Abstract

Objectives

Competency assessment is a key component of point‐of‐care ultrasound (POCUS) training. The purpose of this study was to design a smartphone‐based standardized direct observation tool (SDOT) and to compare a faculty‐observed competency assessment at the bedside with a blinded reference standard assessment in the quality assurance (QA) review of ultrasound images.

Methods

In this prospective, observational study, an SDOT was created using SurveyMonkey containing specific scoring and evaluation items based on the Council of Emergency Medicine Residency‐Academy of Emergency Ultrasound: Consensus Document for the Emergency Ultrasound Milestone Project. Ultrasound faculty used the mobile phone–based data collection tool as an SDOT at the bedside when students, residents, and fellows were performing one of eight core POCUS examinations. Data recorded included demographic data, examination‐specific data, and overall quality measures (on a scale of 1–5, with 3 and above being defined as adequate for clinical decision making), as well as interpretation and clinical knowledge. The POCUS examination itself was recorded and uploaded to QPath, a HIPAA‐compliant ultrasound archive. Each examination was later reviewed by another faculty blinded to the result of the bedside evaluation. The agreement of examinations scored adequate (3 and above) in the two evaluation methods was the primary outcome.

Results

A total of 163 direct observation evaluations were collected from 23 EM residents (93 SDOTs [57%]), 14 students (51 SDOTs [31%]), and four fellows (19 SDOTs [12%]). The trainees were evaluated on completing cardiac (54 [33%]), focused assessment with sonography for trauma (34 [21%]), biliary (25 [15%]), aorta (18 [11%]), renal (12 [7%]), pelvis (eight [5%]), deep vein thrombosis (seven [4%]), and lung scan (5 [3%]). Overall, the number of observed agreements between bedside and QA assessments was 81 (87.1% of the observations) for evaluating the quality of images (scores 1 and 2 vs. scores 3, 4, and 5). The strength of agreement is considered to be “fair” (κ = 0.251 and 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.02–0.48). Further agreement assessment demonstrated a fair agreement for images taken by residents and students and a “perfect” agreement in images taken by fellows. Overall, a “moderate” inter‐rater agreement was found in 79.1% for the accuracy of interpretation of POCUS scan (e.g., true positive, false negative) during QA and bedside evaluation (κ = 0.48, 95% CI = 0.34–0.63). Faculty at the bedside and QA assessment reached a moderate agreement on interpretations noted by residents and students and a “good” agreement on fellows’ scans.

Conclusion

Using a bedside SDOT through a mobile SurveyMonkey platform facilitates assessment of competency in emergency ultrasound learners and correlates well with traditional competency evaluation by asynchronous weekly image review QA.

Since the introduction of point‐of‐care ultrasound (POCUS) in emergency departments (EDs), it has become an important tool for diagnosis, procedural guidance, and evaluation of response to therapy. In the 2013 Model of the Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine (EM), POCUS is described as an essential skill for emergency physicians.1 It has become part of the EM curriculum for all EM residency programs, but assessment of resident competence in POCUS can be challenging. In the first model curriculum addressing emergency ultrasound training for emergency physicians,2 performance of 150 ultrasound exams was felt to be adequate to demonstrate competency. The ACEP Emergency Ultrasound Guidelines published in 20013 and 20094 continued to emphasize a numbers‐based competency, and the 2016 guidelines turn more attention to competency assessment.5

Assessing residents’ POCUS competency is essential to make sure that trainees complete residency with a baseline of ultrasound skills and knowledge that can be further improved upon throughout their careers and has been an ongoing area of discussion in the academic POCUS community.6, 7, 8 The 2008 Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors (CORD) conference developed consensus recommendations for resident training in emergency ultrasound that included a competency assessment9 that was subsequently expanded to include a toolkit of competency assessment methods including standardized testing, self‐assessment, case logs, Web‐based learning, observed structured clinical examinations, standardized direct observation tool (SDOT), simulation scenarios, direct observation in clinical practice, and quality assurance (QA) review.10 Competency assessment of ultrasound skills is one of 23 Milestones incorporated into the Emergency Medicine Milestones project,11 yet a recent survey of EM residency programs shows a wide range of assessment tools being employed, including 16% of residency programs that do not evaluate competency in this milestone at all.12 A recent multiorganizational consensus paper calling for the revision of milestone PC12 points to the fact that a minority of residency programs assess competency in POCUS at the bedside.13 In this study we set out to create and evaluate a smartphone tool to assess EM learners’ competency in POCUS at the bedside as a real‐time mobile platform SDOT. We hypothesized that the results of this real‐time competency assessment would correlate well with the asynchronous QA review and competency assessment currently in place at our institution.

Methods

Study Design

The study is a prospective observational cohort study comparing two methods of POCUS competency assessments for emergency ultrasound trainees’ scans. In the first assessment, a mobile survey platform SDOT was used for a convenience sample of supervised scans. Data from the SDOT was collected electronically through an online, smartphone‐based SurveyMonkey platform. For the second assessment, a blinded determination of competency by a second ultrasound section faculty member was recorded in an asynchronous QA meeting, and the findings were correlated with the SDOT assessment. The study was reviewed by the university's institutional review board and determined to be exempt.

Study Setting and Population

The study took place in the ED of an urban teaching hospital with 72,000 patient visits per year, an EM residency, and an emergency ultrasound fellowship program. ED sonographer trainees include fourth‐year medical students on emergency POCUS elective, EM residents on POCUS rotation, and emergency ultrasound fellows. Trainees performed ultrasound examinations on patients in the ED, under supervision of a dedicated ultrasound faculty, as is currently standard practice for learners.

Study Protocol

Mobile‐based Digital Survey

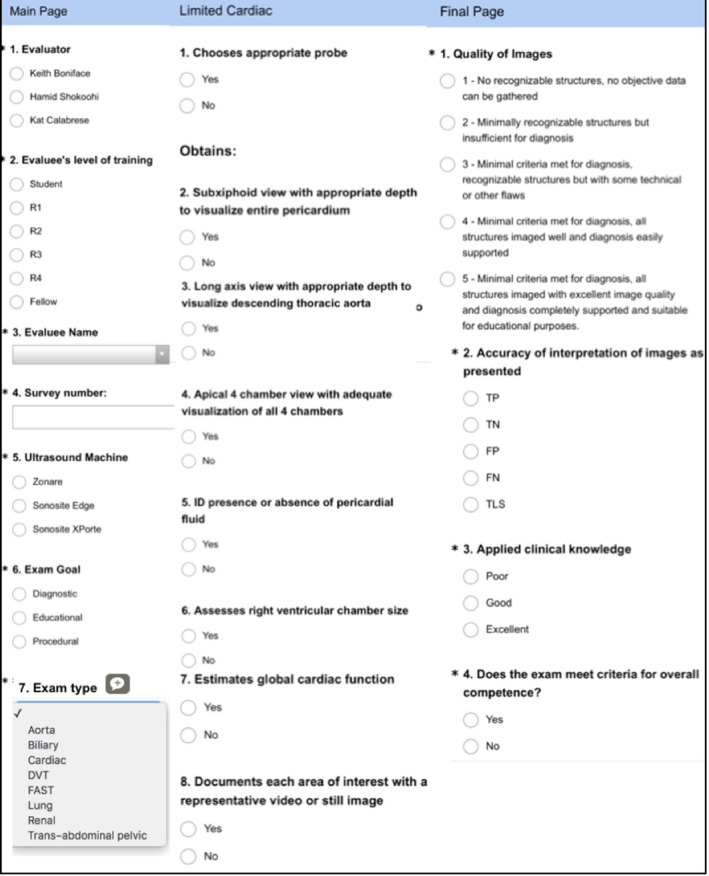

The SDOT SurveyMonkey questionnaire was composed of three sections. The first collected sonographer demographics and evaluator name, using multiple‐choice and free‐text responses, and selected examination type, which took the evaluator to the second page containing the examination‐appropriate evaluation via smart logic. This second section contained a checklist of items that sonographers should demonstrate on the ultrasound, according to the examination type being performed. This checklist was based on the SDOTs from Council of Emergency Medicine Residency–Academy of Emergency Ultrasound (CORD‐AEUS): Consensus Document for the Emergency Ultrasound Milestone Project,10 a frequently used assessment tool for POCUS in ED. The third section of the survey focused on questions related to quality of images, interpretation of images, and application of clinical knowledge based on image interpretation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Bedside SDOT. Column 1 in the figure refers to the first section of the survey instrument. Column 2 highlights the second section of the survey tool and illustrates examination‐specific questions. Column 3 is the third section of the SDOT and mirrors questions used in the QA meetings based on the CORD‐AEUS guidelines. CORD‐AEUS =Council of Emergency Medicine Residency–Academy of Emergency Ultrasound; QA = quality assurance; SDOT = standardized direct observation tool.

QA Meeting

Faculty from the ultrasound section in the department of emergency medicine gather weekly in an educational session with rotating residents, students, and ultrasound fellows to review scans that had been recorded by trainees during their ultrasound rotation or during EM clinical shifts. Image review sessions (“QA”) are a very common way of assessing competency in POCUS, with 82% of responding EM residency programs reporting use of QA as an assessment tool.12

The academic ED where this study was conducted uses Qpath (Telexy Healthcare). Qpath is a hospital server‐based, HIPAA‐compliant, password‐protected image archiver used to document and store images and interpretations of studies performed by residents and attendings as well as provide feedback on image quality to users. Using the Qpath system, evaluators can see trainee's scans and interpretations that are sent directly from the ultrasound machines in the ED and saved in the hospital server.

In this assessment, a different faculty evaluator, blinded to results from the SDOT evaluation, reviewed scans and completed the assessment of the examination‐specific goal and whether all structures and points of interest were examined under the corresponding scans. In addition, the evaluator assessed trainee image quality and interpretations on the workflow sheet on Qpath (Figure 2). E‐mail feedback was sent to trainees if there was a discrepancy on interpretation or a missed point of interest in their scans.

Figure 2.

Qpath image archival system examination dashboard with images to the left, record of interpretation in the center, and QA template on the right. QA = quality assurance.

Measurements and Data Analysis

At the time of both the SDOT and the QA session, a “quality score” was determined (Figures 1 and 2). The ability to obtain images of sufficient quality to aid in clinical decision‐making reflects competence in POCUS. Examinations were considered as adequate for diagnostic purposes for each of the two evaluation methods if the score was 3 or above (on the 5‐point scale shown in Figure 1). In addition, the ultrasound trainees’ accuracy of interpretations of the examinations was evaluated in real time at the SDOT and in retrospect during the QA sessions as true positive, true negative, false positive, false negative, or technically limited study.

Standardized direct observation tool assessment data were exported to an Excel database (Microsoft), where they were combined with data from the blinded QA session. The quality score was analyzed as a dichotomous variable, with scores of 3, 4, and 5 being defined as competent and scores of 1 and 2 defined as not competent. The inter‐rater agreement was calculated for both QA and the bedside evaluation of scans. Cohen's kappa statistic (κ) for the inter‐rater agreement was calculated. Kappa values of 0.2 to 0.4 indicated “fair” agreement, 0.4 to 0.6 “moderate” agreement, 0.6 to 0.8 “good” agreement, and greater than 0.8 “excellent” agreement. A kappa value of 1 indicated “perfect” agreement. The frequency of images with adequate quality and imaging scores were compared using chi‐square test or Student t‐test. Statistical significance was defined as a p‐value less than 0.05.

Results

A total of 165 SDOT evaluations were collected. In two cases the SDOT was incomplete; these were excluded, leaving 163 SDOTs for the final analysis. The SDOTs evaluated EM residents (93 SDOTs), medical students (51 SDOTs), and EM POCUS fellows (19 SDOTs; see Table 1 for types of POCUS examinations evaluated by SDOT. The inter‐rater agreement for the interpretation of POCUS scan (e.g., true positive, false negative) during QA and bedside evaluation was 79.1% (κ = 0.486, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.34 to 0.63) which is considered a moderate agreement. The agreement between the two methods of competency assessment with regard to image quality is fair, with agreement in 142 of 163 (87.1%) of cases. No statistically significant differences in overall number of images with high scores (3, 4, or 5) indicating adequate for image interpretation were found in bedside assessment of the quality of images when compared to the QA evaluation (92% vs. 90.1% [p = 0.31]). Considering the QA rating as the standard for this study we found no significant differences among trainees of different levels of training in acquiring adequate images (score 3, 4, or 5). The percentage of adequate images among fellows was 95%, residents 89%, and students 92% (Table 2).

Table 1.

Trainees Characteristics and the Number of SDOTs Collected

| Characteristic | All SDOTs (n = 165) |

|---|---|

| Level of training | |

| EM residents | 23 (56) |

| Medical students | 14 (34) |

| US fellows | 4 (10) |

| Completed SDOTs | |

| EM residents | 93 (57) |

| Medical students | 51 (31) |

| EM POCUS fellows | 19 (12) |

| Type of US scans | |

| Cardiac | 54 (33) |

| FAST | 34 (21) |

| Biliary | 25 (15) |

| Aorta | 18 (11) |

| Renal | 12 (7) |

| OB | 8 (5) |

| DVT | 7 (4) |

| Lung | 5 (3) |

Data are reported as n (%).

DVT = deep vein thrombosis; FAST = focused assessment with sonography for trauma; OB = obstetric; POCUS = point‐of‐care ultrasound; SDOT = standardized direct observation tool; US = ultrasound.

Table 2.

Comparing the Agreement Between Real‐time SDOT Evaluations at the Bedside and the Evaluations Performed During Image Review at QA

| Trainees (n) | Agreement, n (%) | Kappa (95% CI) | Strength of agreement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Image quality* | |||

| Overall | 142 (87.12) | 0.251 (0.02 to 0.48) | Fair |

| Fellows (19) | 19 (100) | 1.00 | Perfect |

| Residents (93) | 81 (87.10) | 0.266 (–0.03 to 0.56) | Fair |

| Students (51) | 42 (84.00) | 0.254 (–0.11 to 0.61) | Fair |

| Image interpretation | |||

| Overall | 129 (79.1) | 0.486 (0.34 to 0.63) | Moderate |

| Fellows (19) | 17 (89.47) | 0.661 (0.29 to 1.00) | Good |

| Residents (93) | 72 (77.42) | 0.412 (0.22 to 0.61) | Moderate |

| Students (51) | 40 (78.43) | 0.513 (0.27 to 0.76) | Moderate |

QA = quality assurance; SDOT = standardized direct observation tool.

Image quality was rated as 1 to 5 in which images that scored as inadequate for clinical decision making (1 and 2) were compared to the images scored as adequate for clinical decision making (3, 4, and 5).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that use of a bedside SDOT, in the form of a mobile SurveyMonkey platform linked to a paid SurveyMonkey Team Advantage account), facilitates assessment of competency in POCUS by trainees. Using this tool was straightforward, mobile, easy to implement in real time at the bedside, and facilitated the collection of evaluation data for later export and review. The smartphone platform was chosen because the smartphone is ubiquitous in EDs, the collection tool as designed was easy to use with one hand, and the interface captured a significant number of important data points for later export to spreadsheet and review. It provided an opportunity to evaluate competency in person, at the bedside, at the time of the procedure. These results provide a good foundation for continued work to standardize competency evaluations (in POCUS as well as other EM competencies) for emergency ultrasound trainees. With additional technological capabilities and mobile survey tools like SurveyMonkey and systems like Qpath, the ability to generate both portable, real‐time as well as asynchronous, retrospective evaluations has increased. This study highlights the fact that the methods used are feasible to implement, although further research is needed to develop a robust standard competency evaluation tool applicable to other training programs and to the assessment of other important EM competencies.

The SDOT assessment in this study correlated well with traditional assessment by asynchronous measures of competency determined in weekly image review QA. It is the standard in this training program for all resident scans to be reviewed in QA weekly, which absorbs approximately 4 hours of faculty time per week. Given the positive correlation between the bedside SDOT and QA assessments, any resident scans that have been functionally QA'd at the bedside using this tool could eliminate the need for reevaluation of the same scans during QA. This bedside evaluation by ultrasound faculty frees up time that can be redirected to further academic, clinical, and administrative responsibilities.

Finally, the educational benefits of timely feedback delivered to learners is well documented.14, 15 For residents enrolled in this study, the only feedback they received regarding their performance was delivered through the standard worksheet assessment in Qpath. An improvement from a feedback perspective for the residents would be to have these evaluations immediately available for their review and reflection. Timely provision of feedback has the potential to lead to behavior change on behalf of the learner, which presumably would lead to improved performance of a skill like POCUS. It also aligns well with millennial generation learners and the use of technology to facilitate learning and professional development.16

Limitations

This study has several limitations. It was conducted in a single academic center. There is also some heterogeneity of learners, which limits its applicability directly to the ACGME ultrasound milestone; however, the majority of SDOTs were recorded from residents, and this method may provide the foundation for a tool that can be developed for use in EM residencies for other skills central to the practice of EM. As POCUS is introduced earlier in medical education, it will also be important to develop a competency assessment tool which can be applied in undergraduate medical education as well. Similar to the entrustable professional activities developed by the Liason Committee on Medical Education, POCUS educators will need to keep this in mind as it relates to the evaluation portion of courses.17 Another limitation relates to the two SDOTs that were incomplete. There were some technological limitations with wireless and mobile networks communicating to the SurveyMonkey platform that may have prevented the final page of the survey from submitting. In the future, the survey tool could include specific limitations to better illustrate these challenges. In addition, some images may have demonstrated adequate views at the bedside, but the trainee's selection of views for archiving as clips may have limited the assessment of competency at the asynchronous QA session. Finally, inter‐rater agreement for the SDOT was not assessed in this study, as only one faculty member was present at the bedside for any one SDOT evaluation.

Conclusion

Bedside standardized direct observation tool assessment of point‐of‐care ultrasound competency using a mobile SurveyMonkey platform correlates well with traditional competency evaluation by asynchronous weekly image review quality assurance and provides a readily exportable record suitable for documenting experience to a trainee's portfolio.

AEM Education and Training 2019;3:172–178

Presented at the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Annual Meeting, Indianapolis, IN, May 2018.

The authors have no relevant financial information or potential conflicts to disclose.

Author contributions: KSB and HS contributed to the study concept and design; KSB, KO, MP, and HS contributed to the acquisition of the data; KSB, KO, and HS contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data; KSB, KO, AA, ML, MP, SM, and HS contributed to the drafting of the manuscript; KSB, KO, AA, ML, MP, SM, and HS contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; and KSB and HS contributed to the statistical expertise.

References

- 1. Counselman FL, Borenstein MA, Chisholm CD, et al. The 2013 Model of the Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine. Acad Emerg Med 2014;21:574–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mateer J, Plummer D, Heller M, et al. Model curriculum for physician training in emergency ultrasonography. Ann Emerg Med 1994;23:95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. American College of Emergency Physicians . Use of ultrasound imaging by emergency physicians. Ann Emerg Med 2001;38(4 Suppl):469–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. American College of Emergency Physicians . Emergency ultrasound guidelines. Ann Emerg Med 2009;53:550–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. American College of Emergency Physicians . Ultrasound guidelines: emergency, point‐of‐care and clinical ultrasound guidelines in medicine. Ann Emerg Med 2017;69:e27–e54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boniface K, Yarris LM. Emergency ultrasound: leveling the training and assessment landscape. Acad Emerg Med 2014;21:803–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stolz LA, Stolz U, Fields JM, et al. Emergency medicine resident assessment of the emergency ultrasound milestones and current training recommendations. Acad Emerg Med 2017;24:353–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Blehar DJ, Barton B, Gaspari RJ. Learning curves in emergency ultrasound education. Acad Emerg Med 2015;22:574–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Akhtar S, Theodoro D, Gaspari R, et al. Resident training in emergency ultrasound: consensus recommendations from the 2008 Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors conference. Acad Emerg Med 2009;16:S32–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lewiss RE, Pearl M, Nomura JT, et al. CORD‐AEUS: consensus document for the emergency ultrasound milestone project. Acad Emerg Med 2013;20:740–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. The Emergency Medicine Milestone Project . A Joint Initiative of The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and The American Board of Emergency Medicine. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, American Board of Emergency Medicine. The Emergency Medicine Milestone Project. 2015. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/EmergencyMedicineMilestones.pdf. Accessed September 18, 2018.

- 12. Amini R, Adhikari S, Fiorello A. Ultrasound competency assessment in emergency medicine residency programs. Acad Emerg Med 2014;21:799–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nelson M, Abdi A, Adhikari S, et al. Goal‐directed focused ultrasound milestones revised: a multiorganizational consensus. Acad Emerg Med 2016;23:1274–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ende J. Feedback in clinical medical education. JAMA 1983;250:777–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hattie J, Timperley H. The power of feedback. Rev Educ Res 2007;77:81–112. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Toohey S, Wray A, Wiechmann W, Lin M, Boysen Osborn M. Ten tips for engaging the millennial learner and moving an emergency medicine residency curriculum into the 21st century. West J Emerg Med 2016;17:337–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Englander R, Flynn T, Call S, et al. Toward defining the foundation of the MD degree: core entrustable professional activities for entering residency. Acad Med 2016;91:1352–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]