Abstract

Adults with developmental disabilities face barriers to making healthy lifestyle choices that mirror the barriers faced by the direct support professionals who serve them. These two populations, direct support professionals and adults with developmental disabilities, are likely to lead inactive lifestyles, eat unhealthy diets, and be obese. Moreover, direct support professionals influence the nutrition knowledge, attitudes, and health behaviors of the adults with developmental disabilities whom they serve. We piloted a cooking-based nutrition education program, Cooking Matters for Adults, to dyads of adults with developmental disabilities (n = 8) and direct support professionals (n = 7). Team-taught by a volunteer chef and nutrition educator, Cooking Matters for Adults uses an active learning approach to teach food preparation safety skills and nutrition knowledge to inform healthy food and beverage choices. We assessed healthy food preparation, intake of a balanced diet, healthy food and beverage choices, and cooking confidence and barriers at pre-test, post-test, and 6-months after the intervention. Among both adults with developmental disabilities and direct support professionals, positive trends in healthy food preparation, eating a balanced diet, and reduction in cooking barriers were observed at post-test and 6-months. We also qualitatively assessed knowledge of and attitudes toward healthy eating, frequency of food and beverage intake, knowledge about kitchen skills and safety, as well as overall satisfaction, cooking confidence, and acceptability of the dyad approach. Participants with developmental disabilities and direct support professionals reported that they learned about healthy food and beverage choices and various cooking skills. Participants reported confidence in skills learned and were satisfied with the intervention and approach of including adults with developmental disabilities and direct support professionals in the intervention together.

Keywords: Cooking Matters for Adults, developmental disabilities, direct support professionals, cooking intervention, nutrition, health education

Health-compromising behaviors negatively impact the health of direct support professionals (DSPs) and of the adults with developmental disabilities (DD) whom they serve. DSPs are at the front line of service provision for adults with DD, assisting in activities of daily living and community participation. DSPs can have a large social role1,2 and may impact the health behavior of their clients with DD.3 In fact, health-compromising behaviors such as eating unhealthy diets may be modeled and reinforced by DSPs.3

Adults with DD view DSPs as important sources of both emotional and practical support.1,2 These relationships have been documented to impact the health behavior of adults with DD,3 providing an important opportunity to improve the health of adults with DD and DSPs. This research aligns with Bandura’s4 work investigating health promotion through Social Cognitive Theory. More specifically, Social Cognitive Theory contends that peers in a social network are influenced by the behaviors of those around them by way of role modeling, serving to reinforce both health-promoting and health-compromising behaviors. Importantly, peers can keep one another accountable to achieve meaningful behavior change.4 Thus, with the appropriate training, DSPs could adopt and support meaningful, positive behavior changes in diet and cooking skills for both themselves and the people with DD for whom they provide care.

The health of adults with DD and DSPs is noted for high rates of inactivity, eating unhealthy diets,3,5–8 and obesity.9 Moreover, health-promoting behaviors such as eating diets rich in fruits and vegetables are lacking among adults with DD and DSPs.3,7,8 There is a growing body of research highlighting the need for cooking skills and nutrition knowledge to bolster healthier eating patterns among people without disabilities.10,11 Evidence supports the use of Social Cognitive Theory in the design of health promotion interventions for people with DD.12 Recent work by Jo and colleagues12 examined the utility of a physical activity intervention based on Social Cognitive Theory to improve muscle endurance, self-efficacy, and physical activity levels. Increased self-efficacy, as well as key improvements in physical activity outcomes, were noted at post-test, highlighting the potential effectiveness of the Social Cognitive Theory framework for other health promotion interventions in this population.12 Social Cognitive Theory was used to inform a nutrition, physical activity, and weight loss intervention (Web-Based Guide to Health) in people without disabilities, which identified social support as a critical factor in the maintenance of healthy choices.13 However, evidence for nutrition and cooking-based health promotion interventions for people with DD is lacking in the literature. The purpose of this study was to pilot Cooking Matters in a dyad format to assess the degree to which the intervention is feasible and acceptable among adults with DD and DSPs. We also endeavored to explore the usefulness of health promotion interventions like Cooking Matters to meaningfully change health behavior in adults with DD for the better.12

Cooking Matters for Adults is a cooking-based nutrition education program developed by Share Our Strength to help families shop for and cook healthy meals on a budget.14,15 Designed for people with low literacy, Cooking Matters teaches food preparation safety skills in the kitchen including the use of knifes and stoves, and nutrition knowledge informing healthy food and beverage choices. The active learning design of Cooking Matters is well suited for many learners, including adults with disabilities. Yet, to date, no research has investigated the potential for Cooking Matters to improve these skills in people with DD.

This pilot study evaluated the satisfaction and acceptability of offering Cooking Matters to dyads of adults with DD and their DSPs to expand on previous work examining this influential relationship.1,2 One goal of this study was to explore the potential for Cooking Matters to improve healthy food preparation, increase both a balanced diet and healthy food and beverage choices, increase cooking confidence, and reduce barriers to cooking among adults with DD. We assessed nutrition knowledge, cooking skills, and attitudes toward the importance of a healthy diet at pre-test, post-test, and 6-month follow-up.

Method

Participants

In 2017, adults with DD and DSPs were recruited in dyads from a DD provider organization in Columbus, Ohio, to participate in the Cooking Matters pilot. To be included in this study, adults with DD had to live in a supported living setting or in a group home and receive regular support from a DSP. In Ohio, DD was defined as severe, chronic disabilities attributable to mental or physical impairment; developed before age 22; expected to be life long and is the result of functional limitations in at least 3 areas of major life activity such as self-care, receptive and expressive language, learning, mobility, self-direction, ability to live independently, and economic self-sufficiency.16 Adults with DD in our sample varied in their level of independence; most relied on some degree of support from DSPs to plan and prepare meals. When asked about disability type, all adults in the DD group reported having DD and one adult reported having intellectual disability as well. DSP was defined as paid staff that had primary responsibility for assisting the adult(s) with DD with activities of daily living. Both adults with DD and DSPs participated in the intervention and assessment. A total of 8 adults with DD (Mage = 51.88, SDage = 5.94; 3 males; 87.5% Caucasian) and 7 DSPs (Mage = 47.14, SDage = 9.94; 1 male; 100% African American) participated in this study.

DSPs varied in educational background from a high school degree (n = 1) to some college coursework (n = 3) to a 2-year college degree (n = 3). Some DSPs indicated they received federal assistance from Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) (n = 2); some indicated they received federal assistance from Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) (n = 2); and some indicated they received assistance from Medicaid (n = 3). DSPs’ average household size was approximately 3.6 while average household size among adults with DD was approximately 2.5. One DSP provided care for 2 participants with DD, and the other 6 DSPs provided care to only one adult with DD. All participants completed the pre-, post-, and 6-month follow-up assessments except 2 DSPs that were lost to follow-up 6 months after the intervention.

Procedure

This study was approved by the University’s institutional review board, protocol #2016B0371, and written informed consent was obtained by research staff from all participants or their legal guardian. Quantitative surveys and qualitative semi-structured interviews were administered at pre-test, post-test, and 6-month time points. Participants were asked to limit engagement in cooking/nutrition interventions to Cooking Matters for the duration of this study.

Intervention

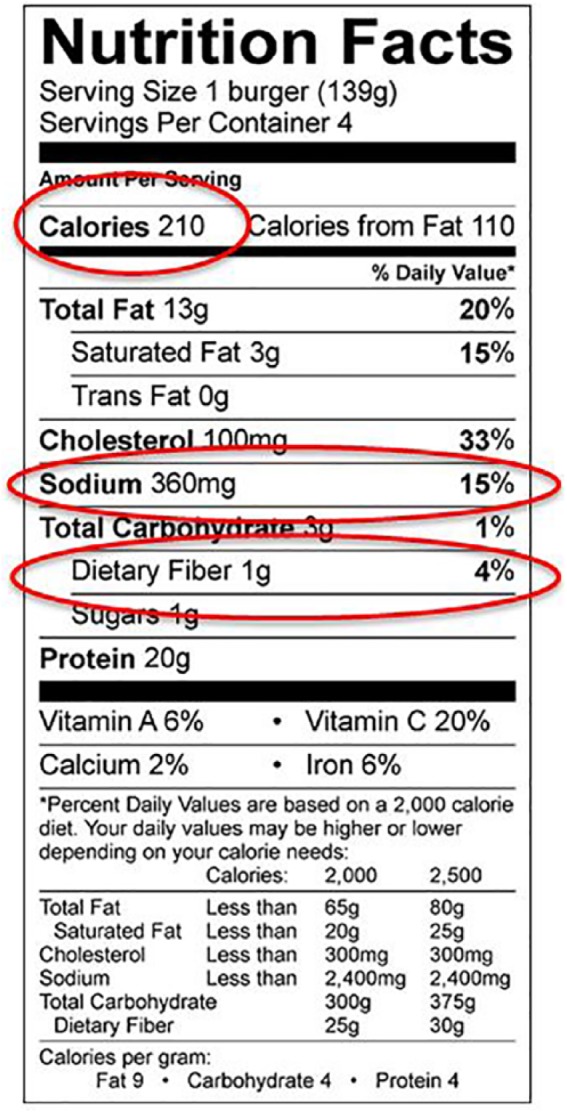

Cooking Matters for Adults, developed by Share Our Strength, is a 6-week intervention designed to help low-income adults learn about healthy eating and cooking while also learning how both can be managed to eat healthy on a limited budget.17 Team-taught by a volunteer chef and a nutrition educator, the Cooking Matters class content included meal preparation, grocery shopping, food budgeting, and nutrition. The class was held once a week in the evening for 2 hours. Before and after each class, a member of the research team with DD expertise met with the volunteer chef and nutrition educator to provide suggestions on using accessible language for participants with DD. The ongoing consultation with the research team helped to ensure the Cooking Matters program was accessible for adults with DD. The authors also worked with Local Matters, an affiliate of Share Our Strength, to adapt the curriculum for adults with DD. First, visual aids were used to demonstrate key concepts. For example, recipes were adapted to include pictures of food and measurements (see Appendix 1). We adapted directions for preparing the recipe using short sentences and simple vocabulary. Second, nutritional labels were simplified and enlarged to draw attention to key elements such as calories, sodium, and fiber (see Appendix 2). Finally, recipes were chosen in collaboration with participants. Importantly, some people with DD have sensitivity to specific food textures, and so involving participants with DD in the recipe decision making ensured accessible meal preparation. Overall, the identified changes to the program were minor and consistent with the intent for Cooking Matters to be accessible to adults with low literacy.17 Adults with DD engaged in every aspect of food preparation including cutting, mixing, and stove top cooking.

Measures

Cooking Matters for Adults survey

Cooking Matters for Adults survey was developed by Share Our Strength to evaluate the Cooking Matters program.18,19 This survey measured healthy food preparation (8 items), balanced diet (10 items), healthy choices (6 items), cooking confidence (4 items), and cooking barriers (3 items) subscales. Healthy food preparation subscale assessed nutritional food preparation and healthy eating behavior. Balanced diet subscale assessed frequency of food and beverage intake, including healthy and unhealthy options, and healthy choices subscale assessed frequency of choosing low-fat, low-sodium, and other healthy food options. Finally, the cooking confidence subscale assessed confidence with cooking skills and preparing and buying healthy foods; and the cooking barriers subscale assessed participants’ frustration with cooking and beliefs around how much time it takes to cook and difficulty of cooking. All items were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale; 6 items (3 from balanced diet and 3 from cooking barriers subscales) were reverse scored so that higher scores were indicative of improvement across all items.

We adapted the Cooking Matters for Adults survey to improve cognitive accessibility for participants with DD. Item stems were shortened and simplified and pictures were added that were consistent with published guidelines.20 See Appendix 3 for a sample of the adapted Cooking Matters survey. The Flesch-Kincaid reading level of the adapted survey measured at a 4.4 grade level. Research staff read surveys aloud to participants with DD. DSPs completed the written survey independently.

Interviews

A semi-structured interview was developed for this study to assess knowledge of and attitudes toward healthy eating, frequency of food and beverage intake, and knowledge about kitchen skills and safety. At the post-test and 6-month time points, additional questions assessed overall satisfaction, cooking confidence, and acceptability of the dyad approach. Research staff administered the semi-structured interviews one-on-one to both adults with DD and DSPs. Interview responses were recorded verbatim.

Results

We assessed satisfaction with the Cooking Matters class and participant acceptance of the dyad approach. All participants (100%) indicated they liked the program, especially the cooking portion of the class and the healthy recipes. Participants enjoyed the opportunity to learn and practice healthy cooking in dyads of adults with DD and DSPs. See Table 1 for direct quotes by adults with DD and DSPs supporting satisfaction, confidence, and acceptance of Cooking Matters for dyads.

Table 1.

Selected quotes from adults with developmental disabilities and direct support professionals on satisfaction, confidence, and acceptability of cooking matters in dyads.

| Adults with developmental disabilities | Direct support professionals | |

|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction | ● “[I] liked that you got to cook and eat what you made, no

dislikes.” ● “[I] liked learning how to cook and about the meals made.” |

● “Enjoyed the whole thing . . . ” ● “Eye-opening, really enjoyed the whole class; learned to be creative and try new things.” |

| Confidence | ● “[Cooking Matters was] pretty good, I do

better with cooking.” ● “Talking about the meals we made . . . I like making meals now . . . cutting vegetables . . . stirring the pan.” |

● “It’s an eye opener, you think you know everything until you

learn something new like how to cook with tofu or cutting

vegetables and avoiding enriched products.” ● “I learned some different things that I wasn’t aware of like cooking with veggies and fruits, and I’m good at it now.” |

| Acceptability | ● “Liked working with different people, the

staff.” ● “Staff was friendly and I liked working with them; they helped me learn how to cook on a budget.” |

● “No dislikes, really enjoyed working with residents, and the

residents enjoyed the class.” ● “Everyone interacted as a team, learning new things together . . . ” |

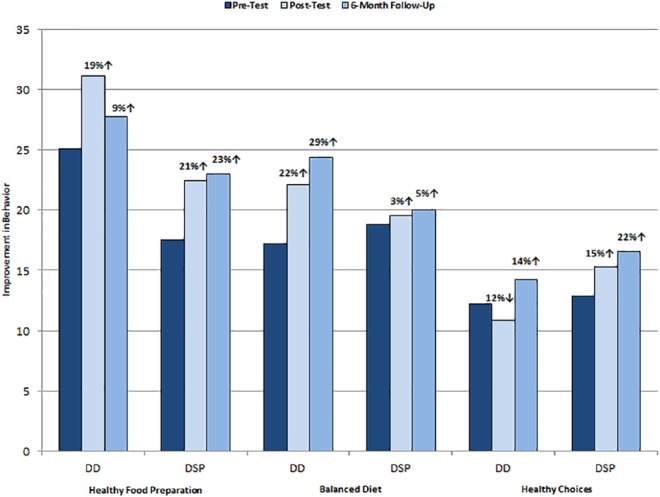

We examined percent changes in summed scores for the three survey subscales: healthy food preparation, balanced diet, and healthy choices across three time points for adults with DD and DSPs (see Figure 1). Among adults with DD, non-significant trends toward improvement at post-test were observed for healthy food preparation and balanced diet but not healthy choices. DSPs showed non-significant trends toward improvement at post-test across all subscales. Importantly, across both groups, these effects were partially maintained at the 6-month follow-up. For instance, adults with DD maintained a small improvement in healthy food preparation over baseline and a continued improvement on balanced diet. From post-test to 6 months, adults with DD showed a slight improvement healthy choices. DSPs maintained improvements in healthy food preparation, eating a balanced diet, and making healthy choices at the 6-month follow-up.

Figure 1.

Findings from Cooking Matters for Adults survey at pre-test, post-test, and 6-month follow-up for adults with developmental disabilities and direct support professionals. DD indicates adults with developmental disabilities; DSP, direct support professionals. Scores at post-test are percent changes compared with pre-test. Scores at 6-month follow-up are percent changes compared with pre-test.

Recognizing that the small sample size left this pilot study underpowered to detect statistical significance, a power analysis was performed for sample size estimation based on these data comparing pre-post impact of the program on adults with DD and DSPs. The effect size for the 3 knowledge (Healthy Food Preparation, Balanced Diet, and Healthy Choices) subscales was .3; the projected sample size needed to detect significant differences with an alpha = –.5 and power = .8 is approximately N = 82.

Qualitative findings from participant interviews were more striking. From pre-test to post-test, DSPs and adults with DD were more likely to list specific behaviors that underlie healthy eating and describe health benefits associated with healthy eating. For example, participants from both groups named the following behaviors: eat a balanced diet, avoid “junk” food, healthy cooking, and eating healthy on a budget. Adults with DD and DSPs listed benefits of healthy eating including lower cholesterol, weight loss, heart health, and improved quality of life. At post-test, participants described cooking skills they learned such as washing hands before prepping foods, wearing gloves, properly cleaning and cutting foods, following a recipe, cleanliness, and being vigilant while food is cooking. These improvements in nutrition knowledge and cooking skills were maintained at 6-month follow-up.

We also assessed cooking confidence and cooking barriers among adults with DD and DSPs (not displayed). Among adults with DD, cooking confidence increased 13%, but these effects dropped off at 6 months (–14%) compared with pre-test. Among DSPs, a nominal improvement was noted at post-test in cooking confidence (3% increase); this trend continued at 6-month follow-up (10% increase from pre-test). For adults with DD, a 34% reduction in cooking barriers was noted at post-test and these effects were maintained at 6 months (41% decrease from pre-test). For DSPs there was an initial non-significant trend toward improvement in cooking barriers at post-test (10% reduction in reported barriers), but these effects dropped off at 6 months (28% increase in barriers). In post-test and 6-month follow-up interviews, both DSPs and adults with DD described feeling more confident about their cooking skills.

Discussion

This pilot study demonstrates the feasibility and acceptability of offering a health education program, Cooking Matters, to inclusive groups of adults with DD and their DSPs. This study contributes to the body of evidence on the importance of the relationship between adults with DD and DSPs. The strong emotional bonds that often characterize this relationship provide an opportunity for positive coaching, role modeling, and behavior change accountability.1,2 Health behaviors of DSPs could serve as key barriers or facilitators of meaningful healthy choices made by adults with DD.21,22 Our approach of offering Cooking Matters to dyads of adults with DD and their DSPs has implications for inclusive health education programming in environments where DSPs support adults with DD such as residential or vocational settings.

We assessed nutrition knowledge, cooking skills, as well as confidence and perceived cooking barriers before and after participating in Cooking Matters and at a 6-month follow-up. Positive trends were noted among adults with DD and DSPs, although this study was underpowered to detect statistically significant changes. Importantly, qualitative data complement quantitative findings of improved healthy food preparation and eating a balanced diet among adults with DD and DSPs. For instance, rich qualitative data at post-test and 6-months highlight specific behaviors that underlie healthy food preparation (e.g., eating healthy food on a budget) and the importance of eating a balanced diet (e.g., avoiding “junk” food, eating foods from every food group). These findings are important given the growing body of literature highlighting the need for cooking skills and nutrition knowledge to combat poor diet and improve health.10,11

There were limitations to this study that should be considered when interpreting our results. First, the small sample size for this pilot study limits the generalizability of these findings. Future research is needed to replicate this dyadic approach with larger, more heterogeneous samples. Second, although the Cooking Matters intervention was offered by trained Local Matters staff who considered the cognitive accommodations to be minor, this study would have been strengthened by measuring the fidelity of the adapted Cooking Matters intervention. Despite these limitations, this study makes an important contribution to the literature by demonstrating that a health education program offered to adults with DD and their DSPs can have a positive impact on health behavior. We have shown that a health education program offered to adults with DD and DSPs can be practical, acceptable, and possibly, better together.

Acknowledgments

The research team would like to thank the individuals who participated in this study and our partner, Local Matters, whose generous collaboration made this project possible. We are grateful to Ann C. Robinson and Amanda Hager for their contributions to this study.

Appendix

Appendix 1.

Excerpts of an Adapted Cooking Matters Recipe.

| Pictures of ingredients and quantity | |

|---|---|

| ¼ small bell pepper | ¼ small red onion |

|

|

| Simplified cooking instructions | |

| 1. Wash bell pepper and onion. 2. Chop bell pepper and onion into small pieces. 3. In a large skillet, combine all ingredients. | |

| Pictures of needed cooking supplies | |

| Cutting board | Large skillet with lid |

|

|

Appendix 2.

Accessible nutrition facts from an Adapted Cooking Matters Recipe.

Appendix 3.

Excerpts from the Adapted Cooking Matters Survey.

| How often do you eat . . . | Not at all | Once a week or less | More than once a week | Once a day | More than once a day |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1. . . . fruits like apples, bananas, melon, or other

fruit?

|

▯ | ▯ | ▯ | ▯ | ▯ |

2. . . . green salad?

|

▯ | ▯ | ▯ | ▯ | ▯ |

3. . . . french fries or other fried potatoes, like home fries,

hash browns, or tater tots?

|

▯ | ▯ | ▯ | ▯ | ▯ |

4. . . . any other kind of potatoes that aren’t

fried?

|

▯ | ▯ | ▯ | ▯ | ▯ |

5. . . . refried beans, baked beans, pinto beans, black beans,

or other cooked beans? (Not green beans or string

beans.)

|

▯ | ▯ | ▯ | ▯ | ▯ |

Footnotes

Funding:This project was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Cooperative Agreement No. 2U59DD000931-04.

Declaration of conflicting interests:The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Author Contributions: SMH and EAY designed and coordinated the study protocol. WRB and EAY collected the data, and AL conducted the statistical analyses. WRB and SMH drafted the manuscript. All authors helped in drafting the manuscript, and all authors approved the final draft.

References

- 1. De Schipper JC, Schuengel C. Attachment behaviour towards support staff in young people with intellectual disabilities: associations with challenging behaviour. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2010;54:584–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hewitt A, Larson S. The direct support workforce in community supports to individuals with developmental disabilities: issues, implications, and promising practices. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2007;13:178–187. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Leser KA, Pirie PL, Ferketich AK, Havercamp SM, Wewers ME. Dietary and physical activity behaviors of adults with developmental disabilities and their direct support professional providers. Disabil Health J. 2017;10:532–541. 10.1016/j.dhjo.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bandura A. Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychol Health. 1998;13:623–649. 10.1080/08870449808407422. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Draheim CC, Williams DP, McCubbin JA. Prevalence of physical inactivity and recommended physical activity in community-based adults with mental retardation. Ment Retard. 2002;40:436–444. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gallant MP, Connell CM. Predictors of decreased self-care among spouse caregivers of older adults with dementing illnesses. J Aging Health. 1997;9:373–395. doi: 10.1177/089826439700900306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Perera BD, Standen PJ. Exploring coping strategies of carers looking after people with intellectual disabilities and dementia. Adv Mental Health Intell Disabil. 2014;8:292–301. doi: 10.1108/AMHID-05-2013-0034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Robertson J, Emerson E, Gregory N, et al. Lifestyle related risk factors for poor health in residential settings for people with intellectual disabilities. Res Dev Disabil. 2000;21:469–486. doi: 10.1016/S0891-4222(00)00053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ells LJ, Lang R, Shield JP, et al. Obesity and disability—a short review. Obes Rev. 2006;7:341–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Utter J, Denny S, Lucassen M, Dyson B. Adolescent cooking abilities and behaviors: associations with nutrition and emotional well-being. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2016;48:35–41.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2015.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wrieden WL, Anderson AS, Longbottom PJ, et al. The impact of a community-based food skills intervention on cooking confidence, food preparation methods and dietary choices—an exploratory trial. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10:203–211. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007246658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jo G, Rossow-Kimball B, Lee Y. Effects of 12-week combined exercise program on self-efficacy, physical activity level, and health related physical fitness of adults with intellectual disability. J Exerc Rehabil. 2018;14:175–182. doi: 10.12965/jer.1835194.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Anderson-Bill ES, Winett RA, Wojcik JR. Social cognitive determinants of nutrition and physical activity among web-health users enrolling in an online intervention: the influences of social support, self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and self-regulation. J Med Intern Res. 2011;13:e28. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pooler JA, Morgan RE, Wong K, Wilkin MK, Blitstein JL. Cooking Matters for Adults improves food resource management skills and self-confidence among low-income participants. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2017;49:545–553.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2017.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Reicks M, Trofholz AC, Stang JS, Laska MN. Impact of cooking and home food preparation interventions among adults: outcomes and implications for future programs. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2014;46:259–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. The Developmental Disabilities Assistance Bill of Rights Act of 2000. ACL. https://acl.gov/about-acl/authorizing-statutes/developmental-disabilities-assistance-and-bill-rights-act-2000. Accessed December 18, 2018.

- 17. Cooking Matters. https://cookingmatters.org/. Accessed December 18, 2018.

- 18. Murray EK, Auld G, Baker SS, et al. Methodology for developing a new EFNEP food and physical activity behaviors questionnaire. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2017;49:777–783.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2017.05.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pinard CA, Uvena LM, Quam JB, Smith TM, Yaroch AL. Development and testing of a revised cooking matters for adults survey. Am J Health Behav. 2015;39:866–873. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.39.6.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Department of Health. Making written information easier to understand for people with learning disabilities. London: Department of Health, Government of UK; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kneringer M-J, Page TJ. Improving staff nutritional practices in community-based group homes: evaluation, training, and management. J Appl Behav Anal. 1999;32:221–224. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1999.32-221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Martin E, McKenzie K, Newman E, Bowden K, Morris PG. Care staff intentions to support adults with an intellectual disability to engage in physical activity: an application of the theory of planned behaviour. Res Dev Disabil. 2011;32:2535–2541. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]