Abstract

The occipital artery (OA) is a critical artery in vascular lesions. However, a comprehensive review of the importance of the OA is currently lacking. In this study, we used the PubMed database to perform a review of the literature on the OA to increase our understanding of its role in vascular lesions. We also provided our typical cases to illustrate the importance of the OA. The OA has several variations. For example, it may arise from the internal carotid artery or anastomose with the vertebral artery. Therefore, the OA may provide a crucial collateral vascular supply source and should be preserved in these cases. The OA is a good donor artery. Consequently, it is used in extra- to intracranial bypasses for moyamoya disease (MMD) or aneurysms. The OA can be involved in dural arteriovenous fistula (DAVF) and is a feasible artery for the embolisation of DAVF. True aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms can occur in the OA; surgical resection and embolisation are the effective treatment approaches. Direct high-flow AVF can occur in the OA; embolisation treatment is a good option in such cases. The OA can also be involved in MMD and brain arteriovenous malformation (AVM) by forming transdural collaterals. For a patient in the prone position, if occipital and suboccipital craniotomies are performed, the OA can also be used for intraoperative angiography. In brief, the OA is a very important artery in vascular lesions.

Keywords: Occipital artery, vascular lesion, clinical importance, review

Introduction

The occipital artery (OA) most commonly originates from the external carotid artery (ECA) and can have some important anatomical variations. For example, it can arise from the internal carotid artery (ICA) or anastomose with the vertebral artery (VA).1 Because of the proximity of the OA to the target recipient vessels, it is used in extra- to intracranial bypasses to both the anterior and the posterior circulation for ischaemic disease or, in the case of giant or fusiform aneurysms, to provide alternative flow when sacrifice of the parent vessel is anticipated.2,3

In addition, the OA is involved in other vascular lesions, such as dural arteriovenous fistula (DAVF), direct high-flow AVF, aneurysm, moyamoya disease (MMD) and brain arteriovenous malformation (AVM), and as a crucial collateral vascular supply source and the path of intraoperative angiography. Hence, the OA is a very important vessel in vascular lesions. However, a comprehensive systematic review of the importance of the OA is currently lacking. Therefore, we performed a review to increase the understanding of the role played by the OA.

Anatomy

The initial segment of the OA is straight as it travels up through the upper neck, and the vessel becomes more tortuous and provides a more redundant blood supply as it travels up the posterior scalp.4 The OA gives off several musculocutaneous branches for the neck and posterior region of the head and several meningeal branches, and its terminal portion is accompanied by the greater occipital nerve.5

The OA is divided into three segments based on the vertical muscle layers through which they run: subcutaneous, transitional and intramuscular.6 The mean length of the OA from its exit from the digastric groove to the level of the superior nuchal line is 81.9 mm; the mean diameters of the vessel are 2.05 mm at its exit from the digastric groove and approximately 2.01 mm at the level of the superior nuchal line.2,7 For an image of the anatomical angiography of the OA, see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Anatomical CTA and DSA imaging of the normal OA. (a) CTA images showing the OA course (arrows). (b) DSA of the ECA showing the OA course (arrows). CTA: computed tomography angiography; DSA: digital subtraction angiography; ECA: external carotid artery; OA: occipital artery.

Variation and importance

OA shares a common origin with another artery

Occasionally, the OA, arising from the ECA, has a common origin with other arteries: the posterior auricular artery, the ascending pharyngeal artery (APA) and the superior thyroid artery often seem to share their origins with the OA.8 When the OA shares a common origin with another artery, the beginning of the common trunk is often in an anomalous location. For instance, the common trunk of the OA and APA often arises proximal to the ICA.9

OA arising from the ICA

An OA that arises from the ICA is extremely rare.10 When the OA arises from the ICA, care is needed to preserve this branch during dissection if a carotid endarterectomy is being performed.11 The OA may serve as an important collateral pathway from the VA to the ICA when the ICA is occluded at its origin.12 In addition, if transarterial embolisation is attempted in an OA arising from the ICA, careful attention is required to prevent embolic cerebral infarctions.13

OA-VA anastomosis

Embryologically, the OA is a remnant of the type I and type II persistent proatlantal intersegmental arteries (PPIAs).5 Therefore, these remnants may connect the OA to the VA via C1 and C2 radicular branches (Figure 2). The OA-VA anastomosis becomes angiographically visible in some pathological cases, especially arterial occlusive diseases (Figure 3).14 When the OA is injured, the posterior circulation may suffer vertebrobasilar insufficiency or ischaemic diseases.15

Figure 2.

Anastomosis between OA with VA in a normal case. (a) and (b) CTA showing the connection between the OA and the VA via radicular branches (arrows). (c) and (d) DSA of the VA and the ECA showing the connection between the OA and the VA via radicular branches (arrows). VA: vertebral artery.

Figure 3.

Anastomosis between OA with VA in an ICA occlusive case. (a) and (b) Anteroposterior and lateral DSA of the VA showing the connection between the OA and the VA via radicular branches (arrows). ICA: internal carotid artery.

The PPIAs can be classified into types I and II.16,17 When a large anastomotic artery arises from the posterior wall of ECA, the type II PPIA (occipital subtype) may potentially be similar in appearance to the OA. It courses upward and becomes the distal part of the VA supplying the basilar system. It also gives rise to a musculocutaneous branch to replace the OA supplying the structures of the posterior portion of the vault.18

Bypass surgery

Introduction

The OA is very useful as a graft vessel because its course is winding and flexible, allowing redundancy.5 When the OA is used as a donor graft for revascularisation, several types of bypasses can be performed, such as OA-posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA), OA-anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA), OA-VA, OA-posterior cerebral artery (PCA) and OA-middle cerebral artery (MCA) bypasses.2,19–21

OA-PICA bypass

Complex aneurysms of the PICA and VA sometimes require PICA revascularisation.22 Even if there is a tumour at the craniovertebral junction, an OA-PICA bypass may be performed prior to the tumour resection to prevent ischaemic complications.23 A 2017 study by Matsushima et al. showed that an OA bypass to the p2–5 segments of the PICA was feasible.24 In practice, however, p2 and p3 are the most frequently used segments.25

Several factors contribute to the success of the OA-PICA bypass procedure. First, an adequate dissection of the OA is necessary. Second, a wide operative field is required for a safe procedure. Third, accurate dural closure without disturbing the bypass flow is mandatory.26 In addition, aspirin should be administered the night before OA-PICA bypass and for at least one year after the procedure.27 A case with PICA aneurysm treated by clipping assisted with OA-PICA bypass is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

OA-PICA bypass in a case with a PICA aneurysm. (a) 3D DSA of VA showing an aneurysm on the origin of PICA (arrow). (b) DSA of the ECA showing the course of OA (arrow). (c) Postoperative CTA showing aneurysm clipping (black arrow) and OA-PICA bypass (white arrow). (d) Postoperative CTA showing the OA’s path into the posterior fossa (white arrow). PICA: posterior inferior cerebellar artery.

Bypasses from the OA to other arteries

OA-AICA anastomosis

Because the AICA is too thin, causing it to be mismatched with the OA, OA-AICA anastomosis is rarely performed.28 Despite the difficulty, an OA-AICA bypass can be performed. For instance, in 2012, Fujimura et al. treated a ruptured intrameatal AICA aneurysm, and OA-AICA anastomosis with aneurysm trapping was performed.29 It is important to dissect a sufficiently long piece of the OA to be able to reach the AICA at the petrous surface, as the dissection may need to extend to the level of the mastoid process.30

OA-PCA anastomosis

OA-PCA bypass is rarely performed but can be used as an alternative to conventional superficial temporal artery (STA)-PCA bypass.31 Because of the long distance between the OA and PCA, there is sometimes a need for interposition grafts, such as the saphenous vein and the radial artery.32 OA-PCA bypass can be used in the treatment of PCA aneurysms and MMD.33,34

In the treatment of aneurysms, OA-PCA bypass techniques are associated with a high rate of complications, such as visual deficits.33 Because OA-PCA bypass for MMD is performed on the surface of the occipital lobe, it has less risk when performed for MMD than when applied to aneurysms.35

OA-MCA anastomosis

STA-MCA bypass is often used in a variety of MCA diseases.36,37 However, when the STA is absent or is too hypoplastic to be used as a donor for revascularisation, OA-MCA bypass may be an effective treatment option.37 For instance, in 2017, Kimura et al. treated four cases of symptomatic cerebral ischaemia in which the STA was absent or unavailable. These cases were treated by revascularisation from the OA to the angular artery of the MCA.20

OA-VA anastomosis

The mean diameter of the V3 segment is usually significantly larger than the diameter of the OA at this level. Therefore, if the clinical scenario calls for a high-flow bypass, the diameter of the OA may not provide adequate flow.2,7 However, when the blood flow of the OA-VA bypass is sufficient, such as symptomatic bilateral severe VA stenosis at the origin, OA-VA anastomosis can sometimes be performed more safely and more easily than bypass grafting and endovascular treatment.38

OA as an interposition graft

Short arterial interposition graft anastomosis is often used in cerebral revascularisation.39 OA interposition grafting is a useful option.40 However, graft bypass has several limitations, such as the need for complex procedures, in that it requires harvesting the graft and performing an additional anastomosis between the initial donor and the graft vessel, the production of multiple surgical scars and an increased risk of occlusion of the bypass.41

Fate of OA-cerebral artery bypasses

OA-cerebral artery bypasses have especially high long-term patency rates, but some bypasses may become occluded or develop stenosis in the long term.42 In addition, Sundt et al. reported that OA has a 13% rate of spasm and occlusion. Therefore, attempts should be made to handle the vessel adventitia rather than the vessel wall itself, as this course of action will decrease the risk of spasm and intraluminal thrombosis from damage during the vessel harvest.43

DAVF

Introduction

DAVFs most commonly involve the transverse-sigmoid sinuses and usually have two main feeding arteries: the middle meningeal artery (MMA) and the OA.44,45 The OA provides significant blood supply to portions of the posterior fossa dura through transosseous and transforaminal branches. These collateral branches also provide vascularity to the walls of the venous sinuses in the posterior fossa, which explains the involvement of the OA and its branches in DAVFs of this region.4,46

Meningeal branch and anastomosis

The stylomastoid artery arises from the first ascending segment and anastomoses with the petrosquamous branch of the MMA.47 Distal to the origin of the mastoid branch, lateral meningeal branches may enter the skull via the small parietal foramen, and there are usually anastomoses with MMA branches.48 These meningeal branches are in haemodynamic balance with those arising from the neuromeningeal trunk of the APA, with the petrosquamous branch of the MMA and with the meningeal branches of the VA.48–51

Treatment and prognosis

Transverse-sigmoid sinuses DAVFs that are supplied by robust MMAs can be successfully treated via a transarterial approach.52 However, when there is no MMA, the OA has to provide the only transarterial approach.46 In the past, the OA was a poor option because the arterial feeders from the OA are transosseous, resulting in poor penetration of the liquid embolic material.53 However, the use of a double-lumen balloon catheter may help to overcome this limitation by increasing the proximal resistance and enhancing distal penetration of the liquid embolic material.54

Currently, the new insights opened by the use of double-lumen balloons may change the strategy for the treatment of transverse-sigmoid sinuses DAVFs. With the aid of the new double-lumen balloon, the OA may now represent a valuable alternative to the MMA for the embolisation of transverse-sigmoid sinuses DAVFs with the liquid embolic material Onyx (Medtronic-Covidien, Irvine, CA).45,55

During the OA approach, the embolisation from the proximal OA should be carefully avoided, as it can be dangerous because of the potential presence of either seen or unseen occipito-vertebral anastomoses that can open. Thus, the distal catheter position is vital to prevent the possibility of basilar stroke.49,56 In addition, the stylomastoid branch of the OA supplying the descending portion of CN VII must also be preserved to avoid CN VII palsy.45 Because the OA supplies blood to several muscles and the scalp, ischaemia can occur during embolisation.57

The endovascular treatment of a case with DAVF supplied by OA is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Embolisation via the OA with Onyx in a DAVF case. (a) and (b) DSA of the ECA and the VA showing a DAVF supplied by the OA and the posterior meningeal artery (arrows). (c) DSA showing embolisation of the DAVF via the OA (arrow). (d) DSA of the VA showing that the DAVF was embolised completely. DAVF: dural arteriovenous fistula.

Aneurysm

OA aneurysms include pseudoaneurysm and true aneurysm.58 Pseudoaneurysm is often caused by blunt traumatic compression of the OA and is the result of OA wall rupture, with all layers of the artery focally absent.59 True aneurysm is defined by the presence of a defect in the internal elastic lamina that leads to dilatation of the intima, media and adventitia, creating a lumen. This type of lesion can occur secondary to infection and autoimmune disease, or it can arise from congenital defects of the elastic membrane.60

OA aneurysms can present as enlarging, tender, pulsatile or painful masses, among other manifestations, and the most common symptom, occurring in more than 50% of cases, is pain in the occipital region.61 Currently, the gold standard for diagnosing OA aneurysms continues to be digital subtraction angiography (DSA). Other non-invasive imaging by computed tomography angiography (CTA), ultrasound (US) or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) can be used as a screening tool.59,62

OA aneurysms have been approached by surgical excision, endovascular methods, percutaneous US-guided thrombosis, direct manual compression and observation, among which surgical resection is the most commonly reported treatment.63 In addition, when OA aneurysms are located in the first and second segments, transcatheter arterial embolisation provides a more effective means of treatment.63

Direct high-flow AVF

A direct high-flow AVF fed by the OA is a vascular lesion for which the adjacent internal jugular vein or transverse-sigmoid sinuses often act as drainage veins.64 The OA can rupture as a result of traumatic pseudoaneurysm, congenital factors or vascular dysplastic conditions such as neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1).65

The pathogenesis of spontaneous OA AVF remains unclear but may rest on congenital factors. The first hypothesis is persistence of the primitive arteriovenous communication and capillary agenesis. As a second hypothesis, AVFs may originate from vascular hamartomas. The third hypothesis is formation of a fistula at the site of arteriovenous crossing.66

Direct high-flow AVFs should receive treatment, including ligation of the feeding arteries, surgical removal, embolisation or a combination of these approaches, in which transarterial and transvenous approaches can be chosen and used.67 The arterial supply pattern of an AVF is very important in therapeutic decision making. If the AVF has only one feeding artery, surgical origin ligation for the AVF can be considered.67

However, in some direct high-flow AVFs, the OA may play a smaller contributor role. For instance, Takegami et al. reported a spontaneous high-flow AVF associated with NF1, in which the VA was the main contributor, the OA and the thyrocervical artery and the contralateral VA were smaller contributors, and the AVF drained into the internal vertebral plexus.68 In this situation, the fistula embolisation via VA was necessary and feasible.

Transdural collaterals

Transdural collaterals are defined as blood supply to the cortex from branches of the ECA. Transdural collaterals have been most commonly reported in MMD. In addition, in AVM, transdural collateral circulation can occur.69,70 In MMD, the cerebral ischaemia functions as a biological driver of collateral development.70 AVM-induced high wall shear stress can cause angiogenesis and arteriogenesis, resulting in transdural collateral development.69 Among the transdural collaterals, MMA is the most commonly involved artery, but the OA can also be involved in MMD and AVM (Figures 6 and 7).

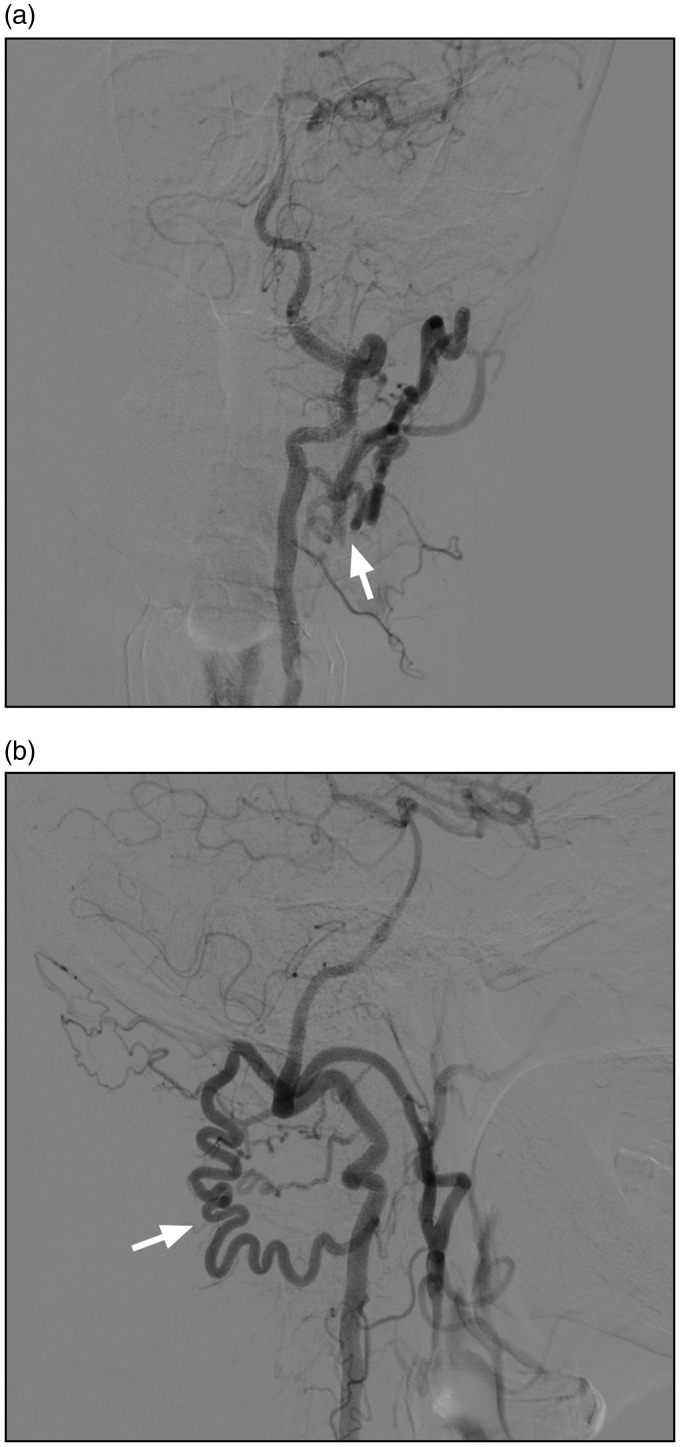

Figure 6.

Transdural collaterals between the OA and PCA in an MMD case. (a) and (b) Different arterial phases of DSA of OA showing the transdural anastomosis between the OA and PCA (arrow and ellipse). The PCA received its blood supply from the OA. (a) The early arterial phase. (b) The late arterial phase. DSA: digital subtraction angiography; MMD: moyamoya disease; PCA: posterior cerebral artery.

Figure 7.

Transdural collaterals between the OA and AVM in an AVM case. (a) and (b) Lateral DSA of the ICA and VA showing the AVM located at the parietal and occipital lobes. (c) DSA of the ECA showing the transdural collaterals between the OA and the AVM (ellipse). AVM: arteriovenous malformation.

Path of intraoperative DSA

Intraoperative angiography has been widely used during neurovascular procedures.71 Femoral, radial and retrograde catheterisations of the STA have all been reported for intraoperative DSA.71,72 For a patient in the prone position, if occipital and suboccipital craniotomies are performed, the OA can also be used for intraoperative DSA. For instance, in 2008, Horiuchi et al. reported two patients with DAVFs of transverse-sigmoid sinuses. Intraoperative DSA in the prone position was performed, with good efficacy and safety.73

Summary

The OA originates from the ECA and can have some important variations. The OA may be a crucial collateral vascular supply source. Because of the proximity of the OA to the target recipient vessels, it is used in extra- to intracranial bypasses for ischaemic disease and complex aneurysms. Currently, various types of revascularisation are performed, including bypasses between the OA and the PICA, AICA, VA, PCA, MCA and other vessels.

The OA can act as a feeding artery for DAVFs and is a feasible artery for the embolisation, but careful attention must be paid to dangerous potential anastomoses to prevent basilar stroke. The OA can develop aneurysms; these aneurysms should be treated. Surgical resection is the most common treatment, and embolisation is an effective alternative. Direct high-flow AVF can occur in the OA, in which case embolisation treatment is a good option. The OA can be involved in the MMD and AVM to form transdural collaterals. In addition, the OA can also be used for intraoperative DSA.

In brief, the OA is a very important artery in vascular lesions.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Oner Z, Oner S, Kahraman AS. The right vertebral artery originating from the right occipital artery and the absence of the transverse foramen: a rare anatomical variation. Surg Radiol Anat 2017; 39: 1397–1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ates O, Ahmed AS, Niemann D, et al. The occipital artery for posterior circulation bypass: microsurgical anatomy. Neurosurg Focus 2008; 24: E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roski RA, Spetzler RF, Hopkins LN. Occipital artery to posterior inferior cerebellar artery bypass for vertebrobasilar ischemia. Neurosurgery 1982; 10: 44–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alvernia JE, Fraser K, Lanzino G. The occipital artery: a microanatomical study. Neurosurgery 2006; 58: ONS114–22. discussion ONS114-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lasjaunias P, Theron J, Moret J. The occipital artery. Anatomy – normal arteriographic aspects – embryological significance. Neuroradiology 1978; 15: 31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukuda H, Evins AI, Burrell JC, et al. A safe and effective technique for harvesting the occipital artery for posterior fossa bypass surgery: a cadaveric study. World Neurosurg 2014; 82: e459–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawashima M, Rhoton AL, Jr, Tanriover N, et al. Microsurgical anatomy of cerebral revascularization. Part II: posterior circulation. J Neurosurg 2005; 102: 132–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aggarwal NR, Krishnamoorthy T, Devasia B, et al. Variant origin of superior thyroid artery, occipital artery and ascending pharyngeal artery from a common trunk from the cervical segment of internal carotid artery. Surg Radiol Anat 2006; 28: 650–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen JE, Leker RR, Moshe Gomori J, et al. Pharyngo-occipital artery variant arising proximal to occluded internal carotid artery: the risk of an unnecessary endarterectomy. J Clin Neurosci 2014; 21: 529–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uchino A, Saito N, Okano N, et al. Aberrant internal carotid artery associated with occipital artery arising from the internal carotid artery. Surg Radiol Anat 2015; 37: 1137–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sundick SA, Weaver M, Faries PL, et al. Aberrant origin of occipital artery proximal to internal carotid artery stenosis. J Vasc Surg 2014; 59: 244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uchino A, Saito N, Mizukoshi W, et al. Anomalous origin of the occipital artery diagnosed by magnetic resonance angiography. Neuroradiology 2011; 53: 853–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang G, Gao X, Li Z, et al. Endovascular treatment for dural arteriovenous fistula at the foramen magnum: report of five consecutive patients and experience with balloon-augmented transarterial Onyx injection. J Neuroradiol 2013; 40: 134–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holodny AI. Supply of the unilateral circulation of the brain by an occipital artery anastomosis – a case report. Angiology 2005; 56: 93–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bacci D, Valecchi D, Sgambati E, et al. Compensatory collateral circles in vertebral and carotid artery occlusion. Ital J Anat Embryol 2008; 113: 265–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vasovic L, Mojsilovic M, Andelkovic Z, et al. Proatlantal intersegmental artery: a review of normal and pathological features. Childs Nerv Syst 2009; 25: 411–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexander MD, English J, Hetts SW. Occipital artery anastomosis to vertebral artery causing pulsatile tinnitus. J Neurointerv Surg 2014; 6: e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen JE, Grigoriadis S, Itshayek E. Type II proatlantal artery (occipital subtype) with bilateral absence of the vertebral arteries. Clin Anat 2011; 24: 950–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanakita S, Lenck S, Labidi M, et al. The occipital artery as an alternative donor for low-flow bypass to anterior circulation after internal carotid artery occlusion failure prior to exenteration for an atypical cavernous sinus meningioma. World Neurosurg 2018; 109: 10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimura T, Morita A. Occipital artery to middle cerebral artery bypass: operative nuances. World Neurosurg 2017; 108: 201–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mao Y. Revascularization with the occipital artery to treat aneurysms in the posterior circulation. World Neurosurg 2014; 82: e415–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi L, Xu K, Sun X, et al. Therapeutic progress in treating vertebral dissecting aneurysms involving the posterior inferior cerebellar artery. Int J Med Sci 2016; 13: 540–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishi Y, Nakayama N, Kobayashi H, et al. Successful removal of a metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor in the craniovertebral junction using an occipital artery to posterior inferior cerebellar artery bypass. Case Rep Neurol 2014; 6: 139–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsushima K, Matsuo S, Komune N, et al. Variations of occipital artery-posterior inferior cerebellar artery bypass: anatomic consideration. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown) 2018; 14: 563–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fukuda H, Evins AI, Iwasaki K, et al. The role of alternative anastomosis sites in occipital artery-posterior inferior cerebellar artery bypass in the absence of the caudal loop using the far-lateral approach. J Neurosurg 2017; 126: 634–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park W, Ahn JS, Park JC, et al. Occipital artery-posterior inferior cerebellar artery bypass for the treatment of aneurysms arising from the vertebral artery and its branches. World Neurosurg 2014; 82: 714–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Couldwell WT, Neil JA. Far-lateral approach for surgical treatment of fusiform PICA aneurysm. Neurosurg Focus 2015; 38: Video10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Touho H, Karasawa J, Ohnishi H, et al. Anastomosis of occipital artery to anterior inferior cerebellar artery with interposition of superficial temporal artery. Case report. Surg Neurol 1993; 40: 164–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fujimura M, Inoue T, Shimizu H, et al. Occipital artery-anterior inferior cerebellar artery bypass with microsurgical trapping for exclusively intra-meatal anterior inferior cerebellar artery aneurysm manifesting as subarachnoid hemorrhage. Case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2012; 52: 435–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ausman JI, Diaz FG, Vacca DF, et al. Superficial temporal and occipital artery bypass pedicles to superior, anterior inferior, and posterior inferior cerebellar arteries for vertebrobasilar insufficiency. J Neurosurg 1990; 72: 554–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaku Y, Funatsu N, Tsujimoto M, et al. STA-MCA/STA-PCA bypass using short interposition vein graft. Acta Neurochir Suppl 2014; 119: 79–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Touho H, Karasawa J, Ohnishi H, et al. Anastomosis of occipital artery to posterior cerebral artery with interposition of superficial temporal artery using occipital interhemispheric transtentorial approach: case report. Surg Neurol 1995; 44: 245–249; discussion 9–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang SW, Abla AA, Kakarla UK, et al. Treatment of distal posterior cerebral artery aneurysms: a critical appraisal of the occipital artery-to-posterior cerebral artery bypass. Neurosurgery 2010; 67: 16–25. discussion 25–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kazumata K, Kamiyama H, Saito H, et al. Direct anastomosis using occipital artery for additional revascularization in moyamoya disease after combined superficial temporal artery-middle cerebral artery and indirect bypass. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown) 2017; 13: 213–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayashi T, Shirane R, Tominaga T. Additional surgery for postoperative ischemic symptoms in patients with moyamoya disease: the effectiveness of occipital artery-posterior cerebral artery bypass with an indirect procedure: technical case report. Neurosurgery 2009; 64: E195–196. discussion E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nomura M, Tamase A, Kamide T, et al. Superficial temporal artery-middle cerebral artery bypass using a thick STA after endarterectomy: a rescue technique. J Neurol Surg A Cent Eur Neurosurg 2017; 78: 595–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thines L, Durand A, Penchet G, et al. Microsurgical neurovascular anastomosis: the example of superficial temporal artery to middle cerebral artery bypass. Technical principles. Neurochirurgie 2014; 60: 158–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katsuki M, Yamamoto Y, Wada N, et al. Occipital artery to extracranial vertebral artery anastomosis for bilateral vertebral artery stenosis at the origin: a case report. Surg Neurol Int 2018; 9: 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kubota H, Tanikawa R, Katsuno M, et al. Reconstruction of intracranial vertebral artery with radial artery and occipital artery grafts for fusiform intracranial vertebral aneurysm not amenable to endovascular treatment: technical note. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2013; 155: 1517–1524. discussion 1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chung Y, Lee SH, Ryu J, et al. Tailored double-barrel bypass surgery using an occipital artery graft for unstable intracranial vascular occlusive disease. World Neurosurg 2017; 101: 813 e5–e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feng X, Meybodi AT, Rincon-Torroella J, et al. Surgical technique for high-flow internal maxillary artery to middle cerebral artery bypass using a superficial temporal artery interposition graft. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown) 2017; 13: 246–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramanathan D, Temkin N, Kim LJ, et al. Cerebral bypasses for complex aneurysms and tumors: long-term results and graft management strategies. Neurosurgery 2012; 70: 1442–1457. discussion 57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nossek E, Chalif DJ, Dehdashti AR. How I do it: occipital artery to posterior inferior cerebellar artery bypass. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2014; 156: 971–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guo Y, Yu J, Zhao Y, et al. Progress in research on intracranial multiple dural arteriovenous fistulas. Biomed Rep 2018; 8: 17–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu K, Yang X, Li C, et al. Current status of endovascular treatment for dural arteriovenous fistula of the transverse-sigmoid sinus: a literature review. Int J Med Sci 2018; 15: 1600–1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stiefel MF, Albuquerque FC, Park MS, et al. Endovascular treatment of intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulae using Onyx: a case series. Neurosurgery 2009; 65: 132–139. discussion 9–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Upile T, Jerjes W, Nouraei SA, et al. The stylomastoid artery as an anatomical landmark to the facial nerve during parotid surgery: a clinico-anatomic study. World J Surg Oncol 2009; 7: 71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abud TG, Houdart E, Saint-Maurice JP, et al. Safety of Onyx transarterial embolization of skull base dural arteriovenous fistulas from meningeal branches of the external carotids also fed by meningeal branches of internal carotid or vertebral arteries. Clin Neuroradiol 2018; 28: 579–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Geibprasert S, Pongpech S, Armstrong D, et al. Dangerous extracranial-intracranial anastomoses and supply to the cranial nerves: vessels the neurointerventionalist needs to know. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2009; 30: 1459–1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sloniewski P, Dzierzanowski J, Och W. Aneurysm of the meningeal branch of the occipital artery connecting with the distal portion of the posteroinferior cerebellar artery by the dural fistula. Folia Morphol (Warsz) 2008; 67: 292–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kiyosue H, Tanoue S, Okahara M, et al. Angioarchitecture of transverse-sigmoid sinus dural arteriovenous fistulas: evaluation of shunted pouches by multiplanar reformatted images of rotational angiography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2013; 34: 1612–1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Griessenauer CJ, He L, Salem M, et al. Middle meningeal artery: gateway for effective transarterial Onyx embolization of dural arteriovenous fistulas. Clin Anat 2016; 29: 718–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cognard C, Januel AC, Silva NA, Jr, et al. Endovascular treatment of intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulas with cortical venous drainage: new management using Onyx. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008; 29: 235–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gabrieli J, Clarencon F, Di Maria F, et al. Occipital artery: a not so poor artery for the embolization of lateral sinus dural arteriovenous fistulas with Onyx. J Neurointerv Surg 2017; 9: e8–e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clarencon F, Di Maria F, Gabrieli J, et al. Double-lumen balloon for Onyx® embolization via extracranial arteries in transverse sigmoid dural arteriovenous fistulas: initial experience. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2016; 158: 1917–1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chiu AHY, Aw GE, David Wenderoth J. Reply to: Occipital artery: a not so poor artery for the embolization of lateral sinus dural arteriovenous fistulas with Onyx. J Neurointerv Surg 2017; 9: e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Singla A, Fargen KM, Hoh B. Onyx extrusion through the scalp after embolization of dural arteriovenous fistula. J Neurointerv Surg 2016; 8: e38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chaudhry NS, Gaynor BG, Hussain S, et al. Etiology and treatment modalities of occipital artery aneurysms. World Neurosurg 2017; 102: 697.e1–e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim HS, Son BC, Lee SW, et al. A rare case of spontaneous true aneurysm of the occipital artery. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2010; 47: 310–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Merei FT, Gallyas F, Horvath Z. Elastic elements in the media and adventitia of human intracranial extracerebral arteries. Stroke 1980; 11: 329–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Srinivasan VM, Karas PJ, Sen AN, et al. Occipital artery pseudoaneurysm after posterior fossa craniotomy. World Neurosurg 2017; 98: 868.e1–e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nagpal N, Bhargava GS, Singh B. Occipital artery pseudoaneurysm: a rare scalp swelling. Indian J Surg 2013; 75: 275–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mendez JC, Sendra J, Poveda P, et al. Endovascular treatment of traumatic aneurysm of the occipital artery. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2006; 29: 486–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Imahori T, Fujita A, Hosoda K, et al. Endovascular internal trapping of ruptured occipital artery pseudoaneurysm associated with occipital-internal jugular vein fistula in neurofibromatosis type 1. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2016; 25: 1284–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tanaka T, Hasegawa Y, Kanki T, et al. [Combination of intravascular surgery and surgical operation for occipital subcutaneous arteriovenous fistula in a patient with neurofibromatosis type I]. No Shinkei Geka 2002; 30: 309–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bret J, Kunc Z. Fistula between three main cerebral arteries and a large occipital vein. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1969; 32: 308–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Senoglu M, Yasim A, Gokce M, et al. Nontraumatic scalp arteriovenous fistula in an adult: technical report on an illustrative case. Surg Neurol 2008; 70: 194–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Takegami T, Imai K, Umezawa K, et al. [Endovascular trapping using a tandem balloon technique for a spontaneous vertebrovertebral fistula associated with neurofibromatosis type 1]. No Shinkei Geka 2012; 40: 705–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bervini D, Morgan MK, Stoodley MA, et al. Transdural arterial recruitment to brain arteriovenous malformation: clinical and management implications in a prospective cohort series. J Neurosurg 2017; 127: 51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yu J, Guo Y, Xu B, et al. Clinical importance of the middle meningeal artery: a review of the literature. Int J Med Sci 2016; 13: 790–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nossek E, Chalif DJ, Buciuc R, et al. Intraoperative angiography for arteriovenous malformation resection in the prone and lateral positions, using upper extremity arterial access. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown) 2017; 13: 352–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sheikh BY. Minimal invasive method for intraoperative angiography using the superficial temporal artery with preservation of its trunk. Surg Neurol 2008; 70: 640–643. discussion 643–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Horiuchi T, Nitta J, Uehara T, et al. Intraoperative angiography through the occipital artery and muscular branch of the vertebral artery: technical note. Surg Neurol 2008; 70: 645–648. discussion 648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]