1. Introduction

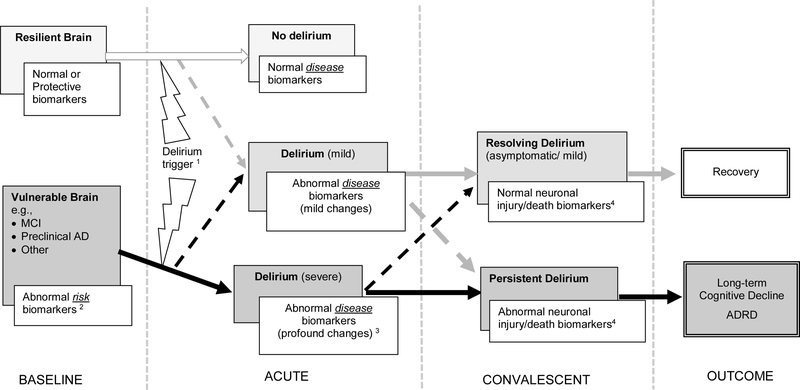

Delirium and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are frequent causes of cognitive impairment among older adults and share a complex relationship in that delirium and AD can occur independently, concurrently, and interactively – for example, delirium can alter the course of an underlying AD. Whether delirium is a marker of vulnerability to AD, unmasks unrecognized AD, accelerates preclinical AD, or itself can cause permanent neuronal damage and lead to AD is poorly understood, and addressing these issues is a high-priority focus in aging research1. In this paper, we propose a novel conceptual model (Figure 1) illustrating how biomarker studies might advance our understanding of the interrelationship of delirium and AD due to neuronal injury. We cite examples of potential neuronal injury biomarkers, their temporal trends, and how they fit within the framework of our model.

Figure 1. Conceptual model for the interrelationship between delirium and AD.

Grey boxes indicate the baseline brain status (far left panel, BASELINE) delirium “state” (middle panels, ACUTE and CONVALESCENT), or outcome (far right panel, OUTCOME); white boxes indicate corresponding (hypothesized) biomarker level. Solid arrows indicate hypothesized pathways for development of delirium (gray),complicated delirium (black), or no delirium (white); dashed arrows indicate where exceptions can occur. 1This figure is intended to represent the most likely pathways for outcomes but there are exceptions. For example, a patient with a resilient brain (upper box, far left panel) could develop a severe delirium, if the delirium trigger was sufficiently noxious (lower box, second panel from left) and ultimately develop long-term cognitive decline or ADRD; likewise someone with a vulnerable brain (lower box, far left) who is resilient to the delirium trigger because of high cognitive reserve might develop a mild delirium (middle box, second panel from left) and go on to recover (upper box, far right panel)

1 Delirium can be triggered by a range of insultsincluding surgery, infections, hypoxia, metabolic abnormalities, stroke, drugs, or anesthetics, and these insults can vary in severity and duration

2 Abnormal risk biomarkers (at baseline) of a vulnerable brain might reflect inflammation, oxidative stress, or chronic neurodegeneration present at basal level

3 Abnormal biomarkers triggered by delirium mightreflect inflammation, alterations in neurotransmitter function, neuronal or microglial dysfunction, or neuronal death, or acceleration of underlying chronic processes. As biomarkers become increasingly abnormal, deliriumseverity may increase as well.

4 Abnormal end product (i.e., neuronal injury/cell death) biomarkers emerge in the convalescent phase when disease processes are sufficient during the acute phase to trigger neuronal injury. Note: This model will accommodate multiple putative biomarkers. For example, anemia can still be integrated into our conceptual model, as a risk or disease marker that is contributory along the pathway to neuronal injury.

abbreviations: AD=Alzheimer’s disease; ADRD=Alzheimer’s disease and relateddementias; LTCD=long-term cognitive decline; MCI=mild cognitive impairment

2. Delirium, Alzheimer’s disease, and their Inter-relationship:

Delirium, an acute decline in cognition and attention, is a common complication of illness, acute trauma, and surgery in older adults, and it has been associated with multiple adverse outcomes including increased morbidity and mortality, falls, decline in cognitive and physical function, and loss of independence. Accordingly, delirium results in longer hospital stays and higher costs to patients, family caregivers, and the healthcare system. Some patients develop long-term cognitive decline after delirium, and delirium significantly increases the risk of incident dementia. Delirium is often unrecognized or mistaken for AD.

In contrast, AD is an insidious neurodegenerative condition characterized by chronic and progressive cognitive decline. The prevalence of delirium among patients with dementia is estimated to range from 22% to 89% of hospitalized and community populations aged 65 and older2. When patients with AD do develop delirium, they are more likely to experience adverse outcomes including death or placement in a nursing facility and accelerated cognitive decline3.

A number of mechanisms for how delirium may contribute to dementia have been proposed, including inflammation, oxidative stress, neuronal dysfunction and acceleration of dementia pathology4. Some insults, such as hypoxia, metabolic derangements or particular drugs (e.g., anticholinergics), may directly cause neuronal dysfunction via alterations in neurotransmitters (e.g., acetylcholine deficiency5 while others, such as inflammation, lead to activation of microglia and astrocytes, then in turn to the production of free radicals, complement factors, glutamate, and nitric oxide6, and ultimately neuronal injury. Building on prior work examining neuroinflammation and these other potential mechanisms, biomarkers of neuronal injury provide a novel link between delirium and AD4 which has not been fully explored.

3. Biomarkers of delirium and AD:

Although not yet used routinely for clinical diagnosis, biomarkers in AD have been employed in large research trials for estimating risk, establishing a diagnosis of preclinical AD or mild cognitive impairment (MCI) due to AD pathology, measuring the progression of AD, and ultimately, for better understanding of the underlying pathophysiology7. In delirium, inflammatory, neurodegenerative, metabolic, and neurotransmitter-based biomarkers3 have been investigated as potential research tools for risk stratification, diagnosis, monitoring, and prognosis, though none have yet been validated for clinical applications, such as diagnosis or monitoring of delirium.

Whereas AD is typically slowly progressive, delirium is a relatively rapid and dynamic syndrome in which biomarker levels may change abruptly in response to an acute stressor or stressors (surgery, infection, etc.). For this reason, a useful model of biomarkers in delirium would include how biomarkers change over time, in order to consider those present before onset of disease (risk biomarker), those altered by disease (disease biomarker), and those reflecting the end product of a disease (outcome biomarker)8. Due to the complex nature of delirium, with its myriad etiologies and protean manifestation, a model of shared delirium and dementia biomarkers would need to accommodate biomarkers that are common among multiple conditions.

Another important consideration for biomarkers of delirium and AD is the biofluid in which the biomarkers are measured. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is thought to accurately represent brain changes but there are challenges to collecting CSF, particularly in delirious patients, over multiple time points, and in large-scale studies. Despite these challenges, there is growing interest in using CSF biomarkers to better understand delirium pathophysiology. Blood-based biomarkers, which are more accessible during acute illness, may also be useful in delirium. With the development of ultra-sensitive immunoassays, protein biomarkers of neurodegeneration (tau) and axonal injury (neurofilament light, NfL) can now be measured in blood, although it remains to be determined whether these correlate with levels in the CSF, particularly in the setting of acute illness when most delirium occurs.

Much effort has been focused on protein biomarkers, which while important, do not tell the whole picture. Other important avenues of future research include emerging blood-based biomarkers such as: 1) exosomal microRNAs (miR), which are small non-coding RNAs that modulate mRNA stability and post-transcriptional gene regulation that often become dysregulated in numerous conditions, including in the pathological process of AD, 2) novel neuronal injury biomarkers, such as those associated with endothelial damage and blood-brain barrier disruption, and 3) unbiased systems biology approaches (genomics, proteomics, lipidomics, and metabolomics). Ultimately, all of these approaches may be useful to explore shared mechanisms that contribute to delirium and AD.

4. Proposed Conceptual Model:

We propose a conceptual model (Figure 1) illustrating how biomarker studies might advance our understanding of the interrelationship of delirium and AD. This model builds on the concept of vulnerability, the degree to which the brain adversely reacts to a stressor, resilience, which we describe as the ability of the brain to withstand and recover from the impact of stressors9, and the severity of the stressor. The model is simplified to represent the most likely pathways. For example, a patient with a resilient brain may be capable of withstanding relatively mild stressors, resulting in no delirium or only a mild delirium with a good chance of full recovery; this same resilient brain when faced with a severe stressor (e.g. a young otherwise healthy patient in the intensive care unit with severe sepsis), may manifest a severe delirium with persistent cognitive symptoms. Conversely, a patient with a vulnerable brain (e.g., a patient with cognitive impairment or an underlying inflammatory state) may need only a mild stressor to precipitate a severe delirium with persistent symptoms.

The model also considers changes in biomarkers over time from baseline, to acute delirium, to convalescence, and then over the long-term. The time course is of critical importance, particularly in delirium which itself fluctuates in terms of clinical presentation and symptom severity. In this model, risk biomarkers reflecting a baseline vulnerability (i.e., inflammation, oxidative stress, or chronic neurodegeneration) may be predictive of delirium incidence and outcome. During the acute phase of delirium, there is an emergence of new disease biomarkers, reflecting diverse processes that might include inflammation, alterations in neurotransmitter function, neuronal or microglial dysfunction, or acceleration of underlying chronic processes. Finally, outcome biomarkers indicating the end-product of disease processes, such as neuronal injury or death, appear after delirium and may persist over the long term. We hypothesize that the occurrence of neuronal injury, as shown in our model, is critical to linking delirium and dementia.

5. Mechanisms and pathophysiology at the Interface of Delirium and AD

Within the framework of our proposed conceptual model (Figure 1), we hypothesize that there are common baseline risk biomarkers and outcome biomarkers for delirium and AD, and that these represent shared mechanisms and pathophysiology. Moreover, biomarkers of AD (which may be either risk markers or disease markers for AD depending on whether or not the AD is symptomatic), could also serve as risk biomarkers for delirium, and thus identify individuals who are vulnerable in the face of stressors to developing delirium. Neuronal injury, as reflected by outcome biomarkers, may represent a final common pathway for disparate pathophysiologic processes that occur during acute delirium. These outcome markers for delirium may serve as risk markers for cognitive decline or AD following an episode of delirium. For example, systemic inflammation may lead to neuronal inflammation which then results in direct neuronal injury10. Thus, longitudinal studies are needed11 and we include this in our conceptual model. In the setting of underlying brain vulnerability, such as neurodegeneration or aging, systemic inflammation may lead to an exaggerated central inflammatory response12, and therefore potentially greater neuronal injury. It may also be possible that in the setting of AD pathology (which again may or may not be clinically symptomatic), neurons are more vulnerable to injury and cell death with even modest levels of neuroinflammation. Whether neuronal injury from delirium can then subsequently initiate or accelerate AD pathology is not known, but we hypothesize that neuronal injury and death is a critical step connecting delirium and AD. Therefore, biomarkers that reflect neuronal injury or death, in addition to biomarkers of AD, may yield important insight into the shared mechanisms between delirium and AD. Below we review selected literature, with a focus on biomarkers reflecting neuronal injury that have been examined in both delirium and AD: 1) AD biomarkers and 2) biomarkers of neuronal injury. We also discuss important issues in designing future biomarker studies.

6. AD biomarkers and delirium:

Reduced CSF levels of amyloid β (Aβ)42 and elevated CSF levels of total tau (T-tau) and phospho-tau (P-tau) compared with controls has been established as an “AD-signature” for diagnosing cognitive impairment due to AD pathology. A recent meta-analysis of biomarker literature in AD and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) supports the association of this CSF AD-signature with AD and MCI13. Elevated levels of CSF T-tau have been described in traumatic brain injury, acute stroke, and other neurodegenerative conditions, and likely reflects the intensity of neurodegeneration and disease progression. Elevated CSF P-tau, a measure of the phosphorylation state of tau appears to be more specific with AD14.

Plasma levels of T-tau correlate poorly with CSF T-tau, however plasma T-tau has been found to be associated with AD. To date, plasma findings have been less reproducible than those in CSF, at least using technology available up to this point14.

Studies of AD biomarkers in delirium have been mixed. Several studies have associated the “CSF-AD signature” described above with delirium. Patients with post-operative delirium have a reduced CSF Aβ42/Tau ratio15 and a recent study16 found patients without dementia who developed delirium had lower CSF Aβ42 levels, higher T-tau levels, and lower ratios of Aβ42 to T-tau and P-tau relative to those without delirium. In contrast, other studies did not find significant differences between preoperative CSF Abeta1β42, tau, and P-tau levels in participants who did and did not develop delirium17.

Another AD-related biomarker that has been examined in delirium is apolipoprotein E (ApoE). Two different aspects of ApoE have been examined, the ApoE genotype, particularly the E4 allele, which has been strongly associated with AD, and absolute levels of the ApoE protein measured in plasma and CSF. The presence of an E4 allele of apolipoprotein E (ApoE) geneotype has been associated with delirium in some studies18, but others did not observe this relationship19,20. In meta-analyses the ApoE E4 allele is associated with longer duration of delirium but not with delirium incidence18. Plasma ApoE levels are reduced in AD21 and it is hypothesized that ApoE plays a role in neuronal maintenance and repair. In patients with delirium, compared to AD, ApoE levels in CSF are even lower during delirium. This study observed no significant differences in ApoE in plasma between AD and delirium, nor did plasma and CSF ApoE levels correlate, suggesting that blood-based ApoE levels do not reflect brain dysfunction in delirium as well as they do in dementia22. Despite the conflicting findings, the potential role of ApoE in the relationship between delirium and dementia remains intriguing and worthy of further investigation.

7. Neuronal Injury/Death Biomarkers in AD and Delirium

7.1. Neuron Specific Enolase (NSE):

Neuron specific enolase (NSE) is one of the five isozymes of the glycolytic enzyme, enolase and is released into the CSF when neural tissue is injured. In dementia, CSF NSE findings have been variable. NSE in the CSF has been shown to be increased in AD23, increased in both AD and vascular dementia24, unchanged in AD25, or reduced in AD26. There were no differences in serum or plasma concentrations of NSE in patients with AD compared to controls in a number of studies13.

NSE has also been examined in delirium, and overall, the findings are also mixed. Compared with participants with dementia, patients with delirium demonstrated lower levels of CSF NSE27. Delirium is associated with higher plasma NSE concentrations and mortality in critically ill patients28. A trend towards an association between persistently elevated plasma NSE levels and cognitive impairment at discharge in patients following cardiopulmonary bypass surgery29 has been reported. Others found no significant difference in plasma NSE between delirium and control groups30.

7.2. S100B

S100B is a calcium-binding protein secreted by astrocytes that is released from injured cells into the bloodstream and has been proposed as a marker of the acute phase of brain damage, blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability, and serious central nervous system (CNS) injury. S100B serum levels are high during inflammation, and after trauma or surgery. Among patients with AD, some studies report higher CSF levels of S100B in AD patients compared to controls31, and other studies report that S100B levels correlate with AD disease severity (Clinical Dementia Rating or Mini Mental State Exam score)25. Others have found higher CSF S100B levels in mild-to moderate AD, which then decreased as the disease worsened32.

There is significant literature examining the association of S100B with delirium or outcomes after delirium. A number of studies have shown high plasma S100B levels in delirium33,34 or elevated CSF S100B levels measured at the time of hip fracture surgery in patients with delirium vs. without delirium35. In keeping with these observations, a low concentration of S100B has been proposed to be used as a risk stratification marker to rule out delirium36. However, there are studies that did not detect any difference in plasma S100B levels in patients with and without cognitive impairment following cardiopulmonary bypass28,29, or found that CSF S100B levels were lower in patients with persistent delirium compared to those with probable AD27. A recent study of older hip fracture patients found serum S100B was not associated with postoperative delirium, and although S100B was associated with cognitive decline or death in the first year after hip fracture, this was observed only in participants without perioperative delirium37.

7.3. Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)

Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) is expressed by astrocytes and is used as a marker of astrocytosis in neurodegeneration. CSF concentration of GFAP has been shown to be elevated in AD, as well as in other neurodegenerative dementias38 though other studies found no difference between AD and controls or between AD and other neurodegenerative conditions39. GFAP has not been demonstrated to be increased in delirium40.

7.4. Brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)

Brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) functions to help support neuron survival and encourage the growth and differentiation of new neurons and synapses. Advanced age and low education has been associated with decreased serum BDNF levels, with the lowest levels in patients with AD, which also corresponded to the severity of cognitive impairment41. Others have observed that at early stages of AD, BDNF significantly increased in comparison to control groups although levels then declined in later stages of the disease whereas another study found no change in BDNF42. BDNF has been found to be elevated in delirium in one study28 and not elevated compared with controls in another study43. BDNF has not yet been studied as a resilience factor following an episode of delirium, which would correspond to its putative physiological role.

7.5. Neurofilament light (NfL)

Neurofilament light (NfL), is intermediate filament protein that is expressed in neurons and believed to function primarily to provide structural support for the axon44. NfL is a general marker of neuronal injury and neurodegeneration and has also been detected in CSF and blood in multiple conditions including stroke, traumatic brain injury, multiple sclerosis, progressive supranuclear palsy, and frontotemporal dementia. In AD, serum NfL has been shown to be increased in AD and MCI patients compared to controls, with the highest serum levels in cases with positive amyloid PET scans. Serum NfL also correlated with poorer cognition and greater changes in neuroimaging45. In the CSF, NfL has been shown to predict neurodegeneration in older adults with very low AD risk. To date, NfL has not been examined in delirium.

7.6. Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1)

Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase (UCH-L1) is an imporatant component of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), which functions to remove and degrade misfolded proteins. Impairment of the UPS results in the accumulation of mis-folded proteins in the cell, and a decrease in UCH-L1 activity has associated with Parkinson’s and AD. UCH-L1 is found in neuronal cell bodies and is thought to be a highly specific marker of neuronal injury. UCH-L1 can be detected in CSF and serum in patients with traumatic brain injury, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, and seizures46. Post-mortem studies of brains from patients with sporadic AD show a down-regulation of UCH-L147. In TBI UCH-L1 levels are increased within one hour48. Despite this potential promise as a neuronal injury biomarker, UCH-L1 has not been examined in any large dementia or delirium studies.

8. Micro RNA as potential biomarkers for delirium

MicroRNAs (miR) are small non-coding RNAs that regulate the expression of mRNAs post-transcriptionally by inhibiting translation or degradation of their mRNA targets. Abnormal expression of miRNAs has been observed in diverse disease and altered physiological states49. While most miRNA are found intracellularly, circulating miRNA or extracellular miRNA, have also been detected in different biofluids, including serum and plasma, and as such hold potential as biomarkers in aging and age-related disorders50 Circulating miRNA are believed to be released and then protected from extracellular degradation through transport via exosomes (cell-derived extracellular vesicles), microvesicles, and other mechanisms49. Freely circulating disease-specific or dysregulated miRs have been linked to pathogenic states50.

In AD, miRNA have been investigated in blood, serum, serum or plasma exosomes, and CSF, and are both upregulated and down regulated (for review, see 50). Studies have suggested that miRNAs serve as critical regulators in signaling pathways such as in amyloid metabolism, tau pathology, neuroinflammation, and apoptosis. Dysregulated miRs may influence gene transcription, protein expression and induce the spread of neurodegeneration51. The most consistently dysregulated miRNA markers for AD include miR-29b, miR-181c miR-15b, miR-146a, and miR-107 where uniform results have been observed in at least two independent studies52

In delirium, a recent pilot study53 among older patients who underwent total knee or hip replacement under spinal anesthesia, several miRs (miR-146a, miR-125b, and miR-181c) known to modulate both neuronal and immune processes were examined. Among patients who developed delirium, an up-regulation of miR-146a and miR-181c in CSF and down-regulation of miR-146a in the serum was observed. Additionally, lower CSF miR-146a and lower CSF/serum miR-146a ratios were significantly associated with milder delirium severity. Taken together, these findings support a potential role for miRs as delirium risk, disease, or end product biomarkers. miRNA’s may likewise contribute to our understanding of shared delirium and dementia pathophysiology.

9. Discussion: Recommendations for Future Research

Understanding the interface between delirium and AD is a high-priority focus of aging research. Biomarkers can play important roles in confirming diagnosis, measuring severity, and stratifying risk, and may also be used to achieve a greater understanding of shared pathophysiology between delirium and AD and ultimately to find more effective treatment strategies. Biomarkers shared by both delirium and AD are potential “linkage” points whereby one condition may influence the other, and could potentially explain for example, how delirium accelerates the rate of cognitive decline in patients with AD.

Biomarkers of AD pathology and neuronal injury have been found in both delirium and AD (Table 1), however the results across studies have been somewhat inconsistent. This in part may be due to study design, for example the use of small sample sizes and cross-sectional designs54. For logistical reasons, CSF biomarker studies frequently rely on collecting CSF at the time of surgery, which can limit the patient population to those undergoing emergency surgery for acute hip fracture or other procedures performed under spinal anesthesia. Other methodologic issues include a lack of standardization of biomarker sample collection, processing, storage, and assays across labs, or lack of quality control of assays within labs.

Table 1.

Summary of Selected Biomarkers at the Interface of Delirium and Dementia

| Biomarker | Fluid | Biomarker level in Dementia |

Biomarker level in Delirium |

Biomarker level in Other Neurological Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer’s disease (AD) associated biomarkers | ||||

| amyloid β (Aβ)42 | CSF | Decreased | Decreased (some studies) | |

| t-Tau | CSF | Increased | Increased (some studies) | Increased in TBI, stroke, neurodegeneration |

| p-Tau | CSF | Increased (specific for AD dx) | Unchanged | |

| p-Tau | Plasma | Poor correlation with CSF t-tau but increased levels associated with AD | NA | |

| ApoE geneotype | plasma | Strong association | Inconsistent association | |

| ApoE level | CSF | Decreased | ||

| ApoE level | Plasma | Decreased | Does not correlate with CSF levels | |

| Neuronal Injury/Death Biomarkers | ||||

| BDNF | Plasma | Increase then decrease/variable | Increased/ variable | |

| GFAP | CSF | Increased/variable | Not increased | |

| NfL | CSF | Increased | NA | Increased in Stroke, TBI, MS, PSP, FTD |

| NfL | Plasma | Increased | NA | Increased after surgery and anesthesia |

| NSE | CSF or plasma | Variable | Variable | |

| S100B | CSF | Increased, then decreased in later stages of disease | Increased/variable | Increased with trauma, surgery, or inflammation |

| S100B | Plasma | NA | Increased/variable | |

| UCH-L1 | CSF or plasma | Increased (limited studies) | NA | Increased in PD, TBI, HIE, seizures |

| microRNA | ||||

| miR | CSF | miR-29a, miR-125b (upregulated); miR-146a (downregulated) | miR-125b, miR-146a, miR-181c (upregulated) | |

| miR | Plasma | miR-146a (upregulated); miR-29b, miR-181c, miR-15b, miR-107 (downregulated) | miR-146a (downregulated) | |

ApoE=apolipoprotein E; BDNF=brain derived neurotrophic factor; CSF= cerebrospinal fluid; FTD= frontotemporal dementia; GFAP= Glial fibrillary acidic protein; HIE= hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy; miR= microRNA; MS= multiple sclerosis; NA= no published reports; NfL= Neurofilament Light; NSE = neuron specific enolase; PSP= progressive supranuclear palsy; TBI= traumatic brain injury; UCH-L1= Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase L1

Specific issues should be considered when designing a study targeted towards biomarker discovery at the interface between delirium and AD (Table 2). Studies will need to be conducted in multiple, large-scale multi-center cohorts including diverse clinical populations to validate and assure generalizability of the findings. Careful inclusion/exclusion criteria, and detailed baseline assessment can help ensure the appropriateness of the control group. Matched case-control studies may be more feasible and efficient, particularly if resources are limited. Biomarkers for delirium are likely to include both static baseline risk markers as well as dynamic disease biomarkers that fluctuate over the course of the delirium episode and recovery period. Careful consideration will need to be made for which time points delirium, cognitive function, and/or biomarkers will be measured in the study; the temporal relationship between biomarkers and the course of delirium – including the time before, during, and after the delirium episode - will be critical in understanding at which point(s) delirium may connect with dementia.

Table 2.

Checklist for Biomarker Studies Examining the Interface Between Delirium and AD

| Section/Topic | Questions to Address |

|---|---|

| Study Design | What is the optimal study design to maximize biomarker discovery? Who should be included in the study population? Are exclusion and inclusion criteria well defined and justified? Is an appropriate control group included? Are credible sample size calculations performed on main study hypotheses, such that adequate number of participants are enrolled? Which time points will delirium, cognitive function, and/or biomarkers be measured? Is there an intervention as part of the study? If so, is the intervention double-blinded? |

| Assessment of Methods | What instruments will be used to measure delirium and delirium severity? What instruments will be used to measure baseline cognitive function? What methods will be used to diagnose AD and AD severity? Are instruments standardized and validated? How will biomarkers be collected (blood, CSF)? |

| Outcomes | Which outcomes are most relevant – delirium incidence and severity? Cognitive function? Incident MCI or AD? ( i.e. is the potential biomarker being examined as a risk, disease, or outcome biomarker?) |

| Data Analysis | Has a biostatistician been consulted to advise on the project? What analytic approach is optimum? What is the expected attrition for the study, and is this realistic? How will missing data and nonresponses be handled? Are there weaknesses in the study design that will compromise the data analysis? How will potential confounding be controlled (design/analysis)? Consideration of biological variables of interest, such as sex-stratification |

| Validation Reproducibility of Findings | Is there independent validation of findings? What methods will be used? Split sample, independent sample?, etc. |

| Summary | What is the clinical relevance of the findings? What additional steps are required before the biomarkers can be applied to clinical care? |

Carefully characterized clinical phenotypes are essential for effective biomarkers studies. Consistent use of validated delirium measures is a must and both the occurrence and severity of delirium should be measured. Baseline cognitive function should be assessed and included in the analysis. If AD is used as inclusion criteria, how AD will be characterized in the study – i.e., using a reference standard, clinical criteria, AD imaging or CSF biomarkers, an expert consensus panel, or a combination thereof – should also be considered.

Biomarker discovery generally takes one of two general approaches – either hypothesis-derived screening of candidate biomarkers, or broad-based laboratory screens. A particular advantage of multiplex assays is the identification of hundreds to thousands of proteins from a single sample across a wide assay dynamic range (pg/mL to ng/mL), with reasonable sensitivity, reproducibility, and high throughput. Examination of biomarkers over time is critical given the dynamic nature of delirium, as evidenced by the observation that IL-6 change over time in patients with delirium54,55. In addition, due to the fluctuating and changing time course of delirium, ideally biomarkers should be measured at multiple time points, to understand how biomarkers levels align with the course of delirium (e.g., its onset, peak, duration, and resolution).

As delirium and AD often affect frail and medically complex older adults, attrition should be anticipated. Data analysis must consider possible flaws in the study design, confounding factors, and handling missing data. Lastly, standardization of assay platforms across laboratories, and careful quality control within laboratories will allow for comparisons across studies.

10. Limitations

Because this review is focused on biomarkers reflecting neuronal injury, a number of putative biomarkers shared between delirium and dementia were not discussed. It is likely that there are multiple mechanisms (and biomarkers) that are involved in the interface between delirium and dementia and unfortunately it is not possible to include all within this review. However, other putative biomarkers can still be integrated into our conceptual model, as risk or disease markers that are contributory along the pathway to neuronal injury. For example, although the association of C-reactive protein and dementia has been mixed56, CRP has been shown, as defined in our model, to be a baseline (risk biomarker) IL-6 to be an acute phase (disease biomarker)55,56 in delirium. Anemia and hypoproteinemia are considered to be precipitating factors for delirium and anemia been associated with dementia57, and lowered levels of melatonin are associated with MCI and delirium58 all could fit into our model as biomarkers reflecting brain vulnerability (i.e., risk biomarkers).

11. Conclusions

Delirium and AD have been closely linked epidemiologically, yet the pathophysiology underlying this relationship remains largely unknown, and under-explored. Examining established biomarkers of AD in delirium studies, and emerging biomarkers of neuronal injury and microRNA’s in both studies of delirium and AD, may help to shed light on the shared, complex pathophysiology underlying both syndromes. Careful consideration of study design including eligibility criteria, rigorous measurement of delirium, AD, and the biomarkers of interest, and sophisticated analytic strategies to address confounding and attrition, will be important to achieve these goals. Through improved understanding of the pathophysiology of delirium and AD derived from such studies, interventions can be designed to reduce the impending epidemic of late-life cognitive impairment.

Key points:

The interrelationship between delirium and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is complex and poorly understood.

Advances in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood-based biomarkers, including development of ultra-sensitive immunoassays to measure protein biomarkers, and novel biomarkers such as exosomal microRNA, may lead to discovery of biomarkers common to delirium and AD, potentially representing shared pathophysiology.

We propose a conceptual model illustrating how biomarker studies might advance our understanding of the interrelationship of delirium and AD.

Important issues in designing future biomarker studies include careful consideration of study design, sophisticated statistical analytic strategies, and standardization of assay platforms.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This manuscript was funded by R21AG057955(TGF), P01AG031720 (SKI), R24AG054259 (SKI), K07AG041835 (SKI), R01AG051658 (ERM), K24AG035075 (ERM), and K01AG057836 (SMV) from the National Institute on Aging, UL1TR001102–04S2 (TGF) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the Alzheimer’s Association AARF-18–560786 (SMV) and a Marcus Applebaum Pilot grant from the family of Beth and Richard Marcus (TGF). Dr. Inouye holds the Milton and Shirley F. Levy Family Chair at Hebrew SeniorLife/Harvard Medical School.

Literature Cited

- 1.Oh ES, Fong TG, Hshieh TT, Inouye SK. Delirium in Older Persons: Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment. JAMA. 2017;318(12):1161–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fick DM, Agostini JV, Inouye SK. Delirium superimposed on dementia: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(10):1723–1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oh ES, Fong TG, Hshieh TT, Inouye SK. Delirium in Older Persons: Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment. JAMA. 2017;318(12):1161–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fong TG, Davis D, Growdon ME, Albuquerque A, Inouye SK. The interface between delirium and dementia in elderly adults. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(8):823–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hshieh TT, Fong TG, Marcantonio ER, Inouye SK. Cholinergic deficiency hypothesis in delirium: a synthesis of current evidence. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(7):764–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simone MJ, Tan ZS. The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of delirium and dementia in older adults: a review. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2011;17(5):506–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henriques AD, Benedet AL, Camargos EF, Rosa-Neto P, Nobrega OT. Fluid and imaging biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease: Where we stand and where to head to. Exp Gerontol. 2018;107:169–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marcantonio ER, Rudolph JL, Culley D, Crosby G, Alsop D, Inouye SK. Serum biomarkers for delirium. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61 (12): 1281–1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karatsoreos IN, McEwen BS. Resilience and vulnerability: a neurobiological perspective. F1000Prime Rep. 2013;5:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marcantonio ER. Postoperative delirium: a 76-year-old woman with delirium following surgery. JAMA. 2012;308(1):73–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cerejeira J, Firmino H, Vaz-Serra A, Mukaetova-Ladinska EB. The neuroinflammatory hypothesis of delirium. Acta Neuropathologica. 2010;119(6):737–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cortese GP, Burger C. Neuroinflammatory challenges compromise neuronal function in the aging brain: Postoperative cognitive delirium and Alzheimer’s disease. Behav Brain Res. 2017;322(Pt B):269–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olsson B, Blennow K, Zetterberg H. The clinical value of fluid biomarkers for dementia diagnosis - Authors’ reply. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(12):1204–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zetterberg H. Review: Tau in biofluids - relation to pathology, imaging and clinical features. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2017;43(3):194–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie Z, Swain CA, Ward SA, et al. Preoperative cerebrospinal fluid beta-Amyloid/Tau ratio and postoperative delirium. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2014;1 (5):319–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Idland AV, Wyller TB, Stoen R, et al. Preclinical Amyloid-beta and Axonal Degeneration Pathology in Delirium. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;55(1):371–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Witlox J, Kalisvaart KJ, de Jonghe JF, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid beta-amyloid and tau are not associated with risk of delirium: a prospective cohort study in older adults with hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(7):1260–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Munster BC, Korevaar JC, Zwinderman AH, Leeflang MM, de Rooij SE. The association between delirium and the apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 allele: new study results and a meta-analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(10):856–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oldenbeuving AW, de Kort PL, Kappelle LJ, van Duijn CM, Roks G. Delirium in the acute phase after stroke and the role of the apolipoprotein E gene. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21 (10):935–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vasunilashorn S, Ngo L, Kosar CM, et al. Does Apolipoprotein E Genotype Increase Risk of Postoperative Delirium? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23(10):1029–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koffie RM, Hashimoto T, Tai HC, et al. Apolipoprotein E4 effects in Alzheimer’s disease are mediated by synaptotoxic oligomeric amyloid-beta. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 7):2155–2168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caplan GA, Tai J, Hanizan Mohd F, McVeigh CL, Hill MA, Poljak A. Cerebrospinal Fluid Apolipoprotein E Levels in Delirium. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 2017;7(2):240–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt FM, Mergl R, Stach B, Jahn I, Gertz HJ, Schonknecht P. Elevated levels of cerebrospinal fluid neuron-specific enolase (NSE) in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2014;570:81–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blennow K, Wallin A, Ekman R. Neuron specific enolase in cerebrospinal fluid: a biochemical marker for neuronal degeneration in dementia disorders? J Neural Transm Park Dis Dement Sect. 1994;8(3):183–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chaves ML, Camozzato AL, Ferreira ED, et al. Serum levels of S100B and NSE proteins in Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Neuroinflammation. 2010;7:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cutler NR, Kay AD, Marangos PJ, Burg C. Cerebrospinal fluid neuron-specific enolase is reduced in Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol. 1986;43(2):153–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caplan GA, Kvelde T, Lai C, Yap SL, Lin C, Hill MA. Cerebrospinal fluid in long-lasting delirium compared with Alzheimer’s dementia. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65(10):1130–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grandi C, Tomasi CD, Fernandes K, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neuron-specific enolase, but not S100beta, levels are associated to the occurrence of delirium in intensive care unit patients. J Crit Care. 2011;26(2):133–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baranyi A, Rothenhausler HB. The impact of S100b and persistent high levels of neuron-specific enolase on cognitive performance in elderly patients after cardiopulmonary bypass. Brain Inj. 2013;27(4):417–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Munster BC, Korse CM, de Rooij SE, Bonfrer JM, Zwinderman AH, Korevaar JC. Markers of cerebral damage during delirium in elderly patients with hip fracture. BMC Neurol. 2009;9:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petzold A, Jenkins R, Watt HC, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid S100B correlates with brain atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2003;336(3):167–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peskind ER, Griffin WS, Akama KT, Raskind MA, Van Eldik LJ. Cerebrospinal fluid S100B is elevated in the earlier stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Int. 2001;39(5–6):409–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Munster BC, Bisschop PH, Zwinderman AH, et al. Cortisol, interleukins and S100B in delirium in the elderly. Brain Cogn. 2010;74(1):18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Munster BC, Korevaar JC, Korse CM, Bonfrer JM, Zwinderman AH, de Rooij SE. Serum S100B in elderly patients with and without delirium. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(3):234–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hall RJ, Ferguson KJ, Andrews M, et al. Delirium and cerebrospinal fluid S100B in hip fracture patients: a preliminary study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(12):1239–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Al Tmimi L, Van de Velde M, Meyns B, et al. Serum protein S100 as marker of postoperative delirium after off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery: secondary analysis of two prospective randomized controlled trials. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2016;54(10):1671–1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beishuizen SJ, Scholtens RM, van Munster BC, de Rooij SE. Unraveling the Relationship Between Delirium, Brain Damage, and Subsequent Cognitive Decline in a Cohort of Individuals Undergoing Surgery for Hip Fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(1):130–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ishiki A, Kamada M, Kawamura Y, et al. Glial fibrillar acidic protein in the cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. J Neurochem. 2016;136(2):258–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosen C, Mattsson N, Johansson PM, et al. Discriminatory Analysis of Biochip-Derived Protein Patterns in CSF and Plasma in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front Aging Neurosci. 2011;3:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cape E, Hall RJ, van Munster BC, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid markers of neuroinflammation in delirium: a role for interleukin-1beta in delirium after hip fracture. J Psychosom Res. 2014;77(3):219–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siuda J, Patalong-Ogiewa M, Zmuda W, et al. Cognitive impairment and BDNF serum levels. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2017;51(1):24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laske C, Stransky E, Leyhe T, et al. BDNF serum and CSF concentrations in Alzheimer’s disease, normal pressure hydrocephalus and healthy controls. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41 (5):387–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brum C, Stertz L, Borba E, Rumi D, Kapczinski F, Camozzato A. Association of serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) with diagnosis of delirium in oncology inpatients. Braz J Psychiatr. 2015;37(3):197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Idland AV, Sala-Llonch R, Borza T, et al. CSF neurofilament light levels predict hippocampal atrophy in cognitively healthy older adults. Neurobiol Aging. 2017;49:138–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mattsson N, Andreasson U, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I. Association of Plasma Neurofilament Light With Neurodegeneration in Patients With Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(5):557–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang KK, Yang Z, Sarkis G, Torres I, Raghavan V. Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-L1 (UCH-L1) as a therapeutic and diagnostic target in neurodegeneration, neurotrauma and neuro-injuries. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2017;21(6):627–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Choi J, Levey AI, Weintraub ST, et al. Oxidative modifications and down-regulation of ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase L1 associated with idiopathic Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(13):13256–13264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones A, Jarvis P. Review of the potential use of blood neuro-biomarkers in the diagnosis of mild traumatic brain injury. Clin Exp Emerg Med. 2017;4(3):121–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sohel MH. Extracellular/Circulating MicroRNAs: Release Mechanisms, Functions and Challenges. Achievements in the Life Sciences. 2016;10(2):175–186. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kumar S, Vijayan M, Bhatti JS, Reddy PH. MicroRNAs as Peripheral Biomarkers in Aging and Age-Related Diseases. Prog Mol Biol Transl, Sci. 2017;146:47–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schonrock N, Matamales M, Ittner LM, Gotz J. MicroRNA networks surrounding APP and amyloid-beta metabolism--implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Neurol. 2012;235(2):447–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu HZ, Ong KL, Seeher K, et al. Circulating microRNAs as Biomarkers of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;49(3):755–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dong R, Sun L, Lu Y, Yang X, Peng M, Zhang Z. NeurimmiRs and Postoperative Delirium in Elderly Patients Undergoing Total Hip/Knee Replacement: A Pilot Study. 2017(1663–4365 (Print)). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Khan BA, Zawahiri M, Fau - Campbell NL, Campbell Nl, Fau - Boustani MA, Boustani MA Biomarkers for delirium--a review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(Suppl 2):S256–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vasunilashorn SM, Dillon ST, Inouye SK, et al. High C-Reactive Protein Predicts Delirium Incidence, Duration, and Feature Severity After Major Noncardiac Surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(8):e109–e116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gong C, Wei D, Wang Y, et al. A Meta-Analysis of C-Reactive Protein in Patients With Alzheimer’s Disease. Am, J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2016;31(3):194–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hong CH, Falvey C, Harris TB, et al. Anemia and risk of dementia in older adults: findings from the Health ABC study. Neurology. 2013;81(6):528–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alagiakrishnan K. Melatonin based therapies for delirium and dementia. Discov Med. 2016;21(117):363–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]