Short abstract

Background

Bile acid levels and liver function tests may be normal at presentation in women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. The biochemical results of patients presenting with pruritus typical for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy were reviewed.

Methods

A retrospective audit of women coded as having intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy over a three-year period.

Results

One hundred and ninety-three women (1.1% of the obstetric population) presented with pruritus typical of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Forty (21%) of these women had normal biochemistry at presentation, half subsequently developing abnormal results. Women with a history of allergic reactions were more likely to develop intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy.

Conclusions

Normal biochemistry should not preclude a trial of ursodeoxycholic acid in women with distressing pruritus typical for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Biochemical tests which are more sensitive and specific in the diagnosis of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy would be valuable. Investigation of other populations with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy regarding a possible association with atopy/allergy would be interesting.

Keywords: Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, total serum bile acids, liver function tests, ursodeoxycholic acid

Introduction

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is the most common pregnancy-specific liver disorder.1 It is characterised by pruritus without rash, typically affecting the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. Biochemical abnormalities include elevated total serum bile acids (TSBAs), liver function tests (LFT), and serum bilirubin. Biochemical abnormalities, however, may be absent at the time of initial presentation. In addition, TSBA levels may be elevated in a variety of other conditions. ICP may be associated with adverse fetal outcomes, as well as maternal distress due to sleep deprivation and itch. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) relieves pruritus, improves maternal liver function, and improves fetal outcome in ICP. The aim of this study was to determine the proportion of women presenting with typical symptoms of ICP who manifested normal TSBA and LFT, and how many of these women developed biochemical abnormalities on subsequent testing.

Methods

A retrospective audit of women coded as having a diagnosis of ICP in pregnancy in a medical record database over a three-year period at a quaternary obstetric hospital was performed. Results were defined as abnormal if TSBA was greater than 10 µmol, aspartate transaminase greater than 40 U/l, or alanine aminotransferase greater than 40 U/l. Serum bilirubin and gamma glutamyl transferase were not assessed. The women’s medical records were examined for the mode and gestation of presentation, ethnicity, existing medical conditions, and pathology results.

Results

One hundred and ninety-three women presented with symptoms suggestive of ICP over a three-year period from 2014 to 2017, representing an incidence of 1.1% in the general obstetric population. Ninety women were primigravida. Of the multiparous women 44% had been diagnosed with ICP in a previous pregnancy. Mean maternal age was 29 years. There were five twin pregnancies. The mean gestational age at presentation was 34 weeks (range 14–40 weeks). Forty-nine per cent of women were White, 25% Indian/South Asian, 11% South-East Asian, and 3% Indigenous Australian. Fifty-six women (29%) who developed ICP reported significant previous allergic reactions to medications (19%), foods (8%), or topical preparations (10%). This was significantly higher than in the overall group of pregnant women in the corresponding time (14.6%) (p = 0.0002). Pre-existing gastrointestinal conditions included inflammatory bowel disease (four women), hepatitis C (5) and hepatitis B (3), coeliac disease (4), and single cases of Wilson’s disease and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Six women reported chronic skin conditions – three eczema, two psoriasis, and one with urticaria. Pregnancy was complicated by gestational diabetes mellitus in 36 women (19%) and preeclampsia in six women (3%).

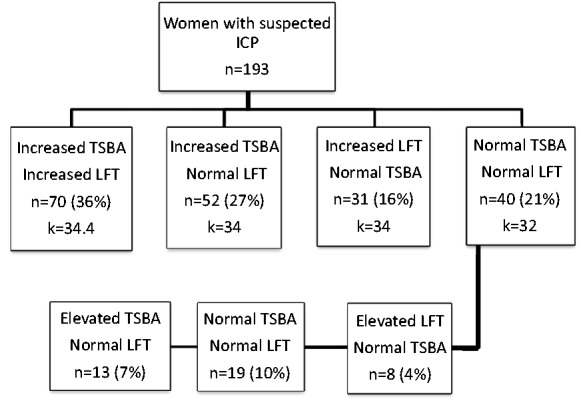

At presentation 70 women (36%) had elevated TSBA and LFT, 52 (27%) elevated TSBA alone, 31 (16%) elevated LFT alone, and 40 (21%) no biochemical abnormality (Figure 1). Of the 40 women with characteristic symptoms but normal biochemistry on presentation, 21 (52%) subsequently developed elevated TSBA or LFT between nine and 90 days after initial presentation with pruritus. In 11 of these 21 women, abnormal biochemistry developed despite treatment with UDCA. UDCA was offered to all symptomatic women with the exception of those near term gestation. Overall 54% of women elected to receive treatment with UDCA. Pruritus improved in 68% of women treated with UDCA. The initial dose of UDCA was 750 mg/day, titrated to a maximum of 2000 mg/day depending on symptomatic response. No women received treatment with glucocorticoids, S-adenosyl-l-methionine, cholestyramine, or guar gum. UDCA therapy resulted in an improvement in pruritus in 62.5% of the women with normal biochemistry at presentation. Of this small group, six of eight women (75%) who subsequently developed abnormal biochemistry reported improvement in pruritus, compared with four of the eight women (50%) with persistently normal biochemistry (p = 0.3).

Figure 1.

TSBA and LFT in women with typical symptoms of ICP. k = mean gestation at presentation with symptoms for each group (weeks). ICP: intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy; LFT: liver function test; TSBA: total serum bile acid.

Ten of the women presented with bile acid levels greater than 40 µmol/L. There were no stillbirths.

Discussion

The diagnostic criteria used in previous series of ICP have varied in biochemical and clinical criteria, upper limits of normal for TSBA levels ranging between 6 and 20 µmol/l.2 The most commonly accepted normal upper limit is 10 µmol/l, though this is dependent on the population studied and the analytical method used. A group of asymptomatic pregnant women with high levels of total TSBA and normal LFT has been classified as asymptomatic hypercholanemia of pregnancy (AHP).3 While Castano et al. reported normal pregnancy outcomes with AHP in Argentinian women, Feng and He reported 141 asymptomatic women with elevated TSBA in Si Chuan, China in which there was a high rate of adverse fetal outcomes, including meconium-stained amniotic fluid in 20%, fetal distress in 6.4%, and stillbirth in 3.5%.4,5

Several investigators have assessed bile acid profiles on electrophoresis seeking better biochemical markers for ICP. The bile acid ratio of cholic acid to chenodeoxycholic acid contributed little to the diagnosis of ICP.3,6 The combination of lithocholic acid levels and UDCA/lithocholic acid ratio provided more accurate values than total serum TSBA alone.3 Autotaxin activity is a highly sensitive marker for ICP and reliably distinguished ICP from other pruritic disorders of pregnancy and preeclampsia/HELLP syndrome.7 Assays for autotaxin activity are not widely available, and levels are elevated in non-pregnant subjects with hepatic fibrosis, NAFLD, chronic hepatitis B or C, and other cholestatic liver disorders.

Kenyon et al. prospectively identified 10 pregnant women with pruritus suggestive for ICP with normal biochemistry, all of whom subsequently developed abnormalities of liver function over a median of 4.5 weeks.8 The audit presented suggests this may be common, with 37% of women with typical symptoms of ICP having normal TSBA, and 21% having normal TSBA and LFTs at the time of presentation. Half of the women with initially normal values subsequently developed abnormal biochemistry. This represented 10% of women presenting with typical symptoms of ICP. Nezer et al. presented a retrospective cohort study of 351 women presenting with undefined pruritus in pregnancy. Thirty-five per cent had elevated TSBA and LFTs, 14% elevated TSBA alone, 16% elevated LFTs with normal TSBA, and 35% had normal TSBA and LFTs.9

Kenyon et al. reported an overall prevalence of pruritus in pregnancy of 23%.10 Itch that was most severe ‘all over’ or localised to palms and soles characterised pruritus in women with ICP. Pruritus in pregnant women unrelated to ICP was most severe on the abdomen. The prevalence of pruritus in non-pregnant patients with chronic liver disease was 40% in one study.11 Pruritus in liver disease most commonly involved the back (63%); abdomen (29%); and face, head, and neck (16%). Pruritus with liver disease affected the hands and feet in only 9 and 13% of patients, respectively.

TSBA may be elevated in a wide variety of hepatic disorders including NAFLD, acute and chronic hepatitis, drug-induced liver injury, cirrhosis, and intra- and extra-hepatic cholestasis.12,13 TSBA may also be elevated in hyperemesis gravidarum. Notably, TSBA may be elevated in non-pregnant individuals with pruritus in whom liver disease has been excluded.14 Eisendle et al. reported that 15 of 18 non-pregnant patients (83%) with pruritus of unknown origin had elevated TSBA levels.14 Pruritus substantially improved in nine patients treated with cholestyramine and UDCA.

A meta-analysis found that UDCA improves pruritus, decreased the level of TSBA and LFTs, resulted in fewer premature births, reduced fetal distress, fewer neonates in the intensive care unit, and increased gestational age and birthweight in women with ICP.15 UDCA was associated with a total resolution of pruritus in 41.6% and improvement in 61.3% of cases of ICP, compared with 8.6 and 25.7% of cases receiving placebo.16 UDCA is well tolerated by pregnant women and no adverse effects have been observed in newborns.

This study has significant weaknesses. As a retrospective audit there were limitations on the acquisition and interpretation of data. It was not possible to confidently ascertain whether TSBA levels were collected in the fasting or non-fasting state. A standardised schedule of biochemistry follow-up for those with initially normal results was not followed.

Conclusions

TSBA levels may not be a sensitive test for ICP at the time of initial presentation. In addition, elevated TSBA is not specific for ICP. Prospective placebo-controlled studies assessing symptomatic benefit of UDCA therapy in women who present with pruritus typical for ICP with normal biochemistry would be useful. Pending such studies normal biochemistry should not preclude a trial of UDCA therapy in women with distressing pruritus in a distribution typical for ICP. Further investigation regarding autotaxin activity in women with other hepatic disorders in pregnancy would be useful. The significant percentage of women in this audit with a history of allergy/atopy is interesting, and investigation of other populations with ICP to examine a possible association would be worthwhile.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval

Research approval was provided by the Queensland Government Health Research Ethics and Governance Office (HREC/17/QGC/264). Patient consent was not required for ethical approval.

Guarantor

AM

Contributorship

AM and JL acquired, analysed, and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Westbrook RH, Dusheiko G, Williamson C. Pregnancy and liver disease. J Hepatol 2016; 64: 933–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geenes V, Williamson C. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15: 2049–2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinefski M, Contin M, Lucangioli S, et al. In search of an accurate evaluation of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Scientifica 2012; 2012: 496489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castano G, Lucangioli S, Sookoian S, et al. Bile acid profiles by capillary electrophoresis in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Clin Sci 2006; 110: 459–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng D, He W. Asymptomatic elevated total serum bile acids representing an unusual form of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2016; 134: 343–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang WM, Gowda M, Donnelly JG. Bile acid ratio in diagnosis of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Am J Perinatol 2009; 26: 291–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kremer AE, Bolier R, Dixon PH, et al. Autotaxin activity has a high accuracy to diagnose intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. J Hepatol 2015; 62: 897–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kenyon AP, Piercy CN, Girling J, et al. Pruritus may precede abnormal liver function tests in pregnant women with obstetric cholestasis: a longitudinal analysis. BJOG 2001; 108: 1190–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nezer MCY, Drukker L, Farkash R, et al. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: does bile acid levels really matter? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017; 216: S445–SS46. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kenyon AP, Tribe RM, Nelson-Piercy C, et al. Pruritus in pregnancy: a study of anatomical distribution and prevalence in relation to the development of obstetric cholestasis. Obstet Med 2010; 3: 25–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oeda S, Takahashi H, Yoshida H, et al. Prevalence of pruritus in patients with chronic liver disease: a multicenter study. Hepatol Res 2018; 48: E252–EE62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neale G, Lewis B, Weaver V, et al. Serum bile acids in liver disease. Gut 1971; 12: 145–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Puri PDK, Joyce A, Mirshahi F, et al. The presence and severity of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is associated with specific changes in circulating bile acids. Hepatology 2018; 67: 534–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eisendle K, Muller H, Ortner E, et al. Pruritus of unknown origin and elevated total serum bile acid levels in patients without clinically apparent liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 26: 716–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kong X, Kong Y, Zhang F, et al. Evaluating the effectiveness and safety of ursodeoxycholic acid in treatment of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: a meta-analysis (a prisma-compliant study). Medicine 2016; 95: e4949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bacq Y, Sentilhes L, Reyes HB, et al. Efficacy of ursodeoxycholic acid in treating intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2012; 143: 1492–1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]