Abstract

Povidone‐iodine is known for successfully treating surgical wounds; the combination between povidone‐iodine and sugar, also called Knutson's formula, has been proposed to improve wound healing. Currently, no studies have investigated the effects of Knutson's formula to treat defects in wound closure following radio‐chemotherapy in the head and neck region. The aim of this study is to evaluate the efficacy of Knutson's formula in improving the wound‐healing process in patients who underwent radio‐chemotherapy after surgery for head and neck cancer. The study, conducted from August 2013 to January 2017, included a sample of 34 patients (25 males and 9 females; age range: 60‐75 years) treated with radio‐chemotherapy after head and neck cancer surgery. All patients suffered from defect of wound regeneration. Patients were randomly divided into two groups: patients in the study group (n = 18) were treated with Knutson's formula; patients in the control group (n = 16) were treated with traditional topical drugs. In the study group, 16 of 18 (88.9%) patients reached complete wound closure 1 month after treatment, with no wound infections. In the control group, only three patients (18.7%) showed complete wound closure within a month; in addition, one patient required systemic antibiotic treatment because of supra‐bacterial infection of the wound. In our sample, the combination of povidone‐iodine and sugar had a higher success rate compared with traditional topical treatment in the treatment of wound defect closure in oncological patients who underwent radio‐chemotherapy.

Keywords: chemotherapy, Knutson's formula, radiotherapy, wound dehiscence, wound healing

1. INTRODUCTION

Povidone‐iodine solution has been widely used as an antimicrobial agent since 1956 due to its ability to contrast bacterial growth, particularly by killing Staphylococcus aureus, Mycobacterium Chelonae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas Cepacia, and Streptococcus mitis.1, 2, 3, 4 The solution has been used for many decades as a topical agent to treat infected wound dehiscence in the head and neck region.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11

Sugar is able to favour healing of skin wounds.12, 13, 14, 15 The use of crystallised sugar is rationally supported by its capacity to increase osmotic concentration and to recall lymphocytes and macrophages in the wound area15; this effect increases the immunity answer and reduces the risk of infection. In addition, sugar is an excellent culture medium for fibroblast growth16, 17, 18 to ameliorate and accelerate the wound‐healing process. Sugar, like honey, has other properties that help the healing process, such as the capacity to reduce oedema and accelerate the removing of necrotic tissue. Furthermore, sugar provides a local source of energy for cells, creates a protective layer over the wound, and increases the granulation process necessary for wound healing.19

In 1981, Knutson et al successfully treated 605 patients affected by wounds, burns, and ulcers using a combination of povidone‐iodine and crystallised sugar, also called Knutson's formula.20 Afterwards, the topical application of a mixture of povidone‐iodine and sugar has been reported to accelerate the healing of cutaneous wounds and ulcers by promoting reepithelialisation and granulation tissue formation, as well as having an antimicrobial effect.21, 22

There is a lack of evidence on the use of povidone‐iodine and sugar for the treatment of head and neck surgical wounds. This study aims to evaluate the effect of Knutson's formula on post‐oncological surgical wound dehiscence following radio‐chemotherapy compared with traditional topical treatment.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted a case‐control study in the Department of Otolaryngology of a tertiary referral centre between August 2013 and January 2017. The study was approved by the hospital institutional review board and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients signed a written informed consent.

The study included patients who underwent surgery for head and neck cancer affected by wound dehiscence because of radio‐chemotherapy performed after cancer removal and not previously treated for the same condition. The following patients were excluded from the study: subjects with autoimmune diseases, with coagulation deficits, who suffered from haemopoietic disorders and were under treatment with anticoagulant drugs and subjects previously treated with any other topical treatment for wound healing.

For each patient we collected the following details: the localisation of the dehiscence (neck, chin, or oro‐cutaneous fistula), the size, the depth, the characteristics of exudate (quantity and quality), the condition of the surrounding tissues, the smell, and the presence of pain.

Table 1 illustrates the characteristics of the exudate that was collected; Table 2 describes the methods that were used to evaluate the surrounding tissues following the Lazarus guidelines.23

Table 1.

Characteristics of the wound exudate

| Quality of exudate |

|---|

| Clear |

| Pink |

| Pink/red |

| Red |

| Yellow |

| Brown |

| Black |

| Thin |

| Thick |

| Viscous |

Table 2.

Method used to evaluate the condition of the wound and of the surrounding tissues

| None | Mild | Severe | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peri‐wound oedema | |||

| Peri‐wound erythema | |||

| Wound granulation | |||

| Wound purulence | |||

| Wound fibrina | |||

| Wound rubor | |||

| Wound calor |

The wound condition was evaluated before treatment (T0) and after 3 (T1), 7 (T2), 10 (T3), 15 (T4), and 30 (T5) days of treatment and classified as follow:

wound with normal quantity (proportional to the stage) and clear exudate with active granulation process and reduced deepness and/or size from the previous check‐up.

wound with excess of exudate or reduced exudate from previous control but without granulation tissue.

wound with infected exudate and increased deepness.

absence of variation from previous control.

Patients were randomly divided into two groups using a simple randomisation method. Patients in the study group were treated with povidone‐iodine and sugar solution; patients in the control group were treated with an antibacterial topical medication. Povidone‐iodine and sugar solution was prepared as follows: 20 parts of sugar, 5 parts of povidone‐iodine in ointment form (10% free iodine), and 2 parts of povidone‐iodine in solution form (10% free iodine). Antibacterial topical medication included rifampicin for local use, connectivine, collagens, and polyurethane foams.

The wound medication was carried out by modifying the standard protocol of treatment and by dividing the procedure into three phases for better checking of the healing process. The treatment was performed for 15 consecutive days in both groups; if requested, because of the persistence of wound dehiscence, treatment was prolonged for up to 30 days.

In the study group, the wound was cleaned with a curette (phase I) and washed accurately, including the surrounding area, with saline (phase II); then, Knutson's formula was applied to the area in a single layer, and the dehiscence was covered with a transpiring sterile gauze (phase III). The treatment was performed with the same modalities every 72 hours.

In the control group, the wound was cleaned with a curette (phase I), washed with Dakin's solution (phase II) followed by the application of rifampicin (used only in this group) and, after a few minutes, connectivine or collagen, and polyurethane foams (phase III). The wound was covered with transpiring sterile gauze. The medication was performed with the same modalities every 72 hours.

Dakin's solution was prepared with chlorine at 1% and physiological isotonic solution. Routine blood tests were performed daily in all patients to monitor the possibility of a systemic infection.

2.1. Statistical analysis

The Kruskal Wallis (KW) test was performed to evaluate statistically significant difference between groups A and B in term of wound healing (1,2,3 and 4) at T1, T2, T3, T4, and T5; ad‐hoc Conover (Con) tests were performed. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patients’ characteristics

Thirty‐four subjects (25 males and 9 females) aged between 60 and 75 years were included in the study. Eighteen patients were included in the study group (13 males and 5 females) and 16 in the control group (12 males and 4 females). Table 3 describes the demographic characteristics of our sample.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the study sample

| Number of patients | Gender | Age range (yr) | Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 6 males, 1 female | 60 to 75 | Squamous cell carcinoma of the floor of the mouth |

| 4 | All males | 64 to 75 | Squamous cell carcinoma of the tonsil |

| 5 | 3 males and 2 females | 62 to 75 | Squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue |

| 2 | 1 male and 1 female | 65 to 71 | Squamous cell carcinoma of the glossoepiglottic vallecula |

| 5 | 4 male and 2 females | 65 to 70 | Squamous cell carcinoma of the gingival fornix |

| 7 | 6 males and 1 females | 60 to 64 | Squamous cell carcinoma of the soft palate |

| 2 | All females | 70 to 74 | Squamous cell carcinoma of the superion gingival mucousa |

| 2 | Male | 70 to 75 | Squamous cell carcinoma of the retromolar trigone |

All patients included in the sample underwent surgical removal of head and neck cancer and reconstruction with free re‐vascularised flap.

Twenty‐four patients (70.6%) had latero‐cervical wound dehiscence, seven (20.6%) had a wound dehiscence in the chin area, and three (8.8%) had an oral‐cutaneous fistula. All wounds presented regular margins, and none of the patients had necrosis in the area. Details on the distribution of patients between the two groups are reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

Wound localisation and size in the study and control groups

| Patient | Location | Size (cm) | Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Latero‐cervical | 8 | Study group |

| 2 | Chin | 3 | Control group |

| 3 | Latero‐cervical | 7 | Control group |

| 4 | Chin | 3.5 | Study group |

| 5 | Oral‐cutaneous fistula | 2 | Study group |

| 6 | Latero‐cervical | 6 | Control group |

| 7 | Latero‐cervical | 7.5 | Study group |

| 8 | Chin | 3 | Study group |

| 9 | Latero‐cervical | 6 | Control group |

| 10 | Chin | 2.5 | Control group |

| 11 | Latero‐cervical | 5 | Study group |

| 12 | Oral‐cutaneous fistula | 1.5 | Control group |

| 13 | Latero‐cervical | 6.5 | Control group |

| 14 | Latero‐cervical | 8 | Control group |

| 15 | Oral‐cutaneous fistula | 1.5 | Study group |

| 16 | Latero‐cervical | 6 | Study group |

| 17 | Chin | 1.5 | Control group |

| 18 | Latero‐cervical | 5 | Study group |

| 19 | Latero‐cervical | 4.5 | Control group |

| 20 | Chin | 3 | Study group |

| 21 | Latero‐cervical | 2.5 | Control group |

| 22 | Latero‐cervical | 4 | Study group |

| 23 | Latero‐cervical | 7 | Study group |

| 24 | Latero‐cervical | 8 | Control group |

| 25 | Latero‐cervical | 5 | Study group |

| 26 | Latero‐cervical | 3.5 | Control group |

| 27 | Chin | 2 | Study group |

| 28 | Latero‐cervical | 6 | Control group |

| 29 | Latero‐cervical | 8 | Study group |

| 30 | Latero‐cervical | 8 | Control group |

| 31 | Latero‐cervical | 5 | Study group |

| 32 | Latero‐cervical | 3 | Study group |

| 33 | Latero‐cervical | 2.5 | Control group |

| 34 | Latero‐cervical | 2 | Study group |

None of the patients was alcohol or drug addicted. All patients were in the normal weight range. Patients with well‐balanced diabetes and hypertension were equally distributed in the study and control groups.

3.2. Study group

All patients in the study group were bacterial infection free during the 15 days of the treatment. None of the patients in this group required an extension of the therapy. One patient died before the end of the therapeutic protocol. No significant differences in the outcomes were observed between males and females.

Twelve patients presented latero‐cervical dehiscence with an average size of 5.45 cm (SD:1.92; CI 95%: 2‐8); four had a chin wound dehiscence (average size: 2.8 cm; SD: 0.6; CI 95%: 2‐3.5), and two suffered from an oral‐cutaneous fistula (average size: 1.75 cm; SD: 0.3; CI 95%: 1.5‐2).

T1: All wounds, independent from their original size and shape, showed absence of exudate, rich granulation tissue, and a decrease in deepness (type 1). None of the patients referred pain in the wound area (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Aspect of the surgical wound at T1, T2, T3, T4, and T5 in a patient treated with povidone‐iodine and sugar solution

T2: In the totality of cases, wounds cavities were almost filled with regenerative pink‐like tissue (type 1).

T3: Signs of active reepithelialisation in the external edge of the wound that converged versus the central area (type A) were evident in all cases (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A summary of the improvement in wound dehiscence healing at the different time points between patients in study and control groups. Asterisks indicate statistical significance

T4: The wounds were completely closed in 16 patients (88.9%); two cases (11.1%) required a skin graft to achieve complete wound closure even if the wound size was significantly reduced (type 1).

T5: All patients presented normal scars (linear wound healing) without hypertrophy or keloid formation, and no wound contractures were observed. The skin over the area previously experiencing wound dehiscence presented a pink hypercromia typical of normal healing process.

No significant differences in wound resolution related to the size or the localisation of the dehiscence were observed.

3.3. Control group

All patients in this group needed an extension of topical treatment for 15 additional days (30 days total) because of the persistence of wound dehiscence. Three patients presented an important over‐infection on the wound site with an increase of white cells and C‐reactive protein. No significant differences in treatment results were observed between males and females.

Twelve patients were affected by latero‐cervical wound dehiscence of an average size of 5.7 cm (SD: 2; CI 95%: 2.5‐8), three presented a chin dehiscence (average size: 2.3 cm; SD: 0.7; CI 95%:1.5‐3), and one had an oral‐cutaneous fistula (size: 1.5 cm).

T1: No variations in wounds characteristics from T0 were observed in all patients (type 4).

T2: We observed the presence of abundant exudate and absence of regenerative tissue matrix, without bacterial infection (type 2). All patients referred pain in the wound area.

T3: In three patients (18.7%), the wound presented a bacterial infection associated with bad smell (type 3). Two patients (12.5%) presented an important hyperaemia of skin surrounding the wound cavity, suggesting tissue sufferance for excessive inflammatory reaction (type 3). A reduction of exudate in the wound area was observed in 11 patients (68.7%) without change in deepness of the lesion (type 2).

T4: We observed, in 13 cases (81.2%), a dry wound with granulation tissue but without active signs of the reepithelialisation process (pink‐like regenerative tissue) (type 2). Three patients needed systemic antibiotic treatment to fight the increase of bacterial growth and the persistence of the infection in the wound area.

T5: Despite the extension of therapy, complete wound healing (as primary intention) was seen in only three patients, while the others had secondary‐intention wound healing.

3.4. Statistical comparison

We identified statistically significant results by comparing the two treatments at T1 (Con: P < 0.0001), T2 (Con: P < 0.0001), T3 (Con: P = 0.04), T4 (Con: P < 0.0001), and T5 (Con: P < 0.001) .

4. DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study on the use of povidone‐iodine and sugar solution‐Knutson' formula‐ for the treatment of surgical skin dehiscence following radio‐chemotherapy in the head and neck region. Our data suggest that a mixture of povidone‐iodine and sugar may be a valid alternative to the standard topical treatment of post‐surgical wound dehiscence following radio‐chemotherapy in the head and neck region.

The management of skin wound dehiscence in patients who underwent radio‐chemotherapy is extremely complex because of the toxic effect that these treatments have on tissues. Both treatments reduce the regenerative capacity of skin: chemotherapy increase the oxidative stress that poisons the skin fibroblasts by reducing their ability to rebuild a normal cellular matrix; radiotherapy, by increasing the temperature in the area in which is performed, causes the death of the fibroblasts, with a consequent reduced ability in performing correct wound healing.24

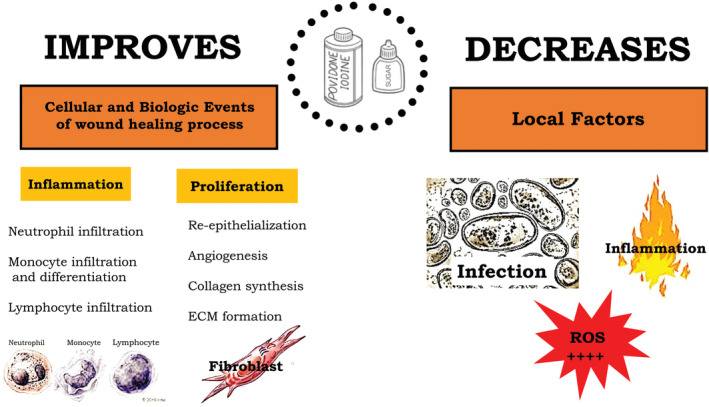

Knutson's formula is based on a combination of povidone‐iodine and sugar. The former, through its antiseptic activity, contributes to preserving the area from bacterial infections during the healing process.5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 The latter is known for its anti‐inflammatory and antimicrobial proprieties12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 18 and its ability to stimulate cell proliferation, collagen synthesis, and neo‐angiogenesis. These modifications in skin structures promote wound contraction25 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

This illustration summarises the effects of povidone‐iodine and sugar on the wound‐healing process

We observed statistically significant differences in the abilities of povidone‐iodine and sugar solution to treat surgical wound dehiscence in the head and neck when compared with the standard topical treatment; in particular, we noted a reduced time to complete wound closure, better wound conditions since the 3rd day (T1) of follow up, and the complete absence of bacterial infections during the entire period of treatment.

The wounds treated with Knutson's formula presented a rapid decrease of the exudate and an early skin regeneration process as showed by the presence of intensive granulation, new pink regenerative tissue, and reduced deepness of wound.

In the study group, we observed a complete resolution of wound deficit without alterations of the scar process in all cases at T5; complete resolution was also observed in the two cases that underwent skin flap. We speculate that, in these two cases, even if povidone‐iodine and sugar solution was unable to determine complete skin closure, its components may have improved the skin tropism that favoured the complete closure of the dehiscence after flap surgery. It is important to underline that all patients in the study group were treated with povidone‐iodine and sugar solution for 15 days only, so the healing process progressed spontaneously even after the suspension of the treatment.

Patients in the control group, although treated for a longer time compared with those in the study group, presented complete resolution of wound dehiscence in three cases only (18.7%) after 30 days. Furthermore, three patients in this group needed systemic antibiotic treatment because of the persistence of a bacterial infection in the wound area.

Overall, our results suggest that the mixture of povidone‐iodine and sugar may be more efficient than traditional topical treatment to treat wound dehiscence in the head and neck region of patients treated with radio‐chemotherapy after surgical removal of a tumour. We speculate that the positive effects of povidone‐iodine and sugar solution may be due to the combination of these two substances.

Knutson's formula is easy to prepare, contains ingredients available both in the industrialised and not‐industrialised countries, is easily accessible, and has a low price. The use of this formula may reduce the health costs by maintaining a high standard of treatment. Further studies on larger samples are necessary to confirm these results and evaluate the variability of the results of the treatment with povidone‐iodine and sugar solution.

4.1. Limits of the study

This study presents several limitations. The major limitations were the absence of multivariate analysis for evaluating the impact of size and location on the outcomes and statistical analysis on the impact of comorbidities (systemic disease or drugs use) in the healing process. Minor limits include the small sample size and the absence of comparison between different operators in treatment execution and results (ie, nurse versus physician).

5. CONCLUSION

Our data suggest that povidone‐iodine and sugar solution may have better results compared with antibacterial topical medications to treat surgical wound dehiscence in oncological patients who underwent radio‐chemotherapy. In our sample, the formula increased the granulation tissue proliferation, avoided wound superinfection, and restored the spontaneous healing process that is also maintained after treatment suspension.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We especially thank Dr Paolo Pettirossi and Sauro Giommetti for their help in collection of clinical data.

Di Stadio A, Gambacorta V, Cristi MC, et al. The use of povidone‐iodine and sugar solution in surgical wound dehiscence in the head and neck following radio‐chemotherapy. Int Wound J. 2019;16:909–915. 10.1111/iwj.13118

This work has been performed in the Otolaryngology Department of the Silvestrini University hospital, University of Perugia.

REFERENCES

- 1. Zamora JL. Chemical and microbiologic characteristics and toxicity of povidone‐iodine solutions. Am J Surg. 1986;151(3):400‐406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schubert R. Disinfectant properties of new povidone‐iodine preparations. J Hosp Infect. 1985;6(suppl A):33‐36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Berkelman RL, Holland BW, Anderson RL. Increased bactericidal activity of dilute preparations of povidone‐iodine solutions. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;15(4):635‐639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rodeheaver G, Bellamy W, Kody M, et al. Bactericidal activity and toxicity of iodine‐containing solutions in wounds. Arch Surg. 1982;117(2):181‐186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dedo DD, Alonso WA, Ogura JH. Povidone‐iodine: an adjunct in the treatment of wound infections, dehiscences, and fistulas in head and neck surgery. Trans Sect Otolaryngol Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1977;84:68‐74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bigliardi P, Langer S, Cruz JJ, Kim SW, Nair H, Srisawasdi G. An Asian perspective on Povidone iodine in wound healing. Dermatology. 2017;233(2–3):223‐233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bigliardi PL, Alsagoff SAL, El‐Kafrawi HY, Pyon JK, Wa CTC, Villa MA. Povidone iodine in wound healing: a review of current concepts and practices. Int J Surg. 2017;44:260‐268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Williamson DA, Carter GP, Howden BP. Current and emerging topical Antibacterials and antiseptics: agents, action, and resistance patterns. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017;30(3):827‐860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fourtillan E, Tauveron V, Binois R, Lehr‐Drylewicz AM, Machet L. Treatment of superficial bacterial cutaneous infections: a survey among general practitioners in France. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2013;140(12):755‐762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wilkins RG, Unverdorben M. Wound cleaning and wound healing: a concise review. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2013;26(4):160‐163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goldenheim PD. An appraisal of povidone‐iodine and wound healing. Postgrad Med J. 1993;69(suppl 3):S97‐S105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chirife J, Herszage L, Joseph A, Kohn ES. In vitro study of bacterial growth inhibition in concentrated sugar solutions: microbiological basis for the use of sugar in treating infected wounds. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1983;23(5):766‐773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Haddad MC, Vannuchi MT, Chenso MZ, Hauly MC. The use of sugar in infected wounds. Rev Bras Enferm. 1983;36(2):152‐154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chirife J, Herszage L. Sugar for infected wounds. Lancet. 1982;2(8290):157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chirife J, Scarmato G, Herszage L. Scientific basis for use of granulated sugar in treatment of infected wounds. Lancet. 1982;1(8271):560‐561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jull AB, Walker N, Deshpande S. Honey as a topical treatment for wounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2:CD005083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jull AB, Rodgers A, Walker N. Honey as a topical treatment for wounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;4:CD005083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tovey F. Honey and sugar as a dressing for wounds and ulcers. Trop Doct. 2000;30(1):1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kamat N. Use of sugar in infected wounds. Trop Doct. 1993;23(4):185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Knutson RA, Merbitz LA, Creekmore MA, Snipes HG. Use of sugar and povidone‐iodine to enhance wound healing: five year's experience. South Med J. 1981;74(11):1329‐1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shi CM, Nakao H, Yamazaki M, Tsuboi R, Ogawa H. Mixture of sugar and povidone‐iodine stimulates healing of MRSA‐infected skin ulcers on db/db mice. Arch Dermatol Res. 2007;299(9):449‐456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nakao H, Yamazaki M, Tsuboi R, Ogawa H. Mixture of sugar and povidone–iodine stimulates wound healing by activating keratinocytes and fibroblast functions. Arch Dermatol Res. 2006;298(4):175‐182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lazarus GS, Cooper DM, Knighton DR, Percoraro RE, Rodeheaver G, Robson MC. Definitions and guidelines for assessment of wounds and evaluation of healing. Wound Repair Regen. 1994;2(3):165‐170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Payne WG, Naidu DK, Wheeler CK, et al. Wound healing in patients with cancer. Eplasty. 2008;8:e9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pereira RF, Bartolo PJ. Traditional therapies for skin wound healing. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2016;5(5):208‐229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]