Abstract

Background

Clinical practice guidelines for treating tobacco use and lung cancer screening guidelines recommend smoking cessation counseling to current smokers by health care professionals.

Objective

Our objective was to determine the contemporary patterns of current smokers’ discussions about smoking with their health care professionals in the USA.

Design, Setting, and Participants

We conducted an observational study of 30,132 current smokers (weighted sample 40,126,006) for the years 2011 to 2015 using data from the National Health Interview Survey.

Main Measures

Our main outcome was the proportion of current smokers who had discussions about smoking with their health care professionals. We used the Cochran-Armitage trend test to evaluate the temporal trends in current smokers’ discussions about smoking, and used a multivariable logistic model to determine the predictors of discussions about smoking, controlling for smokers’ demographics, health status, and receipts of lung cancer screening.

Key Results

Our study found the proportion of current smokers who had discussions about smoking with their health care professionals increased from 51.3% in 2011 to 55.4% in 2015 (P-trend < 0.0001). However, about 15% of current smokers who underwent lung cancer screening did not have or could not recall discussions about smoking with their health care professionals. In multivariable analyses and sensitivity analysis, the predictors of discussions about smoking were being a heavy smoker, receipt of lung cancer screening, being non-Hispanic white, having a physician office visit in the past year, being diagnosed with respiratory conditions, having fair or poor health, and having insurance coverage.

Conclusions

The results demonstrated a steady but slow increase in current smokers’ discussions about smoking with their health care professionals in recent years, especially among heavy smokers. More than 40% of current smokers did not have or could not recall any discussions about smoking with their health care professionals.

KEY WORDS: current smoker, communication, smoking, lung cancer screening

INTRODUCTION

Since the first Surgeon General’s Report on Smoking and Health in 1964,1 the prevalence of smoking has dropped from a projected 51.1 to 15.1% in 2015.2, 3 However, smoking remains the leading preventable cause of mortality in the USA4 and causes a substantial economic burden to society.4, 5 In recent years, many changes in healthcare policy, clinical practice guidelines, and intensive media campaigns have promoted discussions about smoking with health care professionals. Such initiatives include the updated 2010 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) memo on counseling to prevent tobacco use, which extended insurance coverage of smoking cessation counseling to asymptomatic Medicare beneficiaries6 and the 2011 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act which required full coverage for smoking cessation services.7 The 2011–2016 “meaningful use of certified electronic health records” policy required health care providers to document smoking status for more than 50% of patients aged 13 years or older in phase I and 80% in phase II.8 Also, there were substantial media campaigns related to smoking around the 50th anniversary of the 1964 release of the first Surgeon General’s Report.1, 4 Furthermore in 2015, CMS issued a decision memo on promoting the promising lung cancer screening (LCS) using low-dose computed tomography scans, which required shared decision-making between physicians and patients, including a discussion on the importance of smoking cessation.9

The impact of these policy changes and media campaigns on discussions about smoking among the general population and vulnerable sub-populations remains uncertain, however. It is important to understand the changes in the patterns of patient-provider discussions about smoking among specific subgroups of current smokers who have a high prevalence of smoking but who are less likely to quit, for instance, those with low socioeconomic status, those with no insurance, and minorities.10–13 Even for current smokers who had discussions about smoking with their physicians, they may not be able to recall their conversations, particularly if discussions about smoking were very brief with insufficient intensity.14, 15 Findings from previous studies have shown significant variation in the rates of patient-provider discussions about smoking among adults across different settings.16–18 A study in Minnesota reported that 51.3% current smokers had been asked about tobacco use or advised to quit,19 a rate similar to the that reported in a study using the 2010 National Health Interview Survey data.20 Another study used National Adult Tobacco Survey found that the 65.8% current cigarette smokers were advised to quit.21 The reported prevalence of smoking cessation counseling was high in nine nonprofit HMOs participating National Cancer Institute-funded Cancer Research Network, 90% of smokers were asked about smoking, 71% were advised to quit.16

This study was designed to provide a population-based estimate of the prevalence of patient-provider discussions about smoking among current smokers using contemporary national survey data. Furthermore, we determined whether the rates of discussions about smoking differed by patient demographic factors, especially among minority groups and the uninsured population. The CMS decision memo on promoting the LCS and the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)’s grade B recommendation on the LCS may have affected the rate of smoking cessation counseling. Therefore, we also sought to determine whether the CMS and USPSTF endorsing LCS were associated with any trends in rates of physician-patient discussions about smoking.

METHODS

Data

We analyzed data from the 2011 to 2015 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). Initiated in 1957 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the NHIS is one of the largest in-person household health survey databases of non-institutionalized civilians in the USA. The survey is administered by the US Census Bureau with an oversampling of minority groups, including Hispanics, African Americans, and Asian Americans for better representativeness of the survey population. The NHIS collects information each year on various health-related topics and provides data for the purpose of monitoring healthcare trends and conducting research to determine contemporary health issues and to improve access to appropriate health care.

Study Population

We limited our analytic sample to respondents who were aged 18 years and older and were current smokers, because questions on discussions about smoking were only applicable to this subset of respondents. We excluded respondents who did not answer the question on the discussions about smoking with health care professionals (N = 23, 0.07% of study sample) since we were not sure whether these respondents had a discussion on smoking or not. We also excluded individuals with responses of “refused” (N = 517, 1.68%) and “not ascertained” (N = 22, 0.07%) to this question because for these respondents the survey process was likely discontinued prior to these questions ever being asked.

Predictors and Outcomes of Interest

The outcome of interest was whether current smokers and their physicians or other health care professionals discussed smoking with them in the past 12 months at the time of survey: “During the past 12 months, has a doctor or other health professional talked to you about your smoking?” To explore predictors associated with discussions about smoking, we obtained and constructed the following variables from the NHIS data: age, sex, race/ethnicity, employment status, insurance, education level, secondhand smoke exposure, personal history of cancer, respiratory conditions, having activity limitations due to lung/breathing problems, health status, access to healthcare resources, and number of office visits to doctors or other health professionals in the past year. Because the recent CMS coverage for LCS requires physicians to offer smoking cessation consultation to LCS-eligible smokers, we also stratified current smokers based on their eligibility for LCS to determine the impact of the recent LCS policy: LCS eligibility criteria included an age range of 55–77 years and at least a 30-pack-year smoking history; all others were considered ineligible.

Statistical Analysis

We assessed whether the demographic and health characteristics of respondents differed by the receipt of discussions about smoking using the Pearson chi-square test. We used the Cochran-Armitage trend test to evaluate the temporal trends in discussions about smoking over the study period. To examine the factors associated with discussions about smoking among current smokers, we created a multivariable logistic model controlled for statistically significant or clinically meaningful characteristics using the SURVEYLOGISTIC procedure. We further stratified respondents by insurance status, age, and race/ethnicity. Within each subgroup, we compared the receipt of discussions about smoking using the SURVEYFREQ procedure with a Rao-Scott chi-square test. We used NHIS analytic weights to account for the multistage sample design. Statistical significance was defined as a P value less than 0.01. Statistical analysis was conducted with SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC). This study was considered exempt from the Institutional Review Board at the University of Florida.

RESULTS

The analytic sample consisted of 30,132 current smokers (weighted sample size 40,126,006). Table 1 provides the baseline characteristics and demographics of current smokers from 2011 to 2015, stratified by whether they discussed smoking with a health care professional. As shown in Table 1, most current smokers who had discussed about smoking with a health care professional were aged 55 years or older (55 to 64 years old, 63.9%; 65 to 74 years old, 67.4%; and 75+ years, 64.5%), female (59.2%), non-Hispanic white (54.7%), had higher education (bachelor’s degree or higher 54.6%), were covered by public insurance (65.4%), had access to a usual source of health care other than the emergency room (62.0%), visited a physician’s office more often (1 visit, 49.6%; 2 to 5 visits, 68.2%; 6+ visits, 76.2%), and were diagnosed with respiratory diseases (all p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of Adults Who Had a Discussion with a Health Care Professional About Smoking: National Health Interview Survey 2010–2015

| Receipt of discussion about smoking | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||||

| Characteristics | Total no. | Weighted frequency | No. | % | No. | % | P value |

| Overall | 30,132 | 40,126,006 | 15,970 | 53.0 | 14,162 | 47.0 | |

| Age, years | < .0001 | ||||||

| 18–39 | 11,896 | 17,286,062 | 5123 | 43.0 | 6773 | 57.0 | |

| 40–54 | 9176 | 12,688,393 | 4969 | 54.6 | 4207 | 45.4 | |

| 55–64 | 5491 | 6,559,683 | 3503 | 63.9 | 1988 | 36.1 | |

| 65–74 | 2684 | 2,724,692 | 1808 | 67.4 | 876 | 32.6 | |

| 75+ | 885 | 867,175 | 567 | 64.5 | 318 | 35.5 | |

| Sex | < .0001 | ||||||

| Male | 15,506 | 21,895,431 | 7280 | 46.3 | 8226 | 53.7 | |

| Female | 14,626 | 18,230,575 | 8690 | 59.2 | 5936 | 40.8 | |

| Race/ethnicity | < .0001 | ||||||

| NH White | 20,008 | 29,328,804 | 11,022 | 54.7 | 8986 | 45.3 | |

| NH Black | 4921 | 5,009,075 | 2796 | 51.8 | 2125 | 48.2 | |

| Hispanic | 3645 | 4,093,862 | 1443 | 37.3 | 2202 | 62.7 | |

| NH Other | 1558 | 1,694,265 | 709 | 44.8 | 849 | 55.2 | |

| Currently employed | < .0001 | ||||||

| No | 13,027 | 16,401,781 | 7868 | 58.9 | 5159 | 41.1 | |

| Yes | 17,105 | 23,724,225 | 8102 | 47.5 | 9003 | 52.5 | |

| Education | 0.0003 | ||||||

| Less than high-school graduate | 6121 | 7,781,979 | 3149 | 49.6 | 2972 | 50.4 | |

| High-school graduate/GED | 10,391 | 14,449,854 | 5358 | 51.0 | 5033 | 49.0 | |

| Some college/associate degree | 9909 | 13,010,939 | 5423 | 54.1 | 4486 | 45.9 | |

| Bachelor’s degree or more | 3711 | 4,883,234 | 2040 | 54.6 | 1671 | 45.4 | |

| NLST | < .0001 | ||||||

| Low | 14,129 | 17,809,998 | 8240 | 57.9 | 5889 | 42.1 | |

| High | 3444 | 4,187,043 | 2368 | 69.5 | 1076 | 30.5 | |

| Unknown | 12,559 | 18,128,965 | 5362 | 42.6 | 7197 | 57.4 | |

| Attempted to quit smoking in the last 12 months (current smokers) | < .0001 | ||||||

| No | 15,766 | 21,113,412 | 7701 | 48.0 | 8065 | 52.0 | |

| Yes | 14,346 | 18,989,630 | 8258 | 56.9 | 6088 | 43.1 | |

| Personal history of cancer other than lung | < .0001 | ||||||

| No | 27,994 | 37,502,079 | 14,459 | 51.0 | 13,535 | 49.0 | |

| Yes | 2138 | 2,623,927 | 1511 | 68.4 | 627 | 31.6 | |

| Respiratory conditions diagnosed by a health professional | < .0001 | ||||||

| None | 23,776 | 32,020,873 | 11,695 | 48.7 | 12,081 | 51.3 | |

| Any | 6356 | 8,105,134 | 4275 | 65.9 | 2081 | 34.1 | |

| Emphysema (ever) | < .0001 | ||||||

| No | 28,773 | 38,537,035 | 14,861 | 51.0 | 13,912 | 49.0 | |

| Yes | 1359 | 1,588,972 | 1109 | 80.9 | 250 | 19.1 | |

| Asthma (ever) | < .0001 | ||||||

| No | 25,605 | 34,324,387 | 13,085 | 50.6 | 12,520 | 49.4 | |

| Yes | 4527 | 5,801,620 | 2885 | 61.8 | 1642 | 38.2 | |

| Asthma (attack in past 12 months) | < .0001 | ||||||

| No | 28,646 | 38,291,440 | 14,899 | 51.3 | 13,747 | 48.7 | |

| Yes | 1486 | 1,834,567 | 1071 | 70.4 | 415 | 29.6 | |

| Chronic bronchitis (past 12 months) | < .0001 | ||||||

| No | 27,816 | 37,304,742 | 14,163 | 50.2 | 13,653 | 49.8 | |

| Yes | 2316 | 2,821,265 | 1807 | 78.0 | 509 | 22.0 | |

| Activity limitations due to lung/breathing problem | < .0001 | ||||||

| No | 28,824 | 38,587,353 | 14,898 | 51.0 | 13,926 | 49.0 | |

| Yes | 1308 | 1,538,653 | 1072 | 80.9 | 236 | 19.1 | |

| General health status | < .0001 | ||||||

| Excellent/very good/good | 23,251 | 32,030,635 | 11,256 | 48.0 | 11,995 | 52.0 | |

| Fair/poor | 6881 | 8,095,371 | 4714 | 68.6 | 2167 | 31.4 | |

| Insurance status | < .0001 | ||||||

| Uninsured | 7626 | 10,126,837 | 2458 | 31.9 | 5168 | 68.1 | |

| Public only | 9170 | 10,413,736 | 6099 | 65.4 | 3071 | 34.6 | |

| Private | 13,167 | 19,277,044 | 7326 | 55.7 | 5841 | 44.3 | |

| Usual source of health care other than ER | < .0001 | ||||||

| No | 7434 | 10,203,591 | 1751 | 23.3 | 5683 | 76.7 | |

| Yes | 22,698 | 29,922,415 | 14,219 | 62.0 | 8479 | 38.0 | |

| Number of office visits to doctor or other health professional in last year | < .0001 | ||||||

| 0 | 7805 | 10,780,717 | 1057 | 13.1 | 6748 | 86.9 | |

| 1 | 4795 | 6,511,212 | 2403 | 49.6 | 2392 | 50.4 | |

| 2–5 | 10,308 | 13,756,176 | 6993 | 68.2 | 3315 | 31.8 | |

| 6+ | 7224 | 9,077,900 | 5517 | 76.2 | 1707 | 23.8 | |

LCS lung cancer screening, NH non-Hispanic, GED general education development

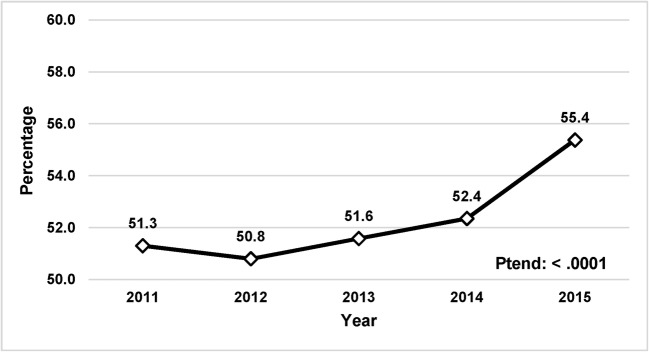

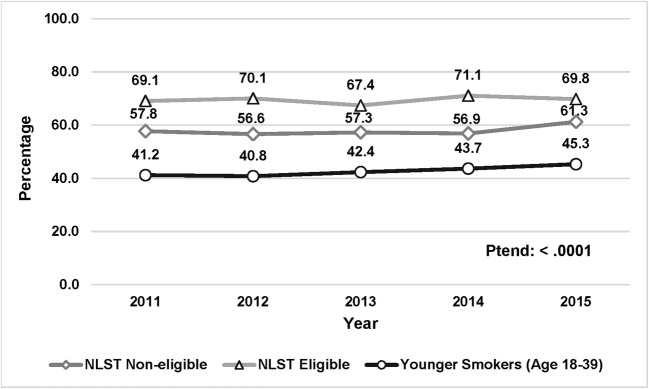

The frequency of discussions about smoking among current smokers increased slightly from 51.3% in 2011 to 55.4% in 2015 (P-trend < 0.0001) (Fig. 1). However, the growth rate was low for the first 4 years from 51.3% in 2011 to 52.4% in 2014 but rose significantly in 2015. When this trend was stratified by eligibility for LCS, we found that the proportion of current smokers who had discussions about smoking with health care professionals was greater among LCS-eligible individuals compared with those not eligible, 69.5% vs. 57.9% (Fig. 2). The significant increase in the proportion of discussions about smoking was observed in younger smokers aged 18–39 who were LCS non-eligible, from 41.2 to 45.3% (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Trends in the proportion of smokers who had discussions with their health care professional about smoking between 2011 and 2015: National Health Interview Survey.

Figure 2.

Trends in the proportion of smokers who had discussions with their health care professional about smoking, stratified by eligibility for lung cancer screening between 2011 and 2015: National Health Interview Survey.

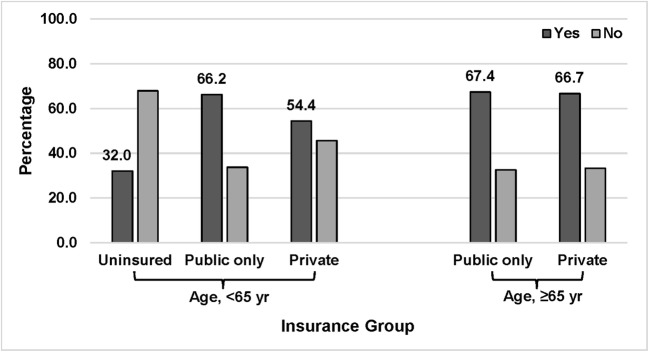

In the analysis using smokers who underwent LCS using either CT scans or chest X-rays (only 2015 NHIS provided information on receipt of LCS), the rates of discussions about smoking were 84.0% for those who received CT scans and 86.0% for those who received chest X-rays. In the subgroup analysis, the study sample was stratified by age group and insurance status. Among those who were 65 years or younger, the rate of discussions about smoking was lowest among those with no insurance coverage (32.0%); the rates were higher (54.4%) among those with private insurance, and highest among those with public insurance coverage (66.2%). For smokers older than 65, the rates of discussion about smoking were similar between samples with public insurance coverage (67.4%) and those with both public insurance and private complementary insurance coverage (66.7%) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

The proportion of smokers who had discussions with their health care professional about smoking, stratified by age group and insurance status: National Health Interview Survey 2011–2015.

In the multivariable analysis, those surveyed in 2015 were more likely to have discussed smoking with their health care professionals (odds ratio [OR] 1.16, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.04–1.30 for 2015 vs. the referent group in 2011). Those in the analytic sample who met the LCS eligibility criteria also had higher odds of having had a discussion about smoking (OR 1.53; 95% CI 1.32–1.77; P < .001) (Table 2). The other factors associated with discussions about smoking were younger age, being non-Hispanic white, having a quit attempt in the past year, a diagnosis of a respiratory condition, having chronic bronchitis, having an activity limitation due to lung/breath problem, reporting fair or poor health, having public or private insurance coverage, having a usual source of health care other than the emergency room, and having visited a doctor or other health care professional more often in the past year.

Table 2.

Weighted Logistic Regression Analysis Examining Patient-Provider Discussions About Smoking

| Receipt of discussion about smoking | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Year of survey | ||||

| 2011 | 1.00 | |||

| 2012 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 1.11 | 0.957 |

| 2013 | 1.06 | 0.95 | 1.18 | 0.337 |

| 2014 | 1.06 | 0.94 | 1.20 | 0.345 |

| 2015 | 1.16 | 1.04 | 1.30 | 0.009 |

| LCS eligibility | ||||

| Non-eligible (low-risk smoke) | 1.00 | |||

| Eligible | 1.53 | 1.32 | 1.77 | < .001 |

| Unknown | 0.30 | 0.24 | 0.38 | < .001 |

| Age, years | ||||

| 18–39 | 1.00 | |||

| 40–54 | 0.42 | 0.32 | 0.54 | < .001 |

| 55–64 | 0.42 | 0.32 | 0.54 | < .001 |

| 65–74 | 0.38 | 0.29 | 0.50 | < .001 |

| 75+ | 0.34 | 0.25 | 0.46 | < .001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1.00 | |||

| Female | 1.07 | 0.99 | 1.14 | 0.087 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 1.00 | |||

| Black | 0.96 | 0.86 | 1.06 | 0.404 |

| Hispanic | 0.68 | 0.61 | 0.76 | < .001 |

| Other | 0.83 | 0.69 | 1.00 | 0.046 |

| Currently employed | ||||

| No | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 1.00 | 0.92 | 1.10 | 0.928 |

| Education | ||||

| Less than high-school graduate | 1.00 | |||

| High-school graduate/GED | 1.01 | 0.91 | 1.12 | 0.915 |

| Some college/associate degree | 0.99 | 0.88 | 1.12 | 0.883 |

| Bachelor’s degree or more | 0.91 | 0.79 | 1.04 | 0.158 |

| Attempted to quit smoking in the last 12 months (current smokers) | ||||

| No | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 1.45 | 1.34 | 1.57 | < .001 |

| Personal history of cancer other than lung | ||||

| No | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 1.06 | 0.91 | 1.25 | 0.454 |

| Respiratory conditions diagnosed by a health professional | ||||

| None | 1.00 | |||

| Any | 1.34 | 1.00 | 1.79 | 0.049 |

| Emphysema (ever) | ||||

| No | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 1.24 | 0.91 | 1.68 | 0.174 |

| Asthma (ever) | ||||

| No | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 0.84 | 0.64 | 1.11 | 0.219 |

| Asthma (attack in past 12 months) | ||||

| No | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 1.08 | 0.86 | 1.35 | 0.512 |

| Chronic bronchitis (past 12 months) | ||||

| No | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 1.52 | 1.20 | 1.93 | < .001 |

| Activity limitations due to lung/breathing problem | ||||

| No | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 1.70 | 1.34 | 2.15 | < .001 |

| General health status | ||||

| Excellent/very good/good | 1.00 | |||

| Fair/poor | 1.27 | 1.15 | 1.41 | < .001 |

| Insurance status | ||||

| Uninsured | 1.00 | |||

| Public only | 1.41 | 1.25 | 1.59 | < .001 |

| Private | 1.23 | 1.11 | 1.35 | < .001 |

| Usual source of health care other than ER | ||||

| No | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 1.90 | 1.73 | 2.09 | < .001 |

| Number of office visits to doctor or other health professional in last year | ||||

| 0 | 1.00 | |||

| 1 | 5.35 | 4.69 | 6.09 | < .001 |

| 2–5 | 9.60 | 8.43 | 10.93 | < .001 |

| 6+ | 11.72 | 10.21 | 13.44 | < .001 |

LCS lung cancer screening, NH non-Hispanic, GED general education development

DISCUSSION

In a nationally representative sample of adult smokers, we found that the prevalence of discussions about smoking with health care professionals experienced a low growth rate from 51.3% in 2011 to 52.4% in 2014, but at a higher growth rate from 52.4% in 2014 to 55.4% in 2015 Additionally, current smokers who received LCS via either CT scans or chest X-rays had the highest rate of discussions about smoking than all other smokers. Among racial/ethnic groups, the prevalence of discussions about smoking was significantly lower among Hispanics than among smokers in other racial/ethnic groups. It is worth to note that the prevalence rates between non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic black smokers were comparable.

Our finding of 15% of current smokers who underwent LCS did not have a discussion about smoking with their health care professionals raises the possibility that these smokers actually had a conversation on smoking with their physicians who prescribed LCS but cannot recall it ever happened. Since smoking is the top factor contributing to 80 to 90% of lung cancer cases, therefore, both CMS and the USPSTF required that not only a brief recoding of smoking status but also a smoking cessation counseling and intervention should be integrated into the LCS program before smokers undergo LCS.9 The clinical guidelines and reimbursement policies for LCS consistently stated that smoking cessation cannot be replaced by low-dose CT scans and that smoking cessation should still be the priority for all current smokers.9, 22–24 Even though the 2011 National Lung Screening Trial results showed that lung cancer screening using low-dose CT scans could reduce cancer mortality by 20% compared with ineffective chest X-rays,25 smoking cessation is still more effective and cost-effective than LCS in reducing lung cancer mortality. As shown in our study that many LCS recipient could not recall the discussion about smoking, there is a clear need for effective ways to deliver smoking cessation services along with LCS.26, 27

Our study adds valuable information on further understanding racial disparities involved in the prevalence of discussions about smoking with health care professionals. As indicated in our study, the gap between non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic blacks has been diminishing, while the gap between non-Hispanics and Hispanics persisted. In many previous studies that utilized national survey data, the gap found between non-Hispanics and Hispanic groups was mostly larger than that between non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic blacks.28, 29 English language proficiency was once considered a major barrier for Hispanics to discuss their smoking behavior. The values and beliefs of the culture, as well as social norms, may have also led to a lower rate of discussions about smoking among the Hispanic population. However, there is no doubt that having a discussion about smoking with health care professionals is the first step to increasing current smokers’ motivation to quit and also increasing the odds of successful cessation30–33; therefore, to control the smoking-related burden among the Hispanic population, more efforts are needed to promote discussions about smoking in this ethnic group.

We noted a significantly improved rate for discussions about smoking among respondents with insurance coverage. Curry et al. have reported variations in the use of smoking cessation services across four different types of health insurance and found that the use of smoking cessation services was highest among current smokers with full insurance coverage.34 The recent Medicaid healthcare expansion program under the Affordable Care Act offers insurance coverage for many previously uninsured smokers and is expected to increase the use of smoking cessation services in this population.35–37 This expanded insurance coverage may also increase the number of physician office visits. As shown in our study, the number of physician office visits is another factor associated with higher odds of physician-patient discussion about smoking.

Our study is subject to limitations. The NHIS question on the presence of discussions about smoking with health care professionals was vague, and this discussion might have been very brief. An effective discussion on smoking involves various components that were not captured in the survey. In addition, the NHIS is a cross-sectional survey that does not follow up with the respondents after the initial survey. The effect of discussions about smoking thus is unknown, and the impact of increased prevalence of discussions about smoking on the rate of smoking cessation in the general population is uncertain.38 Additionally, the cross-sectional data also limit the capability to conclude causal relationships between receipt of LCS and discussions about smoking. The survey on smoker self-reported discussions could be biased due to recall problems, and this issue may be addressed in the future using other data sources such as the electronic health record data. For non-native English speakers, language can also be a barrier to effective discussions on smoking and therefore respondents may be less likely to correctly recall the intent of the conversation. This issue may be more severe for Hispanics. Moreover, some smokers may have quit smoking after the discussion on smoking with health care professionals in the past 12 months. The NHIS survey did not ask this question to the smokers who recently quit smoking and it is likely that effective counseling by their doctor or health professional may have depressed the actual percentage of smokers who discussed smoking during the past 12 months.

In conclusion, using a nationally representative population, our study determined the prevalence of discussions about smoking among current smokers over 5 years. We found a steady increase and a significant rise in these discussions among smokers in recent years, and especially among smokers who underwent LCS. However, more than 40% of current smokers did not have discussions about smoking with their health care professionals or cannot recall they ever had this discussion. Importantly, our study demonstrated significant ethnic disparities in discussions about smoking with health care professionals. However, the barriers to minority smokers engaging in smoking-related discussions is still unknown. Herein, to maximize the benefits of these recent policy changes and media campaigns on smoking cessation and to reduce smoking-related societal and economic burden, more health promotion programs are needed to engage current smokers from vulnerable populations in discussions about smoking with their health care professionals. Future policy efforts should also address these persistent gaps.

Funders

The study was supported by the University of Florida Health Cancer Center Research Pilot Grant through the Florida Consortium of National Cancer Institute Centers Program at the University of Florida (Dr. Huo and Dr. Bian).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the UF Health Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Smoking and health: report of the advisory committee to the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service (Report No. 1103). Washington DC: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, CDC; 1964.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults in the United States. Atlanta: Office on Smoking and Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holford TR, Meza R, Warner KE, Meernik C, Jeon J, Moolgavkar SH, et al. Tobacco control and the reduction in smoking-related premature deaths in the United States, 1964-2012. JAMA. 2014;311(2):164–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.285112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014.

- 5.Xu X, Bishop EE, Kennedy SM, Simpson SA, Pechacek TF. Annual healthcare spending attributable to cigarette smoking: an update. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(3):326–33. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National Coverage Determination (NCD) for Counseling to Prevent Tobacco Use (210.4.1). 2010. [PubMed]

- 7.Final Update Summary. Tobacco Smoking Cessation in Adults, Including Pregnant Women: Behavioral and Pharmacotherapy Interventions. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force; 2015. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions. Accessed Feb 22 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Health information technology (Health IT). EHR incentives and certification. 2013. https://www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/how-attain-meaningful-use. Accessed Feb 22 2019.

- 9.Decision Memo for Screening for Lung Cancer with Low Dose Computed Tomography (LDCT) (CAG-00439N). Baltimore, MD: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2015.

- 10.Barbeau EM, Krieger N, Soobader MJ. Working class matters: socioeconomic disadvantage, race/ethnicity, gender, and smoking in NHIS 2000. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(2):269–78. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laveist TA, Thorpe RJ, Jr, Mance GA, Jackson J. Overcoming confounding of race with socio-economic status and segregation to explore race disparities in smoking. Addiction. 2007;102(Suppl 2):65–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Novotny TE, Warner KE, Kendrick JS, Remington PL. Smoking by blacks and whites: socioeconomic and demographic differences. Am J Public Health. 1988;78(9):1187–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.9.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lantz PM, House JS, Lepkowski JM, Williams DR, Mero RP, Chen J. Socioeconomic factors, health behaviors, and mortality: results from a nationally representative prospective study of US adults. JAMA. 1998;279(21):1703–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Folsom AR, Grimm RH., Jr Stop smoking advice by physicians: a feasible approach? Am J Public Health. 1987;77(7):849–50. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.77.7.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szatkowski L, McNeill A, Lewis S, Coleman T. A comparison of patient recall of smoking cessation advice with advice recorded in electronic medical records. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):291. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quinn VP, Stevens VJ, Hollis JF, Rigotti NA, Solberg LI, Gordon N, et al. Tobacco-cessation services and patient satisfaction in nine nonprofit HMOs. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(2):77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conroy MB, Majchrzak NE, Regan S, Silverman CB, Schneider LI, Rigotti NA. The association between patient-reported receipt of tobacco intervention at a primary care visit and smokers’ satisfaction with their health care. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7(Suppl 1):S29–34. doi: 10.1080/14622200500078063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thorndike AN, Regan S, Rigotti NA. The treatment of smoking by US physicians during ambulatory visits: 1994 2003. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(10):1878–83. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.092577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Solberg LI, Boyle RG, Davidson G, Magnan SJ, Carlson CL, eds. Patient satisfaction and discussion of smoking cessation during clinical visits. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Elsevier; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Kruger J, Shaw L, Kahende J, Frank E. Health care providers’ advice to quit smoking, National Health Interview Survey, 2000, 2005, and 2010. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E130-E. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.110340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King BA, Dube SR, Babb SD, McAfee TA. Patient-reported recall of smoking cessation interventions from a health professional. Prev Med. 2013;57(5):715–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wender R, Fontham ET, Barrera E, Jr, Colditz GA, Church TR, Ettinger DS, et al. American Cancer Society lung cancer screening guidelines. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(2):107–17. doi: 10.3322/caac.21172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lung Cancer. Screening. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force; 2013. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/lung-cancer-screening. Accessed Feb 22 2019.

- 24.Tanner NT, Kanodra NM, Gebregziabher M, Payne E, Halbert CH, Warren GW, et al. The Association between Smoking Abstinence and Mortality in the National Lung Screening Trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(5):534–41. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201507-1420OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Lung Screening Trial Research T. Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, Black WC, Clapp JD, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park ER, Gareen IF, Japuntich S, Lennes I, Hyland K, DeMello S, et al. Primary Care Provider-Delivered Smoking Cessation Interventions and Smoking Cessation Among Participants in the National Lung Screening Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(9):1509–16. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pedersen JH, Tonnesen P, Ashraf H. Smoking cessation and lung cancer screening. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4(8):157. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.03.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National Healthcare Quality & Disparities Reports. Rockville, MD; 2013. https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/index.html. Accessed 22 Feb 2019.

- 29.Houston TK, Scarinci IC, Person SD, Greene PG. Patient smoking cessation advice by health care providers: the role of ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and health. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(6):1056–61. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.039909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fiore M. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update: Clinical practice guideline. Diane Publishing; 2008.

- 31.Wu D, Ma GX, Zhou K, Zhou D, Liu A, Poon AN. The effect of a culturally tailored smoking cessation for Chinese American smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(12):1448–57. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stead LF, Buitrago D, Preciado N, Sanchez G, Hartmann-Boyce J, Lancaster T. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(5):CD000165. 10.1002/14651858.CD000165.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Kotz D, Brown J, West R. ‘Real-world’ effectiveness of smoking cessation treatments: a population study. Addiction. 2014;109(3):491–9. doi: 10.1111/add.12429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Curry SJ, Grothaus LC, McAfee T, Pabiniak C. Use and cost effectiveness of smoking-cessation services under four insurance plans in a health maintenance organization. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(10):673–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809033391006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bailey SR, Hoopes MJ, Marino M, Heintzman J, O'Malley JP, Hatch B, et al. Effect of Gaining Insurance Coverage on Smoking Cessation in Community Health Centers: A Cohort Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(10):1198–205. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3781-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Land T, Warner D, Paskowsky M, Cammaerts A, Wetherell L, Kaufmann R, et al. Medicaid coverage for tobacco dependence treatments in Massachusetts and associated decreases in smoking prevalence. PLoS One. 2010;5(3):e9770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greene J, Sacks RM, McMenamin SB. The impact of tobacco dependence treatment coverage and copayments in Medicaid. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(4):331–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boyle R, Solberg L, Fiore M. Use of electronic health records to support smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014(12). 10.1002/14651858.CD008743.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]