Abstract

Objective:

Cancer-related fatigue is one of the most common side effects of colorectal cancer treatment and is affected by biomedical factors. We investigated the association of inflammation- and angiogenesis-related biomarkers with cancer-related fatigue.

Methods:

Pre-surgery (baseline) serum samples were obtained from n=236 newly diagnosed colorectal cancer patients. Meso-Scale-Discovery assays were performed to measure levels of biomarkers for inflammation and angiogenesis (CRP, SAA, IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1, sICAM-1, sVCAM-1, TNFα, VEGFA, and VEGFD). Cancer-related fatigue was assessed with the EORTC QLQ-30 questionnaire at baseline and 6 and 12 months post-surgery. We tested associations using Spearman’s partial correlations and logistic regression analyses, adjusting for age, sex, and body mass index.

Results:

sICAM-1 and VEGFD showed a significant positive correlation with cancer-related fatigue at baseline and 6, and 12 month follow-up (sICAM-1: r=0.19, p=0.010; r=0.24, p=0.004; r=0.25, p=0.006; VEGFD: r=0.20, p=0.006; r=0.15, p=0.06; r=0.23, p=0.01, respectively).

Conclusion:

Biomarkers of inflammation and angiogenesis measured prior to surgery are associated with cancer-related fatigue in colorectal cancer patients throughout various time points. Our results suggest the involvement of overexpressed sICAM-1 and VEGFD in the development of fatigue.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, fatigue, inflammation, angiogenesis, biomarker

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer worldwide among men and women (Siegel et al., 2016). The number of colorectal cancer survivors has continuously increased over the past several years (Bours et al., 2016). Survivors are likely to experience deteriorating quality of life (including cancer-related fatigue) both during and after treatment periods (Bours et al., 2016). It has been reported that a healthy lifestyle, particularly physical activity, helps patients to manage the psychological and physical consequences of cancer and its treatment, such as decreasing cancer-related fatigue and increasing quality of life (Blanchard et al., 2008, Steindorf et al., 2014, Bower, 2014, Saligan et al., 2015, Filler and Saligan, 2016).

In a systematic review of 27 studies, the prevalence of cancer-related fatigue in different cancer populations ranged from 4% to 91%, and was higher in patients currently receiving cancer treatment (32% to 99%) (Lawrence et al., 2004). Cancer-related fatigue is affected by multiple factors including demographic, medical, psychological, behavioral, and biological factors, and impacts normal functioning and quality of life of patients and cancer survivors (LaVoy et al., 2016, Bower, 2014, Saligan et al., 2015, Filler and Saligan, 2016). A recent study recruited n=289 patients with localized colorectal cancer, and showed similar results with increased cancer-related fatigue during chemotherapy (70% vs. 31%) (Vardy et al., 2016). Still, the biological pathways underlying fatigue-associated symptoms in cancer patients are not completely understood (Vardy et al., 2016).

There is strong and consistent evidence linking chronic inflammatory processes to colorectal carcinogenesis (Thun et al., 2002, Ulrich et al., 2006, Iyengar et al., 2016). Inflammatory processes result in the production of reactive oxygen species that are known to damage macromolecules, including DNA (Koene et al., 2016). Through these pathways inflammation promotes malignant cell transformation and tumor progression (Koene et al., 2016). Further, the tumor itself as well as the cancer treatment (e.g., radiation, chemotherapy) have been characterized as drivers of inflammatory processes in cancer patients (Aggarwal et al., 2009, Coussens and Werb, 2002).

However, little is known about associations of inflammatory processes with quality of life and symptoms in cancer patients, particularly with cancer-related fatigue. In 2014, a systematic review summarized results of studies investigating the association between inflammation and cancer-related fatigue (Bower, 2014). Only a small number of studies in various cancer types were identified (n=8) and which were classified into three groups including fatigue (a) before treatment, (b) during treatment, and (c) after treatment (Bower, 2014). Only one study included colorectal cancer patients, in combination with esophageal and non-small cell lung cancer (Wang et al., 2012, Wang et al., 2010). This study suggested that elevated inflammatory biomarkers (e.g., IL-6) play a role in the development of fatigue and other severe symptoms during chemotherapy in colorectal cancer and esophageal cancer patients (Wang et al., 2012).

Angiogenesis-related biomarkers have been consistently associated with poor outcome of colorectal cancer patients as their pathways are essential for the growth and proliferation of colorectal cancer metastases (Mousa et al., 2015). 60%−70% of metastatic colorectal cancer patients receive treatments targeting pathways of angiogenesis-related biomarkers such as vascular-endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and epidermal growth factor (EGF) (Peeters et al., 2009). Fatigue has been observed to be a common side effect of anti-angiogenesis agents (e.g. ziv-aflibercept, regorafenib) (Van Cutsem et al., 2012, Tang et al., 2012, Lockhart et al., 2010). There has been an increasing interest in the investigation of clinical and molecular markers to identify which subgroups of colorectal cancer patients will benefit from inhibition of the angiogenesis pathways (Van Cutsem et al., 2012, Hurwitz et al., 2004, Grothey et al., 2013, Garcia-Carbonero et al., 2014).

The present study aimed to assess the association between serum concentrations of a large panel of inflammation and angiogenesis-related biomarkers, including C-reactive protein (CRP), serum-amyloid A (SAA), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-8 (IL-8), vascular-endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA), and VEGFD, TNFα, monocyte-chemotactic potein-1 (MCP-1), soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (sICAM-1), soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (sVCAM-1), prior to surgery with cancer-related fatigue before and after surgery. The selection of biomarkers covers the central markers of inflammation and angiogenesis. Some have been previously associated with cancer-related fatigue in other than colorectal cancer types (CRP, SAA, IL-6, IL-8, TNFα, sICAM-1) or have not yet been studied (VEGFD, VEGFA, MCP-1, sVCAM-1). While the association between inflammation and colorectal cancer has been well examined, its involvement in cancer-related fatigue in colorectal cancer patients is unclear. Thus, this investigation is an important approach to improve possible preventive strategies for cancer-related fatigue among the increasing number of colorectal cancer survivors.

METHODS

Study Population

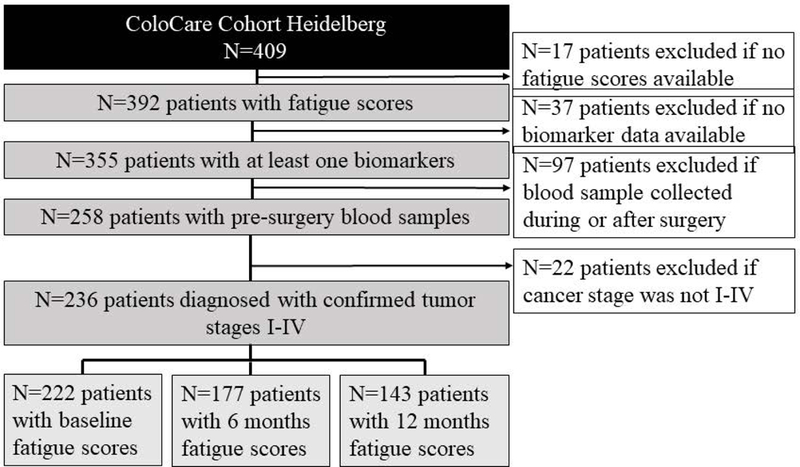

The present study is conducted as part of the prospective ColoCare study (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02328677), an international cohort of newly diagnosed stage I–IV colorectal cancer patients (ICD-10 C18–C20). The ColoCare Consortium is a multicenter initiative of interdisciplinary research on colorectal cancer outcomes and prognosis and comprises patients recruited at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle (Washington, USA), the National Center for Tumor Diseases (NCT), Heidelberg (Germany), the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa (Florida, USA), the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles (CA, USA), the St. Louis University Cancer Center, St. Louis (MO, USA), and the Huntsman Cancer Institute, Salt Lake City (Utah, USA). ColoCare inclusion criteria are: patients first diagnosed with colon or rectal cancer (stages I–IV), age ≥18 years, English (U.S. sites) or German (German site) speaking, and mentally/physically able to consent and participate. Subjects meeting the inclusion criteria are recruited for the ColoCare study prior to tumor surgery. Baseline examination includes anthropometric measurements, biospecimens collection (blood, stool, urine, saliva, and fresh frozen tissue), and self-administered questionnaires on symptoms, health behaviors, and health-related quality of life. Subjects are followed up (1) passively by retrieving medical data from hospital records, and (2) actively at 3, 6, 12, 24, and 36 months after surgery with collection of blood, stool, urine, saliva and questionnaires on symptoms, health behaviors, health-related quality of life, and dietary assessment by food frequency questionnaire. All analyses in this manuscript are based on data collected between 2010 and 2014 at the ColoCare site in Heidelberg, Germany. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Heidelberg and the institutional review board of the University of Utah, and all subjects provided written informed consent. Out of n=392 patients who had data on cancer-related fatigue available, n=355 patients had data on at least one biomarker. Patients were excluded if their blood sample was not collected pre-surgery (n=97) and if they were not classified with colorectal cancer stage I-IV (n=22). In total, n=236 men and women were included in this study. Out of those, n=222 had baseline, n=177 had 6 months, and n=143 had 12 months data on fatigue scores available. The selection of the study population is visualized in Figure 1. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Heidelberg, and all subjects provided written informed consent.

Figure 1:

Study population selection process.

Blood processing and biomarker assays

Non-fasting blood samples were collected from patients prior to surgery (baseline time point) at the University Clinic of Heidelberg. Serum was extracted within four hours after blood-draw and stored in aliquots at −80ºC until analysis. 500μl of each patient’s serum was shipped on dry ice to Huntsman Cancer Institute (HCI, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA) for analysis.

Assays for multiplexed CRP, SAA, Il-6, IL-8, sICAM-1, sVCAM-1, TNF-α, VEGFD, and VEGFA have previously been established on the Mesoscale Discovery Platform (MSD, Rockville, MD, USA) in the Ulrich laboratory at HCI. For this study blinded patient samples plus intraplate and interplate quality control samples (QC) were assayed for MCP-1, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α on the U-PLEX Proinflammatory Combo 1, for CRP, SAA, sICAM-1 and sVCAM-1 on the V-PLEX Vascular Injury Plate 2, and for VEGFA and VEGFD on the V-PLEX Angiogenesis Panel 1. The assays were ran on the Sector 2400A (MSD, Rockville, MD, USA). Blinded serum samples were ran at dilutions of 1:2 (proinflammatory), 1:1000 (vascular), and 1:8 (angiogenesis) and the serum was freeze-thawed once for the Vascular Injury and Angiogenesis panels and twice for the proinflammatory panel. A MSD sector 2100A was used to read the plates and the data was analyzed using MSD Discovery Workbench 4.0 software (both from Meso Scale Diagnostics, Rockville, MD). The overall inter-plate coefficient of variability (CV) was 9.9% and intra-plate CV was 4.6%. Studies also reported that a single measure accurately captures the short-term variability of most of the analyzed biomarkers also in long-time stored samples (Navarro et al., 2012, Hardikar et al., 2014, Ockene et al., 2001, Lee et al., 2007, Clendenen et al., 2010).

Fatigue Score

Fatigue scores were measured based on the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QLQ-C30 questionnaire at baseline and 6, and 12 month follow-up. The EORTC QLQ-C30 is a validated health-related quality of life (HRQOL) instrument, and it includes a three-item fatigue subscale (Knobel et al., 2003). This fatigue score measures primarily physical fatigue.(Knobel et al., 2003) The fatigue score asks for fatigue symptoms during the past week: ‘Did you need to rest?’, ‘Have you felt weak?’, ‘Were you tired?’ (Knobel et al., 2003). The responses are scored by a four-point Likert scale designated as ‘1=not at all, 2= a little, 3= quite a bit, 4= very much’. Using the scoring manual of the EORTC QLQ-C30,(EORTC, 2001) patients’ fatigue scores were converted to a 0–100 scale with 100 representing the highest fatigue score (Knobel et al., 2003).

Statistical analysis

Baseline CRP, SAA, IL-6, IL-8, VEGFA, VEGFD, TNFα, MCP-1, sICAM-1, and sVCAM-1 levels, as well as cancer-related fatigue scores at baseline and 6, and 12 month follow-up were used in the primary analyses. Patients with no data of all analyzed biomarkers and/or of all fatigue scores (baseline, 6, and 12 months) were excluded from the analyses. Biomarker levels were log2-transformed to prevent heteroscedasticity. Potential confounding was investigated for age (years), sex (male, female), body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), stage (I-IV), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use prior to blood draw (yes, no), and neoadjuvant chemotherapy (yes, no). The final model included age, sex, BMI, and stage. Other potential confounders (NSAID use and neoadjuvant chemotherapy) did not alter the associations and thus, were not included in the final model.

Mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for continuous variables (age, BMI, cancer-related fatigue score, and biomarker measurements). Frequency and percentage were determined for categorical variables (tumor site, tumor stage, sex, race, NSAID use, neoadjuvant, and adjuvant chemotherapy) at all study time points. One way ANOVA was used to compare mean differences across different time points for continuous variables. To test distribution differences in categorical variables across different time points Pearson’s Chi square tests were used.

In order to investigate associations without assuming a linear dose-response between cancer-related fatigue and biomarker levels, patients were additionally categorized into three groups by tertiles of fatigue scores at each study time point (low (0–22.2), medium (22.3–44.4), and high (44.5–100)). One way ANOVA was used to compare mean differences of biomarker levels across patients classified by tertiles of fatigue score (low, medium and high) at each study time point. Spearman’s partial correlation and linear regression analyses were conducted to address the association between biomarkers and cancer-related fatigue. Mixed linear models adjusted for sex, age, BMI, and tumor stage were computed to analyze the association between baseline biomarker levels and changes of fatigue scores over time. All analyses were adjusted for sex, age, BMI, and tumor stage. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA) for Windows, version 9.4. All tests were considered statistically significant when p<0.05.

RESULTS

Table 1 summarizes the patient characteristics at each study time point. Mean age was 63 years and BMI was in the overweight range (>26 kg/m2). Patients were predominantly men (69%). The mean fatigue scores differed slightly between different time points (35.3±29.4 vs. 40.7±28.8 vs. 33.5±27.6 points, p=0.05, respectively). Over 60% of the patients reported fatigue scores of >30 at each study time point which has been shown to moderately limit the patient’s quality of life (Arraras et al., 2016).

Table 1:

Study participant characteristics at study time points

| Baseline (n=222) |

6 months (n=177) |

12 months (n=143) |

p value** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (y), mean (SD) | 63 ± 12 | 63 ± 12 | 63 ± 12 | 0.94 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 69 (31) | 57 (32) | 50 (35) | 0.74 |

| Male | 153 (69) | 120 (68) | 93 (65) | |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 26.2 ± 4.11 | 26.1 ± 3.88 | 26.3 ± 3.75 | 0.87 |

| Cancer Stage, n (%) | ||||

| I | 42 (19) | 38 (21) | 32 (22) | 0.64 |

| II | 73 (33) | 65 (37) | 54 (38) | |

| III | 60 (27) | 47 (27) | 36 (25) | |

| IV | 47 (21) | 27 (15) | 21 (15) | |

| Cancer Site, n (%) | ||||

| Colon | 99 (45) | 74 (42) | 59 (41) | 0.94 |

| Rectosigmoid | 16 (7) | 12 (7) | 9 (6) | |

| Rectum | 107 (48) | 91 (51) | 75 (52) | |

| Treatment, n (%) | ||||

| Neo-adjuvant therapy | ||||

| Yes | 79 (64) | 115 (64) | 94 (66) | 0.97 |

| No | 143 (64.4) | 115 (67.8) | 94 (65.7) | |

| Adjuvant therapy | ||||

| Yes | 84 (38) | 75 (42) | 64 (45) | 0.67 |

| No | 120 (54) | 92 (52) | 75 (52) | |

| Missing | 18 (8) | 10 (5) | 4 (3) | |

| NSAID use, previous 1 week | ||||

| Yes | 50 (23) | 36 (20) | 27 (19) | 0.85 |

| No | 172 (77) | 132 (75) | 108 (76) | |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 9 (5) | 8 (5) | |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| White | 215 (96.8) | 170 (96.0) | 138 (96.5) | 0.99 |

| Hispanic | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.7) | |

| Pacific Islander | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | 5 (2.7) | 5 (2.8) | 4 (2.8) | |

| EORTC Q30 | ||||

| Fatigue score (1–100), mean (SD) | 35.3 ± 29.4 | 40.7 ± 28.8 | 33.5 ± 27.6 | 0.06 |

ANOVA (continuous outcomes) and Pearson’s Chi-squared (categorical outcomes) p-values testing differences between time points

Abbreviations: BMI=Body mass index; NSAID= nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, SD= standard deviation

N=236 serum samples were measured. The geometric mean concentrations of biomarkers are presented in Table 2. Comparing the biomarker levels of patients receiving and not receiving neo-adjuvant chemotherapy, we did not see any significant differences.

Table 2:

Biomarker levels prior to surgery, n=232

| Biomarker (unit) |

mean ± SD, median (range) |

|---|---|

| CRP (mg/l) | 11.6 ± 20.4; 3.7 (0.2–137) |

| SAA (mg/l) | 16.8 ± 30.1; 5.8 (0.2–188) |

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | 1.9 ± 9.1; 0.6 (0.1–117) |

| IL-8 (pg/ml) | 46 ± 238; 8 (2–2941) |

| MCP-1 (pg/ml) | 185 ± 118; 166 (22–1235) |

| sICAM-1 (mg/l) | 0.48 ± 0.20; 0.43 (0.24–1.49) |

| sVCAM-1 (mg/l) | 0.63 ± 0.30; 0.56 (0.28–3.60) |

| TNFα (pg/ml) | 1.23 ± 0.63; 1.13 (0.00–4.42) |

| VEGFD (pg/ml) | 876 ± 301; 816 (226–1944) |

| VEGFA (pg/ml) | 821 ± 573; 709 (101–4045) |

Abbreviations: CRP= C reactive protein; IL6/8= Interleukin 6/8; MCP1= monocyte chemotactic protein 1; SAA= serum amyloid A; sICAM-1/ sVCAM-1= soluble intracellular cell adhesion molecules; TNFα= tumor necrosis factor alpha; VEGFA= vascular endothelial growth factor A; VEGFD= vascular endothelial growth factor D

ANOVA analyses of the differences of the mean biomarker levels between patient classified by tertiles of fatigue groups (low, medium, and high) are visualized for sICAM-1 and VEGFD in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Differences in sICAM-1 and VEGFD levels between patients classified by tertiles of fatigue scores.

(A+D) baseline, (B+E) 6 months, and (C+F) 12 months (low (0–22.2), medium (22.3–44.4), and high (44.5–100)). Box-and-whisker-plots represent data with vboxes ranging from the 25th to 75th percentile, horizontal lines (median) and diamond (mean) of sICAM-1 (mg/l) and VEGFD levels (pg/ml) measured at baseline. Whiskers span minimum to maximum observed values. P-value is calculated for the differences between the three categories (low, medium, and high)

Patients with a lower fatigue score had significantly lower sICAM-1 levels at baseline (p=0.009) and 6 (p=0.01), and 12 months (p=0.004). VEGFD levels were also significantly positive associated with higher fatigue scores at baseline (p=0.004) and 12 (p= 0.01), but not at 6 months (p=0.09).

Spearman’s partial correlation coefficients adjusted for age, sex, BMI, and tumor stage are shown in Table 3. At baseline and 6, and 12 month follow-up, we observed significant and positive correlations between fatigue scores and levels of sICAM-1 (r= 0.20, p=0.01; r= 0.27, p=0.001; r= 0.25, p= 0.005) and at baseline and 12 months for levels of VEGFD (r= 0.20, p=0.004; r= 0.24, p= 0.01), respectively. A positive trend between VEGFD and sVCAM-1 and fatigue scores at 6 month follow-up (r=0.15, p= 0.06. r= 0.15, p=0.08) was also observed. No statistically significant correlations between cancer-related fatigue and other analyzed biomarkers were observed.

Table 3:

Spearman’s Partial Correlation Coefficients (Pearson) between biomarkers at baseline and fatigue scores at baseline and 6, and 12 month follow-up, adjusted for age, BMI, gender, and stage

| Variable | CRP r (p) |

IL-6 r (p) |

IL-8 r (p) |

MCP-1 r (p) |

SAA r (p) |

sICAM-1 r (p) |

sVCAM-1 r (p) |

TNFα r (p) |

VEGFA r (p) |

VEGFD r (p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 0.09 (0.23) |

0.13 (0.07) |

−0.002 (0.97) |

0.04 (0.53) |

−0.02 (0.80) |

0.19*** (0.01) |

0.11 (0.16) |

0.12 (0.09) |

0.11 (0.12) |

0.20*** (0.006) |

| 6 months | 0.12 (0.16) |

0.06 (0.43) |

0.11 (0.16) |

0.06 (0.44) |

0.06 (0.48) |

0.24*** (0.004) |

0.14 (0.08) |

0.04 (0.64) |

−0.01 (0.90) |

0.15 (0.06) |

| 12 months | 0.13 (0.18) |

0.16 (0.06) |

0.10 (0.24) |

0.07 (0.43) |

0.08 (0.40) |

0.25*** (0.006) |

0.15 (0.12) |

0.07 (0.44) |

−0.10 (0.27) |

0.23*** (0.01) |

Abbreviations: CRP= C reactive protein; IL6/8= Interleukin 6/8; MCP1= monocyte chemotactic protein 1; SAA= serum amyloid A; sICAM-1/sVCAM-1= soluble intracellular cell adhesion molecules; TNFα= tumor necrosis factor alpha; VEGFA= vascular endothelial growth factor A; VEGFD= vascular endothelial growth factor D

≤ 0.01

Linear regression analyses (see Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 1) showed similar results for sICAM-1 (β-estimate: 11.3, 17.0, and 15.8; p=0.01, 0.001 and 0.005) and VEGFD (β-estimate: 12.3, 9.7, and 13.3; p=0.004, 0.03, and 0.01) being significantly associated with fatigue scores at baseline and 6, and 12 months post-surgery. IL-6 levels were also positive associated with fatigue scores at baseline (ß-estimate: 3.1, p=0.03).

Linear mixed model analyses showed no statistically significant associations between any biomarker levels and changes in fatigue scores over time (p>0.05).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study that investigated the association of a large comprehensive panel of inflammation- and angiogenesis-related biomarkers and cancer-related fatigue in colorectal cancer patients. We observed positive correlations between specific biomarkers and fatigue scores, particularly for the biomarkers sICAM-1 (inflammation) and VEGFD (angiogenesis), which were consistently associated across several time points. Further, IL-6 levels were significantly associated with baseline fatigue scores and sVCAM-1 levels showed a modest positive trend with fatigue scores 6 months post-surgery.

To our knowledge, there are no prior studies in colorectal cancer patients linking cancer-related fatigue to levels of either sICAM-1 or VEGFD, which were consistently associated with fatigue in our study. Our results go in hand with prior work that has identified both biomarkers as potential underlying mechanisms of cancer-related fatigue in other cancer types such as breast cancer (Wang, 2008, Bower, 2014). Signaling pathways of these biomarkers are involved in the development, progression and metastasis of colorectal cancer, and are important targets of cancer treatment (Park et al., 2015). The etiology of fatigue symptoms is a complex interplay between inflammatory, endocrinologic, immuniologic processes (Bower, 2014). Pro-inflammatory cytokines produced by the tumor itself or as response to treatment-induced tissue damages induce signaling pathways in the central nervous system. These pathways are associated with fatigue symptoms via changes in neural processes that manifest motor activity, food and water intake, social withdrawal, anhedonia, and altered cognition (Zhang et al., 2017). As endothelial adhesion molecule sICAM-1 plays a key role in cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix interactions. It may trigger neuroimmune interactions by binding and recruiting immune cells such as leukocytes, neutrophils, macrophages and lymphocytes (Elenkov et al., 2000, Shi et al., 2007). The VEGFD induces blood-brain barrier disruption including through inhibiting the expression of Occludin and Claudin-1. The disruption of the blood-brain barrier leads to neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative processes, which are suggested to be involved in the development of fatigue symptoms.

Fatigue is one of the most common side effects of VEGF-receptor inhibitors (e.g. bevacizumab, ramucirumab) (Finkelmeier et al., 2016, Yang et al., 2015, Park et al., 2015). The inhibition of VEGF receptors results in increased levels of VEGF, which may be involved in manifestation of the treatment’s side effects (Park et al., 2015). Further in vitro and in vivo investigations are needed to examine biological mechanisms to explain this observation.

There are prior data on inflammatory biomarkers as risk factors for cancer-related fatigue in a variety of cancer types such as breast, prostate cancer, and, to a limited degree, colorectal cancer (Doong et al., 2015, Holliday et al., 2016, Xiao et al., 2017, Rodrigues et al., 2016, Starkweather et al., 2017, Vardy et al., 2016). With respect to colorectal cancer, a prior study (n=80) examined the association between biomarker levels including IL-6 or TGF-α and fatigue in metastatic colorectal cancer patients (Rich et al., 2005). While TGF-α was significantly correlated with fatigue-scores (r= 0.28, p=0.018), IL-6 levels were not (Rich et al., 2005). Further, the authors suggested an interactivity between cytokine signals, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, the autonomic nervous system, and efferent pathways of superchiasmatic nucleus as potential biological mechanism (Rich et al., 2005). Another study in colorectal cancer and esophageal cancer patients confirmed these results linking IL-6 to cancer-related fatigue (p<0.0001) (Wang et al., 2012). Vardy et al. investigated the association of several inflammatory biomarkers and cancer-related fatigue in n=289 colorectal cancer patients (Vardy et al., 2016). In contrast to our study, they collected baseline blood samples post-surgery and prior to chemotherapy. Further, they did not cover angiogenesis-related biomarkers or sICAM-1. They did not observe a consistent association between inflammation-related biomarkers and fatigue over time in n=289 colorectal cancer patients.(Vardy et al., 2016) Only a weak association was observed at 6 months with several cytokines including IL-6 (ρ= −0.16 to −0.20) (Vardy et al., 2016).

The biological pathways underlying inflammation-induced fatigue in cancer patients are not completely understood. There are suggestions that the inflammation-neural-immune signaling pathway has an impact on the etiology of cancer-related fatigue (Bower, 2014). Basic research studies have shown that peripheral immune activation can cause the generation of symptoms of behavioral changes (e.g., fatigue) via alterations in neural processes in the central nervous system (Irwin and Cole, 2011). Signaling of peripheral inflammatory cytokines is implemented through direct neural activation via (i) the afferent vagus nerve, (ii) peripheral cytokines transported by carrier molecules across the blood-brain barrier, and (iii) interface with cerebral cytokine receptors and cerebral vascular endothelial cells (Irwin and Cole, 2011). Animal studies indicate that these processes lead to a collection of behavioral changes described as “behavioral sickness” (Bower, 2014), including decreased motor activity (a potential behavioral demonstration of fatigue), reduced water and food intake, withdrawnness, anhedonia, and altered cognition (Irwin and Cole, 2011, Dantzer and Kelley, 2007). Similar observations have been made in healthy individuals (Capuron et al., 2000, Kirkwood, 2002, Valentine et al., 1998), as well as cancer and hepatitis C patients (Reichenberg et al., 2001, Spath-Schwalbe et al., 1998). Injections of pharmacological doses of cytokines caused a significant increase in fatigue-related symptoms (Bower, 2014). In vivo studies on the effects of tumor-necrosis-factor-alpha (TNF-α) inhibitors have shown a reduction of fatigue symptoms underlining the strong biological correlation between inflammation and cancer-related fatigue (Monk et al., 2006, Tyring et al., 2006).

This study has several strengths and limitations. Our study represents the first investigation in colorectal cancer patients examining the association between a large panel of biomarkers related not only to inflammation, but also angiogenesis, and cancer-related fatigue. The use of sera, questionnaire data, and medical records from colorectal cancer patients enrolled in the prospective ColoCare cohort provide a well-characterized study sample to examine these associations. A limitation of the study is that biomarker measurements were only available at baseline. We also recognize that a number of statistical tests were conducted, and that some of our significant observations may be due to chance. However, the consistency in associations we observed for sICAM-1 and VEGFD across multiple time points supports a true association. Other potential confounders, such as status of anemia, malnutrition, inflammatory bowel disease, or diabetes, were not available for the patient population in this study. We do believe that our data cover factors that are suggested to have the strongest association with the measured biomarkers (exposure) and fatigue scores (outcome).

In conclusion, we observed a significant association between inflammation- (IL-6) and angiogenesis-related biomarkers (sICAM-1, VEGFD) and cancer-related fatigue consistently across several time points in colorectal cancer patients. Our results suggest that not only inflammation- but also angiogenesis-related biomarkers may be involved in the development of cancer-related fatigue in colorectal cancer patients. They contribute to the understanding of the complexity of cancer-related fatigue and may provide useful information to help develop tailored treatments to the underlying mechanisms for cancer-related fatigue. Further studies are needed to identify the underlying biological mechanisms and improve preventive strategies for colorectal cancer patients and survivors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank our collaborators on the ColoCare recruitment, particularly Hermann Brenner, Jenny Chang-Claude, and Michael Hoffmeister. We are grateful to all the study staff who have made this study possible, especially Torsten Kölsch, Susanne Jakob, Stefanie Skender, Werner Diehl, Rifraz Farook, Anett Brendel, Marita Wenzel and Renate Skatula. The authors thank Samantha Wise for the critical review of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) U01 CA206110, R01 CA207371, and R01 189184, the German Consortium of Translational Cancer Research (DKTK) and the German Cancer Research Center (Division of Preventive Oncology, C. M. Ulrich). The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the NIH under Award Number P30 CA042014. C. Himbert is supported by NIH R01 CA211705, the Stiftung LebensBlicke and Claussen-Simon Stiftung, Germany. C. Himbert, Lin T, Warby C.A., J. Ose, and C.M. Ulrich are funded by the Huntsman Cancer Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

C.M.U. has as cancer center director oversight over research funded by several pharmaceutical companies, but has not received funding directly herself.

REFERENCES

- Aggarwal BB, Vijayalekshmi RV & Sung B (2009) Targeting inflammatory pathways for prevention and therapy of cancer: short-term friend, long-term foe. Clin Cancer Res 15, 425–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arraras JI, Hernandez B, Martinez M, Cambra K, Rico M, Illarramendi JJ, Viudez A, Ibanez B, Zarandona U, Martinez E & Vera R (2016) Quality of Life in Spanish advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients: determinants of global QL and survival analyses. Springerplus 5, 836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard CM, Courneya KS & Stein K (2008) Cancer survivors’ adherence to lifestyle behavior recommendations and associations with health-related quality of life: results from the American Cancer Society’s SCS-II. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 26, 2198–2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bours MJ, Van Der Linden BW, Winkels RM, Van Duijnhoven FJ, Mols F, Van Roekel EH, Kampman E, Beijer S & Weijenberg MP (2016) Candidate Predictors of Health-Related Quality of Life of Colorectal Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review. The oncologist 21, 433–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bower JE (2014) Cancer-related fatigue--mechanisms, risk factors, and treatments. Nature reviews. Clinical oncology 11, 597–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capuron L, Ravaud A & Dantzer R (2000) Early depressive symptoms in cancer patients receiving interleukin 2 and/or interferon alfa-2b therapy. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 18, 2143–2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clendenen TV, Arslan AA, Lokshin AE, Idahl A, Hallmans G, Koenig KL, Marrangoni AM, Nolen BM, Ohlson N, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A & Lundin E (2010) Temporal reliability of cytokines and growth factors in EDTA plasma. BMC Res Notes 3, 302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coussens LM & Werb Z (2002) Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 420, 860–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R & Kelley KW (2007) Twenty years of research on cytokine-induced sickness behavior. Brain Behav Immun 21, 153–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doong SH, Dhruva A, Dunn LB, West C, Paul SM, Cooper BA, Elboim C, Abrams G, Merriman JD, Langford DJ, Leutwyler H, Baggott C, Kober K, Aouizerat BE & Miaskowski C (2015) Associations between cytokine genes and a symptom cluster of pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, and depression in patients prior to breast cancer surgery. Biol Res Nurs 17, 237–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elenkov IJ, Wilder RL, Chrousos GP & Vizi ES (2000) The sympathetic nerve--an integrative interface between two supersystems: the brain and the immune system. Pharmacological reviews 52, 595–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eortc (2001). EORTC QLQ C30 Scoring Manual. Available from: http://groups.eortc.be/qol/manuals (cited 2001).

- Filler K & Saligan LN (2016) Defining cancer-related fatigue for biomarker discovery. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer 24, 5–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelmeier F, You SJ, Waidmann O, Wolff R, Zeuzem S, Bahr O & Trojan J (2016) Bevacizumab in Combination with Chemotherapy for Colorectal Brain Metastasis. J Gastrointest Cancer 47, 82–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Carbonero R, Rivera F, Maurel J, Ayoub JP, Moore MJ, Cervantes A, Asmis TR, Schwartz JD, Nasroulah F, Ballal S & Tabernero J (2014) An open-label phase II study evaluating the safety and efficacy of ramucirumab combined with mFOLFOX-6 as first-line therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncologist 19, 350–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grothey A, Van Cutsem E, Sobrero A, Siena S, Falcone A, Ychou M, Humblet Y, Bouche O, Mineur L, Barone C, Adenis A, Tabernero J, Yoshino T, Lenz HJ, Goldberg RM, Sargent DJ, Cihon F, Cupit L, Wagner A & Laurent D (2013) Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CORRECT): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet (London, England) 381, 303–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardikar S, Song X, Kratz M, Anderson GL, Blount PL, Reid BJ, Vaughan TL & White E (2014) Intraindividual variability over time in plasma biomarkers of inflammation and effects of long-term storage. Cancer causes & control : CCC 25, 969–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holliday EB, Dieckmann NF, Mcdonald TL, Hung AY, Thomas CR Jr. & Wood LJ (2016) Relationship between fatigue, sleep quality and inflammatory cytokines during external beam radiation therapy for prostate cancer: A prospective study. Radiother Oncol 118, 105–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, Cartwright T, Hainsworth J, Heim W, Berlin J, Baron A, Griffing S, Holmgren E, Ferrara N, Fyfe G, Rogers B, Ross R & Kabbinavar F (2004) Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. The New England journal of medicine 350, 2335–2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin MR & Cole SW (2011) Reciprocal regulation of the neural and innate immune systems. Nat Rev Immunol 11, 625–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar NM, Gucalp A, Dannenberg AJ & Hudis CA (2016) Obesity and Cancer Mechanisms: Tumor Microenvironment and Inflammation. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 34, 4270–4276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood J (2002) Cancer immunotherapy: the interferon-alpha experience. Semin Oncol 29, 18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knobel H, Loge JH, Brenne E, Fayers P, Hjermstad MJ & Kaasa S (2003) The validity of EORTC QLQ-C30 fatigue scale in advanced cancer patients and cancer survivors. Palliat Med 17, 664–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koene RJ, Prizment AE, Blaes A & Konety SH (2016) Shared Risk Factors in Cardiovascular Disease and Cancer. Circulation 133, 1104–1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoy EC, Fagundes CP & Dantzer R (2016) Exercise, inflammation, and fatigue in cancer survivors. Exerc Immunol Rev 22, 82–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence DP, Kupelnick B, Miller K, Devine D & Lau J (2004) Evidence report on the occurrence, assessment, and treatment of fatigue in cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SA, Kallianpur A, Xiang YB, Wen W, Cai Q, Liu D, Fazio S, Linton MF, Zheng W & Shu XO (2007) Intra-individual variation of plasma adipokine levels and utility of single measurement of these biomarkers in population-based studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 16, 2464–2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart AC, Rothenberg ML, Dupont J, Cooper W, Chevalier P, Sternas L, Buzenet G, Koehler E, Sosman JA, Schwartz LH, Gultekin DH, Koutcher JA, Donnelly EF, Andal R, Dancy I, Spriggs DR & Tew WP (2010) Phase I study of intravenous vascular endothelial growth factor trap, aflibercept, in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 28, 207–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk JP, Phillips G, Waite R, Kuhn J, Schaaf LJ, Otterson GA, Guttridge D, Rhoades C, Shah M, Criswell T, Caligiuri MA & Villalona-Calero MA (2006) Assessment of tumor necrosis factor alpha blockade as an intervention to improve tolerability of dose-intensive chemotherapy in cancer patients. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 24, 1852–1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousa L, Salem ME & Mikhail S (2015) Biomarkers of Angiogenesis in Colorectal Cancer. Biomarkers in cancer 7, 13–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro SL, Brasky TM, Schwarz Y, Song X, Wang CY, Kristal AR, Kratz M, White E & Lampe JW (2012) Reliability of serum biomarkers of inflammation from repeated measures in healthy individuals. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 21, 1167–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ockene IS, Matthews CE, Rifai N, Ridker PM, Reed G & Stanek E (2001) Variability and classification accuracy of serial high-sensitivity C-reactive protein measurements in healthy adults. Clinical chemistry 47, 444–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park DJ, Thomas NJ, Yoon C & Yoon SS (2015) Vascular endothelial growth factor a inhibition in gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 18, 33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters M, Price T & Van Laethem JL (2009) Anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monotherapy in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: where are we today? Oncologist 14, 29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichenberg A, Yirmiya R, Schuld A, Kraus T, Haack M, Morag A & Pollmacher T (2001) Cytokine-associated emotional and cognitive disturbances in humans. Arch Gen Psychiatry 58, 445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich T, Innominato PF, Boerner J, Mormont MC, Iacobelli S, Baron B, Jasmin C & Levi F (2005) Elevated serum cytokines correlated with altered behavior, serum cortisol rhythm, and dampened 24-hour rest-activity patterns in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 11, 1757–1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues AR, Trufelli DC, Fonseca F, De Paula LC & Giglio AD (2016) Fatigue in Patients With Advanced Terminal Cancer Correlates With Inflammation, Poor Quality of Life and Sleep, and Anxiety/Depression. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 33, 942–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saligan LN, Olson K, Filler K, Larkin D, Cramp F, Yennurajalingam S, Escalante CP, Del Giglio A, Kober KM, Kamath J, Palesh O & Mustian K (2015) The biology of cancer-related fatigue: a review of the literature. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer 23, 2461–2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Q, Benderdour M, Lavigne P, Ranger P & Fernandes JC (2007) Evidence for two distinct pathways in TNFα-induced membrane and soluble forms of ICAM-1 in human osteoblast-like cells isolated from osteoarthritic patients. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 15, 300–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD & Jemal A (2016) Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin 66, 7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spath-Schwalbe E, Hansen K, Schmidt F, Schrezenmeier H, Marshall L, Burger K, Fehm HL & Born J (1998) Acute effects of recombinant human interleukin-6 on endocrine and central nervous sleep functions in healthy men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83, 1573–1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkweather A, Kelly DL, Thacker L, Wright ML, Jackson-Cook CK & Lyon DE (2017) Relationships among psychoneurological symptoms and levels of C-reactive protein over 2 years in women with early-stage breast cancer. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer 25, 167–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steindorf K, Schmidt ME, Klassen O, Ulrich CM, Oelmann J, Habermann N, Beckhove P, Owen R, Debus J, Wiskemann J & Potthoff K (2014) Randomized, controlled trial of resistance training in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant radiotherapy: results on cancer-related fatigue and quality of life. Ann Oncol 25, 2237–2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang PA, Cohen SJ, Kollmannsberger C, Bjarnason G, Virik K, Mackenzie MJ, Lourenco L, Wang L, Chen A & Moore MJ (2012) Phase II clinical and pharmacokinetic study of aflibercept in patients with previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 18, 6023–6031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thun MJ, Henley SJ & Patrono C (2002) Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as anticancer agents: mechanistic, pharmacologic, and clinical issues. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 94, 252–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyring S, Gottlieb A, Papp K, Gordon K, Leonardi C, Wang A, Lalla D, Woolley M, Jahreis A, Zitnik R, Cella D & Krishnan R (2006) Etanercept and clinical outcomes, fatigue, and depression in psoriasis: double-blind placebo-controlled randomised phase III trial. Lancet (London, England) 367, 29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich CM, Bigler J & Potter JD (2006) Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for cancer prevention: promise, perils and pharmacogenetics. Nat Rev Cancer. 6, 130–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine AD, Meyers CA, Kling MA, Richelson E & Hauser P (1998) Mood and cognitive side effects of interferon-alpha therapy. Semin Oncol 25, 39–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Cutsem E, Tabernero J, Lakomy R, Prenen H, Prausova J, Macarulla T, Ruff P, Van Hazel GA, Moiseyenko V, Ferry D, Mckendrick J, Polikoff J, Tellier A, Castan R & Allegra C (2012) Addition of aflibercept to fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan improves survival in a phase III randomized trial in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer previously treated with an oxaliplatin-based regimen. J Clin Oncol 30, 3499–3506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardy JL, Dhillon HM, Pond GR, Renton C, Dodd A, Zhang H, Clarke SJ & Tannock IF (2016) Fatigue in people with localized colorectal cancer who do and do not receive chemotherapy: a longitudinal prospective study. Ann Oncol 27, 1761–1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XS (2008) Pathophysiology of cancer-related fatigue. Clinical journal of oncology nursing 12, 11–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XS, Shi Q, Williams LA, Mao L, Cleeland CS, Komaki RR, Mobley GM & Liao Z (2010) Inflammatory cytokines are associated with the development of symptom burden in patients with NSCLC undergoing concurrent chemoradiation therapy. Brain Behav Immun 24, 968–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XS, Williams LA, Krishnan S, Liao Z, Liu P, Mao L, Shi Q, Mobley GM, Woodruff JF & Cleeland CS (2012) Serum sTNF-R1, IL-6, and the development of fatigue in patients with gastrointestinal cancer undergoing chemoradiation therapy. Brain Behav Immun 26, 699–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao C, Miller AH, Felger J, Mister D, Liu T & Torres MA (2017) Depressive symptoms and inflammation are independent risk factors of fatigue in breast cancer survivors. Psychological medicine 47, 1733–1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Yin C, Liao F, Huang Y, He W, Jiang C, Guo G, Zhang B & Xia L (2015) Bevacizumab plus chemotherapy as third- or later-line therapy in patients with heavily treated metastatic colorectal cancer. Onco Targets Ther 8, 2407–2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HT, Zhang P, Gao Y, Li CL, Wang HJ, Chen LC, Feng Y, Li RY, Li YL & Jiang CL (2017) Early VEGF inhibition attenuates blood-brain barrier disruption in ischemic rat brains by regulating the expression of MMPs. Molecular medicine reports 15, 57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.