Abstract

An 8-month-old child was admitted to a paediatric intensive care unit in Guinea-Bissau with severe blistering dermatosis. He was treated with broad spectrum antibiotics and dressings, without improvement. After 2 weeks, linear IgA bullous dermatosis was suspected. Owing to lack of dapsone, the child was treated with prednisolone and improved. To avoid corticosteroids side effects, 2 months after starting prednisolone we switched to colchicine, but the boy’s condition worsened for reasons of poor adherence, requiring intravenous corticosteroids and antibiotics. After complete resolution of the skin lesions, we continued with colchicine monotherapy, then changed to dapsone after 3 months. The child did not show any further signs of dermatosis, but his follow-up ended abruptly, because he did not return to the hospital. IgA bullous dermatosis is a challenging diagnosis in settings where pathological studies cannot be conducted. Multidisciplinary treatment is required and colchicine is a good option if dapsone is not available.

INTRODUCTION

IgA bullous dermatosis, also known as chronic bullous disease of childhood, is a relatively rare, chronic, subepidermal blistering disease of childhood that may be drug-induced or idiopathic [1]. Although still relatively rare, it is among the most common acquired immunobullous conditions in children, and most of the evidence comes from case reports and case series. There is a higher incidence in Africa, China and South East Asia [2]. In children, the disease usually presents between the ages of 6 months and 10 years, with neonates rarely affected [3]. It can be a challenging diagnosis in resource-limited settings if pathological studies cannot be performed. Regarding prognosis, although the condition can be seriously debilitating or even fatal, remission has been reported in 64% of children, usually within 2 years. The disorder often remits by age 6–8 years and in most cases by adolescence [4], often curing without sequelae [5]. Prompt differential diagnosis is essential since skin lesions in linear IgA dermatosis may respond rapidly when treated with dapsone, sulfapyridine or colchicine [6].

With the support of a dermatologist via Telemedicine, we suspected bullous dermatosis in a male infant, based on the patient’s clinical history and examination. We prescribed empiric treatment, with successful results and complete resolution of skin lesions after 7 months.

PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS

An 8-month-old boy, without relevant past personal or family medical history, was admitted to the paediatric intensive care unit of a health facility in Guinea-Bissau presenting a severe and disseminated blistering dermatosis of 1 month’s evolution, fever and ill appearance for the previous 3 days.

CLINICAL FINDINGS

As described in the literature, disseminated itchy lesions were noted, starting as tense blisters arranged annularly, a formation referred to as a ‘crown of jewels’ like pattern of 1 cm [7]. These blisters left a hypochromic target after healing, and affected the lower abdomen, anogenital area (including perineum), face, chest, upper and lower limbs, without involvement of palms or soles of the feet. No mucosal surfaces were affected.

DIAGNOSTIC ASSESSMENT

Usually, diagnosis of linear IgA bullous dermatosis can be aided by clinical, histopathological and immunological data. However, these tests were unavailable in our clinic. Haemoglobin and random blood sugar were normal on admission. With no dermatologist in the team, we initially managed the case as a cutaneous infection, treating the patient with corticotherapy and systemic antibiotic while we shared the case with the MSF Telemedicine Platform. We suspected also a polymorphic erythema, but the clinical evolution was atypical. Although any infectious, autoimmune, or genetic blistering can enter into differential diagnosis, IgA bullous dermatosis needs to be differentiated clinically and pathologically from two other blistering autoimmune skin diseases: dermatitis herpetiformis (DH) and bullous pemphigoid (BP) [8]. Differential diagnosis needs also to account for toxic epidermical necrolysis and inherited skin fragility diseases such as epidermolysis bullosa acquisita and epidermolysis bullosa.

Distinguishing bullous dermatosis from DH is generally not difficult clinically, and although both diseases are characterized by IgA deposits, there are important differences between them. DH is associated with a gluten-sensitive enteropathy in almost all cases which responds to a gluten-free diet, whereas with IgA bullous dermatosis there is no such association [9]. The IgA found in the skin of DH is in granular deposits in the dermal papillae and no-circulating BMZ-specific antibodies have been detected. Thus, whereas DH and IgA bullous dermatosis share some features, they differ significantly with regard to immunopathology [10]. The differential diagnosis from BP, however, may be difficult clinically, since BP has a linear IgG BMZ deposition, while IgA bullous dermatosis has a linear IgA deposition.

With the help of the Telemedicine dermatologist, we thus suspected IgA bullous dermatosis and began specific treatment.

THERAPEUTIC INTERVENTION

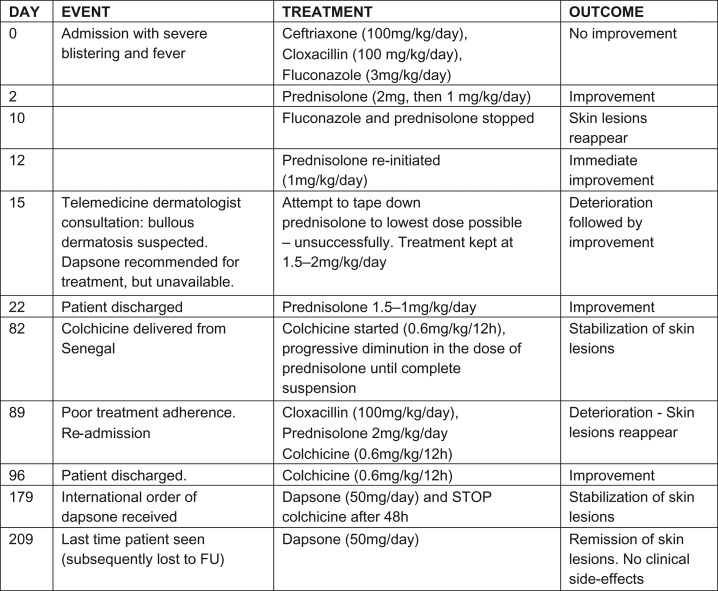

On admission (Fig. 2), the patient had received intravenous treatment with cloxacillin, fluconazole and ceftriaxone (a gram-negative cocci was isolated from blister fluid) and dressings, without any improvement (Fig. 1). When bullous dermatosis was suspected, we started treatment with prednisolone, since the first-line drug—dapsone—is unavailable in Guinea-Bissau. After 24 h of treatment, the patient improved dramatically (Fig. 3). However, to avoid long-term side effects of corticotherapy, we tried to withdraw prednisolone. Unsuccesfully, this caused worsening and proliferation of blisters.

Figure 2:

At admission. *Note: ‘crown of jewels’ blistering pattern.

Figure 1:

Timeline.

Figure 3:

After three weeks’ treatment with prednisolone.

Importantly, analgesic treatment was also necessary as the blisters can be very painful.

After 2 months, we started second-line treatment with oral colchicine. Initially, the patient’s condition deteriorated as the mother was not adhering correctly to the prescribed medicine, did not bring the child in for follow-up, and even interrupted the treatment. Therefore, the child had to be readmitted to our clinic. Five days after intravenous corticotherapy and antibiotherapy in addition to colchicine, he began to improve slowly and his lesions resolved after 7 days (Fig. 4). He then continued on colchicine only and his family was informed of the importance of following the treatment regimen.

Figure 4:

After 5 weeks under colchicine.

After 3 months under colchicine without side effects, we were able to switch the patient to dapsone. Two weeks later, he had no more signs of dermatosis and had therefore been free of lesions for 4 months (Fig. 5) and without any clinical side-effects (no blood count was available). At this point, we insisted on the continuation of medication without interruption as well as follow-up visits, but despite phone calls, the child was never brought back.

Figure 5:

After 2 weeks under dapsone (usual first-line treatment, but was not available in this setting).

DISCUSSION

For this child, we suspected IgA bullous dermatosis as it is the most common autoimmune bullous disorder in children, and relatively frequent in Africa. Confirming such a diagnosis in resource-limited settings is difficult, since histopathological and immunological testing is usually not available [9]. Treating bullous dermatosis in a resource-limited setting is also challenging, since it requires specific multidisciplinary treatment and monitoring of side-effects which is not always possible. This was one of our limitations, since we could not perform a skin biopsy due to the lack of a well-trained specialist and proper equipment to perform it in Guinea-Bissau. However, the photographs taken of the child’s skin show a dramatic improvement with dapsone.

Fortunately in this case, there was no mucosal involvement. Bullous dermatosis can affect any mucosal surface, particularly ocular and oral surfaces, although this is rare in children. If mucosal surfaces are affected, further specialist input and follow-up may be required as there is a risk of blindness and pharyngolaryngeal stenosis [5]. Dapsone is the first-line drug to be used, but prior to its initiation patients should be screened for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, as patients with decreased activity of this enzyme show an ~2-fold increased sensitivity for developing haemolysis. Blood count also should be checked, since dapsone can cause severe haematological toxicity [11]. In our context these tests were not possible. Because dapsone was unavailable to begin with, we used colchicine as a second-line with successful results, as has been documented elsewhere [12]. On the basis of this case, we can confirm that colchicine is a good choice if dapsone is unavailable. Although our case had a favourable outcome, we could not perform long-term follow-up since the patient never came back to our facility.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the assistance of the MSF Telemedicine Platform specialists who provided precious guidance in diagnosis and case management. We thank also Marta A. Balinska for her editorial assistance.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

FUNDING

This study was entirely funded by Médecins Sans Frontières Operational Center Barcelona–Athens.

INFORMED CONSENT

Oral consent was granted by the child’s mother for the photographs taken to be used for scientific and pedagogical purposes. We have purposefully removed the name of the town and of the hospital in Guinea so as to remove any potential identifiers from this case report.

GUARANTOR

Beatriz Valle del Barrio.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wojnarowska F, Marsden RA, Bhogal B, Black MM. Chronic bullous disease of childhood, childhood cicatricial pemphigoid, and linear IgA disease of adults. J Am Acad Dermatol 1988;19:792–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kharfi M, Khaled A, Ridha MR. Linear IgA dermatosis in Tunisian children: 31 cases. Indian J Dermatol 2011;56:153–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kharfi M, Khaled A, Karaa A, Zaraa I, Fazaa B, Kamou MR. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis: the more frequent bullous dermatosis of children. Dermatol Online J 2010;16:2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Venning VA Linear IgA disease: clinical presentation, diagnosis, and pathogenesis. Dermatol Clin 2011;29:453–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fortuna G, Marinkovich MP. Linear immunoglobulin A bullous dermatosis. Clin Dermatol 2012;30:38–50. 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bickle KM, Roark TR, HSU S. Autoimmune bullous dermatoses: a review. Am Fam Physician 2002;65 Available at: www.aafp.org/afp. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Culton DA, Diaz LA. Treatment of subepidermal immunobullous diseases. Clin Dermatol 2012;30:95–102. 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Conleth A, Egan MB, Pazderka E, Taylor MS, Meyer LS, Samowitz WS, et al. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis responsive to a gluten-free diet. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:1527–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen S, Mattei P, Fischer M, Gay JD, Milner SM, Price LA. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis. Eplasty 2013;13:ic49 Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3702236/pdf/eplasty13ic49.pdf. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chorzelski TP, Jablonska S. IgA dermatosis of childhood (chronic Bullous disease of childhood). Br J Dermatol 1979;101:535–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pulimood S, Ajithkumar K, Jacob M, George S, Chandis M. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis of childhood: treatment with dapsone and co-trimoxazole. Clin Exp Dermatol 1997;22:90–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aram H Linear IgA bullous dermatosis: successful treatment with colchicine. Arch Dermatol 1984;120:960–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]