Abstract

Background: Persistent angina is prevalent in women, who more often present with atypical angina, and experience less relief from antianginal therapies. The impact of ranolazine on female-specific angina is unclear. A single-arm, open-label trial was conducted to quantify the impact of ranolazine on angina in women with ischemic heart disease (IHD).

Materials and Methods: Women with IHD and ≥2 angina episodes/week were recruited from 30 U.S. sites. Angina and nitroglycerin (NTG) consumption were assessed using patient-reported diaries, Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ), Duke Activity Score Index (DASI), and Women's Ischemia Symptom Questionnaire (WISQ) at baseline and at 4 weeks of treatment with ranolazine 500 mg twice/day. A modified intent-to-treat analysis and parametric or nonparametric methods were used as appropriate to analyze changes.

Results: Of 171 women enrolled, mean age was 65 ± 12 years. Of the 159 women included in the analysis, at week 4 compared to baseline, median angina frequency decreased with ranolazine treatment from 5.0 to 1.5 attacks/week and median change from baseline was −3.3 (95% confidence interval [CI]: −4.0 to −2.5; p ≤ 0.0001). Median NTG consumption decreased from 2.0 to 0.0 per week over the 4 weeks and median change was −1.0 (95% CI: −2.0 to −0.5; p < 0.0001). All five SAQ subscales showed mean improvements: physical limitation 9.2 (standard error [SE] 1.5; p < 0.0001), angina stability 31.8 (SE 2.7; p < 0.0001), angina frequency 17.7 (SE 1.6; p < 0.0001), treatment satisfaction 9.3 (SE 1.6; p < 0.0001), and disease perception 2.9 (SE 0.8; p < 0.0001). DASI score also improved 2.9 (SE 0.8; p = 0.0014). WISQ subscales also showed significant improvements (all p < 0.0001). Thirty-one women reported drug-related adverse events (AEs), predominantly mild to moderate gastrointestinal symptoms.

Conclusions: Women with IHD treated with ranolazine for 4 weeks experienced less angina measured by SAQ and WISQ. NTG use decreased, physical activity improved, and treatment satisfaction improved. AEs were consistent with prior reports.

Keywords: ranolazine, angina, women, and heart disease

Introduction

Persistent angina is a major problem in women with ischemic heart disease (IHD) and is associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes.1–3 The evaluation of angina in women remains a challenge, in part, due to gender-specific differences in angina presentation. The definition of “typical” angina is derived from research with predominantly male cohorts.4 Women often present with symptoms such as dyspnea or throat, neck, or jaw pain rather than the classic exertional chest pain.5 Women with angina also have lower rates of obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) at angiography.4,6,7 Once the source of chest pain is determined to be due to myocardial ischemia, traditional antianginal medications such as beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, and nitrates are usually offered to control anginal symptoms. Women, however, experience less relief from usual antianginal medications and have recurrent presentations to emergency room and physician offices, with adverse economic consequences on our health care system.8

Ranolazine is a late sodium channel blocker approved in 2006 for treatment of chronic stable angina.9 An initial study examined an immediate-release form of ranolazine and showed only short-lived improvements in exercise duration and symptoms of ischemia during exercise.10 Four subsequent major randomized trials of extended release ranolazine on chronic stable angina demonstrated that ranolazine increased exercise duration and time to ST segment depression, decreased angina frequency, and decreased nitroglycerin (NTG) use.11–14

In subgroup analyses of these trials, women showed less improvement than men at exercise testing, raising the question of whether ranolazine was less effective for female-specific anginal symptoms or whether exercise testing was an adequate tool to evaluate ischemia in women. Women did, however, have similar improvements in angina frequency and NTG consumption with ranolazine. Subgroup analyses of these studies are limited because women constituted only ∼20% of the subjects and the distribution of women included in these studies was different from that typically seen in trials of patients with angina.15 In this study, we evaluated the impact of ranolazine on female-specific anginal symptoms using several modalities, including angina frequency, NTG frequency, Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ), Duke Activity Score Index (DASI), and Women's Ischemia Symptom Questionnaire (WISQ). The WISQ is a newly developed questionnaire designed to specifically assess angina symptomatology in women because the SAQ was developed based on predominantly male populations, although subsequently validated in women.16

Materials and Methods

Patient population

Women ≥18 years old were recruited at 30 US sites. Inclusion criteria were as follows (1) at least 3 months of stable angina/angina equivalent relieved by rest and/or sublingual NTG; (2) use of antianginal therapy with beta-blockers, dihydropyridine calcium antagonists, and/or long-acting nitrates for at least 4 weeks and at a dose that has not been adjusted within 2 weeks before screening; (3) mean angina frequency of ≥2 attacks per week; and (4) evidence of ischemia by at least one of the following: (a) positive cardiac imaging stress testing, (b) ST segment depression on exercise treadmill testing (ETT) with prior angiographic evidence of at least 50% stenosis in ≥1 major coronary arteries, or (c) ST segment depression on ETT with a history of myocardial infarction documented by positive biomarkers for myocardial necrosis. Women were included if they had evidence of myocardial ischemia, regardless of their CAD status. There was no core laboratory angiographic determination of CAD status in this multisite study. Decision to revascularize for obstructive CAD was per routine clinical care by treating physician. Subjects in this study were included if they had ischemia and persistent angina, despite catheterization-based treatment for stenosis.

Exclusion criteria included the following: (1) clinically significant hepatic impairment; (2) treatment with strong cytochrome P4503A inhibitors, HIV protease inhibitors, and or consumption of grapefruit juice; (3) prior treatment with ranolazine; (4) participation in another drug/device trial within 30 days of screening; (5) not literate in English; (6) major chronic illness, hepatic impairment, end-stage renal disease; (7) myocardial infarction or unstable angina within 2 months of screening; (8) second or third degree atrio-ventricular block in the absence of a functioning pacemaker; (9) uncontrolled clinically significant cardiac arrhythmia not associated with acute coronary syndrome; (10) QTc >500 mseconds; (11) active acute myocarditis or pericarditis; (12) uncontrolled hypertension (BP ≥160/100 mmHg); (13) hypotension (sitting or supine systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg); and (14) pregnant or breastfeeding. The Institutional Review Board at each site approved the study and all participants gave informed consent.

Study design

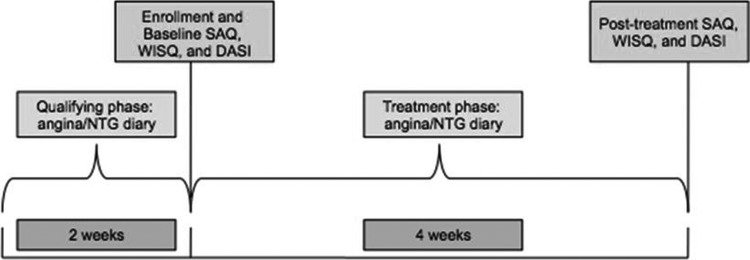

Women potentially eligible for the trial entered a 2-week qualifying phase in which they continued their baseline antianginal medications without changing the dose or frequency and completed diaries recording the occurrence of angina episodes and NTG consumption. They also completed the SAQ, WISQ, and Duke Activity Status Index (DASI) to assess baseline angina symptoms, treatment, and functional status. Women who met all enrollment criteria and had diary documentation of ≥2 angina attacks per week during the qualifying phase entered into the open-label treatment phase. During the 4-week treatment phase, participants were given open-label extended release ranolazine tablets and instructed to take 500 mg twice daily (i.e., lowest FDA recommended dose) Participants continued daily diaries recording angina episodes and NTG consumption. After 4 weeks, participants completed posttreatment SAQ, WISQ, and DASI questionnaires and the remaining ranolazine pills were collected (Fig. 1). Each participant's usual antianginal medication regimen was continued unchanged throughout the study. The class of antianginals used were beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, and nitrates. The electrocardiography (ECG) was obtained at baseline and at study completion. There was no ECG core laboratory in this study. The site investigator inspected the ECG for any clinically significant abnormalities, including QTc interval >500 mseconds. If the QTc internal was >500 mseconds at screening, the subject was considered a screen failure.

FIG. 1.

Study design.

Questionnaires

The SAQ is a 19-item, well-validated, self-administered questionnaire that assesses five aspects of CAD: physical limitation, anginal stability, anginal frequency, treatment satisfaction, and disease perception. Analysis of the questionnaire results in a score ranging from 0 to 100 for each of the five categories where 0 represents most symptomatic and 100 the least symptomatic.17 The WISQ was developed to capture atypical and more female-specific anginal symptoms (Supplementary Data and Appendix 1). It is a 10-item self-administered questionnaire comprising similar five subscales as the SAQ (physical limitation, anginal stability, etc.), but with different scoring. To avoid bias, the WISQ and the SAQ were administered in a counterbalanced order depending on the study subject identification number: WISQ was followed by SAQ for odd subject numbers, and SAQ was followed by WISQ in even subject numbers.

The DASI is a 12-item, self-administered questionnaire, in which subjects answer questions about activities, including personal care, ambulation, household tasks, sexual function, and recreational activities. The questionnaire can be used to obtain a rough estimate of a patient's peak oxygen uptake. Analysis of the questionnaire results in a single score ranging from 0 to 58.2 where the higher the score, the better the individual's functional ability.18

Adverse events

An adverse event (AE) was defined as “Any untoward medical occurrence in a patient or clinical investigation subject administered a pharmaceutical product and that does not necessarily have a causal relationship with this treatment.” AEs were assessed as mild, moderate, or severe (Appendix 2). AEs were collected from the time of subject consent through the protocol-specified follow-up contact (7-day follow-up) as volunteered by the subject or solicited through indirect questioning. The investigator determined whether each AE met criteria for a serious AE. A serious AE was defined as an event resulting in any of the following outcomes: death, life-threatening situation with subject at immediate risk of death, inpatient hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization, significant disability/incapacity, congenital anomaly/birth defect in the offspring of a subject who received study drug, and any medically significant events (based on medical and scientific judgment) that may have jeopardized the subject or may have required medical/surgical intervention.

Statistical analysis

Analyses of efficacy data were performed using a modified intent-to-treat (M-ITT) analysis set defined as all subjects who took at least one dose of the study dose and completed questionnaires at baseline and the end of the study. Analyses of safety data were performed using the analysis set of subjects who received at least one dose of study drug. To measure the effect of ranolazine, the mean and median changes from baseline in angina frequency, NTG use frequency, SAQ score, DASI score, and WISQ score were estimated (point estimate and 95% confidence interval [CI]). Nonparametric techniques were used for angina burden and NTG use (Wilcoxon signed rank test) and parametric methods (Student's t-test) were used for the remaining summaries. No adjustments were made for multiple hypothesis testing and no imputations were performed for missing data.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 172 subjects were enrolled at the 30 U.S. sites. One enrolled subject withdrew from the study before receiving ranolazine treatment. Of the 171 women enrolled, 150 completed the study. Nineteen women did not complete the study, due to an AE (n = 11), elective withdrawal (n = 6), completion status unknown (n = 2), not meeting eligibility requirements (n = 1), and not attending scheduled visits (n = 1). A total of 159 women had a baseline and a week 4 visit who had taken at least one dose of ranolazine. Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. A majority of the women had hypertension, nearly one-third had diabetes, and over one-third had a history of myocardial infarction. At enrollment, ∼28% of patients were on one antianginal class, 58% were on two antianginals, and 10% were on three antianginals. Since “per protocol” population analysis was used, the sample size of 159 was decreased to 141 subjects based on the following: 2 subjects did not have a baseline physical limitation SAQ (PL SAQ) score calculated at baseline or 4 weeks even though they completed the SAQ; 4 subjects had missing baseline PL SAQ, but had a PL SAQ at 4 weeks; 12 subjects had a baseline PL SAQ, but no 4-week values even though they completed a SAQ.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics

| n = 171 | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) (mean ± SD) | 65 ± 12 |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | |

| Asian | 1.8 |

| Black | 11.7 |

| Caucasian | 83.6 |

| Hispanic | 2.9 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 29.5 ± 6.3 |

| History of myocardial infarction (%) | 35.7 |

| Prior percutaneous coronary intervention (%) | 52.6 |

| History of stroke (%) | 7.6 |

| History of congestive heart failure (%) | 16.4 |

| Hypertension (%) | 84.8 |

| Diabetes (%) | 29.8 |

| Aspirin (%) | 76 |

| Beta-blockers (%) | 43 |

| Alpha and beta blockers (%) | 10 |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (%) | 34 |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers (%) | 21 |

| Calcium channel blockers (%) | 17 |

| Nitrates (%) | 47 |

| Statins (%) | 73 |

SD, standard deviation.

Angina burden and NTG use

Median angina frequency following ranolazine treatment decreased from a baseline of 5.0 attacks per week to 1.5 attacks per week at week 4; the median (95% CI) change from baseline was −3.3 [−4.0 to −2.0] (p < 0.0001). NTG use decreased from a baseline median of 2.0 uses per week to 0.0 uses per week at week 4; the median (95% CI) change was −1.0 [−2.0 to −0.5] (p < 0001). Thirty-six out of 159 subjects reported complete resolution of angina and no NTG use.

SAQ, WISQ, and DASI questionnaires

Overall, all five subscales of the SAQ improved with ranolazine (Table 2); all scores were higher at week 4, indicating improved symptoms at week 4 compared to baseline. Mean values for all subscales from the WISQ questionnaire similarly demonstrated an improvement at week 4 compared to baseline. In the WISQ questionnaire, lower scores indicate less symptoms. The DASI increased from a baseline mean of 23.9–26.8 at week 4, a mean (standard error) increase of 2.9 (0.8), which corresponds to an increase of ∼0.3 metabolic equivalent of task (METs) (from 5.7 to 6 METs) and indicates lesser disability.

Table 2.

Change in Seattle Angina Questionnaire and Women's Ischemia Symptom Questionnaire Scores After Ranolazine Treatment

| N | Baseline (mean) | Week 4 (mean) | Change from Baseline to week 4 (mean [SE]) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAQa | |||||

| Physical limitation (0–100) | 141 | 53.0 | 62.2 | 9.2 (1.5) | <0.0001 |

| Angina stability (0–100) | 158 | 38.3 | 70.1 | 31.8 (2.7) | <0.0001 |

| Angina frequency (0–100) | 158 | 45.6 | 63.2 | 17.7 (1.6) | <0.0001 |

| Treatment satisfaction (0–100) | 158 | 73.8 | 83.1 | 9.3 (1.6) | <0.0001 |

| Disease perception (0–100) | 156 | 42.1 | 59.6 | 17.5 (1.7) | <0.0001 |

| WISQb | |||||

| Physical limitation (0–4) | 159 | 1.9 | 1.3 | −0.7 (0.1) | <0.0001 |

| Angina stability (0–8) | 159 | 5.2 | 3.9 | −1.4 (0.2) | <0.0001 |

| Angina frequency (0–75) | 159 | 37.7 | 27.8 | −9.9 (1.1) | <0.0001 |

| Treatment satisfaction (0–5) | 159 | 2.0 | 1.3 | −0.7 (0.1) | <0.0001 |

| Disease perception (0–4) | 159 | 1.5 | 1.1 | −0.4 (0.1) | <0.0001 |

| DASI (0–58.2)c | 159 | 23.9 | 26.8 | 2.9 (0.8) | 0.0014 |

| N | Baseline (median) | Week 4 (median) | Change from baseline to week 4 (median, 95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angina frequency (per week) | 155 | 5.0 | 1.5 | −3.3 (−4.0 to −2.0) | <0.0001 |

| Nitroglycerin use (per week) | 155 | 2.0 | 0.0 | −1.0 (−2.0 to−0.5) | <0.0001 |

A higher SAQ score is better. A lower SAQ score indicates more symptomatic.

A lower WISQ score is better. A higher WISQ score is more symptomatic.

A higher DASI score is better. A lower DASI score indicates more limitation.

DASI, Duke Activity Score Index; SAQ, Seattle Angina Questionnaire; WISQ, Women's Ischemia Symptom Questionnaire.

Adverse events

Of the 171 women treated in this study, 63 (36.8%) reported at least 1 AE, with the most common AE being nausea (Table 3). Thirty-one women in the entire cohort (18%) had an AE that was considered by the investigator to be related to the study drug. No deaths occurred. Treatment-emergent serious AEs were reported in eight women (4.7%), only one of which was considered related to the study drug. Thirteen of 171 subjects (7.6%) discontinued the study drug prematurely because of treatment-emergent AEs.

Table 3.

Number of Subjects Reporting Adverse Events

| Total (N = 171), N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Any AE | 63 (37) |

| Nausea | 22 (13) |

| Dizziness | 10 (6) |

| Headache | 9 (5) |

| Chest pain | 8 (5) |

| Constipation | 6 (4) |

| Diarrhea | 5 (3) |

| Vomiting | 5 (3) |

| Fatigue | 5 (3) |

| Palpitations | 4 (2) |

| Stomach discomfort | 3 (2) |

| Malaise | 3 (2) |

| Peripheral edema | 3 (2) |

| Contusion | 3 (2) |

| Muscle spasms | 3 (2) |

| Dyspnea | 3 (2) |

AE, adverse event.

The serious AE possibly related to the study drug was dizziness. The patient experienced dizziness following the first dose of the study drug and 2 days later, the dizziness became severe with vomiting. The patient also began to experience chest pain and shortness of breath. Workup was unremarkable, ranolazine was discontinued, and she was treated with meclizine as needed. Her symptoms resolved over the next 10 days. The other serious AEs included four patients who experienced chest pain requiring treatment—two patients had unstable angina and underwent percutaneous coronary intervention, one patient had unstable angina and underwent medical management, and one patient had atypical chest pain treated with opioids. In addition, one patient had a urinary tract infection and congestive heart failure exacerbation, one patient had a mechanical fall, and another patient reported concern that her implantable cardioverter–defibrillator (ICD) fired, although subsequent analysis revealed that there had actually been no ICD discharge.

Discussion

This open-label clinical trial, designed to evaluate the impact of ranolazine on ischemic symptoms in women, demonstrated that addition of ranolazine to background antianginal therapy for 4 weeks resulted in significant reduction in angina frequency and NTG use, and improvement in SAQ, WISQ, and DASI scores. The dose of ranolazine used in this study, 500 mg twice daily (BID), is the lowest FDA recommended dose. The side effects reported in this trial were all previously known and consistent with prior reports. Gastrointestinal complaints (i.e., constipation) were common; QTc prolongation, which is a known effect of ranolazine (mean change of 6 mseconds at 1000 mg BID), was not a significant problem at the dose of 500 mg BID used in this study. Acknowledging the problems inherent in an open-label study that tests pharmacotherapy, we report that a short-term duration of ranolazine for 4 weeks is an effective antianginal therapy in women with chronic angina and evidence of myocardial ischemia, regardless of CAD status.

Given the enormous problem of persistent and recurrent angina in women, optimal medical therapy should include the traditional antianginal medications, as well as ranolazine. Clinicians rely on beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, and nitrates as cornerstones of antianginal therapy. Decades of work demonstrates that these traditional agents are effective treatments for angina. However, there is a relatively large group of symptomatic patients in whom these agents are either not adequate for angina control or are not tolerated due to their hemodynamic effects. As a minimally hemodynamic active add-on therapy to traditional antianginal medications (calcium channel blockers, beta-blockers, and nitrates), ranolazine is an effective antianginal and can be particularly helpful in symptomatic women with low blood pressures in whom calcium channel blockers, beta-blockers, or nitrates cannot be used or titrated to control angina.

This study is consistent with the results from previous trials on the efficacy of ranolazine as an antianginal. In the Monotherapy Assessment of Ranolazine in Stable Angina (MARISA) and Combination Assessment of Ranolazine in Stable Angina (CARISA) trials, ranolazine resulted in improved exercise duration, time to the onset of angina, and time to 1 mm ST-segment depression.11,12 In addition, the CARISA trial showed decreased angina frequency from 3.3 to 2.5 attacks per week and similar decrease in NTG consumption in those treated with ranolazine 750 mg BID versus placebo for 12 weeks.12 The Efficacy of Ranolazine in Chronic Angina (ERICA) trial showed a decrease from 5.6 to 2.9 in self-reported anginal episodes per week, decrease from 4.4 to 2.0 in NTG consumption per week, and a 22.5 point increase in SAQ angina frequency score in subjects treated with ranolazine 1000 mg BID versus placebo for 6 weeks.13 Finally, the Type 2 Diabetes Evaluation of Ranolazine in Subjects With Chronic Stable Angina (TERISA) study showed the a decrease in angina from 6.6 to 3.8 episodes per week and decrease in NTG use from 4.1 to 1.7 times per week in patients with diabetes on ranolazine 1000 mg BID versus placebo for 8 weeks.14 The magnitude of benefit of ranolazine is slightly greater in our study than the aforementioned studies likely due to the open-label nature of this trial. Despite its open-label nature, this study adds to the existing literature by showing that women, who were significantly underrepresented in the prior ranolazine trials and experience less relief from usual antianginal medications, have improvement in anginal symptoms with ranolazine.

Subjects in this study had myocardial ischemia from either obstructive or no obstructive CAD. Women are more likely to have no obstructive CAD in the setting of acute coronary syndromes and in stable IHD compared with men.6,19 In the setting of ischemia and no obstructive CAD, coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD) has been implicated and is believed to play a more important role in women. Subjects enrolled in this study who had no obstructive CAD may have had CMD, but this was not definitely diagnosed by documentation of low coronary flow reserve. Previous randomized trials conducted specifically in women with angina and no obstructive CAD have evaluated the impact of ranolazine and shown mixed results. In a randomized, cross-over pilot study of 20 women with CMD (95% with typical angina at baseline), treatment with ranolazine for 4 weeks resulted in significant improvements in three of five SAQ subscales, with a signal for possible improvement in myocardial ischemia detected by cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging.20 In a subsequent larger cross over trial of ranolazine (RWISE) predominantly in women with no obstructive CAD and CMD (31% with typical angina at baseline), there was no improvement in the SAQ or ischemia (detected by CMR) with 2 weeks of ranolazine treatment.21 However, in RWISE, the subgroup of CMD subjects with a low coronary flow reserve <2.5 had an improvement in angina and myocardial perfusion reserve index on ranolazine compared to placebo. Most recently, in a smaller study of seven patients, treatment with ranolazine showed improvement in the index of microcirculatory resistance, a novel invasive tool for the specific assessment of microcirculation, in women with angina and CMD.22 Finally, in symptomatic diabetic patients without obstructive CAD, ranolazine resulted in improvement in diastolic function but no change in exercise myocardial blood flow or coronary flow reserve.23 While changes in ischemic burden were not quantified and coronary blood flow reserve was not assessed in this open-label study, evidence thus far indicates that ranolazine may be helpful in a subgroup of patients with angina who have significant CMD, a common problem in women.

Limitation

This was an open-label study, and therefore, the placebo effect cannot be excluded.

When patients enroll in clinical trials, solely by the fact that they are enrolled in a trial, they may report improvement as they fill out questionnaires. The quantification of ischemia to correlate changes in symptoms with ischemic burden was not assessed in this study. CAD status was not systematically analyzed in this study by an angiographic core laboratory, and women with and without obstructive CAD were included. Invasive functional angiogram or cardiac positron emission tomography to detect abnormal coronary flow reserve was not evaluated in this study. Thus, we do not know how many of these subjects had CMD. Specific medication changes for other antianginals were not tracked, and no pharmacokinetic endpoints were assessed in this study. Objective measure of improvement in physical function with tracking steps via pedometer/accelerometer or exercise diary was not done.

Conclusion

Women with IHD treated with ranolazine for 4 weeks experienced less anginal symptoms measured by both SAQ and female-specific WISQ angina questionnaire. NTG use decreased, physical activity improved, and treatment satisfaction improved. AEs were consistent with previous reports.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

PI and Institutions are Richard Ansinelli and Robert Touchon, King's Daughter Medical Center, Ashland, KY; Nizar Assi, Gateway Cardiology, PC; St. Louis, MO and Jerseyville, IL; C. Noel Bailey Merz, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA; Vera Bittner, The University of Alabama Birmingham, Birmingham, AL; Rita Coram, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY; Ira Dauber, South Denver Cardiology Associates, PC, Littleton, CO; Ashwini Davuluri, Jacksonville Heart Center, Jacksonville, FL; John Detwiler, Escondido Cardiology Associates, Escondido, CA; Yaron Elad, Access Clinical Trials/Cardiovascular Research Institute (ACT/CVRI), Beverly Hills, CA; Angel Flores, Tri-State Medical Group, Cardiology, Beaver, PA; Garo Garibian, Cardiology Consultants of Philadelphia, Philadelpia, PA; Harinder Gogia, Cardiology Consultants of Orange County, Anaheim, CA; Nieca Goldberg, Total Health Care, New York, NY; Oscar Guerra, Greater Metabolic Associates, Coral Gables, FL; Peter Hanley, Northern Indiana Research Alliance, Fort Wayne, IN; David Hassel, Jacksonville Heart Center, Jacksonville, FL; Ameer Kabour, Toledo Cardiology Consultant's, Cardiac Research, Toledo, OH; Dean Kereiakes, The Lindner Clinical Trial Center, Cincinnati, OH; Michael Koren, Jacksonville Center for Clinical Research, Jacksonville, FL; Steven Krueger, Integrated Cardiology Consultants, LLC d/b/a Bryan LGH Heart Institute, Lincoln, NE; Pamela Rama, Jacksonville Heart Center, Jacksonville, FL; Peter Roan, Mercy Physician Group Cardiology, Nampa, ID; William Short, St. Luke Cardiology Associates, Jacksonville, FL; Brian Shortal, North Shore Cardiology, Bannockburn, IL; M. Thames, Cardiovascular Consultants Ltd, Phoenix, AZ; Gregory Thomas, Mission Internal Medical Group, Mission Viejo, CA; William Tinker, Bluestem Cardiology, Bartlesville, OK; Nanette Wenger, Emory University & Grady Health System, Atlanta, GA; David Wolinsky, Albany Associates in Cardiology, Albany, NY. Funding: This work was supported by contracts from CV Therapeutics/Gilead, the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institutes nos. N01-HV-68161, N01-HV-68162, N01-HV-68163, N01-HV-68164, grants U0164829, U01 HL649141, U01 HL649241, K23HL105787, R01 HL090957, 1R03AG032631 from the National Institute on Aging, GCRC grant MO1-RR00425 from the National Center for Research Resources, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Grant UL1TR000124, and grants from the Gustavus and Louis Pfeiffer Research Foundation, Danville, NJ, The Women's Guild of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, The Ladies Hospital Aid Society of Western Pennsylvania, Pittsburgh, PA, and QMED, Inc., Laurence Harbor, NJ, the Edythe L. Broad and the Constance Austin Women's Heart Research Fellowships, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, the Barbra Streisand Women's Cardiovascular Research and Education Program, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, The Society for Women's Health Research (SWHR), Washington, DC, The Linda Joy Pollin Women's Heart Health Program, and the Erika Glazer Women's Heart Health Project, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA.

Appendix A1. Woman's Ischemia Symptom Questionnaire

Please answer the following questions about your angina over the past 4 weeks. By angina, we mean symptoms that may feel like chest pain, or an unpleasant pressure, tightness, heaviness, or shortness of breath. You may also experience discomfort in your arm, shoulder, or jaw.

Please read each question carefully and choose the best single answer for you. There are no wrong or right answers.

-

1.

Thinking about the past 4 weeks, about how often have you had angina?

□ Never

□ Less than once a week

□ 1–2 times per week

□ 3–6 times per week

□ Once a day

□ More than once a day

-

2.

How severe were your worst angina symptoms over the past 4 weeks? Place a mark on the line below to indicate how severe your worst angina symptoms were on a scale from 0 to 10.

| No angina symptoms at all | 0 | 10 | Worst angina symptoms imaginable | |

These next questions are about activities that you might do in a typical day, such as gardening, preparing a meal, taking care of children, running errands, driving a car, working, going to a movie, or doing housework.

-

3.

Over the last 4 weeks, how much have you felt limited in what you would like to do because of angina?

□ Extremely limited

□ Quite a bit limited

□ Moderately limited

□ Slightly limited

□ Not at all limited

-

4.

Over the last 4 weeks, have you decreased your daily activity due to your angina?

□ Yes (go to 4a.)

□ No (skip to 5.)

-

4a.

If Yes, how much have you decreased your daily activities due to your angina?

□ I have decreased my activities a great deal

□ I have decreased my activities quite a bit

□ I have decreased my activities somewhat

□ I have decreased my activities a little bit

-

5.

Thinking about the past 4 weeks, how much of the time did you feel angina when you did each of the following activities. If you didn't do the activity, please check the appropriate column.

| Over thepast 4 weeks, how much did you feel angina when you… | Always | Often | Sometimes | Rarely | Never | I didn't do this activity because of my angina | I didn't do this activity for other reasons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. Carried in the groceries | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| b. Walked at a slow pace (for example outside or while shopping) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| c. Were outside on a very cold day for 10 minutes or more | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| d. Watched an exciting movie or sporting event | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| e. Were outside on a hot and humid day for 10 | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| f. Cared for children or grandchildren | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| g. Climbed one flight of stairs | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| h. Worked with your hands above your head (for example shampooing hair, changing a light bulb) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| i. Had sex | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| j. were at work (part-time or full-time) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| k. Did mild to moderate exercise (for example walking, swimming) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| l. Ran or jogged | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

| m. Stood in place for 5 minutes or longer (e.g., waiting in line) | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ | □ |

-

6.

Over the past 4 weeks, when you were feeling stressed about something, how much of the time did you feel angina?

Always Often Sometimes Rarely Never I didn't feel stressed

□ □ □ □ □ □

-

7.

Over the past 4 weeks, when you were feeling angry, how much of the time did you feel angina?

Always Often Sometimes Rarely Never I didn't feel angry

□ □ □ □ □ □

-

8.

Have you increased any of your daily activities over the past 4 weeks due to a lessening of your angina?

□ Yes (go to 8a.)

□ No (skip to 9.)

-

8a.

If Yes, how much have you increased your daily activities?

□ I have increased my activities a great deal

□ I have increased my activities quite a bit

□ I have increased my activities somewhat

□ I have increased my activities a little bit

-

9.

Over the last 4 weeks, have you taken nitroglycerin for your angina?

□ Yes (go to 9a.)

□ No

-

9a.

If Yes, how often have you taken nitroglycerin?

□ Less than once a week

□ 1–2 times per week

□ 3–6 times per week

□ Once a day

□ More than once a day

-

10.

Please check the boxes with the words that best describe your angina over the past 4 weeks. If needed, check more than one box.

□ Chest pain □ Fatigue

□ Pressure □ Dizziness

□ Burning □ Sweating

□ Squeezing □ Jaw discomfort

□ Shortness of breath □ Arm discomfort

□ Tightness □ Shoulder discomfort

□ Heaviness □ Back pain

□ Palpitations/rapid heart rate □ Headache

□ Abdominal/stomach pain □ Nausea

-

10a.

Please write down any other words that describe your angina over the past 4 weeks

The following is the scoring algorithm for the WISQ. In general, the higher the score, the worse the symptoms of angina or their impact on the subject's life. For unanswered items, or for item 5 answers, “I didn't do this activity for other reasons”, do not add any value to the score; the scores on these missing items will be imputed. To impute the score for a missing item, substitute the mean of the nonmissing, scored items in the same subscale. If no items are present for a given subscale, substitute the mean of the scores on all present items on the instrument.

The subscales are:

Physical Limitation (range 0–4) item 3

Anginal Stability (range 0–8) items 4, 8

Anginal Frequency/Severity (range 0–75) items 1, 2, 5, 6, 7

Treatment (range 0–5) item 9

Disease Perception (range (0–4) item 10

Item:

-

1.

0 (Never)–5 (More than once a day)

-

2.

0 (No symptoms)–10 (Worst symptoms) NOTE: Use the closest integer value.

-

3.

0 (Not at all limited)–4 (Extremely limited)

-

4.

Score if NO: 0

Score if YES (using 4a): 1 (A little bit)–4 (A great deal)

-

5.

For each of the 13 items, score 0 (Never)–4 (Always or “I didn't do this activity because of my angina.”)

-

6.

0 (Never)–4 (Always)

-

7.

0 (Never)–4 (Always)

-

8.

Score if NO: 4

Score if YES (using 8a): 0 (A great deal)–3 (A little bit)

-

9.

Score if NO: 0

Score if YES (using 9a): 1 (Less than once a week)–5 (More than once a day)

-

10.

Count 1 point for each box checked (score range: 0–20). Multiply the count by 4/20 and round to the nearest integer.

-

11.

Do not score any values for 10(a); these are intended for future research

Appendix A2. Guideline for Assessing Adverse Event Severity

Mild: Awareness of signs or symptoms, but easily tolerated; are of minor irritant type; no loss of time from normal activities; symptoms would generally not require medication or a medical evaluation; signs and symptoms may be transient and disappearing during continued treatment with study medication.

Moderate: Discomfort enough to cause interference with usual activities; signs and symptoms may be persistent or require medical evaluation; the study drug may be interrupted.

Severe: Incapacitating with inability to do work or do usual activities; signs and symptoms may be of systemic nature or require medical evaluation; the study drug may be stopped, and treatment for the event may be required.

Author Disclosure Statement

P.K.M., research support: Gilead; M.M., contracted by Gilead; M.R.H., contracted by Gilead; M.M., research support: NINR, AHA, American Nurses Foundation and honorarium from North American Center for CME; J.A.N., none; L.J.S., none; C.N.B.M., consulting revenue paid to Cedars-Sinai from Gilead, Medscape, Research Triangle Institute, research money from Gilead, Erika Glazer, payments for lectures from Beaumont Hospital, European Horizon, Florida Hospital, INOVA, Korean Cardiology Society, Practice Point Communications, Pri-Med, University of Chicago, VBWG, University of Colorado, University of Utah, WomenHeart, Harold Buchwald Heart-Health, Tufts; N.K.W., consulting and research support: Gilead Sciences. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00644332.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Olson MB, Kelsey SF, Matthews K, et al. Symptoms, myocardial ischaemia and quality of life in women: Results from the NHLBI-sponsored wise study. Eur Heart J 2003;24:1506–1514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Johnson BD, Shaw LJ, Pepine CJ, et al. Persistent chest pain predicts cardiovascular events in women without obstructive coronary artery disease: Results from the NIH-NHLBI-sponsored Women's Ischaemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study. Eur Heart J 2006;27:1408–1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2012;125:e2–e220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shaw LJ, Bairey Merz CN, Pepine CJ, et al. Insights from the NHLBI-Sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) Study: Part I: Gender differences in traditional and novel risk factors, symptom evaluation, and gender-optimized diagnostic strategies. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:S4–S20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Philpott S, Boynton PM, Feder G, Hemingway H. Gender differences in descriptions of angina symptoms and health problems immediately prior to angiography: The ACRE study. Appropriateness of coronary revascularisation study. Soc Sci Med 2001;52:1565–1575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bugiardini R, Bairey Merz CN. Angina with “normal” coronary arteries: A changing philosophy. JAMA 2005;293:477–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pepine CJ, Ferdinand KC, Shaw LJ, et al. Emergence of nonobstructive coronary artery disease: A woman's problem and need for change in definition on angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:1918–1933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shaw LJ, Merz CN, Pepine CJ, et al. The economic burden of angina in women with suspected ischemic heart disease: Results from the National Institutes of Health—National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute—Sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation. Circulation 2006;114:894–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nash DT, Nash SD. Ranolazine for chronic stable angina. Lancet 2008;372:1335–1341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pepine CJ, Wolff AA. A controlled trial with a novel anti-ischemic agent, ranolazine, in chronic stable angina pectoris that is responsive to conventional antianginal agents. Ranolazine Study Group. Am J Cardiol 1999;84:46–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chaitman BR, Skettino SL, Parker JO, et al. Anti-ischemic effects and long-term survival during ranolazine monotherapy in patients with chronic severe angina. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:1375–1382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chaitman BR, Pepine CJ, Parker JO, et al. Effects of ranolazine with atenolol, amlodipine, or diltiazem on exercise tolerance and angina frequency in patients with severe chronic angina: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;291:309–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stone PH, Gratsiansky NA, Blokhin A, Huang IZ, Meng L, Investigators E. Antianginal efficacy of ranolazine when added to treatment with amlodipine: The ERICA (Efficacy of Ranolazine in Chronic Angina) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:566–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kosiborod M, Arnold SV, Spertus JA, et al. Evaluation of ranolazine in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic stable angina: Results from the TERISA randomized clinical trial (Type 2 Diabetes Evaluation of Ranolazine in Subjects with Chronic Stable Angina). J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:2038–2045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wenger NK, Chaitman B, Vetrovec GW. Gender comparison of efficacy and safety of ranolazine for chronic angina pectoris in four randomized clinical trials. Am J Cardiol 2007;99:11–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kimble LP, Dunbar SB, Weintraub WS, et al. The Seattle Angina Questionnaire: Reliability and validity in women with chronic stable angina. Heart Dis 2002;4:206–211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Spertus JA, Winder JA, Dewhurst TA, et al. Development and evaluation of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire: A new functional status measure for coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995;25:333–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hlatky MA, Boineau RE, Higginbotham MB, et al. A brief self-administered questionnaire to determine functional capacity (the Duke Activity Status Index). Am J Cardiol 1989;64:651–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bairey Merz CN. Women and ischemic heart disease paradox and pathophysiology. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2011;4:74–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mehta PK, Goykhman P, Thomson LE, et al. Ranolazine improves angina in women with evidence of myocardial ischemia but no obstructive coronary artery disease. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2011;4:514–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bairey Merz CN, Handberg EM, Shufelt CL, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of late na current inhibition (ranolazine) in coronary microvascular dysfunction (cmd): Impact on angina and myocardial perfusion reserve. Eur Heart J 2016;37:1504–1513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ahmed B, Mondragon J, Sheldon M, Clegg S. Impact of ranolazine on coronary microvascular dysfunction (micro) study. Cardiovasc Revasc Med 2017;18:431–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shah NR, Cheezum MK, Veeranna V, et al. Ranolazine in symptomatic diabetic patients without obstructive coronary artery disease: Impact on microvascular and diastolic function. J Am Heart Association 2017;6 pii: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.