Abstract

Objectives

We examined the effects of magnanimous therapy on psychological coping, adjustment, living function, and survival rate in patients with advanced lung cancer.

Methods

Patients with advanced lung cancer (n = 145) matched by demographics and medical variables were randomly assigned to an individual computer magnanimous therapy group (ic-mt), a group computer magnanimous therapy group (gc-mt), or a control group (ctrl). Over 2 weeks, the ic-mt and gc-mt groups received eight 40-minute sessions of ic-mt or gc-mt respectively, plus usual care; the ctrl group received only usual care. The Cancer Coping Modes Questionnaire (ccmq), the Psychological Adjustment Scale for Cancer Patients (pascp), and the Functional Living Index–Cancer (flic) were assessed at baseline and 2 weeks later. The relationships of changes in those indicators were analyzed, and survival rates were compared.

Results

The psychological coping style, adjustment, and living function of the ic-mt and gc-mt groups improved significantly after the intervention (p < 0.01). After 2 weeks, significant (p < 0.01) differences between the treatment groups and the ctrl group in coping style, adjustment, and living function suggested successful therapy. The changes in living function were correlated with changes in psychological coping and adjustment. No difference in efficacy between ic-mt and gc-mt was observed. The survival rate was 31.84% in the ic-mt group and 9.375% in the ctrl group at 2 years after the intervention.

Conclusions

In patients with advanced lung cancer, ic-mt and gc-mt were associated with positive short-term effects on psychological coping style, adjustment, and living function, although the magnitude of the effect did not differ significantly between the intervention approaches. The effects on living function are partly mediated by improvements in psychological coping and adjustment.

Keywords: Magnanimous therapy; lung cancer, advanced; coping style; adjustment; living function; therapy effects

INTRODUCTION

People with advanced lung cancer often experience significant psychological distress1–3. These patients have a heavy burden of physical symptoms, poor prognosis, and high mortality, and compared with patients having other types of cancer, they experience increased rates of psychological distress4–7. The psychological distress of patients with lung cancer has been found to persist throughout the clinical course of the illness8. Unmet psychological needs have been found to be significantly greater in those patients than in patients with other cancers9.

Psychosocial interventions have been developed to ameliorate distress in cancer patients, and systematic reviews and meta-analyses confirm that such interventions improve depression, anxiety, fatigue, pain, coping, adjustment, functional ability, and quality of life10–18. Cognitive behavioural therapy, education or information provision, relaxation, self-care strategies, unstructured therapies, and group social support have been found to be effective interventions10–18. Reasonable evidence from systematic reviews supports the particular effectiveness, in the short term, of cognitive behavioural therapy (in group or individual format)10–12,16.

Magnanimous therapy was originally created for cancer patients, based mainly on the psychological characteristics of long-term cancer survivors with good quality of life19. Those important characteristics included being or becoming magnanimous and open-minded, having a good mental health status and lower cancer or tumour-prone psychological level, and being able to cope with illness positively and magnanimously20–24. Magnanimous therapy focuses on enhancing a client’s insights and understanding of life, with the aim of restructuring their cognitive habits and modifying their behaviours to achieve a magnanimous and open-minded, enterprising and optimistic, harmonious, peaceful and relaxed state spiritually, psychologically, and physically, and then applying those traits in their problem-solving and daily life, until their life become a harmonious whole. This new psychotherapy for modifying a client’s cognition and behaviour is similar to cognitive behavioural therapy. The central theory of magnanimous psychotherapy holds that

■ negative feelings originate from not being magnanimous.

■ people can turn their habitual psycho-behavioural mode into an adjusted mode (a psycho-behavioral mode after adjustments).

■ human cognition, unconscious, and behaviour can be modified, and individuals can acquire a magnanimous state.

The technique of magnanimous therapy is to deliver effective and vivid information to create insight, understanding, and adjustments that help clients to attain a magnanimous state. The methods of insight, understanding, and adjustment include

■ establishing the belief that all problems can be solved.

■ stretching the breadth and angles of cognitive appraisal and learning that everything in the world is dialectical, multidimensional, changing, and dynamic.

■ fostering an ability to achieve psychological balance.

■ understanding cause and effect, and properly analyzing causality in reality.

■ maintaining peace of mind and a normal heart, and becoming used to “taking things easy.”

■ being natural, simple, and spontaneous.

■ being grateful.

The process of magnanimous therapy includes

■ assessing the client’s status.

■ selecting the type of magnanimous therapy.

■ establishing the goals of therapy.

■ presenting little stories, cases, and so on, to enlighten and inspire insight, understanding, and adjustment in the client.

■ making the client understand and reach insight into their life.

■ having the client repeat and review their learnings and understanding.

■ having the client apply all the ways of being magnanimous in daily life.

Magnanimous therapy is simple to conduct and easy to access (therapy tools are available), takes diverse forms (individual or group therapy, operational or computerbased therapy, story and game versions, regular or shortterm therapy, professional therapy or self-therapy), and is attractive (uses attractive little philosophical stories and cases as its therapy medium, games in which patients can decide the progress and ending of the each story, and interesting audiovisual therapy tools).

Our previous studies have shown that individual and group magnanimous therapy using stories presented by computer both could improve symptoms of anxiety and depression, psychological coping, adjusting effects, and quality of life for patients with breast cancer, with depression, and with hypertension25–29.

The aim of the present study was to assess the effects of individual computer magnanimous therapy (ic-mt) and group computer magnanimous therapy (gc-mt) on psychological coping, adjustment, and quality and length of life in patients with advanced lung cancer; to compare the effects achieved with those two types of computer magnanimous therapy (cmt); and to probe the possible mechanisms.

To our knowledge, this study is the first of its kind to explore the application and evaluation of cmt in patients with lung cancer.

METHODS

Study Design

The study was approved by the ethics committees of Guangdong Pharmaceutical University for Clinical Medicine (no. [2013] Clinical Medicine [06]). The study was a matched case–control tracking study of the effects of ic-mt and gc-mt on psychological coping, adjustment, and quality and length of life in patients with lung cancer. Patients with advanced lung cancer matched by demographics, diagnosis, and types of oncotherapy were randomly assigned to either the ic-mt group, the gc-mt group, or the control (ctrl) group. The ic-mt and gc-mt groups received eight 40-minute sessions of cmt over 2 weeks in addition to oncotherapy and usual care; the ctrl group received only oncotherapy and usual care. Patients were assessed at baseline and 2 weeks later using the Cancer Coping Modes Questionnaire (ccmq)30, the Psychological Adjustment Scale for Cancer Patients (pascp)31, and the Functional Living Index–Cancer (flic)32–34. At 12 and 24 months after the intervention, individual telephone interviews were conducted to investigate the global psychological and somatic status and length of life of patients in the study groups. The differences in the efficacy of ic-mt and gc-mt were analyzed. The relationships between the measured variables were analyzed to probe possible mechanisms: if the variables showed any change, the relationships between changes in the flic, the pascp, and the ccmq were analyzed.

Patients

Patients were recruited from the oncology inpatient department of two teaching hospitals in Guangzhou during the period from September 2014 to August 2017. The inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of advanced lung cancer (stage III or IV, with pathology confirmation); age between 18 and 80 years; ability to complete a questionnaire and to receive psychotherapy; awareness of the cancer diagnosis; no apparent serious intellectual impairment or mental disease; score of 8 or more on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (a 14-item self-rating scale that measures anxiety and depression, and is designed specifically for patients with physical illnesses, and on which a score of ≥11 indicates “probable” psychological morbidity and a score of 8–10 indicates “possible” psychological morbidity); and signed written informed consent to participate the study. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy or lactation; current psychosis or history of a psychotic disorder; substance dependence (other than nicotine); other severe acute or unstable medical illness; or impaired cognition (determined as a score of <27 on the Mini-Mental State Examination, a 30-item questionnaire that is used extensively in clinical and research settings to measure cognitive impairment35,36). Patients were considered to have dropped out if they were absent from therapy for 2 or more of the sessions, or if their medical condition had deteriorated.

The Intervention

Participants allocated to the ic-mt and gc-mt groups received eight 40-minute sessions of cmt (4 sessions per week for 2 weeks). (The duration of hospitalization for lung cancer patients in China is usually 2 weeks.) Treatment was conducted by 1 of 2 trained research students using the cmt software. For the patients, each session consisted of an assessment before the intervention, the intervention (watching a therapy video and receiving interpretations of the video from the therapist), the assessment after the therapy, and a review on the part of the patient of what had been learned from the therapy, and as homework, how that learning could be applied for problem-solving and daily life. At the beginning of next session, the therapist would ask patients what they had achieved from the treatment and their personal inspirations. Each set of cmt videos consists of 8 short philosophical stories, accompanied by appropriate inspirations and enlightenments that help patients to achieve a magnanimous, enterprising, optimistic, relaxing, harmonious, and peaceful state. In the ic-mt group, the therapist used the video to treat one patient at a time and focused on individual traits and problems. In the gc-mt group, the video focused on inspiring a positive interaction effect in a group of participants facilitated by the therapist.

Outcome Measurements

Psychological coping modes were assessed using the 26-item ccmq self-rating scale developed in a previous study30. The ccmq explores 5 coping dimensions, including confrontation, avoidance and suppression, resignation, fantasy, and catharsis. Participants rate items on a 4-point scale (1, never; 4, always), with higher scores indicating adoption of the corresponding coping mode. The questionnaire has good reliability, with an alpha of 0.88.

Psychological adjustment was measured using the 36-item self-rated pascp31, a scale for cancer patients that explores 5 dimensions (effects on emotion or self-esteem, self-perception, daily life, relationships with others and social life, others) and general psychological adjustment. Participants rate items on a 5-point scale (1, very serious; 5, not at all), with higher scores indicating better adjustment. The scale has good reliability, with an alpha of 0.89.

Living function was examined using the flic, a 22-item self-administered questionnaire that was developed to determine the response of cancer patients to their illness and treatment32. The questionnaire uses a visual analog scale for each of 5 categories, including physical well-being and ability, emotional state, sociability, nausea, and hardship attributable to cancer. Each interval is divided in half, and responses are scored to the nearest whole integer. For certain items, the scale has been reversed so that a high score consistently represents higher quality of life. The flic is a reliable and valid instrument in Chinese cancer patients33,34. Alpha coefficients for the internal consistency of factor scores range from 0.64 to 0.87.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were performed in the IBM SPSS Statistics software application (version 19.0: IBM, Armonk, NY, U.S.A.). Quantitative data are described as means with standard deviation, and categorical data, as absolute frequencies and percentages. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were assessed using the chi-square test and analysis of variance to determine comparability between the groups. All analyses were two-sided, and p < 0.05 was considered significant.

The outcome variables at the baseline and 2-week assessments for the two groups were compared by t-test. Differences and changes from baseline in the outcome variables between the study groups were compared by one-way analysis of variance and Tukey honest significant difference. Pearson correlation was used to probe the impact of changes in functioning.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Groups

Table I presents the characteristics of the participants. No significant differences in baseline demographics between the groups were evident. Similarly, for same-stage cancer patients, no differences in medical variables were evident. At baseline, no statistically significant differences were observed between the ic-mt, gc-mt, and ctrl groups for all scores on the ccmq, pascp, and flic.

TABLE I.

Baseline characteristics of the study participants

| Characteristic | Magnanimous therapy group | Control group | F/χ2 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Individual computer | Group computer | ||||

| Participants (n) | 50 | 45 | 50 | ||

|

| |||||

| Mean age (years) | 59.78±9.94 | 57.69±11.16 | 60.90±11.07 | 1.09 | 0.34 |

|

| |||||

| Sex [n (%) men] | 31 (62) | 31 (69) | 30 (60) | 0.43 | 0.65 |

|

| |||||

| Marital status [n (%)] | 0.17 | 0.84 | |||

| Married | 45 (90) | 39 (87) | 45 (90) | ||

| Separated or widowed | 5 (10) | 6 (13) | 5 (10) | ||

|

| |||||

| Education [n (%)] | |||||

| Primary school | 13 (26) | 10 (22) | 12 (24) | 0.15 | 0.86 |

| Secondary school | 18 (36) | 18 (40) | 11 (22) | ||

| High school or technical school | 14 (28) | 12 (27) | 26 (52) | ||

| University degree or higher | 5 (10) | 5 (11) | 1 (2) | ||

|

| |||||

| Occupation [n (%)] | |||||

| Peasant | 13 (26) | 15 (33) | 12 (24) | 0.83 | 0.44 |

| Worker | 15 (30) | 14 (32) | 13 (26) | ||

| Staff | 6 (12) | 7 (16) | 12 (24) | ||

| Self-employed | 7 (14) | 3 (6) | 5 (10) | ||

| Other | 9 (18) | 6 (13) | 8 (16) | ||

|

| |||||

| Pathologic diagnosis [n (%)] | |||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 12 (24) | 9 (20) | 12 (24) | 1.92 | 0.15 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 30 (60) | 22 (49) | 26 (52) | ||

| Adenosquamous carcinoma | 4 (8) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | ||

| Small-cell carcinoma | 4 (8) | 13 (29) | 11 (22) | ||

|

| |||||

| Stage [n (%)] | |||||

| III | 16 (32) | 16 (36) | 19 (38) | 0.20 | 0.82 |

| IV | 34 (68) | 29 (64) | 31 (62) | ||

|

| |||||

| Type of treatment [n (%)] | 1.32 | 0.27 | |||

| Chemotherapy | 18 (36) | 27 (60) | 25 (50) | ||

| Radiotherapy | 15 (30) | 4 (9) | 12 (24) | ||

| Combined therapy | 17 (34) | 14 (31) | 13 (26) | ||

Changes in Psychological Coping Modes, Psychological Adjustment, and Living Functions

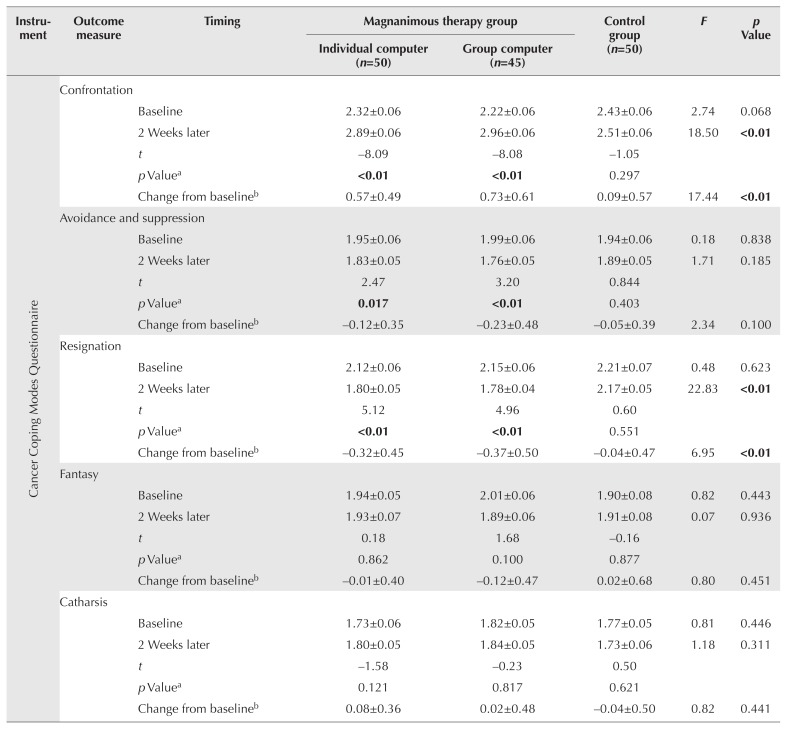

Table II shows the results of the analyses of the psychological measures.

TABLE II.

Measured outcomes (mean and standard error) in the participant groups

| Instrument | Outcome measure | Timing | Magnanimous therapy group | Control group (n=50) | F | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Individual computer (n=50) | Group computer (n=45) | ||||||

| Cancer Coping Modes Questionnaire | Confrontation | ||||||

| Baseline | 2.32±0.06 | 2.22±0.06 | 2.43±0.06 | 2.74 | 0.068 | ||

| 2 Weeks later | 2.89±0.06 | 2.96±0.06 | 2.51±0.06 | 18.50 | <0.01 | ||

| t | −8.09 | −8.08 | −1.05 | ||||

| p Valuea | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.297 | ||||

| Change from baselineb | 0.57±0.49 | 0.73±0.61 | 0.09±0.57 | 17.44 | <0.01 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Avoidance and suppression | |||||||

| Baseline | 1.95±0.06 | 1.99±0.06 | 1.94±0.06 | 0.18 | 0.838 | ||

| 2 Weeks later | 1.83±0.05 | 1.76±0.05 | 1.89±0.05 | 1.71 | 0.185 | ||

| t | 2.47 | 3.20 | 0.844 | ||||

| p Valuea | 0.017 | <0.01 | 0.403 | ||||

| Change from baselineb | −0.12±0.35 | −0.23±0.48 | −0.05±0.39 | 2.34 | 0.100 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Resignation | |||||||

| Baseline | 2.12±0.06 | 2.15±0.06 | 2.21±0.07 | 0.48 | 0.623 | ||

| 2 Weeks later | 1.80±0.05 | 1.78±0.04 | 2.17±0.05 | 22.83 | <0.01 | ||

| t | 5.12 | 4.96 | 0.60 | ||||

| p Valuea | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.551 | ||||

| Change from baselineb | −0.32±0.45 | −0.37±0.50 | −0.04±0.47 | 6.95 | <0.01 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Fantasy | |||||||

| Baseline | 1.94±0.05 | 2.01±0.06 | 1.90±0.08 | 0.82 | 0.443 | ||

| 2 Weeks later | 1.93±0.07 | 1.89±0.06 | 1.91±0.08 | 0.07 | 0.936 | ||

| t | 0.18 | 1.68 | −0.16 | ||||

| p Valuea | 0.862 | 0.100 | 0.877 | ||||

| Change from baselineb | −0.01±0.40 | −0.12±0.47 | 0.02±0.68 | 0.80 | 0.451 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Catharsis | |||||||

| Baseline | 1.73±0.06 | 1.82±0.05 | 1.77±0.05 | 0.81 | 0.446 | ||

| 2 Weeks later | 1.80±0.05 | 1.84±0.05 | 1.73±0.06 | 1.18 | 0.311 | ||

| t | −1.58 | −0.23 | 0.50 | ||||

| p Valuea | 0.121 | 0.817 | 0.621 | ||||

| Change from baselineb | 0.08±0.36 | 0.02±0.48 | −0.04±0.50 | 0.82 | 0.441 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Psychological Adjustment Scale for Cancer Patients | Impact on emotion or self-esteem | ||||||

| Baseline | 3.48±0.07 | 3.40±0.06 | 3.49±0.07 | 0.514 | 0.599 | ||

| 2 Weeks later | 3.64±0.06 | 3.66±0.06 | 3.50±0.05 | 2.50 | 0.86 | ||

| t | −2.16 | −3.01 | −0.06 | ||||

| p Valuea | 0.036 | <0.01 | 0.956 | ||||

| Change from baselineb | 0.15±0.51 | 0.26±0.57 | 0.00±0.51 | 2.76 | 0.067 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Self-perception | |||||||

| Baseline | 3.41±0.06 | 3.32±0.05 | 3.25±0.07 | 1.72 | 0.183 | ||

| 2 Weeks later | 3.58±0.06 | 3.59±0.06 | 3.29±0.05 | 9.08 | <0.01 | ||

| t | −3.21 | −3.46 | −0.51 | ||||

| p Valuea | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.613 | ||||

| Change from baselineb | 0.17±0.38 | 0.28±0.54 | 0.35±0.49 | 3.17 | 0.045 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Daily life | |||||||

| Baseline | 3.45±0.08 | 3.32±0.07 | 3.37±0.09 | 0.59 | 0.554 | ||

| 2 Weeks later | 3.62±0.06 | 3.58±0.07 | 3.42±0.07 | 2.67 | 0.073 | ||

| t | −2.56 | −3.12 | −0.55 | ||||

| p Valuea | 0.013 | <0.01 | 0.582 | ||||

| Change from baselineb | 0.18±0.49 | 0.26±0.55 | 0.05±0.58 | 1.82 | 0.166 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Relationship with others or social life | |||||||

| Baseline | 2.88±0.08 | 2.78±0.07 | 2.76±0.08 | 0.713 | 0.492 | ||

| 2 Weeks later | 3.02±0.06 | 3.06±0.08 | 2.68±0.07 | 9.58 | <0.01 | ||

| t | −3.20 | −3.10 | 1.05 | ||||

| p Valuea | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.299 | ||||

| Change from baselineb | 0.14±0.32 | 0.29±0.63 | −0.08±0.54 | 6.43 | <0.01 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Others | |||||||

| Baseline | 3.24±0.07 | 3.14±0.08 | 3.29±0.09 | 0.77 | 0.46 | ||

| 2 Weeks later | 3.36±0.07 | 3.39±0.08 | 3.28±0.06 | 0.66 | 0.521 | ||

| t | −2.47 | −2.41 | 0.08 | ||||

| p Valuea | 0.017 | 0.020 | 0.939 | ||||

| Change from baselineb | 0.12±0.33 | 0.25±0.69 | −0.01±0.55 | 2.66 | 0.073 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Functional Living Index–Cancer | Physical well-being and ability | ||||||

| Baseline | 4.08±0.10 | 4.06±0.11 | 4.23±0.12 | 0.71 | 0.493 | ||

| 2 Weeks later | 4.43±0.09 | 4.45±0.10 | 4.37±0.09 | 0.21 | 0.811 | ||

| t | −2.77 | −2.08 | −1.32 | ||||

| p Valuea | <0.01 | 0.043 | 0.193 | ||||

| Change from baselineb | 0.35±0.89 | 0.39±1.26 | 0.14±0.73 | 0.97 | 0.383 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Emotional state | |||||||

| Baseline | 4.46±0.10 | 4.31±0.10 | 4.48±0.09 | 0.94 | 0.392 | ||

| 2 Weeks later | 4.69±0.07 | 4.78±0.07 | 4.51±0.07 | 3.23 | 0.043 | ||

| t | −3.37 | −3.74 | −0.25 | ||||

| p Valuea | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.800 | ||||

| Change from baselineb | 0.23±0.48 | 0.47±0.84 | 0.23±0.66 | 5.23 | <0.01 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Sociability | |||||||

| Baseline | 4.59±0.24 | 4.27±0.24 | 4.00±0.26 | 1.48 | 0.230 | ||

| 2 Weeks later | 5.16±0.18 | 4.92±0.17 | 4.10±0.25 | 7.73 | <0.01 | ||

| t | −3.33 | −2.66 | −0.35 | ||||

| p Valuea | <0.01 | 0.011 | 0.726 | ||||

| Change from baselineb | 0.57±1.21 | 0.66±1.65 | 0.10±2.01 | 1.59 | 0.208 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Nausea | |||||||

| Baseline | 2.75±0.21 | 2.86±0.23 | 3.41±0.24 | 2.57 | 0.080 | ||

| 2 Weeks later | 3.41±0.18 | 3.77±0.23 | 3.11±0.20 | 2.53 | 0.083 | ||

| t | −4.00 | −3.02 | 1.90 | ||||

| p Valuea | <0.01 | <0.01 | 0.063 | ||||

| Change from baselineb | 0.66±1.17 | 0.91±2.03 | −0.30±1.12 | 9.12 | <0.01 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Hardship because of cancer | |||||||

| Baseline | 3.53±0.13 | 3.47±0.13 | 3.47±0.11 | 0.72 | 0.930 | ||

| 2 Weeks later | 3.71±0.10 | 3.73±0.117 | 3.51±0.11 | 1.28 | 0.281 | ||

| t | −1.11 | −1.27 | −0.40 | ||||

| p Valuea | 0.271 | 0.210 | 0.693 | ||||

| Change from baselineb | 0.18±1.14 | 0.26±1.37 | 0.04±0.71 | 0.49 | 0.614 | ||

Significant values shown in boldface type.

Mean and deviation of the differences between baseline and 2 weeks later.

Changes from Baseline to 2 Weeks

Compared with the ctrl group, the ic-mt and gc-mt groups both had significantly higher scores for the confrontation dimension and lower scores for the avoidance and suppression and resignation dimensions of the ccmq after the intervention. The ctrl group showed no significant change in any dimension of the ccmq after 2 weeks.

In both intervention groups, psychological adjustment, as measured by the pascp, increased significantly on all subscales after the intervention; the ctrl group showed no significant changes in any subscale.

After the intervention, quality of life, as measured by the flic, was significantly increased in both intervention groups for all subscales except hardship. The ctrl group showed no significant changes.

Changes in Outcome Measures After 2 Weeks

The results showed that, compared with the ctrl group, the ic-mt and gc-mt groups both scored significantly higher for the confrontation dimension and lower for the resignation dimension of the ccmq after the intervention. The mean scores for the self-perception and relationships with others dimensions of the pascp were significantly higher in the ic-mt and gc-mt groups than in the ctrl group. The mean scores for the dimensions of nausea, emotional state, and sociability on the flic were significantly higher in both intervention groups than in the ctrl group. However, based on the Tukey honest significant difference, we observed no significant differences in any score for any measured variable between the two intervention groups.

Change from Baseline in Outcome Measurements for the Study Groups

The means of the difference from baseline to 2 weeks for the confrontation and resignation dimensions of the ccmq, the self-perception and relationships with others dimensions of the pascp, and the emotional state and nausea dimensions of the flic were significantly greater in both intervention groups than in the ctrl group. However, no significant differences between the two treatment groups were observed.

Relationship Between Changes in Quality of Life and Psychological Coping Modes and Adjustment

We conducted Pearson correlation tests for the changes from baseline on the flic and on the ccmq and pascp to probe possible mechanisms. The results showed that, in the ic-mt group, the mean change from baseline for the dimensions of emotional state and nausea on the flic correlated significantly with the change in resignation on the ccmq (correlation coefficient: –0.379 and –0.363 respectively, both p < 0.01). In the gc-mt group, the mean change from baseline in the dimensions of physical well-being and ability on the flic was significantly correlated with the change from baseline in the dimensions of avoidance and suppression and resignation on the ccmq. The mean change in the dimension of emotional state on the flic was significantly correlated with the change in the dimensions of confrontation on the ccmq and of impact on emotion or self-esteem on the pascp. The mean change in the dimension of nausea on the flic was significantly correlated with the mean change in self-perception on the pascp. The correlation coefficients were –0.324, –0.393, 0.337, 0.446, and –0.294 respectively (all p < 0.01 or p < 0.05).

Survival Rate

Telephone interviews were conducted to measure the survival rates for the ic-mt group (n = 32) and the ctrl group (n = 32) at 12 and 24 months after the intervention. At 12 months, 6 patients in each group had died, for a survival rate of 81.25%. At 24 months, 5 patients in the ic-mt group and 3 in the ctrl group were still living. Of those living patients, 1 in the ic-mt group reported “living very well.” The survival rate was 31.84% in the ic-mt group and 9.375% in the ctrl group.

DISCUSSION

Our study suggests that using either ic-mt and gc-mt for patients with advanced lung cancer results in significant improvements in quality of life and psychological adjustment. Both techniques can also help patients to modify their coping mode to an effective and positive style. The analysis revealed that all functional dimensions of the pascp and most dimensions of the flic showed great improvement after the intervention in the ic-mt group and the gc-mt group alike, but that the magnitude of the effect did not differ significantly between those groups.

Either cmt intervention could be useful in encouraging the emotional adaptation process to the multiple challenges that patients must face. It could potentially improve the physical, psychological, and social well-being of the patients directly or by triggering their own understanding and insight to achieve improvements. The Pearson correlation analysis of changes from baseline in the indicators for the study groups showed that the improvements in psychological coping mode and adjustment might be the factors driving the improvements in quality of life. The study found that, post-intervention, the survival rate at 24 months was higher in the ic-mt group than in the ctrl group, but because only 32 patients were allocated to each group, the effects of magnanimous therapy on survival requires further study.

Our study showed that cmt was as effective in treating patients with lung cancer as computer magnanimous–relaxed therapy was in treating patients with breast cancer25– 27. However, our previous research did not record and analyze the patient survival rate and its mechanisms. The differences in the present study compared with other related research include the cmt focus on arousing and raising a client’s insights and understanding of life to achieve potentially active and long-term effects; the rich audiovisual content of cmt psychotherapy, whose enjoyable and interesting nature make for better compliance; and the rarity of similar research that has considered even a very simple exploration of the survival rate10–18.

We attempted to elicit differences in the effects of ic-mt and gc-mt so as to distinguish their application, but we found no significant differences between the techniques during this study. That observation suggests that the type of therapy can be chosen according to the patient’s clinical needs.

Following the recommendations of Newell et al. and the revised consort statement10,37, we have clearly detailed our study procedures and tried our best to control factors that might affect the study. In the treatment population, all patient disposition and clinical characteristics were accounted for. In addition, up to 30 patients were enrolled per treatment arm. The types of interventions and number of sessions were described.

We report the first controlled study to assess the effectiveness of ic-mt and gc-mt on measures of psychological coping modes, adjustment, and living function for patients with advanced lung cancer. The research revealed that either cmt intervention could modulate emotion arousal and mind–body interactions, which is crucial in the field of oncology38,39.

In patients with advanced lung cancer, cmt was effective in improving well-being and enhancing survival. Moreover, it appears to be both relatively easy to administer and cost-effective, which are benefits for implementation into practice.

Several limitations in the present study might have contributed to the failure to find long-term effects. Our strict inclusion and exclusion criteria lowered our sample size and reduced the statistical power to find both long-term and short-term effects. The sample used to probe the survival rate was relatively small. The differences in effect between ic-mt and gc-mt require further study.

CONCLUSIONS

We demonstrated that ic-mt and gc-mt can both result in beneficial short-term effects on psychological coping, adjustment, and living function for patients with lung cancer. Moreover, ic-mt and gc-mt seem to be equally beneficial. Further research with larger samples is clearly needed to better understand the biopsychosocial and survival efficacy mechanisms provided by ic-mt and gc-mt.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by a grant from the Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81372488). We thank the patients and oncologists for their contributions.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

We have read and understood Current Oncology’s policy on disclosing conflicts of interest, and we declare that we have none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Diaz-Frutos D, Baca-Garcia E, Garcia-Foncilas J, Lopez-Castroman J. Predictors of psychological distress in advanced cancer patients under palliative treatments. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2016;25:608–15. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown DJ, McMillan DC, Milroy R. The correlation between fatigue, physical function, the systemic inflammatory response, and psychological distress in patients with advanced lung cancer. Cancer. 2005;103:377–82. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mosher CE, Ott MA, Hanna N, Jalal SI, Champion VL. Coping with physical and psychological symptoms: a qualitative study of advanced lung cancer patients and their family caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:2053–60. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2566-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang S, Dai M, Ren JS, Chen YH, Guo LW. Estimates and prediction on incidence, mortality and prevalence of lung cancer in China in 2008 [Chinese] Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2012;33:391–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pozo CL, Morgan MA, Gray JE. Survivorship issues for patients with lung cancer. Cancer Control. 2014;21:40–50. doi: 10.1177/107327481402100106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388:1659–724. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31679-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Piantadosi S. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology. 2001;10:19–28. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200101/02)10:1<19::AID-PON501>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akechi T, Okuyama T, Akizuki N, et al. Course of psychological distress and its predictors in advanced non–small cell lung cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2006;15:463–73. doi: 10.1002/pon.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li J, Girgis A. Supportive care needs: are patients with lung cancer a neglected population? Psychooncology. 2006;15:509–16. doi: 10.1002/pon.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newell SA, Sanson-Fisher RW, Savolainen NJ. Systematic review of psychological therapies for cancer patients: overview and recommendations for future research. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:558–84. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.8.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams S, Dale J. The effectiveness of treatment for depression/ depressive symptoms in adults with cancer: a systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:372–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osborn RL, Demoncada AC, Feuerstein M. Psychosocial interventions for depression, anxiety, and quality of life in cancer survivors: meta-analyses. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006;36:13–34. doi: 10.2190/EUFN-RV1K-Y3TR-FK0L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobsen PB, Donovan KA, Vadaparampil ST, Small BJ. Systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological and activity-based interventions for cancer-related fatigue. Health Psychol. 2007;26:660–7. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kangas M, Bovbjerg DH, Montgomery GH. Cancer-related fatigue: a systematic and meta-analytic review of non-pharmacological therapies for cancer patients. Psychol Bull. 2008;134:700–41. doi: 10.1037/a0012825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devine EC. Meta-analysis of the effect of psychoeducational interventions on pain in adults with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2003;30:75–89. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.75-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwekkeboom KL, Abbott-Anderson K, Wanta B. Feasibility of a patient-controlled cognitive-behavioral intervention for pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbance in cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37:E151–9. doi: 10.1188/10.ONF.E151-E159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graves KD. Social cognitive theory and cancer patients’ quality of life: a meta-analysis of psychosocial intervention components. Health Psychol. 2003;22:210–19. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Badr H, Smith CB, Goldstein NE, Gomez JE, Redd WH. Dyadic psychosocial intervention for advanced lung cancer patients and their family caregivers: results of a randomized pilot trial. Cancer. 2015;121:150–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang X. Magnanimous Therapy [Chinese] Beijing, China: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deimling GT, Albitz C, Monnin K, et al. Personality and psychological distress among older adult, long-term cancer survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2017;35:17–31. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2016.1225145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu H, Liu G, Huang X. Research on the psychological characteristics of cancer long-term survivors. Chin J Behav Med Brain Sci. 2012;21:994–6. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu G. Research on the Psychosomatic Status of Cancer Long-Term Survivors [Master’s thesis, Chinese] Guangdong Pharmaceutical University; Guangzhou: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keating NL, Nørredam M, Landrum MB, Huskamp HA, Meara E. Physical and mental status of older long term cancer survivors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:2045–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deimling GT, Wagner LJ, Bowman KF, Sterns S, Kercher K, Kahana B. Coping among older-adult, long-term cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2006;15:143–59. doi: 10.1002/pon.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qian L. Individual Computer Magnanimous–Relaxed Therapy and Effect of Its Use in Breast Cancer [Master’s thesis, Chinese] Guangdong Pharmaceutical University; Guangzhou: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li R, Huang X, Li Y, Wang X. Effect of group computer magnanimous–relaxed therapy in coping and adjustment in breast cancer. Zhongguo Lin Chuang Yan Jiu. 2017;30:1718–20. 1723. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li R. Group Computer Magnanimous–Relaxed Therapy and Effect of Its Use in Breast Cancer [Master’s thesis, Chinese] Guangdong Pharmaceutical University; Guangzhou: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu H. Individual Gaming Edition Enterprising–Magnanimous–Relaxed Therapy and Effect of Its Use in Depression [Master’s thesis, Chinese] Guangdong Pharmaceutical University; Guangzhou: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang R, Huang X, Zhang Z, Zhang W, Qian L, Pang R. Effect of magnanimous–relaxation therapy on psychosomatic symptoms in young and middle-aged patients with hypertension [Chinese] Guangdong Medicine. 2013;34:1190–3. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang X, Guo B, Wang X, Zhang Y, Lv B. Development and evaluation of the Cancer Coping Modes Questionnaire [Chinese] Chinese Mental Health Journal. 2007;121:517–20. 525. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang X, Wang X, Zhang Y, Lv B, Guo B. Development and evaluation of the Psychological Adjustment Scale for cancer patients [Chinese] Chinese Mental Health Journal. 2007;121:521–5. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schipper H, Clinch J, McMurray A, Levitt M. Measuring the quality of life of cancer patients: the Functional Living Index–Cancer: development and validation. J Clin Oncol. 1984;2:472–83. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1984.2.5.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang X. Brief introduction to commonly used quality of life measurement scales [Chinese] Chin J Behav Med Sci. 2000;9:69. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fong DY, Lee AH, Tung SY, et al. The Functional Living Index– Cancer is a reliable and valid instrument in Chinese cancer patients. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:311–16. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0456-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cai G, Zhang M, Zhang S, Wang J, Zhou T. Application validity of the mmse and bdrs. Chin J Neuropsychiatric Dis. 1988;14:298–9. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-Mental State” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moher D, Schulz K, Altman D. The consort statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. Lancet. 2001;357:1191–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04337-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wahbeh H, Haywood A, Kaufman K, Zwickey H. Mind–body medicine and immune system outcomes: a systematic review. Open Complement Med J. 2009;1:25–34. doi: 10.2174/1876391X00901010025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gordon LG, Beesley VL, Scuffham PA. Evidence on the economic value of psychosocial interventions to alleviate anxiety and depression among cancer survivors: a systematic review. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2011;7:96–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-7563.2011.01395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]