Abstract

Background

Screening the cardiovascular system is an important and necessary component of the physical therapist examination to ensure patient safety, appropriate referral, and timely medical management of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and risk factors. The most basic screening includes a measurement of resting blood pressure (BP) and heart rate (HR). Previous work demonstrated that rates of BP and HR screening and perceptions toward screening by physical therapists are inadequate.

Objective

The purpose was to assess the current attitudes and behaviors of physical therapists in the United States regarding the screening of patients for CVD or risk factors in outpatient orthopedic practice.

Design

This was a cross-sectional, online survey study.

Methods

Data were collected from an anonymous adaptive online survey delivered via an email list.

Results

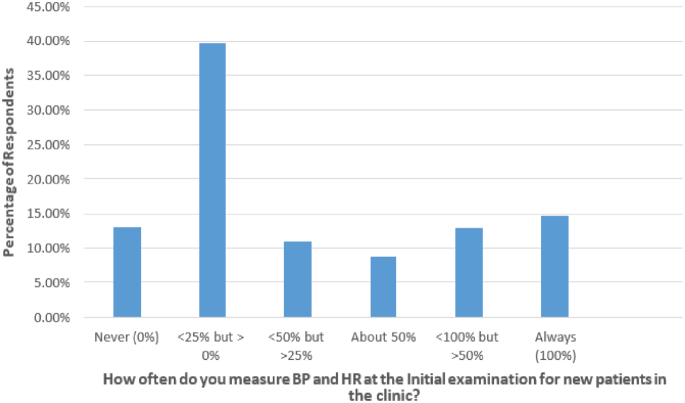

A total of 1812 surveys were included in this analysis. A majority of respondents (n = 931; 51.38%) reported that at least half of their current caseload included patients either with diagnosed CVD or at moderate or greater risk of a future occurrence. A total of 14.8% of respondents measured BP and HR on the initial examination for each new patient. The most commonly self-reported barriers to screening were lack of time (37.44%) and lack of perceived importance (35.62%). The most commonly self-reported facilitators of routine screening were perceived importance (79.48%) and clinic policy (38.43%). Clinicians who managed caseloads with the highest CVD risk were the most likely to screen.

Limitations

Although the sampling population included was large and representative of the profession, only members of the American Physical Therapy Association Orthopaedic Section were included in this survey.

Conclusions

Despite the high prevalence of patients either diagnosed with or at risk for CVD, few physical therapists consistently included BP and HR on the initial examination. The results of this survey suggest that efforts to improve understanding of the importance of screening and modifications of clinic policy could be effective strategies for improving rates of HR and BP screening.

Screening the cardiovascular system is an important and necessary component of the physical therapist examination to ensure patient safety, appropriate referral, and timely medical management. The most basic screening includes a measurement of resting blood pressure (BP) and heart rate (HR).1 Both of these brief examinations provide invaluable data regarding the stability of the cardiovascular system. Abnormalities in either measure are associated with increased mortality, and these measures can assist with clinical decision-making and differential diagnosis. For example, the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality increases linearly with each 10 beats-per-minute increase in resting HR.2 This relationship between resting HR and mortality is independent of other cardiovascular risk factors and becomes particularly significant with a resting HR above 90 beats per minute.2 Elevated resting BP (hypertension: HTN) is a significant modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and is present in approximately 34% of the US population.3,4 Large epidemiological studies and analyses specific to physical therapy have demonstrated that HTN and other cardiovascular risk factors occur frequently in patients with low back pain, hip and knee osteoarthritis, and other common conditions encountered in physical therapist practice.5–9 Boissonault demonstrated that of the comorbidities present in patients referred to outpatient physical therapy services, heart disease and its associated risk factors are the most common, and most patients would be classified as having at least moderate risk for heart disease.10 Unfortunately, HTN is relatively asymptomatic, even at extreme values11, which can make awareness, treatment, and effective control difficult.12,13 Early detection of HTN is important and can result in significant reductions in health care costs, mortality, and morbidity.3,14,15 Studies have demonstrated that CVD screening by nonphysician providers, especially BP screening, can help improve detection and medical management.14,16,17 Outpatient physical therapists can likely assist with this process by routinely including CVD screening on the initial examination for all new patients. With the advent of direct access, physical therapists can serve as first-contact providers for patients seeking medical care, highlighting the need for routine CVD screening.

Despite the high likelihood of encountering a patient in outpatient physical therapist practice with CVD, significant risk factors for CVD, or abnormalities in resting BP or HR, resting measures of BP and HR are not routinely performed.18 In 2002, Frese et al18 surveyed the screening rate and perceptions regarding screening in clinical instructors across a variety of physical therapist practice settings and concluded that physical therapists did not meet the recommendations for physical therapy care described in the Guide to Physical Therapist Practice.19 The majority of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed (59.5%) that measurement of HR and BP should be included in physical therapy screening.18 However, few respondents reported measuring HR and BP “always” on new patients (6% and 4.4%, respectively); 79.9% and 83% reported measuring HR and BP less than half the time, respectively, including substantial percentages who never measured HR or BP (38% and 43%, respectively).18 This study, however, used an internal survey model limited to clinical instructors affiliated with the authors’ host institution, and the majority of surveys came from physical therapists practicing in nonoutpatient settings. In the outpatient setting, physical therapists are most likely to encounter a patient in a direct-access scenario without close physiological monitoring and might serve as the first entry point to the health care system. Additionally, since these findings were published, there have been significant changes in entry-level (professional) physical therapist education and in postprofessional training (ie, clinical residencies and fellowships), and more physical therapists are practicing in states with direct access. Given these factors, it is critical to investigate the CVD screening rate and perceptions toward screening in a large sample specifically of outpatient physical therapists using an external survey, and to determine whether or not these changes in policy, practice, and education have translated into changes in behaviors and perceptions regarding CVD screening. The purpose of the study was to assess the current attitudes and behaviors of outpatient physical therapists in the United States toward the screening of CVD or its risk factors and to determine the factors influencing screening rates.

Methods

Survey Formulation

The piloting and review process followed procedures similar to those of Frese et al,18 where no specific measure of reliability and validity was obtained. The survey was reviewed and piloted by a representative group of 5 actively licensed outpatient physical therapists practicing in the United States for different lengths of practice; 3 of the therapists had practiced for 0 to 5 years, 1 for 7 years,, and 1 for more than 20 years. This group of outpatient physical therapists reviewed the survey items and completed pilot versions of the survey questionnaire 4 times over 1 year. Their feedback and suggestions were incorporated into each new pilot version of the survey that they completed. Following the final round of piloting and feedback, the final version of the survey was formulated and distributed across the email list for this study. This adaptive online survey consisted of 30 multiple choice questions that assessed demographics, clinical decision-making, CVD-risk screening behaviors, and rationale (see eAppendix, available at https://academic.oup.com/ptj).

Distribution Procedure

The survey was disseminated across the American Physical Therapy Association Orthopaedic Section email list and was administered using Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT, USA). The survey was distributed over a period of 8 weeks, with completion reminders sent weekly. Data were collected anonymously. Access to the survey was limited to respondents having the password, which was provided in the distributed email. Respondents were limited to a single response matched to the link provided in the distributed email and the survey could not be indexed into search engines.

All participants were consented prior to initiating the survey. The inclusion criteria were: actively licensed physical therapists in the United States and members of the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. The exclusion criteria were: not currently licensed as a physical therapist in the United States. Incomplete surveys and responses from therapists practicing in nonoutpatient settings were excluded from this analysis. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed on respondent demographics and responses to each survey question (Tab. 1). Cross-tabulations with χ2 analyses and histograms were performed to compare the differences in the likelihood of screening between different groups of responses for each major covariate (Tab. 2 and Tab. 3). Univariate ordinal logistic regression was then performed to assess which factors most strongly contributed to the likelihood of screening and their significance (Tab. 4). To correct for difference among factors, a multivariate analysis was also performed (Tab. 5). Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Analysis Software version 9.4 (SAS Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

Table 1.

Demographics of Survey Participants (N = 1812)a

| Characteristic | No. of Participants | % of Participants |

|---|---|---|

| Location | ||

| Alaska/Hawaii | 26 | 1.4 |

| Northeast | 415 | 22.9 |

| Mid-North | 532 | 29.4 |

| Northwest | 213 | 11.7 |

| Southeast | 226 | 12.5 |

| Mid-South | 206 | 11.4 |

| Southwest | 185 | 10.2 |

| Other | 9 | 0.5 |

| Years practicing | ||

| 0–5 | 363 | 20.0 |

| 6–10 | 294 | 16.2 |

| 11–15 | 220 | 12.1 |

| 16–20 | 235 | 13.0 |

| > 20 | 700 | 38.6 |

| Highest level of physical therapy education | ||

| Bachelor's degree (BSPT) | 283 | 15.6 |

| Master's degree (MSPT) | 338 | 18.7 |

| Clinical doctorate (DPT or tDPT) | 1191 | 65.7 |

| Terminal doctorate | ||

| Yes | 146 | 8.1 |

| No | 1666 | 91.9 |

| Residency or fellowship | ||

| Yes | 363 | 20.0 |

| No | 1449 | 80.0 |

| Certificationb | ||

| OCS | 848 | 46.8 |

| FAAOMPT | 114 | 6.3 |

| SCS | 62 | 3.4 |

| GCS | 11 | 0.6 |

| NCS | 7 | 0.4 |

| WCS | 7 | 0.4 |

| PCS | 2 | 0.1 |

| CCS | 1 | 0.1 |

| ECS | 0 | 0 |

| None | 888 | 49.0 |

| Patient age range, y | ||

| < 18 | 22 | 1.2 |

| 18–25 | 52 | 2.9 |

| 26–35 | 74 | 4.1 |

| 36–45 | 323 | 17.8 |

| 46–55 | 622 | 34.3 |

| > 55 | 642 | 35.4 |

| Not sure | 77 | 4.2 |

| Evaluation of new patients | ||

| Never | 433 | 23.9 |

| < 1 time/mo | 293 | 16.2 |

| 1 time/mo | 147 | 8.1 |

| 2 or 3 times/mo | 198 | 10.9 |

| 1 time/wk | 191 | 10.5 |

| 2 or 3 times/wk | 211 | 11.6 |

| Not daily but > 3 times/wk | 156 | 8.6 |

| Daily | 183 | 10.1 |

| Risk caseload | ||

| None of my patients (0%) | 30 | 1.7 |

| < 25% but > 0% of my caseload | 363 | 20.0 |

| < 50% but > 25% of my caseload | 488 | 26.9 |

| ∼ 50% of my caseload | 400 | 22.1 |

| Not all but > 50% of my caseload | 514 | 28.4 |

| All of my patients (100%) | 17 | 0.9 |

| Format of cardiopulmonary assessment and treatment in physical therapy school | ||

| Integrated within another course | 369 | 20.4 |

| Half-semester course | 160 | 8.8 |

| Full-semester course | 1021 | 56.3 |

| Other | 54 | 3.0 |

| Not sure | 208 | 11.5 |

| Background of director of cardiopulmonary course in physical therapy schoolb | ||

| A non–physical therapist with a PhD/DSc in exercise physiology or a related field | 87 | 4.8 |

| A nurse (RN) | 14 | 0.8 |

| A physician (MD or DO) | 74 | 4.1 |

| A physician assistant or nurse practitioner | 7 | 0.4 |

| A physical therapist with 5 + y of experience treating patients with cardiopulmonary diseases | 726 | 40.1 |

| A physical therapist with a cardiovascular and pulmonary clinical specialization (CCS) | 536 | 29.6 |

| A physical therapist with a PhD/DSc in exercise physiology or a related field | 608 | 33.6 |

| A physical therapist without any of the above-listed qualifications or experiences | 133 | 7.3 |

| Not sure | 404 | 22.3 |

BSPT = Bachelor of Science in Physical Therapy; CCS = Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Certified Specialist; DPT = Doctor of Physical Therapy; ECS = Clinical Electrophysiological Certified Specialist; FAAOMPT = Fellow of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Manual Physical Therapists; GCS = Geriatric Certified Specialist; MSPT = Master of Science in Physical Therapy; NCS = Neurologic Certified Specialist; OCS = Orthopedic Certified Specialist; PCS = Pediatric Certified Specialist; SCS = Sports Certified Specialist; tDPT = Transitional DPT; WCS = Women's Health Certified Specialist.

The number exceeded 1812 because participants could select multiple options.

Table 2.

χ2 Analysis of Potential Covariatesa

| Covariate | Collection of Blood Pressure and Heart Rateb | P | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never (0%) | < 25% but > 0% of the Time | < 50% but > 25% of the Time | ∼ 50% of the Time | Not always but > 50% of the Time | Always (100%) | Total | |||||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Years practicing | .3801 | ||||||||||||||

| 0–5 | 48 | 13.2 | 162 | 44.6 | 37 | 10.2 | 26 | 7.2 | 44 | 12.1 | 46 | 12.7 | 363 | 20.0 | |

| 6–10 | 46 | 15.6 | 122 | 41.5 | 29 | 9.9 | 25 | 8.5 | 36 | 12.2 | 36 | 12.2 | 294 | 16.2 | |

| 11–15 | 27 | 12.3 | 96 | 43.6 | 22 | 10.0 | 23 | 10.5 | 22 | 10.0 | 30 | 13.6 | 220 | 12.1 | |

| 16–20 | 27 | 11.5 | 96 | 40.9 | 26 | 11.1 | 21 | 8.9 | 27 | 11.5 | 38 | 16.2 | 235 | 13.0 | |

| > 20 | 88 | 12.6 | 246 | 35.1 | 83 | 11.9 | 61 | 8.7 | 104 | 14.9 | 118 | 16.9 | 700 | 38.6 | |

| Highest level of physical therapy education | .1853 | ||||||||||||||

| Bachelor's degree (BSPT) | 46 | 16.3 | 106 | 37.5 | 39 | 13.8 | 22 | 7.8 | 33 | 11.7 | 37 | 13.1 | 283 | 15.6 | |

| Master's degree (MSPT) | 41 | 12.1 | 147 | 43.5 | 42 | 12.4 | 27 | 8.0 | 41 | 12.1 | 40 | 11.8 | 338 | 18.7 | |

| Clinical doctorate (DPT or tDPT) | 149 | 12.5 | 469 | 39.4 | 116 | 9.7 | 107 | 9.0 | 159 | 13.4 | 191 | 16.0 | 1191 | 65.7 | |

| Terminal doctorate | .0182 | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 15 | 10.3 | 43 | 29.5 | 19 | 13.0 | 12 | 8.2 | 25 | 17.1 | 32 | 21.9 | 146 | 8.1 | |

| No | 221 | 13.3 | 679 | 40.8 | 178 | 10.7 | 144 | 8.6 | 208 | 12.5 | 236 | 14.2 | 1666 | 91.9 | |

| Residency or fellowship | .0718 | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 40 | 11.0 | 144 | 39.7 | 35 | 9.6 | 26 | 7.2 | 47 | 12.9 | 71 | 19.6 | 363 | 20.0 | |

| No | 196 | 13.5 | 578 | 39.9 | 162 | 11.2 | 130 | 9.0 | 186 | 12.8 | 197 | 13.6 | 1449 | 80.0 | |

| Certification | .0645 | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 113 | 12.2 | 372 | 40.3 | 94 | 10.2 | 72 | 7.8 | 113 | 12.2 | 160 | 17.3 | 924 | 51.0 | |

| No | 123 | 13.9 | 350 | 39.4 | 103 | 11.6 | 84 | 9.5 | 120 | 13.5 | 108 | 12.2 | 888 | 49.0 | |

| Patient age range,c y | .0009 | ||||||||||||||

| < 18–25 | 16 | 21.6 | 36 | 48.6 | 7 | 9.5 | 5 | 6.8 | 5 | 6.8 | 5 | 6.8 | 74 | 4.1 | |

| 26–35 | 11 | 14.9 | 34 | 45.9 | 3 | 4.1 | 6 | 8.1 | 10 | 13.5 | 10 | 13.5 | 74 | 4.1 | |

| 36–45 | 54 | 16.7 | 124 | 38.4 | 25 | 7.7 | 31 | 9.6 | 39 | 12.1 | 50 | 15.5 | 323 | 17.8 | |

| 46–55 | 90 | 14.5 | 245 | 39.4 | 79 | 12.7 | 46 | 7.4 | 67 | 10.8 | 95 | 15.3 | 622 | 34.3 | |

| > 55 | 57 | 8.9 | 246 | 38.3 | 71 | 11.1 | 62 | 9.7 | 107 | 16.7 | 99 | 15.4 | 642 | 35.4 | |

| Direct-access evaluation | .3557 | ||||||||||||||

| Never | 45 | 10.4 | 191 | 44.1 | 44 | 10.2 | 33 | 7.6 | 55 | 12.7 | 65 | 15.0 | 433 | 23.9 | |

| < 1 time/mo | 45 | 15.4 | 115 | 39.2 | 31 | 10.6 | 26 | 8.9 | 37 | 12.6 | 39 | 13.3 | 293 | 16.2 | |

| 1 time/mo | 23 | 15.6 | 54 | 36.7 | 14 | 9.5 | 14 | 9.5 | 20 | 13.6 | 22 | 15.0 | 147 | 8.1 | |

| 2 or 3 times/mo | 26 | 13.1 | 79 | 39.9 | 32 | 16.2 | 11 | 5.6 | 29 | 14.6 | 21 | 10.6 | 198 | 10.9 | |

| 1 time/wk | 20 | 10.5 | 70 | 36.6 | 14 | 7.3 | 21 | 11.0 | 23 | 12.0 | 43 | 22.5 | 191 | 10.5 | |

| 2 or 3 times/wk | 28 | 13.3 | 88 | 41.7 | 25 | 11.8 | 18 | 8.5 | 27 | 12.8 | 25 | 11.8 | 211 | 11.6 | |

| Not daily but > 3 times/wk | 19 | 12.2 | 58 | 37.2 | 20 | 12.8 | 17 | 10.9 | 18 | 11.5 | 24 | 15.4 | 156 | 8.6 | |

| Daily | 30 | 16.4 | 67 | 36.6 | 17 | 9.3 | 16 | 8.7 | 24 | 13.1 | 29 | 15.8 | 183 | 10.1 | |

| Risk evaluation | <.0001 | ||||||||||||||

| Never | 10 | 25.6 | 19 | 48.7 | 1 | 2.6 | 3 | 7.7 | 3 | 7.7 | 3 | 7.7 | 39 | 2.2 | |

| < 1 time/mo | 30 | 22.1 | 64 | 47.1 | 11 | 8.1 | 10 | 7.4 | 9 | 6.6 | 12 | 8.8 | 136 | 7.5 | |

| 2 or 3 times/mo | 32 | 18.9 | 71 | 42.0 | 19 | 11.2 | 14 | 8.3 | 18 | 10.7 | 15 | 8.9 | 169 | 9.3 | |

| 1 time/wk | 29 | 13.2 | 93 | 42.5 | 23 | 10.5 | 21 | 9.6 | 24 | 11.0 | 29 | 13.2 | 219 | 12.1 | |

| 2 or 3 times/wk | 49 | 13.0 | 156 | 41.5 | 43 | 11.4 | 26 | 6.9 | 55 | 14.6 | 47 | 12.5 | 376 | 20.7 | |

| Not daily but > 3 times/wk | 41 | 12.1 | 136 | 40.0 | 38 | 11.2 | 25 | 7.4 | 42 | 12.4 | 58 | 17.1 | 340 | 18.8 | |

| Daily | 45 | 8.4 | 183 | 34.3 | 62 | 11.6 | 57 | 10.7 | 82 | 15.4 | 104 | 19.5 | 533 | 29.4 | |

| Risk caseload | <.0001 | ||||||||||||||

| None of my patients (0%) | 11 | 36.7 | 13 | 43.3 | 2 | 6.7 | 2 | 6.7 | 1 | 3.3 | 1 | 3.3 | 30 | 1.7 | |

| < 25% but > 0% | 65 | 17.9 | 191 | 52.6 | 23 | 6.3 | 24 | 6.6 | 29 | 8.0 | 31 | 8.5 | 363 | 20.0 | |

| < 50% but > 25% | 78 | 16.0 | 185 | 37.9 | 66 | 13.5 | 40 | 8.2 | 62 | 12.7 | 57 | 11.7 | 488 | 26.9 | |

| ∼ 50% of my caseload | 41 | 10.3 | 149 | 37.3 | 51 | 12.8 | 43 | 10.8 | 46 | 11.5 | 70 | 17.5 | 400 | 22.1 | |

| Not all but > 50% | 39 | 7.6 | 183 | 35.6 | 54 | 10.5 | 47 | 9.1 | 89 | 17.3 | 102 | 19.8 | 514 | 28.4 | |

| All of my patients (100%) | 2 | 11.8 | 1 | 5.9 | 1 | 5.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 35.3 | 7 | 41.2 | 17 | 0.9 | |

| Cardiopulmonary course formatc | .0952 | ||||||||||||||

| Integrated within another course | 48 | 13.0 | 126 | 34.1 | 40 | 10.8 | 34 | 9.2 | 49 | 13.3 | 72 | 19.5 | 369 | 20.4 | |

| Half-semester course | 22 | 13.8 | 57 | 35.6 | 19 | 11.9 | 15 | 9.4 | 29 | 18.1 | 18 | 11.3 | 160 | 8.8 | |

| Full-semester course | 120 | 11.8 | 433 | 42.4 | 104 | 10.2 | 85 | 8.3 | 129 | 12.6 | 150 | 14.7 | 1021 | 56.3 | |

| Other | 3 | 5.6 | 23 | 42.6 | 9 | 16.7 | 4 | 7.4 | 10 | 18.5 | 5 | 9.3 | 54 | 3.0 | |

BSPT = Bachelor of Science in Physical Therapy; DPT = Doctor of Physical Therapy; MSPT = Master of Science in Physical Therapy; tDPT = Transitional DPT.

Data are reported as numbers (No.) and percentages (%) of participants.

The total number was not 1812 because the category “Not sure” was excluded.

Table 3.

Description of Outcome Variables and Relevant Covariate Informationa

| Parameter | No. of Participants | % of Participants |

|---|---|---|

| Reasons for NOT measuring heart rate (HR) and blood pressure (BP)b (n = 1544) | ||

| Equipment not available | 93 | 6.0 |

| Lack of clinic/department/institutional policy | 222 | 14.4 |

| Not certain of ability to perform measurements competently | 18 | 1.2 |

| Not certain of what to do with the information | 107 | 6.9 |

| Lack of time | 578 | 37.4 |

| Not important for my patient population | 550 | 35.6 |

| Other | 414 | 26.8 |

| Reasons for measuring HR and BPb (n = 268) | ||

| Certain of ability to perform these measurements competently | 78 | 29.1 |

| Clinic/department/institutional policy | 103 | 38.4 |

| Important for my patient population | 213 | 79.5 |

| Required for insurance reimbursement | 8 | 3.0 |

| Other | 43 | 16.0 |

| Tests/measures comfortable using to screen cardiovascular stabilityc | ||

| Activity or health history questionnaire (eg, PARQ, DASI) | 743 | 41.0 |

| Anthropometric measurements (body weight, BMI, waist circumference) | 1050 | 57.9 |

| Static (ie, rest and recovery) measures of HR and BP | 1688 | 93.2 |

| RPE | 1371 | 75.7 |

| Exercise testing (eg, CPX, 6MWT, Step Test, Graded Exercise Tolerance Test) | 678 | 37.4 |

| Dynamic/concurrent exercising measurements of HR and BP | 736 | 40.6 |

| Other | 17 | 0.9 |

| None | 22 | 1.2 |

| Measures currently used to screen for heart diseasec | ||

| Anthropometric measurements (body weight, BMI, waist circumference) | 646 | 35.7 |

| Concurrent exercising measurements of HR and BP | 210 | 11.6 |

| Exercise testing (eg, CPX, 6MWT, Step Test, Graded Exercise Tolerance Test) | 313 | 17.3 |

| Validated activity or health history questionnaire (eg, PARQ, DASI) | 301 | 16.6 |

| RPE | 776 | 42.8 |

| Resting HR and BP measurements | 1295 | 71.5 |

| Response and recovery HR and BP measurements | 632 | 34.9 |

| Other | 77 | 4.2 |

| None | 223 | 12.3 |

| Cardiopulmonary assessment equipmentc | ||

| Electronic BP monitor | 1003 | 55.4 |

| Pulse oximeter | 1375 | 75.9 |

| Telemetry device or 12-lead ECG | 40 | 2.2 |

| Sphygmomanometer (BP cuff) | 1704 | 94.0 |

| Stethoscope | 1687 | 93.1 |

| Doppler ultrasound device | 38 | 2.1 |

| Other | 12 | 0.7 |

| None | 20 | 1.1 |

| Exercise equipment (select all that apply) | ||

| 50-cm or 20-in step/platform or standard stairs | 1257 | 69.4 |

| A hallway or floor at least ∼ 30 m (100 ft) long | 1360 | 75.1 |

| NuStepd or reciprocal stepper | 883 | 48.7 |

| Stationary bike | 1698 | 93.7 |

| Treadmill | 1652 | 91.2 |

| Other | 59 | 3.3 |

| None | 17 | 0.9 |

| Where tests and measures used were learned | ||

| Undergraduate studies prior to physical therapist school | 409 | 22.6 |

| Physical therapist school | 1719 | 94.9 |

| Continuing education and in-service or employee training | 713 | 39.3 |

| Self-education (eg, reading manuscripts and texts) | 604 | 33.3 |

| Postprofessional residency or fellowship | 212 | 11.7 |

| Other | 77 | 4.2 |

For 1812 participants unless otherwise noted. BMI = body mass index; CPX = Cardiopulmonary Exercise Test; DASI = Duke Activity Status Index; ECG = electrocardiogram; PARQ = Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire; RPE, rating of perceived exertion; 6MWT = 6-Minute Walk Test.

n is less than 1812 (participants only fell in 1 of these 2 categories).

n exceeds 1812 (participants could select multiple options).

NuStep LLC, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Table 4.

Univariate Ordinal Logistic Regression for Predicting Frequency of Blood Pressure and Heart Rate Collectiona

| Parameter | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |||

| Years practicing | ||||

| 0–5 | ||||

| 6–10 | 0.968 | 0.733 | 1.279 | .8213 |

| 11–15 | 1.065 | 0.787 | 1.441 | .6833 |

| 16–20 | 1.221 | 0.909 | 1.642 | .1847 |

| > 20 | 1.373 | 1.093 | 1.727 | .0066 |

| Highest level of physical therapy education | ||||

| Bachelor's degree (BSPT) | ||||

| Master's degree (MSPT) | 1.024 | 0.770 | 1.362 | .8712 |

| Clinical doctorate (DPT or tDPT) | 1.211 | 0.958 | 1.530 | .1094 |

| Terminal doctorate | ||||

| No | ||||

| Yes | 1.683 | 1.244 | 2.276 | .0007 |

| Residency or fellowship | ||||

| No | ||||

| Yes | 1.238 | 1.008 | 1.522 | .0422 |

| Certification | .1322 | |||

| No | ||||

| Yes | 1.136 | 0.962 | 1.341 | |

| Patient age range, y | ||||

| < 18–25 | ||||

| 26–35 | 1.677 | 0.931 | 3.021 | .0850 |

| 36–45 | 1.851 | 1.164 | 2.943 | .0093 |

| 46–55 | 1.901 | 1.220 | 2.962 | .0045 |

| > 55 | 2.549 | 1.636 | 3.970 | <.0001 |

| Evaluation of new patients | ||||

| Never | ||||

| < 1 time/mo | 0.888 | 0.680 | 1.160 | .3842 |

| 1 time/mo | 0.968 | 0.691 | 1.356 | .8504 |

| 2 or 3 times/mo | 0.901 | 0.666 | 1.220 | .5010 |

| 1 time/wk | 1.364 | 1.005 | 1.849 | .0461 |

| 2 or 3 times/wk | 0.889 | 0.661 | 1.196 | .4356 |

| Not daily but > 3 times/wk | 1.068 | 0.769 | 1.484 | .6932 |

| Daily | 0.953 | 0.698 | 1.301 | .7612 |

| Risk evaluation | ||||

| Never | ||||

| < 1 time/mo | 1.214 | 0.628 | 2.344 | .5646 |

| 2 or 3 times/mo | 1.594 | 0.838 | 3.033 | .1555 |

| 1 time/wk | 2.156 | 1.149 | 4.045 | .0168 |

| 2 or 3 times/wk | 2.241 | 1.218 | 4.126 | .0095 |

| Not daily but > 3 times/wk | 2.559 | 1.386 | 4.726 | .0027 |

| Daily | 3.547 | 1.941 | 6.483 | <.0001 |

| Risk caseload | ||||

| None of my patients (0%) | ||||

| < 25% but > 0% of my caseload | 2.165 | 1.078 | 4.349 | .0299 |

| < 50% but > 25% of my caseload | 3.468 | 1.736 | 6.926 | .0004 |

| ∼ 50% of my caseload | 4.859 | 2.421 | 9.751 | <.0001 |

| Not all but > 50% of my caseload | 6.168 | 3.086 | 12.328 | <.0001 |

| All of my patients (100%) | 19.972 | 6.625 | 60.211 | <.0001 |

| Cardiopulmonary assessment format | ||||

| Integrated within another course | ||||

| Half-semester course | 0.839 | 0.601 | 1.171 | .3024 |

| Full-semester course | 0.800 | 0.646 | 0.991 | .0413 |

| Other | 0.923 | 0.553 | 1.541 | .7597 |

BSPT = Bachelor of Science in Physical Therapy; CI = confidence interval; DPT = Doctor of Physical Therapy; MSPT = Master of Science in Physical Therapy; tDPT = Transitional DPT.

Table 5.

Multivariate Ordinal Logistic Regression for Predicting Frequency of Blood Pressure and Heart Rate Collectiona

| Parameter | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |||

| Years practicing | ||||

| 0–5 | ||||

| 6–10 | 0.953 | 0.713 | 1.274 | .7434 |

| 11–15 | 1.234 | 0.877 | 1.735 | .2278 |

| 16–20 | 1.726 | 1.222 | 2.438 | .0020 |

| > 20 | 2.120 | 1.582 | 2.841 | <.0001 |

| Highest level of physical therapy education | ||||

| Bachelor's degree (BSPT) | ||||

| Master's degree (MSPT) | 1.050 | 0.741 | 1.487 | .7851 |

| Clinical doctorate (DPT or tDPT) | 1.445 | 1.058 | 1.973 | .0205 |

| Terminal doctorate | ||||

| No | ||||

| Yes | 1.854 | 1.329 | 2.586 | .0003 |

| Residency or fellowship | ||||

| No | ||||

| Yes | 1.385 | 1.103 | 1.739 | .0051 |

| Certification | .1000 | |||

| No | ||||

| Yes | 1.182 | 0.969 | 1.442 | |

| Patient age range, y | ||||

| < 18–25 | ||||

| 26–35 | 1.414 | 0.748 | 2.674 | .2869 |

| 36–45 | 1.240 | 0.732 | 2.100 | .4232 |

| 46–55 | 0.976 | 0.578 | 1.647 | .9262 |

| > 55 | 1.104 | 0.648 | 1.879 | .7165 |

| Evaluation of new patients | ||||

| Never | ||||

| < 1 time/mo | 0.811 | 0.602 | 1.091 | .1662 |

| 1 time/mo | 0.925 | 0.638 | 1.340 | .6789 |

| 2 or 3 times/mo | 0.777 | 0.556 | 1.085 | .1380 |

| 1 time/wk | 1.570 | 1.123 | 2.196 | .0084 |

| 2 or 3 times/wk | 1.008 | 0.726 | 1.401 | .9615 |

| Not daily but > 3 times/wk | 1.109 | 0.770 | 1.599 | .5777 |

| Daily | 0.963 | 0.681 | 1.363 | .8335 |

| Risk caseload | ||||

| None of my patients (0%) | ||||

| < 25% but > 0% of my caseload | 1.944 | 0.872 | 4.334 | .1044 |

| < 50% but > 25% of my caseload | 3.491 | 1.540 | 7.911 | .0027 |

| ∼ 50% of my caseload | 4.921 | 2.146 | 11.283 | .0002 |

| Not all but > 50% of my caseload | 6.833 | 2.984 | 15.642 | <.0001 |

| All of my patients (100%) | 19.484 | 5.400 | 70.299 | <.0001 |

| Cardiopulmonary assessment format | ||||

| Integrated within another course | ||||

| Half-semester course | 0.941 | 0.663 | 1.336 | .7341 |

| Full-semester course | 0.964 | 0.762 | 1.219 | .7589 |

| Other | 1.079 | 0.636 | 1.829 | .7779 |

BSPT = Bachelor of Science in Physical Therapy; CI = confidence interval; DPT = Doctor of Physical Therapy; MSPT = Master of Science in Physical Therapy; tDPT = Transitional DPT.

Results

Responses

Over a period of 8 weeks a total of 16,551 surveys were distributed, and 2461 surveys were initiated with a total response rate of 14.87%. A total of 2141 surveys were completed yielding a completion rate of 86.9%. Surveys from respondents practicing in nonoutpatient settings were excluded from this analysis, leaving a total of 1812 surveys included in this analysis.

Respondent Demographics

The geographical distribution of survey respondents is provided in Table 1. The regions with the largest number of respondents were the Mid-North (n = 532; 29.4%) and Northeast (n = 415; 22.9%). Nine respondents (0.05%) completed the survey while outside the United States or in commonwealths and were still included in the analysis. The majority of respondents had practiced for more than 20 years (n = 700; 38.6%), followed by 0 to 5 years (n = 363; 20%); the smallest group were clinicians practicing 11 to 15 years (12.1%). Despite the demographics for years of practice, the most represented physical therapy degree was the clinical doctorate (Doctor of Physical Therapy [DPT]/Transitional DPT [tDPT]) (n = 1191; 65.7%). Very few respondents had earned terminal doctoral degrees (PhD, DSc, EdD, etc) (n = 146; 8.1%). Only 20% had completed an accredited physical therapy residency or fellowship program (n = 363); however, a large percentage of respondents had earned board-certified specializations (n = 810; 44.7%), with orthopedics being the most common (n = 848; 46.8%); 114 (6.3%) respondents were Fellows of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Manual Physical Therapists. The majority of respondents reported that their cardiopulmonary assessment course in physical therapy school was a full-semester course (n = 1021; 56.3%), and 1712 (94.5%) reported learning the cardiopulmonary assessments they currently use while in their physical therapy entry-level academic program. However, only 29.6% (n = 536) reported that their professor had held a board specialization in cardiopulmonary physical therapy, and 33.6% (n = 608) reported that their professor had held a terminal degree.

Caseload

Most respondents reported that the most common age group in their caseload was over 46 years old: 46 to 55 years old (n = 622; 34.3%) and greater than 55 years old (n = 642; 35.4%). Only 22 (1.2%) respondents reported that the most common age group in their caseload was under 18 years old. These age demographics are similar to previously published work on use of outpatient rehabilitation services.20 Regarding risk factors, the majority of respondents (n = 931; 51.38%) reported that at least half of their current caseload included patients either with diagnosed CVD or at moderate or greater risk for CVD; 28.37% (n = 514) reported that more than 50% of their current caseload was either diagnosed with CVD or at moderate or greater risk for CVD. Similar percentages were reported for new patients evaluated, with the majority of respondents (n = 1249; 68.9%) reporting encountering at least twice per week a new patient either diagnosed with CVD or at moderate or greater risk for CVD; 29.4% (n = 533) reported encountering such patients daily. Notably, a large proportion of respondents (48.2%; n = 873) reported examining a patient in a direct-access scenario once per month or less, and 23.9% (n = 433) reported never examining patients via direct access.

Screening Behaviors

Only 14.8% (n = 268) of respondents reported measuring resting HR and BP on the initial examination for every new patient (Figure). In total, 63.74% (n = 1115) of respondents reported measuring HR and BP less than 50% of the time, 39.8% (n = 722) reported less than 25% of the time, and 13.0% (n = 236) reported never measuring. The most commonly reported facilitators to routine screening were perceived importance (79.48%) and clinic policy (38.43%). The most commonly reported barriers to routine screening were lack of time (37.44%) and a lack of perceived importance (35.62%). The majority of respondents reported that their clinic possessed the necessary equipment to screen (BP cuff and stethoscope) and that they felt competent in their ability to measure static HR and BP.

Figure.

Blood pressure (BP) and heart rate (HR) screening rates at initial evaluation.

Covariates/factors that influenced screening behavior

To examine which covariates most strongly influenced the likelihood of screening, a univariate ordinal logistic regression was performed (Tab. 4). Following this analysis, it was determined that higher percentages of patients with CVD or at moderate risk were the strongest factor in determining screening rate. Respondents with the highest percentage of at-risk patients screened the most often (100% of caseload; odds ratio [OR] = 19.972; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 6.625–60.211; P <.0001), and the likelihood of screening increased as the percentage of higher-risk patients on the caseload increased. Age, a risk factor for CVD itself, and encountering higher-risk patients at evaluation were also demonstrated to be predictors of BP screening. Those physical therapists completing residency or fellowship programs screened BP more often than those without this training. Holding a clinical doctorate or terminal doctorate, and more years of practice were also significant predictors of BP screening (Tab. 4 and Tab. 5). Possession of a board-certified clinical specialization was not associated with a significant difference in the likelihood of screening (OR = 1.136; 95% CI = 0.962–1.341; P = .1322). To correct for relationships within factors from the univariate analysis, a multivariate ordinal logistic regression was performed (Tab. 5). Two covariates were strongly influenced by this statistical correction. Following univariate analysis, increased age of caseload and individuals who had integrated cardiopulmonary courses—where the cardiopulmonary curriculum is not issued in a stand-alone course but delivered across other courses in physical therapy school—were associated with an increased likelihood of screening (Tab. 4). However, after correcting with multivariate analysis it was found that no significant difference in screening likelihood was observed between either course formats or age of caseload. In contrast, multivariate analysis results showed that clinicians practicing more than 20 years had an increased likelihood of performing BP screening in their practice.

Discussion

Although the BP and HR screening rate had improved compared with previously published studies,18 the overwhelming majority of physical therapists responding to this survey reported that they did not routinely include BP and HR screening at the initial examination. These results are surprising considering that most respondents reported frequently encountering patients with diagnosed CVD or patients classified as having moderate or greater risk for CVD, both in their current caseload and during the evaluation of new patients. A majority of respondents also reported that they were adequately equipped to perform routine screening and were competent at screening.

Despite the overall low screening rate for respondents to this survey, there were several key factors identified in this analysis that were associated with a greater likelihood of screening BP and HR. Physical therapists who completed an accredited postprofessional residency or fellowship program were more likely to perform BP and HR screening than non–residency- or non–fellowship-trained physical therapists. Interestingly, this relationship was not demonstrated to be significant between physical therapists who had specialist certification compared with those without certification. Whereas clinicians practicing for more than 20 years were more likely to perform BP and HR screening, individuals whose highest earned degree was either a master's or bachelor's degree in physical therapy were less likely to screen than individuals with an entry level or transitional doctor of physical therapy degree. These results are interesting, considering that individuals practicing for more than 20 years would have more likely earned a master's or bachelor's degree. Clinical doctorates of physical therapy have only existed since 199221 and became the standard for all professional programs in 2015.22 Those earning postprofessional terminal academic degrees were also more likely to perform screening than those without these degrees.

Additionally, respondents reported a variety of different formats regarding entry-level cardiopulmonary education and the qualifications of their instructor. Univariate regression demonstrated that a full-semester course during entry-level training was associated with a greater likelihood of screening. However, after multivariate regression no significant differences in the likelihood of screening were observed for either course format or qualifications of the instructor. These results suggest that engaging in postprofessional training and structured mentorship as well as a commitment to ongoing education can be beneficial in maintaining a higher standard of practice. Ongoing and structured postprofessional education has been associated with improved clinical outcomes in physical therapist practice.23 Postprofessional residencies or fellowships specifically have been shown to result in improved clinical practice in different health care professions,24–27 including physical therapy.28Another key factor identified in this analysis was the risk profile of the respondents’ caseload. Physical therapists who reported a caseload with patients possessing higher CVD risk profiles were more likely to perform screening than those with lower-risk caseloads, and this relationship was observed both on the initial examination and current caseload. This relationship between higher-risk profile of patients encountered and higher screening rates could also explain why the most commonly reported reason for screening by respondents who screened routinely was perceived importance to the populations they manage. It is reasonable to suggest that clinicians who more frequently encounter patients with CVD or at increased risk for CVD are more likely to be cognizant of the importance of screening and make it a standard component of their clinical examination. Previous studies have suggested that provider perceptions toward disease influence practice behavior,29–31 and the more often someone performs a behavior the more likely it is to become routine.29,32

Although this study demonstrates a significant and substantial disparity between the CVD risk profile of most patients encountered in orthopedic physical therapist practice and the screening rate of clinicians, there appear to be several potential opportunities to address this issue. As stated previously, almost all respondents to this survey reported adequate equipment and competency in performing basic CVD screening such as resting BP and HR. These findings are consistent with the recent findings by Arena et al,33 which demonstrated a similarly low screening rate among outpatient physical therapists despite a high self-reported competency with BP and HR measurement and adequate access to equipment. Additionally, the most commonly reported reasons for not screening were a lack perceived importance, lack of clinic policy, and limited available time. These primary barriers to routine screening result from gaps in knowledge and policy, both of which possess significant liability. Changing perceptions regarding the importance of CVD screening can be addressed through educational and knowledge translation efforts directed toward clinicians and students, which could help to include this screening in clinic policies and standards. Based on the results of this survey, postprofessional residencies or fellowships and structured ongoing education could be tenable solutions. Data suggest that knowledge translation efforts using social media can also be leveraged to improve clinician knowledge and practice patterns.34 Institutional or professional polices can be developed or modified to require screening and to make it more time efficient. Our data demonstrate that such policies regarding BP and HR screening are currently being implemented in some outpatient clinics with success. Furthermore, the development of physical therapy–specific clinical practice guidelines or scientific statements from professional organizations could assist with this process by making the interpretation of BP and HR data easier for clinicians, as well as the decisions regarding when to refer a patient to a different provider. Although a lack of certainty regarding how to use BP and HR measurement was reported by only 5.6% of respondents, we feel that this might potentially be underreported given the low rate of screening.

Limitations

This study provides key insights regarding BP and HR screening behaviors and perspectives toward screening in outpatient orthopedic settings; however, there are some limitations. Although the sampling population was large and representative of the profession, only members of the American Physical Therapy Association Orthopaedic Section were included. Currently, only approximately 30% of licensed physical therapists in the United States are members of the American Physical Therapy Association,35,36 and fewer than 10% are members of the Orthopaedic Section.36,37. Despite the large number of responses, the response rate for the survey was lower than previous studies. However, the present study used an external survey model where responses rates between 10% and 15% would be considered acceptable.19,38–41 Additionally, although the survey did undergo an extensive piloting and development process that involved a representative piloting group similar to previous studies,18 the reliability of the survey was not quantified.

Conclusion

In summary, we found that the screening rate for CVD risk factors by outpatient physical therapists at the initial examination has improved compared with previous studies.18 However, the screening rate remains significantly inadequate in relation to the high rates of CVD risk factors present in the patient population managed by outpatient physical therapists, as demonstrated both in previous studies6,8,9 and the present study. Those who screened routinely most often reported that they perceived it to be important or that their clinic had a screening policy. Those who did not screen routinely reported a perceived lack of importance, lack of clinic policy, or limited time as reasons for not screening. These data are interesting considering that the majority of respondents overall reported frequent encounters with patients at moderate or greater risk for CVD at the initial evaluation on their current caseload; moreover, a lack of available equipment or lack of competency do not appear to be barriers. Multivariate ordinal regression analysis revealed that the likelihood of screening increased as clinicians were exposed to patient caseloads with higher-risk profiles. The analysis also revealed that structured postprofessional training and structured ongoing education were associated with an increased likelihood of screening. The combination of these results indicates that strategies to improve clinician knowledge regarding the importance of CVD screening and the development of clinic policies toward screening could be effective solutions. The results also indicate that postprofessional programs including residencies or fellowships could be effective models for providing education regarding CVD screening to practicing clinicians. As the prevalence of CVD continues to increase while physical therapists assume more direct-access positions in the health care system, this disparity should be addressed. Lack of patient awareness, access to treatment, and effective control of CVD risk factors,42–44 especially HTN,12,13 remain significant issues facing the US health care system, with significant adverse consequences in terms of health care costs, morbidity, and mortality.3,14,15 Early detection of CVD risk factors is important, and physical therapists can play a role in improving the screening rate as members of the allied health care team. Future studies could examine differences in screening rates between practice settings and determine the most effective strategies to address the disparity in the risk profiles of patient populations receiving outpatient orthopedic physical therapy services and CVD risk screening by clinicians. Pragmatic studies could also investigate the most effective measures for early detection and management of CVD risk factors by outpatient physical therapists.

Supplementary Material

Author Contributions

Concept/idea/research design: R. Severin, A. Wielechowski, S.A. Phillips

Writing: R. Severin, E. Wang, S.A. Phillips

Data collection: R. Severin

Data analysis: R. Severin, E. Wang, S.A. Phillips

Project management: R. Severin

Providing participants: R. Severin

Providing facilities/equipment: S.A. Phillips

Clerical/secretarial support: A. Wielechowski

Consultation (including review of manuscript before submitting): A. Wielechowski.

Funding

There are no funders to report for this study.

Disclosures

The authors completed the ICJME Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and reported no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Frese EM, Fick A, Sadowsky HS. Blood pressure measurement guidelines for physical therapists. Cardiopulm Phys Ther J. 2011;22:5–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhang D, Shen X, Qi X. Resting heart rate and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the general population: a meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2016;188:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bromfield S. High blood pressure: The leading global burden of disease risk factor and the need for worldwide prevention programs. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2014;15:134–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS et al.. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2015 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131(4). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Singh G, Miller JD, Lee FH, Pettitt D, Russell MW. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors among US adults with self reported osteoarthritis. Am J Manag Care. 2002;8:383–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Leino-Arjas P, Solovieva S, Kirjonen J, Reunanen A, Riihimäki H. Cardiovascular risk factors and low-back pain in a long-term follow-up of industrial employees. Scand J Work Environ Heal. 2006;32:12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Taylor AJ, Kerry R. Vascular profiling: should manual therapists take blood pressure?. Man Ther. 2013;18:351–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fernandes GS, Valdes AM. Cardiovascular disease and osteoarthritis: common pathways and patient outcomes. Eur J Clin Invest. 2015;45:405–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ranger TA, Wong AMY, Cook JL, Gaida JE. Is there an association between tendinopathy and diabetes mellitus? A systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sport Med. 2016;50:982–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Boissonnault WG. Prevalence of comorbid conditions, surgeries, and medication use in a physical therapy outpatient population: a multicentered study. J Orthop Sport Phys Ther. 1999;29:506–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kessler CS, Joudeh Y. Evaluation and treatment of severe asymptomatic hypertension. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81:470–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Olives C, Myerson R, Mokdad AH, Murray CJL, Lim SS. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in United States counties, 2001-2009. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fryar CD, Ostchega Y, Hales CM, Zhang G, Kruszon-Moran D. Hypertension prevalence and control among adults: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;10:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Engström S, Berne C, Gahnberg L, Svärdsudd K. Efficacy of screening for high blood pressure in dental health care. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Danaei G, Ding EL, Mozaffarian D et al.. The preventable causes of death in the United States: comparative risk assessment of dietary, lifestyle, and metabolic risk factors. PLoS Med. 2009;6: e1000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fleming S, Atherton H, Mccartney D et al.. Self-screening and non-physician screening for hypertension in communities: a systematic review. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28:1316–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Community Preventive Services Task Force (CPSTF). Team-based care to improve blood pressure control: recommedation of the Community Preventive Services Task Force. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47:100–102. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18. Frese EM, Richter RR, Burlis T V. Self-reported measurement of heart rate and blood pressure in 354 patients by physical therapy clinical instructors. Phys Ther. 2002;82:1192–1200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. American Association of Physical Therapy. APTA Guide to Physical Therapist Practice. Phys Ther. 2014;81:9–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Swinkels ICS, Hart DL, Deutscher D et al.. Comparing patient characteristics and treatment processes in patients receiving physical therapy in the United States, Israel, and the Netherlands: cross sectional analyses of data from three clinical databases. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mathur S. Doctorate in physical therapy: Is it time for a conversation? Physiother Canada. 2011;63(2):140–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. American Physical Therapy Association. Strategic plan. http://www.apta.org/strategicplan. 2018. Accessed November 20, 2018.

- 23. Cleland JA, Fritz JM, Brennan GP, Magel J. Does continuing education improve physical therapists’ effectiveness in treating neck pain? A randomized clinical trial. Phys Ther. 2009;89:38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Raub JN, Thurston TM, Fiorvento AD, Mynatt RP, Wilson SS. Implementation and outcomes of a pharmacy residency mentorship program. Am J Heal Pharm. 2015;72:S1–S5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Boissonnault WG, Ross MD. Physical therapists referring patients to physicians: a review of case reports and series. J Orthop Sport Phys Ther. 2012;42:446–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cox M, Irby DM, Cooke M, Sullivan W, Ludmerer KM. Medical education: American medical education 100 years after the Flexner report. N Engl J Med. 2006;13355:1339–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Smith KM, Pharm D, Sorensen T et al.. Value of conducting pharmacy residency training. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30:490–510. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rodeghero J, Wang Y-C, Flynn T, Cleland J, Wainner R, Whitman JM. The impact of physical therapy residency or fellowship education on clinical outcomes for patients with musculoskeletal conditions. J Orthop Sport Phys Ther. 2015;45:86–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Parish SL, Swaine JG, Son E, Luken K. Determinants of cervical cancer screening among women with intellectual disabilities: evidence from medical records. Public Health Rep. 2013;128:519–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cainzos-Achirica M, Blaha MJ.. Cardiovascular risk perception in women: true unawareness or risk miscalculation? BMC Med. 2015;13:2–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mirand AL, Beehler GP, Kuo CL, Mahoney MC. Physician perceptions of primary prevention: qualitative base for the conceptual shaping of a practice intervention tool. BMC Public Health. 2002;2:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McGlothlin H, Killen M.. How social experience is related to children's intergroup attitudes. Soc Psychol Eur. 2010;40:625–634. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Arena SK, Reyes A, Rolf M, Schlagel N, Peterson E. Blood pressure attitudes, practice behaviors, and knowledge of outpatient physical therapists. Cardiopulm Phys Ther J. 2018;29:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tunnecliff J, Weiner J, Gaida JE et al.. Translating evidence to practice in the health professions: a randomized trial of Twitter vs Facebook. J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2016;24(2):403–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. American Physical Therapy Association. APTA 2017 Annual report. http://www.apta.org/uploadedFiles/APTAorg/About_Us/Annual_Reports/APTA_AnnualReport2017.pdf. 2018. Accessed November 20, 2018.

- 36. United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational employment and wages, May 2017: 29-1123 Physical Therapists. Occupational Employment Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291123.htm#ind. 2017. Accessed November 20, 2018.

- 37. Salvatori N. Membership Committee Report APTA Orthopaedic Section. https://www.orthopt.org/uploads/content_files/files/04%20Membership%20Report_CSM%2017.pdf.2017.; Accessed September 24, 2018.

- 38. Ainsworth B. The compendium of physical activities tracking guide. http://prevention.sph.sc.edu/tools/docs/documents_compendium.pdf. 2002. Accessed November 20, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Aiyagari V, Gorelick PB.. Management of blood pressure for acute and recurrent stroke. Stroke. 2009;40:2251–2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kelley K, Clark B, Brown V, Sitzia J. Good practice in the conduct and reporting of survey research. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2003;15:261–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Van Zant RS, Cape KJ, Roach K, Sweeney J. Physical therapists’ perceptions of knowledge and clinical behavior regarding cardiovascular disease prevention. Cardiopulm Phys Ther J. 2013;24:18–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2011-2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2015;219:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Borer JS. Heart rate: from risk marker to risk factor. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2008;10:F2–F6. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Yardley JE et al.. Physical activity/exercise and diabetes: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:2065–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.