Abstract

Objectives. To estimate the number of lives saved from firearms suicide with expansions of gun restrictions based on mental health compared with the number who would be unnecessarily restricted.

Methods. Agent-based models simulated effects on suicide mortality resulting from 5-year ownership disqualifications in New York City for individuals with any psychiatric hospitalization and, more broadly, anyone receiving psychiatric treatment.

Results. Restrictions based on New York State Office of Mental Health–identified psychiatric hospitalizations reduced suicide among those hospitalized by 85.1% (95% credible interval = 36.5%, 100.0%). Disqualifications for anyone receiving psychiatric treatment reduced firearm suicide rates among those affected and in the population; however, 244 820 people were prohibited from firearm ownership who would not have died from firearm suicide even without the policy.

Conclusions. In this simulation, denying firearm access to individuals in psychiatric treatment reduces firearm suicide among those groups but largely will not affect population rates. Broad and unfeasible disqualification criteria would needlessly restrict millions at low risk, with potential consequences for civil rights, increased stigma, and discouraged help seeking.

In 2016, 44 965 individuals died by suicide in the United States.1 As many other leading causes of mortality have decreased in recent decades, the suicide rate has increased by more than 30% since 1999.2 Firearm-related suicide, in particular, along with the greater burden of firearm violence,3 remains a leading cause of death among those aged 10 to 54 years.4 The population-wide increase in firearm suicide deaths in the United States warrants a public health response. However, empirical data to evaluate different approaches to suicide prevention in the population are limited.

Mental illness is a key reason that many people attempt suicide,5,6 and access to a firearm is often the reason they die; guns are a highly lethal method of intentional self-injury.7,8 Thus, restricting access to firearms for people at risk for suicide, including many with serious mental illnesses, can save many lives.9–12 Gun prohibition linked specifically to involuntary psychiatric hospitalization is a longstanding federal policy. However, the fact that most gun suicide decedents have never been involuntarily hospitalized limits the effectiveness of point-of-sale prohibitions that are predicated on civil commitment alone. Gun restrictions that have been proposed or enacted have included people with records of any (voluntary or involuntary) psychiatric hospitalization,13–15 and, indeed, a few states have broader criteria, such as having a record of any psychiatric hospitalization (Connecticut) or even a record of any mental health treatment (Hawaii).

Enforcement of gun prohibitions based on mental health treatment history alone, without the legal safeguards of an adjudicatory process, is problematic from both a practical and civil rights standpoint. An estimated 44.7 million US adults have a diagnosable mental illness, and about 43% of these individuals are receiving treatment.16 The large majority of people treated for a mental illness in the community will neither die of suicide nor perpetrate violent acts. Moreover, restrictions can have unintended consequences; mental illness remains a highly stigmatized condition.17 Restrictions on firearm access linked to mental illness services utilization per se could discourage help seeking, especially among gun owners who believe that receiving mental health treatment will result in loss of their gun rights. Furthermore, associations between gun violence and mental illness more generally are complex and imbued with a problematic social and political history linked with race/ethnicity and class disparities.18 Guiding policy on firearm ownership to reduce suicide must balance efficacy with fairness, the protection of civil rights, and the goal of reducing stigma attached to mental illness.

In this study, we simulated randomized trials to estimate the hypothetical population-level effects of firearm ownership disqualification policies based on mental health records. We began with a prohibition predicated on any psychiatric hospitalization—a criterion that is broader than the current federal restriction linked to involuntary commitment but that still affects only a small proportion of the population. We then broadened the range of individuals who would be disqualified and examined the effect of gun prohibition based on any mental health treatment. Our model thus allowed us to explore both the benefits and social costs of such a broad restriction—to estimate its effectiveness, but also the extent to which it would preemptively restrict the rights of millions of law-abiding, nondangerous people. We examined the potential effect of firearm ownership disqualifications on overall population rates of firearm-related suicide, and also the effect on the targeted population of restricted individuals considered as a discrete group.

METHODS

We developed an agent-based model simulating the dynamic processes contributing to firearm suicide among adults in New York City. Figure A (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) illustrates the relations included in the model.19–22 We used data from New York City sources to calibrate the model when possible; we also used national or other community-based data (see data sources in Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Additional details about model parameters and processes include a description of the model following the Overview, Design Concepts, Details protocol (Appendix A),23,24 initialization parameters and default values (Table B), and flow charts illustrating steps in the model (Figures B and C, available as supplements to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org), as well as final calibration formulae for key model parameters.

Agent Population and Neighborhoods

We initialized the population of 260 000 agents to approximate a 5% sample of the New York City adult population aged 18 to 64 years in the year 2000.19,20 Agent attributes included age, gender, race/ethnicity, income, and education, as well as agent behaviors including substance use, a range of psychiatric disorders, gun carrying and ownership, and suicidal behavior. We assigned agents to neighborhoods, proportionate to size; distributions of age, gender, race/ethnicity, and household income matched Census data for each of the 59 New York City community districts in 2000.25 We chose the year 2000 because most data used to parameterize agent behaviors were collected in the mid-2000s. Individual behaviors were influenced by neighborhood characteristics and vice versa. Also, the study period predates 2009, the year that New York State began reporting large numbers of gun-disqualifying mental health records to the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s National Instant Criminal Background Check System. As of 2017, the number of “adjudicated mental health” records from New York State that are active in the National Instant Criminal Background Check System Index exceeds 540 000.26 The impact that the presence of such records in the background check system may have had is unknown, but it would not have affected the data inputs to our models, in any case.

Aging, Mortality, Movement

Each model step represented 1 year in time. At each time step, agents aged by 1 year, a proportion of agents moved to a new neighborhood, and agents died consistent with 2000 New York City adult all-cause mortality rates.27 Agents’ probabilities of moving were based on income, current neighborhood duration of residence, and violent victimization at the last time step, calibrated with data from longitudinal studies in urban areas28 and the Panel Study of Income Dynamics.29

Gun Carrying and Ownership

Agents were calibrated to have firearms in their household and, separately, to carry firearms at each time step. We separated household guns and gun carrying to allow agents to access guns without legal purchase (e.g., in a nonlicensed or illegal market, or exchanged within their social network—for example, a firearm from family or a friend). We calibrated probabilities of household firearms and, separately, carrying from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication,30 which included separate questions on household firearms and firearm carrying within the past 30 days. Probabilities were based on demographics, past household firearms and carrying at previous time steps, history of victimization and perpetration, and substance use. Furthermore, we specified that agents who had social network ties to agents who had household firearms or carried them were able to use those guns. Thus, even when an agent was disqualified from gun purchasing, the agent was still able to access a firearm. Furthermore, we varied the prevalence of gun access through sensitivity analyses, especially as New York City is estimated to have lower gun ownership rates compared with the United States.

Psychiatric Disorders and Treatment

Agents also had the possibility of having 1 or more psychiatric disorders at each time step. We calibrated probabilities of having major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, antisocial behavior, intermittent explosive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, mania, and psychosis from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication.30 Probabilities at each time step were based on predictive equations as well as history of disorders at previous time steps.

At each time step, agents could receive mental health treatments, including overnight hospitalization, medication, and other treatments based on National Comorbidity Survey Replication calibration.

To measure the occurrence of psychiatric hospitalization, we used data from the Patient Characteristics Survey, a questionnaire that collects information on all individuals in the public mental health system in New York State, including those inpatients of state and locally operated psychiatric facilities.31,32 These data capture those inpatient stays that are reported to the New York State Office of Mental Health (OMH). We calibrated the number of OMH-identified psychiatric hospitalizations to match the total number of New York City adults who were hospitalized for psychiatric reasons (as identified by OMH), based on race/ethnicity, age, and borough.

Suicide and Other Health Outcomes Related to Firearms

At each time step, agents died by suicide with or without a firearm according to New York City Office of the Chief Medical Examiner data.33 We calculated probabilities based on race/ethnicity, gender, age, mental health and suicidal behavior, and drug and alcohol use.34,35 Suicide was influenced by history of suicide ideation and suicide attempt; agents could also die by suicide without previous ideation or attempt according to previous literature about impulsivity of suicide.10,36 Presence of a firearm increased the probability of a fatal suicide attempt.37 We also calculated probabilities of suicide ideation and attempt from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication.30 We based probabilities on sociodemographic characteristics, household firearm and carrying statuses, alcohol and drug use,38 history of violent victimization and perpetration,39 alcohol and drug abuse,38 each of the 7 mental health disorders listed previously, and mental health treatment.38,40

Social Network and Neighborhood Influences

We assigned each agent a target number of close social ties, with an average of 4 ties per agent.41 We matched agents on the basis of age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, firearm status (gun carrying and ownership), drinking status, and spatial proximity, such that agents who were more similar and geographically closer to each other were more likely to become social ties.41,42 Social network members matched to a particular agent at baseline remained part of that agent’s social network for the duration of the model run. On the basis of empirical social network literature,43 we modeled ties to other agents who were involved in gun violence, which informed suicide risk probabilities. The strength of the social network influence on model parameters was varied in sensitivity analyses (Appendix B, Table C, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Agents were also embedded in neighborhoods, and those neighborhoods had their own characteristics (e.g., demographics, average mental health and suicide, violence, and substance use). We used predictive equations to assess the strength of the relationship between neighborhood characteristics and suicide; the strength of the neighborhood relationships determined 10% of suicide risk; the remaining 90% was determined by individual-level risk factors. We then varied this distribution in sensitivity analyses (Appendix B).

Model Calibration and Intervention Scenarios

During model calibration, we compared agent-based model estimates with empirical data. We used an iterative process44 to adjust predictive equations and initial conditions in the model (Table 1).

TABLE 1—

Annualized Estimates of Suicide, Mental Health Treatment, and Firearm Carrying and Ownership From the Agent-Based Model and Empirical Data Sources in New York City When Available and the National Comorbidity Study Replication

| ABM Estimate (95% CI)a | Empirical Estimates | |

| Firearm-related suicide, rate/100[thin space]000 | 2.1 (1.9, 2.3) | 2.0b |

| Any psychiatric hospitalization, rate/100 000 | 108.3 (105.2, 110.9) | 108.0b |

| Any mental health treatment in past y, % | 13.9 (13.9, 14.0) | 15.8c |

| Firearm ownership, % | 24.3 (24.1, 24.4) | 24.0c |

| Firearm carrying status, % | 4.0 (3.9, 4.0) | 3.9c |

Note. ABM = agent-based model; CI = credible interval.

Median and 95% CI from 50 runs of ABM.

New York City Office of the Chief Medical Examiner (2000–2006). Treatment from NY State Office of Mental Health.

National Comorbidity Study Replication, 2001–2003.

After a burn-in period to stabilize estimates, we ran each model scenario 50 times for 30 years, and we report the median across runs; credible intervals (CIs) reflect variation across the 50 runs, which we varied in sensitivity analyses. To estimate the CI, we rank ordered the 50 estimates for each model run, and report the 2.5th and 97.5th percentile. We developed the model by using Recursive Porous Agent Simulation Toolkit for Java (RepastJ, version 3.0, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL), and implemented in Eclipse (version 4.2, Eclipse Foundation, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada). We implemented 2 ownership prohibitions; each year, an agent could meet disqualification criteria. Agents meeting criteria for each prohibition were restricted from gun ownership and purchasing for 5 years (based on the recommendation of the Consortium for Risk-Based Firearm Policy45); gun carrying remained possible for prohibited agents and was calibrated in the model as described previously. The first scenario was to disqualify those with OMH-identified inpatient hospitalization, as defined previously, and constituting 0.11% of the simulated population each year. The second scenario was to disqualify those with past-year mental health treatment, as defined previously, and constituting 13.9% of the simulated sample. We also estimated the number of individuals needed to “treat”: that is, the number that would be exposed to the ownership restriction for each suicide to be prevented, as 1 divided by the suicide rate after implementation of the ownership disqualification minus the rate prior. We multiplied those estimates by the prevalence of the high-risk groups to estimate the number of disqualified individuals needed to prevent each suicide. We considered high-risk groups to be (1) OMH-identified psychiatric hospitalizations and (2) those with any mental health treatment.

RESULTS

Table 1 describes the distribution of demographics and key parameters of interest at baseline and compares these distributions to empirical data sources. Table 2 provides an overall summary of model scenarios and estimated intervention effects, which are graphically depicted in Figures 1 and 2.

TABLE 2—

Simulation of Gun-Related Suicide in New York City After Implementation of Mental Illness Related Ownership Disqualifications Among the Total Agent Population and High-Risk Groups

| Rate per 100 000 (95% CI) | Percentage Decrease (95% CI) | |

| Among the total population | ||

| Baseline | 2.1 (1.9, 2.3) | |

| Ownership disqualification (5-y duration): OMH-identified psychiatric hospitalizations | 2.0 (1.8, 2.2) | 2.8 (–7.1, 14.5) |

| Any mental health treatment in past year | 0.8 (0.7, 1.0) | 59.8* (50.5, 64.8) |

| Among high-risk groups | ||

| OMH-identified psychiatric hospitalizations | ||

| Baseline | 15.8 (7.9, 25.9) | |

| 5-y restricted ownership | 2.4 (0.0, 10.0) | 85.1* (36.5, 100.0) |

| Any mental health treatment in past year | ||

| Baseline | 3.5 (3.0, 4.1) | |

| 5-y restricted ownership | 0.6 (0.5, 0.9) | 82.9* (76.1, 87.3) |

Note. CI = credible interval; OMH = Office of Mental Health.

P < .05 significant decrease.

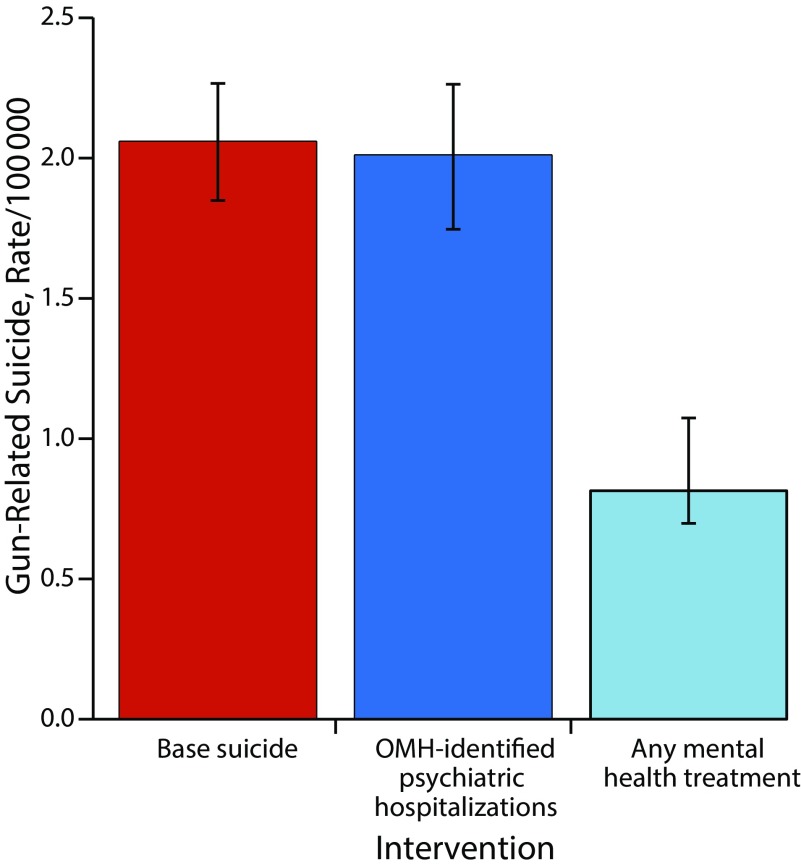

FIGURE 1—

Simulation of Gun-Related Suicide in New York City After Implementation of Mental Illness–Related Ownership Disqualifications

Note. OMH = Office of Mental Health. Based on a simulated sample of 260 000 residents of New York State.

FIGURE 2—

Simulation of Gun-Related Suicide in New York City After Implementation of Mental Illness–Related Ownership Disqualifications, by Targeted High-Risk Subpopulation

Note. OMH = Office of Mental Health.

Effects of Firearm Disqualification

Population rates of firearm suicide.

The average annual baseline rate of firearm-related suicide was 2.1 per 100 000 (95% CI = 1.9, 2.3; lower in New York City than the national rate; Figure 1). Restricting firearm ownership based on OMH-identified psychiatric hospitalizations had no statistically significant influence on the rate of firearm-related suicide (2.0/100 000; 95% CI = 1.8, 2.2). Number-needed-to-treat analysis indicated that approximately 144 000 individuals need to be disqualified to prevent 1 suicide. Disqualifying anyone with mental health treatment significantly decreased the population firearm suicide rate in New York City to 0.8 per 100 000 (95% CI = 0.7, 1.0; a 59.8% [95% CI 50.5%, 64.8%] decrease). Number-needed-to-treat analysis indicated that approximately 724 000 individuals need to be disqualified to prevent 1 suicide.

Rates of firearm suicide among high-risk groups.

We next tested whether restrictions affected suicide rates among very-high-risk groups considered separately (Figure 2): (1) OMH-identified psychiatric hospitalizations and (2) those with any mental health treatment. Restrictions significantly influenced firearm-related suicide among both of the high-risk groups. Restrictions based on OMH-identified psychiatric hospitalizations reduced suicide in this population from 15.8 per 100 000 (95% CI = 7.9, 25.9) to 2.4 per 100 000 (95% CI = 0.0, 10.0; an 85.1% [95% CI = 36.5%, 100.0%] decrease). Restrictions based on any mental health treatment reduced suicide among those with any mental health treatment from 3.5 per 100 000 (95% CI = 3.0, 4.1) to 0.6 per 100 000 (95% CI = 0.5, 0.9; an 82.9% [95% CI = 76.1%, 87.3%] decrease).

Sensitivity Analysis

Our 10 sensitivity analyses are consistent with our main findings, suggesting that model findings for firearm-related suicide did not depend on the number of model runs, the size of the contribution of neighborhood and network characteristics, the prevalence of firearms in the home, or the prevalence of gun carrying. Please see Appendix B for specific results.

DISCUSSION

Firearm disqualification based on OMH-identified inpatient hospitalization did not significantly influence population rates of suicide, given the low prevalence of inpatient psychiatric treatment in the population. However, among those who were hospitalized, suicide rates decreased by 85%. Our agent-based model allowed us to estimate the potential efficacy of 2 different disqualification criteria and to demonstrate the minimum and maximum bounds of impact that disqualification criteria could have on population rates of suicide by firearms. Indeed, we estimated based on the simulation that to have a population impact on suicide rates, disqualifying individuals based on broad, largely unenforceable and unfeasible criteria such as presence in any psychiatric treatment would theoretically reduce firearm suicide rates by more than half, but at large societal costs. For every life saved, approximately 724 000 individuals would be identified and restricted needlessly; they would not have died from suicide even without the restriction. While policymakers have proposed such broad criteria, and some states have enacted such criteria, though enforcement remains equivocal, concerns about stigma and civil rights remain paramount.

Restricting firearm access to those with relatively rare treatment regimens such as OMH-identified inpatient hospitalization is a high-risk approach to public health,46 as control is concentrated among a small group of individuals among whom the burden of firearm injury is concentrated. While high-risk approaches are often efficacious in reducing burden among the affected groups,47,48 these approaches are limited in population-level impact by the small size of the high-risk group relative to the large population that is unexposed to the policy, including many at risk for other reasons. In the case of firearm suicide, criteria to disqualify individuals from gun ownership based on psychiatric hospitalization alone affect an exceedingly small group of individuals. Broader disqualification criteria would theoretically have a more significant effect in reducing suicide at the population level, but identification and enforcement are impractical.

Furthermore, such approaches would hardly be equitable. Embedded inequities—longstanding disparities in access to treatment—would be replicated in gun-disqualifying records. For example, while racial/ethnic minorities have less access to mental health care and receive lower-quality care,49,50 rates of involuntary psychiatric hospitalization and civil commitment are higher among racial minorities, including in New York State51; to the extent that such criteria are used for gun disqualification, those disparities will be reproduced in disqualification. Indeed, commonly held assumptions about mental illness and violence are historically embedded in race/ethnicity and class conflict, often based on untenable evidence,18 suggesting that expansions of gun disqualification on the basis of mental illness may exacerbate stigma linked to multiple marginalized social statuses. Further simulation modeling that assesses the potential unintended consequences on the emergence and exacerbation of disparities is an important gap in the literature for which agent-based modeling is well suited in future investigations.

Public health investments that have focused on population-based approaches often achieve larger reductions in health outcomes (e.g., seat-belt laws,52,53 alcohol and cigarette taxes,54–56 vaccine mandates) but often do so at a cost, in that not everyone will benefit from population approaches, and some may even be harmed. Population-based approaches to firearms control include potential policies such as ammunition taxes, gun-free zones, and product-safety engineering, and pursuit of population-based approaches are important adjuncts to reducing firearm violence.

We observed substantial decreases in rates of firearm-related suicide among those who were disqualified from gun ownership under all of our simulated scenarios. However, our agent-based model is calibrated on the basis of available data, which does not reflect all of those who are disqualified from gun ownership. Indeed, OMH data capture only a portion of those who are hospitalized because of psychiatric symptoms, and, furthermore, our model does not capture all those who are disqualified from gun ownership based on mental illness as historical commitment records may still prevent gun purchases during a background check.

New York City is also a geographic area with particularly low suicide rates—only about half the rate for the United States overall in 2002—and with a much smaller proportion of suicides caused by firearms (31% vs 54%).1 Furthermore, legislative efforts such as the Secure Ammunition and Firearms Enforcement Act in New York that expand the ability of the state to restrict firearm access to those with psychiatric disorders could influence firearm ownership and subsequently rates of firearm suicides in New York City in ways that would not be generalizable to other areas.

Despite these limitations, 2 results from our model do have broad generalizability. First, our results demonstrate that among the small group of individuals that we could calibrate to be disqualified from gun purchase, the reduction in firearm-related suicides associated with firearm denial is very high. To the extent that cities have higher rates of gun ownership and carrying, we would expect greater numbers of deaths to be prevented among all groups with greater restrictions on gun ownership.

Second, the group of individuals at high risk for psychiatric hospitalization is likely to be small in any jurisdiction, indicating that there will be small effects of disqualification on population rates of suicide regardless of prevalence of gun ownership, carrying, or suicide. Across all jurisdictions, our results indicate that disqualifications would need to be broadly defined to have a population impact. Overall, however, were we to apply these results to other calibrations of high-risk individuals in other states, the effects on population rates could be greater as gun access and ownership increase.57

Ownership disqualifications based on other risk factors beyond mental health should also be considered. Gun violence restraining orders, also known as extreme risk protection orders, are a promising approach to firearm violence prevention when individuals pose an imminent risk of harm to themselves or others—whether or not mental illness is involved.58–60 In general, they allow courts to mandate temporary recovery of firearms under such circumstances, following specified procedures and rules of evidence. Formal evaluations60 and anecdotal reports suggest they may be effective across a wide range of circumstances.61,62 Gun ownership restrictions based on timely behavioral indicators of risk, rather than records of psychiatric treatment, are likely to be both more effective and fair, although unintended consequences and equity should be considered for any ownership disqualification.

Several other considerations in the modeling framework affect interpretation of these results. As in all simulations, our results are dependent on a series of modeling assumptions and on the quality of the parameters that we used from existing data. Data on gun ownership and carrying are not routinely collected, and we relied on select sources of survey data to calibrate these aspects of our model. Firearm purchases through illicit marketplaces are common. We calibrated the illicit firearm marketplace in our model by allowing agents to carry firearms without purchase; as data become more available on the dynamics of firearm marketplaces, the development and calibration of agent-based and other simulation models to understand firearm injury dynamics will improve. Furthermore, we focused on specific model dynamics around social networks that facilitate firearm use but did not focus on social network factors that may be protective, such as social support; further extensions of simulation work that include a specific focus on the role of social networks are warranted.

The limitations of gun ownership and carrying data are balanced by our rigorous and robust data on prediction equations for mental illness, treatment, and outcome estimates of suicide. The quality of our data for these parameters underscores the utility of routinely collected high-quality surveillance and survey data that can be used for multiple public health goals, including simulation of anticipated policy and intervention benefits. We drew data from a variety of sources—based in New York City to the extent possible—but to the extent that parameters were not available, we relied on national sources and assumed that the strength of associations would be similar in New York City. However, we conducted extensive calibration and sensitivity analyses of key parameters and assumptions, mitigating concerns about the dependence of the model results on assumptions.

The study suggests that while high-risk approaches such as firearms denial criteria based on OMH-identified psychiatric hospitalization are effective for preventing suicide for those at high risk, broader approaches may be necessary to reduce firearm deaths at the population level, carefully calibrated to mitigate unintended consequences for stigma and help seeking. Our models estimated that denying firearm rights of the much larger population with any mental health treatment would significantly reduce the gun suicide rate at the population level, but at the cost of stigmatizing and needlessly restricting the rights of millions of people at low risk. Designing laws and policies to restrict firearms from those who pose a substantial risk, without abridging the rights of too many people who do not, remains a difficult challenge for suicide prevention.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Support for this work was provided by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (R21 DA041154, Keyes and Cerdá).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

This project was declared exempt by the Columbia University institutional review board because the analyses were based on de-identified data, and the agent-based model does not include human participants.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. WISQARS, fatal injury reports, national, regional and state, 1981–2016. 2017. Available at: https://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/mortrate.html. Accessed March 20, 2019.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Injury mortality in the United States, 1999–2016. 2017. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data-visualization/injury-mortality. Accessed March 20, 2019.

- 3.Fowler KA, Dahlberg LL, Haileyesus T, Annest JL. Firearm injuries in the United States. Prev Med. 2015;79:5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Office of Statistics and Programming, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. WISQARS. 10 leading causes of death by age group, United States—2010. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/pdf/10lcid_all_deaths_by_age_group_2010-a.pdf. Accessed March 20, 2019.

- 5.Cavanagh JTO, Carson AJ, Sharpe M, Lawrie SM. Psychological autopsy studies of suicide: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2003;33(3):395–405. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Z, Page A, Martin G, Taylor R. Attributable risk of psychiatric and socio-economic factors for suicide from individual-level, population-based studies: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(4):608–616. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shenassa ED, Catlin SN, Buka SL. Lethality of firearms relative to other suicide methods: a population based study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(2):120–124. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.2.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spicer RS, Miller TR. Suicide acts in 8 states: incidence and case fatality rates by demographics and method. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(12):1885–1891. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.12.1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zalsman G, Hawton K, Wasserman D et al. Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-year systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(7):646–659. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30030-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewiecki EM, Miller SA. Suicide, guns, and public policy. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(1):27–31. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swanson JW, Easter MM, Robertson AG et al. Gun violence, mental illness, and laws that prohibit gun possession: evidence from two Florida counties. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(6):1067–1075. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swanson JW, McGinty EE, Fazel S, Mays VM. Mental illness and reduction of gun violence and suicide: bringing epidemiologic research to policy. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(5):366–376. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGinty EE, Frattaroli S, Appelbaum PS et al. Using research evidence to reframe the policy debate around mental illness and guns: process and recommendations. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):e22–e26. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rose V. Mental illness and firearm law. Hartford, CT: Office of Legislative Research, Connecticut General Assembly; 2013.

- 15.Mueller B. Limiting access to guns for mentally ill is complicated. New York Times. February 15, 2018. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/15/us/gun-access-mentally-ill.html. Accessed March 20, 2019.

- 16.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2017. Available at: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FFR1-2016/NSDUH-FFR1-2016.pdf. Accessed March 20, 2019.

- 17.Link BG, Phelan JC, Bresnahan M, Stueve A, Pescosolido BA. Public conceptions of mental illness: labels, causes, dangerousness, and social distance. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1328–1333. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Metzl JM, MacLeish KT. Mental illness, mass shootings, and the politics of American firearms. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):240–249. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cerdá M, Tracy M, Keyes KM, Galea S. To treat or to prevent? Reducing the population burden of violence-related post-traumatic stress disorder. Epidemiology. 2015;26(5):681–689. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cerdá M, Tracy M, Keyes KM. Reducing urban violence: a contrast of public health and criminal justice approaches. Epidemiology. 2018;29(1):142–150. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keyes KM, Shev A, Tracy M, Cerda M. Assessing the impact of alcohol taxation on rates of violent victimization in a large urban area: an agent-based modeling approach. Addiction. 2018 doi: 10.1111/add.14470. epub ahead of print October 12, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cerdá M, Tracy M, Ahern J, Galea S. Addressing population health and health inequalities: the role of fundamental causes. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(suppl 4):S609–S619. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grimm V, Berger U, Bastiansen F et al. A standard protocol for describing individual-based and agent-based models. Ecol Modell. 2006;198(1-2):115–126. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grimm V, Berger U, DeAngelis DL, Polhill JG, Giske J, Railsback SF. The ODD protocol: a review and first update. Ecol Modell. 2010;221(23):2760–2768. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Summary files 1, 3, and 4. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2000.

- 26. 2017 NICS operations report. Washington, DC: Department of Justice; 2018.

- 27. Bureau of Vital Statistics, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Summary of vital statistics 2000. New York, NY: The City of New York; 2000.

- 28.Goldmann E, Aiello A, Uddin M et al. Pervasive exposure to violence and posttraumatic stress disorder in a predominantly African American Urban Community: the Detroit neighborhood health study. J Trauma Stress. 2011;24(6):747–751. doi: 10.1002/jts.20705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharkey P. Stuck in Place: Urban Neighborhoods and the End of Progress Toward Racial Equality. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kessler RC, Merikangas KR. The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(2):60–68. doi: 10.1002/mpr.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Guidelines for completing the 2013 Patient Characteristics Survey. Albany, NY: New York State Office of Mental Health; 2013.

- 32. Patient Characteristics Survey. Albany, NY: New York State Office of Mental Health; 2013.

- 33.Messner SF, Galea S, Tardiff KJ et al. Policing, drugs, and the homicide decline in New York City in the 1990s. Criminology. 2007;45(2):385–414. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galea S, Ahern J, Tracy M et al. Longitudinal determinants of posttraumatic stress in a population-based cohort study. Epidemiology. 2008;19(1):47–54. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31815c1dbf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaplan MS, McFarland BH, Huguet N et al. Acute alcohol intoxication and suicide: a gender-stratified analysis of the National Violent Death Reporting System. Inj Prev. 2013;19(1):38–43. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2012-040317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simon TR, Swann AC, Powell KE, Potter LB, Kresnow M, O’Carroll PW. Characteristics of impulsive suicide attempts and attempters. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2001;32(suppl 1):49–59. doi: 10.1521/suli.32.1.5.49.24212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brent DA, Perper JA, Allman CJ, Moritz GM, Wartella ME, Zelenak JP. The presence and accessibility of firearms in the homes of adolescent suicides: a case–control study. JAMA. 1991;266(21):2989–2995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blanco C, Krueger RF, Hasin DS et al. Mapping common psychiatric disorders: structure and predictive validity in the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(2):199–208. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Latalova K, Kamaradova D, Prasko J. Violent victimization of adult patients with severe mental illness: a systematic review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:1925–1939. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S68321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olfson M, Wall M, Wang S et al. Short-term suicide risk after psychiatric hospital discharge. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(11):1119–1126. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marsden PV. Core discussion networks of Americans. Am Sociol Rev. 1987;52(1):122–131. [Google Scholar]

- 42.McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Brashears ME. Social isolation in America: changes in core discussion networks over two decades. Am Sociol Rev. 2006;71(3):353–375. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tracy M, Braga AA, Papachristos AV. The transmission of gun and other weapon-involved violence within social networks. Epidemiol Rev. 2016;38(1):70–86. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxv009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Windrum P, Fagiolo G, Moneta A. Empirical validation of agent based models: alternatives and prospects. J Artif Soc Soc Simul. 2007;10(2):8. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Consortium for Risk-Based Firearm Policy. Guns, public health and mental illness: an evidence-based approach for state policy. 2013. Available at: http://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-center-for-gun-policy-and-research/publications/GPHMI-State.pdf. Accessed March 20, 2019.

- 46.Rose G. Sick individuals and sick populations. Int J Epidemiol. 1985;14(1):32–38. doi: 10.1093/ije/14.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watters JK, Estilo MJ, Clark GL, Lorvick J. Syringe and needle exchange as HIV/AIDS prevention for injection drug users. JAMA. 1994;271(2):115–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Emberson J, Whincup P, Morris R, Walker M, Ebrahim S. Evaluating the impact of population and high-risk strategies for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2004;25(6):484–491. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McGuire TG, Miranda J. New evidence regarding racial and ethnic disparities in mental health: Policy implications. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(2):393–403. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mental health: culture, race, and ethnicity. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2001.

- 51.Swanson J, Swartz M, Van Dorn RA et al. Racial disparities in involuntary outpatient commitment: are they real? Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(3):816–826. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chorba TL, Reinfurt D, Hulka BS. Efficacy of mandatory seat-belt use legislation: the North Carolina experience from 1983 through 1987. JAMA. 1988;260(24):3593–3597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Høye A. How would increasing seat belt use affect the number of killed or seriously injured light vehicle occupants? Accid Anal Prev. 2016;88:175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2015.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wagenaar AC, Salois MJ, Komro KA. Effects of beverage alcohol price and tax levels on drinking: a meta-analysis of 1003 estimates from 112 studies. Addiction. 2009;104(2):179–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ranson MK, Jha P, Chaloupka FJ, Nguyen SN. Global and regional estimates of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of price increases and other tobacco control policies Nicotine. Tob Res. 2002;4(3):311–319. doi: 10.1080/14622200210141000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chaloupka FJ, Tauras JA. The power of tax and price. Tob Control. 2011;20(6):391–392. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Swanson JW, Bonnie RJ, Appelbaum PS. Getting serious about reducing suicide: more “how” and less “why. JAMA. 2015;314(21):2229–2230. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Frattaroli S, Mcginty EE, Barnhorst A, Greenberg S. Gun violence restraining orders: alternative or adjunct to mental health–based restrictions on firearms? Behav Sci Law. 2015;33(2-3):290–307. doi: 10.1002/bsl.2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roskam K, Chaplin V. The gun violence restraining order: an opportunity for common ground in the gun violence debate. Dev Ment Health Law. 2017;36(2):1–51. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Swanson JW, Norko MA, Lin H et al. Implementation and effectiveness of Connecticut’s risk-based gun removal law: does it prevent suicides? Law Contemp Probl. 2017;80(2):179–208. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nolan C. City Attorney’s Office, San Diego Police working to protect the public from gun violence. Available at: https://www.sandiego.gov/sites/default/files/nr180216a.pdf. Accessed March 20, 2019.

- 62. Case series: Santa Barbara sheriff’s gun violence restraining order. Santa Barbara County, CA: Office of the Sheriff Santa Barbara County; 2016.