Abstract

Objective

One in three veterans will dropout from trauma-focused treatments for PTSD. Social environments may be particularly important to influencing treatment retention. We examined the role of two support system factors in predicting treatment dropout: social control (direct efforts by loved ones to encourage veterans to participate in treatment and face distress) and symptom accommodation (changes in loved ones’ behavior to reduce veterans’ PTSD-related distress).

Method

Veterans and a loved one were surveyed across four VA hospitals. All veterans were initiating Prolonged Exposure therapy or Cognitive Processing Therapy (n = 272 dyads). Dropout was coded through review of VA hospital records.

Results

Regression analyses controlled for traditional, individual-focused factors likely to influence treatment dropout. We found that, even after accounting for these factors, veterans who reported their loved ones encouraged them to face distress were twice as likely to remain in PTSD treatment than veterans who denied such encouragement.

Conclusions

Clinicians initiating trauma-focused treatments with veterans should routinely assess how open veterans’ support systems are to encouraging veterans to face their distress. Outreach to support networks is warranted to ensure loved ones back the underlying philosophy of trauma-focused treatments.

Keywords: PTSD, social control, accommodation, evidenced based treatments, dropout

Trauma-focused treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) result in clinically significant symptom relief for many patients (IOM, 2007). The consistency and strength of evidence supporting their efficacy led to the recommendation of their use as first-line treatments (Management of Post-Traumatic Stress Working Group, 2017). The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has committed considerable time and resources to ensure that two such therapies, Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) and Prolonged Exposure (PE), are widely available (Karlin et al., 2010). Despite the promise of these interventions, initiation rates among veterans with PTSD at VA facilities is low (Shiner et al., 2013), and an important minority of those who begin these psychotherapies fail to complete treatment (e.g., Eftekhari, Ruzek, Crowley, Rosen, Greenbaum, & Karlin, 2013).

Dropout is not a problem unique to trauma-focused treatments (TFTs; Fernandez, Salem, Swift, & Ramtahal, 2015; Hembree, Foa, Dorfan, Street, Kowalski, & Tu, 2003; Imel, Laska, Jakupcak, & Simpson, 2013). Improving adherence is a long-identified priority for research and real-world use of psychotherapies, broadly (e.g., Pekarik, 1986; Weirzbicki & Pekarik, 1993). For cognitive-behavioral therapies, including TFTs, meta-analysis indicates the average dropout rate is 35%, with the highest rates found for depression and substance use disorders (Fernandez et al., 2015). Meta-analysis has also demonstrated that TFTs are not associated with uniquely higher rates of dropout than non-trauma focused PTSD treatments (Imel et al., 2013). A precise estimate of TFT dropout within VA hospitals is unknown. However, published estimates from individual VA facilities converge around 35% (e.g., Chard, Schumm, Owens, & Cottingham, 2010; Kehle-Forbes, Meis, Spoont, & Polusny, 2016; Schnurr et al., 2007; Surís, Link-Malcom, Chard, Ahn, & North, 2013; Thorp, Stein, Jeste, Patterson, & Wetherell, 2012).

Social environments may be particularly important to understanding TFT dropout. PTSD is a disorder with a dramatic impact on social and family relationships (Monson, Taft, & Fredman, 2009). Studies have found these relationships can facilitate or impede entry into mental health care for veterans with PTSD (Meis, Barry, Erbes, & Polusny, 2010; Sayer, Friedman-Sanchez, & Spoont et al., 2009; Spoont et al., 2014) and predict PTSD treatment response (Evans, Cowlishaw, & Hopwood, 2009; Tarrier, Sommerfield, & Pilgrim, 1999). Yet, when and how family relationships influence PTSD treatment dropout remains unknown. We examined two support system factors: social control and PTSD symptom accommodation.

Social Control

The construct of social control was originally developed within sociology to describe how communities influence individual behavior through social expectations and laws; it has been adapted to dyadic relationships (Craddock, van Dellen, Novak, & Ranby, 2015). The construct includes indirect and direct social control (Umberson, 1987). Indirect social control refers to one’s efforts at behavior change intended to please a loved one that are not necessarily requested by the loved one (e.g., quit drinking for one’s children). Direct social control has received more attention and is the focus of the present study. Direct social control (referred to here forward as social control) includes overt efforts by a support system member, urging a person to increase or decrease a targeted behavior (Craddock et al., 2015; Umberson, 1987).

Social control has yet to be examined as a predictor of psychotherapy dropout, but is linked to a variety of health behaviors including, broad increases in healthy behavior (Lewis & Rook, 1999; Tucker, 2002; Tucker & Anders, 2001; Umberson, 1992), lower smoking rates (Westmaas, Wild, & Ferrence, 2002), and better adherence to medical regimes (knee surgery patients, Fekete, Stephens, Druley, & Greene, 2006; osteoarthritis patients; Stephens, Fekete, Franks, Rook, Druley, & Greene, 2009). Paradoxically, Franks, Stephens, Rook, Franklin, Keteyian, & Artinian (2006) found social control is also associated with poorer medical regime adherence among cardiac rehab patients. Additionally, weak and inconsistent associations between social control and health behavior are found (prostate cancer patients, Helgeson, Novak, Lepore, & Eton, 2004; elderly individuals in the community; Rook, Thuras, & Lewis, 1990).

The inconsistency in findings may reflect heterogeneity in how social control attempts are delivered and subjectively experienced by the patient. Social control can be experienced as supportive persuasion, coming from a place of caring and concern (‘positive’ social control), but these tactics can also take the form of criticism, arguing, and nagging (‘negative’ social control; Lewis & Butterfield, 2005). Negative social control can elicit feelings that one’s personal choices and freedoms are restricted, prompting the person do the opposite of what the loved one desired (i.e., psychological reactance, Brehm, 1966). A recent meta-analysis found the overall effect between social control and health behavior varied by the type of social control, with positive tactics associated with more healthy behavior (d = 0.31); negative tactics were associated with less healthy behavior (d = −0.08) and greater ‘backfiring’ (d = 0.65; doing the opposite or hiding the behavior; Craddock et al., 2015).

The effectiveness of a loved one’s control efforts, including the degree to which they are perceived as positive or negative (persuasion versus nagging), may depend on the quality of the dyad’s relationship. Cutrona, Cohen, and Igram (1990) found that greater closeness between the individual receiving and the individual providing support was associated with greater satisfaction with support received. Among prostate cancer patients, Knoll, Burkert, Scholz, Roigas, and Gralla (2012) found social control was associated with greater medical adherence for patients in more satisfied relationships. Similarly, Tucker (2002) found that, among older adults, social control was associated with more hiding unhealthy behaviors and more negative affect for those with a high degree of relationship strain. Consequently, we anticipate that social control will be most effective at reducing TFT dropout when veterans are in well-adjusted relationships.

To examine social control in the context of TFT dropout, appropriate targets of social control must be established. We propose that TFT adherence may be greatest among those who are encouraged by loved ones to attend treatment and to embrace the philosophy of change underlying the treatment. TFTs, such as CPT and PE, encourage participants to explore and approach traumatic material and develop a mastery over their traumatic memories to take back control of their lives (IOM, 2007). Both interventions conceptualize PTSD as a disorder of avoidance and focus on facing versus avoiding trauma-related distress. Consequently, we anticipate that social control tactics important to completing TFTs likely include encouraging veterans to (a) get into or stay in mental health treatment and (b) confront avoided distress.

Accommodation

PTSD symptom accommodation refers to changes in a loved one’s behavior to prevent or reduce PTSD-related distress, such as helping a veteran avoid stressful trauma reminders (Fredman, Vorstenbosch, Wagner, Macdonald, & Monson, 2014). This is like the construct of enabling in the substance use literature in that the loved one inadvertently insulates the symptomatic person from the consequences of his or her disorder-related behavior. With PTSD, a loved one’s efforts to help the veteran avoid can communicate, intentionally or unintentionally, that the loved one believes that approaching trauma reminders is dangerous, the veteran cannot tolerate TFT, and/or TFT is not worth the veteran’s efforts.

Accommodation predicts poor response to treatment for substance use (i.e., enabling behaviors; Rotunda & Doman, 2001) and anxiety disorders (Thompson-Hollands, Edson, Tompson, & Comer, 2014). A meta-analysis of family inclusive treatments for OCD found that interventions focused on accommodative behaviors resulted in better patient improvement than family inclusive treatments without an accommodation focus (Thompson-Hollands et al., 2014). Pukay-Martin and colleagues (2015) found that couple therapy for PTSD reduced accommodation, while another study found that patients with greater family accommodation may be particularly likely to benefit from couple therapy for PTSD (Fredman, Pukay-Martin, Macdonald, Wagner, Vorstenbosch, & Monson, 2016). To the best of our knowledge, this prior work has not examined the role of accommodation in predicting treatment dropout.

For the present study, we are interested in how symptom accommodation and social control influence TFT dropout. We anticipate associations will vary with relationship strain. Importantly, we hope to determine if these factors persist in predicting dropout, after accounting for more traditional, individual-focused factors likely to influence treatment dropout, such as veteran attitudes about TFTs, practical barriers to participation, therapeutic alliance, and PTSD symptom severity. Establishing that support systems influence TFT dropout, even after considering such individual-factors, is essential to elevating the salience clinicians and researchers give support systems when trying to understand treatment dropout.

Method

Participants

Veterans initiating a TFT for PTSD (PE or CPT) across four VA hospitals were mailed study surveys using a repeated mail protocol described below (Dillman, Smyth, & Christian, 2014). Veterans were asked to nominate a close friend, significant other, or family member to complete a similar survey by mail. Veteran survey responders differed from non-responders in that veteran responders were significantly older (responder M = 48.52, SD = 14.0; non-responder M = 38.9, SD = 12.1, F = 1.33, p = .003) and less likely to be Post-911 veterans (46.3%) versus veterans from other conflicts (69.1%), χ2 (1, n = 895) = 49.58, p < .001. Women were also more likely to respond to surveys (67.3% of women responded versus 57.5% of men responded), χ2 (1, n = 895) = 5.50, p = .019. No significant differences between responders and non-responders were found on race, χ2 (4, n = 987) = 2.92, p = .571, or mental health diagnoses in veterans’ medical records, χ2 (1, ns = 987–928) = 2.42–0.02, p = .120–895.

Analyses were limited to veterans who completed their surveys (1) after attending at least one session of treatment, as many variables required knowledge of the treatment, and (2) before completing an adequate dose of treatment (8 sessions). Of the 505 veterans returning surveys in this window of time, 272 loved ones also returned surveys, yielding a final n for our analyses of 272 dyads (544 participants). See Table 1 for characteristics of the sample.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants

| Characteristic | Veteran | Loved one |

|---|---|---|

| N | 272 | 272 |

| Age, M (SD) | 47.7 (13.9) | 46.8 (14.6) |

| Gender | ||

| Women | 20.6 | 80.7 |

| Men | 79.4 | 18.9 |

| Transgender | -- | 0.4 |

| Race (%) | ||

| White | 62.7 | 69.5 |

| Black | 19.6 | 14.8 |

| Native American | 2.6 | 1.9 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander/Hawaiian | 4.4 | 3.5 |

| Hispanic ethnicity (yes; %) | 10.7 | 10.1 |

| Income (%) | ||

| less than $20,000 | 16.5 | 19.5 |

| $20–40,000 | 36.0 | 24.1 |

| $40,000–60,000 | 21.8 | 21.4 |

| $60,000–80,000 | 10.3 | 17.2 |

| $80,000–100,000 | 7.7 | 10.3 |

| Greater than $100,000 | 7.7 | 7.6 |

| Education (%) | ||

| Less than a high school diploma | 1.1 | 2.6 |

| High school graduate or equivalent | 14.4 | 19.0 |

| Some college | 36.2 | 29.0 |

| Associates or technical degree | 18.8 | 18.6 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 20.3 | 19.7 |

| Post-graduate degree | 9.2 | 11.2 |

| Relationship to veteran (%) | ||

| Intimate partners | 77.5 | |

| Friend | 6.3 | |

| Mother/father | 5.9 | |

| Adult child (over age 18) | 5.2 | |

| Brother/sister | 2.2 | |

| Other family member | 1.9 | |

| Former (‘ex’) intimate partner | 1.1 | |

| Deployment Era (%) | ||

| Post-911 (OEF/OIF/OND/War on Terror) | 49.6 | |

| Vietnam | 29.5 | |

| Gulf War | 18.5 | |

| Peacetime | 19.2 | |

| PTSD Checklist, M (SD) | 65.3 (11.6) | |

| Mental Health Diagnoses in Medical Record (%) | ||

| PTSD diagnosis, yes | 92.7 | |

| Other anxiety disorder, yes | 23.2 | |

| Bipolar disorder, yes | 3.7 | |

| Depression, yes | 28.3 | |

| Psychotic disorder, yes | 0.4 | |

| Other mental health diagnosis, yes | 15.4 |

Procedures

Contact information was provided to hub site’s research staff for all veterans initiating a TFT for PTSD across participating VAs. Consistent with standard mailed survey methodology (Dillman et al., 2014), a pre-notification letter was sent, describing the study and who to contact to opt out of participation. A survey packet was mailed to each veteran, including a cover letter reviewing informed consent, a survey, a postage-paid return envelope, and a request to nominate a loved one for survey participation. Each non-respondent received three additional mailings: a postcard reminder, second survey with cover letter, and third survey with cover letter using overnight (UPS Express) mail. The study was funded by both the Department of Defense (DoD) and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). Due to local policies, participants in the VA-funded portion of the study (veteran n = 123; loved one n = 89) received payment after returning surveys (a $50 gift card), while participants for the DoD-funded portion received payment with initial survey mailings (a $20 cash incentive). Differences in incentives were consistent with recommendations for larger payments if delivered after (versus before) survey completion (Dillman et al., 2014). Mailing procedures for loved ones was identical to that for veterans. The study was conducted in compliance with the Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) at each of the participating VA healthcare facilities, the University of Minnesota’s IRB, and the United States Army Medical Research and Materiel Command’s Human Research Protections Office.

The response rate for veterans was 61% (59.6% among those who received a pre-incentive versus 67.2% of those receiving a post-incentive, p = .055). Many of the veteran participants nominated a loved one (67%), and 82.1% of those loved ones responded. Nearly 42% (41.8%) of the sample initiated PE and 58.2% initiated CPT. Some participants received CPT in a group format (16.2%). Fifty-one percent (50.9%) failed to successfully complete treatment. Dropout rates differed significantly by site (Site 1 = 43.4%, Site 2 = 50.6%; Site 3 = 52.6%; Site 4 = 63.0%, χ2 = 9.93, p = .02), but not by treatment type (CPT = 52.7%; PE = 48.3%, χ2 =0.94, p = .33) or modality (individual therapy = 52.3%; group = 43.9%, χ2 = 1.91, p = .17).

Materials

Support system factors

Veteran report of social control

Indices of social control are typically administered to the recipient of the control efforts and tailored to the behavioral target of interest for a given research study (Mead & Irish, 2016; Craddock et al., 2015). For the present study, content was drawn from a pool of items developed to measure how family members encourage individuals with PTSD to approach trauma-reminders (Fredman et al., 2014). In study surveys, each veteran was first asked to identify the person to which he/she was closest. Then two questions were presented about this loved one’s use of social control strategies: Has this person ever encouraged you to get in or stay in mental health treatment (yes/no)? Has this person ever encouraged you to face things that make you anxious or uncomfortable (yes/no)? Psychometric examination of these items indicated they are likely best examined as separate predictors (Meis et al., 2018).

Loved one report of symptom accommodation

An 8-item version of the Significant Others’ Responses to Trauma Scale (SORTS) assessed symptom accommodation (as reported by loved ones; Fredman et al., 2014). The SORTS has demonstrated factor validity and correlates with social support, individual distress, relationship distress, and patients’ depression and anger. (present sample, α = .94). The scale was shortened to reduce response burden and optimize response rates (Dillman et al., 2014). Items with the greatest item-total correlations from the original 14 item scale were retained. Example items include how often, did you help the veteran with a task because he/she was having trouble concentrating, did you make excuses to others for the veteran’s behavior or try to manage his/her relationships with other people, did you change your routines due to the veteran’s difficulties.

Veteran report of relationship strain

We used the interpersonal stressors scale from the Life Stressors and Social Resources Inventory (LISRES; Moos, Feen, & Billings, 1988). The interpersonal stressors subscale consists of five items that address the more stress-related aspects of a relationship (e.g., How often is he/she critical of you?). Consistent with a prior PTSD study (Laffaye, Cavella, Drescher, & Rosen, 2008), items were scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from Not at all (0) to Extremely (4; present sample, α = .80).

Veteran report of relationship type

As the influence of support network factors on TFT dropout may vary with who the veteran is closest to, participants were asked to identify “the person in your life that you are closest to who is over 18 years of age.” Response options included (a) significant other/romantic partner, (b) former significant other (ex-wife/husband, ex-fiancé, ex-boyfriend/girlfriend), (c) mother/father, (d) sister/brother, (e) son/daughter, (f) other family member, (g) friend (not related to me), (f) other. Responses were collapsed into intimate/partner (1) and family member/friend (0) to use as a covariate in analyses.

Veteran factors

All veteran factors were assessed through the veterans’ surveys. Veteran factors across three domains within Andersen’s (1995) behavioral model of health service use were selected. Domains include (1) need factors (PTSD symptom severity), (2) enabling factors (practical barriers to treatment, therapeutic alliance), and (3) health beliefs, which includes attitudinal variables about service use (attitudes about TFTs, perceived behavioral control over participation, stigma for seeking mental health treatment). Factors selected are consistent with those examined in prior research of dropout from CBT for anxiety disorders (i.e., motivation for treatment, expectancy for change, readiness for change, treatment credibility, therapeutic alliance, and practical barriers to participation; Taylor, Abramowitz, & McKay, 2012; Westra, Dozoios, & Marcus, 2007). Prior deployment to a Post-9/11 conflict was also added, given particularly poor utilization of mental health services found among those in this group (e.g., Hoge, Grossman, Auchterlonie, Riviere, Milliken, & Wilk, 2014; Mott, Mondragon, Hundt, Beason-Smith, Grady, & Teng, 2014; Sareen et al., 2007).

Attitudes about trauma-focused treatment

Veterans received a 6-item scale assessing patient attitudes about the value of participation in TFTs (6 items; Meis et al., 2018), consistent with the Attitude construct within the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB, Ajzen, 1991). The scale assesses expectations regarding the likely consequences of treatment participation (behavioral beliefs) and the value of those consequences (outcome evaluations), including treatment expectancies and treatment credibility. The scale has adequate factorial validity and correlates with behavioral intentions, TFT treatment dropout, therapeutic alliance, practical treatment barriers, and symptoms of PTSD (present sample, α = .88; Meis et al., 2018).

Perceived behavioral control over participation

We administered a 5-item scale assessing perceived behavioral control over TFT participation, consistent with the Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) construct within the TBP (Meis et al., 2018). The scale assesses the degree of control individuals believe they have over TFT participation, including the concepts of self-efficacy and readiness (Ajzen, 2002). The scale has adequate factorial validity and correlates with behavioral intentions, TFT treatment dropout, TFT homework compliance, disclosure of TFT participation, therapeutic alliance, and practical treatment barriers (present sample, α = .91).

Practical barriers to participation

A 7-item scale was adapted from prior research (Spoont et al., 2014) to assess the severity practical barriers facing the patient in getting adequate treatment, such as lack of transportation, familial responsibilities, or financial concerns. Response options ranged from Not at all (1) to Extremely (5), with scores indicating the extent to which each barrier is anticipated to interfere with treatment (present sample α = .77).

PTSD symptom severity

The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist, Specific Version (PCL-S) is a widely used 17-item measure of the severity of PTSD symptoms related to a specific traumatic event, based on the diagnostic criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders 4th Edition (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Weathers, Litz, Huska, & Keane, 1993). The PCL-S has strong internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and convergent validity with gold standard measures of PTSD (Ruggiero, Ben, Scotti, & Rabalais, 2008; Wilkins, Lang, & Norman, 2011; present sample, α = .91). To identify an event to respond to, participants were first asked their history of exposure to potentially traumatic events, using a checklist with a yes/no format. A write in option for events not captured by the list was provided. They then indicated which event continues to bother them the most. PCL-S instructions were adapted to ask respondents to complete the PCL-S based on this event.

Therapeutic alliance

The Session Rating Scale (SRS; Duncan, Miller, Sparks, Claud, Reynolds, Brown, & Johnson, 2003) is a 4-item scale assessing patients’ perspectives of therapeutic alliance across four domains: relationship, goals and topics, approach or method, and overall. Sufficient internal consistency (.88), test-retest reliability (.64; Duncan et al., 2003), and inter-item correlations (.74 to .86) have been found. Correlations with the Working Alliance Inventory range from, r = .49 to .63 (Campbell & Hemsley, 2009; present sample, α = .91).

Stigma for seeking mental health treatment

Stigma was measured using 3-items based on those used by Britt and colleagues (Britt, 2000; Britt et al., 2008). Items included, I worry others will think badly of me for getting mental health treatment, Getting mental health treatment makes me feel weak, and I am embarrassed to be getting mental health treatment. Items were assessed on a 5-point scale, ranging from Not at All to Extremely. (present sample, α = .89)

Post 9/11 veterans

Veterans were provided a checklist of conflicts and wars and asked in which they had participated. Participation in any Post 9/11 conflict/war was coded as a “1” and absence of participation was coded as a “0”. Post 9/11 conflicts included: Operation Enduring Freedom, Operation Iraqi Freedom, Operation New Dawn, War on Terror.

Dependent variable

Treatment dropout was coded via electronic medical records (dropout = 1; completion = 0). A participant was coded as a TFT dropout if his/her provider indicated that the patient had quit treatment prematurely or if there was no patient note stating that the final session of PE/CPT had been completed (Kehle-Forbes et al., 2015). Treatment dropout for every participant was coded by two different research staff. Any discrepancies between the two coders were resolved by the project coordinator or the Principal Investigator.

Analyses

Missing data

Scales were created through substituting an individual’s mean item response for missing items when less than 20% of the individual’s responses were missing (prorating). Missingness for any individual scale score was limited and ranged from 0.4% (PTSD symptom severity scores) to 7.4% (attitudes about trauma-focused treatment). Complete data was available for 223 of the 272 veteran-loved one dyads (82% of cases). Consequently, primary analyses were conducted using available case analysis. To examine the possibility that missingness led to biased study findings, we then repeated our analyses using Proc MI (SAS 9.2) to impute the monotone missingness in the predictors of interest. As dropout was obtained from hospital records, there were no missing values on the outcome.

Controlling for veteran-level variables

Given our sample size, the nesting of our data within four sites, and the number of veteran-level predictors assessed, entering the veteran-level predictors as individual variables would have eroded statistical power. We instead used a propensity modeling procedure to control for veteran-level predictors. First, the veteran-level variables were used as predictors in a logistic regression model, and a score was created for each participant indicating his/her predicted probability (propensity) for dropping out. These scores were then grouped into three propensity classes, and regression models were stratified by propensity class (Little & Rubin, 2002). The method used was based on a stratified likelihood where the logistic function links the model predictors (loved one variables) to dropout and develops ML estimators of model coefficients using the product of the three within-strata likelihoods.

Primary analyses

Main analyses were conducted using a series of logistic regressions predicting treatment dropout, stratified by propensity class. Models contained three covariates: relationship type, study site, and the number of sessions a veteran attended prior to completing his/her Time 1 survey. Our first regression model tested the unique effects of each of our support system factors in predicting treatment dropout. Our second model added interaction terms to test if the effects of support system factors on treatment dropout varied with relationship strain. Non-significant interactions (p > .10) were then trimmed from the model. Simulation studies demonstrate tests of interactions are typically underpowered (Aiken & West, 1991). Consequently, interaction terms with a p-value below .10 were probed in follow-up analyses.

Follow-up regression analyses evaluated relations between support system factors and treatment dropout at low, medium, and high levels of relationship strain. High and low values of relationship stress were calculated by adding or subtracting 1 standard deviation from the centered variable (Aiken & West, 1991). These models retained the same predictors and were also stratified by veteran-level propensity to dropout.

Results

Correlations among study predictors, moderators, and outcomes are provided in Table 2. Support system factors evinced small to moderate inter-correlations (rs = −.05 to .44), with the strongest association found between veteran reports on the two social control variables. Significantly greater likelihood of treatment dropout was found among those whose loved ones reported greater symptom accommodation. Significantly lower likelihood of dropout was found among veterans who reported social control efforts to approach distress.

Table 2.

Unadjusted Correlations Between Study Variables and Outcomes of Interest

| M/% | SD | n | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Symptom accommodation | 11.4 | 8.9 | 266 | -- | |||||||||||

| 2. Social control to seek MH treatment | 77.4% | NA | 266 | .09a | -- | ||||||||||

| 3. Social control to approach distress | 66.2% | NA | 266 | .12* | .44*** | -- | |||||||||

| 4. Relationship strain | 13.6 | 4.0 | 268 | −.26*** | −.09a | −.05 | -- | ||||||||

| 5. Attitudes about trauma-focused treatment | 33.1 | 11.5 | 252 | −.17** | .01 | .12* | .18** | -- | |||||||

| 6. Perceived control over participation | 24.5 | 5.1 | 261 | .14* | −.03 | .06 | .14* | .59*** | -- | ||||||

| 7. Practical barriers to participation | 12.3 | 5.1 | 261 | .18** | .04 | .01 | −.24*** | −.22** | −.24*** | -- | |||||

| 8. PTSD symptom severity | 65.3 | 11.6 | 271 | .27*** | .07 | −.04 | −.16* | −.26*** | .02 | .24*** | -- | ||||

| 9. Therapeutic alliance | 19.9 | 4.4 | 256 | −.13* | −.02 | .00 | .19** | .53*** | .46*** | −.21*** | −.08 | -- | |||

| 10. Stigma for seeking treatment | 7.3 | 3.8 | 260 | .18** | .01 | −.02 | −.29** | −.18** | −.05 | .30*** | .34*** | −.06 | -- | ||

| 11. Post 9/11 veterans | 46.5% | NA | 272 | .06 | .14* | .04 | −.08 | −.08 | −.08 | .20** | .02 | −.12* | −.02 | -- | |

| 12. Treatment Dropout | 44.9% | NA | 272 | .11* | .05 | −.12* | −.09 | −.17*** | −.21*** | .09b | .08b | −.10a | .01 | .13* | -- |

p < .05.

p < .01

p < .001

NA = Not applicable; MH = Mental health

p-value was approaching significance (p < .10)

Note. Correlations are appropriate to the scale of the variables (i.e., Pearson Product Moment for continuous scales/items, Spearman for continuous with categorical scales/items, or Kendall Tau for two categorical items/scales).

Primary analyses

When entered into the stratified logistic regression model, only social control to approach distress was uniquely associated with lower odds of treatment dropout (OR = 0.45; Table 3). This indicates that veterans who reported that a loved one encouraged them to approach things that made them anxious or uncomfortable were 2.22 times more likely to finish treatment, than veterans who did not report this encouragement. All other unique associations between support system factors and treatment dropout failed to achieve significance thresholds. Next, interaction terms were added to the model. The interaction between social control to attend treatment and relationship strain was non-significant (p > .10), so this term was dropped. Veterans’ reports of efforts at social control to approach distress continued to uniquely, significantly predicted a lower likelihood of treatment dropout. The interaction between social control to approach distress and relationship strain was approaching significance (p = .091).

Table 3.

Support System Factors and Treatment Dropout

| Complete Case (n = 231) | Imputed (n = 272) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reporter | b | SE | Wald | OR | p | b | SE | p | |

| Loved one symptom accommodation | LO | .03 | .02 | 2.59 | 1.03 | .107 | .02 | .02 | .208 |

| Social control to seek MH treatment | V | .26 | .20 | 1.66 | 1.70 | .197 | .28 | .19 | .140 |

| Social control to confront fears | V | −.40 | .17 | 5.26 | 0.45 | .022 | −.36 | .16 | .026 |

| Relationship Strain | V | −.03 | .04 | 0.53 | 0.97 | .467 | −.03 | .04 | .381 |

Note. V = Veteran; LO = Loved one. Model also included study site, relationship type, and sessions completed before returning surveys as covariates: Complete case analysis, site (bs = −.37 to .26; ps = .122 to .381), relationship type (b = −.16, p = .406), and sessions before returning surveys (b = −.27, p = .010). Imputed model, site (bs = −.29 to .02; ps = .188 to .950), relationship type (b = −.07, p = .710), and sessions completed before returning surveys (b = −.25, p = .007).

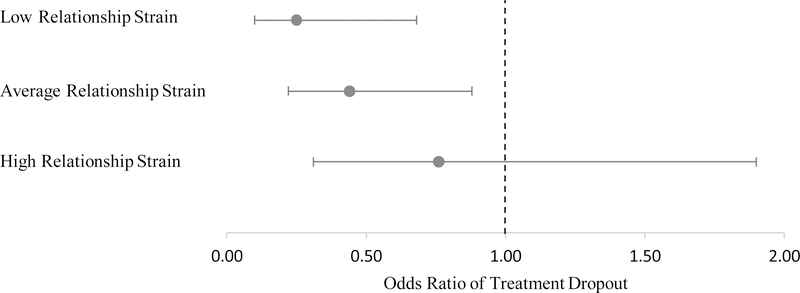

As the interaction term was approaching significance, we conducted three follow-up analyses (simple slopes analyses). For the first and second of these follow-up analyses, associations between social control to approach trauma-related distress and reduced odds of treatment dropout were statistically significant (low strain, OR = 0.25, 95% CI: 0.09, 0.68; moderate strain, OR = 0.44, 95% CI: 0.22, 0.88). Specifically, veterans reporting encouragement to confront distress in low-strain relationships were nearly 3.95 times more likely to complete treatment than those in low-strain relationships, who did not report this encouragement. When veterans in relationships with moderate strain reported encouragement, they were 2.27 times more likely to complete treatment, than when veterans in moderately-strained relationships denied such encouragement. For the third follow-up analysis, at high levels of relationship strain, the association between social control to approach distress and dropout was no longer statistically significant (OR = 0.76, 95% CI: 0.31, 1.90). See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Associations between Odds of Treatment Dropout and Social Control to Confront Distress, by Severity of Relationship Strain

Multiple imputation

When analyses were repeated using multiple imputation, the magnitude and direction of effects were comparable to the primary analyses. Effect estimates between complete case analysis and multiple imputation differed by b = .00 to .27 (see Tables 3 and 4). This suggests that item response bias was not driving our effects.

Table 4.

Support System Factors and Treatment Dropout with Relationship Strain as a Moderator

| Complete Case (n = 231) | Imputed (n = 272) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reporter | b | SE | Wald | p | b | SE | p | |

| Symptom accommodation | LO | .02 | .02 | 1.88 | .170 | .02 | .02 | .272 |

| Social control to seek MH treatment | V | .29 | .21 | 1.88 | .170 | .29 | .19 | .125 |

| Social control to confront fears | V | −1.34 | .59 | 5.16 | .023 | −1.07 | .55 | .050 |

| Relationship Strain | V | −.05 | .04 | 1.57 | .210 | −.05 | .04 | .212 |

| Relationship strain*Social control to confront | .07 | .04 | 2.86 | .091 | .05 | .04 | .167 | |

Note. LO = Loved one. V = Veteran. Additional covariates include study site, relationship type, and sessions completed before returning surveys: Complete case: site (bs = −.37 to .30; ps = .124 to .330), relationship type (b = −.15, p = .440), and sessions before returning surveys (b = −.29, p = .007). Imputed model: site (bs = −.29 to .04; ps = .191 to .895), relationship type (b = −.06, p = .729), and sessions before returning surveys (b = −.26, p = .006).

Discussion

The present study was designed to improve our understanding of how support systems may influence participation in TFTs for PTSD. We found that veterans who reported their closest loved ones had encouraged them to face things that made them anxious or uncomfortable were twice as likely to complete treatment compared to veterans reporting their loved ones had not given them this encouragement. Findings indicate that perceived encouragement to be courageous in the face of distress may serve as a powerful driver for veterans to stick with treatments that emphasize this approach to recovery. Veterans who reported their social environments do not directly encourage such behavior were at a comparative disadvantage when entering these treatments. Importantly, analyses controlled for to whom the veteran was closest (intimate partner versus family member or friend), and these associations were found even after considering individual-focused factors, such as veterans’ TFT attitudes, practical barriers to participation, PTSD symptom severity, and therapeutic alliance.

Veterans’ reports of encouragement by loved ones to get into or stay in mental health treatment did not significantly predict dropout from TFTs. This contrasts with a prior study demonstrating that family encouragement promotes treatment uptake (Spoont et al., 2014). Perhaps once an individual has initiated treatment, particularly a TFT, encouragement by an important loved one to face distress is more important than general encouragement to get in or stay in psychotherapy. Accommodation, as reported by loved ones, was significantly correlated with treatment dropout. However, these associations were nonsignificant in multivariate models, suggesting accommodation associations do not persist once other support system factors and individual-level predictors are considered.

The interaction effect was approaching significance, indicating that the association between treatment dropout and perceived encouragement to face distress varied with relationship strain (p = .091). As interaction effects are typically underpowered (Aiken & West, 1991), we examined this effect further in three subsequent regression analyses. These analyses suggested that the strongest links between social control and greater treatment retention were for those in the most well-adjusted relationships with their loved ones. While conclusions cannot be made based on these analyses, this highlights an important area for future research.

Our findings have important implications for practice. Clinicians should consider routinely assessing to what degree veterans entering TFTs have encouragement by a closest loved one to participate in activities that may be distressing. This loved one could be an intimate partner, but it could just as importantly be a buddy, a parent, or another family member. While more work is needed, outreach to loved ones that provides (a) a compelling case that confronting distress is essential for PTSD recovery and (b) simple instruction to encourage veterans to confront distress, may be sufficient to bolster adherence. This could involve appraising what kinds of supportive behaviors have worked for the dyad in the past and asking loved ones to emphasize and track these behaviors (Beach, Fincham, & Katz, 1998). Clinicians can underscore the importance of non-critical validation and basic listening when encouraging veterans to approach distress, as these skills are likely uniformly beneficial (Beach et al., 1998). Recommendations are consistent with those from other family-based treatments for mental health conditions (e.g., Miller, Meyers, & Tonigan, 1999; Monson & Fredman, 2012; O’Farrell & Fals-Stewart, 2006).

Strengths and Limitations

Our study design possessed several strengths. We examined TFT dropout in a prospective design among a large, clinical population of veterans initiating TFT across several VA hospitals. We included reports from both veterans and their loved ones. We tested our hypotheses among veterans naturally receiving TFTs in real world care. We also controlled for veteran-level predictors of treatment dropout. At the same time, our indices of social control were reliant on two, dichotomous items, that were developed for the survey. These items are not the only ways social control could influence TFT retention. Additionally, these items evaluate naturally occurring behavior that we would not expect loved ones to know could benefit treatment adherence (i.e., encouraging veterans to confront their distress). The mailed survey format prevented us from asking the veteran about how a family member may encourage or discourage approaching activities, thoughts, and feelings specific to the veteran’s personal trauma history. This could have attenuated associations between dropout and either social control or accommodation. Future research is needed using a broader range of social control items and alternative methodology (e.g., interviews, dyadic behavioral observation, laboratory research) that could personalize assessments the individual’s trauma history. While response rates were within appropriate limits, findings are limited to those respondents willing to return surveys and veterans willing to nominate loved ones for survey participation. We also do not know how findings would generalize beyond CPT and PE to other treatments for PTSD. Lastly, the sample is largely comprised of men and of limited variability in racial/ethnic subgroups.

While not necessarily a limitation of the study, rates of dropout from TFT in our sample are worth comment (51%). These rates are higher than those seen in many prior published VA samples (e.g., Chard et al., 2010; Kehle-Forbes et al, 2016; Schnurr et al., 2007; Surís et al., 2013; Thorp et al., 2012). Rates of dropout did not vary significantly by treatment type (PE vs CPT) or modality (group vs individual), but did vary by site, ranging from 43% to 63%. While these rates are high, they are within the range of dropout rates reported in the literature. Additionally, many published samples relied on unique populations, such as providers learning PE/CPT with extra monitoring and supervision, from a single VA hospital with a robust research program, or from randomized controlled trials. A prior meta-analysis of psychotherapy for Post-9/11 combat veterans found significant greater dropout rates among those receiving treatment in routine clinical care versus within an RCT (42% versus 28%; Goetter, Bui, Ojserkis, Zakarian, Weintraub Brendel, & Simon, 2015).

In summary, even after accounting for individual-level predictors of dropout, such as veteran attitudes, therapeutic alliance, and symptom severity, when veterans reported a loved one encouraged them to confront their distress, their odds of completing treatment doubled. Our data also signal that, when examining links between social control efforts and treatment retention, relationship strain may be an important consideration. Further work is needed to deepen our understanding of how social control influences psychotherapy retention and develop interventions that optimize social control efforts to help veterans complete TFTs.

Public Health Significance.

Support system factors are especially important to understanding dropout from trauma-focused treatment for PTSD. Specifically, veterans who reported their loved ones encouraged them to face distress were twice as likely to remain in PTSD treatment than veterans who denied such encouragement. Findings persist even after accounting for traditional, individual-level risk factors predicting dropout. Outreach to loved ones to increase their likelihood of encouraging veterans to face their distress may be a viable path for improving retention in trauma-focused treatments for PTSD.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the Department of Defense’s Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program (W81XWH-12–1-0619) and the Department of Veterans Affairs (HSR&D CDA 10–035; RRP 12–229). This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Center for Care Delivery & Outcomes Research and the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Health Care System. The findings and conclusions in this document are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government. No investigators have affiliations or financial involvement that conflict with material presented.

The authors would like to thank the HomeFront team for their work in support of this project, especially Dr. Karen A. Kattar, Kimberly Stewart, Rebecca Swain, Martina Radic, Kimberly Henriksen, Dr. Talee Vang, Lee Kravetz, Tegan Carr, Christopher Hoge, and numerous research assistants who have volunteered on the HomeFront team. We would also like to thank Dr. Steffany Fredman for her generous feedback.

References

- Aiken LS, & West SG (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I (2002). Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned Behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition, Text Revision; DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen RM (1995). Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36, 1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach RHS, Fincham FD, & Katz J (1998). Marital therapy in the treatment of depression: Toward a third generation of therapy and research. Clinical Psychology Review, 18, 635–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brehm JW (1966). A theory of psychological reactance. Oxford, England: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Britt TW (2000). The stigma of psychological problems in a work environment: Evidence from the screening of servicemembers returning from Bosnia. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30, 1599–1618. [Google Scholar]

- Britt TW, Greene-Shortridge TM, Brink S, Nguyen QB, Rath J, Cox AL, … & Castro C (2008). Perceived stigma and barriers to care for psychological treatment: Implications for reactions to stressors in different contexts. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 27, 317–335. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A & Hemsley S (2009). Outcome Rating Scale and Session Rating Scale in psychological practice: Clinical utility of ultra-brief measures. Clinical Psychologist, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Chard KM, Schumm JA, Owens GP, & Cottingham SM (2010). A comparison of OEF and OIF veterans and Vietnam veterans receiving cognitive processing therapy. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23, 25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craddock E, van Dellen MR, Novak SA, & Ranby KW (2015). Influence in relationships: A meta-analysis on health-related social control. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 37, 118–130. doi: 10.1080/01973533.2015.1011271 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Cohen B, & Igram S (1990). Contextual determinants of the perceived supportiveness of helping behaviors. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7, 553–562. [Google Scholar]

- Dillman DA, Smyth JD, & Christian LM (2014). Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. 4 ed. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan BL, Miller SD, Sparks J, Claud DA, Reynolds LR, Brown J, & Johnson LD (2003). The session rating scale: Preliminary psychometric properties of a “working” alliance measure. Journal of Brief Therapy, 3, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Eftekhari A, Ruzek JI, Crowley JJ, Rosen CS, Greenbaum MA, & Karlin BE (2013). Effectiveness of national implementation of Prolonged Exposure therapy in Veterans Affairs care. JAMA Psychiatry, 70, 949–55. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans L, Cowlishaw S, & Hopwood M (2009). Family functioning predicts outcomes for veterans in treatment for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Family Psychology, 23, 531–539. doi: 10.1037/a0015877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekete EM, Stephens MAP, Druley JA, & Greene KA (2006). Effects of spousal control and support on older adults’ recovery from knee surgery. Journal of Family Psychology, 20, 302–310. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez E, Salem D, Swift JK, & Ramtahal N (2015). Meta-analysis of dropout from cognitive behavioral therapy: Magnitude, timing, and moderators. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83, 1108–1122. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks MM, Stephens MAP, Rook KS, Franklin BA, Keteyian SJ, & Artinian NT (2006). Spouses’ provision of health-related support and control to patients participating in cardiac rehabilitation. Journal of Family Psychology, 20, 311–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredman SJ, Pukay-Martin ND, Macdonald A, Wagner AC, Vorstenbosch V, & Monson CM (2016). Partner accommodation moderates treatment outcomes for couple therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84, 79–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredman SJ, Vorstenbosch V, Wagner AC, Macdonald A, & Monson CM (2014). Partner accommodation in posttraumatic stress disorder: Initial testing of the Significant Others Responses to Trauma Scale (SORTS). Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28, 372–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetter EM, Bui E, Ojserkis RA, Zakarian RJ, Weintraub Brendel R, & Simon NM (2015). A systematic review of dropout From psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder among Iraq and Afghanistan combat veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28, 401–409. doi: 10.1002/jts.22038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson VS, Mascatelli K Seltman H, Korytkowski M, & Hausmann LRM (2016). Implications of supportive and unsupportive behavior for couples with newly diagnosed diabetes. Health Psychology, 35, 1047–1058. doi: 10.1037/hea0000388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson VS, Novak SA, Lepore SJ, & Eton DT (2004). Spouse social control efforts: Relations to health behavior and well-being among men with prostate cancer. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 21, 53–68. doi: 10.1177/0265407504039840. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hembree EA, Foa EB, Dorfan NM, Street GP, Kowalski J, & Tu X (2003). Do patients dropout prematurely from exposure therapy for PTSD? Journal of Traumatic Stress, 16, 555–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge CW, Grossman SH, Auchterlonie JL, Riviere LA, Milliken CS, & Wilk JE (2014). PTSD treatment for soldiers after combat deployment: Low utilization of mental health care and reasons for dropout. Psychiatric Services, 5, 997–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imel ZE, Laska K, Jakupcak M, & Simpson TL (2013). Meta-analysis of dropout in treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81, 394–404. doi: 10.1037/a0031474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (2007). Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: An assessment of the evidence. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Karlin BE, Ruzek JI, Chard KM, Eftekhari A, Monson CM, Hembree EA, … & Foa EB (2010). Dissemination of evidence-based psychological treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder in the Veterans Health Administration. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23, 663–673. 10.1002/jts.20588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehle-Forbes SM, Meis LA, Spoont MR, & Polusny MA (2016). Treatment initiation and dropout from Prolonged Exposure and Cognitive Processing Therapy in a VA outpatient clinic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 8, 107–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoll N, Burkert S, Scholz U, Roigas J, & Gralla O (2012). The dual-effects model of social control revisited: Relationship satisfaction as a moderator. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 25, 291–307. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2011.584188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laffaye C, Cavella S, Drescher K, & Rosen C (2008). Relationships among PTSD symptoms, social support, and support source in Veterans with chronic PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21, 394–401. doi: 10.1002/jts.20348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, & Butterfield RM (2005). Antecedents and reactions to health-related social control. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 416–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, & Rook KS (1999). Social control in personal relationships: Impact on health behaviors and psychological distress. Health Psychology, 18, 63–71. 10.1037/0278-6133.18.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, & Rubin DB (2002). Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. Hoboken, N.J: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Management of Post-Traumatic Stress Working Group. (2017). VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Post-Traumatic Stress and Acute Stress Disorder. Washington (DC): Veterans Health Administration, Department of Defense. [Google Scholar]

- Meis LA, Erickson EPG, Hagel Campbell EM, Noorbaloochi S, Velasquez TL, Leverty DM, Thompson K, & Erbes C (2018). A Theory of Planned Behavior scale for adherence to trauma focused PTSD treatments. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mead MP, & Irish LA (2016). Spousal influence on CPAP adherence: Applications of health-related social control. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 10/8, 443–454, 10.1111/spc3.12260 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meis LA, Barry RA, Erbes CR, Kehle SM, & Polusny MA (2010). Relationship adjustment, PTSD symptoms, and treatment utilization among coupled National Guard soldiers deployed to Iraq. Journal of Family Psychology, 24, 560–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Meyers RJ, & Tonigan JS (1999). Engaging the unmotivated in treatment for alcohol problems: A comparison of three strategies for intervention through family members. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67, 688–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monson CM, & Fredman SF (2012). Cognitive-Behavioral Conjoint Therapy for PTSD: Harnessing the healing power of relationships. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Monson CM, Taft CT, & Fredman SJ (2009). Military-related PTSD and intimate relationships: From description to theory-driven research and intervention development. Clinical Psychology Review, 29, 707–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Fenn CB, & Billings AG (1988). Life stressors and social resources: An integrated assessment approach. Social Science & Medicine, 27, 999–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott JM, Mondragon S, Hundt NE, Beason-Smith M, Grady RH, & Teng EJ (2014). Characteristics of U.S. veterans who begin and complete prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy for PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27, 265–273. doi: 10.1002/jts.21927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrell TJ, & Fals-Stewart W (2006). Behavioral couples therapy for alcoholism and drug abuse. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pekarik G (1985). Coping with dropouts. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 16, 114–123. [Google Scholar]

- Pukay-Martin ND, Torbit L, Landy MSH, Wanklyn SG, Shnaider P, Lane JEM, & Monson CM (2015). An uncontrolled trial of a present-focused cognitive-behavioral conjoint therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 71, 302–312. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rook KS, Thuras PD, & Lewis MA (1990). Social control, health risk taking, and psychological distress among the elderly. Psychology and Aging, 5, 327–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotunda RJ, & Doman K (2001). Partner enabling of substance use disorders: Critical review and future directions. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 29, 257–270. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero K, Ben K, Scotti J, & Rabalais A (2003). Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 16, 495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, Stein MB, Belik SL, Meadows G, & Asmundson GJ (2007). Combat and peacekeeping operations in relation to prevalence of mental disorders and perceived need for mental health care: findings from a large representative sample of military personnel. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64, 843–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayer NA, Friedman-Sanchez G, Spoont M, Murdoch M, Parker L, Chiros C, & Rosenheck R (2009). A qualitative study of determinants of PTSD treatment initiation in Veterans. Psychiatry, 72, 238–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr PP, Friedman MJ, Engel CC, Foa EB, Shea MT, Chow BK, … & Bernardy N (2007). Cognitive behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in women: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 297, 820–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiner B, D’Avolio LW, Nguyen TM, Zayed MH, Young-Xu Y, Desai RA, … & Watts BV (2013). Measuring use of evidence based psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 40, 311–318. doi: 10.1007/s10488-012-0421-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoont MR, Nelson DB, Murdoch M, Rector T, Sayer NA, Nugent S, & Westermeyer J (2014). Impact of treatment beliefs and social network encouragement on initiation of care by VA service users with PTSD. Psychiatric Services, 65, 654–662. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens MAP, Fekete EM, Franks MM, Rook KS, Druley JA, & Greene K (2009). Spouses’ use of pressure and persuasion to promote osteoarthritis patients’ medical adherence after orthopedic surgery. Health Psychology, 28, 48–55. doi: 10.1037/a0012385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surís AM, Link-Malcom J, Chard K, Ahn C, & North C (2013). A randomized clinical trial of cognitive processing therapy for veterans with PTSD related to military sexual trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26, 28–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarrier N, Sommerfield C, & Pilgrim H (1999). Relatives’ expressed emotion (EE) and PTSD treatment outcome. Psychological Medicine, 29, 801–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S Abramowitz JS, & McKay D (2012). Non-adherence and non-response in the treatment of anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26, 583–589. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson-Hollands J, Abramovitz R, Tompson MC, & Barlow DH (2015) A randomized controlled trial of a brief family intervention to reduce accomodation in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A preliminary study. Behavior Therapy, 46, 218–229. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson-Hollands J, Edson A, Tompson MC, & Comer JC (2014). Family involvement in the psychological treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology, 28, 287–298. doi: 10.1037/a0036709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorp SR, Stein MB, Jeste DV, Patterson TL, & Wetherell JL (2012). Prolonged exposure therapy for older veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: A pilot study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 20, 276–280. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3182435ee9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS (2002). Health-related social control within older adults’ relationships. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 57, 387–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, & Anders SL (2001). Social control of health behaviors in marriage. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31, 467–485. [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D (1987). Family status and health behaviors: Social control as a dimension of social integration. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 28, 306–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D (1992). Gender, marital status and the social control of health behavior. Social Sciences & Medicine, 14, 907–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F, Litz B, Herman D, Huska J, & Keane T (1993). The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, Validity, and Diagnostic Utility. Paper presented at the Annual Convention of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, San Antonio, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Westmaas JL, Wild TC, & Ferrence R (2002). Effects of gender in social control of smoking cessation. Health Psychology, 21, 368–376. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.4.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westra HA, Dozoios DJA, & Marcus M (2007). Expectancy, homework compliance, and initial change in cognitive–behavioral therapy for anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75, 363–373. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.3.363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierzbicki M, & Pekarik G (1993). A meta-analysis of psychotherapy dropout. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 24, 190–195. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.24.2.190 [DOI] [Google Scholar]