White (referent) | ||||||||

| Latino | 4.35 | [ 1.49 , 12.72 ] | 5.21 | [ 1.37 , 19.74 ] | 5.07 | [ 1.32 , 19.41 ] | 4.78 | [ 0.96 , 23.80 ] |

| NH Black | 6.61 | [ 1.83 , 23.83 ] | 7.74 | [ 1.64 , 36.46 ] | 7.30 | [ 1.46 , 36.42 ] | 10.48 | [ 1.31 , 83.83 ] |

| NH API | 1.89 | [ 0.62 , 5.70 ] | 3.10 | [ 0.77 , 12.54 ] | 3.00 | [ 0.74 , 12.12 ] | 1.37 | [ 0.26 , 7.38 ] |

| NH Other | 0.34 | [ 0.08 , 1.48 ] | 0.59 | [ 0.10 , 3.62 ] | 0.57 | [ 0.09 , 3.52 ] | 0.45 | [ 0.06 , 3.57 ] |

| LGBT | 2.09 | [ 0.78 , 5.63 ] | 1.72 | [ 0.49 , 5.97 ] | 1.68 | [ 0.52 , 5.45 ] | 0.14 | [ 0.01 , 1.43 ] |

| Graduated from or currently enrolled in college | 0.22 | [ 0.10 , 0.48 ] | 0.23 | [ 0.10 , 0.51 ] | 0.23 | [ 0.10 , 0.52 ] | 0.23 | [ 0.10 , 0.54 ] |

| Tobacco Attitudes & Health Status | ||||||||

| Smoking reduces stress | 1.36 | [ 1.08 , 1.71 ] | 1.36 | [ 1.09 , 1.71 ] | 1.39 | [ 1.12 , 1.72 ] | ||

| Anti-industry | 0.98 | [ 0.75 , 1.27 ] | 0.98 | [ 0.75 , 1.26 ] | 0.97 | [ 0.77 , 1.22 ] | ||

| Bar attendance frequency | 2.78 | [ 1.76 , 4.38 ] | 2.72 | [ 1.71 , 4.31 ] | 3.11 | [ 1.96 , 4.94 ] | ||

| Nicotine dependent | 8.53 | [ 2.27 , 32.03 ] | 8.37 | [ 2.19 , 32.05 ] | 7.46 | [ 2.09 , 26.59 ] | ||

| Very good/excellent self-rated health | 0.18 | [ 0.08 , 0.43 ] | 0.18 | [ 0.08 , 0.44 ] | 0.18 | [ 0.07 , 0.43 ] | ||

| Experiences of Discrimination | ||||||||

| Scale (0–42) | 1.01 | [ 0.96 , 1.07 ] | 0.96 | [ 0.77 , 1.19 ] | ||||

| Interaction Terms | ||||||||

| EOD Scale*Male | 0.94 | [ 0.84 1.05 ] | ||||||

| EOD Scale*Latino | 1.03 | [ 0.83 , 1.27 ] | ||||||

| EOD Scale*NH Black | 1.03 | [ 0.83 , 1.27 ] | ||||||

| EOD Scale*NH Asian/PI | 1.14 | [ 0.91 , 1.44 ] | ||||||

| EOD Scale*NH Other | 1.08 | [ 0.86 , 1.36 ] | ||||||

| EOD Scale*LGBT | 1.28 | [ 1.06 , 1.53 ] | ||||||

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval

We entered the interaction terms in Model 5 to determine whether there are specific attributes of race/ethnicity or sexual minority status in combination with experienced discrimination that may drive independent associations between demographic characteristics and the likelihood of smoking menthol cigarettes. We found significant interaction between experienced discrimination and race/ethnicity for non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander young adult smokers as well as Multiracial young adult smokers; specifically, each additional unit on the experienced discrimination scale corresponds to 32% higher odds of menthol use among Asian/Pacific Islander young adult smokers, and 42% higher odds among Multiracial young adult smokers.

4. DISCUSSION

Consistent with previous studies of adult and adolescent populations, we found that Latino and non-Hispanic Black young adult smokers were more likely to smoke menthol cigarettes than non-Hispanic White young adult smokers. This disproportionate menthol use was independent of experienced discrimination. We found evidence that experienced discrimination mediates associations between demographic characteristics and menthol use for Asian/Pacific Islander and Multiracial young adult smokers; not only are non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander young adult smokers more likely to smoke menthol cigarettes, but their odds of use increase with additional experiences of discrimination. The latter is also true for Multiracial young adult smokers. We further found that little or no college education was associated with greater odds of menthol use. There was no difference in menthol use by sex or sexual orientation. Flavored tobacco product policies are therefore likely to impact menthol use habits among all race/ethnic groups compared to non-Hispanic Whites and among young adults with less education.

Our findings suggest that everyday experiences of discrimination partially explain observed higher odds of menthol use among Asian/Pacific Islander and Multiracial young adult smokers but not among the two groups most heavily targeted in menthol advertising and with the highest prevalence use rates, Latino and Black young adults. This finding is consistent with a prior study of Black adult smokers that did not find an association between perceived discrimination and menthol use.35 This null finding suggests that other more structural inequities or differences might help explain higher menthol use among Latino and Black young adult smokers, potentially including greater exposure to targeted marketing. For example, California high schools with greater proportions of Black students were surrounded by significantly more menthol advertising and significantly lower prices for Newport, the leading menthol cigarette brand.36 It also indicates that there might be a normalization of menthol use in some groups (e.g., African Americans) that drives higher rates of menthol use, consistent with previous studies finding menthol use was associated with greater numbers of menthol smokers in one’s social network.35

For groups where menthol use might not be part of a cultural norm (e.g., Asian and Multiracial young adults), the greater use of menthol cigarettes among those reporting experienced discrimination warrants further exploration. Greater menthol use might be related to enhanced perceptions of stress relief with menthol cigarettes due to menthol’s physiologic properties25 or association with medicinal qualities, connections between menthol cigarettes and other substance use,38 or greater menthol cigarette promotion or availability to those experiencing discrimination. With respect to health behavior and status, we also find that young adult smokers who attend bars/clubs more frequently are significantly more likely to smoke menthol cigarettes. This suggests that policies that reduce the availability of menthol cigarettes might particularly affect these high-risk young adults.

This study has some limitations. First, these data are restricted to 18–26-year-old adults in the San Francisco Bay Area and the results may not generalize to all populations. Secondly, our tobacco use data are self-reported and we cannot biochemically verify smoking or nicotine addiction among our participants. However, biochemical validation is not typically recommended for large scale population-based studies with limited participant contact such as this.39 Third, this data set measured only experienced discrimination and did not include questions addressing menthol-specific perceptions (e.g., medicinal qualities) that have been associated with menthol use.

4.1. Public Health Implications

In keeping with prior research, we found significant racial/ethnic disparities in menthol cigarette smoking among young adults in the Bay Area with Latinos and non-Hispanic Blacks demonstrating the highest odds of use and non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander and Multiracial young adults showing greater odds of use with greater experienced discrimination. Less educated young adults and those who attended bars more frequently also had higher odds of menthol use. Thus, local policies limiting the sales of menthol cigarettes have the potential to particularly benefit racial/ethnic minority and high-risk young adults by potentially reducing smoking overall and discouraging co-use of harmful behaviors such as alcohol use and smoking.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the National Cancer Institute (U01-154240), the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (P60 MD006902) and the National Cancer Institute (T32CA113710-11).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Center for Tobacco Products. General Questions and Answers on the Ban of Cigarettes that Contain Certain Characterizing Flavors. Washington D.C.: Food and Drug Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services;2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitka M FDA exercises new authority to regulate tobacco products, but some limits remain. JAMA. 2009;302(19):2078–2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tobacco Control Section. California Flavored Tobacco and Menthol Cigarette Policy Matrix. Sacramento, CA: California Department of Health Services;2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO Study Group on Tobacco Product Regulation. Banning Menthol in Tobacco Products. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee YO, Glantz SA. Menthol: putting the pieces together. Tobacco Control. 2011;20(Suppl 2):ii1–ii7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fallin A, Goodin AJ, King BA. Menthol cigarette smoking among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adults. Am. J. Prev. Med 2015;48:93–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balbach ED, Gasior RJ, Barbeau EM. R.J. Reynolds’ Targeting of African Americans: 1988–2000. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(5):822–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gardiner PS. The African Americanization of menthol cigarette use in the United States. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6 Suppl 1:S55–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yerger VB, Malone RE. African American leadership groups: Smoking with the enemy. Tobacco Control. 2002;11:336–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson SJ. Marketing of menthol cigarettes and consumer perceptions: a review of tobacco industry documents. Tobacco Control. 2011;20(Suppl 2):ii20–ii28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landrine H, Klonoff EA, Fernandez S, et al. Cigarette advertising in Black, Latino, and White magazines, 1998–2002: an exploratory investigation. Ethnicity & disease. 2005;15(1):63–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith EA, Malone RE. The outing of Philip Morris: Advertising tobacco to gay men. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:988–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith J, Thompson S, Lee K. “Public Enemy No. 1”: Tobacco industry funding for the AIDS response. SAHARA-J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS. 2016;13:41–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Office of the Surgeon General. Preventing Tobacco Use among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services;2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ling PM, Glantz SA. Why and How the Tobacco Industry Sells Cigarettes to Young Adults: Evidence From Industry Documents. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(6):908–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carpenter CM, Wayne GF, Pauly JL, Koh HK, Connolly GN. New Cigarette Brands With Flavors That Appeal To Youth: Tobacco Marketing Strategies. Health Affairs. 2005;24(6):1601–1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wayne GF, Connolly GN. How cigarette design can affect youth initiation into smoking: Camel cigarettes 1983–93. Tobacco Control. 2002;11(suppl 1):i32–i39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ambrose BK, Day HR, Rostron B, et al. Flavored tobacco product use among us youth aged 12–17 years, 2013–2014. JAMA. 2015;314(17):1871–1873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Unger JB, Allen B, Leonard E, Wenten M, Cruz TB. Menthol and non-menthol cigarette use among black smokers in Southern California. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2010;12:398–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pletcher MJ, Hulley BJ, Houston T, Kiefe CI, Benowitz N, Sidney S. Menthol cigarettes, smoking cessation, atherosclerosis, and pulmonary function. 2006;166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trinidad DR, Pérez-Stable EJ, Messer K, White MM, Pierce JP. Menthol Cigarettes and Smoking Cessation among Racial/ethnic Groups in the United States. Addiction. 2010;105:84–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Assari S Health Disparities due to Diminished Return among Black Americans: Public Policy Solutions. Social Issues and Policy Review. 2018;12(1):112–145. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibbons FX, Yeh H-C, Gerrard M, et al. Early experience with racial discrimination and conduct disorder as predictors of subsequent drug use: A critical period hypothesis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88:S27–S37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Soto D, Baezconde-Garbanati L. Acculturation, Gender, Depression, and Cigarette Smoking Among U.S. Hispanic Youth: The Mediating Role of Perceived Discrimination. J Youth Adolescence. 2011;40(11):1519–1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castro FG. Physiological, psychological, social, and cultural influences on the use of menthol cigarettes among Blacks and Hispanics. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6(Suppl 1):S29–S41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernander A, Rayens MK, Zhang M, Adkins S. Are age of smoking initiation and purchasing patterns associated with menthol smoking? Addiction. 2010;105:39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holmes LM, Marcelli EA, Ling PM. San Francisco Bay Area Young Adult Health Survey (BAYAHS). San Francisco, CA: Center for Tobacco Control Research & Education, University of California San Francisco;2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guthrie BJ, Young AM, Williams DR, Boyd CJ, Kintner EK. African American Girls’ Smoking Habits and Day-to-Day Experiences With Racial Discrimination. Nursing Research. 2002;51:183–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parker LJ, Kinlock BL, Chisolm D, Furr-Holden D, Thorpe RJ Jr. Association Between Any Major Discrimination and Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adult African American Men. Substance Use & Misuse. 2016;51:1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holmes LM, Ling PM. Workplace secondhand smoke exposure: a lingering hazard for young adults in California. Tob. Control. 2016;Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holmes LM, Popova L, Ling PM. State of transition: Marijuana use among young adults in the San Francisco Bay Area. Preventive Medicine. 2016;90:11–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, Barbeau EM. Experiences of Discrimination: Validity and Reliability of a Self-report Measure for Population Health Research on Racism and Health. Soc. Sci. Med 2005;61:1576–1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ling PM, Neilands TB, Glantz SA. The Effect of Support for Action Against the Tobacco Industry on Smoking Among Young Adults. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(8):1449–1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ling PM, Neilands TB, Glantz SA. Young Adult Smoking Behavior: A National Survey. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;36(5):389–394.e382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Unger JB, Allen B, Leonard E, Wenten M, Cruz TB. Menthol and non–menthol cigarette use among Black smokers in Southern California. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;12(4):398–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henriksen L, Schleicher NC, Dauphinee AL, Fortmann SP. Targeted Advertising, Promotion, and Price For Menthol Cigarettes in California High School Neighborhoods. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2012;14(1):116–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kendzor DE, Businelle MS, Reitzel LR, et al. Everyday Discrimination Is Associated With Nicotine Dependence Among African American, Latino, and White Smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2014;16(6):633–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Azagba S, Sharaf MF. Binge drinking and marijuana use among menthol and non-menthol adolescent smokers: Findings from the Youth Smoking Survey. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39(3):740–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2002;4(2):149–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]