Abstract

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) converts angiotensin I into the potent vasoconstrictor angiotensin II, which regulates blood pressure. However, ACE activity is also essential for other physiological functions, presumably through processing of peptides unrelated to angiotensin. The goal of this study was to identify novel natural substrates and products of ACE through a series of mass-spectrometric experiments. This included comparing the ACE-treated and untreated plasma peptidomes of ACE-knockout (KO) mice, validation with select synthetic peptides, and a quantitative in vivo study of ACE substrates in mice with distinct genetic ACE backgrounds. In total, 244 natural peptides were identified ex vivo as possible substrates or products of ACE, demonstrating high promiscuity of the enzyme. ACE prefers to cleave substrates with Phe or Leu at the C-terminal P2′ position and Gly in the P6 position. Pro in P1′ and Iso in P1 are typical residues in peptides that ACE does not cleave. Several of the novel ACE substrates are known to have biological activities, including a fragment of complement C3, the spasmogenic C3f, which was processed by ACE ex vivo and in vitro. Analyses with N-domain-inactive (NKO) ACE allowed clarification of domain selectivity toward substrates. The in vivo ACE-substrate concentrations in WT, transgenic ACE-KO, NKO, and CKO mice correspond well with the in vitro observations in that higher levels of the ACE substrates were observed when the processing domain was knocked out. This study highlights the vast extent of ACE promiscuity and provides a valuable platform for further investigations of ACE functionality.

Graphical Abstract

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) is best known for converting angiotensin (Ang) I to the vasopressor Ang II, a central step in the renin-angiotensin system (RAS), which is responsible for blood-pressure regulation.1 The development of ACE inhibitors has had a revolutionary impact on modern cardiovascular medicine. These drugs are now widely prescribed for hypertension, heart failure, and diabetic nephropathy.2–4

ACE is a Zn-dependent dicarboxypeptidase expressed in many tissues of the body, particularly in the pulmonary endothelium, renal epithelium, and sections of the brain and intestines.5,6 Somatic ACE has two homologous catalytically active domains designated as the N- and C domains, which are the result of a gene duplication event that probably occurred before the divergence of fish and amphibians (approximately 450 million years ago).7 In contrast, the ACE isozyme called testis ACE comprises only a single C domain. The substrate specificities of the N- and C domains overlap but are not identical.8,9

The work presented here was prompted by a growing body of evidence supporting the concept that ACE is involved in a number of physiological processes other than blood-pressure regulation. Studies with transgenic mice revealed that alterations in ACE expression induce a variety of phenotypic changes. For example, homozygous-ACE-deficient (ACE-KO) mice have anatomic and functional renal defects.10 ACE-KO mice also reveal that catalytically active testis ACE is essential for male fertility.10–12 Interesting beneficial effects for the immune system were observed following overexpression of ACE in monocytes and macrophages, whereby an enhanced immune response occurred, which conferred resistance to bacterial infections, tumors,13,14 and the progression of Alzheimer’s disease-like cognitive deterioration.15 Further, it was shown that ACE expression may impact immune responses by affecting MHC class I and class II antigen processing and presentation.16,17 Other studies evidenced involvement of ACE in the development of atherosclerotic lesions,18,19 fibrosis,20,21and obesity.22 Experiments utilizing Ang II receptor blockers or Ang II receptor knockout mice revealed that several of these effects are not exerted by Ang II.23–29 in other words, ACE activity was a critical requirement, but the phenotypic effect was not mediated by Ang II. Therefore, other biologically active substrates and products of ACE need to be considered as critical links between the enzyme and the variety of ACE-dependent biological phenomena.30

It has been known for more than 40 years that ACE is a somewhat promiscuous enzyme.31 Besides Ang I, known substrates include bradykinin, the antifibrotic peptide N-acetyl-Ser-Asp-Lys-Pro, angiotensin 1–7, angiotensin 1–9, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), substance β, neurotensin, enkephalins, the chemotactic peptide N-formyl-Leu-Phe, and even the much longer peptide amyloid 1–42.32–35 In addition to studies defining a single ACE substrate, more systematic approaches have been undertaken as well. Thus, Rioli at al. used a catalytically inactive form of the metalloendopeptidases EC3.4.24.15 and EC3.4.24.16, which are closely related to ACE, to enrich potential substrates of ACE from rat-brain-tissue homogenates. This approach resulted in the mass-spectrometric identification of 15 peptides, including the vasoactive peptide hemopressin, a fragment of the α−1 chain of hemoglobin (HBA1).36 However, prior to the study presented here, the full extent of ACE promiscuity was unknown.

In order to maximize the chance for discovery of possible substrates and products of ACE present in plasma, we used high-resolution mass spectrometry for a comparative peptidomic analysis of ACE-treated and untreated plasma from ACE-deficient (ACE-KO) mice. Theoretically, comparison of plasma peptides from ACE-inhibitor-treated and untreated WT mice could provide insight into the direct effects of ACE at the peptide level, because only one parameter, ACE activity, would be altered. However, plasma is a very complex medium. Various peptidases are present and can compete with ACE or hydrolyze other peptide bonds in the substrate sequence.37 Preliminary experiments suggested that the results of such a comparison were ambiguous, and the direct effects of ACE on the peptides was often obscured (data not shown). In order to avoid the complexity of whole plasma and interindividual differences, we elaborated an ex vivo experimental design in which preisolated ACE was applied to a substrate-rich peptide mixture purified from the plasma of ACE-KO mice. Some of the identified peptide substrates or their cleavage products may be responsible for the noncanonical physiological effects attributed to ACE activity. Furthermore, we provide information on domain specificity for the identified peptide substrates processed by ACE ex vivo. For a select number of novel ACE substrates, we report their in vivo plasma concentrations in mice with specific genetic-ACE-domain-knockout backgrounds, as well as in mice that were treated with the ACE-inhibitor ramipril. These data establish the broad range of substrates cleaved by ACE.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Mice.

The creation and characterization of ACE knockout mice were previously described.10 These animals produce essentially no somatic or testis ACE. The ACE null allele is transmitted by mating heterozygous animals, which gives both homozygous-ACE-null mice and WT controls. These mice are of a mixed C57BL/6J-129/Sv background. ACE-NKO and ACE-CKO mice were made as described.38,39 Each line contains point mutations in the catalytic region of the ACE N- or C domain that eliminate Zn binding and enzymatic activity of the mutated domain. The nonmutated ACE domain is fully catalytic’ resulting in the mice having blood pressures equivalent to WT mice. The mice were inbred to a C57BL/6J background. ACE inhibition was obtained by adding ramipril into drinking water at a concentration of 160 mg/L for 10–12 days.

Isolation of ACE.

ACE was purified from mouse lung and kidney. After tissue solubilization, ACE was isolated using an ion-exchange column followed by a lisinopril-affinity column.40 The purified ACE was identified as a single band by SDS-PAGE (Figure S-1) and found to be free of protease contamination (data not shown).

ACE-Activity Measurements.

The enzymatic activity of ACE was quantified by a colorimetric assay using the Hip-Gly-Gly substrate (Bachem) as previously described.41,42 The assessment of ACE activity was performed prior to each experiment to guard against possible enzyme degradation or deactivation. The amount of ACE added to each reaction was adjusted according to the activity measurements and kept within a range of 5.5 to 5.9 mU per reaction.

Synthetic Peptides.

The peptides with the highest fold changes and identification-probability scores were chosen for synthesis in addition to angiotensin I and C3f. Angiotensin I (DRVYIHPFHL) was purchased from Sigma. Stable-isotope-labeled angiotensin I (DRVY-I*-HPFHL [I* = I-(U13C6,15N)]) was from AnaSpec Inc. The other peptides were synthesized with and without stable-isotope labels by the City of Hope Synthetic and Biopolymer Chemistry Core facility using Fmoc-Pro-OH (U13C5,15N, AnaSpec) and are listed in Table 1. Stock solutions of 1 and 2 nmol/μL unlabeled and labeled angiotensin I were prepared by dissolving the weighed, dry peptides in LC/MS-grade water. All other peptides were dissolved in a 1:1 water/acetonitrile (ACN) mixture at a concentration of 2 nmol/μL. All stock solutions were aliquoted and stored at −80 °C. Although the rough concentrations of the peptides were calculated assuming a hypothetical 100% purity of the peptide powder, a more precise determination of each peptide’s concentration was conducted using NMR spectroscopy with 4,4-dimethyl-4-silapentane-1-sulfonic acid (DSS) as the internal standard. The experiments were carried out on a 700 MHz Bruker Ascend equipped with a TCI cryoprobe, using the Watergate (water suppression by gradient-tailored excitation) NMR pulse sequence zggpwg to improve the accuracy of peak integration.43 The recycle delay was set to 30 s, and the acquisition time was 3.1 s with 64k data points acquired. The well-separated peaks of methyl and aromatic protons from 1H NMR were used in the concentration determination through comparison of the integrated peaks with those of DSS.

Table 1.

Synthetic ACE Substrate Peptides and Their Cleavage Products As Detected by Orbitrap Mass Spectrometry

| peptide | sequenceb | isotope-labeleda |

unlabeleda |

ACE-domain specificity |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| monoisotopic mass |

observed m/z |

monoisotopic mass |

observed m/z |

|||

| fibrinogen (336–346) | WGTGSPRPGSD | 1121.5134 | 561.7644 | 1115.4999 | 558.7572 | N |

| WGTGSPRPG | 919.4544 | 460.7345 | 913.4406 | 457.7276 | ||

| hemopexin (24–35) | SPLPTANGRVAE | 1216.6444 | 609.3299 | 1210.6313 | 606.3229 | N and C |

| SPLPTANGRV | 1016.5647 | 509.2896 | 1010.5512 | 506.2829 | ||

| complement C3 (1310–1319) | RLLWENGNLL | 1233.6943 | 617.8546 | 1226.6776 | 614.3461 | N and C |

| RLLWENGN | 1007.5261 | 504.7704 | 1000.5092 | 501.2619 | ||

| RLLWEN | 836.4617 | 419.2385 | 829.4446 | 415.7296 | ||

| complement C3 (C3f,1304–1320) | SSATTFRLLWENGNLLR | 1984.0603 | 993.0374 | 1977.0432 | 989.5289 | N |

| SSATTFRLLWENGNL | 1714.8751 | 858.4448 | 1707.8580 | 854.9363 | ||

| SSATTFRLLWENG | 1487.7481 | 744.8813 | 1480.7310 | 741.3728 | ||

| SSATTFRLLWE | 1316.6838 | 659.3492 | 1309.6667 | 655.8406 | ||

| inter-a-trypsin inhibitor (22–29) | FPRSPLQL | 962.5582 | 482.2865 | 956.5445 | 479.2795 | C |

| FPRSPL | 721.4155 | 361.7148 | 715.4014 | 358.7080 | ||

| serine-protease inhibitor (22–30) | FPDGTKEMD | 1044.4466 | 523.2306 | 1038.4328 | 520.2237 | N and C |

| FPDGTKEmD | 1060.4415 | 531.2282 | 1054.4270 | 528.2207 | ||

| FPDGTKE | 798.3792 | 400.1967 | 792.3652 | 397.1899 | ||

| apo A (87–01) | FSSLMNLEEKPAPAA | 1610.8087 | 806.4123 | 1603.7916 | 802.9031 | N and C |

| FSSLMNLEEKPAP | 1468.7345 | 735.3752 | 1461.7174 | 731.8660 | ||

| FSSLmNLEEKPAPAA | 1626.8036 | 814.4090 | 1619.7865 | 810.9014 | ||

| FSSLmNLEEKPAP | 1484.7294 | 743.3726 | 1477.7132 | 739.8639 | ||

| angiotensin I | DRVYIHPFHL | 1302.6946 | 652.3547 | 1295.6768 | 432.8995* | C |

| DRVYIHPF | 1052.5516 | 527.2832 | 1045.5344 | 523.7749 | ||

Charge states: z = 2+

z = 3+.

13C–15N-labeled residues are underlined m indicates oxidized methionine.

In Vitro ACE Cleavage Assessed by MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry.

Each of the eight synthetic peptides (2 pmol/μL) was incubated with WT ACE, NKO ACE, or without ACE (only buffer was added) in 100 μL of HEPES buffer (50 mM HEPES, 300 mM NaCl, and 400 mM Na2SO4; pH 8.15) for 30 min at 37 °C on an Eppendorf Thermomixer R at 300 rpm. The enzymatic reaction was stopped by addition of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) for a final pH of <4.0. The samples were desalted and concentrated on ZipTip Pipette Tips (C18, 10 μL loading capacity, 0.6 μL bed format, EMD Millipore Corporation), eluted with 1.5 μL of 0.1% TFA/70% ACN, and spotted directly onto a MALDI-TOF-MS target plate. Matrix solution, α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA, 0.5 μL, ProteoChem), prepared by dissolving 10 mg of the pure chemical in 1 mL of 0.1% TFA/70% ACN mixture, was added immediately to each sample spot. The samples were analyzed on a Simultof 200 Combo MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer (Virgin Instruments) operated in reflectron mode, and spectra of positively charged ions were acquired at 500 laser shots per spectrum. A stock solution of peptide standards was used for instrument mass calibration. It contained bradykinin fragment 2–9, substance P, neurotensin, antioxidant peptide (PFTRNYYVRAVLHL), amyloid B protein fragments 1–28 and 12–28, and ACTH fragments 1–24 and 18–39, at a concentration of 1 pmol/μL for each peptide in 0.1% TFA.

Ex Vivo LC/MS Analysis and Identification of ACE-Processed Peptides from Mouse Plasma.

Peptide Purification from ACE-Knockout (KO) Mouse Plasma.

Plasma from five male ACE-KO mice was pooled and subjected to an organo-acidic protein precipitation. For this, 1 mL of pooled plasma was mixed with acetonitrile and then trichloroacetic acid (TCA) at a 20% final concentration for each. Following a 30 min incubation on ice, the proteins were precipitated by centrifugation for 30 min at 17 000g, at 4 °C. The supernatant, which contained the peptides, was lyophilized and resuspended in 500 μL of LC/MS-grade water. In order to obtain peptides smaller than 5000 Da, the sample was then subjected to size-exclusion-gel-filtration gravity-driven chromatography, using 1 mL spin columns with 10 μm frit pores (Mo Bi Tec) filled with 400 μL of swollen Sephadex G-25 fine gel-filtration medium (Sigma) and a 5% aqueous solution of formic acid as an eluent. The resulting peptide solution was concentrated and desalted on a C-18 solid-phase-extraction (SPE) cartridge column (OASIS HLB, Waters Corporation) by eluting with 5% formic acid in methanol followed by lyophilization.

Ex Vivo ACE Cleavage.

Assisted by sonication, lyophilized peptides were gradually dissolved in 300 μL of HEPES buffer. Stable-isotope-labeled peptide standards were added at a final concentration of 50 fmol/μL each. The peptide solution was equally divided onto three tubes and incubated in the presence of WT ACE, no ACE, or acid-inactivated ACE (the pH of the sample solution was lowered to 3 with TFA prior to addition of the enzyme) for 30 min at 37 °C in an Eppendorf Thermomixer R at 300 rpm. Nonspecific acid inactivation of ACE served as a control, because ACE was the only enzyme present during incubation. In experiments aimed to determine the catalytic-domain specificity, the peptides were incubated with purified WT ACE or NKO ACE or without ACE. The enzymatic reaction was stopped after 30 min by adding 1 μL of 50% TFA. The peptides were purified on a C-18 SPE cartridge column and lyophilized. For subsequent mass-spectrometric analysis, lyophilized peptides were reconstituted in 100 μL of 0.1% aqueous formic acid and filtered through a 0.22 μm PVDF membrane.

Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (LC/MS).

Complex peptide samples were separated by UHPLC and then analyzed by high-resolution nano-electrospray LC/MS and MS/MS analysis using an Orbitrap Fusion Tribrid Mass Spectrometer (Thermo) equipped with an EasyNano LC in positive-ion mode. Chromatographic separation of the samples was carried out in triplicate as follows: 2 μL samples were loaded onto an Acclaim PepMap 100 C18 LC trapping column (3 μm, 75 μm × 2 cm, 100 Å pores, Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a flow rate of 5 /L/min with buffer A (water containing 0.1% formic acid); then, they were separated on an EASY-Spray C18 PepMap rapid-separation LC analytical column (2 μm, 75 μm × 25 cm, 100 Å pore size, Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a flow rate of 300 nL/min. The LC gradient went from 3% buffer B (acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid) to 38% B in 40 min and then to 85% at 41 min, which was maintained until 45 min. The following MS settings were used: an acquisition time of 45 min, a positive-ion spray voltage of 2200 V, an ion-transfer-tube temperature of 275 °C, internal mass calibration using ETD reagent, and a cycle time of 0.75 s. MS1 was acquired in the orbitrap at 120 000 resolution in the m/z range 400–1600, the maximum injection time was 100 ms, the AGC target was 250 000, the S-lens RF level was set to 60, and MIPS and a 15s dynamic exclusion filter were used with a mass tolerance of ±10 ppm. MS2 spectra were acquired in the orbitrap at 30 000 resolution with quadrupole-isolation mode, a 2 Da isolation window (first mass: m/z 110), and CID activation at a collision energy of 35%. One microscan was acquired with an activation Q of 0.25; the maximum injection time was 35 ms, and the AGC target was 50 000. Ions were injected during all of the available parallelizable time.

Data acquisition was controlled with the Xcalibur 3.0 software (Thermo Scientific). Ion chromatograms were processed and aligned with Progenesis QI for proteomics (Nonlinear Dynamics, Waters). For the targeted analysis, the peptide signal profiles were filtered on the basis of the following selection criteria: a p value of <0.05 and an intersample peak-intensity fold change of >2.0. Ion signals that upon ACE treatment lost intensity were considered to represent putative ACE substrates, whereas signals that gained intensity were considered to represent putative ACE products. The samples were reanalyzed with the same method containing an inclusion list of m/z targets and their retention times. The targeted inclusion mass lists are detailed in the Supporting Information, Tables S-1 and S-2. The resulting MS and MS2 data were independently analyzed with PEAKS 8.5 and with Proteome Discoverer 2.1 for identification of peptide amino acid sequences and protein assignment. In the PEAKS software, FDRs of 4.0% for peptide-spectrum matches and 1.5% for proteins were used as refining criteria to maximize identification of ACE-processed peptides, and the validity of the supporting MS/MS spectra was inspected manually. The Proteome Discoverer output data was further visualized and validated with the Scaffold 4.0 (Proteome Software) with a peptide threshold set to 95.0% probability to initially exclude the majority of inaccurate sequences. In addition to the database-assisted peptide identification (mouse NCBInr database with parent-mass-error tolerance set to 10.0 ppm and fragment-mass-error tolerance set to 0.01 Da), de novo sequencing was carried out with PEAKS using an ALC score of ≥95% for data refinement. When substrates but no matching products were detected, MS/MS evidence for the expected products were searched manually, and the supportive MS/MS fragmentation pattern was extracted and annotated (Figure S-2). The mass-spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited at the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE44 partner repository with the data set identifier PXD010258 and 10.6019/PXD010258.

The identified ACE-substrate sequences were submitted to the WebLogo 3.545 application in FASTA format to create the sequence logo depicting the relative frequencies and chemical natures of the amino acids at each position of the ACE-substrate sequence (the list of submitted sequences can be found in List S-1). In addition, the sequence logo of ACE-noncleavable peptides was created on the basis of 680 peptides identified from the untargeted analysis and was exclusive of those identified in the targeted approach (the full lists of submitted sequences can be found in List S-2). Furthermore, the relative frequencies of residues in each position of the amino acid probability matrix of ACE-noncleavable peptides were subtracted from those of the ACE-cleavable peptides. Only positive values were used to create a new sequence logo featuring ACE-preferred residues in substrate sequences. Similarly, the positive values obtained from subtraction of the relative frequencies of residues in the amino acid probability matrix of ACE-cleavable peptides from those of the ACE-noncleavable peptides were used to create a sequence logo representing the relative presences of amino acid residues in ACE-unfavorable peptide sequences. All identified peptide sequences were submitted to the Peptide Ranker server for scoring of the peptides by their probability to be bioactive from 0 to 1; peptides with a score above 0.5 were predicted bioactive with a false-positive rate of 16%.46

In Vivo Quantification of ACE Substrates by Targeted-Triple-Quadrupole-MS Analysis.

Equal volumes of plasma from four to five male mice of each genetic background (WT; ramipril-treated WT, for specific ACE inhibition in vivo; ACE KO; ACE NKO; and ACE CKO) were pooled, resulting in four separate, genotype-specific samples of 100 μL each. Each pooled sample was acidified with 0.5 μL of 100% LC/MS-grade formic acid, and the eight isotope-labeled peptide standards were spiked into each sample at a final concentration of 50 fmol/μL each. Then, the samples were subjected to TCA protein precipitation as described above. The supernatant was lyophilized, reconstituted in 100 μL of water, and filtered through a 0.22 μm PVDF membrane. In quadruplicate 5.5 min analysis runs, 10 μL of each sample in each analysis was injected into a 6490 triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with a JetStream Ion Source and into a 1290 UHPLC system (Agilent). The source parameters of the triple-quadrupole JetStream Ion Source were a desolvation-gas temperature of 230 °C, a desolvation-gas flow rate of 13 L/min, a nebulizer pressure of 20 psi, a sheath-gas temperature of 380 °C, a sheath-gas flow rate of 12 L/min, capillary voltage of 3000 V, the iFunnel parameters of 150 V for high-pressure RF and 60 V for low pressure RF, a fragmentor voltage of 380 V, and positive polarity. The samples were chromatographically separated on a Kinetex C18 LC Column (1.7 μm, 50 × 2.1 mm, 100 Å pores, Phenomenex Inc.) maintained at 30 °C at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min with the following gradient: for 1 min, the LC flow was diverted to waste; then, from 1 to 1.2 min the concentration was increased from 0 to 10% B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile), from 1.2 to 3.2 min it was increased from 10 to 12% B, from 3.2 to 5 min it was increased from 12 to 30% B, and then from 5 to 5.2 min it was increased from 30 to 98% B. The column was washed for 0.3 min before returning to initial conditions. Buffer A was 0.1% formic acid in water. The MRM transitions of the quantified peptides with their light (L)-and heavy (H)-isotope versions were split among five acquisition-time segments, as listed in Table S-3 (dwell time of 25 ms). Calibration curves were measured for all peptides and prepared by serial dilution of the unlabeled standards in a 0.1% aqueous solution of formic acid ranging from 100 fmol/μL to 50 amol/μL peptide, in which the concentrations of the labeled peptide standards were kept constant at 50 fmol/μL. In the case of apolipoprotein A-II fragment 87–101 (FSSLMNLEEKPAPAA); C3 fragment 1310–1319 (RLLWENGNLL); and C3 fragment 1304–1320, which is C3f (SSATTFRLLWENGNLLR), peptide standards were dispersed in human plasma and purified by means of TCA precipitation, as described above for the plasma samples. Methionine-containing peptides, apolipoprotein A-II fragment 87–101 (FSSLMNLEEKPAPAA) and serine-pro-tease inhibitor A3K fragment 22–30 (FPDGTKEMD) were exposed to oxidative conditions by incubation in 3.7% H2O2 for 10 min at 37 °C to convert all methionine residues into their oxidized (sulfoxide) forms. Only the Met-sulfoxide form was measured to produce a consistent signal (concentration) response.

RESULTS

Identification of ACE Substrates and Products.

Approximately 13 000 different precursor-ion peaks were detected across the analyzed samples upon alignment of the LC/MS data sets. The untargeted MS/MS fragmentation resulted in 851 peptide-spectrum matches (PSMs). Among 2411 precursor peaks that were selected for targeted MS/MS analysis, 427 peptide-spectrum matches (PSMs) were found. Finally, 244 peptides that met the selection and refining criteria on the basis of statistical significance of the differences in peak intensities between the samples and identification probability, as described in the Experimental Section, were identified and referred to as putative products or substrates ofACE (Tables 2 and S-4). We found 168 ACE substrates and 85 products. In 36 cases, substrates and their products could be matched by asserting the known dicarboxypeptidase activity of ACE, which preferentially cleaves two amino acids from the C terminus of a substrate. The detailed list of identified possible substrates and products of ACE is presented in Table S-4, which is organized in alphabetical order by the names of the proteins the peptides originated from. The accuracy and quality of our results is supported by the method’s ability to detect the internal standards and their cleavage products (Figure S-3) as well as the identification of the expected endogenous peptides bradykinin, a fragment of kininogen, and angiotensin II, a fragment of angiotensinogen (Table 2 and Figure S-4W,X, respectively).

Table 2.

Substrates and Products of ACE in the Mouse-Plasma Peptidome

| peptidea | substrate (s) or product (p) | ACE domainb |

description and comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| VGDKTLAF | s | nd | 1,4-α-glucan-branching enzyme |

| TGARQVVTL | s | nd | 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase, peroxisomal |

| TGARQVV | p | nd | |

| AGVQHIAL | s | C | 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase |

| VGAGIPYSV | s | nd | acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase, cytosolic |

| VGAGIPY | p | C | parent-peptide-derived |

| KGAIFGGF | s | nd | alcohol dehydrogenase 1 |

| PLVGGHEGAGV | s | nd | alcohol dehydrogenase 2 (not murine) |

| AGVFTKDL | p | nd | aldehyde dehydrogenase, cytosolic 1 |

| SPLFVGKVVDPTHK | s | nd | α−1-antitrypsin |

| TQSPLFVGKVVDPTHK | s | nd | |

| PLFVGKVVDPT | p | C | |

| VGKVVDPT | p | nd | |

| PLFVGKVVDP | p | N | |

| SmPPILRFD | s | C | |

| PPASVVVGPVVVPRG | p | C | α−2-HS-glycoprotein |

| VVVGPVVVPRG | s | nd | |

| VVVGPVV | p | b | |

| VGPVVVPRG | s | nd | |

| SVESASGETLHSPKVG | p | C | |

| IGAEVYHNL | s | nd | α-enolase |

| NGVKAIFDL | s | nd | α-tocopherol-transfer protein |

| LPPHPGSPG | s | nd | amelogenin X isoform |

| DRVYIHPF | p | C | angiotensinogen |

| AGLKATIF | s | nd | |

| LQGRLSPVAEE | s | nd | apolipoprotein AI |

| VIDKASETLTAQ | s | nd | |

| SLVNFFSSLmNLEEKPAPAA | p | nd | apolipoprotein AII |

| FFSSLmNLEEKPAPAA | s | nd | |

| FSSLmNLEEKPAP | p, s | b | |

| FSSLmNLEEKP | p, s | nd | |

| FSSLmNLEE | p, s | nd | |

| FSSLmNL | s | nd | |

| AGTSLVNFF | s | C | |

| AGTSLVNF | s | C | |

| AGTSLV | p | C | de novo |

| KLLAmVALL | s | C | |

| GPDmQSLFTQY | s | nd | |

| PLVRSAGTSL | s | nd | |

| AGIFTDQL | s | C | apolipoprotein C2 |

| LTLLRGE | s | nd | |

| RGIALFQGL | s | nd | ATP-binding-cassette subfamily B member 8, mitochondrial |

| AGAAFLLL | s | nd | ATP-binding-cassette subfamily D member 3 |

| ASVILAGLGF | s | nd | ATP-binding-cassette subfamily F member 3 |

| VGTQFIRGI | s | nd | ATP-binding-cassette subfamily G member 2 |

| VGADLTHVF | s | nd | ATP-dependent (S)-NAD(P)H-hydrate dehydratase |

| KGADSLEDF | p | C | ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX3X |

| TGKDSLTL | p | C | |

| AGAYVHVV | s | nd | bax inhibitor 1 |

| QGIETHLF | s | nd | β−1-syntrophin |

| AGANFYIV | s | nd | bifunctional 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate synthase |

| LGGISLGI | s | nd | butyrophilin-like protein 1 |

| LGGISL | p | C | parent-peptide-derived |

| KGQTLVVQF | s | nd | calreticulin |

| SGIALLTNF | s | nd | carbamoyl-phosphate synthase, mitochondrial |

| SGIALLT | p, s | C | de novo |

| SGIAL | p | b | |

| YGSHTFKL | s | nd | catalase (not murine) |

| YGSHTF | p | nd | |

| KGAGAFGYF | s | C | |

| GLDGAKGDAGP | s | b | collagen-α−1 (I) chain |

| SQDGGRYY | p | nd | |

| VGAKILNV | s | nd | collagen-α−1 (XVIII) chain |

| GENGIVGPTGSVGAAGP | s | nd | collagen-α−2 (I) chain |

| SGPVGKDGRSGQPGP | s | b | |

| SSATTFRLLWENGNLLR* | s | N | complement C3 |

| SSATTFRLLWENGNL* | p, s | N | |

| SSATTFRLLWENG* | p, s | N | |

| SSATTFRLLWE* | p | N | |

| RLLWENGNLL | s | b | |

| RLLWENGN | p, s | b | |

| RLLWEN | p | b | |

| SSATTFRL | s | C | |

| SSATTFR | p | nd | |

| SATTFRL | s | nd | |

| LWENGNLLR | s | nd | |

| LWENGNLL | s | nd | |

| WENGNLLR | s | nd | |

| VYNLDPLNNLGR | s | nd | complement C4-B |

| PSVPLQPVTPLQL | s | nd | |

| SGVRVFDEL | p | nd | cryptochrome 2 (photolyase-like) |

| SKLKKTAAKRSKLKKTAAKRFKL | p | N | cysteine-rich perinuclear theca 2 |

| EDFmIQKV | s | nd | cytochrome P450 2A12 |

| SGLVSRVF | s | nd | Δ(3,5)-Δ(2,4)-dienoyl-CoA isomerase, mitochondrial |

| VPPFIQP | s | nd | Down syndrome cell-adhesion molecule |

| VPPFI | p | nd | |

| NIISI | p | C | |

| VGSRAmVL | p | C | E3 ubiquitin–protein ligase UBR2 |

| ILLGP | p | nd | |

| FSANSLGAF | s | nd | estrogen receptor |

| RGIYAYGF | s | nd | eukaryotic initiation factor 4A-II |

| DTEDKGEFLSEGGGVR | s | b | fibrinogen α |

| EDKGEFLSEGGGVR | p | nd | |

| KGEFLSEGGGVR | s | nd | |

| EFLSEGGGVR | s | nd | |

| FLSEGGGVR | s | N | |

| FLSEGGG | p | N | |

| WGTGSPRPGSD | s | nd | |

| WGTGSPRPG | p | N | |

| WGTGSPRPGS | s | nd | |

| PANPNWGVF | s | nd | |

| GLISPNFKEF | s | nd | |

| ISPNFK | p | nd | parent-peptide-derived |

| mSPVPDLVPGSFK | p | N | |

| FDNHFGL | s | nd | |

| LDISHSF | s | nd | |

| ADDDYDEPTDSLDA | p | C | fibrinogen β |

| ATLHTSTAM | s | nd | gelsolin |

| SGIAVAETF | s | nd | glucose-6-phosphatase |

| SGIAVAE | p | N | |

| VGVENVAEL | s | nd | glycogen phosphorylase, liver form |

| EGIDFYTSI | s | b | heat-shock protein Hsc70t |

| EGIDFYT | p, s | C | |

| EGLDF | p | b | de novo |

| IGGHGAEY | s | nd | hemoglobin subunit α |

| SPLPTANGRVAE | s | nd | hemopexin |

| SPLPTANGRV | p | N | |

| LPTANGRVAE | s | nd | |

| KGVGASGSF | s | C | histone H1.0 |

| AGVDALRV | p | C | inosine-5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase 2 |

| FPRSPLQL | s | nd | inter-α-trypsin inhibitor, heavy chain 3 |

| FPRSPL | p | C | |

| PSVAQYPAD | s | nd | inter-α-trypsin inhibitor, heavy chain 4 |

| SLPSVAQYPAD | s | nd | |

| mLSLPSVAQYPAD | s | nd | |

| RmLSLPSVAQYPAD | s | nd | |

| SLQPSYERm | s | nd | |

| FSLQPSYERm | s | nd | |

| SLQPSYERmLSL | s | nd | |

| SGSDFSLQPSYER | s | nd | |

| SGSDFSLQPSYERm | s | nd | |

| SDFSLQPSYERm | s | nd | |

| SLPSVAAQYPAD | s | nd | inter-α-trypsin inhibitor, heavy chain 4, isoform 1 |

| RmLSLPSVAAQYPAD | s | nd | |

| RPPGFSPFR | s | nd | kininogen 1 |

| RPPGF | p | nd | de novo |

| RPPGFSPF | s | C | |

| VGTYPQGF | s | nd | leukotriene-B4 ω-hydroxylase 3 |

| VGTYPQ | p | b | |

| IGIENIHYL | s | nd | malignant T-cell-amplified sequence |

| VGVAVYQF | s | nd | membrane progestin receptor a |

| TDFEFKEL | p | nd | MOB-kinase activator 2 |

| ESPLLFKF | s | nd | moesin |

| TGSFSQKF | s | nd | murinoglobulin 1 |

| EGIKQEHTF | s | N | |

| PRVEFDL | s | nd | |

| PRVEF | p | nd | |

| AFTPEISWSL | s | nd | |

| IGVLDIYGF | s | nd | myosin |

| IGVLD | p | C | |

| DQRLEHPL | s | nd | nesprin-1 |

| SGLAI | p | b | Niemann–Pick C1-like protein 1 |

| LLLGP | p | nd | |

| NLLSI | p | C | |

| VGVGmTKF | s | nd | nonspecific lipid-transfer protein |

| GGIFAFKV | s | nd | |

| TGSTALFm | s | C | |

| KGLLYIDSV | s | nd | pantothenate kinase 3 |

| NGIKQLLEF | s | nd | peroxisomal 2,4-dienoyl-CoA reductase |

| VGSAAQSL | s | b | peroxisomal acyl-CoA oxidase 1 |

| VGVPVALDL | s | nd | peroxisomal bifunctional enzyme |

| VGVPVAL | p | nd | |

| IGATVHEL | s | nd | phenylalanine-4-hydroxylase |

| YGAGLLSSF | s | C | |

| NGAVSLIF | s | nd | |

| NGAVSL | p | b | |

| ATAKPQYVVLVPSEVY | s | nd | |

| AVAASGPGSSFR | s | nd | |

| AVAASGPGSSF | s | nd | |

| PAMGGVAPQAL | s | nd | |

| SGTFSKTF | s | nd | |

| SGSPLPY | p | b | |

| SGLSQHTGL | s | nd | phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase α |

| LDGYISTQGASL | s | nd | plasminogen |

| AGLVFVSEA | s | b | |

| AGLVFVS | p, s | nd | |

| AGLVF | p | C | de novo |

| SGVISHEL | p | nd | plectin |

| NLISL | p | C | |

| VGGKIFTF | s | nd | poly(A) polymerase |

| GPPEPEAF | s | C | poly(U)-specific endoribonuclease |

| KFLSLKLKLP | p | b | polycomb-group RING finger protein 5 |

| ALGKFFGG | s | nd | potassium channel TASK2 |

| SLGVGLSF | s | nd | probable tRNA N6-adenosine threonylcarbamoyltransferase, mitochondrial |

| GGQRTFEF | s | nd | programmed-cell-death protein 2 |

| AGIISKQL | p | C | programmed-cell-death protein 4 |

| VGSYQRDSF | s | nd | proteasome subunit β type 1 |

| QGLRTLFLL | s | nd | protein AMBP |

| QGLRTLF | p | C | de novo |

| SGVFSKYQL | s | nd | protein disulfide-isomerase |

| SPNLKSHA | s | N | protein FAM91A1 |

| ISVLHHKLIGSILIG | p | C | protein Fer1l6 |

| RGVQVNYDL | s | nd | protein sel-1 homologue 1 |

| RGVQVNY | p | C | |

| VGALLAEKm | p | C | protein-transport protein Sec31A |

| VGALL | p | nd | |

| LAPQQALSL | s | nd | prothrombin |

| NGALFVEKF | s | nd | pyruvate carboxylase, mitochondrial |

| TGIDLHEF | s | nd | R3H-domain-containing protein 2 |

| VGALLVYDI | s | nd | Ras-related protein Rab-11A |

| VGALL | p | nd | |

| AGALALLGL | s | nd | receptor-expression-enhancing protein 6 |

| IGTLQVLGF | s | nd | receptor tyrosine-protein kinase erbB-3 |

| EGIPTYRF | s | nd | scavenger receptor class B member 1 |

| AMLKTLAL | s | nd | secreted phosphoprotein 24 |

| SAQSILFmAKVN | p | b | serine-protease inhibitor A3K |

| FPDGTKEmD | s | nd | |

| FPDGTKE | p | b | |

| YTQKAPQVSTPTLVE | p | C | serum albumin |

| KGLVLIAF | s | nd | |

| KGLVLI | p | C | de novo |

| IAFSQYLQK | s | nd | |

| STPPPGPGP | s | nd | SH3 and multiple-ankyrin-repeat-domains protein 3 |

| AGADVLQTF | s | nd | S-methylmethionine-homocysteine S-methyltransferase BHMT2 |

| TGVAVFLGV | s | nd | Sodium–potassium-transporting ATPase subunit α (not murine) |

| EDFEFPNKV | p | C | solute-carrier family 35 member F5 |

| AGVNILTSI | s | nd | solute-carrier organic-anion-transporter family member |

| AGVNILT | p | C | parent-peptide-derived |

| RGVSAEYSF | s | nd | sorting- and assembly-machinery component 50 homologue |

| RGVSAEY | p | nd | |

| RGLEmLQGF | s | nd | stimulated by retinoic acid gene 6 protein-like |

| KWRISQLVPRLLVVSLIIGGL | p | b | taste-receptor type 2 member 143 |

| QGITFVKF | s | C | thioredoxin-domain-containing protein 5 |

| AGASFTAF | s | C | TLC-domain-containing protein 2 |

| SGVGALVGL | s | nd | |

| SGVGALV | p | C | |

| AGAKLFQDF | s | nd | transcriptional regulator ATRX |

| GPAKSPYQL | s | nd | transforming-growth-factor-β-induced protein ig-h3 |

| QGVHQGTGF | s | nd | translin |

| SGAGALGL | s | nd | transmembrane protein 256 |

| SGFQSLQF | s | nd | tryptophan-2,3-dioxygenase |

| RGSQQYRAL | s | nd | tubulin β |

| RGIPNYEF | s | nd | ubiquitin-fusion-degradation-protein-1 homologue |

| AGVFmGSHF | s | nd | ubiquitin-40S ribosomal protein S27a |

| LPVPE | p | C | unnamed protein product |

| AVLKLVAF | s | nd | voltage-dependent T-type calcium-channel subunit a |

| RIARVLKLLKMA | p | C | |

| AGIIAIYGL | s | nd | V-type proton-ATPase proteolipid subunit α |

| VGLEmE | p | C | de novo |

| KAVPYPE | p | C | de novo |

| FPPQ | p | nd | de novo |

| VGTGAL | p | C | de novo |

| APSFSD | s | nd | de novo |

| LPLPL | p | C | de novo |

| PFPL | p | C | de novo |

Paired substrates and products are in bold.

Asterisks indicate synthetic peptides.

C, N, and b refer to the C-terminal ACE domain, the N-terminal ACE domain, and both ACE domains, respectively; nd indicates not determined. Further details are shown in Table S-4.

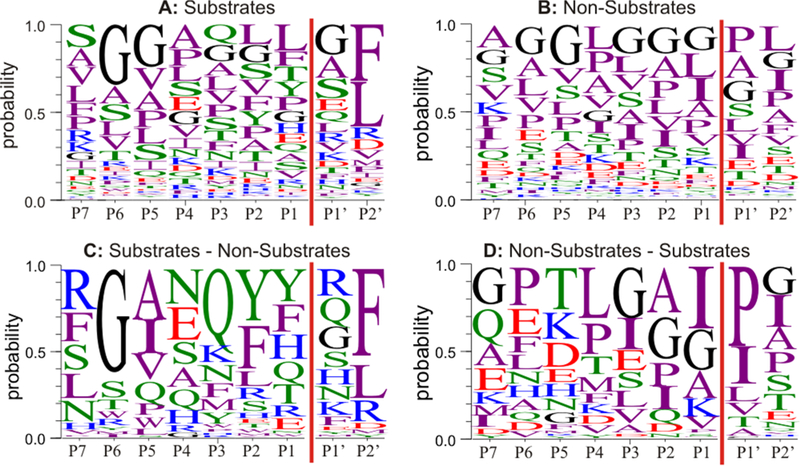

The analysis of the substrate sequences revealed enzyme preferences regarding amino acid composition around the cleavage site. The WebLogo presentation for the last nine amino acids at the C termini of ACE substrates, which includes the reputed cleavage sites between residues P1 and P1′, is shown in Figure 1A. Together with the sequence logo showing probabilities of amino acid residues in ACE-noncleavable peptides (Figure 1B), it was used to highlight the most favorable and unfavorable amino acid residues for ACE cleavage throughout the sequence, as can be seen in Figure 1C,D, respectively. The presence of phenylalanine or leucine inposition P2′ appears to be preferred by ACE as well as the presence of glycine in position P6. A predominance of polar residues after the cleavage site (positions P1–P4) also characterizes ACE substrates. Notably, proline in position P1′ as well as isoleucine in position P1 are not favorable for the enzyme.

Figure 1.

Promiscuous peptidase specificity of ACE. (A,B) Probabilities of amino acid residues around the ACE cleavage site (P1|P1′) observed in 162 substrates (A) and in 680 nonsubstrates (B). (C) Differential residue probabilities of ACE substrates minus those of nonsubstrates. (D) Differential residue probabilities at the C termini of ACE nonsubstrates minus those of substrates. Coloring scheme: polar (STYQN), green; neutral (CG), black; basic (KRH), blue; acidic (DE), red; hydrophobic (AVLIPWFM), purple.

The scores computed by the Peptide Ranker server reflecting the probabilities of the peptides to be bioactive are listed in Table S-4. Eighty-one peptides were ranked above the threshold of 0.5 and, hence, are likely to be bioactive. Among them are known bioactive peptides, such as bradykinin, angiotensin II, and C3f, which scored 0.96, 0.69, and 0.61, respectively.

Validation of ACE Cleavage and Determination of Domain Specificity.

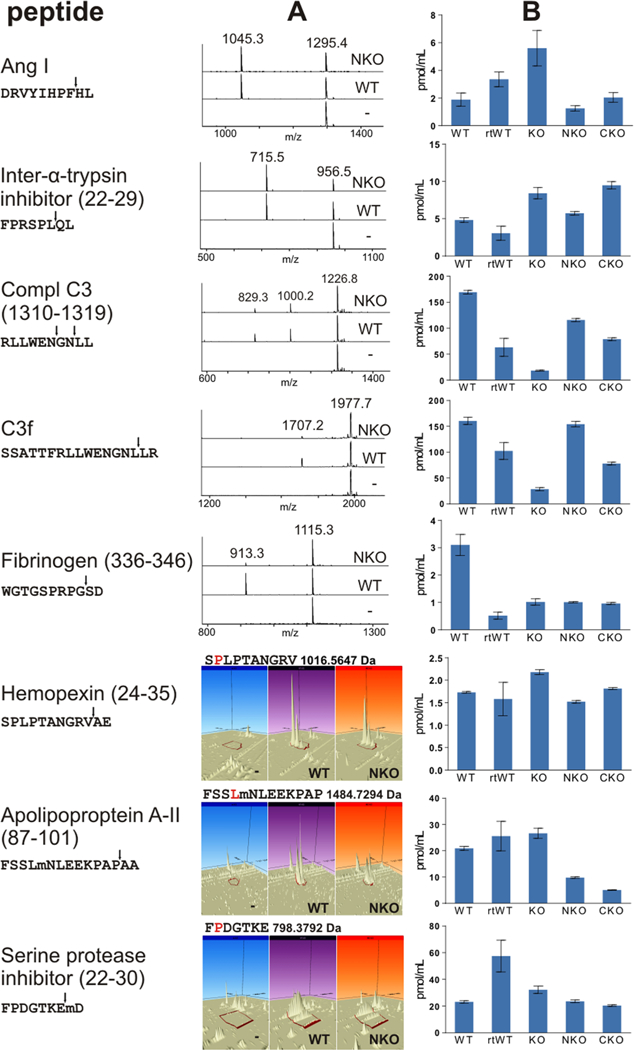

The MALDI-MS spectra (Figure 2A) demonstrate in vitro cleavage of synthetic ACE substrates by WT and NKO ACE. Angiotensin I and inter-α-trypsin-inhibitor heavy chain 3 (22–29) were preferentially cleaved by the ACE C domain, C3 (1310–1319) was cleaved by both domains, C3 (C3f, 1304–1320) and fibrinogen (336–346) were processed mostly by the N domain of ACE (Figure 2A). The cleavage products of hemopexin (24–35), apolipoprotein A-II (87–101), and serine-protease inhibitor A3K (22–30) were not detectable by MALDI-MS. Targeted MS analysis of the cleavage of labeled peptides with the a more sensitive Orbitrap LC/MS instrument revealed that hemopexin (24–35), apolipoprotein A-II (87–101), and serine-protease inhibitor A3K (22–30) were cleaved by both domains (Figure 2A). The orbitrap analysis also confirmed the domain specificity that was predetermined by MALDI-MS for the other standard peptides (Figures S-3 and 2A). In addition, some of the putative ACE substrates, identified by peptidomic LC/MS analysis, appeared to be preferentially cleaved by either one of the domains on the basis of comparisons of the substrate- or product-peak intensities detected in samples treated with WT and NKO ACE (Table 2). Representative spectra are presented in Figure S-4.

Figure 2.

Cleavage profiles of selected ACE substrates. (A) In vitro: synthetic ACE substrates treated with WT ACE, NKO ACE, or no enzyme, with the resulting peptides detected by MALDI-TOF or Orbitrap LC/MS. (B) In vivo: concentrations of endogenous ACE substrates in the blood plasma of mice with different genetic ACE backgrounds (WT, ACE KO, ACE NKO, or ACE CKO) as well as ramipril-treated WT mice (rtWT), as determined by triple-quadrupole MRM.

MRM Quantification of ACE Substrates in Vivo.

In general, higher concentrations of intact ACE substrates were measured in plasma samples of ACE-KO mice than in WT mice. However, C3 (C3f, 1304–1320), C3 (1310–1319), and fibrinogen (336–346) were exceptions to this observation. Their concentrations were markedly lower in the ACE-KO plasma samples than in the WT (Figure 2B). Plasma samples from ramipril-treated WT mice contained higher levels of angiotensin I and serine-protease inhibitor A3K (22–30), similar levels of hemopexin (24–35) and apolipoprotein A-II (87–101), and lower levels of inter-a-trypsin-inhibitor heavy chain 3 (22–29), C3 (C3f, 1304–1320), C3 (1310–1319), and fibrinogen (336–346). In all cases, except for that of fibrinogen (336–346), the ACE-domain specificity was in a good correspondence with the in vitro results. Higher levels of the ACE substrates were observed when the processing domain was knocked out.

DISCUSSION

Many endogenous peptides are known to mediate biological effects and their activities are commonly regulated by the actions of proteases and peptidases. Although proteolytic enzymes are not always substrate specific, they usually follow certain cleavage rules. Thus, ACE was noticed to activate or inactivate peptides by cleaving the last two amino acids from the C terminus. Over the years, about a dozen endogenous bioactive peptides were found to be regulated by the carboxypeptidase activity of ACE. However, especially in light of accumulated observations of ACE playing a role in diverse physiological processes, the existence of other bioactive peptides processed by ACE seems reasonable. Our robust mass-spectrometry-based approach was designed to detect as many natural substrates of ACE in plasma as possible. Given the fact that the ACE-KO-mouse-plasma peptidome should contain mostly uncleaved substrates of ACE, incubation with ACE resulted in their apparent cleavage or, in terms of mass spectrometry, in the emergence of peaks that represent cleavage products and in the disappearance or decrease in intensities of substrate peaks. The peaks of interest (i.e., those of substrates and products of ACE) were further sequenced by their MS/MS fragmentation patterns and pairwise matched by two-residue differences at the C termini.

In fact, our comprehensive mass-spectrometric analysis of the mouse-plasma peptidome revealed a variety of substrates and products of ACE. Among them, there are several bioactive endogenous peptides whose physiological levels are known to be regulated by ACE. These include bradykinin and angiotensin I and II; many other peptides were identified as novel substrates and products of ACE.

Our finding that proline in the penultimate position of the C terminus of an ACE substrate (position P1’ in the logo sequence, Figure 1D) is not favorable, is consistent with previous observations.8,33,47 Likewise, products with Pro in the P1′ position are not further cleaved by ACE and, therefore, are easily detectable, as exemplified by ACE cleavage products of fibrinogen (336–346), inter-α-trypsin-inhibitor heavy chain 3 (22–29), and Ang II itself. On the other hand, if the product sequence is not blocked by proline, it can be further cleaved by ACE and, if too short, may not be efficiently fractionated. This may also explain why there are fewer identified products than substrates. An example for such multiple ACE cleavages is the processing of complement C3 (C3f, 1304–1320) and complement C3 (1310–1319) by ACE.

Because of the complexity of plasma samples and limitations of LC/MS analyses, our ability to qualitatively identify peptides is limited and largely confined to sequencing of tryptic peptides via database-assisted identification algorithms.48 De novo sequencing with Peaks software contributed to only 14 confidently identified peptides. Also, post-translational modifications and poor fragmentation may leave gaps in the sequence coverage that are difficult to fill in using de novo sequencing or database-matching approaches, further impeding deduction of an amino acid sequence from MS2 data. Nevertheless, the targeted MS/MS analysis was more efficient than the untargeted one, resulting in sequencence identification of about 10% of the signals from peptides processed by ACE and 57% of PMSs. These identification rates are comparable to or exceed those reported by other plasma peptidomics studies.49–52

Review of the literature reveals that recent peptidomic studies were able to identify a total of 560 to 6650 peptides in human plasma using data-dependent acquisition mode.49–53 Remarkably, these identified peptides were assigned to hundreds of precursor proteins, although more than 10 000 proteins have been detected in human plasma.54 Furthermore, the majority of identified peptides are degradation products of only a few of the most abundant plasma proteins, such as complements C3 and C4, fibrinogen α and β chains, apolipoproteins, collagens, α−1-antitrypsin and others.50,51,53 Many peptides that we found to be processed by ACE in our mouse peptidomic study are also fragments of the abovementioned proteins.

Although a third of the identified ACE-processed peptides were predicted to be bioactive, particular biologic effects have been described for only few of them. Thus, series of peptides from complement C3, identified as possible substrates or products of ACE, are worth noticing. All these peptides are derivatives of C3f, a 17 amino acid long fragment buried in the C3 sequence. C3f is released in two steps during C3 degradation. First, C3 is cleaved by C3 convertases into two parts: C3a, and C3b. C3b, in turn, can activate the next complement components in the cascade or can be degraded by regulatory proteins, such as Factor I, Factor H, membranal cofactor protein (CD46), and complement receptor 1, resulting in release of C3f, as well as other fragments.55–57 Human C3f was previously reported to have physiological functions similar to those of C3a, a known anaphylatoxin and potent mediator of the inflammatory response.55 C3f was mildly spasmogenic, inducing the contraction of guinea pig ileum at micromolar concentrations. Presumably, C3f acts through the same receptors as C3a. C3f was shown to increase permeability and proliferation of microvascular endothelial cells and to cause mild smooth-muscle contractions. Its major metabolite, des-Arg-C3f,exhibited similar vascular effects.55,58 Also, C3f and its des-Arg derivatives were found at higher levels in serum samples from patients with diverse malignances than in those from control subjects.59–61 In addition, the C3f fragment HWESAS was reported as a serum-derived low-molecular-weight growth factor essential for sulfation and mitogenic activities of insulin-like growth factors (iGFs).62–64 The origin of this peptide in human serum is unknown.62 Koomen et al. detected a series of N-terminus-truncated C3f peptides, suggesting that C3f can be degraded by amino-peptidase N.65 Our data indicate that ACE cleaves the last two amino acids from the C terminus of C3f (C3 fragment 1304–1320) as well as those of its des-Arg derivative (C3 fragment 1310–1319). Together, these data suggest that HWESAS could be liberated by the joint actions of aminopeptidase N and ACE.

The in vivo levels of the ACE substrates were mostly consistent with our in vitro and ex vivo cleavage results. However, the concentrations of C3f and the des-Arg derivative (C3 fragment 1310–1319) in ACE-KO-mouse plasma were lower than in WT-mouse plasma, whereas the opposite should be expected from substrates of ACE (Figure 2). This discrepancy between in vitro and in vivo results for C3f concentrations in ACE-KO-mouse plasma is likely a consequence of the inherent kidney malfunction that ACE-KO mice bear.10 It is well-recognized that kidney malfunction is associated with enhanced activity and impaired regulation of the complement cascade, particularly the alternative complement pathway,66–72 which results in decreased C3 levels in the blood.73–76 Furthermore, reduced concentration of C3f peptide HWESAS was reported during renal failure but restored upon successful renal transplantation.62,77,78 Thus, the low C3f concentrations observed in the plasma of ACE-KO mice are likely a consequence of reduced levels of antecedent C3 or C3b,62 which dominate and obscure the effect of the lack of ACE activity. The synchronicity observed between C3f and its des-Arg derivative also advocates involvement of a common preceding effector. Consistently, C3f concentrations in plasma from NKO and CKO mice, which have normally functioning kidneys, were in accordance with our in vitro determination, by which C3f was preferably cleaved by the N domain of ACE. Notably, ACE inhibition resulted in decreased levels of C3f and its des-Arg derivative, albeit to a lesser extent than ACE deletion, suggesting these peptides are derivatives of a longer substrate of ACE. Unexpectedly, similar levels of fibrinogen (336–346) were detected in the plasma of all transgenic and ramipril-treated mice, and the levels were lower than those in WT-mouse plasma, indicating that full ACE activity is required for the generation of this peptide.

The use of NKO ACE as well as transgenic mice made it possible to determine preferences for the processing domains for many identified substrates and products of ACE. Our results confirm that angiotensin I is preferentially cleaved by the C domain of ACE, as was reported previously.39

However, in some cases, our ability to determine domain specificity was limited by a number of factors. In general, it was more difficult to define clear domain selectivity for substrates than for products of ACE. A decrease in substrate concentration as a result of the addition of ACE with one active processing domain did not always permit us to draw conclusions, whereas the emergence of an ACE-domain-specific product was typically quite obvious.

Another difficulty was determining the contribution of the N domain in cases where WT ACE and NKO ACE both efficiently cleaved the substrate. Such cases could be resolved only by application of CKO ACE or an ACE C domain specific inhibitor, which, however, were not available for this study.

In summary, at least 244 natural peptides are affected by the dicarboxypeptidase activity of ACE. ACE cleavage and domain specificity were confirmed in vitro and in vivo for a number of selected peptides. These results represent the most comprehensive evidence for the wide promiscuity of the enzyme to date. Our study resulted in the creation of a library of substrates and products of ACE, which can be further tested for their biological functions and can help us find the link between ACE and the physiological effects attributed to its activity.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Roger Moore, Teresa Hong, Weidong Hu, Yuelong Ma, and Nora Karau for their assistance. This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health under award numbers P01HL129941 and P30CA033572.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.anal-chem.8b03828.

Targeted-inclusion-mass lists, MRM transitions, detailed list of identified substrates and products of ACE, SDS-PAGE image of purified mouse ACE, MS/MS fragmentation of substrate-derived product peptides, 3D ion chromatogram of synthetic and endogenous peptides generated by Progenesis QI software, and list of identified ACE-substrate and -nonsubstrate sequences submitted to the WebLogo application in FASTA format (PDF)

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Sparks MA; Crowley SD; Gurley SB; Mirotsou M; Coffman TM Comprehensive Physiology 2014, 4 (3), 1201–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Borghi C; Rossi F High Blood Pressure Cardiovasc. Prev. 2015, 22 (4), 429–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Igic R; Skrbic R Srp. Arh. Celok. Lek. 2014, 142 (11–12), 756–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Jarari N; Rao N; Peela JR; Ellafi KA; Shakila S; Said AR; Nelapalli NK; Min Y; Tun KD; Jamallulail SI; Rawal AK; Ramanujam R; Yedla RN; Kandregula DK; Argi A; Peela LT Clin. Hypertens. 2016, 22 (1), 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Harmer D; Gilbert M; Borman R; Clark KL FEBS Lett. 2002, 532 (1–2), 107–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Herichova I; Szantoova K Endocrine regulations 2013, 47 (1), 39–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Burnham S; Smith JA; Lee AJ; Isaac RE; Shirras AD BMC Genomics 2005, 6, 172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Araujo MC; Melo RL; Cesari MH; Juliano MA; Juliano L; Carmona AK Biochemistry 2000, 39 (29), 8519–8525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Bernstein KE; Shen XZ; Gonzalez-Villalobos RA; Billet S; Okwan-Duodu D; Ong FS; Fuchs S Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2011, 11 (2), 105–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Esther CR Jr.; Howard TE; Marino EM; Goddard JM; Capecchi MR; Bernstein KE Lab. Invest. 1996, 74 (5), 953–965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Fuchs S; Frenzel K; Hubert C; Lyng R; Muller L; Michaud A; Xiao HD; Adams JW; Capecchi MR; Corvol P; Shur BD; Bernstein KE Nat. Med. 2005, 11 (11), 1140–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Kondoh G Nat. Med. 2005, 11 (11), 1142–1143. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Okwan-Duodu D; Datta V; Shen XZ; Goodridge HS; Bernstein EA; Fuchs S; Liu GY; Bernstein KE J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285 (50), 39051–39060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Shen XZ; Li P; Weiss D; Fuchs S; Xiao HD; Adams JA; Williams IR; Capecchi MR; Taylor WR; Bernstein KE Am. J. Pathol. 2007, 170 (6), 2122–2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Bernstein KE; Koronyo Y; Salumbides BC; Sheyn J; Pelissier L; Lopes DH; Shah KH; Bernstein EA; Fuchs DT; Yu JJ; Pham M; Black KL; Shen XZ; Fuchs S; Koronyo-Hamaoui MJ Clin. Invest. 2014, 124 (3), 1000–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Shen XZ; Billet S; Lin C; Okwan-Duodu D; Chen X; Lukacher AE; Bernstein KE Nat. Immunol. 2011, 12 (11), 1078–1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Zhao T; Bernstein KE; Fang J; Shen XZ Lab. Invest. 2017, 97, 764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Chen X; Lu H; Zhao M; Tashiro K; Cassis LA; Daugherty A Arterioscler., Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2013, 33 (9), 2075–2080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Hayek T; Pavlotzky E; Hamoud S; Coleman R; Keidar S; Aviram M; Kaplan M Arterioscler., Thromb., Vasc. Biol. 2003, 23 (11), 2090–2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Chen J; Zhao S; Liu Y; Cen Y; Nicolas C ANZ. journal of surgery 2016, 86 (12), 1046–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Efe C; Cengiz M; Kahramanoglu-Aksoy E; Ylmaz B; Özseker B; Beyazt Y; Tanoglu A; Purnak T; Kav T; Turhan T; et al. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 27 (6), 649–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).de Picoli Souza K; da Silva ED; Batista EC; Reis FC; Silva SM; Castro CH; Luz J; Pesquero JL; Dos Santos EL; Pesquero JB Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6, 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Heimann AS; Favarato MH; Gozzo FC; Rioli V; Carreno FR; Eberlin MN; Ferro ES; Krege JH; Krieger JE Physiol. Genomics 2005, 20 (2), 173–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Khan Z; Shen XZ; Bernstein EA; Giani JF; Eriguchi M; Zhao TV; Gonzalez-Villalobos RA; Fuchs S; Liu GY; Bernstein KE Blood 2017, 130 (3), 328–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Oliverio MI; Madsen K; Best CF; Ito M; Maeda N; Smithies O; Coffman TM American journal of physiology 1998, 274, F43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Perry GJ; Wei CC; Hankes GH; Dillon SR; Rynders P; Mukherjee R; Spinale FG; Dell’Italia LJ J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2002, 39 (8), 1374–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Schuh JR; Blehm DJ; Frierdich GE; McMahon EG; Blaine EH J. Clin. Invest. 1993, 91 (4), 1453–1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Vaughan D Can. J. Cardiol. 2000, 16, 36E–40E. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Yamamoto K; Mano T; Yoshida J; Sakata Y; Nishikawa N; Nishio M; Ohtani T; Hori M; Miwa T; Masuyama TJ Hypertens. 2005, 23 (2), 393–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Bernstein KE; Khan Z; Giani JF; Cao DY; Bernstein EA; Shen XZ Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2018, 14 (5), 325–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Yang HYT; Neff NH J. Neurochem. 1972, 19 (10), 2443–2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Bernstein KE; Ong FS; Blackwell WL; Shah KH; Giani JF; Gonzalez-Villalobos RA; Shen XZ; Fuchs S Pharmacol. Rev. 2013, 65 (1), 1–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Igic R; Behnia R Curr. Pharm. Des. 2003, 9 (9), 697–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Skidgel RA; Erdos EG Peptides 2004, 25 (3), 521–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Sturrock ED; Anthony CS; Danilov SM Peptidyl-Dipeptidase A/Angiotensin I-Converting Enzyme In Handbook of Proteolytic Enzymes; Rawlings ND, Salvesen G, Eds.; Academic Press, 2013; pp 480–494. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Rioli V; Gozzo FC; Heimann AS; Linardi A; Krieger JE; Shida CS; Almeida PC; Hyslop S; Eberlin MN; Ferro ES J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278 (10), 8547–8555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Campbell DJ Bradykinin Peptides In Handbook of Biologically Active Peptides, 2nd ed.; Kastin AJ, Ed.; Academic Press: Boston, 2013; pp 1386–1393. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Fuchs S; Xiao HD; Cole JM; Adams JW; Frenzel K; Michaud A; Zhao H; Keshelava G; Capecchi MR; Corvol P; Bernstein KE J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279 (16), 15946–15953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Fuchs S; Xiao HD; Hubert C; Michaud A; Campbell DJ; Adams JW; Capecchi MR; Corvol P; Bernstein KE Hypertension 2008, 51 (2), 267–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Bernstein KE; Welsh SL; Inman JK Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1990, 167 (1), 310–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Neels HM; van Sande ME; Scharpe SL Clin. Chem. 1983, 29 (7), 1399–1403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Serra CP; Cortes SF; Lombardi JA; Braga de Oliveira A; Braga FC Phytomedicine 2005, 12 (6–7), 424–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Piotto M; Saudek V; Sklenar VJ Biomol NMR 1992, 2 (6), 661–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Vizcaino JA; Deutsch EW; Wang R; Csordas A; Reisinger F; Rios D; Dianes JA; Sun Z; Farrah T; Bandeira N; Binz PA; Xenarios I; Eisenacher M; Mayer G; Gatto L; Campos A; Chalkley RJ; Kraus HJ; Albar JP; Martinez-Bartolome S; Apweiler R; Omenn GS; Martens L; Jones AR; Hermjakob H Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32 (3), 223–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Crooks GE; Hon G; Chandonia JM; Brenner SE Genome Res. 2004, 14 (6), 1188–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Mooney C; Haslam NJ; Pollastri G; Shields DC PLoS One 2012, 7 (10), No. e45012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Corvol P; Williams TA; Soubrier F Methods Enzymol. 1995, 248, 283–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Greening DW; Simpson RJ Methods Mol Biol. (N. Y. NY, U. S.) 2017, 1619, 63–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Arapidi G; Osetrova M; Ivanova O; Butenko I; Saveleva T; Pavlovich P; Anikanov N; Ivanov V; Govorun V Data in brief 2018, 18, 1204–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Kay RG; Challis BG; Casey RT; Roberts GP; Meek CL; Reimann F; Gribble FM Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2018, 32, 1414–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Magalhaes P; Pontillo C; Pej chinovski M; Siwy J; Krochmal M; Makridakis M; Carrick E; Klein J; Mullen W; Jankowski J; Vlahou A; Mischak H; Schanstra JP; Zurbig P; Pape L Proteomics: Clin. Appl 2018, 12, No. e1700163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Parker BL; Burchfield JG; Clayton D; Geddes TA; Payne RJ; Kiens B; Wojtaszewski JFP; Richter EA; James DE Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2017, 16 (12), 2055–2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Vitorino R Proteomics 2018, 18 (2), 1700401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Nanjappa V; Thomas JK; Marimuthu A; Muthusamy B; Radhakrishnan A; Sharma R; Ahmad Khan A; Balakrishnan L; Sahasrabuddhe NA; Kumar S; Jhaveri BN; Sheth KV; Kumar Khatana R; Shaw PG; Srikanth SM; Mathur PP; Shankar S; Nagaraja D; Christopher R; Mathivanan S; Raju R; Sirdeshmukh R; Chatterjee A; Simpson RJ; Harsha HC; Pandey A; Prasad TSK Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42 (D1), D959–D965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Ganu VS; Muller-Eberhard HJ; Hugli TE Mol. Immunol. 1989, 26 (10), 939–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Manning ML; Williams SA; Jelinek CA; Kostova MB; Denmeade SR J. Immunol. 2013, 190 (6), 2567–2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Thurman JM; Kulik L; Orth H; Wong M; Renner B; Sargsyan SA; Mitchell LM; Hourcade DE; Hannan JP; Kovacs JM; Coughlin B; Woodell AS; Pickering MC; Rohrer B; Holers VM J. Clin. Invest. 2013, 123 (5), 2218–2230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Xiang Y; Matsui T; Matsuo K; Shimada K; Tohma S; Nakamura H; Masuko K; Yudoh K; Nishioka K; Kato T Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56 (6), 2018–2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Liang T; Wang N; Li W; Li A; Wang J; Cui J; Liu N; Li Y; Li L; Yang G; Du Z; Li D; He K; Wang G Proteomics 2010, 10 (1), 90–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Profumo A; Mangerini R; Rubagotti A; Romano P; Damonte G; Guglielmini P; Facchiano A; Ferri F; Ricci F; Rocco M; Boccardo FJ Proteomics 2013, 85, 44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Silva EG; Lopez PR; Atkinson EN; Fente CA Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2010, 134 (6), 903–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Capiaumont J; Jacob C; Sarem M; Nabet P; Belleville F; Dousset B Clin. Chim. Acta 2000, 293 (1–2), 89–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Dousset B; Straczek J; Maachi F; Nguyen DL; Jacob C; Capiaumont J; Nabet P; Belleville F Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998, 247 (3), 587–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Maachi F; Straczek J; Jacob C; Belleville F; Nabet P Life Sci. 1995, 56 (25), 2273–2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Koomen JM; Li D; Xiao LC; Liu TC; Coombes KR; Abbruzzese J; Kobayashi RJ Proteome Res. 2005, 4 (3), 972–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Koscielska-Kasprzak K; Bartoszek D; Myszka M; Zabinska M; Klinger M Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 2014, 62 (1), 47–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Laskowski J; Renner B; Le Quintrec M; Panzer S; Hannan JP; Ljubanovic D; Ruseva MM; Borza DB; Antonioli AH; Pickering MC; Holers VM; Thurman JM Kidney Int. 2016, 90 (1), 109–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).McCullough JW; Renner B; Thurman JM Semin. Nephrol. 2013, 33 (6), 543–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Noris M; Remuzzi G Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2015, 66 (2), 359–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Riedl M; Thorner P; Licht C Pediatr. Nephrol. (Berlin) 2017, 32 (1), 43–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Salvadori M; Rosso G; Bertoni E World journal of nephrology 2015, 4 (2), 169–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Thurman JM; Holers VM J. Immunol. 2006, 176 (3), 1305–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Augusto JF; Langs V; Demiselle J; Lavigne C; Brilland B; Duveau A; Poli C; Chevailler A; Croue A; Tollis F; Sayegh J; Subra JF PLoS One 2016, 11 (7), No. e0158871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Liu J; Xie J; Zhang X; Tong J; Hao X; Ren H; Wang W; Chen N Sci. Rep. 2017, 7 (1), 4095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Thurman JM Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2015, 65 (1), 156–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Yang X; Wei RB; Wang Y; Su TY; Li QP; Yang T; Huang MJ; Li KY; Chen XM Med. Sci. Monit 2017, 23, 673–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Jacob C; Hubert J; Maachi F; Punga-Maole A; Dousset B; Junke E; Belleville F Renal Failure 1995, 17 (4), 339–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Jacob C; Maachi F; el Farricha O; Dousset B; Kessler M; Belleville F; Nabet P Clin. Nephrol. 1993, 39 (6), 327–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.