Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) of 2009, which included pathways for FDA approval of biosimilar products, was designed to promote more affordable, expanded patient access to biologic therapies. Achieving these BPCIA goals depends on overcoming formidable barriers to biosimilar adoption. Managed care and specialty pharmacy professionals are uniquely qualified to inform initiatives to address these barriers.

OBJECTIVE:

To assess perceptions regarding strategies for overcoming barriers to biosimilar adoption among managed care and specialty pharmacy professionals by conducting a survey study.

METHODS:

Invitations to complete the online survey were emailed by the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP) to members and customers and to contacts sourced from a commercial database. In addition to questions on respondent demographics and perceptions of biosimilars, the survey listed 16 strategies for overcoming key barriers to biosimilar adoption. On a 5-point scale, participants rated their opinion on the likelihood that each strategy would have the potential to assist in achieving BPCIA goals. The survey also listed 6 barriers to biosimilar adoption. On a 5-point scale, participants rated their perceived difficulty in overcoming each barrier. The survey concluded with an open-text item that asked participants to list 3 additional strategies for overcoming biosimilar adoption barriers. Response frequencies were calculated to describe participants’ ratings of the strategies and barriers. Statistical analyses were conducted to assess whether the ratings differed among respondents grouped by work organization. For the open-text item, we conducted qualitative content analyses to categorize strategies by stakeholder groups that might take primary implementation roles.

RESULTS:

A total of 300 managed care and specialty pharmacy professionals completed the survey. There was considerable variation in the preferences, policies, and practices regarding biosimilar adoption among respondents’ work organizations. Responses to several survey items reflected positive attitudes about the safety and efficacy of biosimilars; for example, 84% agreed or strongly agreed that FDA-approved biosimilars are safe and effective for patients who switch from a reference biologic. Based on pooled percentages for ratings of likely and extremely likely to overcome barriers to biosimilar adoption, the highest-rated strategies were for prescriber education about evidence from switching studies (91%) and FDA guidance on pharmacy-level substitution of reference biologics with biosimilars (90%). The lowest-rated strategies were for requiring therapeutic drug monitoring for patients who switch to biosimilars (39%) and using quotas to incentivize providers to prescribe biosimilars (40%). For the qualitative analysis, the highest numbers of respondents’ suggested strategies indicated primary implementation roles of biosimilar manufacturers (40%), the federal government (26%), and managed care organizations (15%).

CONCLUSIONS:

Reflecting the unique knowledge, perspectives, and practices of managed care and specialty pharmacy professionals, the study findings are relevant to informing and advancing initiatives for achieving BPCIA goals.

What is already known about this subject

Consonant with goals of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) of 2009, emerging biosimilar products have the potential to reduce spending on biologic therapies and increase access to patients with indicated conditions.

Current formidable barriers to adopting biosimilars include concerns about their safety and effectiveness, uncertainties associated with evolving statutory and regulatory guidance, and potential financial disincentives related to reimbursement.

What this study adds

The findings from this survey study reflect the unique knowledge, perspectives, and practices of managed care and specialty pharmacy professionals regarding strategies for overcoming barriers to biosimilar adoption toward achieving BPCIA goals.

Survey respondents expressed largely positive attitudes toward (a) the efficacy and safety of biosimilars and (b) achieving goals of the BPCIA through many diverse strategies.

The study findings may inform the development and implementation of strategies for achieving goals of the BPCIA through initiatives in which managed care and specialty pharmacy organizations take leading roles or collaborate with other stakeholder groups.

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) of 2009 created an abbreviated U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) pathway for approving biosimilar products that have been demonstrated—through analytic, pharmacologic, and clinical studies—to be similar to or interchangeable with FDA-approved biologic reference products. The goals of the BPCIA are to stimulate price competition and thereby facilitate greater access to biologic therapies for patients with indicated conditions. Since 2015, the FDA has approved 18 biosimilar products for cancer supportive care and the treatment of cancers and immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. A recently published Rand Corporation analysis estimated that, from 2017-2026, biosimilars have the potential to reduce direct spending on biologic therapies by $54 billion.1 However, achieving the goals of reduced costs and increased patient access to needed biologic therapies depends on overcoming formidable barriers to biosimilar adoption.

A major barrier to adopting biosimilar therapies is concern among providers and patients about their safety and effectiveness.2-8 In survey studies, substantial proportions of gastroenterologists, rheumatologists, and other specialty physicians have expressed doubts about the effectiveness and safety of biosimilar products compared with reference biologics.2,3,7 Among providers, an especially formidable barrier is concern about the potential immunogenicity of biosimilar products.2,3,5,6 In addition, survey studies and editorials have indicated barriers to biosimilar adoption that are associated with uncertainties about evolving statutory and regulatory guidance, especially regarding interchangeability and pharmacy-level substitution; potential financial disincentives related to reimbursement; litigation involving disputes on patents for reference biologic products; and complex pricing and rebate issues.7-12

Managed care and specialty pharmacy professionals are pivotal stakeholders in initiatives for promoting affordable patient access to biologic therapies. Pharmacists in these settings offer well-informed perspectives on key pharmacologic and pharmacoeconomic issues that may affect biosimilar adoption. Moreover, professionals in health plans and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) have unique insights into market dynamics that may determine the extent to which new biosimilar products reduce spending on biologic therapies. Thus, studies are needed to assess the perceptions of managed care and specialty pharmacy professionals regarding strategies for overcoming barriers to biosimilar adoption and, thereby, for achieving BPCIA goals. In the context of developing a continuing education program on biosimilars, we conducted a survey study to assess these perceptions among managed care professionals working in health plans, PBMs, and specialty pharmacies.

Methods

The survey and study methods were reviewed by an independent institutional review board (Sterling IRB, Atlanta, GA), which granted exempt status. Approximately 10,000 invitations to complete the online survey were emailed by the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP) to AMCP members and customers. The invitation list also included contacts in accountable care organizations and integrated delivery networks sourced from a commercial database, which is maintained by Managed Markets Insight and Technology. A screening question identified contacts who work in the pharmaceutical industry, who were excluded from survey participation in order to ensure the study’s intended focus on perceptions of health plan, PBM, and specialty pharmacy professionals. A $100 gift card was offered as incentive for completing the survey. The sample comprised the first 300 respondents to the email invitation; this maximum limit for participation was based on the budget for the survey study and associated continuing education program. The survey was fielded October 1-19, 2018.

Survey Items and Design

The survey included 28 items, which were designed to be completed in approximately 15 minutes. The first 3 items asked participants to indicate, from closed-ended lists, the type of organization in which they work; their professional roles; and their work organizations’ preferences, policies, and practices regarding biosimilar adoption. The next 2 survey items assessed participants’ attitudes toward the safety and effectiveness of FDA-approved biosimilars. On a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement with statements about the safety and effectiveness of (a) switching patients from a reference biologic to a biosimilar product and (b) extrapolating the use of a biosimilar product that the FDA has approved for 1 indication to all other approved indications for the reference biologic.

The main part of the survey listed 16 strategies for overcoming barriers to biosimilar adoption (Table 1). Based on a review of recently published survey studies and editorials, we developed strategies to address barriers that managed care and specialty pharmacists may be positioned to address through collaborative initiatives with various stakeholder groups.3,4,7,8,10,11 The 16 strategies focus on prescribers’ concerns about the safety and effectiveness of biosimilars, including concerns about immunogenicity; limited postmarketing surveillance studies; evolving formulary policies for promoting biosimilar use; potential financial disincentives for prescribing biosimilars; suboptimal administrative processes involving prior authorization and reimbursement; uncertainties associated with evolving guidance and policies of the FDA and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS); needs for public transparency involving biosimilar and reference biologic pricing; and challenges associated with conducting interchangeability studies. For each strategy, participants rated their opinion on its likelihood of overcoming barriers to biosimilar adoption toward achieving BPCIA goals. The 5-point Likert rating scale ranged from 1 (extremely unlikely) to 5 (extremely likely).

TABLE 1.

Designated Strategies for Overcoming Barriers to Biosimilar Adoption and Achieving BPCIA Goals

|

BPCIA = Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act; FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

The survey also included a list of 6 barriers to biosimilar adoption, which we developed by reviewing the literature and considering potential roles of managed care and specialty pharmacists in initiatives for overcoming them. The barriers focus on concerns about biosimilar safety among payers, prescribers, and patients; formulary management issues; state laws and regulations related to interchangeability and substitution; and pricing and contracting issues. On a 5-point Likert scale, participants rated their perceived difficulty in overcoming each barrier (1 = not at all difficult; 5 = extremely difficult).

The survey concluded with an open-text item that asked participants to list 3 additional strategies that may offer effective solutions for overcoming barriers to biosimilar adoption toward achieving BPCIA goals.

Survey Analysis

For the entire study sample, response frequencies were calculated to describe participants’ perceptions of (a) the likelihood that the 16 designated strategies can overcome barriers to biosimilar adoption and (b) the difficulty in overcoming the 6 designated barriers. For these 22 survey items, we also conducted Kruskal-Wallis tests to assess whether the ratings differed significantly among respondents grouped by their type of work organization. P values < 0.05 were considered significant. Qualitative content analysis was performed on the additional strategies that participants suggested in response to the open-text question. Two of the coauthors independently reviewed the qualitative dataset and identified domains characterized by the primary stakeholder group that would have the foremost ability to implement the suggested strategies. The researchers discussed the domains and resolved discrepancies. Through this process, a final list of domains was developed, which we used to code and count respondents’ suggested strategies for overcoming barriers to biosimilar adoption according to the stakeholder groups that would have primary implementation roles.

Results

A total of 300 managed care and specialty pharmacy professionals completed the online survey. Table 2 describes respondents’ work organizations; professional roles; and organizational preferences, policies, and practices regarding biosimilars.

TABLE 2.

Survey Respondent Characteristics

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Work organization | |

| Managed care organization or health plan | 113 (38) |

| Pharmacy benefit manager | 67 (22) |

| Specialty pharmacy | 120 (40) |

| Professional role | |

| Pharmacy director | 86 (29) |

| Medical director | 2 (1) |

| Clinical pharmacist | 118 (39) |

| Drug utilization/formulary management | 22 (7) |

| Pharmacy and therapeutics committee member | 3 (1) |

| Account manager | 6 (2) |

| Administration, contracting, or operations | 11 (4) |

| Multiple roles | 52 (17) |

| Organization preferences, policies, and practices regarding biosimilars | |

| Organization has no established policies or preferences for biosimilars; waiting for evolving safety and efficacy evidence | 72 (24) |

| Organization has established policies and preferences favoring reference biologics due to safety and efficacy concerns about biosimilars | 32 (11) |

| Organization includes biosimilars on tiers with lower copays but does not provide access through step edits or prior authorizations | 17 (6) |

| Organization has established preferences and policies that promote biosimilars over reference biologics through formulary tiering | 61 (20) |

| Organization bases preferred agents (biosimilars or reference biologics) primarily on contracting rebates | 102 (34) |

| Other | 16 (5) |

Attitudes Toward Biosimilar Safety and Effectiveness

Among all respondents, 84% agreed or strongly agreed that switching to a biosimilar product is safe and effective for patients whose conditions are treated with reference biologics. In comparison, 54% agreed or strongly agreed that a biosimilar product approved for 1 indication is safe and effective for extrapolating to all other approved indications for the reference biologic. For these items, the percentages were similar across respondents working in health plans, PBMs, and specialty pharmacies.

Perceptions of Strategies for Overcoming Barriers to Biosimilar Adoption

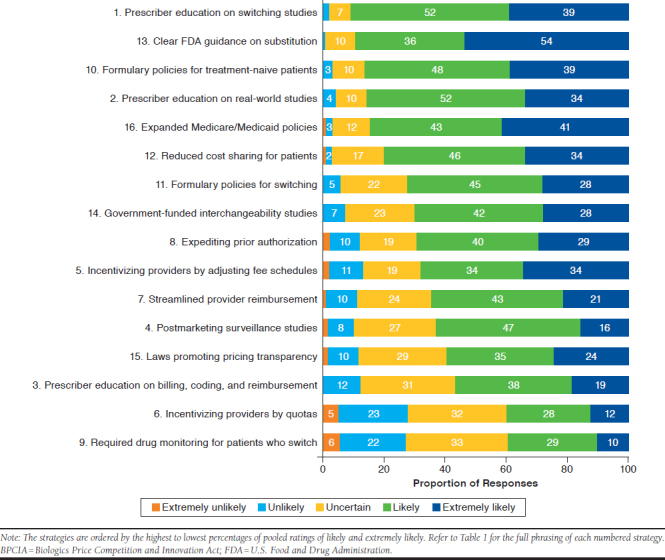

Figure 1 shows the percentages of respondent ratings of the likelihood that the 16 designated strategies can overcome barriers to biosimilar adoption toward achieving BPCIA goals. The strategies are ordered by the highest to lowest percentages of pooled Likert scale ratings of 4 (likely) and 5 (extremely likely). For example, the strategy with the highest pooled likelihood rating (91%) was “educational programs for prescribers focusing on evidence from studies in which patients switched from reference biologics to biosimilars.” The strategy with the lowest pooled likelihood rating (39%) was “requiring therapeutic drug monitoring for patients who switch to biosimilars to address concerns about immunogenicity.”

FIGURE 1.

Ratings of the Likelihood that Designated Strategies Can Overcome Barriers to Biosimilar Adoption Toward Achieving BPCIA Goals

For 13 of the 16 strategies, the likelihood ratings did not differ significantly among respondents grouped by the 3 work organizations: managed care organizations (MCOs)/health plans, PBMs, and specialty pharmacies. For the strategy involving expedited prior authorizations for biosimilars (item 8 in Table 1), the pooled percentages of likely and extremely likely ratings were significantly lower for respondents in MCOs/health plans (55%) than in PBMs (73%) and specialty pharmacies (81%; P < 0.001). For incentivizing providers by adjusting fee schedules for biosimilars (item 5 in Table 1), the pooled percentages of likely and extremely likely ratings were significantly lower for respondents in specialty pharmacies (59%) than in MCOs/health plans (74%) and PBMs (75%; P < 0.01). For requiring therapeutic drug monitoring in patients who switch to biosimilars (item 9 in Table 1), the pooled percentages of likely and extremely likely ratings were significantly lower for respondents in MCOs/health plans (32%) than in PBMs (42%) and specialty pharmacies (45%; P = 0.027).

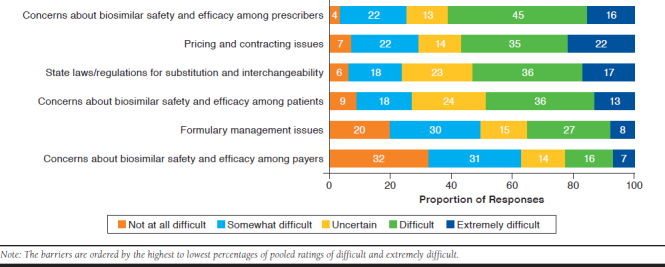

Perceptions of Difficulty in Overcoming Barriers to Biosimilar Adoption

Figure 2 shows the percentages of respondents’ ratings of difficulty in overcoming the 6 designated barriers to biosimilar adoption. The barriers are ordered by the highest to lowest percentages of pooled Likert scale ratings of 4 (difficult) and 5 (extremely difficult). The barrier with the highest pooled difficulty rating (61%) was “concerns about the safety and efficacy of biosimilars among prescribers.” The barrier with the lowest pooled difficulty rating (23%) was “concerns about the safety and efficacy of biosimilars among payers.”

FIGURE 2.

Ratings of Difficulty in Overcoming Designated Barriers to Biosimilar Adoption

For 4 of the 6 barriers, the difficulty ratings did not differ significantly among respondents grouped by the 3 work organizations. For the barrier involving concerns about the safety and efficacy of biosimilars among payers, the pooled percentages of difficult and extremely difficult ratings were significantly higher for respondents in specialty pharmacies (35%) than in MCOs/health plans (12%) and PBMs (19%; P < 0.001). For formulary management issues, the pooled percentages of difficult and extremely difficult ratings were significantly higher for respondents in specialty pharmacies (47%) than in MCOs/health plans (27%) and PBMs (28%; P < 0.01).

Open-Text Strategies for Overcoming Barriers to Biosimilar Adoption

For the open-text survey item, a total of 132 strategies were entered by 58 respondents. Through qualitative content analysis of the suggested strategies, we identified 6 stakeholder groups that would play leading roles in implementation (Table 3). Ordered by the highest to lowest proportions of associated strategies, the stakeholder groups are commercial biosimilar manufacturers (40%), the federal government (26%), MCOs (15%), medical education providers (10%), professional associations and societies (5%), and physician practices and groups (4%).

TABLE 3.

Respondents’ Suggested Strategies for Overcoming Barriers to Biosimilar Adoption Organized by Primary Stakeholder Groups for Implementation

| Primary Stakeholder Group | Strategies Associated with Each Stakeholder, n (%) | Example Verbatim Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial manufacturers | 53 (40) |

|

| Federal government | 34 (26) |

|

| Managed care | 20 (15) |

|

| Medical education providers (e.g., medical education companies, academic organizations, and medical affairs entities) | 13 (10) |

|

| Professional associations and societies | 7 (5) |

|

| Physician practices and groups | 5 (4) |

|

Note: In response to the open-text survey question, 58 respondents entered at least 1 strategy; this analysis is based on the total of 132 strategies. For the example strategies, the authors added bracketed text for clarity.

ACR = American College of Rheumatology; AWP = average wholesale price; CMS = Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; EMR = electronic medical record; FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; KOL = key opinion leader; PBM = pharmacy benefit manager.

Discussion

Formidable barriers to biosimilar adoption have been identified and discussed extensively in the literature.2-8 However, studies are lacking to identify actionable strategies for overcoming these barriers, specifically strategies that may ultimately contribute to achieving BPCIA goals of stimulating price competition and thereby facilitating greater patient access to indicated biologic therapies. This survey study is unique in its focus on assessing perceptions of such strategies among managed care and specialty pharmacy professionals.

The survey findings indicate considerable variation in the preferences, policies, and practices regarding biosimilar adoption among respondents’ work organizations. Slightly more than one third of respondents reported that their organizations base preferences for biosimilars and reference biologics primarily on contracting rebates. This approach may reflect some initial progress toward achieving the BPCIA goal of stimulating price competition. However, nearly one fourth of respondents reported that their organizations have not established policies and preferences for biosimilars because they are waiting for additional safety and efficacy evidence. This finding underscores needs for rapid and widespread dissemination of newly published evidence on biosimilar products, notably in formats that are directly applicable to the roles of managed care professionals.

Respondents expressed largely positive attitudes toward biosimilars, as 84% agreed or strongly agreed that FDA-approved biosimilar products are safe and effective for patients who switch from reference biologics. A smaller proportion (54%) agreed or strongly agreed that a biosimilar product approved for 1 indication is safe and effective to extrapolate to all other approved indications for its reference biologic. However, regarding the issue of safety and effectiveness in biosimilar extrapolation, a greater proportion of respondents indicated uncertainty (29%) compared with disagreement or strong disagreement (17%). The survey findings also reflect respondents’ generally positive attitudes toward achieving goals of the BPCIA through many diverse strategies for overcoming barriers to biosimilar adoption. Across the 16 designated strategies, only 3% to 28% of respondents gave ratings of extremely unlikely or unlikely for their potential to overcome barriers (Figure 1).

Two of the top 5 highest-rated strategies for overcoming barriers to biosimilar adoption were for prescriber education programs focusing on evidence from clinical switching studies and from postmarketing studies, including reports of real-world experiences and outcomes in Europe. Moreover, a substantial proportion the strategies offered in response to the open-text survey item indicated positive views about education on biosimilars, including suggestions for multimedia education for patients, academic detailing for providers, and collaborative education for providers and pharmacists.

Respondents’ perceptions of the most and least likely strategies for overcoming barriers to biosimilar adoption may reflect the unique knowledge, perceptions, practices, and biases of managed care and specialty pharmacy professionals. For example, 90% of respondents gave likely or extremely likely ratings for the strategy of “clear FDA guidance for substituting reference biologics with lower-cost biosimilars that meet requirements for interchangeability.” This finding is consonant with common perceptions and practices of pharmacists in managed care and specialty pharmacy settings who rely heavily on FDA guidance for establishing and streamlining policies. Moreover, several of the survey findings indicate positive perceptions of strategies that are in the purview of managed care practices. For example, 87% of respondents gave likely or extremely likely ratings for the strategy of “formulary policies that promote biosimilar use for treatment-naïve patients.” Only 38% of all respondents rated formulary management issues as a difficult or extremely difficult barrier to overcome. For this barrier, the unique perspectives of respondents who work in MCOs/health plans and PBMs are reflected by their significantly lower ratings of difficulty (27% and 28%, respectively) compared with respondents in specialty pharmacy organizations (47%).

The lowest-rated strategy for overcoming barriers to biosimilar adoption was “requiring therapeutic drug monitoring for patients who switch to biosimilars to address concerns about immunogenicity.” This finding may reflect respondents’ positive perceptions of the safety and efficacy of biosimilars and concerns about paying for additional testing that they might not view as essential. The relatively low likelihood rating for required therapeutic drug monitoring may also reflect a unique bias among managed care and specialty pharmacy professionals. Concerns about immunogenicity are among the main barriers to biosimilar adoption reported by physicians.2,3,5,6 Data in this article underscore the importance of collaborative initiatives, involving different stakeholder groups, in developing and implementing strategies for overcoming barriers to biosimilar adoption to achieve BPCIA goals.13

We did not expect the relatively low percentage of respondents (63%) who indicated that postmarketing surveillance and pharmacovigilance initiatives are likely or extremely likely to overcome barriers to biosimilar adoption. This finding might be related to respondents’ positive perceptions on the safety and efficacy of biosimilars. Like therapeutic drug monitoring, however, it is possible that the strategy of postmarketing surveillance and pharmacovigilance would be rated higher by physicians and patients.

For the qualitative content analysis of the open-text item, we chose to categorize respondents’ suggested strategies for addressing barriers to biosimilar adoption by stakeholder groups that would have the foremost ability to lead in implementing the strategies. This decision aligns with a key objective for the survey study, which is to promote calls to action and agency among relevant stakeholders. However, many of the respondents’ suggested strategies require collaboration among multiple stakeholders. An example is the strategy for “biosimilar manufacturer-funded payer-provider workshops to encourage collaboration and resolve issues.” While this strategy could be implemented by medical education providers, collaboration among multiple stakeholders—including payers, providers, and biosimilar manufacturers—would be essential for successful outcomes.

A few previous initiatives for identifying strategies to optimize biosimilar uptake, through multistakeholder forums and focus group meetings, have been reported.9,13 Participants included representatives from provider groups, MCOs, PBMs, specialty pharmacies, government agencies, consumer advocacy groups, and the pharmaceutical industry. Consonant with the strategies indicated through this survey study, participants in the previous forum and focus group initiatives identified tactics that included extending education for providers, payers, and the public; enhancing incentives and reimbursement policies for biosimilar use; streamlining contracting, billing, and reporting requirements; and implementing more comprehensive postmarketing surveillance and reporting methods regarding biosimilar therapy safety and effectiveness.9,13

Limitations

The survey participants were the first 300 respondents to the email invitation, so the findings are limited in representing the broader U.S. managed care and specialty pharmacy community. As addressed above, the findings reflect the unique knowledge, perspectives, and practices of managed care and specialty pharmacy professionals. However, potential biases related to their standard professional practices and goals may limit the implementation of the survey findings to achieve BPCIA goals, especially if multistakeholder approaches are not enacted. Another limitation involves the closed-ended design of the survey items, which precluded assessments of respondents’ underlying reasons for their perceptions and ratings. Given the marked complexity of barriers to biosimilar adoption and strategies for overcoming them, future studies that incorporate qualitative methods, including interviews with members of key stakeholder groups, would address this limitation.

Conclusions

Reflecting the unique knowledge, perspectives, and practices of managed care and specialty pharmacy professionals, the findings from this survey study are relevant to informing and advancing initiatives for achieving key goals of the BPCIA by overcoming current barriers to biosimilar adoption. The findings indicate respondents’ largely positive views on the viability of numerous and diverse strategies. Thus, first steps to applying the findings may involve discussions and deliberations about which strategies are best aligned with an organization’s goals and capabilities. In addition, plans for enacting specific strategies should consider optimal partnerships among key stakeholder groups and initiatives of professional societies and government agencies. Examples of recent initiatives include the AMCP Biologics & Biosimilars Collective Intelligence Consortium; the FDA Biosimilar Action Plan; CMS policy changes involving physician fee schedules and Medicare Part B coverage for biosimilars; and position statements and other guidance documents on biosimilars from medical societies including the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the American Gastroenterological Association, and the American College of Rheumatology.14-19 In the context of these initiatives, and through collaboration with other stakeholder groups, strategies advanced by the managed care and specialty pharmacy community have promising potential to achieve the goals of the BPCIA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mulcahy AW, Hlavka JP, Case SR. Biosimilar cost savings in the United States: initial experience and future potential. Rand Health Q. 2018;7(4):3. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6075809/. Accessed March 26, 2019. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leonard E, Wascovich M, Oskouei S, Gurz P, Carpenter D. Factors affecting health care provider knowledge and acceptance of biosimilar medicines: a systematic review. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019;25(1):102-12. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/full/10.18553/jmcp.2019.25.1.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen H, Beydoun D, Chien D, et al. Awareness, knowledge, and perceptions of biosimilars among specialty physicians. Adv Ther. 2017;33(12):2160-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobs I, Singh E, Sewell KL, Al-Sabbagh A, Shane LG. Patient attitudes and understanding about biosimilars: an international cross-sectional survey. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:937-48. Available at: https://www.dovepress.com/patient-attitudes-and-understanding-about-biosimilars-an-international-peer-reviewed-article-PPA. Accessed March 26, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feagan BG, Lam G, Ma C, Lichtenstein GR. Systematic review: efficacy and safety of switching patients between reference and biosimilar infliximab. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49(1):31-40. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/apt.14997. Accessed March 26, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonovas S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Danese S. Clinical development of biologicals and biosimilars—safety concerns. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2017;10(6):567-69. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17512433.2017.1293522?scroll=top&needAccess=true. Accessed March 26, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boccia R, Jacobs I, Popovian R, de Lima Lopes G Jr. Can biosimilars help achieve the goals of U.S. health care reform? Cancer Manag Res. 2017;9:197-205. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5459961/pdf/cmar-9-197.pdf. Accessed March 26, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hakim A, Ross JS. Obstacles to the adoption of biosimilars for chronic diseases. JAMA. 2017; 317(21):2163-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy . AMCP Partnership Forum: biosimilars—ready, set, launch. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(4):434-40. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/full/10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.4.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falit BP, Singh SC, Brennan TA. Biosimilar competition in the United States: statutory incentives, payers, and pharmacy benefit managers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(2):294-301. Available at: https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/pdf/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0482. Accessed March 26, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oskouei ST. Following the biosimilar breadcrumbs: when health systems and manufacturers approach forks in the road. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(12):1245-48. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/pdf/10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.12.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen BK, Yang YT, Bennett CL. Why biologics and biosimilars remain so expensive: despite two wins for biosimilars, the Supreme Court’s recent rulings do not solve fundamental barriers to competition. Drugs. 2018;78(17):1777-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manolis CH, Rajasenan K, Harwin W, McClelland S, Lopes M, Farnum C. Biosimilars: opportunities to promote optimization through payer and provider collaboration. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(9 Suppl):S3-9. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/pdf/10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.9-a.s3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy . AMCP Biologics & Biosimilars Collective Intelligence Consortium. Available at: http://www.amcp.org/BBCIC/. Accessed March 25, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.U.S. Food and Drug Administration . Biosimilars action plan: balancing innovation and competition. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/ApprovalApplications/TherapeuticBiologicApplications/Biosimilars/UCM613761.pdf. Accessed March 25, 2019.

- 16.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Part B biosimilar biological product payment and required modifiers. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Part-B-Drugs/McrPartBDrugAvgSalesPrice/Part-B-Biosimilar-Biological-Product-Payment.html. Accessed March 25 2019.

- 17.Howden CW, Lichtenstein GR. Meeting report: AGA biosimilars round-table. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(5):e1-e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyman GH, Balaban E, Diaz M, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: biosimilars in oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(12):1260-65. Available at: http://ascopubs.org/doi/pdf/10.1200/JCO.2017.77.4893. Accessed March 26, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American College of Rheumatology . ACR position statement on biosimilars. Available at: https://www.rheumatology.org/Portals/0/Files/Biosimilars-Position-Statement.pdf. Accessed March 25, 2019.